Three-Year Outcomes of Neoadjuvant Chemoimmunotherapy vs. Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy in Resectable Esophageal Cancer: A Multicenter Retrospective Study

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Methods and Patients

2.2. Treatments

2.3. Endpoints and Assessments

2.4. Statistical Analysis

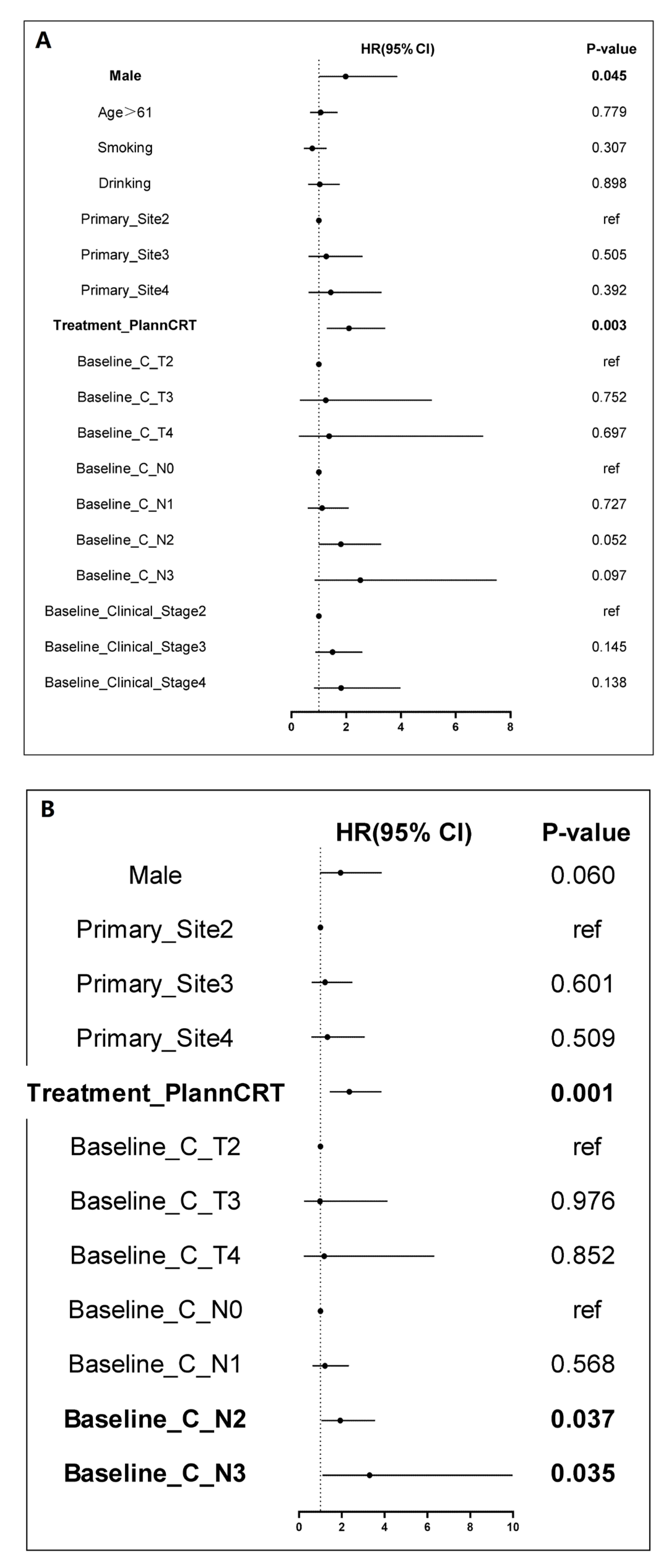

3. Results

3.1. Patient Clinical Characteristics

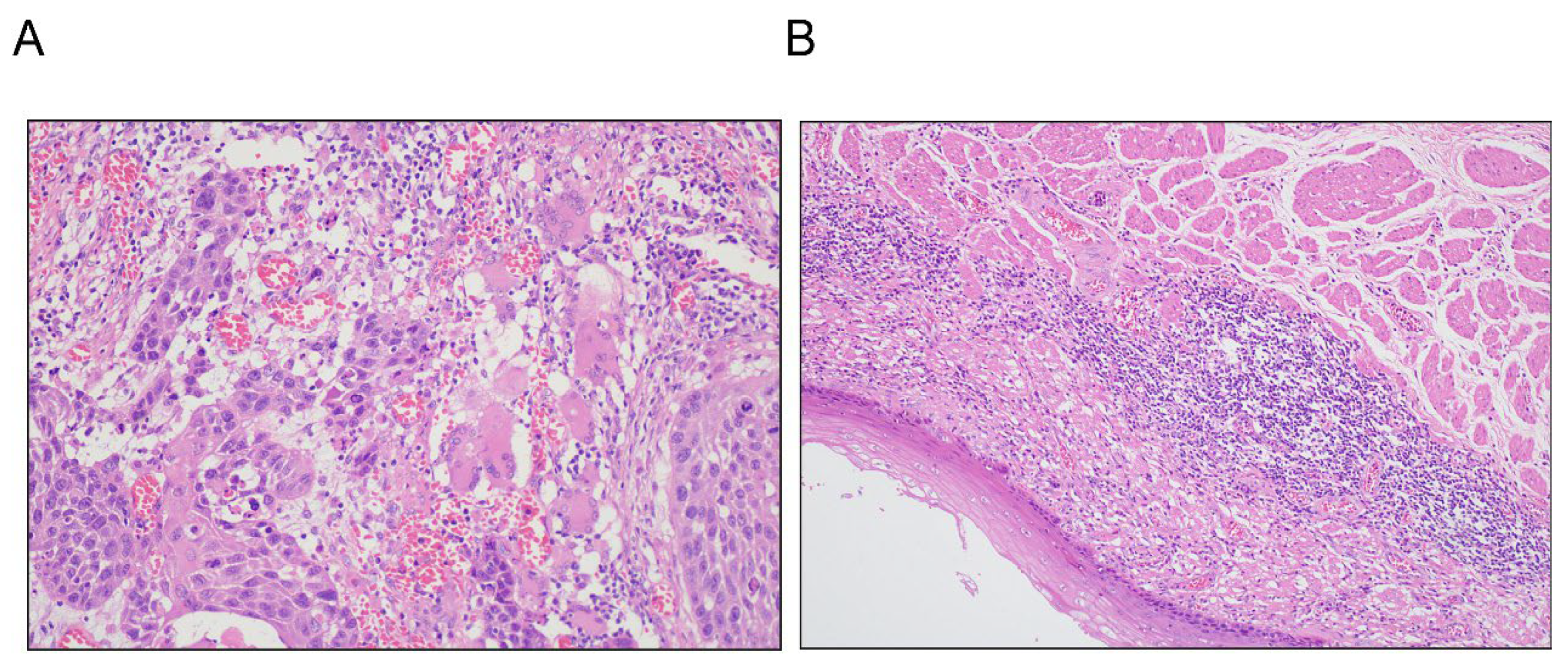

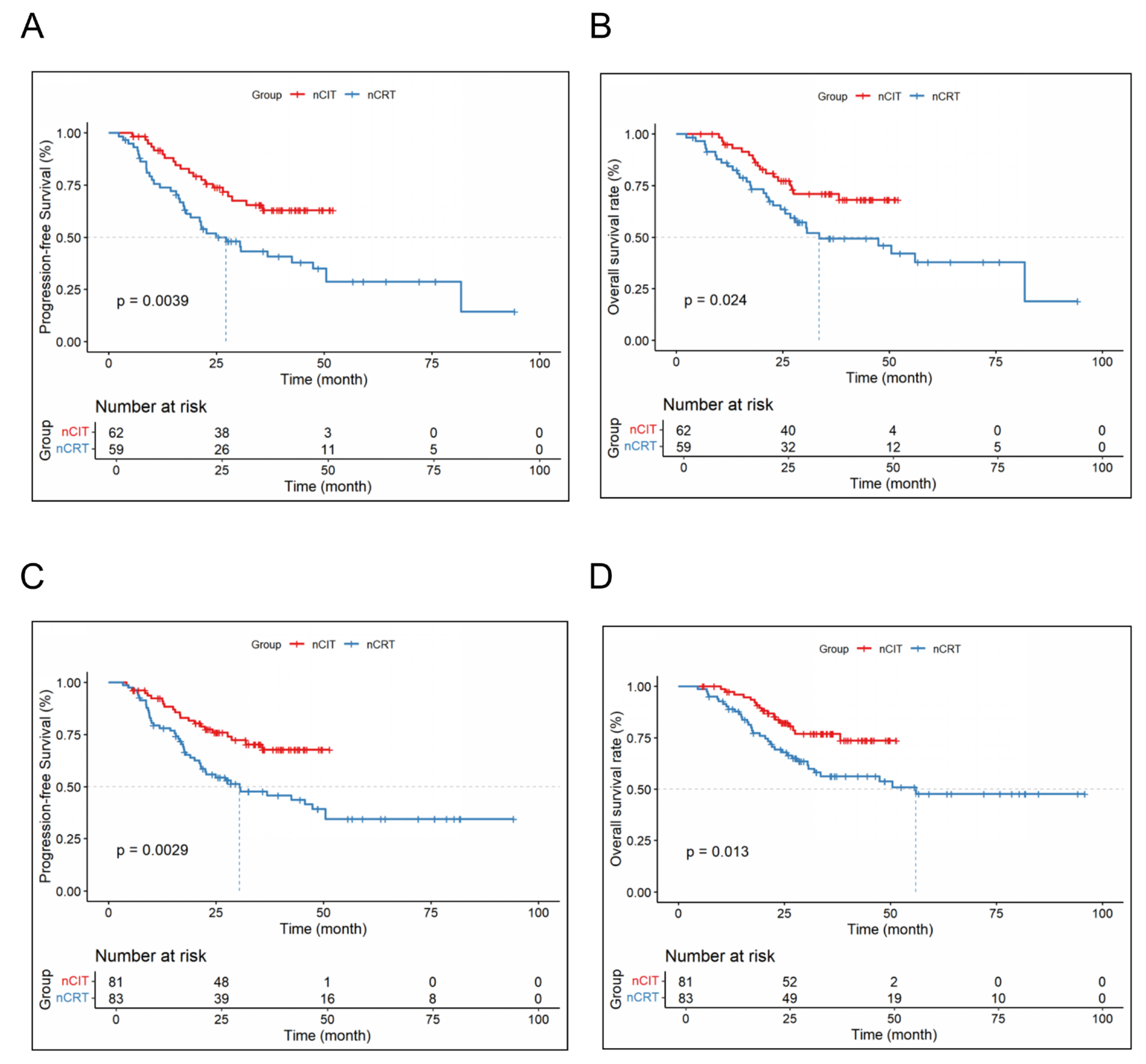

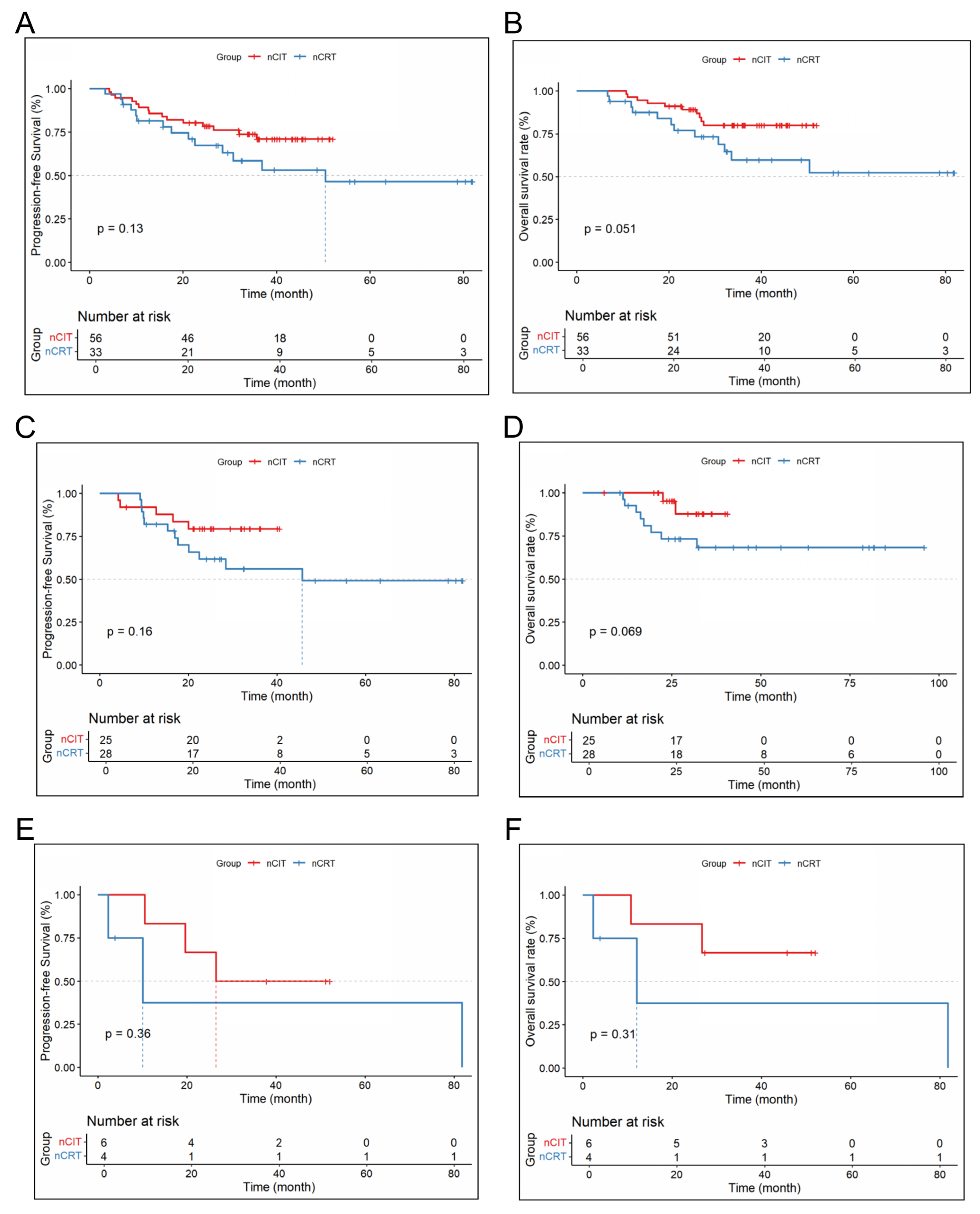

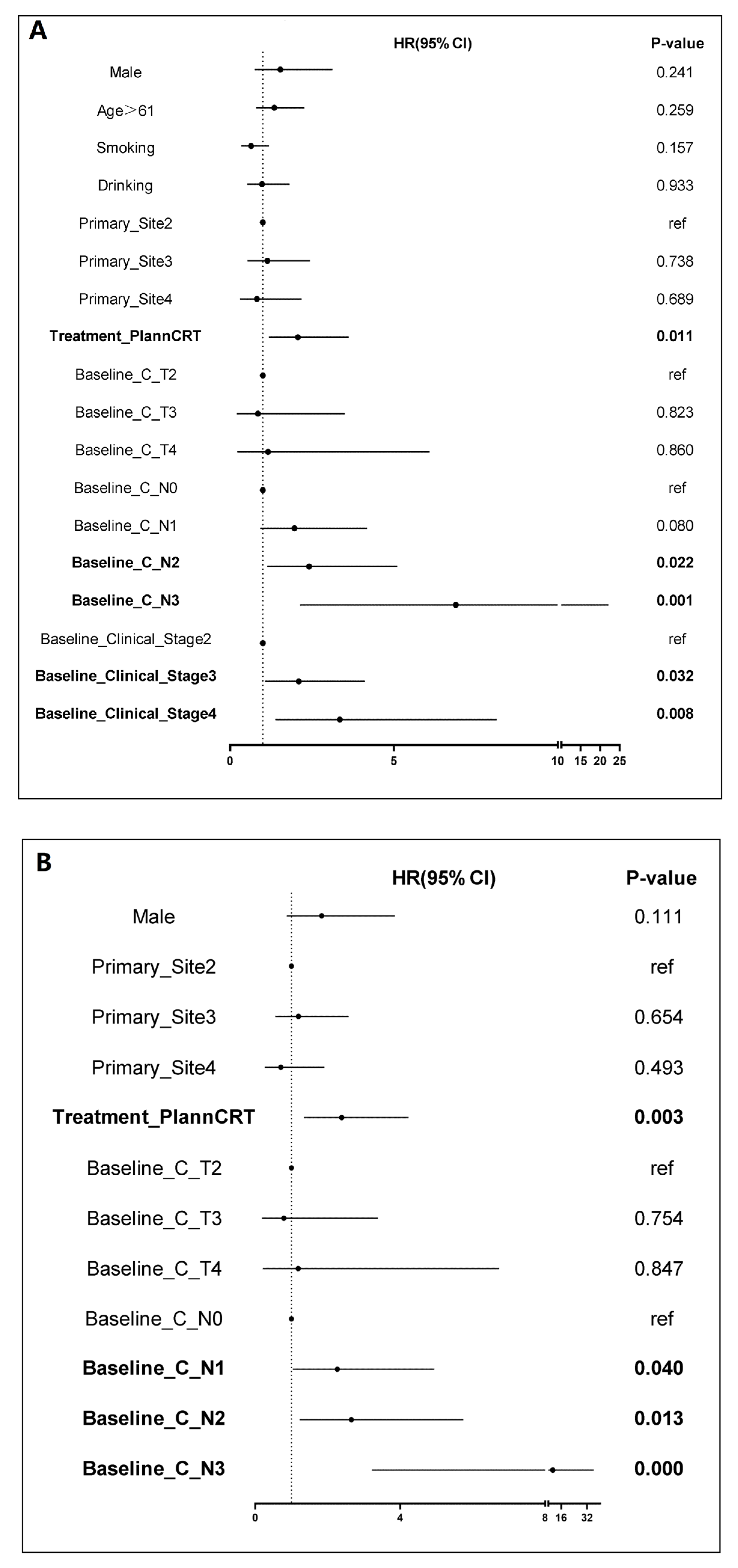

3.2. Efficacy Results

3.3. Safety Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LA-ESCC | Locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma |

| ESCC | Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma |

| nCRT | Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy |

| nCIT | Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus immunotherapy |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| DFS | Disease-free survival |

| pCR | Pathologic complete response |

| ORR | Objective response rate |

| MPR | Major pathological response |

| PSM | Propensity score matching |

| TP | Taxane plus platinum |

| TRAEs | Treatment-related adverse events |

| AEs | Adverse events |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death-ligand 1 |

| TMB | Tumor mutational burden |

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennathur, A.; Gibson, M.K.; Jobe, B.A.; Luketich, J.D. Oesophageal carcinoma. Lancet 2013, 381, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, X.F.; Daiko, H.; Han, Y.T.; Mao, Y.S. Optimal preoperative neoadjuvant therapy for resectable locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2020, 1482, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyck, B.M.; van Lanschot, J.J.B.; Hulshof, M.C.C.M.; van der Wilk, B.J.; Shapiro, J.; van Hagen, P.; van Berge Henegouwen, M.I.; Wijnhoven, B.P.L.; van Laarhoven, H.W.M.; Nieuwenhuijzen, G.A.P.; et al. Ten-Year Outcome of Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy Plus Surgery for Esophageal Cancer: The Randomized Controlled CROSS Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 1995–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, J.; van Lanschot, J.J.B.; Hulshof, M.C.C.M.; van Hagen, P.; van Berge Henegouwen, M.I.; Wijnhoven, B.P.L.; van Laarhoven, H.W.M.; Nieuwenhuijzen, G.A.P.; Hospers, G.A.P.; Bonenkamp, J.J.; et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy plus surgery versus surgery alone for oesophageal or junctional cancer (CROSS): Long-term results of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 1090–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, N.; Kato, H.; Igaki, H.; Shinoda, M.; Ozawa, S.; Shimizu, H.; Nakamura, T.; Yabusaki, H.; Aoyama, N.; Kurita, A.; et al. A randomized trial comparing postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil versus preoperative chemotherapy for localized advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus (JCOG9907). Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 19, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.M.; Shen, L.; Shah, M.A.; Enzinger, P.; Adenis, A.; Doi, T.; Kojima, T.; Metges, J.P.; Li, Z.; Kim, S.B.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for first-line treatment of advanced oesophageal cancer (KEYNOTE-590): A randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet 2021, 398, 1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ready, N.E.; Ott, P.A.; Hellmann, M.D.; Zugazagoitia, J.; Hann, C.L.; de Braud, F.; Antonia, S.J.; Ascierto, P.A.; Moreno, V.; Atmaca, A.; et al. Nivolumab Monotherapy and Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab in Recurrent Small Cell Lung Cancer: Results from the CheckMate 032 Randomized Cohort. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2020, 15, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, P.A.; Hu-Lieskovan, S.; Chmielowski, B.; Govindan, R.; Naing, A.; Bhardwaj, N.; Margolin, K.; Awad, M.M.; Hellmann, M.D.; Lin, J.J.; et al. A Phase Ib Trial of Personalized Neoantigen Therapy Plus Anti-PD-1 in Patients with Advanced Melanoma, Non-small Cell Lung Cancer, or Bladder Cancer. Cell 2020, 183, 347–362.e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Emens, L.A. Chemoimmunotherapy: Reengineering tumor immunity. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2013, 62, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharabi, A.B.; Lim, M.; DeWeese, T.L.; Drake, C.G. Radiation and checkpoint blockade immunotherapy: Radiosensitisation and potential mechanisms of synergy. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, e498–e509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, X.; Zhao, G.; Liang, F.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, W.; Liu, L.; Li, R.; Duan, X.; Ma, Z.; Yue, J.; et al. Safety and effectiveness of pembrolizumab combined with paclitaxel and cisplatin as neoadjuvant therapy followed by surgery for locally advanced resectable (stage III) esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: A study protocol for a prospective, single-arm, single-center, open-label, phase-II trial (Keystone-001). Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Meng, H.; Ling, X.; Wang, X.; Xin, Y.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, L.; Fang, C.; Liang, H.; et al. Neoadjuvant camrelizumab combined with paclitaxel and nedaplatin for locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: A single-arm phase 2 study (cohort study). Int. J. Surg. 2024, 110, 1430–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, D.; Liu, J.; Sun, J.; Lu, M.; Wang, R.; Hui, B.; Li, X.; Zhou, C.; et al. Neoadjuvant sintilimab and chemotherapy in patients with potentially resectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (KEEP-G 03): An open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e005830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetzlaff, M.T.; Messina, J.L.; Stein, J.E.; Xu, X.; Amaria, R.N.; Blank, C.U.; van de Wiel, B.A.; Ferguson, P.M.; Rawson, R.V.; Ross, M.I.; et al. Pathological assessment of resection specimens after neoadjuvant therapy for metastatic melanoma. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 1861–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, N.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Ma, Q.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, Q.; Lu, C.; Tian, J.; Wang, Z.; Tang, H.; et al. Pathological Response and Tumor Immune Microenvironment Remodeling Upon Neoadjuvant ALK-TKI Treatment in ALK-Rearranged Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Target. Oncol. 2023, 18, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Biau, J.; Sun, X.S.; Sire, C.; Martin, L.; Alfonsi, M.; Prevost, J.B.; Modesto, A.; Lafond, C.; Tourani, J.M.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus cetuximab concurrent with radiotherapy in patients with locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck unfit for cisplatin (GORTEC 2015-01 PembroRad): A multicenter, randomized, phase II trial. Ann Oncol. 2023, 34, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reifeis, S.A.; Hudgens, M.G. On Variance of the Treatment Effect in the Treated When Estimated by Inverse Probability Weighting. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 191, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, P.M.; Spicer, J.; Lu, S.; Provencio, M.; Mitsudomi, T.; Awad, M.M.; Felip, E.; Broderick, S.R.; Brahmer, J.R.; Swanson, S.J.; et al. Neoadjuvant Nivolumab plus Chemotherapy in Resectable Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1973–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P.; Cortes, J.; Dent, R.; Pusztai, L.; McArthur, H.; Kümmel, S.; Bergh, J.; Denkert, C.; Park, Y.H.; Hui, R.; et al. Event-free Survival with Pembrolizumab in Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.-K.; Meng, F.-Y.; Wei, X.-F.; Chen, X.K.; Li, H.M.; Liu, Q.; Li, C.J.; Xie, H.N.; Xu, L.; Zhang, R.X.; et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy versus neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in patients with locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2024, 168, 417–428.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Hao, S.; Tian, J.; Li, Y.; Han, D. Comparison of Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy Plus Chemotherapy versus Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy for Patients with Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Propensity Score Matching Study. J. Inflamm. Res. 2023, 16, 3351–3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, H.; Hu, C.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y.; Ji, G.; Ge, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, M. Lymph node metastasis in cancer progression: Molecular mechanisms, clinical significance and therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Z.-N.; Gao, L.; Weng, K.; Huang, Z.; Han, W.; Kang, M. Safety and Feasibility of Esophagectomy Following Combined Immunotherapy and Chemotherapy for Locally Advanced Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Propensity Score Matching Analysis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 836338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, L.; Wu, B.; Chen, Y.; He, H.; Li, C.; Lin, W.; Lin, J. Perioperative outcomes of neoadjuvant immunotherapy plus chemotherapy and neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in the treatment of locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: A retrospective comparative cohort study. J. Thorac. Dis. 2023, 15, 1279–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.-T.; Chirieac, L.R.; Abraham, S.C.; Krasinskas, A.M.; Wang, H.; Rashid, A.; Correa, A.M.; Hofstetter, W.L.; Ajani, J.A.; Swisher, S.G. Excellent Interobserver Agreement on Grading the Extent of Residual Carcinoma After Preoperative Chemoradiation in Esophageal and Esophagogastric Junction Carcinoma: A Reliable Predictor for Patient Outcome. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2007, 31, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortazar, P.; Zhang, L.; Untch, M.; Mehta, K.; Costantino, J.P.; Wolmark, N.; Bonnefoi, H.; Cameron, D.; Gianni, L.; Valagussa, P.; et al. Pathological complete response and long-term clinical benefit in breast cancer: The CTNeoBC pooled analysis. Lancet 2014, 384, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shitara, K.; Rha, S.Y.; Wyrwicz, L.S.; Oshima, T.; Karaseva, N.; Osipov, M.; Yasui, H.; Yabusaki, H.; Afanasyev, S.; Park, Y.K.; et al. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in locally advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal cancer (KEYNOTE-585): An interim analysis of the multicentre, double-blind, randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2024, 25, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenza, C.; Saldanha, E.F.; Gong, Y.; De Placido, P.; Gritsch, D.; Ortiz, H.; Trapani, D.; Conforti, F.; Cremolini, C.; Peters, S.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA clearance as a predictive biomarker of pathologic complete response in patients with solid tumors treated with neoadjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Yang, X.; Yin, J.; Shen, Y.; Tan, L. Validity of Using Pathological Response as a Surrogate for Overall Survival in Neoadjuvant Studies for Esophageal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 30, 7461–7471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Baseline Feature, n (%) | nCRT (n = 87) | nCIT (n = 138) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.927 | ||

| male | 70 (80.5) | 113 (81.9) | |

| female | 17 (19.5) | 25 (18.1) | |

| Age (years old) | 0.047 | ||

| ≤61 | 53 (60.9) | 64 (46.4) | |

| >61 | 34 (39.1) | 74 (53.6) | |

| Smoking | 0.003 | ||

| no | 65 (74.7) | 75 (54.3) | |

| yes | 22 (25.3) | 63 (45.7) | |

| Drinking | 0.153 | ||

| no | 70 (80.5) | 98 (71.0) | |

| yes | 17 (19.5) | 40 (29.0) | |

| Tumor site | 0.031 | ||

| upper throacic segment | 12 (13.8) | 16 (11.6) | |

| middle thoracic segment | 64 (73.6) | 84 (60.9) | |

| lower thoracic segment | 11 (12.6) | 38 (27.5) | |

| Clinical T stage | 0.008 | ||

| T1 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.4) | |

| T2 | 3 (3.4) | 20 (14.5) | |

| T3 | 79 (90.8) | 100 (72.5) | |

| T4 | 5 (5.7) | 16 (11.6) | |

| Clinical N stage | 0.131 | ||

| N0 | 28 (32.2) | 32 (23.2) | |

| N1 | 31 (35.6) | 40 (29.0) | |

| N2 | 25 (28.7) | 57 (41.3) | |

| N3 | 3 (3.4) | 9 (6.5) | |

| Clinical stage | 0.174 | ||

| I | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | |

| II | 30 (34.5) | 33 (23.9) | |

| III | 49 (56.3) | 81 (58.7) | |

| IV | 8 (9.2) | 23 (16.7) |

| Baseline Feature, n (%) | nCRT (n = 87) | nCIT (n = 87) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.852 | ||

| male | 70 (80.5) | 68 (78.2) | |

| female | 17 (19.5) | 19 (21.8) | |

| Age (years old) | 0.285 | ||

| ≤61 | 53 (60.9) | 45 (51.7) | |

| >61 | 34 (39.1) | 42 (48.3) | |

| Smoking | 0.318 | ||

| no | 65 (74.7) | 58 (66.7) | |

| yes | 22 (25.3) | 29 (33.3) | |

| Drinking | 0.582 | ||

| no | 70 (80.5) | 66 (75.9) | |

| yes | 17 (19.5) | 21 (24.1) | |

| Tumor site | 0.465 | ||

| upper thoracic segment | 12 (13.8) | 11 (12.6) | |

| middle thoracic segment | 64 (73.6) | 59 (67.8) | |

| lower thoracic segment | 11 (12.6) | 17 (19.5) | |

| Clinical T stage | 0.953 | ||

| T2 | 3 (3.4) | 3 (3.4) | |

| T3 | 79 (90.8) | 78 (89.7) | |

| T4 | 5 (5.7) | 6 (6.9) | |

| Clinical N stage | 0.875 | ||

| N0 | 28 (32.2) | 25 (28.7) | |

| N1 | 31 (35.6) | 29 (33.3) | |

| N2 | 25 (28.7) | 30 (34.5) | |

| N3 | 3 (3.4) | 3 (3.4) | |

| Clinical stage | 0.933 | ||

| II | 30 (34.5) | 28 (32.2) | |

| III | 49 (56.3) | 50 (57.5) | |

| IV | 8 (9.2) | 9 (10.3) |

| n (%) | nCRT (n = 87) | nCIT (n = 87) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| PR/CR | <0.001 | ||

| yes | 74 (85.1) | 40 (46.0) | |

| no | 13 (14.9) | 47 (54.0) | |

| pCR | <0.001 | ||

| yes | 33 (37.9) | 13 (14.9) | |

| no | 54 (62.1) | 74 (85.1) | |

| MPR | 0.034 | ||

| yes | 51 (58.6) | 37 (42.5) | |

| no | 36 (41.4) | 50 (57.5) | |

| Postoperative T stage descending | 0.006 | ||

| yes | 68 (78.2) | 51 (58.6) | |

| no | 19 (21.8) | 36 (41.4) | |

| Postoperative N stage descending | <0.001 | ||

| yes | 74 (85.1) | 40 (46.0) | |

| no | 13 (14.9) | 47 (54.0) |

| nCIT (%, n/N) | nCRT (%, n/N) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1-year DFS | 91.72% (80/87) | 76.55% (67/87) |

| 2-year DFS | 76.73% (67/87) | 55.09% (48/87) |

| 3-year DFS | 66.35% (58/87) | 47.32% (41/87) |

| 1-year OS | 96.43% (84/87) | 88.27% (77/87) |

| 2-year OS | 82.49% (72/87) | 68.03% (59/87) |

| 3-year OS | 75.89% (66/87) | 55.57% (48/87) |

| TRAEs n (%) | nCRT (n = 87) | nCIT (n = 87) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myelosuppression | 0.839 | ||

| Grade 1/2 | 73 (83.9) | 72 (82.8) | |

| Grade ≥ 3 | 14 (16.1) | 15 (17.2) | |

| Liver dysfunction | 0.497 | ||

| Grade 1/2 | 85 (97.7) | 87 (1) | |

| Grade ≥ 3 | 2 (2.3) | 0 | |

| Vomiting | 0.278 | ||

| Grade 1/2 | 81 (93.1) | 85 (97.7) | |

| Grade ≥ 3 | 6 (6.9) | 2 (2.3) | |

| Pneumonia | 0.070 | ||

| yes | 32 (36.8) | 21 (24.1) | |

| no | 55 (63.2) | 66 (75.9) | |

| Esophageal fistula | 0.621 | ||

| yes | 1 (1.1) | 3 (3.4) | |

| no | 86 (98.9) | 84 (96.6) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Deng, S.; Yan, X.; Peng, Y.; Zhu, L.; Shen, Y.; Ying, W.; Xu, Y.; Fu, Z. Three-Year Outcomes of Neoadjuvant Chemoimmunotherapy vs. Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy in Resectable Esophageal Cancer: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. Cancers 2026, 18, 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010155

Deng S, Yan X, Peng Y, Zhu L, Shen Y, Ying W, Xu Y, Fu Z. Three-Year Outcomes of Neoadjuvant Chemoimmunotherapy vs. Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy in Resectable Esophageal Cancer: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):155. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010155

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeng, Shilong, Xue Yan, Ying Peng, Lijun Zhu, Yongshi Shen, Wenmin Ying, Yuanji Xu, and Zhichao Fu. 2026. "Three-Year Outcomes of Neoadjuvant Chemoimmunotherapy vs. Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy in Resectable Esophageal Cancer: A Multicenter Retrospective Study" Cancers 18, no. 1: 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010155

APA StyleDeng, S., Yan, X., Peng, Y., Zhu, L., Shen, Y., Ying, W., Xu, Y., & Fu, Z. (2026). Three-Year Outcomes of Neoadjuvant Chemoimmunotherapy vs. Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy in Resectable Esophageal Cancer: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. Cancers, 18(1), 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010155