Circulating Tumor Cells in Glioblastoma

Simple Summary

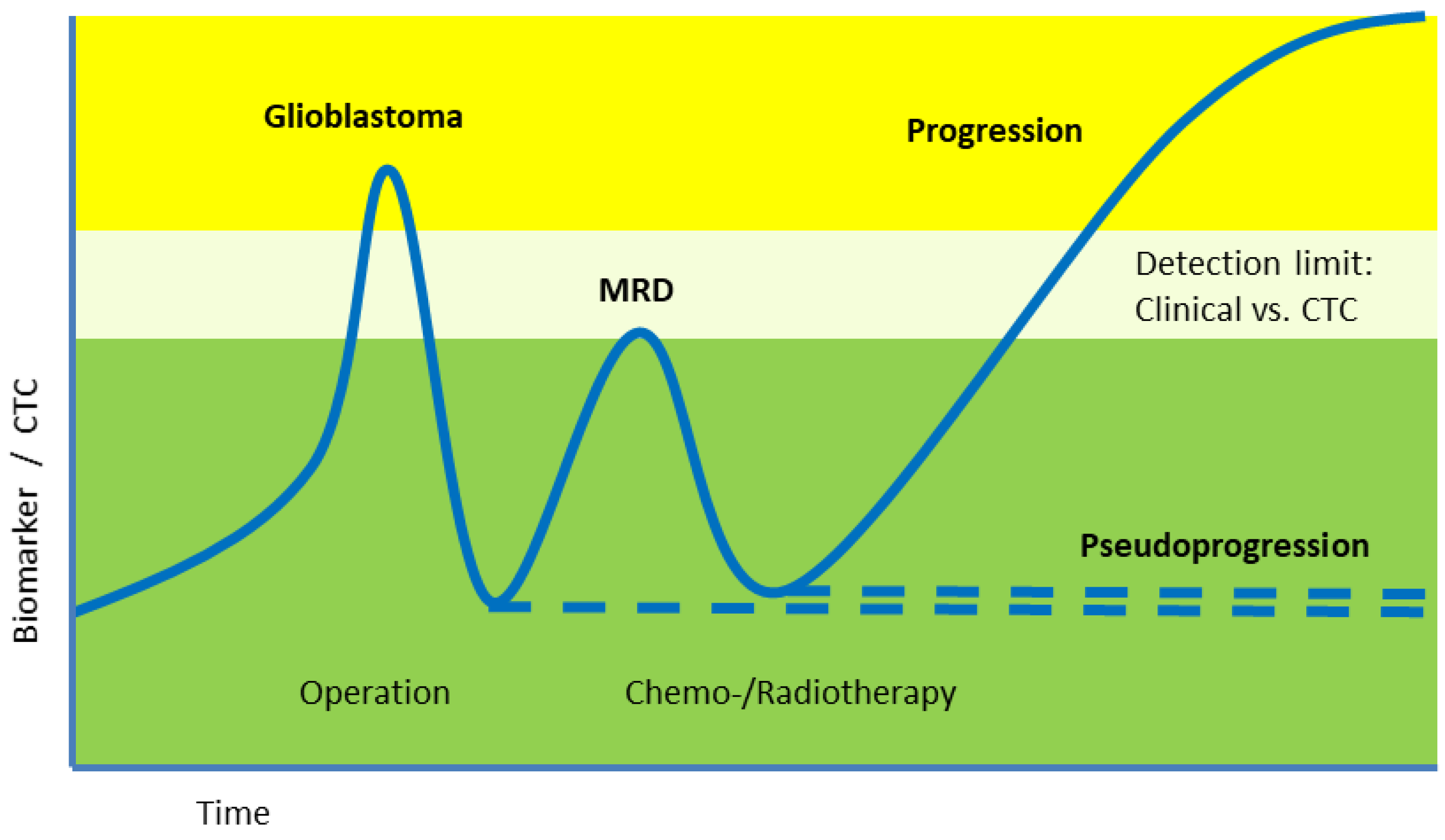

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs)

3. Comparative Perspective on Liquid Biopsy Modalities in Glioblastoma

4. Isolation, Enrichment, Characterization

5. Limitations and Current Barriers

6. Glioblastoma vs. Extracranial Tumors

6.1. Extracranial Tumors

6.2. Glioblastoma

6.3. Clinical Studies

7. Challenges

8. Conclusions

9. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ohgaki, H.; Kleihues, P. Genetic Pathways to Primary and Secondary Glioblastoma. Am. J. Pathol. 2007, 170, 1445–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Cioffi, G.; Waite, K.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2014–2018. Neuro-Oncology 2021, 23, iii1–iii105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.P.; Nahed, B.V.; Madden, M.W.; Oliveira, S.M.; Springer, S.; Bhere, D.; Chi, A.S.; Wakimoto, H.; Rothenberg, S.M.; Sequist, L.V.; et al. Brain tumor cells in circulation are enriched for mesenchymal gene expression. Cancer Discov. 2014, 4, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, P.; Cushing, H. A Classification of the Tumours of the Glioma Group on a Histogenetic Basis, with a Correlated Study of Prognosis; J. B. Lippincott Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA; London, UK; Montreal, QC, Canada, 1926; p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Wesseling, P.; Brat, D.J.; Cree, I.A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Hawkins, C.; Ng, H.K.; Pfister, S.M.; Reifenberger, G.; et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A summary. Neuro-Oncology 2021, 23, 1231–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldape, K.; Zadeh, G.; Mansouri, S.; Reifenberger, G.; von Deimling, A. Glioblastoma: Pathology, molecular mechanisms and markers. Acta Neuropathol. 2015, 129, 829–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, C.; Holtschmidt, J.; Auer, M.; Heitzer, E.; Lamszus, K.; Schulte, A.; Matschke, J.; Langer-Freitag, S.; Gasch, C.; Stoupiec, M.; et al. Hematogenous dissemination of glioblastoma multiforme. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 247ra101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perryman, L.; Erler, J.T. Brain cancer spreads. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 247fs228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccelli, I.; Schneeweiss, A.; Riethdorf, S.; Stenzinger, A.; Schillert, A.; Vogel, V.; Klein, C.; Saini, M.; Bauerle, T.; Wallwiener, M.; et al. Identification of a population of blood circulating tumor cells from breast cancer patients that initiates metastasis in a xenograft assay. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eibl, R.H.; Schneemann, M. Liquid Biopsy and Cancer. In Cancer Treatment Modalities: An Interdisciplinary Approach; Rezaei, N., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 367–391. [Google Scholar]

- Eibl, R.H.; Schneemann, M. Cell-free DNA as a biomarker in cancer. Extracell. Vesicles Circ. Nucleic Acids 2022, 3, 178–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eibl, R.H.; Schneemann, M. Liquid biopsy and glioblastoma. Explor. Target. Anti-Tumor Ther. 2023, 4, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Ricarte, F.; Mayor, R.; Martínez-Sáez, E.; Rubio-Pérez, C.; Pineda, E.; Cordero, E.; Cicuéndez, M.; Poca, M.A.; López-Bigas, N.; Cajal, S.R.Y.; et al. Molecular Diagnosis of Diffuse Gliomas through Sequencing of Cell-Free Circulating Tumor DNA from Cerebrospinal Fluid. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 2812–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.M.; Shah, R.H.; Pentsova, E.I.; Pourmaleki, M.; Briggs, S.; Distefano, N.; Zheng, Y.; Skakodub, A.; Mehta, S.A.; Campos, C.; et al. Tracking tumour evolution in glioma through liquid biopsies of cerebrospinal fluid. Nature 2019, 565, 654–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouliere, F.; Mair, R.; Chandrananda, D.; Marass, F.; Smith, C.G.; Su, J.; Morris, J.; Watts, C.; Brindle, K.M.; Rosenfeld, N. Detection of cell-free DNA fragmentation and copy number alterations in cerebrospinal fluid from glioma patients. EMBO Mol. Med. 2018, 10, e9323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Long, W.; Liu, Q. Current Advances and Future Perspectives of Cerebrospinal Fluid Biopsy in Midline Brain Malignancies. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2019, 20, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Springer, S.; Zhang, M.; McMahon, K.W.; Kinde, I.; Dobbyn, L.; Ptak, J.; Brem, H.; Chaichana, K.; Gallia, G.L.; et al. Detection of tumor-derived DNA in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with primary tumors of the brain and spinal cord. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 9704–9709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Mattos-Arruda, L.; Mayor, R.; Ng, C.K.Y.; Weigelt, B.; Martínez-Ricarte, F.; Torrejon, D.; Oliveira, M.; Arias, A.; Raventos, C.; Tang, J.; et al. Cerebrospinal fluid-derived circulating tumour DNA better represents the genomic alterations of brain tumours than plasma. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majchrzak-Celińska, A.; Paluszczak, J.; Kleszcz, R.; Magiera, M.; Barciszewska, A.-M.; Nowak, S.; Baer-Dubowska, W. Detection of MGMT, RASSF1A, p15INK4B, and p14ARF promoter methylation in circulating tumor-derived DNA of central nervous system cancer patients. J. Appl. Genet. 2013, 54, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, T.R. A case of cancer in which cells similar to those in the tumours were seen in the blood after death. Aust. Med. J. 1869, 14, 146–147. [Google Scholar]

- Paget, S. The distribution of secondary growths in cancer of the breast. Lancet 1889, 133, 571–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidler, I.J. Biological behavior of malignant melanoma cells correlated to their survival in vivo. Cancer Res. 1975, 35, 218–224. [Google Scholar]

- Eibl, R.H.; Pietsch, T.; Moll, J.; Skroch-Angel, P.; Heider, K.H.; von Ammon, K.; Wiestler, O.D.; Ponta, H.; Kleihues, P.; Herrlich, P. Expression of variant CD44 epitopes in human astrocytic brain tumors. J. Neuro-Oncol. 1995, 26, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reya, T.; Morrison, S.J.; Clarke, M.F.; Weissman, I.L. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature 2001, 414, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, W.J.; Matera, J.; Miller, M.C.; Repollet, M.; Connelly, M.C.; Rao, C.; Tibbe, A.G.J.; Uhr, J.W.; Terstappen, L.W.M.M. Tumor Cells Circulate in the Peripheral Blood of All Major Carcinomas but not in Healthy Subjects or Patients with Nonmalignant Diseases. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 6897–6904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristofanilli, M.; Budd, G.T.; Ellis, M.J.; Stopeck, A.; Matera, J.; Miller, M.C.; Reuben, J.M.; Doyle, G.V.; Allard, W.J.; Terstappen, L.W.M.M.; et al. Circulating Tumor Cells, Disease Progression, and Survival in Metastatic Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maheswaran, S.; Sequist, L.V.; Nagrath, S.; Ulkus, L.; Brannigan, B.; Collura, C.V.; Inserra, E.; Diederichs, S.; Iafrate, A.J.; Bell, D.W.; et al. Detection of mutations in EGFR in circulating lung-cancer cells. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.J.; Punt, C.J.A.; Iannotti, N.; Saidman, B.H.; Sabbath, K.D.; Gabrail, N.Y.; Picus, J.; Morse, M.; Mitchell, E.; Miller, M.C.; et al. Relationship of circulating tumor cells to tumor response, progression-free survival, and overall survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 3213–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bono, J.S.; Scher, H.I.; Montgomery, R.B.; Parker, C.; Miller, M.C.; Tissing, H.; Doyle, G.V.; Terstappen, L.W.W.M.; Pienta, K.J.; Raghavan, D. Circulating Tumor Cells Predict Survival Benefit from Treatment in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 6302–6309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantel, K.; Alix-Panabières, C. Circulating tumour cells in cancer patients: Challenges and perspectives. Trends Mol. Med. 2010, 16, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, S.-J.; Tsui, D.W.Y.; Murtaza, M.; Biggs, H.; Rueda, O.M.; Chin, S.-F.; Dunning, M.J.; Gale, D.; Forshew, T.; Mahler-Araujo, B.; et al. Analysis of Circulating Tumor DNA to Monitor Metastatic Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1199–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, R.P.L.; Ammerlaan, W.; Andree, K.C.; Bender, S.; Cayrefourcq, L.; Driemel, C.; Koch, C.; Luetke-Eversloh, M.V.; Oulhen, M.; Rossi, E.; et al. Proficiency Testing to Assess Technical Performance for CTC-Processing and Detection Methods in CANCER-ID. Clin. Chem. 2021, 67, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polzer, B.; Medoro, G.; Pasch, S.; Fontana, F.; Zorzino, L.; Pestka, A.; Andergassen, U.; Meier-Stiegen, F.; Czyz, Z.T.; Alberter, B.; et al. Molecular profiling of single circulating tumor cells with diagnostic intention. EMBO Mol. Med. 2014, 6, 1371–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazel, M.; Jacot, W.; Pantel, K.; Bartkowiak, K.; Topart, D.; Cayrefourcq, L.; Rossille, D.; Maudelonde, T.; Fest, T.; Alix-Panabières, C. Frequent expression of PD-L1 on circulating breast cancer cells. Mol. Oncol. 2015, 9, 1773–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krol, I.; Castro-Giner, F.; Maurer, M.; Gkountela, S.; Szczerba, B.M.; Scherrer, R.; Coleman, N.; Carreira, S.; Bachmann, F.; Anderson, S.; et al. Detection of circulating tumour cell clusters in human glioblastoma. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 119, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczerba, B.M.; Castro-Giner, F.; Vetter, M.; Krol, I.; Gkountela, S.; Landin, J.; Scheidmann, M.C.; Donato, C.; Scherrer, R.; Singer, J.; et al. Neutrophils escort circulating tumour cells to enable cell cycle progression. Nature 2019, 566, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkountela, S.; Castro-Giner, F.; Szczerba, B.M.; Vetter, M.; Landin, J.; Scherrer, R.; Krol, I.; Scheidmann, M.C.; Beisel, C.; Stirnimann, C.U.; et al. Circulating Tumor Cell Clustering Shapes DNA Methylation to Enable Metastasis Seeding. Cell 2019, 176, 98–112.e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, T.; Cressiot, B.; Parisi, C.; Smolyakov, G.; Thiébot, B.; Trichet, L.; Fernandes, F.M.; Pelta, J.; Manivet, P. Circulating Tumor Cells in Cancer Diagnostics and Prognostics by Single-Molecule and Single-Cell Characterization. ACS Sens. 2023, 8, 406–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eibl, R.H.; Schneemann, M. Liquid Biopsy and Primary Brain Tumors. Cancers 2021, 13, 5429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantel, K.; Alix-Panabières, C. The clinical significance of circulating tumor cells. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 4, 62–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, C.S.; Mishra, A.; Edd, J.; Toner, M.; Maheswaran, S.; Haber, D.A. Circulating tumor cells: Blood-based detection, molecular biology, and clinical applications. Cancer Cell 2025, 43, 1399–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkumur, E.; Shah, A.M.; Ciciliano, J.C.; Emmink, B.L.; Miyamoto, D.T.; Brachtel, E.; Yu, M.; Chen, P.I.; Morgan, B.; Trautwein, J.; et al. Inertial focusing for tumor antigen-dependent and -independent sorting of rare circulating tumor cells. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 179ra147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, C.S.; Foerch, C.; Schänzer, A.; Heck, A.; Plate, K.H.; Seifert, V.; Steinmetz, H.; Raabe, A.; Sitzer, M. Serum GFAP is a diagnostic marker for glioblastoma multiforme. Brain 2007, 130, 3336–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Cui, Y.; Jiang, H.; Sui, D.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Lin, S. Circulating tumor cell is a common property of brain glioma and promotes the monitoring system. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 71330–71340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preuss, I.; Eberhagen, I.; Haas, S.; Eibl, R.H.; Kaufmann, M.; von Minckwitz, G.; Kaina, B. O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase activity in breast and brain tumors. Int. J. Cancer 1995, 61, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, D. Tracking Cancer in Liquid Biopsies. 2020. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d42859-020-00070-z (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Eibl, R.H.; Kleihues, P.; Jat, P.S.; Wiestler, O.D. A model for primitive neuroectodermal tumors in transgenic neural transplants harboring the SV40 large T antigen. Am. J. Pathol. 1994, 144, 556–564. [Google Scholar]

- Muller Bark, J.; Kulasinghe, A.; Hartel, G.; Leo, P.; Warkiani, M.E.; Jeffree, R.L.; Chua, B.; Day, B.W.; Punyadeera, C. Isolation of Circulating Tumour Cells in Patients with Glioblastoma Using Spiral Microfluidic Technology—A Pilot Study. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 681130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessi, F.; Morelli, M.; Franceschi, S.; Aretini, P.; Menicagli, M.; Marranci, A.; Pasqualetti, F.; Gambacciani, C.; Pieri, F.; Grimod, G.; et al. Innovative Approach to Isolate and Characterize Glioblastoma Circulating Tumor Cells and Correlation with Tumor Mutational Status. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Xu, H.; Huang, M.; Ma, W.; Saxena, D.; Lustig, R.A.; Alonso-Basanta, M.; Zhang, Z.; O’Rourke, D.M.; Zhang, L.; et al. Circulating Glioma Cells Exhibit Stem Cell-like Properties. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 6632–6642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvedilol with Chemotherapy in Second Line Glioblastoma and Response of Circulating Tumor Cells [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): U.S.A. National Library of Medicine. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03861598 (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Liquid Biopsy in Low-Grade Glioma Patients (GLIOLIPSY) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): U.S.A. National Library of Medicine. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05133154 (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Aslan, K.; Turco, V.; Blobner, J.; Sonner, J.K.; Liuzzi, A.R.; Núñez, N.G.; De Feo, D.; Kickingereder, P.; Fischer, M.; Green, E.; et al. Heterogeneity of response to immune checkpoint blockade in hypermutated experimental gliomas. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chih, Y.C.; Dietsch, A.C.; Koopmann, P.; Ma, X.; Agardy, D.A.; Zhao, B.; De Roia, A.; Kourtesakis, A.; Kilian, M.; Kramer, C.; et al. Vaccine-induced T cell receptor T cell therapy targeting a glioblastoma stemness antigen. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiestler, O.D.; Brüstle, O.; Eibl, R.H.; Radner, H.; Von Deimling, A.; Plate, K.; Aguzzi, A.; Kleihues, P. A new approach to the molecular basis of neoplastic transformation in the brain. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 1992, 18, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plodinec, M.; Loparic, M.; Monnier, C.A.; Obermann, E.C.; Zanetti-Dallenbach, R.; Oertle, P.; Hyotyla, J.T.; Aebi, U.; Bentires-Alj, M.; Lim, R.Y.; et al. The nanomechanical signature of breast cancer. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012, 7, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, R.; Qi, X.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, L.; Li, M. High-throughput atomic force microscopy measurements reveal mechanical signatures of cell mixtures for liquid biopsy. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 28195–28208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eibl, R.H.; Benoit, M. Molecular resolution of cell adhesion forces. IEE Proc. Nanobiotechnol. 2004, 151, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eibl, R.H.; Moy, V.T. Atomic force microscopy measurements of protein-ligand interactions on living cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2005, 305, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eibl, R.H. Single-Molecule Studies of Integrins by AFM-Based Force Spectroscopy on Living Cells. In Scanning Probe Microscopy in Nanoscience and Nanotechnology 3; Bhushan, B., Ed.; NanoScience and Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 137–169. [Google Scholar]

- Riva, M.; Sciortino, T.; Secoli, R.; D’Amico, E.; Moccia, S.; Fernandes, B.; Conti Nibali, M.; Gay, L.; Rossi, M.; De Momi, E.; et al. Glioma biopsies Classification Using Raman Spectroscopy and Machine Learning Models on Fresh Tissue Samples. Cancers 2021, 13, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe, J.C.; Wang, Z.; Huang, S. Unveiling brain disorders using liquid biopsy and Raman spectroscopy. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 11879–11913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Li, J.; Pan, J.; Wu, N.; Xu, Q.; Zhou, Q.Q.; Wang, Q.; Han, D.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Q.; et al. Precise Identification of Glioblastoma Micro-Infiltration at Cellular Resolution by Raman Spectroscopy. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2401014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe, J.C.; Wang, Z.; Huang, S. Raman Spectroscopy on Brain Disorders: Transition from Fundamental Research to Clinical Applications. Biosensors 2022, 13, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pax, M.; Rieger, J.; Eibl, R.H.; Thielemann, C.; Johannsmann, D. Measurements of fast fluctuations of viscoelastic properties with the quartz crystal microbalance. Analyst 2005, 130, 1474–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Beltran, A.N.; Masuzzo, P.; Ampe, C.; Bakker, G.-J.; Besson, S.; Eibl, R.H.; Friedl, P.; Gunzer, M.; Kittisopikul, M.; Dévédec, S.E.L.; et al. Community standards for open cell migration data. Gigascience 2020, 9, giaa041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Author(s) | Method | Tumor Type | Milestone |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1869 | Ashworth T.R. [20] | Autopsy; microscopy; case report | Unknown primary tumor | First description of tumor cells in blood; morphologically identical to metastatic lesions |

| 1889 | Paget S. [21] | Autopsy | Breast cancer | Formulation of the ‘seed and soil’ hypothesis of metastasis |

| 1975 | Fidler I.J. [22] | Experimental metastasis assay | B16 melanoma | Only a small fraction of injected tumor cells forms metastases |

| 1995 | Eibl R.H. et al. [23] | Molecular and functional characterization | Glioblastoma and astrocytoma | First detection of CD44 splice variants; potential CTC markers |

| 2001 | Reya T. et al. [24] | Stem-cell biology applied to cancer heterogeneity | Solid tumors and leukemia; migratory CSCs | Development of the cancer stem cell concept |

| 2004 | Allard W.J. et al. [25] | CellSearch™ | Prostate, breast, ovarian, CRC, lung cancers | CTC detection in 7.5 mL blood samples |

| 2004 | Cristofanilli M. et al. [26] | CellSearch™ (CTC enumeration) | Metastatic breast cancer | CTCs as independent predictor of reduced PFS and OS |

| 2008 | Maheswaran S. et al. [27] | Molecular profiling; EGFR mutation detection | NSCLC | CTC-based therapy monitoring |

| 2008 | Cohen S.J. et al. [28] | CellSearch™; clinical study | Colorectal cancer | Clinical feasibility of CTC enumeration |

| 2008 | De Bono J.S. et al. [29] | Clinical study | Prostate cancer | CTC count as strongest independent predictor of OS |

| 2010 | Pantel K., Alix-Panabières C. [30] | Conceptual review | Metastatic cancers | Introduction of the term ‘liquid biopsy’ |

| 2013 | Dawson S.J. et al. [31] | Disease monitoring | Breast cancer | ctDNA more sensitive than CTCs for therapy monitoring |

| 2013 | Baccelli et al. [9] | Xenograft | Breast cancer | Identification of metastasis-initiating CTC subsets |

| 2014 | Sullivan J.P. et al. [3] | CTC-iChip (negative depletion) | GBM | Demonstration of CTCs in glioblastoma |

| 2014 | Neves R.P. et al. [32] | Microfluidic enrichment | NSCLC | EGFR variant detection via single-cell sequencing |

| 2014 | Polzer B. et al. [33] | CTC genome/transcriptome profiling | Breast cancer | Diagnostic potential; heterogeneity to primary tumors |

| 2015 | Mazel M. et al. [34] | CellSearch™ | Breast cancer | PD-L1 detection on CTCs |

| 2018 | Krol et al. [35] | — | GBM | Identification of CTC clusters in blood |

| 2019 | Szczerba P. et al. [36] | CTC analysis | GBM | Neutrophils escort CTCs; support proliferation and metastasis |

| 2019 | Gkountela S. et al. [37] | CTC analysis | GBM | CTC clusters show distinct methylation and higher metastatic potential |

| 2023 | Chowdhury et al. [38] | Advanced CTC detection; single-cell profiling | Various cancers | Technical advances in CTC analysis |

| Pro | Con | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Sufficient sensitivity in some advanced cancers | Limited sensitivity in screening, early-stage cancers, many advanced cancers | Prognostic markers in metastatic breast, prostate, colorectal cancers |

| FDA-approved enumeration for specific applications | Not standardized, experimental methods; centralized high-tech laboratories | Prediction of relapse, incl. treatment response using living CTCs (cell culture, xenograft) |

| High specificity (mutations) | Sophisticated technology, no easy/common standards; expensive; no remuneration; extra challenges for brain tumors (lacking epithelial markers) | Clinical potential; research use; high cost; limited availability |

| Liquid Biopsy | Material | Strengths | Limitations | Clinical Maturity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) | Intact, viable tumor cells | Preserve cellular phenotype; allow functional assays; enable single-cell multi-omics; potential insight into invasion and resistance | Ultra-rare; no standardized markers; EpCAM-negative phenotype in GBM; technical variability; limited validation | Exploratory/research use |

| Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) | Fragmented tumor-derived DNA | High specificity for mutations; increasingly standardized assays; suitable for longitudinal monitoring; CSF often informative | No cellular/functional information; limited sensitivity in plasma for CNS tumors; reflects mainly genomic alterations | Closest to clinical routine |

| Extracellular vesicles (EVs) | Vesicles carrying proteins, RNA, DNA | Relatively stable; reflect active secretion; multi-analyte potential | Heterogeneous populations; tumor attribution can be difficult; limited standardization | Experimental/early translational |

| CSF biomarkers (proteins, ctDNA) | Cell-free molecules in CSF | Higher proximity to CNS tumors; improved sensitivity vs. blood in many settings | Invasive sampling; not suitable for frequent monitoring in all patients | Translational/selective clinical use |

| Method | Principle | Characteristics | Utility for GBM |

|---|---|---|---|

| CellSearch™ | EpCAM-based immunomagnetic selection | FDA-cleared; isolates EpCAM-positive CTCs; cytokeratin/CD45 staining; automated workflow | Not suitable (GBM typically EpCAM-negative) |

| iChip | Microfluidic inertial focusing + immunomagnetic depletion | High-throughput, marker-independent; preserves viability and heterogeneity | Research tool; potential with GBM-specific markers |

| ScreenCell™ | Microfiltration based on cell size (antigen-independent) | Fast, antigen-independent; efficient for heterogeneous viable CTCs | Suitable for EpCAM-negative GBM |

| pluriBead™ | Bead sieving with bound target cells | High purity, gentle isolation; minimal blood contamination | Potentially advantageous for rare GBM CTCs |

| Year | Study | Tumor | Outcome Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | Gao et al. [44] | GBM, other gliomas | CTC incidence |

| 2018 | Liu et al. [50] | GBM | Similarity of GBM CTCs with CSC (in both mice and humans) |

| 2019-21 | NCT03861598 [51] Early phase 1 study (Morgantown, WV, USA) | GBM | Carvedilol added to standard chemotherapy, correlating MRI controls with new RT-PCR test for CTC detection |

| 2021 | Müller-Bark et al. [48] | GBM | CTC number post-surgery correlated with survival |

| 2021-25 | GLIOLIPSY: LIQUID BIOPSY IN Low-grade Glioma Patients NCT05133154 [52] Interventional study (University Hospital, Montpellier) | Low-/High-grade glioma | Pre- and post-surgery detection and characterization of CTC and TEP |

| 2023-27 | INCIPIENT: INtraventricular CARv3-TEAM-E T Cells for PatIENTs With GBM NCT05660369 Phase 1 study (MGH, Boston, MA, USA) | GBM | CAR-T cell study (dose/safety) in glioblastoma with EGFRvIII mutation, incl. CTC analysis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Eibl, R.H.; Schneemann, M. Circulating Tumor Cells in Glioblastoma. Cancers 2026, 18, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010010

Eibl RH, Schneemann M. Circulating Tumor Cells in Glioblastoma. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleEibl, Robert H., and Markus Schneemann. 2026. "Circulating Tumor Cells in Glioblastoma" Cancers 18, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010010

APA StyleEibl, R. H., & Schneemann, M. (2026). Circulating Tumor Cells in Glioblastoma. Cancers, 18(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010010