Global Patterns and Temporal Trends in Ovarian and Uterine Cancer Mortality Attributable to High Body-Mass Index, 1990–2023

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Variables and Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

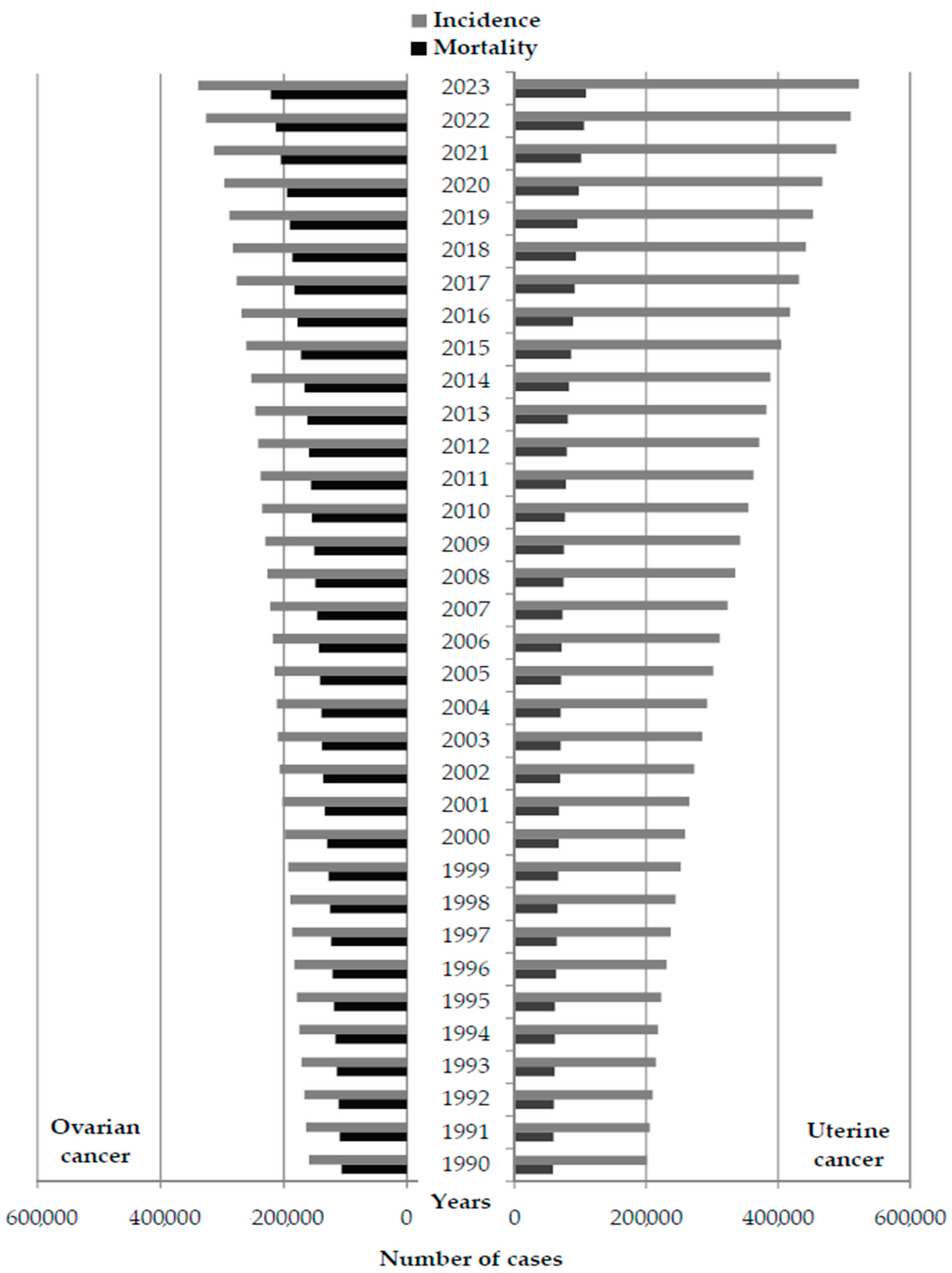

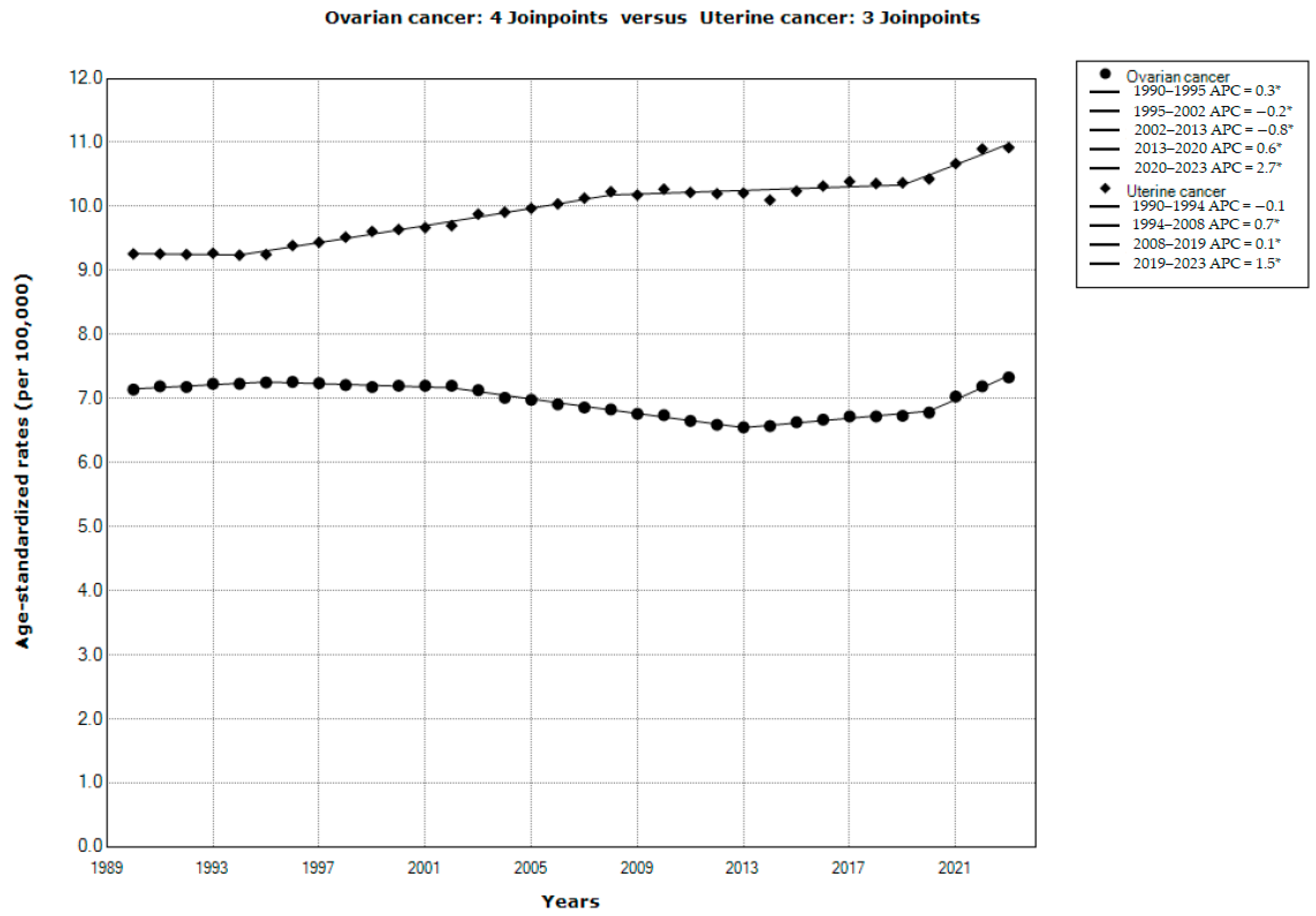

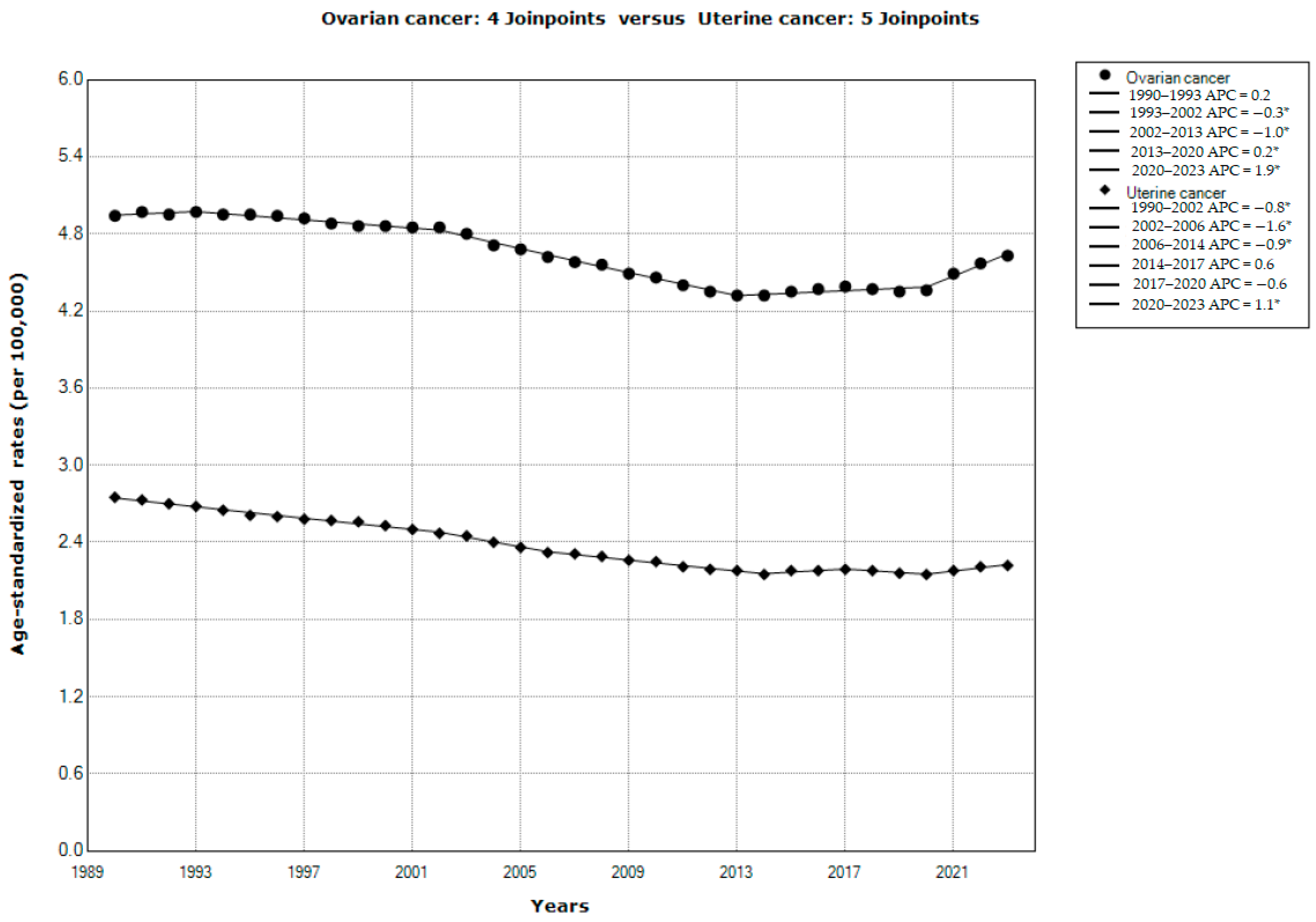

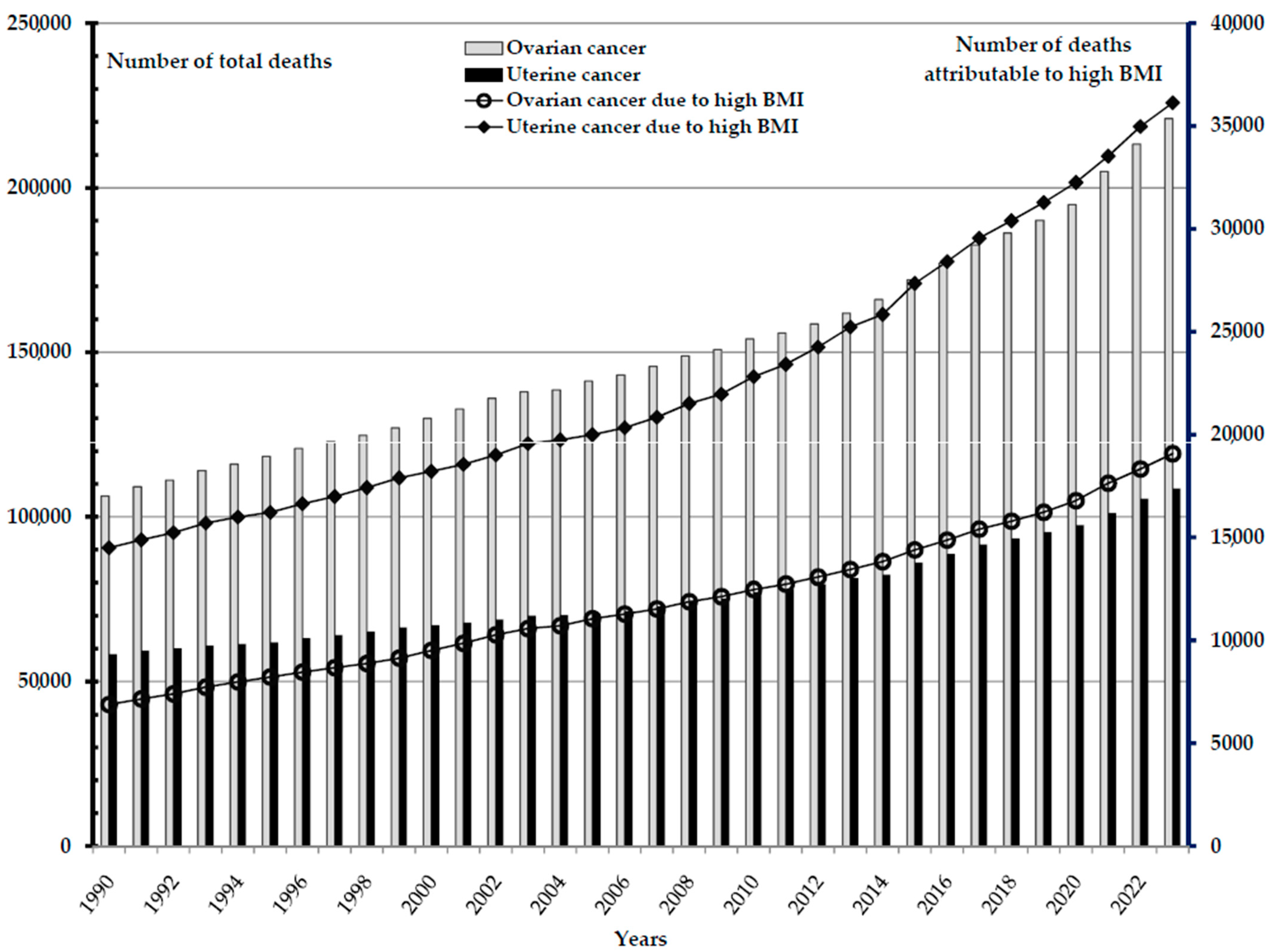

3. Results

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations of the Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferlay, J.; Ervik, M.; Lam, F.; Laversanne, M.; Colombet, M.; Mery, L.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2024; Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/today (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, Z.; Vali, M.; Nikbakht, H.A.; Hassanipour, S.; Kouhi, A.; Sedighi, S.; Farokhi, R.; Ghaem, H. Survival rate of ovarian cancer in Asian countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano Dos Santos, F.L.; Wojciechowska, U.; Michalek, I.M.; Didkowska, J. Survival of patients with cancers of the female genital organs in Poland, 2000–2019. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momenimovahed, Z.; Tiznobaik, A.; Taheri, S.; Salehiniya, H. Ovarian cancer in the world: Epidemiology and risk factors. Int. J. Womens Health 2019, 11, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsopoulos, J.; Gronwald, J.; Karlan, B.; Rosen, B.; Huzarski, T.; Moller, P.; Lynch, H.T.; Singer, C.F.; Senter, L.; Neuhausen, S.L.; et al. Age-specific ovarian cancer risks among women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 150, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Habeshian, T.S.; Zhang, J.; Peeri, N.C.; Du, M.; De Vivo, I.; Setiawan, V.W. Differential trends in rising endometrial cancer incidence by age, race, and ethnicity. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2023, 7, pkad001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Dai, X.; Chen, J.; Zeng, X.; Qing, X.; Huang, J.; Ren, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; Ruan, X. Global burden and trends in pre- and post-menopausal gynecological cancer from 1990 to 2019, with projections to 2040: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Surg. 2025, 111, 891–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, V.E.; Tanjasiri, S.P.; Ro, A.; Hoyt, M.A.; Bristow, R.E.; LeBrón, A.M.W. Trends in endometrial cancer incidence in the United States by race/ethnicity and age of onset from 2000 to 2019. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2025, 194, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, 21 October 2015, A/RES/70/1. Available online: http://www.refworld.org/docid/57b6e3e44.html (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Komatsu, H.; Ikeda, Y.; Kawana, K.; Nagase, S.; Yoshino, K.; Yamagami, W.; Tokunaga, H.; Kato, K.; Kimura, T.; Aoki, D.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 on gynecological cancer incidence: A large cohort study in Japan. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 29, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, A.; Nomura, H.; Abe, A.; Fusegi, A.; Aoki, Y.; Omi, M.; Tanigawa, T.; Okamoto, S.; Yunokawa, M.; Kanao, H. Influence of COVID-19 on the clinical characteristics of patients with uterine cervical cancer in Japan: A single-center retrospective study. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2024, 50, 2280–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Y.; Luo, P. Mortality of Three Major Gynecological Cancers in the European Region: An Age-Period-Cohort Analysis from 1992 to 2021 and Predictions in a 25-Year Period. Ann. Glob. Health 2025, 91, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adisu, M.A.; Habtie, T.E.; Kitaw, T.A.; Gessesse, A.D.; Woreta, B.M.; Derso, Y.A.; Zemariam, A.B. The rising burden of female cancer in Ethiopia (2000–2021) and projections to 2040: Insights from the global burden of disease study. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0333787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanha, K.; Mottaghi, A.; Nojomi, M.; Moradi, M.; Rajabzadeh, R.; Lotfi, S.; Janani, L. Investigation on factors associated with ovarian cancer: An umbrella review of systematic review and meta-analyses. J. Ovarian Res. 2021, 14, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jara-Rosales, S.; González-Stegmaier, R.; Rotarou, E.S.; Villarroel-Espíndola, F. Risk Factors for Ovarian Cancer in South America: A Literature Review. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Chan, W.C.; Ngai, C.H.; Lok, V.; Zhang, L.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E., 3rd; Xu, W.; Zheng, Z.J.; Elcarte, E.; Withers, M.; et al. Global incidence and mortality trends of corpus uteri cancer and associations with gross domestic product, human development index, lifestyle, and metabolic risk factors. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2023, 162, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bafligil, C.; Thompson, D.J.; Lophatananon, A.; Smith, M.J.; Ryan, N.A.; Naqvi, A.; Evans, D.G.; Crosbie, E.J. Association between genetic polymorphisms and endometrial cancer risk: A systematic review. J. Med. Genet. 2020, 57, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.T.; Al-Ani, O.; Al-Ani, F. Epidemiology and risk factors for ovarian cancer. Prz. Menopauzalny 2023, 22, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskas, M.; Crosbie, E.J.; Fokdal, L.; McCluggage, W.G.; Mileshkin, L.; Mutch, D.G.; Amant, F. Cancer of the corpus uteri: A 2025 update. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2025, 171, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Dai, H.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, P.; Song, F.; Zhang, B.; Chen, K. Age at menarche and epithelial ovarian cancer risk: A meta-analysis and Mendelian randomization study. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 4012–4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandera, E.V.; Qin, B.; Moorman, P.G.; Alberg, A.J.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S.; Bondy, M.; Cote, M.L.; Funkhouser, E.; Peters, E.S.; Schwartz, A.G.; et al. Obesity, weight gain, and ovarian cancer risk in African American women. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 139, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochs-Balcom, H.M.; Johnson, C.; Guertin, K.A.; Qin, B.; Beeghly-Fadiel, A.; Camacho, F.; Bethea, T.N.; Dempsey, L.F.; Rosenow, W.; Joslin, C.E.; et al. Racial differences in the association of body mass index and ovarian cancer risk in the OCWAA Consortium. Br. J. Cancer 2022, 127, 1983–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, A.; Esserman, D.A.; Cartmel, B.; Irwin, M.L.; Ferrucci, L.M. Association between diet quality and ovarian cancer risk and survival. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2024, 116, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, C.P.; Hong, H.G.; Abar, L.; Khandpur, N.; Steele, E.M.; Liao, L.M.; Sinha, R.; Trabert, B.; Loftfield, E. Ultraprocessed food intake and risk of ovarian and endometrial cancer in the NIH-AARP cohort: A prospective cohort analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 122, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Oh, H.; Song, Y.S.; Lee, Y.J.; Han, K.; Lee, M.K. Impact of Changes in Obesity and Abdominal Obesity on Endometrial Cancer Risk in Young Korean Women: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2025, 34, 1794–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aune, D.; Navarro Rosenblatt, D.A.; Chan, D.S.; Vingeliene, S.; Abar, L.; Vieira, A.R.; Greenwood, D.C.; Bandera, E.V.; Norat, T. Anthropometric factors and endometrial cancer risk: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 1635–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jia, X.; Zhou, R.; Wang, J. Association Between Abdominal Adipose Tissue Distribution and Risk of Endometrial Cancer: A Case-Control Study. Clin. Med. Insights Oncol. 2022, 16, 11795549221140776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). GBD Results; IHME, University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 2025; Available online: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/ (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Stevens, G.A.; Alkema, L.; Black, R.E.; Boerma, J.T.; Collins, G.S.; Ezzati, M.; Grove, J.T.; Hogan, D.R.; Hogan, M.C.; Horton, R.; et al. Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting: The GATHER statement. Lancet 2016, 388, e19–e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Burden of Disease 2019 Cancer Collaboration; Kocarnik, J.M.; Compton, K.; Dean, F.E.; Fu, W.; Gaw, B.L.; Harvey, J.D.; Henrikson, H.J.; Lu, D.; Pennini, A.; et al. Cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life years for 29 cancer groups from 2010 to 2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 420–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Disease and Related Health Problems: 10th Revision [Internet]; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Disease: 9th Revision [Internet]; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/classification-of-diseases (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- United Nations (UN). National Accounts Main Aggregates Database. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/snaama (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- GBD 2019 Demographics Collaborators. Global age-sex-specific fertility, mortality, healthy life expectancy (HALE), and population estimates in 204 countries and territories, 1950–2019: A comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1160–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden and strength of evidence for 88 risk factors in 204 countries and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2162–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Fay, M.P.; Feuer, E.J.; Midthune, D.N. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat. Med. 2000, 19, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, P.M. Fitting segmented regression models by grid search. Appl. Stat. 1980, 29, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, L.X.; Hankey, B.F.; Tiwari, R.; Feuer, E.J.; Edwards, B.K. Estimating average annual per cent change in trend analysis. Stat. Med. 2009, 28, 3670–3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Fay, M.P.; Yu, B.; Barrett, M.J.; Feuer, E.J. Comparability of segmented line regression models. Biometrics 2004, 60, 1005–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.Y.; Zheng, L.; Xiong, M.; Wang, S.L.; Jin, Q.Q.; Yang, Y.T.; Fang, Y.X.; Hong, L.; Mei, J.; Zhou, S.G. Body Mass Index and Risk of Female Reproductive System Tumors Subtypes: A Meta-Analysis Using Mendelian Randomization. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2024, 23, 15330338241277699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhao, J.; Du, P.; Fan, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Fan, Y. Global burden and trends in ovarian cancer attributable to environmental risks and occupational risks in females aged 20–49 from 1990 to 2021, with projections to 2050: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.S.; Kim, S.I.; Han, Y.; Yoo, J.; Seol, A.; Jo, H.; Lee, J.; Wang, W.; Han, K.; Song, Y.S. Risk of female-specific cancers according to obesity and menopausal status in 2•7 million Korean women: Similar trends between Korean and Western women. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2021, 11, 100146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.S.; Yoon, C.; Myung, S.K.; Park, S.M. Effect of obesity on survival of women with epithelial ovarian cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2011, 21, 1525–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandera, E.V.; Lee, V.S.; Qin, B.; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, L.; Powell, C.B.; Kushi, L.H. Impact of body mass index on ovarian cancer survival varies by stage. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 117, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, G.; Brezinov, Y.; Tzur, Y.; Bar-Noy, T.; Brodeur, M.N.; Salvador, S.; Lau, S.; Gotlieb, W. Association between BMI and oncologic outcomes in epithelial ovarian cancer: A predictors-matched case-control study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 310, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsopoulos, J.; Moody, J.R.; Fan, I.; Rosen, B.; Risch, H.A.; McLaughlin, J.R.; Sun, P.; Narod, S.A. Height, weight, BMI and ovarian cancer survival. Gynecol. Oncol. 2012, 127, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moysich, K.B.; Baker, J.A.; Menezes, R.J.; Jayaprakash, V.; Rodabaugh, K.J.; Odunsi, K.; Beehler, G.P.; McCann, S.E.; Villella, J.A. Usual adult body mass index is not predictive of ovarian cancer survival. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2007, 16, 626–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secord, A.A.; Hasselblad, V.; Von Gruenigen, V.E.; Gehrig, P.A.; Modesitt, S.C.; Bae-Jump, V.; Havrilesky, L.J. Body mass index and mortality in endometrial cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 140, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokts-Porietis, R.L.; Elmrayed, S.; Brenner, D.R.; Friedenreich, C.M. Obesity and mortality among endometrial cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrelli, F.; Cortellini, A.; Indini, A.; Tomasello, G.; Ghidini, M.; Nigro, O.; Salati, M.; Dottorini, L.; Iaculli, A.; Varricchio, A.; et al. Association of Obesity With Survival Outcomes in Patients With Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e213520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagle, C.M.; Dixon, S.C.; Jensen, A.; Kjaer, S.K.; Modugno, F.; de Fazio, A.; Fereday, S.; Hung, J.; Johnatty, S.E.; Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group; et al. Obesity and survival among women with ovarian cancer: Results from the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 113, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matz, M.; Coleman, M.P.; Sant, M.; Chirlaque, M.D.; Visser, O.; Gore, M.; Allemani, C.; The CONCORD Working Group. The histology of ovarian cancer: Worldwide distribution and implications for international survival comparisons (CONCORD-2). Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 144, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Bi, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zheng, Z.J. Global Incidence of Ovarian Cancer According to Histologic Subtype: A Population-Based Cancer Registry Study. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2024, 10, e2300393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann, K.; Cvancarova, M.; Eskild, A. Body mass index, diabetes and survival after diagnosis of endometrial cancer: A report from the HUNT-Survey. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 139, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, A.B.; Hare-Bruun, H.; Høgdall, C.K.; Rudnicki, M. Influence of Body Mass Index on Tumor Pathology and Survival in Uterine Cancer: A Danish Register Study. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2017, 27, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beavis, A.L.; Smith, A.J.; Fader, A.N. Lifestyle changes and the risk of developing endometrial and ovarian cancers: Opportunities for prevention and management. Int. J. Womens Health 2016, 8, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vali, M.; Maleki, Z.; Jahani, M.A.; Nazemi, S.; Ghelichi-Ghojogh, M.; Hassanipour, S.; Javanian, M.; Nikbakht, H.A. A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of uterine cancer in Asian countries. Casp. J. Intern. Med. 2025, 16, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagi, A.; Ueda, Y.; Ikeda, S.; Miyoshi, A.; Nakagawa, S.; Hiramatsu, K.; Kobayashi, E.; Kimura, T.; Ito, Y.; Nakayama, T.; et al. Improved long-term survival of corpus cancer in Japan: A 40-year population-based analysis. Int. J. Cancer 2022, 150, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rath, S.; Khan, M.; Aziz, N.; Nabi, W.; Bhat, A. Assessing the contribution of metabolic risk factors to uterine cancer-related deaths and predictions until 2030 and 2050. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, e17642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Fertility and Forecasting Collaborators. Global fertility in 204 countries and territories, 1950–2021, with forecasts to 2100: A comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2057–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lortet-Tieulent, J.; Ferlay, J.; Bray, F.; Jemal, A. International Patterns and Trends in Endometrial Cancer Incidence, 1978–2013. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modesitt, S.C.; Tian, C.; Kryscio, R.; Thigpen, J.T.; Randall, M.E.; Gallion, H.H.; Fleming, G.F.; Gynecologic Oncology Group. Impact of body mass index on treatment outcomes in endometrial cancer patients receiving doxorubicin and cisplatin: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2007, 105, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, J.T.; Barton, G.; Riedley-Malone, S.; Wan, J.Y. Obesity and perioperative outcomes in endometrial cancer surgery. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2012, 285, 1139–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, N.; Wu, Y.; Li, B.; Chen, W. Burden of female breast and five gynecological cancers in China and worldwide. Chin. Med. J. 2024, 137, 2190–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouzoulas, D.; Karalis, T.; Sofianou, I.; Anthoulakis, C.; Tzika, K.; Zafrakas, M.; Timotheadou, E.; Grimbizis, G.; Tsolakidis, D. The Impact of Treatment Delay on Endometrial and Ovarian Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2025, 17, 2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, H.S.; Kim, H.J.; Hong, J.H.; Lee, J.K.; Lee, N.W.; Song, J.Y. Obesity and epithelial ovarian cancer survival: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Ovarian Res. 2014, 7, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chlebowski, R.; LaMonte, M.J.; Bea, J.W.; Qi, L.; Wallace, R.; Lavasani, S.; Walsh, B.W.; Anderson, G.; Vitolins, M.; et al. Body mass index, physical activity, and mortality in women diagnosed with ovarian cancer: Results from the Women’s Health Initiative. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 133, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arem, H.; Chlebowski, R.; Stefanick, M.L.; Anderson, G.; Wactawski-Wende, J.; Sims, S.; Gunter, M.J.; Irwin, M.L. Body mass index, physical activity, and survival after endometrial cancer diagnosis: Results from the Women’s Health Initiative. Gynecol. Oncol. 2013, 128, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arem, H.; Park, Y.; Pelser, C.; Ballard-Barbash, R.; Irwin, M.L.; Hollenbeck, A.; Gierach, G.L.; Brinton, L.A.; Pfeiffer, R.M.; Matthews, C.E. Prediagnosis body mass index, physical activity, and mortality in endometrial cancer patients. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013, 105, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, V.M.; Newcomb, P.A.; Trentham-Dietz, A.; Hampton, J.M. Obesity, diabetes, and other factors in relation to survival after endometrial cancer diagnosis. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2007, 17, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cespedes Feliciano, E.M.; Prentice, R.L.; Aragaki, A.K.; Neuhouser, M.L.; Banack, H.R.; Kroenke, C.H.; Ho, G.Y.F.; Zaslavsky, O.; Strickler, H.D.; Cheng, T.D.; et al. Methodological considerations for disentangling a risk factor’s influence on disease incidence versus postdiagnosis survival: The example of obesity and breast and colorectal cancer mortality in the Women’s Health Initiative. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 2281–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, J.; Hilliard, T.S.; Wang, Z.; Johnson, J.; Wang, W.; Harper, E.I.; Ott, C.; O’Brien, C.; Campbell, L.; et al. Host obesity alters the ovarian tumor immune microenvironment and impacts response to standard of care chemotherapy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 42, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pati, S.; Irfan, W.; Jameel, A.; Ahmed, S.; Shahid, R.K. Obesity and Cancer: A Current Overview of Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Outcomes, and Management. Cancers 2023, 15, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avgerinos, K.I.; Spyrou, N.; Mantzoros, C.S.; Dalamaga, M. Obesity and cancer risk: Emerging biological mechanisms and perspectives. Metabolism 2019, 92, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: A pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2024, 403, 1027–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.; Wang, L.; Lou, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Yu, S.; Xuan, F. Temporal trends in cancer mortality attributable to high BMI in Asia: An age-period-cohort analysis based on GBD 1992–2021. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1691487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tham, K.W.; Abdul Ghani, R.; Cua, S.C.; Deerochanawong, C.; Fojas, M.; Hocking, S.; Lee, J.; Nam, T.Q.; Pathan, F.; Saboo, B.; et al. Obesity in South and Southeast Asia-A new consensus on care and management. Obes. Rev. 2023, 24, e13520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Xu, S.; Yang, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H.; Cheng, Y.; Zou, Y.; Ye, H.; Wang, P. Epidemiological trends of gynecologic cancer burden in east Asian countries from 1990 to 2021 and projections to 2031. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2026, 172, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, S.; Parveen, R. Scenario of endometrial cancer in Asian countries:epidemiology, risk factors and challenges. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2025, 12, 2921–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser-Weippl, K.; Chavarri-Guerra, Y.; Villarreal-Garza, C.; Bychkovsky, B.L.; Debiasi, M.; Liedke, P.E.; Soto-Perez-de-Celis, E.; Dizon, D.; Cazap, E.; de Lima Lopes, G., Jr.; et al. Progress and remaining challenges for cancer control in Latin America and the Caribbean. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 1405–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Star, J.; Bandi, P.; Siegel, R.L.; Han, X.; Minihan, A.; Smith, R.A.; Jemal, A. Cancer Screening in the United States During the Second Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 4352–4359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVIDSurg Collaborative. Effect of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns on planned cancer surgery for 15 tumour types in 61 countries: An international, prospective, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 1507–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elit, L.M.; O’Leary, E.M.; Pond, G.R.; Seow, H.Y. Impact of wait times on survival for women with uterine cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohl, A.E.; Feinglass, J.M.; Shahabi, S.; Simon, M.A. Surgical wait time: A new health indicator in women with endometrial cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 141, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, H. Impact of Treatment Delay on the Prognosis of Patients with Ovarian Cancer: A Population-based Study Using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Database. J. Cancer 2024, 15, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVIDSurg Collaborative; GlobalSurg Collaborative. Timing of surgery following SARS-CoV-2 infection: An international prospective cohort study. Anaesthesia 2021, 76, 748–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staley, S.A.; Tucker, K.R.; Clark, L.H. The Role of Obesity in the Development and Management of Gynecologic Cancer. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2020, 75, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, L.A.; Trabert, B.; DeSantis, C.E.; Miller, K.D.; Samimi, G.; Runowicz, C.D.; Gaudet, M.M.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Ovarian cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, T.; Mullangi, S.; Vadakekut, E.S.; Lekkala, M.R. Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. 2024 May 6. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Suratkal, J.; D’Silva, T.; AlHilli, M. The role of diet, obesity and body composition in epithelial ovarian cancer development and progression: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2025, 58, 101718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paschou, S.A.; Andrikopoulou, A.; Mili, N.; Svarna, A.; Kaparelou, M.; Stefanaki, K.; Dedes, N.; Liatsou, E.; Thomakos, N.; Haidopoulos, D.; et al. Possible Prognostic Role of BMI Before Chemotherapy in the Outcomes of Women with Ovarian Cancer. Nutrients 2025, 17, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichmann, I.A.; Cuello, M.A. Obesity and gynecological cancers: A toxic relationship. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2021, 155, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavone, M.; Goglia, M.; Taliento, C.; Lecointre, L.; Bizzarri, N.; Fanfani, F.; Fagotti, A.; Scambia, G.; Marescaux, J.; Querleu, D.; et al. Obesity paradox: Is a high body mass index positively influencing survival outcomes in gynecological cancers? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2024, 34, 1253–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ovarian Cancer | Uterine Cancer | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locations | Count in 2023 | ASR in 2023 | AAPC (ASR) (95% CI) | Count in 2023 | ASR in 2023 | AAPC (ASR) (95% CI) |

| Global | 19,069 | 0.40 | 0.4 * (0.3 to 0.5) | 36,136 | 0.74 | 0.1 * (0.0 to 0.2) |

| GBD regions | ||||||

| Andean Latin America | 209 | 0.61 | 4.2 * (3.6 to 4.8) | 456 | 1.33 | 0.0 (−0.3 to 0.3) |

| Australasia | 178 | 0.59 | −0.2 * (−0.4 to −0.1) | 311 | 1.00 | 0.9 * (0.7 to 1.1) |

| Caribbean | 139 | 0.47 | 2.2 * (2.1 to 2.4) | 553 | 1.85 | 1.9 * (1.7 to 2.1) |

| Central Asia | 251 | 0.48 | 1.1 * (0.9 to 1.3) | 539 | 1.05 | −0.6 * (−0.9 to −0.4) |

| Central Europe | 939 | 0.75 | 1.7 * (1.4 to 1.9) | 2023 | 1.50 | 0.6 * (0.4 to 0.7) |

| Central Latin America | 993 | 0.67 | 2.3 * (2.1 to 2.4) | 1365 | 0.93 | 1.1 * (0.7 to 1.5) |

| Central Sub-Saharan Africa | 163 | 0.40 | 5.6 * (5.1 to 6.1) | 169 | 0.45 | 3.4 * (3.1 to 3.7) |

| East Asia | 1295 | 0.11 | 1.2 * (0.7 to 1.6) | 3115 | 0.26 | −2.2 * (−2.6 to −1.8) |

| Eastern Europe | 1613 | 0.76 | 0.3 * (0.1 to 0.5) | 4283 | 1.88 | 0.3 * (0.1 to 0.5) |

| Eastern Sub-Saharan Africa | 349 | 0.27 | 6.1 * (5.9 to 6.4) | 547 | 0.48 | 3.1 * (2.9 to 3.3) |

| High-income Asia Pacific | 316 | 0.15 | 0.9 * (0.7 to 1.1) | 985 | 0.43 | 1.0 * (0.7 to 1.2) |

| High-income North America | 2568 | 0.73 | −0.3 * (−0.6 to −0.0) | 6215 | 1.69 | 1.7 * (1.6 to 1.9) |

| North Africa and Middle East | 1585 | 0.62 | 2.3 * (2.2 to 2.4) | 1973 | 0.81 | 1.1 * (1.0 to 1.2) |

| Oceania | 9 | 0.19 | 2.5 * (2.3 to 2.7) | 62 | 1.43 | 1.4 * (1.3 to 1.5) |

| South Asia | 2455 | 0.29 | 8.7 * (8.1 to 9.2) | 2397 | 0.29 | 4.2 * (4.0 to 4.4) |

| Southeast Asia | 985 | 0.24 | 4.6 * (4.4 to 4.8) | 1976 | 0.49 | 2.8 * (2.7 to 2.8) |

| Southern Latin America | 373 | 0.74 | 1.0 * (0.9 to 1.1) | 541 | 1.01 | −0.4 * (−0.6 to −0.1) |

| Southern Sub-Saharan Africa | 264 | 0.65 | 2.2 * (1.9 to 2.5) | 374 | 0.96 | 1.7 * (1.4 to 2.0) |

| Tropical Latin America | 636 | 0.43 | 1.9 * (1.7 to 2.1) | 1484 | 0.99 | 0.6 * (0.5 to 0.7) |

| Western Europe | 3131 | 0.61 | −0.7 * (−0.8 to −0.6) | 5884 | 1.06 | 0.7 * (0.6 to 0.8) |

| Western Sub-Saharan Africa | 620 | 0.45 | 3.7 * (3.4 to 3.9) | 883 | 0.74 | 2.1 * (1.8 to 2.3) |

| Age (Years) ** | 1990 | 2023 | 1990–2023 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Rate (per 100,000) | Count | Rate (per 100,000) | AAPC (%) | 95% CI | |

| Ovarian cancer | ||||||

| 20–24 | 7 | 0.00 | 53 | 0.02 | 5.0 * | 4.7 to 5.3 |

| 25–29 | 24 | 0.01 | 130 | 0.04 | 4.0 * | 3.8 to 4.3 |

| 30–34 | 60 | 0.03 | 282 | 0.10 | 3.0 * | 2.7 to 3.4 |

| 35–39 | 115 | 0.07 | 449 | 0.16 | 2.3 * | 1.9 to 2.6 |

| 40–44 | 219 | 0.16 | 790 | 0.31 | 1.6 * | 1.3 to 2.0 |

| 45–49 | 360 | 0.32 | 1273 | 0.54 | 1.1 * | 0.9 to 1.3 |

| 50–54 | 670 | 0.64 | 1897 | 0.84 | 0.6 * | 0.5 to 0.7 |

| 55–59 | 830 | 0.90 | 2274 | 1.08 | 0.4 * | 0.3 to 0.5 |

| 60–64 | 1069 | 1.30 | 2587 | 1.48 | 0.3 * | 0.2 to 0.4 |

| 65–69 | 1104 | 1.66 | 2686 | 1.79 | 0.0 | 0.0 to 0.0 |

| 70–74 | 852 | 1.81 | 2377 | 2.00 | −0.1 | −0.2 to 0.1 |

| 75–79 | 808 | 2.21 | 1829 | 2.30 | −0.0 | −0.2 to 0.1 |

| 80–84 | 485 | 2.16 | 1308 | 2.45 | 0.2 | −0.0 to 0.4 |

| 85–89 | 214 | 2.06 | 738 | 2.34 | 0.2 | −0.0 to 0.5 |

| 90–94 | 61 | 1.93 | 313 | 2.36 | 0.7 * | 0.4 to 1.0 |

| 95+ | 9 | 1.09 | 81 | 1.82 | 1.6 * | 1.3 to 2.0 |

| Total/Age-standardized: | 6887 | 0.32 | 19,069 | 0.40 | 0.4 * | 0.3 to 0.5 |

| Uterine cancer | ||||||

| 20–24 | 25 | 0.01 | 33 | 0.01 | −0.1 | −0.5 to 0.3 |

| 25–29 | 60 | 0.03 | 106 | 0.04 | 0.2 | −0.2 to 0.5 |

| 30–34 | 130 | 0.07 | 246 | 0.08 | −0.2 | −0.5 to 0.1 |

| 35–39 | 239 | 0.14 | 430 | 0.15 | −0.3 | −0.5 to 0.0 |

| 40–44 | 341 | 0.24 | 771 | 0.30 | 0.1 | −0.1 to 0.4 |

| 45–49 | 536 | 0.47 | 1358 | 0.58 | 0.2 | −0.0 to 0.3 |

| 50–54 | 1019 | 0.97 | 2309 | 1.02 | 0.0 | −0.1 to 0.1 |

| 55–59 | 1446 | 1.57 | 3348 | 1.60 | −0.0 | −0.1 to 0.1 |

| 60–64 | 2274 | 2.77 | 5062 | 2.89 | 0.1 | −0.1 to 0.3 |

| 65–69 | 2485 | 3.74 | 5925 | 3.95 | 0.0 | −0.1 to 0.2 |

| 70–74 | 1998 | 4.25 | 5658 | 4.77 | 0.1 | −0.1 to 0.2 |

| 75–79 | 1898 | 5.19 | 4335 | 5.44 | 0.2 * | 0.0 to 0.3 |

| 80–84 | 1232 | 5.49 | 3238 | 6.06 | 0.2 * | 0.2 to 0.3 |

| 85–89 | 573 | 5.53 | 2018 | 6.41 | 0.4 * | 0.3 to 0.5 |

| 90–94 | 197 | 6.23 | 980 | 7.38 | 0.7 * | 0.6 to 0.8 |

| 95+ | 43 | 5.34 | 318 | 7.11 | 1.1 * | 1.0 to 1.2 |

| Total/Age-standardized: | 14,495 | 0.68 | 36,136 | 0.74 | 0.1 * | 0.0 to 0.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ilic, I.; Jakovljevic, V.; Lazic, S.; Ilic, M. Global Patterns and Temporal Trends in Ovarian and Uterine Cancer Mortality Attributable to High Body-Mass Index, 1990–2023. Cancers 2026, 18, 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010157

Ilic I, Jakovljevic V, Lazic S, Ilic M. Global Patterns and Temporal Trends in Ovarian and Uterine Cancer Mortality Attributable to High Body-Mass Index, 1990–2023. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):157. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010157

Chicago/Turabian StyleIlic, Irena, Vladimir Jakovljevic, Srdjan Lazic, and Milena Ilic. 2026. "Global Patterns and Temporal Trends in Ovarian and Uterine Cancer Mortality Attributable to High Body-Mass Index, 1990–2023" Cancers 18, no. 1: 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010157

APA StyleIlic, I., Jakovljevic, V., Lazic, S., & Ilic, M. (2026). Global Patterns and Temporal Trends in Ovarian and Uterine Cancer Mortality Attributable to High Body-Mass Index, 1990–2023. Cancers, 18(1), 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010157