Simple Summary

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are immune-mediated conditions with increasing prevalence worldwide. In cases of moderate-to-severe disease, treatment often involves immunosuppressive therapies, biologics, and small molecules, which target specific immune pathways to reduce inflammation. For years, there has been considerable debate regarding the safety of these therapies in patients with a history of cancer, given their immunomodulatory effects. However, emerging evidence indicates that these medications can be used safely in this population when managed with careful consideration. A multidisciplinary approach involving both the treating oncologist and gastroenterologist is essential to weigh the potential risks and benefits for each patient. This ensures personalized and safe treatment strategies, providing optimal care while minimizing the risk of cancer recurrence.

Abstract

The use of advanced therapies, including biologics and small molecules, has become an established clinical practice for the treatment of moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD). However, certain patient populations, such as those with a history of cancer, are often excluded from clinical trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of these therapies. This exclusion has historically left clinicians with limited evidence to guide treatment decisions in this high-risk group. Nevertheless, emerging real-world data and updated guidelines increasingly support the safe use of advanced therapies in patients with a prior malignancy. Risk stratification and a multidisciplinary approach, including oncologist input, remain critical in optimizing patient outcomes by assessing both cancer recurrence risk and disease activity. This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the current evidence, address existing knowledge gaps, and offer practical insights for the management of IBD in patients with a history of cancer.

Keywords:

cancer history; malignancies; inflammatory bowel disease; ulcerative colitis; Crohn’s disease; IBD; UC; CD 1. Introduction

The incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), are increasing worldwide [1]. These conditions are typically lifelong diseases that often present at a young age and are characterized by a natural history of alternating periods of flares and remission [1]. The primary therapeutic goal is to achieve comprehensive disease control [2]. To achieve this outcome, immunosuppressive and immunomodulatory therapies play a fundamental role.

Over the last two decades, the management of IBD has undergone a paradigm shift with the advent of biologic agents and small-molecule therapies [3]. However, alongside their therapeutic benefits, these treatments have introduced new challenges for clinicians. The use of immunosuppressive and immunomodulatory agents, while highly effective, is associated with potential side effects, some of which remain incompletely understood [4]. One critical area of concern is the management of IBD patients with a prior history of cancer. The lack of clarity has contributed to significant hesitancy in prescribing these treatments to this particular patient population [5]. Concerns arise from the potential for immunosuppressors and immunomodulators (IMMs) to diminish the immune surveillance of tumor cells and chronic latent viral infections, such as Epstein–Barr virus and human papillomavirus, provoking direct DNA alterations in organ cells [6].

In recent years, however, insights from large cohort studies have begun to elucidate the safety profile of biologic agents and small molecules in IBD patients with a previous history of malignancy [7].

This review aims to synthesize the latest evidence on this topic, providing an updated perspective to enhance clinical decision-making and improve the management of these complex cases.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a comprehensive search of the Pubmed, Embase, and Scopus databases up until 9 March 2025, with the aim of identifying studies regarding IBD and history of cancer. To achieve this, we employed specific search terms such as ‘cancer’, ’history of cancer’, ’malignancies’, and ’history of malignancies’, in conjunction with ’Crohn’s disease’, ’ulcerative colitis’, ’CD’, ’UC’, ’inflammatory bowel disease’, and ’IBD’. We limited our search to articles published in the English language.

Our screening process involved two independent reviewers (IF and SB) who initially assessed titles and abstracts to identify potentially relevant studies. Subsequently, we examined the full texts of these selected articles to determine their eligibility for inclusion. Additionally, we manually scrutinized the reference lists of these articles to ensure that no relevant studies were overlooked during the electronic search. The final inclusion of abstracts and articles was based on their relevance to our research objectives.

3. Results

3.1. Treating IBD in Patients with a History of Cancer

The term “incident cancer” is used in the medical literature to describe any oncological event following a history of cancer. In the case of a patient with a history of cancer, it can describe local, regional, or metastatic recurrence, as well as the development of a new primary tumor in the same or a different organ [7].

The Cancers Et Surrisque Associé aux Maladies inflammatoires intestinales En France (CESAME) French nationwide observational cohort demonstrated that the overall incidence of cancer was significantly higher in patients with previous cancer than in those without previous cancer with a multivariate adjusted hazard ratio (HR) of 1.9 (95% CI 1.2–3.0; p = 0.003) [7]. In particular, among the 16,642 patients with no prior history of cancer at the start of the study, 293 developed a cancer during the observation period, resulting in an incidence rate of 6.1 per 1000 patient-years. In contrast, among the 405 patients with a history of cancer, 23 developed an incident cancer during the observation period, resulting in an incidence rate of 21.1 per 1000 patient-years [7]. On the other hand, a recent meta-analysis by Gupta et al., which included 24,382 patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs)—among them, 14 studies focusing on IBD—and encompassing 85,784 person-years of follow-up, supports the reassuring evidence that IMMs snd biologic therapies do not significantly impact the risk of developing new primary or recurrent cancers in patients with a prior history of malignancy [8].

3.1.1. Thiopurines

With the advent of biologic agents and small-molecule therapies, the long-term use of thiopurines in the treatment of IBD has significantly declined. Historically, thiopurines played a fundamental role in the therapeutic algorithm for IBD. However, the latest guidelines for the management of CD and UC recommend the cautious use of thiopurines for maintenance therapy [9,10]. This shift is driven by the increased risk of long-term adverse effects associated with thiopurines, including non-melanoma skin cancer, lymphoma, and genitourinary cancers [11].

Despite the established cancer risks associated with thiopurines, evidence does not suggest an additional risk of incident cancer in IBD patients with a prior history of malignancy, as also specified in the latest ECCO guidelines [11]. A meta-analysis by Shelton et al. [12] provides valuable insights into this issue. Among 3706 IBD patients, accounting for 10,332 person-years of follow-up, there were 539 cases of new or recurrent cancer. The pooled incidence rates (IRs) for patients on no immunosuppressive therapy, thiopurines, or tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) antagonists were 35.7 per 1000 person-years, 37.9 per 1000 person-years, and 48.5 per 1000 person-years, respectively. Importantly, there was no statistically significant difference in cancer risk between these groups (p > 0.30 for all comparisons).

The CESAME cohort study further demonstrated that there was no significant difference in the incidence of new or recurrent cancers between patients with a history of cancer exposed to thiopurines or methotrexate and those not exposed to these agents. The rates of incident cancer were 27.0 per 1000 patient-years in patients exposed to immunosuppressants at study entry, compared to 19.2 per 1000 patient-years in those not exposed, with no significant difference between the two groups [7].

The results were corroborated by another large cohort study from the ENEIDA registry. Among 520 IBD patients with a prior history of cancer, 62% were treated with thiopurines alone, 34% were treated with a combination of thiopurines and anti-TNF agents, and 4% were treated with anti-TNF agents alone. The incidence of new cancers was similar between the exposed group (16%) and the non-exposed group (18%), with no statistically significant difference (p = 0.53) [13].

3.1.2. TNFα Antagonist

The data available on the use of TNF-α antagonists in patients with a prior history of cancer are primarily derived from retrospective studies. This is because patients with a previous cancer diagnosis are typically excluded from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) conducted for drug approval. As a result, most of the evidence in this area is based on observational and retrospective analyses [11]. One of the first studies to evaluate IBD patients with a history of cancer who were exposed to both antimetabolites (thiopurines, methotrexate) and anti-TNF therapy demonstrated that immunosuppressive treatment following a cancer diagnosis was not associated with an increased risk of either new or recurrent malignancy. The HR was 0.32 (95% CI: 0.09–1.09) for anti-TNF therapy, 0.64 (95% CI: 0.26–1.59) for combination therapy with anti-TNF and an antimetabolite, and 1.08 (95% CI: 0.54–2.15) for antimetabolite therapy alone. However, it is important to note that this was a retrospective study with a limited sample size of only 90 patients [14]. A 2019 meta-analysis by Micic et al. reviewed nine observational studies including 11,679 patients with IMIDs who were exposed to TNF-α antagonists and had a history of cancer. In a subgroup analysis focused on patients with IBD, no increased risk of new or recurrent cancer was observed following exposure to TNF-α antagonists, with an incidence rate ratio (IRR) of 0.68 (95% CI: 0.40–1.16) [15]. Similarly, a retrospective American study involving 184 IBD patients with a prior history of cancer reported an incidence of new or recurrent cancer of 4.2 per 1000 person-years among those exposed to TNF-α antagonists. This study also found no significant association between anti-TNF therapy and an increased risk of cancer recurrence or new cancer development (HR 1.03; 95% CI: 0.65–1.64). Interestingly, the authors noted that, although the study was not able to evaluate risks for specific cancers, 19 patients in the anti-TNF-α group had received this therapy after a melanoma diagnosis, with 4 experiencing a recurrence [16].

Regarding specific cancers, Khan et al. conducted a cohort study focusing on IBD patients with a history of non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) within the U.S. Veterans Affairs Healthcare System (VAHS). The study reported the following rates of recurrent basal cell carcinoma (BCC) per 100 person-years: 34.5 for those on active thiopurine therapy, 17.8 for those on anti-TNF therapy alone, and 22.4 for patients receiving combined active thiopurine and anti-TNF therapy [17]. Interestingly, among these groups, only active thiopurine use was significantly associated with an increased risk of recurrent BCC compared to 5-aminosalicylates use alone, with an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.65 (95% CI: 1.24–2.19; p = 0.0005) [17].

Also, a recent study from the Rising Educators Academics and Clinicians Helping IBD (REACH-IBD) evaluated 170 patients with a history of recent cancer, with 513 person-years of follow-up. The cohort included patients, 84% of whom had solid-organ malignancies. The incidence rate among patients treated with TNF-α antagonists was 3.4 per 100 person-years, compared to 3.7 per 100 person-years for those treated with non-TNF biologics. There was no significant difference in recurrence-free survival between the two groups (hazard ratio: 0.94; 95% CI: 0.24–3.77) [18].

Based on this evidence, it is clear that TNFα antagonists can generally be used in patients with a history of cancer but that each case should be carefully discussed with oncologists [11].

3.1.3. Vedolizumab and Ustekinumab

Vedolizumab and ustekinumab are considered to be among the safest biologic therapies for patients with IBD. In the meta-analysis by Gupta et al., the rate of incident cancer associated with vedolizumab is reported as 16 per 1000 person-years (95% CI) [8]. This study suggests a numerically lower, albeit statistically insignificant, rate of cancer recurrence with vedolizumab compared to other biologic therapies [8]. Supporting these findings, a retrospective cohort study involving 390 IBD patients with a history of cancer reported that among 37 patients exposed to vedolizumab, 6 developed incident cancer. The adjusted HR was 1.36 (95% CI: 0.27–7.01) [19]. The same study also evaluated 14 patients exposed to ustekinumab, of whom 2 (14%) developed subsequent cancer during a follow-up period of 52 months. Similar to vedolizumab, ustekinumab was associated with an adjusted HR of 0.96 (95% CI: 0.17–5.41), indicating no significant increase in cancer risk [19].

The retrospective study by Vedamurthy et al. analyzed 96 patients who were treated with vedolizumab (VDZ) following a prior cancer diagnosis. The incidence of cancer was 22 per 1000 person-years, with 18 patients either developing new cancers (n = 7) or experiencing a recurrence (n = 11). Notably, the study concluded that VDZ use was not associated with a significantly increased risk of new or recurrent cancers (HR 1.38; 95% CI: 0.38–1.36) [16].

Also, a French cohort study compared 255 IBD patients with a history of cancer who were treated with TNF-α antagonists to 30 patients treated with vedolizumab. The incident cancer-free survival rates were not significantly different between the two groups (p = 0.56). The adjusted cancer incidence rates per 1000 person-years were 41.4 (95% CI: 30.9–57.6) in the anti-TNF group and 33.6 (95% CI: 24.5–48.8) in the vedolizumab group. Notably, in a multivariate Cox model, the choice of the first treatment initiated after cancer diagnosis was independently associated with a reduction in incident cancer-free survival rates [20] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Incidence of new or recurrent cancer in patients with IBD and a history of cancer: results from available cohort studies. PYs, person-years; IMMs, immunomodulators; Anti-TNF, anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; VDZ, vedolizumab; UST, ustekinumab; NMSC, non-melanoma skin cancer.

3.1.4. JAK Inhibitors

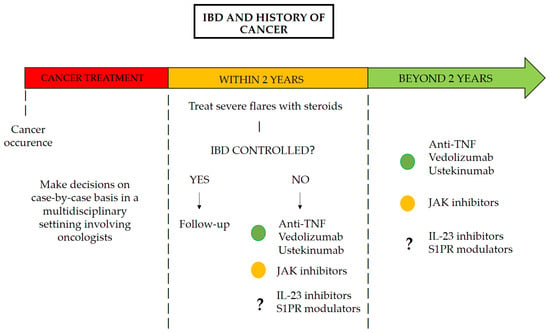

The use of Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors in patients with a history of cancer remains a subject of debate, particularly following the European Medicines Agency (EMA) warning based on findings from the study by Ytterberg et al. on tofacitinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis [24,25]. In this randomized, open-label, noninferiority trial, Ytterberg and colleagues demonstrated that the incidence of cancer was higher among patients exposed to tofacitinib compared to those receiving TNF-α inhibitors, with an HR of 1.48 (95% CI: 1.04–2.09) [25]. Although this has not been proven in patients with IBD, there is currently insufficient evidence to refute it. In fact, no prospective or retrospective studies have evaluated the safety of JAK inhibitors in this population, and the latest meta-analyses do not include studies evaluating JAK inhibitors [8]. An interim analysis of the ongoing Safety of Immunosuppression in a Prospective Cohort of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients With a History of Cancer (SAPPHIRE) registry is the only study to date that has included JAK inhibitors in its evaluation [5]. The final cohort consisted of 305 patients, of whom 210 (69%) were exposed to immunosuppressive therapy during follow-up, while 95 (31%) were not. The incidence rate of new or recurrent cancer among patients who were never exposed to immunosuppression after their cancer was 2.58 per 100 person-years (95% CI: 1.24–4.75). In contrast, patients who received any immunosuppressive therapy had an incidence rate of 4.78 per 100 person-years (95% CI: 3.35–6.62). Notably, among the cohort, 13 patients were exposed to JAK inhibitors, with an incidence rate of new or recurrent cancer of 8.58 per 100 person-years (95% CI: 1.04–31.00) [5]. There is therefore not enough evidence to date to conclude whether or not JAK inhibitors can be used in patients with a history of cancer [11]. Figure 1 presents a potential pathway for the management of patients with IBD who have a history of cancer.

Figure 1.

Pathway for the management of patients with IBD with a history of cancer.

4. Discussion

The concern regarding the potential impact of biologic therapies on cancer risk originates from the biological mechanisms underlying their targets. For TNF-α antagonists, the theoretical concern arises from the dual role of TNF-α in malignancy. On the one hand, TNF-α exerts an antitumor effect by inducing apoptosis in malignant cells, raising the concern that inhibiting this cytokine may impair tumor surveillance, potentially causing the recurrence or rapid progression of cancer. On the other hand, TNF-α can facilitate tumor growth by promoting the survival and proliferation of neoplastic cells through the nuclear factor-κB signaling pathway [26,27,28]. This paradox highlights the complexity of TNF-α in the context of malignancy and underscores the need for careful consideration when prescribing TNF-α inhibitors to patients with a history of cancer. In contrast, the mechanism of action of vedolizumab is more selective, as it targets the gut-specific α4β7 integrin. This selective action is associated with a reduced risk of systemic immunosuppression, potentially making it a safer therapeutic option for patients with a history of cancer [29]. Unfortunately, there are still limited data available regarding the safety of recently approved molecules such as selective IL-23 inhibitors in patients with IBD. However, reassuring evidence regarding their safety profile has been derived from their use in other immune-mediated diseases [30]. The established safety profile of ustekinumab, an IL-12 and IL-23 inhibitor, supports the assumption that selective IL-23 inhibitors may also be safe in this patient population [18,23]. Reassuring data on the safety of JAK inhibitors are also emerging from cohorts such as the SAPPHIRE registry [5]. On the other hand, data on S1P receptor modulators remain limited. This drug class, particularly ozanimod and etrasimod, has only recently received EMA approval for the treatment of ulcerative colitis, and the registrational trials did not include patients with a recent history of cancer [31,32].

Regarding the timing of biologic initiation following a cancer diagnosis, current guidelines generally recommend a waiting period of at least two years before considering biologic therapy [11]. However, this recommendation is largely based on expert opinion rather than high-quality evidence, as prospective data on this topic are scarce. The optimal timing of biologic therapy remains an area of uncertainty, and treatment decisions should be individualized, taking into account both the activity of IBD and the patient’s oncologic history.

Multidisciplinary discussions involving gastroenterologists and oncologists are essential in this context. These meetings are crucial to assess the activity or remission status of the neoplasia and to determine whether biologic therapy is warranted based on the activity of IBD and the risk of cancer recurrence. The stratification of patients based on factors such as the type of prior malignancy, time since diagnosis, and current cancer-free status should inform therapeutic decisions [33]. High-risk patients may require more conservative approaches, whereas low-risk individuals might be candidates for biologic therapy earlier in the course of their IBD management.

An additional challenge involves the lack of data on the use of dual therapy in patients with a history of cancer. Dual therapy is often required in cases with extraintestinal manifestations or refractory disease. However, the absence of studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of dual therapy in this context leaves clinicians without clear guidance, highlighting a need for further research [34].

Finally, the available evidence on biologic therapy in patients with IBD and a history of cancer is predominantly derived from retrospective cohort studies. While these studies provide valuable insights, their inherent limitations, including potential biases and lack of standardization, underscore the need for prospective, randomized controlled trials and real-world data. Addressing these gaps in the literature is essential to optimize the management of IBD in patients with a history of cancer. The I-CARE program [4], along with the TREAT [35] and ENCORE [36] registries, are all valuable sources of long-term safety data. These registries will ultimately provide definitive insights into the safety profile of advanced treatments in IBD.

5. Conclusions

The management of IBD in patients with a history of cancer remains a complex clinical challenge, with decisions requiring the careful consideration of cancer recurrence risk, IBD activity, and the safety profile of available therapies. Significant gaps remain, particularly regarding the timing of therapy initiation, the role of dual therapy, and the safety of newer agents. Multidisciplinary collaboration and patient stratification are essential in individualized care. Prospective studies and real-world data are needed to guide evidence-based treatment strategies.

Author Contributions

F.D. and S.D. conceived the study. I.F. and S.B. wrote the article and created tables and figures. M.A., F.F., A.Z., T.L.P., C.C., V.S., L.P.-B., S.D. and F.D. critically reviewed the content of the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were generated or analyzed in support of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

F D’Amico has served as a speaker for Abbvie, Ferring, Lilly, Sandoz, Janssen, Galapagos, Takeda, Tillotts, and Omega Pharma; he also served as an advisory board member for Abbvie, AnaptysBio, Ferring, Fresenius Kabi, Galapagos, Janssen, Lilly, Takeda, and Nestlé. M Allocca has received consulting fees from Nik-372 kiso Europe, Mundipharma, Janssen, AbbVie, Ferring, and Pfizer. F Furfaro received consulting fees 373 from Amgen and AbbVie and lecture fees from Janssen and Pfizer. A Zilli received lecture fees from AbbVie, Galapagos, Janssen, Tillots Pharma, and Takeda and served as a consultant for AbbVie and Galapagos. Laurent Peyrin-Biroulet declares personal fees from Galapagos, AbbVie, Janssen, Genentech, Ferring, Tillots, Celltrion, Takeda, Pfizer, Index Pharmaceuticals, Sandoz, Celgene, Biogen, Samsung Bioepis, Inotrem, Allergan, MSD, Roche, Arena, Gilead, Amgen, BMS, Vifor, Norgine, Mylan, Lilly, Fresenius Kabi, OSE Immuno-therapeutics, Enthera, Theravance, Pandion Therapeutics, Gossamer Bio, Viatris, and Thermo Fisher, grants from Abbvie, MSD, Takeda, and Fresenius Kabi, and stock options from CTMA. S Danese has served as a speaker, consultant, and advisory board member for Schering-Plough, AbbVie, Actelion, Alphawasserman, AstraZeneca, Cellerix, Cosmo Pharmaceuticals, Ferring, Genentech, Grunenthal, Johnson and Johnson, Millenium Takeda, MSD, Nikkiso Europe GmbH, Novo Nordisk, Nycomed, Pfizer, Pharmacosmos, UCB Pharma, and Vifor. I Faggiani, S Bencardino, T L Parigi, and V Solitano declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ng, S.C.; Shi, H.Y.; Hamidi, N.; Underwood, F.E.; Tang, W.; Benchimol, E.I.; Panaccione, R.; Ghosh, S.; Wu, J.C.Y.; Chan, F.K.L.; et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: A systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet 2017, 390, 2769–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, D.; Ricciuto, A.; Lewis, A.; D’amico, F.; Dhaliwal, J.; Griffiths, A.M.; Bettenworth, D.; Sandborn, W.J.; Sands, B.E.; Reinisch, W.; et al. STRIDE-II: An Update on the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) Initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 1570–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolò, S.; Faggiani, I.; Errico, C.; D’amico, F.; Parigi, T.L.; Danese, S.; Ungaro, F. Translational characterization of immune pathways in inflammatory bowel disease: Insights for targeted treatments. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2025, 21, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Rahier, J.-F.; Kirchgesner, J.; Abitbol, V.; Shaji, S.; Armuzzi, A.; Gisbert, J.P.; Bossuyt, P.; Helwig, U.; Burisch, J.; et al. I-CARE, a European Prospective Cohort Study Assessing Safety and Effectiveness of Biologics in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2023, 21, 771–788.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itzkowitz, S.H.; Jiang, Y.; Villagra, C.; Colombel, J.-F.; Sultan, K.; Lukin, D.J.; Faleck, D.M.; Scherl, E.; Chang, S.; Chen, L.; et al. Safety of Immunosuppression in a Prospective Cohort of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients with a HIstoRy of CancEr: SAPPHIRE Registry. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2024, 23, 855–865.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münz, C.; Moormann, A. Immune escape by Epstein-Barr virus associated malignancies. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2008, 18, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaugerie, L.; Carrat, F.; Colombel, J.-F.; Bouvier, A.-M.; Sokol, H.; Babouri, A.; Carbonnel, F.; Laharie, D.; Faucheron, J.-L.; Simon, T.; et al. Risk of new or recurrent cancer under immunosuppressive therapy in patients with IBD and previous cancer. Gut 2014, 63, 1416–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N. Risk of Cancer Recurrence in Patients with Immune-Mediated Diseases with Use of Immunosuppressive Therapies: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2024, 22, 499–512.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, H.; Minozzi, S.; Kopylov, U.; Verstockt, B.; Chaparro, M.; Buskens, C.; Warusavitarne, J.; Agrawal, M.; Allocca, M.; Atreya, R.; et al. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Crohn’s Disease: Medical Treatment. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2024, 18, 1531–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, T.; Bonovas, S.; Burisch, J.; Kucharzik, T.; Adamina, M.; Annese, V.; Bachmann, O.; Bettenworth, D.; Chaparro, M.; Czuber-Dochan, W.; et al. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Ulcerative Colitis: Medical Treatment. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2022, 16, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, H.; Biancone, L.; Fiorino, G.; Katsanos, K.H.; Kopylov, U.; Al Sulais, E.; Axelrad, J.E.; Balendran, K.; Burisch, J.; de Ridder, L.; et al. ECCO Guidelines on Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Malignancies. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2023, 17, 827–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelton, E.; Laharie, D.; Scott, F.I.; Mamtani, R.; Lewis, J.D.; Colombel, J.-F.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N. Cancer Recurrence Following Immune-Suppressive Therapies in Patients with Immune-Mediated Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2016, 151, 97–109.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mañosa, M.; Chaparro, M.; Juan, A.; Aràjol, C.; Alfaro, I.; Mínguez, M.; Velayos, B.; Benítez, J.; Mesonero, F.; Sicilia, B.; et al. Immunomodulatory Therapy Does Not Increase the Risk of Cancer in Persons with Inflammatory Bowel Disease and a History of Extracolonic Cancers. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 114, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrad, J.; Bernheim, O.; Colombel, J.-F.; Malerba, S.; Ananthakrishnan, A.; Yajnik, V.; Hoffman, G.; Agrawal, M.; Lukin, D.; Desai, A.; et al. Risk of New or Recurrent Cancer in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Previous Cancer Exposed to Immunosuppressive and Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Agents. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2016, 14, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micic, D.; Komaki, Y.; Alavanja, A.; Rubin, D.T.; Sakuraba, A. Risk of Cancer Recurrence Among Individuals Exposed to Antitumor Necrosis Factor Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2019, 53, e1–e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vedamurthy, A.; Gangasani, N.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N. Vedolizumab or Tumor Necrosis Factor Antagonist Use and Risk of New or Recurrent Cancer in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease with Prior Malignancy: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2022, 20, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Patel, D.; Trivedi, C.; Kavani, H.; Medvedeva, E.; Pernes, T.; Xie, D.; Lewis, J.; Yang, Y.-X. Repeated Occurrences of Basal Cell Cancer in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease Treated with Immunosuppressive Medications. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, 1246–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmer, A.K.; Luo, J.; Russ, K.B.; Park, S.; Yang, J.Y.; Ertem, F.; Dueker, J.; Nguyen, V.; Hong, S.; Zenger, C.; et al. Comparative Safety of Biologic Agents in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease with Active or Recent Malignancy: A Multi-Center Cohort Study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 21, 1598–1606.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.J.; Zenger, C.; Pecoriello, J.; Pang, A.; Vallely, M.; Hudesman, D.P.; Chang, S.; Axelrad, J.E. Ustekinumab and Vedolizumab Are Not Associated with Subsequent Cancer in IBD Patients with Prior Malignancy. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2022, 28, 1826–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poullenot, F.; Amiot, A.; Nachury, M.; Viennot, S.; Altwegg, R.; Bouhnik, Y.; Abitbol, V.; Nancey, S.; Vuitton, L.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; et al. Comparative Risk of Incident Cancer in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease with Prior Non-digestive Malignancy According to Immunomodulator: A Multicentre Cohort Study. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2022, 16, 1523–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onali, S.; Petruzziello, C.; Ascolani, M.; Calabrese, E.; Ruffa, A.; Lolli, E.; Pallone, F.; Biancone, L. P278. Thiopurines and Anti-Tnfs in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease and a Positive History of Cancer. J. Crohns Colitis 2015, 9 (Suppl. S1), S215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poullenot, F.; Seksik, P.; Beaugerie, L.; Amiot, A.; Nachury, M.; Abitbol, V.; Stefanescu, C.; Reenaers, C.; Fumery, M.; Pelletier, A.-L.; et al. Risk of Incident Cancer in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients Starting Anti-TNF Therapy While Having Recent Malignancy. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 1362–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, B.; Tandon, K.S.; Miret, R.; Khan, S.; Riaz, A.; Gonzalez, A.; Rahman, A.U.; Charles, R.; Narula, N.; Castro, F.J. Ustekinumab does not increase risk of new or recurrent cancer in inflammatory bowel disease patients with prior malignancy. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 37, 1016–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Janus Kinase Inhibitors (JAKi)-Referral. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/referrals/janus-kinase-inhibitors-jaki (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Ytterberg, S.R.; Bhatt, D.L.; Mikuls, T.R.; Koch, G.G.; Fleischmann, R.; Rivas, J.L.; Germino, R.; Menon, S.; Sun, Y.; Wang, C.; et al. Cardiovascular and Cancer Risk with Tofacitinib in Rheumatoid Arthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, M.L.; Obermueller, E.; Maisey, N.R.; Hoare, S.; Edmonds, K.; Li, N.F.; Chao, D.; Hall, K.; Lee, C.; Timotheadou, E.; et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha as a new target for renal cell carcinoma: Two sequential phase II trials of infliximab at standard and high dose. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 4542–4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jatoi, A.; Ritter, H.L.; Dueck, A.; Nguyen, P.L.; Nikcevich, D.A.; Luyun, R.F.; Mattar, B.I.; Loprinzi, C.L. A placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of infliximab for cancer-associated weight loss in elderly and/or poor performance non-small cell lung cancer patients (N01C9). Lung Cancer 2010, 68, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedenmann, B.; Malfertheiner, P.; Friess, H.; Ritch, P.; Arseneau, J.; Mantovani, G.; Caprioni, F.; Van Cutsem, E.; Richel, D.; DeWitte, M.; et al. A multicenter, phase II study of infliximab plus gemcitabine in pancreatic cancer cachexia. J. Support. Oncol. 2008, 6, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rogler, G. Mechanism of action of vedolizumab: Do we really understand it? Gut 2019, 68, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, K.B.; Lebwohl, M.; Papp, K.; Bachelez, H.; Wu, J.; Langley, R.; Blauvelt, A.; Kaplan, B.; Shah, M.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Long-term safety of risankizumab from 17 clinical trials in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2022, 186, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMA. “Zeposia”, European Medicines Agency. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/zeposia (accessed on 26 April 2023).

- Velsipity. European Medicines Agency (EMA). Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/velsipity (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Fanizza, J.; Bencardino, S.; Allocca, M.; Furfaro, F.; Zilli, A.; Parigi, T.L.; Fiorino, G.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Danese, S.; D’amico, F. Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Huang, Y.-H.; Jiang, M. Combination therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: Current evidence and perspectives. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 114, 109545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtenstein, G.R. The TREAT Registry: Evolution of Knowledge From 1999 to 2017: Lessons Learned. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 15, 1319–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Haens, G.; Reinisch, W.; Colombel, J.-F.; Panes, J.; Ghosh, S.; Prantera, C.; Lindgren, S.; Hommes, D.W.; Huang, Z.; Boice, J.; et al. Five-year Safety Data from ENCORE, a European Observational Safety Registry for Adults with Crohn’s Disease Treated with Infliximab [Remicade®] or Conventional Therapy. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2017, 11, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).