Patient-Reported Functional Outcomes and Quality of Life After Contact X-Ray Brachytherapy (CXB) in Organ-Preserving Management of Rectal Cancer

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

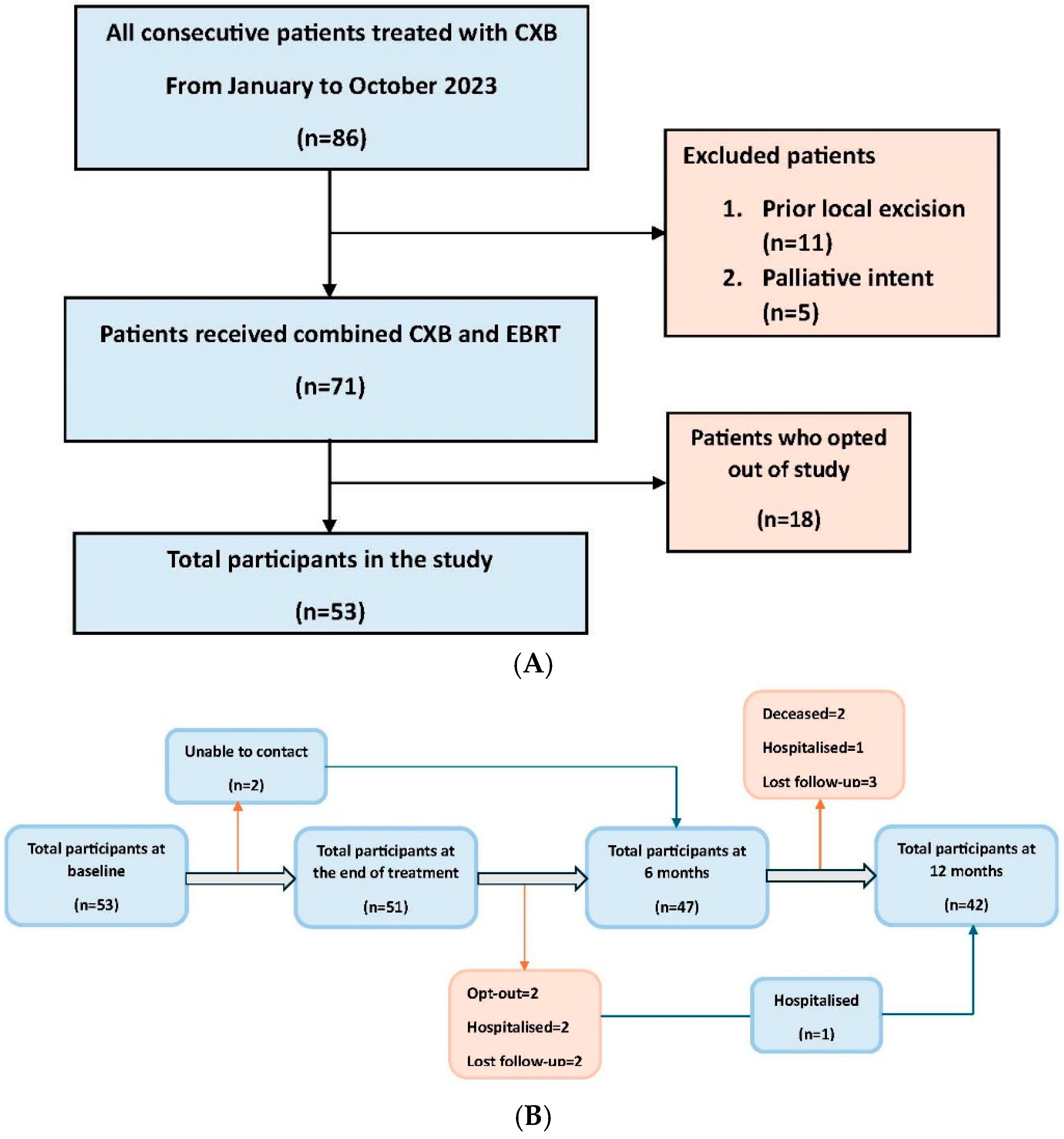

2.1. Patient Selection

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Questionnaires

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

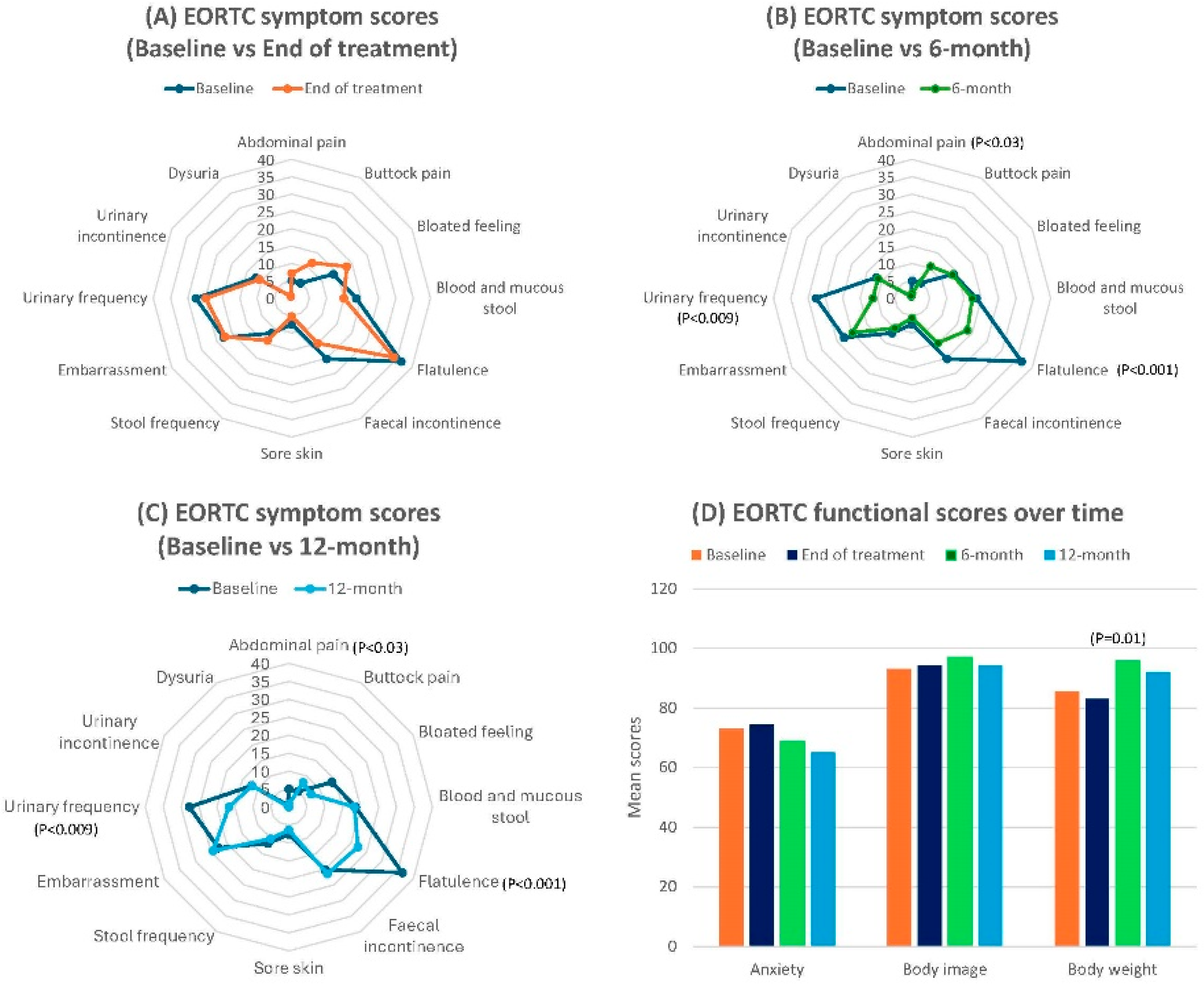

3.1. EORTC-QLQ-CR29 Scores

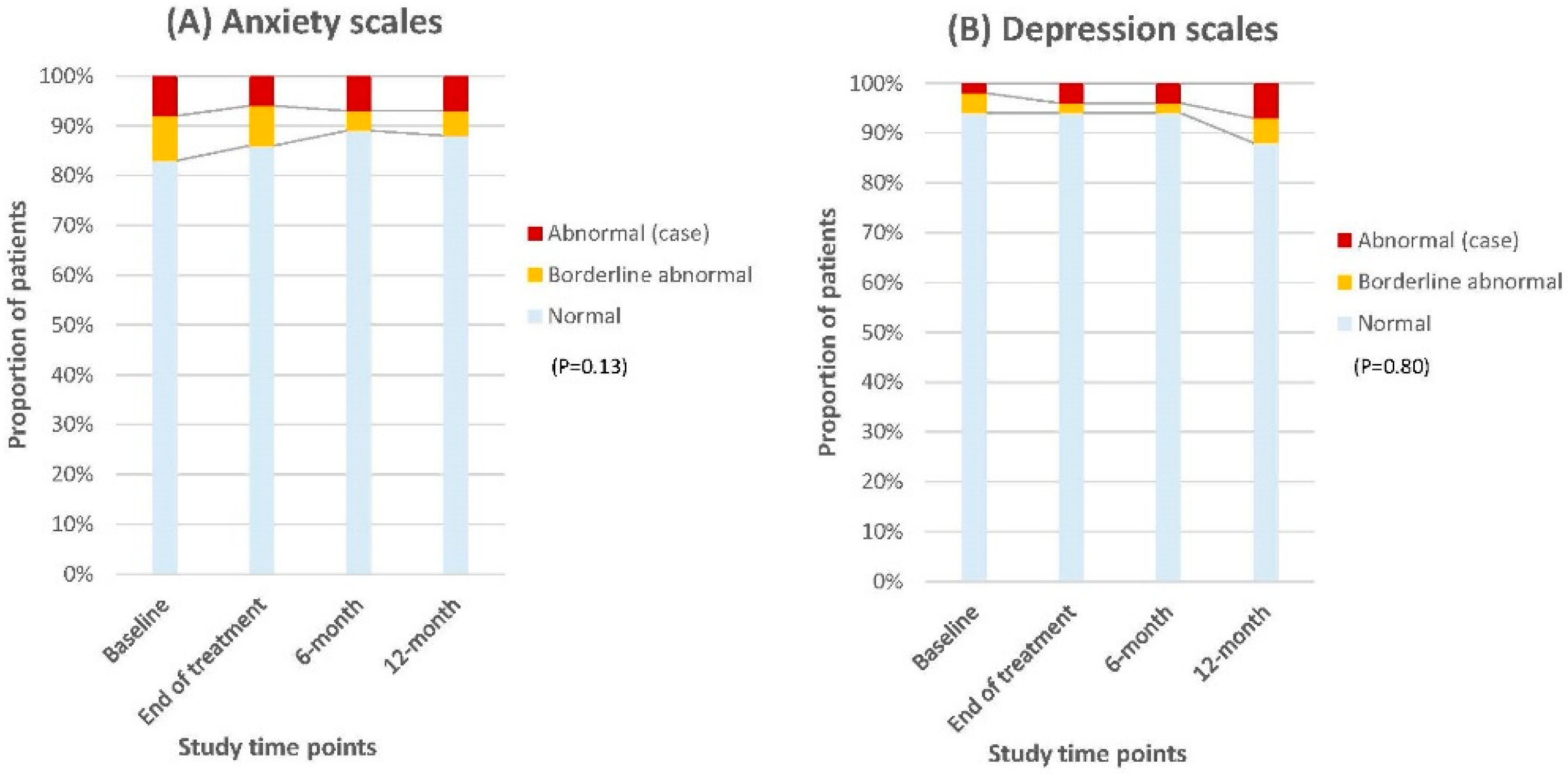

3.2. HADS Scores

3.3. EQ-5D-3L Scores

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Colorectal Cancer. NICE Guideline [NG151]. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng151 (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Guidelines Version 2.2024 Rectal Cancer; National Comprehensive Cancer Network: Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/rectal.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Schmoll, H.J.; Van Cutsem, E.; Stein, A.; Valentini, V.; Glimelius, B.; Haustermans, K.; Nordlinger, B.; van de Velde, C.J.; Balmana, J.; Regula, J.; et al. ESMO Consensus Guidelines for management of patients with colon and rectal cancer. A personalized approach to clinical decision making. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2012, 23, 2479–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daprà, V.; Airoldi, M.; Bartolini, M.; Fazio, R.; Mondello, G.; Tronconi, M.C.; Prete, M.G.; D’Agostino, G.; Foppa, C.; Spinelli, A.; et al. Total Neoadjuvant Treatment for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer Patients: Where Do We Stand? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peeters, K.C.; Marijnen, C.A.; Nagtegaal, I.D.; Kranenbarg, E.K.; Putter, H.; Wiggers, T.; Rutten, H.; Pahlman, L.; Glimelius, B.; Leer, J.W.; et al. The TME trial after a median follow-up of 6 years: Increased local control but no survival benefit in irradiated patients with resectable rectal carcinoma. Ann. Surg. 2007, 246, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, L.; Verre, L.; Carbone, L.; Poto, G.E.; Fusario, D.; Venezia, D.F.; Calomino, N.; Kaźmierczak-Siedlecka, K.; Polom, K.; Marrelli, D.; et al. Current Trends in Volume and Surgical Outcomes in Gastric Cancer. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juul, T.; Ahlberg, M.; Biondo, S.; Espin, E.; Jimenez, L.M.; Matzel, K.E.; Palmer, G.J.; Sauermann, A.; Trenti, L.; Zhang, W.; et al. Low anterior resection syndrome and quality of life: An international multicenter study. Dis. Colon. Rectum 2014, 57, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giandomenico, F.; Gavaruzzi, T.; Lotto, L.; Del Bianco, P.; Barina, A.; Perin, A.; Pucciarelli, S. Quality of life after surgery for rectal cancer: A systematic review of comparisons with the general population. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 9, 1227–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachler, J.; Wille-Jørgensen, P. Quality of life after rectal resection for cancer, with or without permanent colostomy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 12, CD004323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.Y.; Wiltink, L.M.; Nout, R.A.; Meershoek-Klein Kranenbarg, E.; Laurberg, S.; Marijnen, C.A.; van de Velde, C.J. Bowel function 14 years after preoperative short-course radiotherapy and total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: Report of a multicenter randomized trial. Clin. Color. Cancer 2015, 14, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bregendahl, S.; Emmertsen, K.J.; Lindegaard, J.C.; Laurberg, S. Urinary and sexual dysfunction in women after resection with and without preoperative radiotherapy for rectal cancer: A population-based cross-sectional study. Color. Dis. 2015, 17, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulskas, A.; Samalavicius, N.E. A prospective study of sexual and urinary function before and after total mesorectal excision. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2016, 31, 1125–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couwenberg, A.M.; Burbach, J.P.M.; van Grevenstein, W.M.U.; Smits, A.B.; Consten, E.C.J.; Schiphorst, A.H.W.; Wijffels, N.A.T.; Heikens, J.T.; Intven, M.P.W.; Verkooijen, H.M. Effect of Neoadjuvant Therapy and Rectal Surgery on Health-related Quality of Life in Patients With Rectal Cancer During the First 2 Years After Diagnosis. Clin. Color. Cancer 2018, 17, e499–e512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habr-Gama, A.; Gama-Rodrigues, J.; São Julião, G.P.; Proscurshim, I.; Sabbagh, C.; Lynn, P.B.; Perez, R.O. Local recurrence after complete clinical response and watch and wait in rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiation: Impact of salvage therapy on local disease control. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2014, 88, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Valk, M.J.; Hilling, D.E.; Bastiaannet, E.; Kranenbarg, E.M.-K.; Beets, G.L.; Figueiredo, N.L.; Habr-Gama, A.; Perez, R.O.; Renehan, A.G.; van de Velde, C.J. Long-term outcomes of clinical complete responders after neoadjuvant treatment for rectal cancer in the International Watch & Wait Database (IWWD): An international multicentre registry study. Lancet 2018, 391, 2537–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard, J.-P.; Barbet, N.; Schiappa, R.; Magné, N.; Martel, I.; Mineur, L.; Deberne, M.; Zilli, T.; Dhadda, A.; Myint, A.S. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy with radiation dose escalation with contact X-ray brachytherapy boost or external beam radiotherapy boost for organ preservation in early cT2–cT3 rectal adenocarcinoma (OPERA): A phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 8, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verheij, F.S.; Omer, D.M.; Williams, H.; Lin, S.T.; Qin, L.X.; Buckley, J.T.; Thompson, H.M.; Yuval, J.B.; Kim, J.K.; Dunne, R.F.; et al. Long-Term Results of Organ Preservation in Patients with Rectal Adenocarcinoma Treated with Total Neoadjuvant Therapy: The Randomized Phase II OPRA Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manceau, G.; Karoui, M.; Werner, A.; Mortensen, N.J.; Hannoun, L. Comparative outcomes of rectal cancer surgery between elderly and non-elderly patients: A systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13, e525–e536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrenn, S.M.; Cepeda-Benito, A.; Ramos-Valadez, D.I.; Cataldo, P.A. Patient Perceptions and Quality of Life After Colon and Rectal Surgery: What Do Patients Really Want? Dis. Colon. Rectum 2018, 61, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habr-Gama, A.; Lynn, P.B.; Jorge, J.M.N.; São Julião, G.P.; Proscurshim, I.; Gama-Rodrigues, J.; Fernandez, L.M.; Perez, R.O. Impact of Organ-Preserving Strategies on Anorectal Function in Patients with Distal Rectal Cancer Following Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation. Dis. Colon Rectum 2016, 59, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizdarevic, E.; Frøstrup Hansen, T.; Pløen, J.; Henrik Jensen, L.; Lindebjerg, J.; Rafaelsen, S.; Jakobsen, A.; Appelt, A. Long-Term Patient-Reported Outcomes After High-Dose Chemoradiation Therapy for Nonsurgical Management of Distal Rectal Cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2020, 106, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custers, P.A.; van der Sande, M.E.; Grotenhuis, B.A.; Peters, F.P.; van Kuijk, S.M.J.; Beets, G.L.; Breukink, S.O.; Dutch Watch-and-Wait Consortium. Long-term Quality of Life and Functional Outcome of Patients With Rectal Cancer Following a Watch-and-Wait Approach. JAMA Surg. 2023, 158, e230146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H.J.S.; Al-Najami, I.; Cunningham, C. Quality of life after rectal-preserving treatment of rectal cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 46, 2050–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Custers, P.A.; Geubels, B.M.; Huibregtse, I.L.; Peters, F.P.; Engelhardt, E.G.; Beets, G.L.; Marijnen, C.A.M.; van Leerdam, M.E.; van Triest, B. Contact X-ray Brachytherapy for Older or Inoperable Rectal Cancer Patients: Short-Term Oncological and Functional Follow-Up. Cancers 2021, 13, 6333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujral, S.; Conroy, T.; Fleissner, C.; Sezer, O.; King, P.M.; Avery, K.N.L.; Sylvester, P.; Koller, M.; Sprangers, M.A.G.; Blazeby, J.M. Assessing quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer: An update of the EORTC quality of life questionnaire. Eur. J. Cancer 2007, 43, 1564–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EuroQol Research Foundation. EQ-5D-3L User Guide Version 6.0 December 2018; EuroQol Research Foundation: Rotterdam, The Netherlands; Available online: https://euroqol.org/publications/user-guides (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Marsh, H.W. Pairwise deletion for missing data in structural equation models: Nonpositive definite matrices, parameter estimates, goodness of fit, and adjusted sample sizes. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1998, 5, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Osoba, D.; Bezjak, A.; Brundage, M.; Zee, B.; Tu, D.; Pater, J.; Quality of Life Committee of the NCIC CTG. Analysis and interpretation of health-related quality-of-life data from clinical trials: Basic approach of The National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. Eur. J. Cancer 2005, 41, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnetain, F.; Fiteni, F.; Efficace, F.; Anota, A. Statistical Challenges in the Analysis of Health-Related Quality of Life in Cancer Clinical Trials. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 1953–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bascoul-Mollevi, C.; Barbieri, A.; Bourgier, C.; Conroy, T.; Chauffert, B.; Hebbar, M.; Jacot, W.; Juzyna, B.; De Forges, H.; Gourgou, S.; et al. Longitudinal analysis of health-related quality of life in cancer clinical trials: Methods and interpretation of results. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Than, N.W.; Pritchard, D.M.; Duckworth, C.A.; Hughes, D.M.; Wong, H.; Sripadam, R.; Myint, A.S. Contact X-ray brachytherapy (CXB) as a salvage treatment for rectal cancer patients who developed local tumor re-growth after watch-and-wait approach. J. Contemp. Brachytherapy 2024, 16, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Than, N.W.; Pritchard, D.M.; Hughes, D.M.; Duckworth, C.A.; Wong, H.; Haq, M.U.; Sripadam, R.; Myint, A.S. Sequence of Contact X-ray Brachytherapy (CXB) and External Beam Radiation (EBRT) in organ-preserving treatment for small rectal cancer. Radiother. Oncol. J. Eur. Soc. Ther. Radiol. Oncol. 2024, 199, 110465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Than, N.W.; Pritchard, D.M.; Hughes, D.M.; Duckworth, C.A.; Wong, H.; Ul Haq, M.; Sripadam, R.; Myint, A.S. Contact X-ray Brachytherapy as a Boost Therapy After Neoadjuvant (Chemo)Radiation in High-Risk Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2024, in press. [CrossRef]

- Pollack, J.; Holm, T.; Cedermark, B.; Altman, D.; Holmström, B.; Glimelius, B.; Mellgren, A. Late adverse effects of short-course preoperative radiotherapy in rectal cancer. Br. J. Surg. 2006, 93, 1519–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruheim, K.; Guren, M.G.; Dahl, A.A.; Skovlund, E.; Balteskard, L.; Carlsen, E.; Fosså, S.D.; Tveit, K.M. Sexual Function in Males After Radiotherapy for Rectal Cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2010, 76, 1012–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun Myint, A.; Than, N.; Schiappa, R.; Ai-Haq, M.; Sripadam, R.; Rao, C.; Stead, S.; Pritchard, D.; Gérard, J. Radiation dose esclation with contact X-ray brachytherapy (Papillon) and quality of life in patients with rectal cancer: Results from the phase 3 randomised trial OPERA. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, e23180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | (Number of Participants = 53) (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) Age (Years) | 71 (64–77.5) | |

| Sex | Male | 34 (64) |

| Female | 19 (36) | |

| ECOG performance status | 0–1 | 34 (64) |

| 2–3 | 19 (36) | |

| Stage | I | 16 (30) |

| II | 15 (28) | |

| III | 19 (36) | |

| Tx-Nx-Mx | 3 (6) | |

| Distance from the anal verge | ≤6 cm | 38 (72) |

| 7–10 cm | 15 (28) | |

| Treatment intent of CXB | De novo | 12 (23) |

| Residual | 26 (49) | |

| Regrowth | 15 (28) | |

| EBRT regimen | Short course | 22 (41) |

| Long course | 3 (6) | |

| Chemoradiation | 28 (53) | |

| CXB dose | 90 Gy | 42 (79) |

| 110 Gy | 11 (21) | |

| Oncological outcomes | (Number of participants = 53) (%) | Subsequent treatment |

| Clinical complete response | 30 (56) | |

| Residual disease | 21 (40) | APER = 7 Hartmann’s = 1 Palliative colostomy = 3 Palliative chemotherapy = 2 Supportive care = 8 |

| Local regrowth | 2 (4) | Supportive care = 2 |

| Synchronous distant relapse with residual/local regrowth | 4 (7) | Palliative chemotherapy = 2 Supportive care = 2 |

| Isolated distant relapse | 2 (4) | Palliative chemotherapy = 2 |

| Isolated pelvic node relapse | 1 (2) | Stereotactic radiotherapy = 1 |

| Deceased | 3 (6) | |

| EORTC-QLQ-CR29 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain Score | Baseline (Mean ± SD) | End of Treatment (Mean ± SD) | Effect Size | 6-Month (Mean ± SD) | Effect Size | 12-Month (Mean ± SD) | Effect Size | |

| Abdominal pain | 5.03 ± 2.08 | 7.19 ± 2.69 | −0.9 | 1.42 ± 0.99 | 2.2 | 0.79 ± 0.79 | 2.7 | |

| Buttock pain | 5.03 ± 2.08 | 11.76 ± 3.34 | −2.4 | 10.64 ± 3.06 | −2.1 | 7.94 ± 2.96 | −1.1 | |

| Bloated feeling | 13.84 ± 3.86 | 18.30 ± 4.10 | −1.1 | 13.48 ± 2.98 | 0.1 | 7.14 ± 2.90 | 1.9 | |

| Blood and mucous stool | 18.55 ± 3.23 | 15.03 ± 2.69 | 1.2 | 17.38 ± 2.95 | 0.4 | 18.25 ± 3.30 | 0.09 | |

| Flatulence | 36.48 ± 4.51 | 33.99 ± 4.52 | 0.6 | 18.44 ± 3.33 | 4.5 | 22.22 ± 3.71 | 3.5 | |

| Faecal incontinence | 20.13 ± 4.15 | 15.03 ± 3.53 | 1.3 | 14.89 ± 3.01 | 1.4 | 21.43 ± 4.22 | −0.3 | |

| Sore skin | 7.55 ± 2.93 | 5.23 ± 2.16 | 0.9 | 5.67 ± 2.11 | 0.7 | 6.35 ± 2.04 | 0.5 | |

| Stool frequency | 11.64 ± 2.36 | 14.05 ± 2.21 | −1.1 | 9.93 ± 1.87 | 0.8 | 10.16 ± 2.01 | 0.7 | |

| Embarrassment | 22.64 ± 4.38 | 22.22 ± 4.14 | 0.1 | 19.86 ± 4.14 | 0.7 | 24.39 ± 5.59 | −0.4 | |

| Urinary frequency | 27.67 ± 3.48 | 24.84 ± 3.6 | 0.6 | 11.35 ± 2.33 | 3.8 | 16.67 ± 3.64 | 1.7 | |

| Urinary incontinence | 11.94 ± 3.37 | 10.80 ± 2.69 | 0.4 | 11.35 ± 2.47 | 0.2 | 11.84 ± 2.60 | 0.03 | |

| Dysuria | 0.63 ± 0.62 | 0.65 ± 0.65 | −0.03 | 0.71 ± 0.71 | 0.1 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.1 | |

| Sexual symptoms | 29.29 ± 6.77 | 35.63 ± 8.09 | −0.9 | 27.16 ± 7.13 | 0.3 | 30.77 ± 8.04 | 0.2 | |

| Sexual interest | 22.22 ± 4.95 | 25.56 ± 6.33 | −0.6 | 21.79 ± 6.12 | 0.1 | 15.00 ± 5.12 | 1.4 | |

| Anxiety | 72.96 ± 4.12 | 74.51 ± 3.69 | −0.4 | 68.79 ± 4.80 | 0.9 | 65.08 ± 5.07 | 1.7 | |

| Body image | 93.08 ± 2.68 | 94.11 ± 2.84 | −0.4 | 97.00 ± 1.71 | −1.7 | 94.06 ± 2.65 | −0.4 | |

| Body weight | 85.53 ± 24.90 | 83.00 ± 26.97 | 0.1 | 95.74 ± 13.22 | −0.5 | 92.06 ± 16.15 | −0.3 | |

| EQ-5D-3L | ||||||||

| Score | Baseline (Mean ± SD) | End of treatment (Mean ± SD) | Effect size | 6-month (Mean ± SD) | Effect size | 12-month (Mean ± SD) | Effect size | |

| Health index | 0.85 ± 0.19 | 0.85 ± 0.15 | 0.2 | 0.83 ± 0.17 | 0.1 | 0.82 ± 0.16 | 0.2 | |

| EQ-VAS | 70.38 ± 17.15 | 73.92 ± 15.14 | −0.2 | 74.00 ± 17.37 | −0.2 | 77.86 ± 14.78 | −0.5 | |

| HADS | ||||||||

| Score | Baseline N = 53 (%) | End of treatment N = 51 (%) | Score difference | 6-month N = 47 (%) | Score difference | 12-month N = 42 (%) | Score difference | |

| Anxiety | Normal | 44 (83) | 44 (86) | 3 | 42 (89) | 6 | 37 (88) | 5 |

| Borderline | 5 (9) | 4 (8) | 1 | 2 (4) | 5 | 2 (5) | 4 | |

| Abnormal (case) | 4 (8) | 3 (6) | 2 | 3 (7) | 1 | 3 (7) | 1 | |

| Depression | Normal | 50 (94) | 48 (94) | 0 | 44 (94) | 0 | 37 (88) | 6 |

| Borderline | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | 2 | 1 (2) | 2 | 2 (5) | 1 | |

| Abnormal (case) | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 2 | 2 (4) | 2 | 3 (7) | 5 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Than, N.W.; Pritchard, D.M.; Hughes, D.M.; Duckworth, C.A.; Haq, M.U.; Cummings, T.; Jardine, C.; Stead, S.; Sripadam, R.; Myint, A.S. Patient-Reported Functional Outcomes and Quality of Life After Contact X-Ray Brachytherapy (CXB) in Organ-Preserving Management of Rectal Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 1560. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17091560

Than NW, Pritchard DM, Hughes DM, Duckworth CA, Haq MU, Cummings T, Jardine C, Stead S, Sripadam R, Myint AS. Patient-Reported Functional Outcomes and Quality of Life After Contact X-Ray Brachytherapy (CXB) in Organ-Preserving Management of Rectal Cancer. Cancers. 2025; 17(9):1560. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17091560

Chicago/Turabian StyleThan, Ngu Wah, D. Mark Pritchard, David M. Hughes, Carrie A. Duckworth, Muneeb Ul Haq, Thomas Cummings, Charlotte Jardine, Sarah Stead, Rajaram Sripadam, and Arthur Sun Myint. 2025. "Patient-Reported Functional Outcomes and Quality of Life After Contact X-Ray Brachytherapy (CXB) in Organ-Preserving Management of Rectal Cancer" Cancers 17, no. 9: 1560. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17091560

APA StyleThan, N. W., Pritchard, D. M., Hughes, D. M., Duckworth, C. A., Haq, M. U., Cummings, T., Jardine, C., Stead, S., Sripadam, R., & Myint, A. S. (2025). Patient-Reported Functional Outcomes and Quality of Life After Contact X-Ray Brachytherapy (CXB) in Organ-Preserving Management of Rectal Cancer. Cancers, 17(9), 1560. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17091560