Targeting the MAPK Pathway in Brain Tumors: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Central Nervous System (CNS) Tumors

2.1. MAPK Pathway Alterations in CNS Tumors

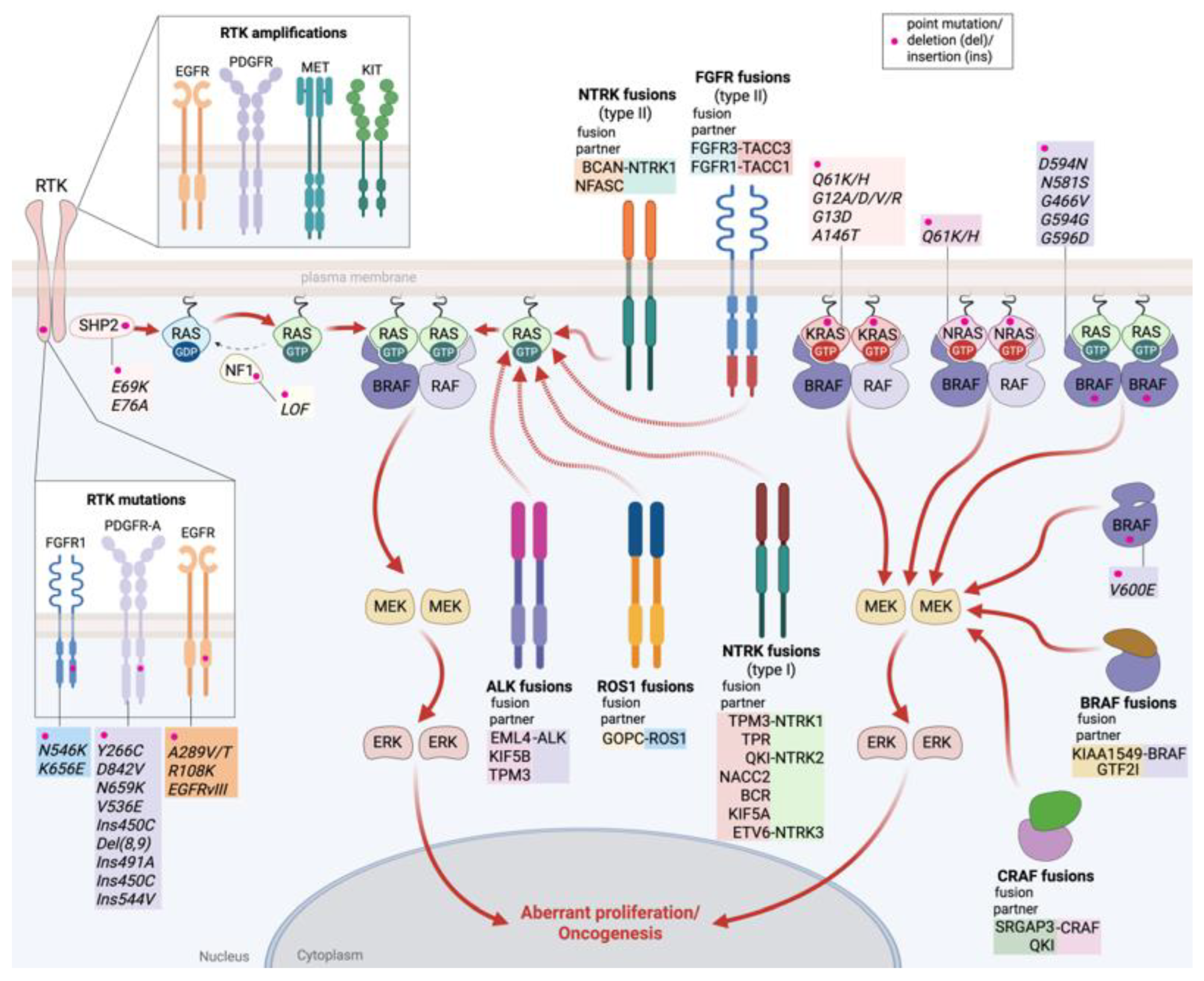

2.1.1. Receptor Tyrosine Kinase (RTK) Alterations

2.1.2. RAS Alterations

2.1.3. MAPK Pathway Regulators Alterations

2.1.4. RAF Alterations

3. RAS/MAPK Pathway Inhibitors in CNS Tumors

3.1. RAF Inhibitors

3.1.1. Vemurafenib

3.1.2. Dabrafenib

3.1.3. Encorafenib

3.1.4. NST-628

3.2. MEK Inhibitors

3.2.1. Selumetinib

3.2.2. Trametinib

3.2.3. Binimetinib and Cobimetinib

3.2.4. Mirdametinib

3.3. ERK Inhibitors

Ulixertinib (BVD-523)

3.4. SHP2 Protein Inhibitors

3.5. Combinatorial Therapies

3.6. Clinical Application and Efficacy

3.6.1. Pediatric Low-Grade Glioma (LGG)

3.6.2. High-Grade Glioma (HGG)

3.6.3. Ganglioglioma

3.6.4. Medulloblastoma

3.7. Current and Ongoing Clinical Trials

4. Therapeutic Challenges of Targeting the MAPK Pathway in Brain Tumors

4.1. Blood–Brain Barrier (BBB) and Drug Delivery Limitations

4.2. Tumor Heterogeneity and Resistance Mechanisms in MAPK Pathway-Targeted Therapies

4.3. Tumor Microenvironment (TME)

4.4. Toxicities Associated with MAPK Pathway Inhibitors

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2-HG | 2-hydroxyglutarate |

| ABC | ATP-binding cassette |

| AKT | protein kinase B (PKB) |

| ALK | anaplastic lymphoma kinase |

| ARAF | A-Raf proto-oncogene |

| ASIR | age-standardized incidence rate |

| ATRX | α-thalassemia intellectual disability X-linked |

| BBB | blood–brain barrier |

| BCAN | brevican |

| BCR | breakpoint cluster region |

| BCRP | breast cancer resistance protein |

| BRAF | v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B |

| BTB | blood–tumor barrier |

| CAR | glioblastoma multiforme |

| CDK4 | cyclin-dependent kinase 4 |

| CDKN2A/B | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A/2B |

| CLCN6 | CLCN6 chloride voltage-gated channel |

| CLIP2 | CAP-Gly domain containing linker protein 2 |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| CRAF | proto-oncogene c-Raf |

| DHGG | diffuse high-grade glioma |

| DIG | desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma |

| DLGG | diffuse low-grade glioma |

| EGFR | epidermal growth factor receptor |

| ERK | extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| ETV6 | Ets variant transcription factor 6 |

| FAM131B | family with sequence similarity 131 member B |

| FDA | food and drug administration |

| FGFR | fibroblast growth factor receptor |

| FZR1 | fizzy and cell division cycle 20 related 1 |

| GBD | global burden of disease |

| GBM | glioblastoma multiforme |

| GNA11 | guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit alpha 11 |

| GOPC | Golgi-associated PDZ and coiled-coil motif-containing protein |

| GTF2I | general transcription factor II-I |

| GTPase | guanosine triphosphatase |

| HGG | high-grade glioma |

| HQ | hydroxychloroquine |

| HRAS | Harvey rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog |

| ICI | immune checkpoint inhibitor |

| IDH | isocitrate dehydrogenase |

| IHG | infant-type hemispheric glioma |

| IL-13Rα2 | interleukine-13Rα2 |

| KLF4 | Krüppel-like factor 4 |

| KRAS | Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog |

| LGG | low-grade glioma |

| LZTR1 | leucine zipper-like transcription regulator 1 |

| MACF1 | microtubule actin crosslinking factor 1 |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MEK | mitogen-activated protein kinase extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| MET | met tyrosine-protein kinase |

| MKRN1 | makorin ring finger protein 1 |

| MPNST | malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor |

| MRP | multidrug resistance-associated protein |

| MYB | v-myb avian myeloblastosis viral oncogene homolog |

| NACC2 | nucleus Accumbens-associated protein 2 |

| NF1 | neurofibromin |

| NF1A | nuclear transcription factor 1A (NF1A) |

| NFASC | neurofascin |

| NOTCH | neurogenic locus notch homolog |

| NRAS | neuroblastoma rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog |

| NTRK | neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase |

| OLIG2 | oligodendrocyte transcription factor 2 |

| PA | pilocytic astrocytoma |

| PD-1 | programmed cell death-1 |

| PDGFR-A | platelet-derived growth factor receptor A |

| PD-L1 | programmed death-ligand 1 |

| PFS | progression-free survival |

| P-gp | p-glycoprotein |

| PI3K | phosphoinositide 3 kinase |

| PIK3CA | phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha |

| PN | plexiform neurofibroma |

| PRKAR2A | protein kinase cAMP-dependent type II regulatory subunit α |

| PROTAC | proteolysis-targeting chimera |

| PTPRZ1 | protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type Z1 |

| PXA | pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma |

| QKI | quaking homolog KH domain containing RNA binding |

| RAF | rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma |

| RAS | rat sarcoma virus oncogene |

| RB1 | retinoblastoma susceptibility gene |

| RNF130 | ring finger protein 130 |

| ROS1 | ROS proto-oncogene 1 |

| RTK | receptor tyrosine kinase |

| SASP | senescence-associated secretory phenotype |

| SHP2 | Src homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatase-2 |

| SOX2 | SRY-box transcription factor 2 |

| SPRED1 | sprouty-related EVH1 domain-containing protein 1 |

| SRGAP3 | rho GTPase activating protein 3 |

| STAT3 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| TACC3 | transforming acidic coiled-coil containing protein 3 |

| TERT | telomerase reverse transcriptase |

| TME | tumor microenvironment |

| TMZ | temozolomide |

| TPM3 | tropomyosin 3 |

| TrkB | tropomyosin receptor kinase B |

| WHO | world health organization |

References

- Kim, S.; Son, Y.; Oh, J.; Kim, S.; Jang, W.; Lee, S.; Smith, L.; Pizzol, D.; Lee, J.; Lee, H.; et al. Global burden of brain and central nervous system cancer in 185 countries, and projections up to 2050: A population-based systematic analysis of GLOBOCAN 2022. J. Neurooncol. 2025, 175, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Chan, S.C.; Lok, V.; Zhang, L.; Lin, X.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E.; Xu, W.; Zheng, Z.-J.; Elcarte, E.; Withers, M.; et al. Disease burden, risk factors, and trends of primary central nervous system (CNS) cancer: A global study of registries data. Neuro Oncol. 2023, 25, 995–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldape, K.; Brindle, K.M.; Chesler, L.; Chopra, R.; Gajjar, A.; Gilbert, M.R.; Gottardo, N.; Gutmann, D.H.; Hargrave, D.; Holland, E.C.; et al. Challenges to curing primary brain tumours. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 16, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; He, M.; Yang, R.; Geng, N.; Zhu, X.; Tang, N. The global, regional, and national brain and central nervous system cancer burden and trends from 1990 to 2021: An analysis based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1574614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angom, R.S.; Nakka, N.M.R.; Bhattacharya, S. Advances in glioblastoma therapy: An update on current approaches. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, M.D.; Beadling, C.; Neff, T.; Moore, S.; Harrington, C.A.; Baird, L.; Corless, C. Molecular profiling of pre- and post-treatment pediatric high-grade astrocytomas reveals acquired increased tumor mutation burden in a subset of recurrences. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2023, 11, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Xu, K.; Zhu, X.; Dunphy, P.S.; Gudenas, B.; Lin, W.; Twarog, N.; Hover, L.D.; Kwon, C.H.; Kasper, L.H.; et al. Patient-derived models recapitulate heterogeneity of molecular signatures and drug response in pediatric high-grade glioma. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, R.; Yin, Q.; Snell, A.H.; Wan, L.; 8. RAF-MEK-ERK pathway in cancer evolution and treatment. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 85, 123–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samatar, A.A.; Poulikakos, P.I. Targeting RAS-ERK signalling in cancer: Promises and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 928–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, B.; Skolnik, E.Y. Activation of Ras by receptor tyrosine kinases. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1994, 5, 1288–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marais, R.; Light, Y.; Paterson, H.F.; Marshall, C.J. Ras recruits Raf-1 to the plasma membrane for activation by tyrosine phosphorylation. EMBO J. 1995, 14, 3136–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crews, C.M.; Alessandrini, A.; Erikson, R.L. The primary structure of MEK, a protein kinase that phosphorylates the ERK gene product. Science 1992, 258, 478–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, D.M.; Boxer, K.; Ha, B.H.; Tkacik, E.; Levitz, T.; Rawson, S.; Metivier, R.J.; Schmoker, A.; Jeon, H.; Eck, M.J.; et al. Cryo-EM structures of CRAF/MEK1/14-3-3 complexes in autoinhibited and open-monomer states reveal features of RAF regulation. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 8150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Nicolet, J. Specificity models in MAPK cascade signaling. FEBS Open Bio 2023, 13, 1177–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, P.T.C.; Garnett, M.J.; Roe, S.M.; Lee, S.; Niculescu-Duvaz, D.; Good, V.M.; Jones, C.M.; Marshall, C.J.; Springer, C.J.; Barford, D.; et al. Mechanism of activation of the RAF-ERK signaling pathway by oncogenic mutations of B-RAF. Cell 2004, 116, 855–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, H.; Bignell, G.R.; Cox, C.; Stephens, P.; Edkins, S.; Clegg, S.; Teague, J.; Woffendin, H.; Garnett, M.J.; Bottomley, W.; et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature 2002, 417, 949–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hingorani, S.R.; Wang, L.; Multani, A.S.; Combs, C.; Deramaudt, T.B.; Hruban, R.H.; Rustgi, A.K.; Chang, S.; Tuveson, D.A. Trp53R172H and KrasG12D cooperate to promote chromosomal instability and widely metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocacinoma in mice. Cancer Cell 2005, 7, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Vega, F.; Mina, M.; Armenia, J.; Chatila, W.K.; Luna, A.; La, K.C.; Dimitriadoy, S.; Liu, D.L.; Kantheti, H.S.; Saghafinia, S.; et al. Oncogenic Signaling Pathways in The Cancer Genome Atlas. Cell 2018, 173, 321–337.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, E.L.; Willis, N.; Mercer, K.; Bronson, R.T.; Crowley, D.; Montoya, R.; Jacks, T.; Tuveson, D.A. Analysis of lung tumor initiation and progression using conditional expression of oncogenic K-ras. Genes Dev. 2001, 15, 3243–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Genomic classification of cutaneous melanoma. Cell 2015, 161, 1681–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Rauch, J.; Kolch, W. Targeting MAPK signaling in cancer: Mechanisms of drug resistance and sensitivity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahar, M.E.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, D.R. Targeting the RAS/RAF/MAPK pathway for cancer therapy: From mechanism to clinical studies. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2023, 8, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazel, D.; Nagasaka, M. The development of amivantamab for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Respir. Res. 2023, 24, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salles, D.; Santino, S.F.; Ribeiro, D.A.; Malinverni, A.C.M.; Stávale, J.N. The involvement of the MAPK pathway in pilocytic astrocytomas. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2022, 232, 153821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez Almaraz, E.; Guerra, G.A.; Al-Adli, N.N.; Young, J.S.; Dada, A.; Quintana, D.; Taylor, J.W.; Oberheim-Bush, N.A.; Clarke, J.L.; Butowski, N.A.; et al. Longitudinal profiling of IDH-mutant astrocytomas reveals acquired RAS-MAPK pathway mutations associated with inferior survival. Neurooncol. Adv. 2025, 7, vdaf024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ma, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, J.; Zhao, L.; Huang, Q.; Li, S.; Fang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Type II RAF inhibitor tovorafenib for the treatment of pediatric low-grade glioma. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2024, 17, 999–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Bondra, K.M.; Wang, H.; Kurmashev, D.; Mukherjee, B.; Kanji, S.; Habib, A.A.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, S.; Burma, S.; et al. Dual inhibition of MAPK and TORC1 signaling retards development of radiation resistance in pediatric BRAFV600E glioma models. Neuro Oncol. 2025, 27, 1787–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beylerli, O.; Gareev, I.; Musaev, E.; Roumiantsev, S.; Chekhonin, V.; Ahmad, A.; Chao, Y.; Yang, G. New approaches to targeted drug therapy of intracranial tumors. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigaud, R.; Brummer, T.; Kocher, D.; Milde, T.; Selt, F. MOST wanted: Navigating the MAPK-OIS-SASP-tumor microenvironment axis in primary pediatric low-grade glioma and preclinical models. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2024, 40, 3209–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; DeYoung, T.; Ressler, H.; Chandler, W. Brain tumors: Development, drug resistance, and sensitization—An epigenetic approach. Epigenetics 2023, 18, 2237761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuksis, M.; Gao, Y.; Tran, W.; Hoey, C.; Kiss, A.; Komorowski, A.S.; Dhaliwal, A.J.; Sahgal, A.; Das, S.; Chan, K.K.; et al. The incidence of brain metastases among patients with metastatic breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuro Oncol. 2021, 23, 894–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillespie, C.S.; Mustafa, M.A.; Richardson, G.E.; Alam, A.M.; Lee, K.S.; Hughes, D.M.; Escriu, C.; Zakaria, R. Genomic alterations and the incidence of brain metastases in advanced and metastatic NSCLC: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2023, 18, 1703–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahm, F.; Brandner, S.; Bertero, L.; Capper, D.; French, P.J.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Giangaspero, F.; Haberler, C.; Hegi, M.E.; Kristensen, B.W.; et al. Molecular diagnostic tools for the World Health Organization (WHO) 2021 classification of gliomas, glioneuronal and neuronal tumors; an EANO guideline. Neuro Oncol. 2023, 25, 1731–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malbari, F. Pediatric neuro-oncology. Neurol. Clin. 2021, 39, 829–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bale, T.A.; Rosenblum, M.K. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: An update on pediatric low-grade gliomas and glioneuronal tumors. Brain Pathol. 2022, 32, e13060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gritsch, S.; Batchelor, T.T.; Gonzalez Castro, L.N.G. Diagnostic, therapeutic, and prognostic implications of the 2021 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system. Cancer 2022, 128, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocasio, J.K.; Budd, K.M.; Roach, J.T.; Andrews, J.M.; Baker, S.J. Oncohistones and disrupted development in pediatric-type diffuse high-grade glioma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2023, 42, 367–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; McEachron, T.A.; Schwartzentruber, J.; Wu, G. Histone H3 mutations in pediatric brain tumors. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2014, 6, a018689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstock, J.D.; Kang, K.-D.; Klinger, N.V.; Olsen, H.E.; Gary, S.; Totsch, S.K.; Ghajar-Rahimi, G.; Segar, D.; Thompson, E.M.; Darley-Usmar, V.; et al. Targeting oncometabolism to maximize immunotherapy in brain tumors. Oncogene 2022, 41, 2663–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckel-Passow, J.E.; Lachance, D.H.; Molinaro, A.M.; Walsh, K.M.; Decker, P.A.; Sicotte, H.; Pekmezci, M.; Rice, T.; Kosel, M.L.; Smirnov, I.V.; et al. Glioma groups based on 1p/19q, IDH, and TERT promoter mutations in tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2499–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.P.; Spiller, S.E.; Barker, E.D. Drug penetration in pediatric brain tumors: Challenges and opportunities. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2021, 68, e28983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aryal, M.; Porter, T. Emerging therapeutic strategies for brain tumors. Neuromolecular Med. 2022, 24, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Ali, H.; Lathia, J.D.; Chen, P. Immunotherapy for glioblastoma: Current state, challenges, and future perspectives. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2024, 21, 1354–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khabibov, M.; Garifullin, A.; Boumber, Y.; Khaddour, K.; Fernandez, M.; Khamitov, F.; Khalikova, L.; Kuznetsova, N.; Kit, O.; Kharin, L. Signaling pathways and therapeutic approaches in glioblastoma multiforme. Int. J. Oncol. 2022, 60, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Pollard, K.; Allen, A.N.; Tomar, T.; Pijnenburg, D.; Yao, Z.; Rodriguez, F.J.; Pratilas, C.A. Combined inhibition of SHP2 and MEK is effective in models of NF1-deficient malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 5367–5379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Jacob, S.; Kurupi, R.; Dalton, K.M.; Coon, C.; Greninger, P.; Egan, R.K.; Stein, G.T.; Murchie, E.; McClanaghan, J.; et al. High-risk neuroblastoma with NF1 loss of function is targetable using SHP2 inhibition. Cell Rep. 2022, 40, 111095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, A.; Musket, A.; Musich, P.R.; Schweitzer, J.B.; Xie, Q. Receptor tyrosine kinases as druggable targets in glioblastoma: Do signaling pathways matter? Neurooncol. Adv. 2021, 3, vdab133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baez-Rodriguez, S.M.; Ciubotaru, G.V.; Onose, G.; Sevastre, A.-S.; Sfredel, V.; Danoiu, S.; Dricu, A.; Tataranu, L.G. An overview of EGFR mechanisms and their implications in targeted therapies for glioblastoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaak, R.G.W.; Hoadley, K.A.; Purdom, E.; Wang, V.; Qi, Y.; Wilkerson, M.D.; Miller, C.R.; Ding, L.; Golub, T.; Mesirov, J.P.; et al. Integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell 2010, 17, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghabkari, A.; Huang, B.; Park, M. Aberrant MET receptor tyrosine kinase signaling in glioblastoma: Targeted therapy and future directions. Cells 2024, 13, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro Stucklin, A.S.; Ryall, S.; Fukuoka, K.; Zapotocky, M.; Lassaletta, A.; Li, C.; Bridge, T.; Kim, B.; Arnoldo, A.; Kowalski, P.E.; et al. Alterations in ALK/ROS1/NTRK/MET drive a group of infantile hemispheric gliomas. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picca, A.; Sansone, G.; Santonocito, O.S.; Mazzanti, C.M.; Sanson, M.; Di Stefano, A.L. Diffuse gliomas with FGFR3-TACC3 fusions: Oncogenic mechanisms, hallmarks, and therapeutic perspectives. Cancers 2023, 15, 5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambella, A.; Senetta, R.; Collemi, G.; Vallero, S.G.; Monticelli, M.; Cofano, F.; Zeppa, P.; Garbossa, D.; Pellerino, A.; Rudà, R.; et al. NTRK fusions in central nervous system tumors: A rare, but worthy target. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D.T.W.; Hutter, B.; Jäger, N.; Korshunov, A.; Kool, M.; Warnatz, H.J.; Zichner, T.; Lambert, S.R.; Ryzhova, M.; Quang, D.A.K.; et al. Recurrent somatic alterations of FGFR1 and NTRK2 in pilocytic astrocytoma. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 927–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauziède-Espariat, A.; Beccaria, K.; Dangouloff-Ros, V.; Sievers, P.; Meurgey, A.; Pissaloux, D.; Appay, R.; Saffroy, R.; Grill, J.; Mariet, C.; et al. A comprehensive analysis of infantile central nervous system tumors to improve distinctive criteria for infant-type hemispheric glioma versus desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma/astrocytoma. Brain Pathol. 2023, 33, e13182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Xie, J.; He, H.; Li, H.; Tang, X.; Wang, S.; Li, Z.; Tian, Y.; Li, L.; Zhu, J.; et al. Phase separation underlies signaling activation of oncogenic NTRK fusions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2219589120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drilon, A.; Jenkins, C.; Iyer, S.; Schoenfeld, A.; Keddy, C.; Davare, M.A. ROS1-dependent cancers: Biology, diagnostics and therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network; Brat, D.J.; Verhaak, R.G.W.; Aldape, K.D.; Yung, W.K.; Salama, S.R.; Cooper, L.A.; Rheinbay, E.; Miller, C.R.; Vitucci, M.; et al. Comprehensive, integrative genomic analysis of diffuse lower-grade gliomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2481–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature 2008, 455, 1061–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Duan, Y.; Wei, D.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, J.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Zhou, J.; Liu, Z.; Jin, Z.; et al. Molecular features of pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma. Hum. Pathol. 2019, 86, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Markegard, E.; Dharmaiah, S.; Urisman, A.; Drew, M.; Esposito, D.; Scheffzek, K.; Nissley, D.V.; McCormick, F.; Simanshu, D.K. Structural insights into the SPRED1-neurofibromin-KRAS complex and disruption of SPRED1-neurofibromin interaction by oncogenic EGFR. Cell Rep. 2020, 32, 107909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steklov, M.; Pandolfi, S.; Baietti, M.F.; Batiuk, A.; Carai, P.; Najm, P.; Zhang, M.; Jang, H.; Renzi, F.; Cai, Y.; et al. Mutations in LZTR1 drive human disease by dysregulating RAS ubiquitination. Science 2018, 362, 1177–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, C.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, J.; Shen, G.; Yu, R. A Hg(2+)-mediated label-free fluorescent sensing strategy based on G-quadruplex formation for selective detection of glutathione and cysteine. Analyst 2013, 138, 1713–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siebel, A.; Cubillos-Rojas, M.; Santos, R.C.; Schneider, T.; Bonan, C.D.; Bartrons, R.; Ventura, F.; de Oliveira, J.R.; Rosa, J.L. Contribution of S6K1/MAPK signaling pathways in the response to oxidative stress: Activation of RSK and MSK by hydrogen peroxide. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P.K.S.; Li, J.; Jeong, K.J.; Shao, S.; Chen, H.; Tsang, Y.H.; Sengupta, S.; Wang, Z.; Bhavana, V.H.; Tran, R.; et al. Systematic functional annotation of somatic mutations in cancer. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 450–462.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.T.W.; Kocialkowski, S.; Liu, L.; Pearson, D.M.; Bäcklund, L.M.; Ichimura, K.; Collins, V.P. Tandem duplication producing a novel oncogenic BRAF fusion gene defines the majority of pilocytic astrocytomas. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 8673–8677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievert, A.J.; Jackson, E.M.; Gai, X.; Hakonarson, H.; Judkins, A.R.; Resnick, A.C.; Sutton, L.N.; Storm, P.B.; Shaikh, T.H.; Biegel, J.A. Duplication of 7q34 in pediatric low-grade astrocytomas detected by high-density SNP-based arrays results in a novel BRAF fusion gene. Brain Pathol. 2009, 19, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forshew, T.; Tatevossian, R.G.; Lawson, A.R.J.; Ma, J.; Neale, G.; Ogunkolade, B.W.; Jones, T.A.; Aarum, J.; Dalton, J.; Bailey, S.; et al. Activation of the ERK/MAPK pathway: A signature genetic defect in posterior fossa pilocytic astrocytomas. J. Pathol. 2009, 218, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurani, H.; Gurav, M.; Shetty, O.; Chinnaswamy, G.; Moiyadi, A.; Gupta, T.; Jalali, R.; Epari, S. Pilocytic astrocytomas: BRAFV600E and BRAF fusion expression patterns in pediatric and adult age groups. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2019, 35, 1525–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, G.; Miller, C.P.; Tatevossian, R.G.; Dalton, J.D.; Tang, B.; Orisme, W.; Punchihewa, C.; Parker, M.; Qaddoumi, I.; et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies genetic alterations in pediatric low-grade gliomas. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomić, T.T.; Olausson, J.; Wilzén, A.; Sabel, M.; Truvé, K.; Sjögren, H.; Dósa, S.; Tisell, M.; Lannering, B.; Enlund, F.; et al. A new GTF2I-BRAF fusion mediating MAPK pathway activation in pilocytic astrocytoma. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanrahan, A.J.; Solit, D.B. BRAF—A tumour-agnostic drug target with lineage-specific dependencies. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 21, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulikakos, P.I.; Sullivan, R.J.; Yaeger, R. Molecular pathways and mechanisms of BRAF in cancer therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 4618–4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karoulia, Z.; Wu, Y.; Ahmed, T.A.; Xin, Q.; Bollard, J.; Krepler, C.; Wu, X.; Zhang, C.; Bollag, G.; Herlyn, M.; et al. An Integrated Model of RAF Inhibitor Action Predicts Inhibitor Activity against Oncogenic BRAF Signaling. Cancer Cell 2016, 30, 501–503, Erratum in Cancer Cell 2016, 30, 485–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2016.06.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, N.J.; Novak, B.; Liu, Z.; Cavallo, M.; Gunderwala, A.Y.; Connolly, M.; Wang, Z. Analyses of the Oncogenic BRAF D594G Variant Reveal a Kinase-Independent Function of BRAF in Activating MAPK Signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 2407–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yde, C.W.; Sehested, A.; Mateu-Regué, À.; Østrup, O.; Scheie, D.; Nysom, K.; Nielsen, F.C.; Rossing, M. A new NFIA:RAF1 fusion activating the MAPK pathway in pilocytic astrocytoma. Cancer Genet. 2016, 209, 440–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Fierst, T.M.; Han, H.J.; Smith, T.E.; Vakil, A.; Storm, P.B.; Resnick, A.C.; Waanders, A.J. CRAF gene fusions in pediatric low-grade gliomas define a distinct drug response based on dimerization profiles. Oncogene 2017, 36, 6348–6358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degirmenci, U.; Wang, M.; Hu, J. Targeting aberrant RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK signaling for cancer therapy. Cells 2020, 9, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakubov, R.; Kaloti, R.; Persaud, P.; McCracken, A.; Zadeh, G.; Bunda, S. It’s all downstream from here: RTK/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway resistance mechanisms in glioblastoma. J. Neurooncol. 2025, 172, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, H.M.; McKenna, L.R.; Espinoza, V.L.; Pozdeyev, N.; Pike, L.A.; Sams, S.B.; LaBarbera, D.; Reigan, P.; Raeburn, C.D.; Schweppe, R.E.; et al. Inhibition of BRAF and ERK1/2 has synergistic effects on thyroid cancer growth in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Carcinog. 2021, 60, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, D.M.; Puzanov, I.; Subbiah, V.; Faris, J.E.; Chau, I.; Blay, J.-Y.; Wolf, J.; Raje, N.; Diamond, E.L.; Hollebecque, A.; et al. Vemurafenib in multiple nonmelanoma cancers with BRAF V600 mutations. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaley, T.; Touat, M.; Subbiah, V.; Hollebecque, A.; Rodon, J.; Lockhart, A.C.; Keedy, V.; Bielle, F.; Hofheinz, R.D.; Joly, F.; et al. BRAF Inhibition in BRAFV600-Mutant Gliomas: Results from the VE-BASKET Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 3477–3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, G.W.; Orr, B.A.; Gajjar, A. Complete Clinical Regression of a BRAF V600E-Mutant Pediatric Glioblastoma Multiforme after BRAF Inhibitor Therapy. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolaides, T.; Nazemi, K.J.; Crawford, J.; Kilburn, L.; Minturn, J.; Gajjar, A.; Gauvain, K.; Leary, S.; Dhall, G.; Aboian, M.; et al. Phase I Study of Vemurafenib in Children with Recurrent or Progressive BRAFV600E Mutant Brain Tumors: Pacific Pediatric Neuro-Oncology Consortium Study (PNOC-002). Oncotarget 2020, 11, 1942–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidhyanathan, S.; Mittapalli, R.K.; Sarkaria, J.N.; Elmquist, W.F. Factors Influencing the CNS Distribution of a Novel MEK-1/2 Inhibitor: Implications for Combination Therapy for Melanoma Brain Metastases. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2014, 42, 1292–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbato, M.I.; Nashed, J.; Bradford, D.; Ren, Y.; Khasar, S.; Miller, C.P.; Zolnik, B.S.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y.; Bi, Y.; et al. U.S. FDA approval summary: Dabrafenib in combination with trametinib for BRAF V600E mutation-positive low-grade glioma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.F.; Carter, T.; Kitchen, N.; Mulholland, P. Dabrafenib and trametinib in BRAFV600E mutated glioma. CNS Oncol. 2017, 6, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delord, J.P.; Robert, C.; Nyakas, M.; McArthur, G.A.; Kudchakar, R.; Mahipal, A.; Yamada, Y.; Sullivan, R.; Arance, A.; Kefford, R.F.; et al. Phase I Dose-Escalation and -Expansion Study of the BRAF Inhibitor Encorafenib (LGX818) in Metastatic BRAF-Mutant Melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 5339–5348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreck, K.C.; Strowd, R.E.; Nabors, L.B.; Ellingson, B.M.; Chang, M.; Tan, S.K.; Abdullaev, Z.; Turakulov, R.; Aldape, K.; Danda, N.; et al. Response rate and molecular correlates to encorafenib and binimetinib in BRAF-V600E–mutant high-grade glioma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 2048–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gan, C.; Sparidans, R.W.; Wagenaar, E.; van Hoppe, S.; Beijnen, J.H.; Schinkel, A.H. P-Glycoprotein (MDR1/ABCB1) and Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (BCRP/ABCG2) Affect Brain Accumulation and Intestinal Disposition of Encorafenib in Mice. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 129, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.B.; Quade, B.; Schenk, N.; Fang, Z.; Zingg, M.; Cohen, S.E.; Swalm, B.M.; Li, C.; Özen, A.; Ye, C.; et al. The pan-RAF-MEK nondegrading molecular glue NST-628 is a potent and brain-penetrant inhibitor of the RAS-MAPK pathway with activity across diverse RAS- and RAF-driven cancers. Cancer Discov. 2024, 14, 1190–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, C.; Karaszewska, B.; Schachter, J.; Rutkowski, P.; Mackiewicz, A.; Stroiakovski, D.; Lichinitser, M.; Dummer, R.; Grange, F.; Mortier, L.; et al. Improved Overall Survival in Melanoma with Combined Dabrafenib and Trametinib. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planchard, D.; Smit, E.F.; Groen, H.J.M.; Mazieres, J.; Besse, B.; Helland, Å.; Giannone, V.; D’Amelio, A.M., Jr.; Zhang, P.; Mookerjee, B.; et al. Dabrafenib plus Trametinib in Patients with Previously Untreated BRAFV600E-Mutant Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: An Open-Label, Phase 2 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1307–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subbiah, V.; Kreitman, R.J.; Wainberg, Z.A.; Cho, J.Y.; Schellens, J.H.M.; Soria, J.C.; Wen, P.Y.; Zielinski, C.; Cabanillas, M.E.; Urbanowitz, G.; et al. Dabrafenib and Trametinib Treatment in Patients with Locally Advanced or Metastatic BRAF V600-Mutant Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, D.; Demko, S.; Sinha, A.; Mishra-Kalyani, P.S.; Shen, Y.L.; Khasar, S.; Goheer, M.A.; Helms, W.S.; Pan, L.; Xu, Y.; et al. FDA approval summary: Selumetinib for plexiform neurofibroma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 4142–4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Hysinger, J.D.; Barron, T.; Schindler, N.F.; Cobb, O.; Guo, X.; Yalçın, B.; Anastasaki, C.; Mulinyawe, S.B.; Ponnuswami, A.; et al. NF1 mutation drives neuronal activity-dependent initiation of optic glioma. Nature 2021, 594, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, C.; Ahmed, T.A.; Tucker, M.R.; Ung, P.M.U.; Xiao, M.; Karoulia, Z.; Amabile, A.; Wu, X.; Aaronson, S.A.; Ang, C.; et al. Exploiting allosteric properties of RAF and MEK inhibitors to target therapy-resistant tumors driven by oncogenic BRAF signaling. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 1716–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fangusaro, J.; Onar-Thomas, A.; Poussaint, T.Y.; Wu, S.; Ligon, A.H.; Lindeman, N.; Banerjee, A.; Packer, R.J.; Kilburn, L.B.; Goldman, S.; et al. Selumetinib in paediatric patients with BRAF-aberrant or neurofibromatosis type 1-associated recurrent, refractory, or progressive low-grade glioma: A multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fangusaro, J.; Onar-Thomas, A.; Poussaint, T.Y.; Wu, S.; Ligon, A.H.; Lindeman, N.; Campagne, O.; Banerjee, A.; Gururangan, S.; Kilburn, L.B.; et al. A phase II trial of selumetinib in children with recurrent optic pathway and hypothalamic low-grade glioma without NF1: A Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium study. Neuro Oncol. 2021, 23, 1777–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fangusaro, J.; Onar-Thomas, A.; Poussaint, T.Y.; Lensing, S.; Ligon, A.H.; Lindeman, N.; Banerjee, A.; Kilburn, L.B.; Lenzen, A.; Pillay-Smiley, N.; et al. A Phase 2 PBTC Study of Selumetinib for Recurrent/Progressive Pediatric Low-Grade Glioma: Strata 2, 5, and 6 with Long-Term Outcomes on Strata 1, 3, and 4. Neuro Oncol. 2025, 27, 2415–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, P.Y.; Stein, A.; van den Bent, M.; De Greve, J.; Wick, A.; de Vos, F.Y.F.L.; von Bubnoff, N.; van Linde, M.E.; Lai, A.; Prager, G.W.; et al. Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with BRAFV600E-mutant low-grade and high-grade glioma (ROAR): A multicenter, open-label, single-arm, phase 2, basket trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perreault, S.; Larouche, V.; Tabori, U.; Hawkin, C.; Lippé, S.; Ellezam, B.; Décarie, J.C.; Théoret, Y.; Métras, M.É.; Sultan, S.; et al. A phase 2 study of trametinib for patients with pediatric glioma or plexiform neurofibroma with refractory tumor and activation of the MAPK/ERK pathway: TRAM-01. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilcox, J.A.; Boire, A.A. Leveraging Molecular and Immune-Based Therapies in Leptomeningeal Metastases. CNS Drugs 2023, 37, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touat, M.; Smith, K.A.; Freese, K.; Poussaint, T.Y.; Wallace, D.W.; Parker, N.R.; Qaddoumi, I.; Stewart, C.F.; Fangusaro, J.; Patel, K.S.; et al. Vemurafenib and cobimetinib overcome resistance to vemurafenib in BRAF-mutant ganglioglioma. Neurology 2018, 91, 523–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoy, S.M. Mirdametinib: First Approval. Drugs 2025, 85, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moertel, C.L.; Hirbe, A.C.; Shuhaiber, H.H.; Bielamowicz, K.; Sidhu, A.; Viskochil, D.; Weber, M.D.; Lokku, A.; Smith, L.M.; Foreman, N.K.; et al. ReNeu: A pivotal, phase IIb trial of mirdametinib in adults and children with symptomatic neurofibromatosis 1-associated plexiform neurofibroma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, JCO2401034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, B.S.; Durinck, S.; Stawiski, E.W.; Yin, J.; Wang, W.; Lin, E.; Moffat, J.; Martin, S.E.; Modrusan, Z.; Seshagiri, S.; et al. ERK Mutations and Amplification Confer Resistance to ERK-Inhibitor Therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 4044–4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigaud, R.; Rösch, L.; Gatzweiler, C.; Benzel, J.; von Soosten, L.; Peterziel, H.; Selt, F.; Najafi, S.; Ayhan, S.; Gerloff, X.F.; et al. The first-in-class ERK inhibitor ulixertinib shows promising activity in mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-driven pediatric low-grade glioma models. Neuro Oncol. 2023, 25, 566–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.A.; Adamopoulos, C.; Karoulia, Z.; Wu, X.; Sachidanandam, R.; Aaronson, S.A.; Poulikakos, P.I. SHP2 Drives Adaptive Resistance to ERK Signaling Inhibition in Molecularly Defined Subsets of ERK-Dependent Tumors. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 65–78.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sait, S.F.; Tang, K.H.; Angus, S.P.; Brown, R.; Sun, D.; Xie, X.; Iltis, C.; Lien, M.; Socci, N.D.; Bale, T.A.; et al. Hydroxychloroquine prevents resistance and potentiates the antitumor effect of SHP2 inhibition in NF1-associated malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2407745121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, Y.; Hou, Y.; Cheng, R.; Zheng, L.; Xu, M.; Zhang, X.; Yang, N.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y. Targeting PDGFRα-Activated Glioblastoma through Specific Inhibition of SHP2-Mediated Signaling. Neuro Oncol. 2019, 21, 1423–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossauer, S.; Koeck, K.; Murphy, N.E.; Meyers, I.D.; Daynac, M.; Truffaux, N.; Truong, A.Y.; Nicolaides, T.P.; McMahon, M.; Berger, M.S.; et al. Concurrent MEK targeted therapy prevents MAPK pathway reactivation during BRAFV600E targeted inhibition in a novel syngeneic murine glioma model. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 75839–75853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hare, P.; Cooney, T.; de Blank, P.; Gutmann, D.H.; Kieran, M.; Milde, T.; Fangusaro, J.; Fisher, M.J.; Avula, S.; Packer, R.; et al. Resistance, rebound, and recurrence regrowth patterns in pediatric low-grade glioma treated by MAPK inhibition: A modified Delphi approach to build international consensus-based definitions-International Pediatric Low-Grade Glioma Coalition. Neuro Oncol. 2024, 26, 1357–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouffet, E.; Hansford, J.R.; Garrè, M.L.; Hara, J.; Plant-Fox, A.; Aerts, I.; Locatelli, F.; van der Lugt, J.; Papusha, L.; Sahm, F.; et al. Dabrafenib plus trametinib in pediatric glioma with BRAF V600 mutations. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1108–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, J.; Liu, Y.; Fan, Y. The effects of dabrafenib and/or trametinib treatment in Braf V600-mutant glioma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg Rev. 2024, 47, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algazi, A.P.; Moon, J.; Lao, C.D.; Chmielowski, B.; Kendra, K.L.; Lewis, K.D.; Gonzalez, R.; Kim, K.; Godwin, J.E.; Curti, B.D.; et al. A Phase 1 Study of Triple-Targeted Therapy with BRAF, MEK, and AKT Inhibitors for Patients with BRAF-Mutated Cancers. Cancer 2024, 130, 1784–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, R.S.; Canoutas, D.A.; Stuhlmiller, T.J.; Dhruv, H.D.; Irvin, D.M.; Bash, R.E.; Angus, S.P.; Herring, L.E.; Simon, J.M.; Skinner, K.R.; et al. Combination Therapy with Potent PI3K and MAPK Inhibitors Overcomes Adaptive Kinome Resistance to Single Agents in Preclinical Models of Glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2017, 19, 1469–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Fernandez, N.R.; Levine, A.; Bianchi, V.; Stengs, L.K.; Chung, J.; Negm, L.; Dimayacyac, J.R.; Chang, Y.; Nobre, L.; et al. Combined immunotherapy improves outcome for replication-repair-deficient high-grade glioma failing anti–PD-1 monotherapy: A report from the International RRD Consortium. Cancer Discov. 2024, 14, 258–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, D.T.; Piris, A.; Cogdill, A.P.; Cooper, Z.A.; Lezcano, C.; Ferrone, C.R.; Mitra, D.; Boni, A.; Newton, L.P.; Liu, C.; et al. BRAF Inhibition Is Associated with Enhanced Melanoma Antigen Expression and a More Favorable Tumor Microenvironment in Patients with Metastatic Melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 1225–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capogiri, M.; De Micheli, A.J.; Lassaletta, A.; Muñoz, D.P.; Coppé, J.P.; Mueller, S.; Guerreiro Stucklin, A.S. Response and Resistance to BRAFV600E Inhibition in Gliomas: Roadblocks Ahead? Front. Oncol. 2023, 12, 1074726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, P.Y.M.; Lam, T.-C.; Pu, J.K.S.; Li, L.-F.; Leung, R.C.Y.; Ho, J.M.K.; Zhung, J.T.F.; Wong, B.; Chan, T.S.K.; Loong, H.H.F.; et al. Regression of BRAF V600E mutant adult glioblastoma after primary combined BRAF–MEK inhibitor targeted therapy: A report of two cases. Oncotarget 2019, 10, 3818–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbour, G.; Ellezam, B.; Weil, A.G.; Cayrol, R.; Vanan, M.I.; Coltin, H.; Larouche, V.; Erker, C.; Jabado, N.; Perreault, S.; et al. Upfront BRAF/MEK inhibitors for treatment of high-grade glioma: A case report and review of the literature. Neuro Oncol. Adv. 2022, 4, vdac174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusco, M.J.; Piña, Y.; Macaulay, R.J.; Sahebjam, S.; Forsyth, P.A.; Peguero, E.; Walko, C.M. Durable progression-free survival with the use of BRAF and MEK inhibitors in four cases with BRAF V600E-mutated gliomas. Cancer Control 2021, 28, 10732748211040013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pekmezci, M.; Villanueva-Meyer, J.E.; Goode, B.; Van Ziffle, J.; Onodera, C.; Grenert, J.P.; Bastian, B.C.; Chamyan, G.; Maher, O.M.; Khatib, Z.; et al. The Genetic Landscape of Ganglioglioma. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2018, 6, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, D.; Garg, C.; Singla, N.; Radotra, B.D. Desmoplastic Non-Infantile Astrocytoma/Ganglioglioma: Rare Low-Grade Tumor with Frequent BRAF V600E Mutation. Hum. Pathol. 2018, 80, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, I.; Agnihotri, S.; Broniscer, A. Childhood Brain Tumours: Current Management, Biological Insights and Future Directions. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2019, 23, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoranjan, B.; Venugopal, C.; McFarlane, N.; Doble, B.W.; Dunn, S.E.; Scheinemann, K.; Singh, S.K. Medulloblastoma Stem Cells: Where Development and Cancer Cross Pathways. Pediatr. Res. 2012, 71, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merve, A.; Dubuc, A.M.; Zhang, X.; Remke, M.; Baxter, P.A.; Li, X.N.; Taylor, M.D.; Marino, S. Polycomb Group Gene BMI1 Controls Invasion of Medulloblastoma Cells and Inhibits BMP-Regulated Cell Adhesion. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2014, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badodi, S.; Pomella, N.; Lim, Y.M.; Brandner, S.; Morrison, G.; Pollard, S.M.; Zhang, X.; Zabet, N.R.; Marino, S. Combination of BMI1 and MAPK/ERK Inhibitors Is Effective in Medulloblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2022, 24, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilburn, L.B.; Khuong-Quang, D.-A.; Hansford, J.R.; Landi, D.; van der Lugt, J.; Leary, S.E.S.; Driever, P.H.; Bailey, S.; Perreault, S.; McCowage, G.; et al. The type II RAF inhibitor tovorafenib in relapsed/refractory pediatric low-grade glioma: The phase 2 FIREFLY-1 trial. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardridge, W.M. The Blood–Brain Barrier: Bottleneck in Brain Drug Development. NeuroRx 2005, 2, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, N.J.; Rönnbäck, L.; Hansson, E. Astrocyte–Endothelial Interactions at the Blood–Brain Barrier. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 7, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arvanitis, C.D.; Ferraro, G.B.; Jain, R.K. The Blood–Brain Barrier and Blood–Tumour Barrier in Brain Tumours and Metastases. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groothuis, D.R. The Blood–Brain and Blood–Tumor Barriers: A Review of Strategies for Increasing Drug Delivery. Neuro Oncol. 2000, 2, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Tellingen, O.; Yetkin-Arik, B.; de Gooijer, M.C.; Wesseling, P.; Wurdinger, T.; de Vries, H.E. Overcoming the Blood–Brain Tumor Barrier for Effective Glioblastoma Treatment. Drug Resist. Updat. 2015, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittapalli, R.K.; Vaidhyanathan, S.; Sane, R.; Elmquist, W.F. Impact of P-Glycoprotein (ABCB1) and Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (ABCG2) on the Brain Distribution of a Novel BRAF Inhibitor: Vemurafenib (PLX4032). J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2012, 342, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osswald, M.; Blaes, J.; Liao, Y.; Solecki, G.; Gömmel, M.; Berghoff, A.S.; Salphati, L.; Wallin, J.J.; Phillips, H.S.; Wick, W.; et al. Impact of Blood–Brain Barrier Integrity on Tumor Growth and Therapy Response in Brain Metastases. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 6078–6087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacy, A.E.; Jansson, P.J.; Richardson, D.R. Molecular Pharmacology of ABCG2 and Its Role in Chemoresistance. Mol. Pharmacol. 2013, 84, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Zepeda, D.; Taghi, M.; Scherrmann, J.M.; Decleves, X.; Menet, M.C. ABC Transporters at the Blood–Brain Interfaces, Their Study Models, and Drug Delivery Implications in Gliomas. Pharmaceutics 2019, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Sane, R.; Gallardo, J.L.; Ohlfest, J.R.; Elmquist, W.F. Distribution of Gefitinib to the Brain Is Limited by P-Glycoprotein (ABCB1) and Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (ABCG2)-Mediated Active Efflux. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2010, 334, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, N.A.; Buckle, T.; Zhao, J.; Beijnen, J.H.; Schellens, J.H.; van Tellingen, O. Restricted Brain Penetration of the Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Erlotinib Due to the Drug Transporters P-Gp and BCRP. Investig. New Drugs 2012, 30, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batra, U.; Lokeshwar, N.; Gupta, S.; Shirsath, P. Role of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in the Management of Central Nervous System Metastases in EGFR Mutation-Positive Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Indian J. Cancer 2017, 54, S37–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Chen, Z.; Franke, R.; Orwick, S.; Zhao, M.; Rudek, M.A.; Sparreboom, A.; Baker, S.D. Interaction of the Multikinase Inhibitors Sorafenib and Sunitinib with Solute Carriers and ATP-Binding Cassette Transporters. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 6062–6069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Gooijer, M.C.; Zhang, P.; Weijer, R.; Buil, L.C.M.; Beijnen, J.H.; van Tellingen, O. The Impact of P-Glycoprotein and Breast Cancer Resistance Protein on the Brain Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of a Panel of MEK Inhibitors. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 142, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gampa, G.; Kim, M.; Cook-Rostie, N.; Laramy, J.K.; Sarkaria, J.N.; Paradiso, L.; DePalatis, L.; Elmquist, W.F. Brain Distribution of a Novel MEK Inhibitor E6201: Implications in the Treatment of Melanoma Brain Metastases. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2018, 46, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabari, J.K.; Velcheti, V.; Shimizu, K.; Strickland, M.R.; Heist, R.S.; Singh, M.; Nayyar, N.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Digumarthy, S.R.; Gainor, J.F.; et al. Activity of Adagrasib (MRTX849) in Brain Metastases: Preclinical Models and Clinical Data from Patients with KRASG12C-Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 3318–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijmers, J.; Retmana, I.A.; Bui, V.; Arguedas, D.; Lebre, M.C.; Sparidans, R.W.; Beijnen, J.H.; Schinkel, A.H. ABCB1 Attenuates Brain Exposure to the KRASG12C Inhibitor Opnurasib Whereas Binding to Mouse Carboxylesterase 1c Influences Its Plasma Exposure. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 175, 116720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbinski, C. To BRAF or Not to BRAF: Is That Even a Question Anymore? J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2013, 72, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryall, S.; Zapotocky, M.; Fukuoka, K.; Nobre, L.; Guerreiro Stucklin, A.; Bennett, J.; Siddaway, R.; Li, C.; Pajovic, S.; Arnoldo, A.; et al. Integrated Molecular and Clinical Analysis of 1,000 Pediatric Low-Grade Gliomas. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 569–583.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lhermitte, B.; Wolf, T.; Chenard, M.P.; Coca, A.; Todeschi, J.; Proust, F.; Hirsch, E.; Schott, R.; Noel, G.; Guerin, E.; et al. Molecular Heterogeneity in BRAF-Mutant Gliomas: Diagnostic, Prognostic, and Therapeutic Implications. Cancers 2023, 15, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazo De La Vega, L.; Comeau, H.; Sallan, S.; Al-Ibraheemi, A.; Gupta, H.; Li, Y.Y.; Tsai, H.K.; Kang, W.; Ward, A.; Church, A.J.; et al. Rare FGFR Oncogenic Alterations in Sequenced Pediatric Solid and Brain Tumors Suggest FGFR Is a Relevant Molecular Target in Childhood Cancer. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2022, 6, e2200390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.E.; Park, C.K.; Kim, S.K.; Phi, J.H.; Paek, S.H.; Choi, J.Y.; Kang, H.J.; Lee, J.H.; Won, J.K.; Yun, H.; et al. NTRK-Fused Central Nervous System Tumours: Clinicopathological and Genetic Insights and Response to TRK Inhibitors. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2024, 12, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, B.J.A.; Oba-Shinjo, S.M.; de Almeida, A.N.; Marie, S.K.N. Molecular Alterations in Meningiomas: Literature Review. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2019, 176, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vamvoukaki, R.; Chrysoulaki, M.; Betsi, G.; Xekouki, P. Pituitary Tumorigenesis—Implications for Management. Medicina 2023, 59, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.H.; Brastianos, P.K. Genetic Characterization of Brain Metastases in the Era of Targeted Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2017, 7, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz, T.P.; Mason, W.P. BRAF Mutations in CNS Tumors—Prognostic Markers and Therapeutic Targets. CNS Drugs 2023, 37, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Richmond, A.; Yan, C. Immunomodulatory Properties of PI3K/AKT/mTOR and MAPK/MEK/ERK Inhibition Augment Response to Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Melanoma and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergholz, J.S.; Zhao, J.J. How Compensatory Mechanisms and Adaptive Rewiring Have Shaped Our Understanding of Therapeutic Resistance in Cancer. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 6074–6077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddick, G.; Kotliarova, S.; Rodriguez, V.; Kim, H.S.; Linkous, A.; Storaska, A.J.; Ahn, S.; Walling, J.; Belova, G.; Fine, H.A. A Core Regulatory Circuit in Glioblastoma Stem Cells Links MAPK Activation to a Transcriptional Program of Neural Stem Cell Identity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, A.; Wu, W.; Bivona, T.G. Targeting Oncogenic BRAF: Past, Present, and Future. Cancers 2019, 11, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma ecology theory: Cancer as multidimensional spatiotemporal “unity of ecology and evolution” pathological ecosystem. Theranostics 2023, 13, 1607–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, W.; Chen, J.Q.; Liu, C.; Malu, S.; Creasy, C.; Tetzlaff, M.T.; Xu, C.; McKenzie, J.A.; Zhang, C.; Liang, X.; et al. Loss of PTEN Promotes Resistance to T Cell-Mediated Immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, M.A.; de Carné Trécesson, S.; Rana, S.; Zecchin, D.; Moore, C.; Molina-Arcas, M.; East, P.; Spencer-Dene, B.; Nye, E.; Barnouin, K.; et al. Oncogenic RAS Signaling Promotes Tumor Immunoresistance by Stabilizing PD-L1 mRNA. Immunity 2017, 47, 1083–1099.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lailler, C.; Louandre, C.; Morisse, M.C.; Lhossein, T.; Godin, C.; Lottin, M.; Constans, J.M.; Chauffert, B.; Galmiche, A.; Saidak, Z. ERK1/2 Signaling Regulates the Immune Microenvironment and Macrophage Recruitment in Glioblastoma. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39, BSR20191433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Liu, C.; Hu, A.; Zhang, D.; Yang, H.; Mao, Y. Understanding the immunosuppressive microenvironment of glioma: Mechanistic insights and clinical perspectives. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 17, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigaud, R.; Albert, T.K.; Hess, C.; Hielscher, T.; Winkler, N.; Kocher, D.; Walter, C.; Münter, D.; Selt, F.; Usta, D.; et al. MAPK inhibitor sensitivity scores predict sensitivity driven by the immune infiltration in pediatric low-grade gliomas. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.L.; Panovska, D.; Park, J.W.; Grossauer, S.; Koeck, K.; Bui, B.; Nasajpour, E.; Nirschl, J.J.; Feng, Z.P.; Cheung, P.; et al. BRAF/MEK Inhibition Induces Cell State Transitions Boosting Immune Checkpoint Sensitivity in BRAFV600E-Mutant Glioma. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 102183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.J.; Khandelwal, G.; Baenke, F.; Cannistraci, A.; Macleod, K.; Mundra, P.; Ashton, G.; Mandal, A.; Viros, A.; Gremel, G.; et al. Brain Microenvironment-Driven Resistance to Immune and Targeted Therapies in Acral Melanoma. ESMO Open 2020, 5, e000707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, D.; Ruggiero, A.; Amato, M.; Maurizi, P.; Riccardi, R. BRAF and MEK inhibitors in pediatric glioma: New therapeutic strategies, new toxicities. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2016, 12, 1397–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, A.; Mrowczynski, O.D.; Greene, A.; Ryan, S.; Chung, C.; Zacharia, B.E.; Glantz, M. Dual BRAF/MEK inhibitor therapy in BRAF V600E-mutated primary brain tumors: A case series showing dramatic clinical and radiographic responses and a reduction in cutaneous toxicity. J. Neurosurg. 2019, 133, 1704–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Zhong, C.S.; Kieran, M.W.; Chi, S.N.; Wright, K.D.; Huang, J.T. Cutaneous reactions to targeted therapies in children with CNS tumors: A cross-sectional study. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2019, 66, e27682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berzero, G.; Bellu, L.; Baldini, C.; Ducray, F.; Guyon, D.; Eoli, M.; Silvani, A.; Dehais, C.; Idbaih, A.; Younan, N.; et al. Sustained Tumor Control with MAPK Inhibition in BRAF V600-Mutant Adult Glial and Glioneuronal Tumors. Neurology 2021, 97, e673–e683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selt, F.; van Tilburg, C.M.; Bison, B.; Sievers, P.; Harting, I.; Ecker, J.; Pajtler, K.W.; Sahm, F.; Bahr, A.; Simon, M.; et al. Response to trametinib treatment in progressive pediatric low-grade glioma patients. J. Neurooncol. 2020, 149, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robison, N.J.; Su, J.A.; Fang, M.J.; Malvar, J.; Menteer, J. Cardiac function in children and young adults treated with MEK inhibitors: A retrospective cohort study. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2022, 43, 1223–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, A.V.; Robinson, G.W.; Gauvain, K.; Basu, E.M.; Macy, M.E.; Maese, L.; Whipple, N.S.; Sabnis, A.J.; Foster, J.H.; Shusterman, S.; et al. Entrectinib in children and young adults with solid or primary CNS tumors harboring NTRK, ROS1, or ALK aberrations (STARTRK-NG). Neuro Oncol. 2022, 24, 1776–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doz, F.; van Tilburg, C.M.; Geoerger, B.; Højgaard, M.; Øra, I.; Boni, V.; Capra, M.; Chisholm, J.; Chung, H.C.; DuBois, S.G.; et al. Efficacy and safety of larotrectinib in TRK fusion-positive primary central nervous system tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2022, 24, 997–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, A.V.; Bagchi, A.; Armstrong, A.E.; van Tilburg, C.M.; Basu, E.M.; Robinson, G.W.; Wang, H.; Casanova, M.; André, N.; Campbell-Hewson, Q.; et al. Efficacy and safety of entrectinib in children with extracranial solid or central nervous system (CNS) tumours harbouring NTRK or ROS1 fusions. Eur. J. Cancer 2025, 220, 115308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felistia, Y.; Wen, P.Y. Molecular profiling and targeted therapies in gliomas. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2023, 23, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, H.; Kong, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Luo, T.; Jiang, Y. Targeting mTOR for cancer therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundstrøm, T.; Prestegarden, L.; Azuaje, F.; Aasen, S.N.; Røsland, G.V.; Varughese, J.K.; Bahador, M.; Bernatz, S.; Braun, Y.; Harter, P.N.; et al. Inhibition of mitochondrial respiration prevents BRAF-mutant melanoma brain metastasis. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2019, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, E.; Kara, H.G.; Kosova, B.; Cetintas, V.B. Targeting Apoptosis to Overcome Chemotherapy Resistance. In Metastasis; Sergi, C.M., Ed.; Exon Publications: Brisbane, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medikonda, R.; Dunn, G.; Rahman, M.; Fecci, P.; Lim, M. A review of glioblastoma immunotherapy. J. Neurooncol. 2021, 151, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadowski, K.; Jażdżewska, A.; Kozłowski, J.; Zacny, A.; Lorenc, T.; Olejarz, W. Revolutionizing glioblastoma treatment: A comprehensive overview of modern therapeutic approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berghoff, A.S.; Kiesel, B.; Widhalm, G.; Rajky, O.; Ricken, G.; Wöhrer, A.; Hackl, M.; Birner, P.; Hainfellner, J.A.; Preusser, M. Programmed death ligand 1 expression and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2015, 17, 1064–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Wang, J.; Deng, X.; Xiong, F.; Ge, J.; Xiang, B.; Wu, X.; Ma, J.; Zhou, M.; Li, X.; et al. Role of the tumor microenvironment in PD-L1/PD-1-mediated tumor immune escape. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; Song, G.; Yu, J. The Prognostic Significance of PD-L1 Expression in Patients with Glioma: A Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zeng, Y.; Tan, Q.; Huang, Z.; Jia, J.; Jiang, G. Efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors versus chemotherapy in lung cancer with brain metastases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Immunol. Res. 2022, 2022, 4518898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Song, Y.; Gu, L.; Wang, Y.; Ma, W. Insight into the progress in CAR-T cell therapy and combination with other therapies for glioblastoma. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2023, 16, 4121–4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwani, F.; Patil, P.; Jain, K. Unlocking glioblastoma: Breakthroughs in molecular mechanisms and next-generation therapies. Med. Oncol. 2025, 42, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewski, W.; Sanchez-Perez, L.; Gajewski, T.F.; Sampson, J.H. Brain Tumor Microenvironment and Host State: Implications for Immunotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 4202–4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, N.; Wu, W.; Wang, Z.; Dai, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Peng, Y.; et al. Glioma targeted therapy: Insight into future of molecular approaches. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowforth, O.D.; Brannigan, J.; El Khoury, M.; Sarathi, C.I.P.; Bestwick, H.; Bhatti, F.; Mair, R. Personalised therapeutic approaches to glioblastoma: A systematic review. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 116104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojica, C.V.; Gutierrez, K.M.E.; Mason, W.P. Advances in IDH-mutant glioma management: IDH inhibitors, clinical implications of INDIGO trial, and future perspectives. Future Oncol. 2025, 21, 2089–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Drug/Strategy | Molecular Target(s) | CNS Tumor Type(s) | Key Clinical Findings | Selected Trials |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dabrafenib + Trametinib | BRAF V600E + MEK1/2 | Pediatric LGG, HGG, PXA, GBM | ORR > 70% in BRAF V600E pLGG; significant PFS improvement; FDA-approved for pLGG (2023) | NCT07110246, NCT03919071 |

| Vemurafenib | BRAF V600E | Glioma, PXA | Partial responses; limited durability due to resistance; modest BBB penetration | NCT01748149 |

| Encorafenib (+ MEK inhibitors) | BRAF V600E | Glioma (investigational) | Improved pharmacodynamics vs. vemurafenib; CNS efficacy under study | NCT03973918 |

| Selumetinib | MEK1/2 | NF1-associated pLGG, OP glioma | Tumor shrinkage and visual improvement; durable disease control; FDA-approved for NF1 tumors | NCT01089101, NCT03871257 |

| Trametinib | MEK1/2 | pLGG, NF1 tumors, PXA | Clinical benefit in pLGG and PNs; enhanced efficacy with dabrafenib | NCT03363217 |

| Mirdametinib | MEK1/2 | NF1 tumors, pLGG | Recently FDA-approved for NF1-associated PN; promising CNS activity | NCT04923126 |

| Tovorafenib | RAF | Relapsed pLGG with BRAF alterations | High response rate; effective in BRAF-fusion tumors; FDA-approved 2024 | FIREFLY-1/NCT04775485 |

| NST-628 | RAF-MEK molecular glue | RAS/RAF-mutant gliomas | Potent, brain-penetrant MAPK suppression; preclinical efficacy | Preclinical |

| Ulixertinib | ERK1/2 | Advanced glioma (investigational) | Activity in BRAF/MEK-resistant tumors; BBB penetration | NCT01781429 |

| SHP2 inhibitors (TNO155, RMC-4630) | SHP2 | GBM, NF1-MPNST | Suppress upstream RAS activation; synergy with TMZ * | NCT03114319 |

| Agent (Target) | Tumor Type | Age | Study Name/ Clinical Trial ID | Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dabrafenib * and trametinib ± | BRAF V600-mutant pLGG | 12 months–25 years old | NCT07110246 | Phase II |

| Dabrafenib * and trametinib | Several CNS tumors | 1–99 years old | NCT03975829 | Phase IV |

| Dabrafenib, trametinib ± and nivolumab ⊥ | BRAF-altered pediatric glioma | 1–26 years old | NCT06712875 | Phase I/II |

| Dabrafenib * and trametinib ± | HGG (among other cancer types) | 18–100 years old | NCT03340506 | Phase IV |

| Dabrafenib * and trametinib ± | HGG | 3–25 years old | NCT03919071 | Phase II |

| Dabrafenib, trametinib ± and HQ ∝ | LGG or HGG with BRAF aberration LGG with NF1 | 1–30 years old | NCT04201457 | Phase I/II |

| Mirdametinib ± | LGG | 2–24 years old | NCT04923126 | Phase I/II |

| Mirdametinib ± | LGG, activation of MAPK | 2–24 years old | NCT06666348 | Phase I/II |

| Selumetinib ± | Recurrent/refractory LGG, OP/HG glioma, NF1, PA | 3–21 years old | NCT01089101 | Phase I/II |

| Selumetinib ± | Progressive LGG | 2–25 years old | NCT04576117 | Phase III |

| Selumetinib ± | NF1, LGG | 2–21 years old | NCT03871257 | Phase III |

| Selumetinib ± | LGG | 2–21 years old | NCT04166409 | Phase III |

| Trametinib ± | LGG | 1 month–25 years old | NCT05180825 | Phase II |

| Trametinib ± | LGG, NF1, PN, activation of the MAPK/ERK pathway | 1–25 years old | NCT03363217 | Phase II |

| Trametinib ± and everolimus ∇ | LGG, HGG | 1–25 years old | NCT04485559 | Phase I |

| Tovorafenib * | Relapsed/refractory LGG with BRAF alterations | 6 months–25 years old | FIREFLY-1/NCT04775485 | Phase II |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vrachas, D.; Kosma, E.; Giannopoulou, A.-I.; Margoni, A.; Gargalionis, A.N.; El-Habr, E.A.; Piperi, C.; Adamopoulos, C. Targeting the MAPK Pathway in Brain Tumors: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cancers 2026, 18, 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010156

Vrachas D, Kosma E, Giannopoulou A-I, Margoni A, Gargalionis AN, El-Habr EA, Piperi C, Adamopoulos C. Targeting the MAPK Pathway in Brain Tumors: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):156. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010156

Chicago/Turabian StyleVrachas, Dimitrios, Elisavet Kosma, Angeliki-Ioanna Giannopoulou, Angeliki Margoni, Antonios N. Gargalionis, Elias A. El-Habr, Christina Piperi, and Christos Adamopoulos. 2026. "Targeting the MAPK Pathway in Brain Tumors: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities" Cancers 18, no. 1: 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010156

APA StyleVrachas, D., Kosma, E., Giannopoulou, A.-I., Margoni, A., Gargalionis, A. N., El-Habr, E. A., Piperi, C., & Adamopoulos, C. (2026). Targeting the MAPK Pathway in Brain Tumors: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cancers, 18(1), 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010156