AI-Powered Histology for Molecular Profiling in Brain Tumors: Toward Smart Diagnostics from Tissue

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework for Machine Learning-Based AI Algorithm for Brain Tumors: Basics in CNNs, Transformers, and Foundation Models

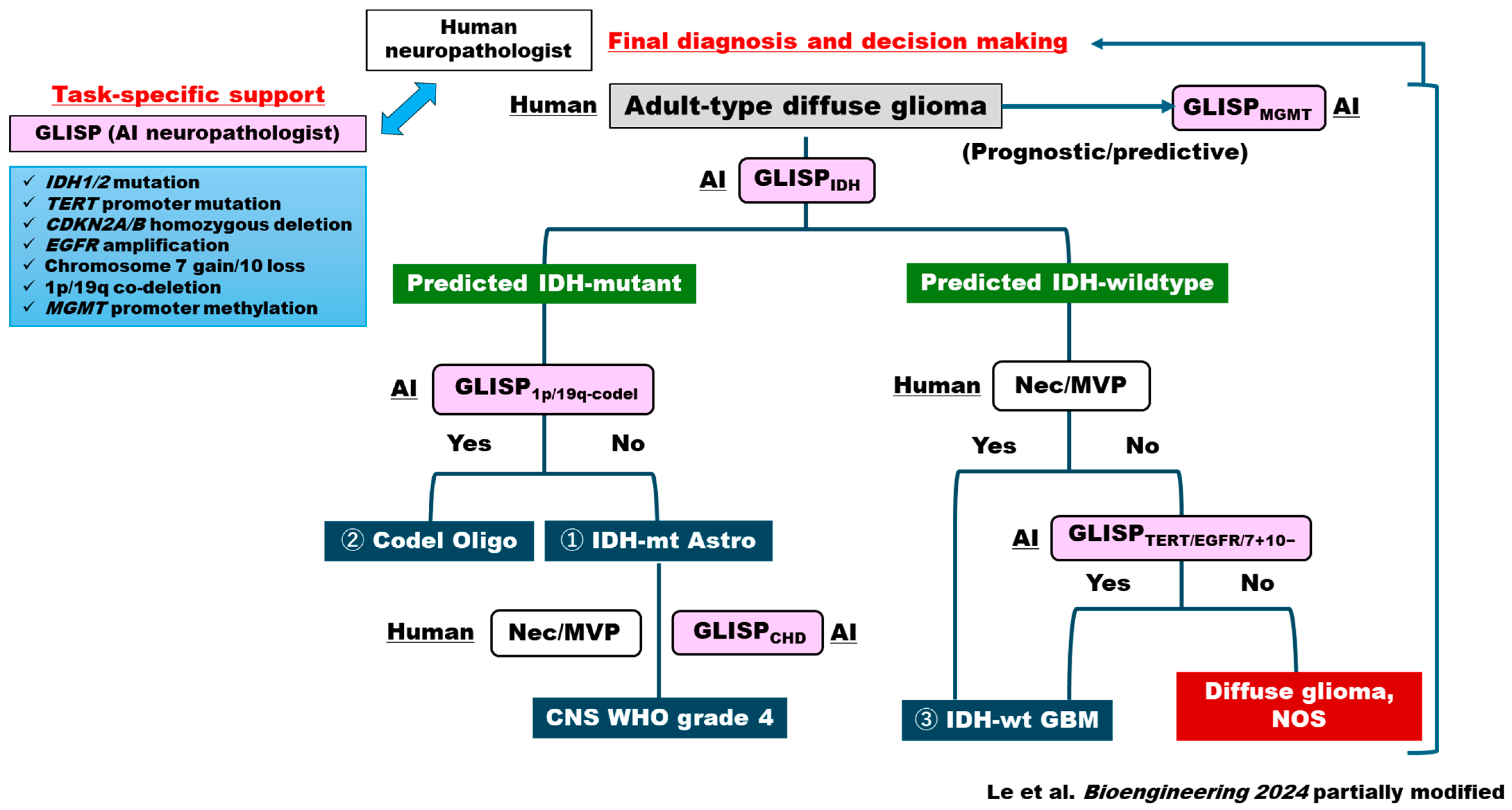

3. Deep Learning in Brain Tumor Histopathology: Updated AI Platform for CNS5-Based Genotype Prediction in Brain Tumors

3.1. AI Diagnostic Algorithm for FFPE-Based Permanent Sections

3.2. AI Diagnostic Algorithm for Intraoperative Frozen Sections

3.3. Deep Learning in Non-Glioma Primary Brain Tumors

4. The Role of Explainable AI in Neuropathology of Brain Tumors: Should AI Be Friendly to Human Neuropathologists?

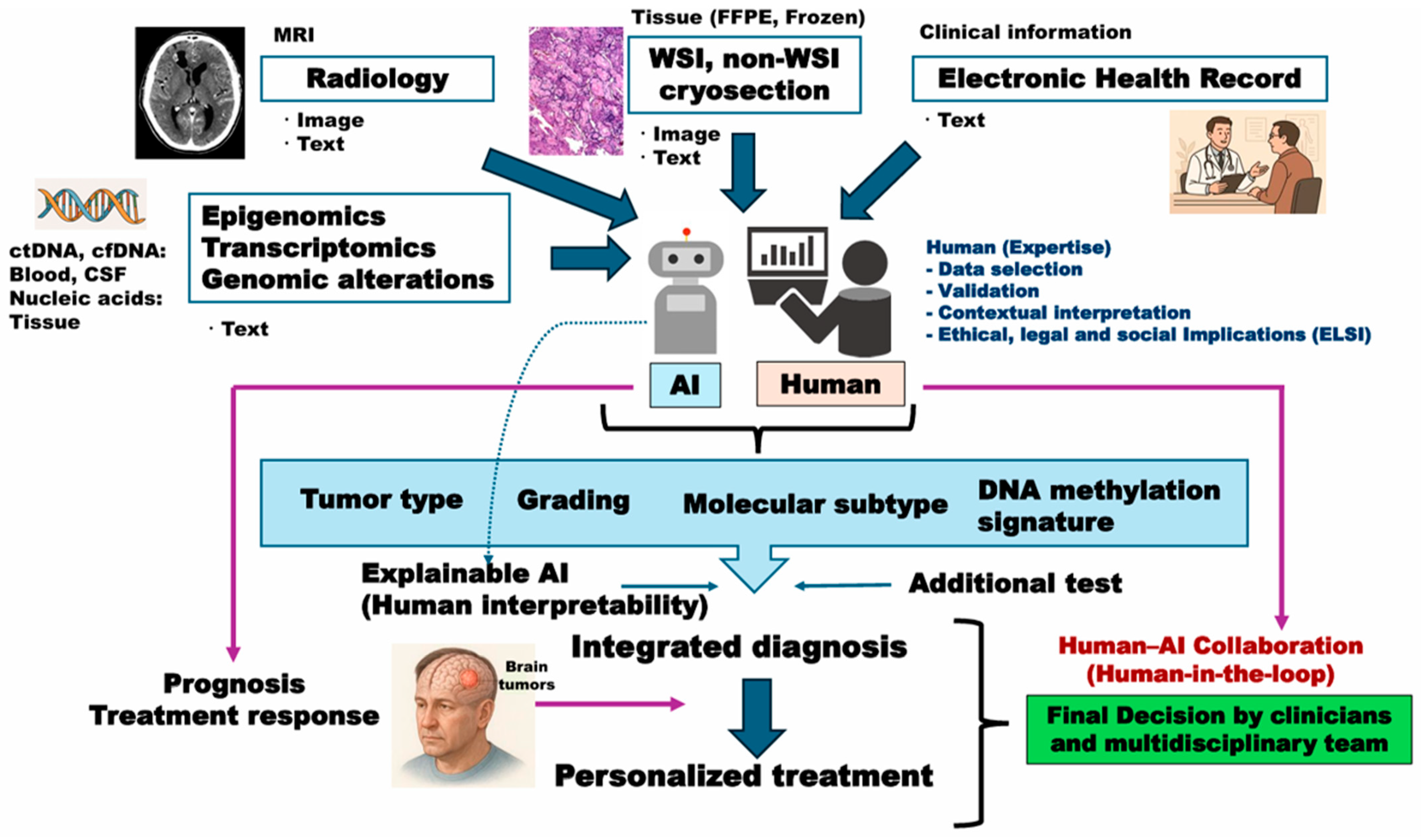

5. Multimodal AI Platform for Integrated Diagnosis of Brain Tumors: Beyond Histo-Genetic Perspectives

6. Issues Under Active Investigation in Clinical Application of AI Models

6.1. H&E Variability

6.2. External Validation

6.3. Digital Imaging Compatibility

6.4. Other Challenges

7. Future Perspectives: Multimodal Collaboration Between Human and AI Neuropathologists

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bera, K.; Schalper, K.A.; Rimm, D.L.; Velcheti, V.; Madabhushi, A. Artificial intelligence in digital pathology—New tools for diagnosis and precision oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 16, 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosravi, P.; Fuchs, T.J.; Ho, D.J. Artificial Intelligence–Driven Cancer Diagnostics: Enhancing Radiology and Pathology through Reproducibility, Explainability, and Multimodality. Cancer Res. 2025, 85, 2356–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalighi, S.; Reddy, K.; Midya, A.; Pandav, K.B.; Madabhushi, A.; Abedalthagafi, M. Artificial intelligence in neuro-oncology: Advances and challenges in brain tumor diagnosis, prognosis, and precision treatment. npj Precis. Oncol. 2024, 8, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jain, A.; Eng, C.; Way, D.H.; Lee, K.; Bui, P.; Kanada, K.; Marinho, G.D.O.; Gallegos, J.; Gabriele, S.; et al. A deep learning system for differential diagnosis of skin diseases. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 900–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteva, A.; Kuprel, B.; Novoa, R.A.; Ko, J.; Swetter, S.M.; Blau, H.M.; Thrun, S. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature 2017, 542, 115–118, Erratum in Nature 2017, 546, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Misawa, M.; Kudo, S.-E. Current Status of Artificial Intelligence Use in Colonoscopy. Digestion 2024, 106, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biffi, C.; Antonelli, G.; Bernhofer, S.; Hassan, C.; Hirata, D.; Iwatate, M.; Maieron, A.; Salvagnini, P.; Cherubini, A. REAL-Colon: A dataset for developing real-world AI applications in colonoscopy. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhate, V.; Castro, L.N.G. Artificial intelligence in neuro-oncology. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1217629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komori, T. AI Neuropathologist: An innovative technology enabling a faultless pathological diagnosis? Neuro-Oncol. 2020, 23, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bent, M.J. Interobserver variation of the histopathological diagnosis in clinical trials on glioma: A clinician’s perspective. Acta Neuropathol. 2010, 120, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Burger, P.; Ellison, D.W.; Reifenberger, G.; von Deimling, A.; Aldape, K.; Brat, D.; Collins, V.P.; Eberhart, C.; et al. International Society of Neuropathology-Haarlem Consensus Guidelines for Nervous System Tumor Classification and Grading. Brain Pathol. 2014, 24, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, D.W.; Jones, S.; Zhang, X.; Lin, J.C.-H.; Leary, R.J.; Angenendt, P.; Mankoo, P.; Carter, H.; Siu, I.-M.; Gallia, G.L.; et al. An Integrated Genomic Analysis of Human Glioblastoma Multiforme. Science 2008, 321, 1807–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, R.B.; Blair, H.; Ballman, K.V.; Giannini, C.; Arusell, R.M.; Law, M.; Flynn, H.; Passe, S.; Felten, S.; Brown, P.D.; et al. A t(1;19)(q10;p10) Mediates the Combined Deletions of 1p and 19q and Predicts a Better Prognosis of Patients with Oligodendroglioma. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 9852–9861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Reifenberger, G.; Von Deimling, A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Cavenee, W.K.; Ohgaki, H.; Wiestler, O.D.; Kleihues, P.; Ellison, D.W. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131, 803–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Wesseling, P.; Brat, D.J.; Cree, I.A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Hawkins, C.; Ng, H.K.; Pfister, S.M.; Reifenberger, G.; et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A summary. Neuro-Oncol. 2021, 23, 1231–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komori, T. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors, 5th edition, central nervous system tumors: The 10 basic principles. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2022, 39, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masui, K.; Mischel, P.S.; Reifenberger, G. Molecular classification of gliomas. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2016, 134, 97–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirahata, M.; Ono, T.; Stichel, D.; Schrimpf, D.; Reuss, D.E.; Sahm, F.; Koelsche, C.; Wefers, A.; Reinhardt, A.; Huang, K.; et al. Novel, improved grading system(s) for IDH-mutant astrocytic gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2018, 136, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masui, K.; Onizuka, H.; Muragaki, Y.; Kawamata, T.; Nagashima, Y.; Kurata, A.; Komori, T. Integrated assessment of malignancy in IDH-mutant astrocytoma with p16 and methylthioadenosine phosphorylase immunohistochemistry. Neuropathology 2024, 45, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brat, D.J.; Aldape, K.; Colman, H.; Holland, E.C.; Louis, D.N.; Jenkins, R.B.; Kleinschmidt-DeMasters, B.K.; Perry, A.; Reifenberger, G.; Stupp, R.; et al. cIMPACT-NOW update 3: Recommended diagnostic criteria for “Diffuse astrocytic glioma, IDH-wildtype, with molecular features of glioblastoma, WHO grade IV”. Acta Neuropathol. 2018, 136, 805–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komori, T. Beyond the WHO 2021 classification of the tumors of the central nervous system: Transitioning from the 5th edition to the next. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2023, 41, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capper, D.; Jones, D.T.W.; Sill, M.; Hovestadt, V.; Schrimpf, D.; Sturm, D.; Koelsche, C.; Sahm, F.; Chavez, L.; Reuss, D.E.; et al. DNA methylation-based classification of central nervous system tumours. Nature 2018, 555, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capper, D.; Stichel, D.; Sahm, F.; Jones, D.T.W.; Schrimpf, D.; Sill, M.; Schmid, S.; Hovestadt, V.; Reuss, D.E.; Koelsche, C.; et al. Practical implementation of DNA methylation and copy-number-based CNS tumor diagnostics: The Heidelberg experience. Acta Neuropathol. 2018, 136, 181–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otani, Y.; Satomi, K.; Suruga, Y.; Ishida, J.; Fujii, K.; Ichimura, K.; Date, I. Utility of genome-wide DNA methylation profiling for pediatric-type diffuse gliomas. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2023, 40, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, L.; Shi, F.; Chun, Q.; Chen, H.; Ma, Y.; Wu, S.; Hameed, N.U.F.; Mei, C.; Lu, J.; Zhang, J.; et al. Artificial intelligence neuropathologist for glioma classification using deep learning on hematoxylin and eosin stained slide images and molecular markers. Neuro-Oncol. 2021, 23, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucchelli, M.; Salzano, S.; Caltabiano, R.; Magro, G.; Certo, F.; Barbagallo, G.; Broggi, G. Diagnostic Performance of ChatGPT-4.0 in Histopathological Analysis of Gliomas: A Single Institution Experience. Neuropathology 2025, 45, e70023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivri, I.; Ozden, F.M.; Gul, G.; Kaygin, E.; Colak, T. Comment on: “Diagnostic Performance of ChatGPT-4.0 in Histopathological Analysis of Gliomas: A Single Institution Experience”. Neuropathology 2025, 45, e70030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Teng, L.; Yan, J.; Guo, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Ji, Y.; Yu, B.; Pei, D.; Duan, W.; et al. Neuropathologist-level integrated classification of adult-type diffuse gliomas using deep learning from whole-slide pathological images. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirae, S.; Debsarkar, S.S.; Kawanaka, H.; Aronow, B.; Prasath, V.B.S. Multimodal Ensemble Fusion Deep Learning Using Histopathological Images and Clinical Data for Glioma Subtype Classification. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 57780–57797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, M.-K.; Kawai, M.; Masui, K.; Komori, T.; Kawamata, T.; Muragaki, Y.; Inoue, T.; Tahara, I.; Kasai, K.; Kondo, T. Glioma Image-Level and Slide-Level Gene Predictor (GLISP) for Molecular Diagnosis and Predicting Genetic Events of Adult Diffuse Glioma. Bioengineering 2024, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sun, T.; Chen, H.; Wu, S.; Cheng, H.; Liu, X.; Lai, Q.; Wang, K.; Chen, L.; Lu, J.; et al. A Multicenter Study on Intraoperative Glioma Grading via Deep Learning on Cryosection Pathology. Mod. Pathol. 2025, 38, 100749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollon, T.; Jiang, C.; Chowdury, A.; Nasir-Moin, M.; Kondepudi, A.; Aabedi, A.; Adapa, A.; Al-Holou, W.; Heth, J.; Sagher, O.; et al. Artificial-intelligence-based molecular classification of diffuse gliomas using rapid, label-free optical imaging. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 828–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orringer, D.A.; Pandian, B.; Niknafs, Y.S.; Hollon, T.C.; Boyle, J.; Lewis, S.; Garrard, M.; Hervey-Jumper, S.L.; Garton, H.J.L.; Maher, C.O.; et al. Rapid intraoperative histology of unprocessed surgical specimens via fibre-laser-based stimulated Raman scattering microscopy. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 1, 0027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollon, T.C.; Pandian, B.; Adapa, A.R.; Urias, E.; Save, A.V.; Khalsa, S.S.S.; Eichberg, D.G.; D’amico, R.S.; Farooq, Z.U.; Lewis, S.; et al. Near real-time intraoperative brain tumor diagnosis using stimulated Raman histology and deep neural networks. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nohman, A.I.; Ivren, M.; Alhalabi, O.T.; Sahm, F.; Trong, P.D.; Krieg, S.M.; Unterberg, A.; Scherer, M. Intraoperative label-free tissue diagnostics using a stimulated Raman histology imaging system with artificial intelligence: An initial experience. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2024, 247, 108646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, C.; Pagès-Gallego, M.; Kester, L.; Kranendonk, M.E.G.; Wesseling, P.; Verburg, N.; Hamer, P.d.W.; Kooi, E.J.; Dankmeijer, L.; van der Lugt, J.; et al. Ultra-fast deep-learned CNS tumour classification during surgery. Nature 2023, 622, 842–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Göbel, K.; Ille, S.; Hinz, F.; Schoebe, N.; Bogumil, H.; Meyer, J.; Brehm, M.; Kardo, H.; Schrimpf, D.; et al. Prospective, multicenter validation of a platform for rapid molecular profiling of central nervous system tumors. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1567–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, S.; Cahyani, I.; Holmes, N.; Fox, G.; Munro, R.; Wibowo, S.; Murray, T.; Mason, H.; Housley, M.; Martin, D.; et al. ROBIN: A unified nanopore-based assay integrating intraoperative methylome classification and next-day comprehensive profiling for ultra-rapid tumor diagnosis. Neuro-Oncol. 2025, 27, 2035–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, D.-T.; Shulman, E.D.; Turakulov, R.; Abdullaev, Z.; Singh, O.; Campagnolo, E.M.; Lalchungnunga, H.; Stone, E.A.; Nasrallah, M.P.; Ruppin, E.; et al. Prediction of DNA methylation-based tumor types from histopathology in central nervous system tumors with deep learning. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 1952–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Carrillo-Perez, F.; Pizurica, M.; Heiland, D.H.; Gevaert, O. Spatial cellular architecture predicts prognosis in glioblastoma. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Shah, Z.; Sav, A.; Russo, C.; Berkovsky, S.; Qian, Y.; Coiera, E.; Di Ieva, A. Isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) status prediction in histopathology images of gliomas using deep learning. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Zanazzi, G.J.; Hassanpour, S. Predicting prognosis and IDH mutation status for patients with lower-grade gliomas using whole slide images. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faust, K.; Lee, M.K.; Dent, A.; Fiala, C.; Portante, A.; Rabindranath, M.; Alsafwani, N.; Gao, A.; Djuric, U.; Diamandis, P. Integrating morphologic and molecular histopathological features through whole slide image registration and deep learning. Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2022, 4, vdac001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Shi, F.; Sun, T.; Chen, H.; Cheng, H.; Liu, X.; Wu, S.; Lu, J.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, J.; et al. Histopathological auxiliary system for brain tumour (HAS-Bt) based on weakly supervised learning using a WHO CNS5-style pipeline. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2023, 163, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, L.; Jones, K.A.; Shboul, Z.A.; Chen, J.Y.; Iftekharuddin, K.M. Deep Neural Network Analysis of Pathology Images with Integrated Molecular Data for Enhanced Glioma Classification and Grading. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 668694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzoubi, I.; Bao, G.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, X.; Graeber, M.B. Artificial intelligence techniques for neuropathological diagnostics and research. Neuropathology 2022, 43, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redlich, J.-P.; Feuerhake, F.; Weis, J.; Schaadt, N.S.; Teuber-Hanselmann, S.; Buck, C.; Luttmann, S.; Eberle, A.; Nikolin, S.; Appenzeller, A.; et al. Applications of artificial intelligence in the analysis of histopathology images of gliomas: A review. npj Imaging 2024, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrallah, M.P.; Zhao, J.; Tsai, C.C.; Meredith, D.; Marostica, E.; Ligon, K.L.; Golden, J.A.; Yu, K.-H. Machine learning for cryosection pathology predicts the 2021 WHO classification of glioma. Med 2023, 4, 526–540.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, R.; Chen, H.; Zheng, X.; Liu, L.; Lan, L.; Li, P.; Wu, S.; Cao, Q.; et al. A multicenter proof-of-concept study on deep learning-based intraoperative discrimination of primary central nervous system lymphoma. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollon, T.; Orringer, D.A. Label-free brain tumor imaging using Raman-based methods. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2021, 151, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pajtler, K.W.; Witt, H.; Sill, M.; Jones, D.T.; Hovestadt, V.; Kratochwil, F.; Wani, K.; Tatevossian, R.; Punchihewa, C.; Johann, P.; et al. Molecular Classification of Ependymal Tumors across All CNS Compartments, Histopathological Grades, and Age Groups. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 728–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, H.; Gramatzki, D.; Hentschel, B.; Pajtler, K.W.; Felsberg, J.; Schackert, G.; Löffler, M.; Capper, D.; Sahm, F.; Sill, M.; et al. DNA methylation-based classification of ependymomas in adulthood: Implications for diagnosis and treatment. Neuro-Oncol. 2018, 20, 1616–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, J.E.; Spohn, M.; Obrecht, D.; Mynarek, M.; Thomas, C.; Hasselblatt, M.; Dorostkar, M.M.; Wefers, A.K.; Frank, S.; Monoranu, C.-M.; et al. Molecular characterization of histopathological ependymoma variants. Acta Neuropathol. 2019, 139, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, Y.; Dottermusch, M.; Schweizer, L.; Krech, M.; Lempertz, T.; Schüller, U.; Neumann, P.; Neumann, J.E. Morphology-based molecular classification of spinal cord ependymomas using deep neural networks. Brain Pathol. 2024, 34, e13239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitney, J.; Dollinger, L.; Tamrazi, B.; Hawes, D.; Couce, M.; Marcheque, J.; Judkins, A.; Margol, A.; Madabhushi, A. Quantitative Nuclear Histomorphometry Predicts Molecular Subtype and Clinical Outcome in Medulloblastomas: Preliminary Findings. J. Pathol. Inform. 2022, 13, 100090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attallah, O. MB-AI-His: Histopathological Diagnosis of Pediatric Medulloblastoma and its Subtypes via AI. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saju, A.C.; Chatterjee, A.; Sahu, A.; Gupta, T.; Krishnatry, R.; Mokal, S.; Sahay, A.; Epari, S.; Prasad, M.; Chinnaswamy, G.; et al. Machine-learning approach to predict molecular subgroups of medulloblastoma using multiparametric MRI-based tumor radiomics. Br. J. Radiol. 2022, 95, 20211359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, K.; Majeed, H.; Irshad, H. Nuclear spatial and spectral features based evolutionary method for meningioma subtypes classification in histopathology. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2017, 80, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessmann, B.; Nattkemper, T.; Hans, V.; Degenhard, A. A method for linking computed image features to histological semantics in neuropathology. J. Biomed. Inform. 2007, 40, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sehring, J.; Dohmen, H.; Selignow, C.; Schmid, K.; Grau, S.; Stein, M.; Uhl, E.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Németh, A.; Amsel, D.; et al. Leveraging Attention-Based Convolutional Neural Networks for Meningioma Classification in Computational Histopathology. Cancers 2023, 15, 5190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirtaheri, P.N.; Akhbari, M.; Najafi, F.; Mehrabi, H.; Babapour, A.; Rahimian, Z.; Rigi, A.; Rahbarbaghbani, S.; Mobaraki, H.; Masoumi, S.; et al. Performance of deep learning models for automatic histopathological grading of meningiomas: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1536751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, M.; Xing, X.; Zheng, L.; Wang, H.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, S.; Yu, T.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Mao, Q.; et al. Weakly supervised deep learning-based classification for histopathology of gliomas: A single center experience. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afonso, M.; Bhawsar, P.M.; Saha, M.; Almeida, J.S.; Oliveira, A.L. Multiple Instance Learning for WSI: A comparative analysis of attention-based approaches. J. Pathol. Inform. 2024, 15, 100403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobadersany, P.; Yousefi, S.; Amgad, M.; Gutman, D.A.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S.; Vega, J.E.V.; Brat, D.J.; Cooper, L.A.D. Predicting cancer outcomes from histology and genomics using convolutional networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E2970–E2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benfatto, S.; Sill, M.; Jones, D.T.W.; Pfister, S.M.; Sahm, F.; von Deimling, A.; Capper, D.; Hovestadt, V. Explainable artificial intelligence of DNA methylation-based brain tumor diagnostics. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, J.; Blasimme, A.; Vayena, E.; Frey, D.; Madai, V.I. Explainability for artificial intelligence in healthcare: A multidisciplinary perspective. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2020, 20, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, N.; Gaw, N.; Singh, P.; Chang, K.; Aggarwal, M.; Chen, B.; Hoebel, K.; Gupta, S.; Patel, J.; Gidwani, M.; et al. Assessing the Trustworthiness of Saliency Maps for Localizing Abnormalities in Medical Imaging. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2021, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uegami, W.; Bychkov, A.; Ozasa, M.; Uehara, K.; Kataoka, K.; Johkoh, T.; Kondoh, Y.; Sakanashi, H.; Fukuoka, J. MIXTURE of human expertise and deep learning—Developing an explainable model for predicting pathological diagnosis and survival in patients with interstitial lung disease. Mod. Pathol. 2022, 35, 1083–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Duan, L.; Dong, G.; Chen, F.; Li, W. Computational pathology-based weakly supervised prediction model for MGMT promoter methylation status in glioblastoma. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1345687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neftel, C.; Laffy, J.; Filbin, M.G.; Hara, T.; Shore, M.E.; Rahme, G.J.; Richman, A.R.; Silverbush, D.; Shaw, M.L.; Hebert, C.M.; et al. An Integrative Model of Cellular States, Plasticity, and Genetics for Glioblastoma. Cell 2019, 178, 835–849.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, V.M.; Will, P.; Kueckelhaus, J.; Sun, N.; Joseph, K.; Salié, H.; Vollmer, L.; Kuliesiute, U.; von Ehr, J.; Benotmane, J.K.; et al. Spatially resolved multi-omics deciphers bidirectional tumor-host interdependence in glioblastoma. Cancer Cell 2022, 40, 639–655.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masui, K.; Mischel, P.S. Metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming in the pathogenesis of glioblastoma: Toward the establishment of “metabolism-based pathology”. Pathol. Int. 2023, 73, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harachi, M.; Masui, K.; Shimizu, E.; Murakami, K.; Onizuka, H.; Muragaki, Y.; Kawamata, T.; Nakayama, H.; Miyata, M.; Komori, T.; et al. DNA hypomethylator phenotype reprograms glutamatergic network in receptor tyrosine kinase gene-mutated glioblastoma. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2024, 12, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyaert, S.; Qiu, Y.L.; Zheng, Y.; Mukherjee, P.; Vogel, H.; Gevaert, O. Multimodal deep learning to predict prognosis in adult and pediatric brain tumors. Commun. Med. 2023, 3, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.J.; Lu, M.Y.; Williamson, D.F.; Chen, T.Y.; Lipkova, J.; Noor, Z.; Shaban, M.; Shady, M.; Williams, M.; Joo, B.; et al. Pan-cancer integrative histology-genomic analysis via multimodal deep learning. Cancer Cell 2022, 40, 865–878.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.; Zhang, J.; Liu, R. Deep learning-based image classification for integrating pathology and radiology in AI-assisted medical imaging. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomaa, A.; Huang, Y.; Hagag, A.; Schmitter, C.; Höfler, D.; Weissmann, T.; Breininger, K.; Schmidt, M.; Stritzelberger, J.; Delev, D.; et al. Comprehensive multimodal deep learning survival prediction enabled by a transformer architecture: A multicenter study in glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2024, 6, vdae122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liechty, B.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Slocum, C.; Bahadir, C.D.; Sabuncu, M.R.; Pisapia, D.J. Machine learning can aid in prediction of IDH mutation from H&E-stained histology slides in infiltrating gliomas. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 22623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, K.J.; Löffler, C.M.L.; Muti, H.S.; Berghoff, A.S.; Eisenlöffel, C.; van Treeck, M.; Carrero, Z.I.; El Nahhas, O.S.M.; Veldhuizen, G.P.; Weil, S.; et al. Direct image to subtype prediction for brain tumors using deep learning. Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2023, 5, vdad139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.J.; Lee, T.; Ahn, S.; Uh, Y.; Kim, S.H. Efficient diagnosis of IDH-mutant gliomas: 1p/19qNET assesses 1p/19q codeletion status using weakly-supervised learning. npj Precis. Oncol. 2023, 7, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanella, G.; Hanna, M.G.; Geneslaw, L.; Miraflor, A.; Silva, V.W.K.; Busam, K.J.; Brogi, E.; Reuter, V.E.; Klimstra, D.S.; Fuchs, T.J. Clinical-grade computational pathology using weakly supervised deep learning on whole slide images. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hezi, H.; Gelber, M.; Balabanov, A.; Maruvka, Y.E.; Freiman, M. CIMIL-CRC: A clinically-informed multiple instance learning framework for patient-level colorectal cancer molecular subtypes classification from H&E stained images. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2024, 259, 108513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.Y.; Chen, B.; Williamson, D.F.K.; Chen, R.J.; Liang, I.; Ding, T.; Jaume, G.; Odintsov, I.; Le, L.P.; Gerber, G.; et al. A visual-language foundation model for computational pathology. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noree, S.; Robles, W.R.Q.; Ko, Y.S.; Yi, M.Y. Leveraging commonality across multiple tissue slices for enhanced whole slide image classification using graph convolutional networks. BMC Med. Imaging 2025, 25, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komura, D.; Ochi, M.; Ishikawa, S. Machine learning methods for histopathological image analysis: Updates in 2024. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 27, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yang, D.M.; Rong, R.; Zhan, X.; Xiao, G. Pathology Image Analysis Using Segmentation Deep Learning Algorithms. Am. J. Pathol. 2019, 189, 1686–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Luo, X.; Wang, G.; Gilmore, H.; Madabhushi, A. A Deep Convolutional Neural Network for segmenting and classifying epithelial and stromal regions in histopathological images. Neurocomputing 2016, 191, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamshad, F.; Khan, S.; Zamir, S.W.; Khan, M.H.; Hayat, M.; Khan, F.S.; Fu, H. Transformers in medical imaging: A survey. Med. Image Anal. 2023, 88, 102802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atabansi, C.C.; Nie, J.; Liu, H.; Song, Q.; Yan, L.; Zhou, X. A survey of Transformer applications for histopathological image analysis: New developments and future directions. Biomed. Eng. Online 2023, 22, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, M.Y.; Chen, B.; Williamson, D.F.K.; Chen, R.J.; Zhao, M.; Chow, A.K.; Ikemura, K.; Kim, A.; Pouli, D.; Patel, A.; et al. A multimodal generative AI copilot for human pathology. Nature 2024, 634, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacking, S. Foundation models in pathology: Bridging AI innovation and clinical practice. J. Clin. Pathol. 2025, 78, 433–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochi, M.; Komura, D.; Ishikawa, S. Pathology Foundation Models. JMA J. 2025, 8, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorontsov, E.; Bozkurt, A.; Casson, A.; Shaikovski, G.; Zelechowski, M.; Severson, K.; Zimmermann, E.; Hall, J.; Tenenholtz, N.; Fusi, N.; et al. A foundation model for clinical-grade computational pathology and rare cancers detection. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2924–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondepudi, A.; Pekmezci, M.; Hou, X.; Scotford, K.; Jiang, C.; Rao, A.; Harake, E.S.; Chowdury, A.; Al-Holou, W.; Wang, L.; et al. Foundation models for fast, label-free detection of glioma infiltration. Nature 2024, 637, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campanella, G.; Chen, S.; Singh, M.; Verma, R.; Muehlstedt, S.; Zeng, J.; Stock, A.; Croken, M.; Veremis, B.; Elmas, A.; et al. A clinical benchmark of public self-supervised pathology foundation models. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bareja, R.; Carrillo-Perez, F.; Zheng, Y.; Pizurica, M.; Nandi, T.N.; Shen, J.; Madduri, R.; Gevaert, O. Evaluating Vision and Pathology Foundation Models for Computational Pathology: A Comprehensive Benchmark Study. medRxiv 2025, 12, 25327250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecclestone, B.R.; Bell, K.; Abbasi, S.; Dinakaran, D.; van Landeghem, F.K.H.; Mackey, J.R.; Fieguth, P.; Reza, P.H. Improving maximal safe brain tumor resection with photoacoustic remote sensing microscopy. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restelli, F.; Pollo, B.; Vetrano, I.G.; Cabras, S.; Broggi, M.; Schiariti, M.; Falco, J.; de Laurentis, C.; Raccuia, G.; Ferroli, P.; et al. Confocal Laser Microscopy in Neurosurgery: State of the Art of Actual Clinical Applications. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remmelink, M.J.; Rip, Y.; Nieuwenhuijzen, J.A.; Ket, J.C.; Oddens, J.R.; de Reijke, T.M.; de Bruin, D.M. Advanced optical imaging techniques for bladder cancer detection and diagnosis: A systematic review. BJU Int. 2024, 134, 890–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, S.C.; Liu, X.; Chan, A.-W.; Denniston, A.K.; Calvert, M.J. Guidelines for clinical trial protocols for interventions involving artificial intelligence: The SPIRIT-AI extension. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1351–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzinger, A.; Langs, G.; Denk, H.; Zatloukal, K.; Müller, H. Causability and explainability of artificial intelligence in medicine. WIREs Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2019, 9, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobel, S.N.; Sultana, S.; Tasir, A.M.; Mridha, M.; Aung, Z. CancerNet: A comprehensive deep learning framework for precise and intelligible cancer identification. Comput. Biol. Med. 2025, 193, 110339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kather, J.N.; Pearson, A.T.; Halama, N.; Jäger, D.; Krause, J.; Loosen, S.H.; Marx, A.; Boor, P.; Tacke, F.; Neumann, U.P.; et al. Deep learning can predict microsatellite instability directly from histology in gastrointestinal cancer. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1054–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drexler, R.; Brembach, F.; Sauvigny, J.; Ricklefs, F.L.; Eckhardt, A.; Bode, H.; Gempt, J.; Lamszus, K.; Westphal, M.; Schüller, U.; et al. Unclassifiable CNS tumors in DNA methylation-based classification: Clinical challenges and prognostic impact. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2024, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Fu, J.; Lu, Z.; Tu, J. Deep learning in integrating spatial transcriptomics with other modalities. Brief. Bioinform. 2024, 26, bbae719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murai, K.; Kobayashi, N.; Tarumi, W.; Nakahata, Y.; Masui, K. Epigenetic dysregulation of high-grade gliomas: From heterogeneity to brain network modulation. Epigenomics 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odate, T.; Lami, K.; Tsuyama, N.; Mori, I.; Kiriyama, Y.; Teramoto, N.; Masuzawa, Y.; Sukhbaatar, O.; Masui, K.; Yoon, H.-S.; et al. Diagnostic challenges of faded hematoxylin and eosin slides: Limitations of re-staining and re-sectioning and possible reason to go digital. Virchows Arch. 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janowczyk, A.; Madabhushi, A. Deep learning for digital pathology image analysis: A comprehensive tutorial with selected use cases. J. Pathol. Inform. 2016, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeffner, F.; Zarella, M.D.; Buchbinder, N.; Bui, M.M.; Goodman, M.R.; Hartman, D.J.; Lujan, G.M.; Molani, M.A.; Parwani, A.V.; Lillard, K.; et al. Introduction to Digital Image Analysis in Whole-slide Imaging: A White Paper from the Digital Pathology Association. J. Pathol. Inform. 2019, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, M.K.K.; Parwani, A.V.; Gurcan, M.N. Digital pathology and artificial intelligence. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, e253–e261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madusanka, N.; Jayalath, P.; Fernando, D.; Yasakethu, L.; Lee, B.-I. Impact of H&E Stain Normalization on Deep Learning Models in Cancer Image Classification: Performance, Complexity, and Trade-Offs. Cancers 2023, 15, 4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, T.; Wang, X.; Hu, D.; Huang, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, F.; Li, G. Stain Normalization of Histopathological Images Based on Deep Learning: A Review. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jose, L.; Liu, S.; Russo, C.; Nadort, A.; Di Ieva, A. Generative Adversarial Networks in Digital Pathology and Histopathological Image Processing: A Review. J. Pathol. Inform. 2021, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madusanka, N.; Padmanabha, P.; Guruge, K.; Lee, B.-I. Structure-Preserving Histopathological Stain Normalization via Attention-Guided Residual Learning. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, J.; Robbins, M.; McNeil, C.; Yoshitake, T.; Santori, C.; Shan, C.; Vyawahare, S.; Patel, H.; Wang, T.C.; Findlater, R.; et al. Autofluorescence Virtual Staining System for H&E Histology and Multiplex Immunofluorescence Applied to Immuno-Oncology Biomarkers in Lung Cancer. Cancer Res. Commun. 2025, 5, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koka, R.; Wake, L.M.; Ku, N.K.; Rice, K.; LaRocque, A.; Vidal, E.G.; Alexanian, S.; Kozikowski, R.; Rivenson, Y.; Kallen, M.E. Assessment of AI-based computational H&E staining versus chemical H&E staining for primary diagnosis in lymphomas: A brief interim report. J. Clin. Pathol. 2024, 78, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, D.F.; Nagpal, K.; Sayres, R.; Foote, D.J.; Wedin, B.D.; Pearce, A.; Cai, C.J.; Winter, S.R.; Symonds, M.; Yatziv, L.; et al. Evaluation of the Use of Combined Artificial Intelligence and Pathologist Assessment to Review and Grade Prostate Biopsies. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2023267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Deng, X.; Xu, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Liu, J.; Huang, B. Artificial Intelligence in Lymphoma Histopathology: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e62851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juarez-Chambi, R.M.; Kut, C.; Rico-Jimenez, J.J.; Chaichana, K.L.; Xi, J.; Campos-Delgado, D.U.; Rodriguez, F.J.; Quinones-Hinojosa, A.; Li, X.; Jo, J.A. AI-Assisted In Situ Detection of Human Glioma Infiltration Using a Novel Computational Method for Optical Coherence Tomography. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 6329–6338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazor, T.; Farhat, K.S.; Trukhanov, P.; Lindsay, J.; Galvin, M.; Mallaber, E.; Paul, M.A.; Hassett, M.J.; Schrag, D.; Cerami, E.; et al. Clinical Trial Notifications Triggered by Artificial Intelligence–Detected Cancer Progression. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e252013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazerooni, A.F.; Khalili, N.; Liu, X.; Haldar, D.; Jiang, Z.; Anwar, S.M.; Albrecht, J.; Adewole, M.; Anazodo, U.; Anderson, H.; et al. The Brain Tumor Segmentation (BraTS) Challenge 2023: Focus on Pediatrics (CBTN-CONNECT-DIPGR-ASNR-MICCAI BraTS-PEDs). arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.17033v7. [Google Scholar]

- The GLASS Consortium; Aldape, K.; Amin, S.B.; Ashley, D.M.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S.; Bates, A.J.; Beroukhim, R.; Bock, C.; Brat, D.J.; Claus, E.B.; et al. Glioma through the looking GLASS: Molecular evolution of diffuse gliomas and the Glioma Longitudinal Analysis Consortium. Neuro-Oncol. 2018, 20, 873–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantanowitz, L.; Sharma, A.; Carter, A.B.; Kurc, T.; Sussman, A.; Saltz, J. Twenty Years of Digital Pathology: An Overview of the Road Travelled, What is on the Horizon, and the Emergence of Vendor-Neutral Archives. J. Pathol. Inform. 2018, 9, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Chubb, L.; Pantanowitz, L.; Parwani, A. Standardization in digital pathology: Supplement 145 of the DICOM standards. J. Pathol. Inform. 2011, 2, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clunie, D.; Hosseinzadeh, D.; Wintell, M.; De Mena, D.; Lajara, N.; García-Rojo, M.; Bueno, G.; Saligrama, K.; Stearrett, A.; Toomey, D.; et al. Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine Whole Slide Imaging Connectathon at Digital Pathology Association Pathology Visions 2017. J. Pathol. Inform. 2018, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kameyama, J.; Kodera, S.; Inoue, Y. Ethical, legal, and social issues (ELSI) and reporting guidelines of AI research in healthcare. PLoS Digit. Heal. 2024, 3, e0000607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seoni, S.; Jahmunah, V.; Salvi, M.; Barua, P.D.; Molinari, F.; Acharya, U.R. Application of uncertainty quantification to artificial intelligence in healthcare: A review of last decade (2013–2023). Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 165, 107441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, F.X.; Wolf, S.M.; Lawrenz, F.; Comeau, D.S.; Evans, B.J.; Fair, D.; Farah, M.J.; Garwood, M.; Han, S.D.; Illes, J.; et al. Conducting Research with Highly Portable MRI in Community Settings: A Practical Guide to Navigating Ethical Issues and ELSI Checklist. J. Law Med. Ethic 2024, 52, 769–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köy, Y.; Ceylan, O.; Kahraman, A.; Cangi, S.; Özmen, S.; Tihan, T. A retrospective analysis of practical benefits and caveats of the new WHO 2021 central nervous system tumor classification scheme in low-resource settings: “A perspective from low- and middle-income countries”. Neuropathology 2023, 44, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagahashi, M.; Shimada, Y.; Ichikawa, H.; Kameyama, H.; Takabe, K.; Okuda, S.; Wakai, T. Next generation sequencing-based gene panel tests for the management of solid tumors. Cancer Sci. 2018, 110, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.J.; Lu, M.Y.; Wang, J.; Williamson, D.F.K.; Rodig, S.J.; Lindeman, N.I.; Mahmood, F. Pathomic Fusion: An Integrated Framework for Fusing Histopathology and Genomic Features for Cancer Diagnosis and Prognosis. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2022, 41, 757–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masui, K.; Onizuka, H.; Muragaki, Y.; Kawamata, T.; Kurata, A.; Komori, T. Progression of long-term “untreated” oligodendroglioma cases: Possible contribution of genomic instability. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2025, 42, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, U.; Prasad, G.; Curtis, E.J.; Wong, I.T.; Yan, X.; Zhang, S.; Brückner, L.; Turner, K.; Wiese, J.; Wahl, J.; et al. Accurate Prediction of ecDNA in Interphase Cancer Cells using Deep Neural Networks. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajithkumar, A.; Thomas, J.; Saji, A.M.; Ali, F.; Hasin E.K., H.; Adampulan, H.A.G.; Sarathchand, S. Artificial Intelligence in pathology: Current applications, limitations, and future directions. Ir. J. Med Sci. 2023, 193, 1117–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheller, M.J.; Edwards, B.; Reina, G.A.; Martin, J.; Pati, S.; Kotrotsou, A.; Milchenko, M.; Xu, W.; Marcus, D.; Colen, R.R.; et al. Federated learning in medicine: Facilitating multi-institutional collaborations without sharing patient data. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Guo, Z.; Zhou, F.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, J.; Yan, F.; Cai, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Jin, C.; et al. A generalizable pathology foundation model using a unified knowledge distillation pretraining framework. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Madala, N.S.; Huang, C. Pathway-guided architectures for interpretable AI in biological research. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2025, 27, 4779–4791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmiel, W.; Kwiecień, J.; Motyka, K. Saliency Map and Deep Learning in Binary Classification of Brain Tumours. Sensors 2023, 23, 4543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Sonneck, J.; Nagel, D.; Hasenberg, A.; Gunzer, M.; Shi, Y.; Chen, J. AutoQC-Bench: A diffusion model and benchmark for automatic quality control in high-throughput microscopy. npj Imaging 2025, 3, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.; Hermsen, M.; Lesser, E.; Ravichandar, D.; Kremers, W. Developing image analysis pipelines of whole-slide images: Pre- and post-processing. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2020, 5, e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isensee, F.; Jaeger, P.F.; Kohl, S.A.A.; Petersen, J.; Maier-Hein, K.H. nnU-Net: A self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nat. Methods 2020, 18, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, C.; Rao, S.; Santosh, V.; Al-Hussaini, M.; Park, S.H.; Tihan, T.; Buckland, M.E.; Ng, H.; Komori, T. Resource availability for CNS tumor diagnostics in the Asian Oceanian region: A survey by the Asian Oceanian Society of Neuropathology committee for Adapting Diagnostic Approaches for Practical Taxonomy in Resource-Restrained Regions (AOSNP-ADAPTR). Brain Pathol. 2025, 35, e13329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, J.; Beeche, C.; Shi, Z.; Beale, O.; Rosin, B.; Leader, J.K.; Pu, J. Batch-balanced focal loss: A hybrid solution to class imbalance in deep learning. J. Med. Imaging 2023, 10, 051809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinidhi, C.L.; Kim, S.W.; Chen, F.-D.; Martel, A.L. Self-supervised driven consistency training for annotation efficient histopathology image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 2022, 75, 102256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenpflug, L.A.; Nie, Y.; Sheikhzadeh, F.; Koelzer, V.H. A review on federated learning in computational pathology. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 23, 3938–3945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Representative References |

|---|---|

| Glioma-FFPE/permanent sections | |

| Glioma-frozen/intraoperative sections | |

| Non-glioma primary brain tumors |

|

| Explainable AI models | |

| Multimodal AI models |

| Citation (First Author, Year) | Task/Target | Architecture (Representative) | Dataset & Cohort Size | Protocol (Preproc/Training) | Validation Approach | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liechty, 2022 (Sci Rep) [78] | IDH mutation prediction from H&E WSI | Multi-scale ResNet patch classifiers ensemble + slide aggregation (multi-magnification ensemble) | TCGA + institutional cases; total ≈ 500 slides | WSI tiling at multiple magnifications (2.5×, 10×, 20×); patch CNN training; ensemble across scales; pathologist–model fusion experiments | Train/val/test with external institutional test; comparison with neuropathologists; bootstrapped CIs | ML max AUC ≈ 0.88 (human AUC ≈ 0.90); hybrid human + ML AUC ≈ 0.92 |

| Hewitt, 2023 (Neurooncol Adv) [79] | Direct image → WHO subtyping (IDH/ATRX/1p19q, etc) | Weakly supervised MIL + transformer attention | Multi-center cohorts, N = 2845 patients (multiple tumor types) | Slide-level weak supervision (MIL), patch sampling, stain normalization | External validation across multiple cohorts; held-out test sets | Training AUROCs (IDH 0.95; ATRX 0.90; 1p/19q 0.80); External AUCs: IDH ~0.90, ATRX ~0.79, 1p/19q ~0.87 |

| Kim, 2023 (NPJ Precis Onc) [80] | 1p/19q codeletion (IDH-mutant gliomas) | Weakly-supervised slide-level network “1p/19qNET” (patch CNN + regression head) | Discovery DS N = 288; external IVS (TCGA) N = 385 | Slide tiling, weak labels from NGS/FISH; trained to predict fold-change per arm; explainable heatmaps | Cross-validation on DS; external validation on TCGA | R2 (1p) = 0.589, R2 (19q) = 0.547; AUC (IDH-mutant classifier) DS 0.93, IVS 0.837 |

| Wang, 2023 (Nat Commun) [28] | Integrated WHO-style classification from H&E WSIs (adult diffuse gliomas) | Multi-scale MIL + ResNet encoders; slide-level integrated decision pipeline | Training n = 1362; validation n = 340; internal test n = 289; 2 external test cohorts n = 305 & 328 | Multi-scale patch extraction, MIL pooling, integrated outputs for type/grade/genotype | Internal + two external cohorts (multi-center) | High performance; AUROC > 0.90 for major tumor types and genotype classification; subtype accuracy > 90% |

| Ma, 2023 (J Neurooncol)—HAS-Bt [44] | WHO-CNS5 style multi-task pipeline for histopathologic diagnosis | Pipeline MIL (pMIL) with patch encoder + decision logic | 1038 slides; 1,385,163 patches for training; independent test 268 slides | Patch extraction, pMIL pipeline, built-in decision tree using molecular markers when available | Internal train/val + independent test set | 9-class classification accuracy 0.94 on independent dataset; processing time ~443 s/slide |

| Le (GLISP), 2024 (Bioengineering) [30] | Multi-gene predictors (IDH, ATRX, TP53, TERTp, CDKN2A/B, EGFRamp, 7+/10−, 1p/19q, MGMT) from H&E | Two-stage GLISP: patch-level GLISP-P + slide-level GLISP-W (MIL-like) | TCGA training; external Tokyo Women’s Medical Univ external set n = 108 | Patch CNNs, two-stage aggregation (patch → slide), gene-specific output heads | Cross-validation + external Tokyo Women’s Medical Univ testing | Patch/case AUCs: IDH1/2 ~0.75/0.79; 1p/19q patch/case ~0.73/0.80; overall diagnosis accuracy 0.66 (exceeds human avg 0.62) |

| Hollon et al., 2020 (Nat Med) [34] | Near-real-time intraop diagnosis using Stimulated Raman Histology (SRH) + DL | CNN (“SRH-Net”) trained on SRH tiles; rapid inference pipeline | >2.5 million SRH images aggregated across studies; clinical trials: 278 patients across 3 hospitals | SRH imaging of fresh tissue intraop; CNN tile classifier; slide-level aggregation; prospective real-time pipeline (~150 s) | Prospective trials across hospitals; comparison to frozen section and final diagnosis | Diagnostic accuracy 94.6% (rapid SRH + DL) vs. 93.9% conventional methods; real-time capability |

| Hollon et al., 2023 (Nat Med) [32] | Label-free optical imaging (SRH) → molecular classification of diffuse gliomas | CNN classifier on SRH images; optical image → molecular label pipeline | Single/multi-center SRH datasets; ~150 glioma cases in reported prospective evaluation | SRH acquisition (fresh tissue), CNN training on SRH tiles with molecular labels; per-tile → slide aggregation | Prospective evaluation; clinical intraoperative settings | Reported molecular-class prediction accuracies ~90% in prospective setting |

| Patel et al., 2025 (Nat Med) [37] | Prospective multicenter validation of rapid molecular profiling (Rapid-CNS2) | Integrated nanopore sequencing + methylation classifier (MNP-Flex) + ML methylation classifier | Validation cohort = 301 archival + prospective samples (including 18 intraop) + global classifier validation cohort > 78,000 samples for MNP-Flex | Adaptive sampling nanopore sequencing intraop (real-time methylation + CNV), MNP-Flex classifier trained on multi-platform methylation data | Prospective multicenter validation, intraoperative runs | MNP-Flex: 99.6% accuracy for methylation families; Rapid-CNS2 provides real-time methylation classification within 30 min and full profile within 24 h |

| Hoang et al., 2024 (Nat Med) [39] | Predict DNA methylation–defined CNS tumor types from histopathology (DEPLOY/related) | Deep ensemble: direct model + indirect (predict beta values) + demographic model; combination (DEPLOY) | Internal training n = 1796; external test datasets combined n = 2156; total multi-center > 3900 | Patch CNN encoders; predict methylation beta values then classify; high-confidence filtering | Three independent external test datasets (multicenter) | Overall accuracy 95% and balanced accuracy 91% on high-confidence predictions (ten-class mapping) |

| Deacon et al., 2025 (Neuro Oncol)—ROBIN [38] | Ultra-rapid nanopore assay (ROBIN) integrating intraop methylome classification + next-day profiling | Nanopore signal classifier + methylation ML pipeline | Prospective intraop series: 50 cases (reported) in initial evaluation; larger multicenter described | Rapid library prep + nanopore run; three methylation classifiers operating in pipeline; live classification within minutes | Prospective evaluation (intraop) | Concordance with final integrated diagnosis ≈ 90% in prospective set; turnaround < 2 h for intraop classification |

| Challenge | Key Issues | Proposed Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Limited generalizability | Performance drops across scanners, institutions, and patient populations due to domain shift | |

| Data quality & label noise | Variability, artifacts, and inconsistent annotations reduce model reliability | |

| Small cohorts & class imbalance | Rare tumor subtypes lead to insufficient training data and biased model calibration |

|

| Lack of biological interpretability | Limited clinical trust due to “black-box” predictions without biological rationale | |

| Limited prospective/clinical validation | Most models remain retrospective; few prospective or real-world evaluations exist | |

| Reproducibility & transparency | Limited public code/model reporting reduces trust and regulatory readiness |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sakaguchi, M.; Yoshizawa, A.; Masui, K.; Sakai, T.; Komori, T. AI-Powered Histology for Molecular Profiling in Brain Tumors: Toward Smart Diagnostics from Tissue. Cancers 2026, 18, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010009

Sakaguchi M, Yoshizawa A, Masui K, Sakai T, Komori T. AI-Powered Histology for Molecular Profiling in Brain Tumors: Toward Smart Diagnostics from Tissue. Cancers. 2026; 18(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleSakaguchi, Maki, Akihiko Yoshizawa, Kenta Masui, Tomoya Sakai, and Takashi Komori. 2026. "AI-Powered Histology for Molecular Profiling in Brain Tumors: Toward Smart Diagnostics from Tissue" Cancers 18, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010009

APA StyleSakaguchi, M., Yoshizawa, A., Masui, K., Sakai, T., & Komori, T. (2026). AI-Powered Histology for Molecular Profiling in Brain Tumors: Toward Smart Diagnostics from Tissue. Cancers, 18(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18010009