Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Cognition in Adults with Cancer: A Scoping Review

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Management and Synthesis

3. Results

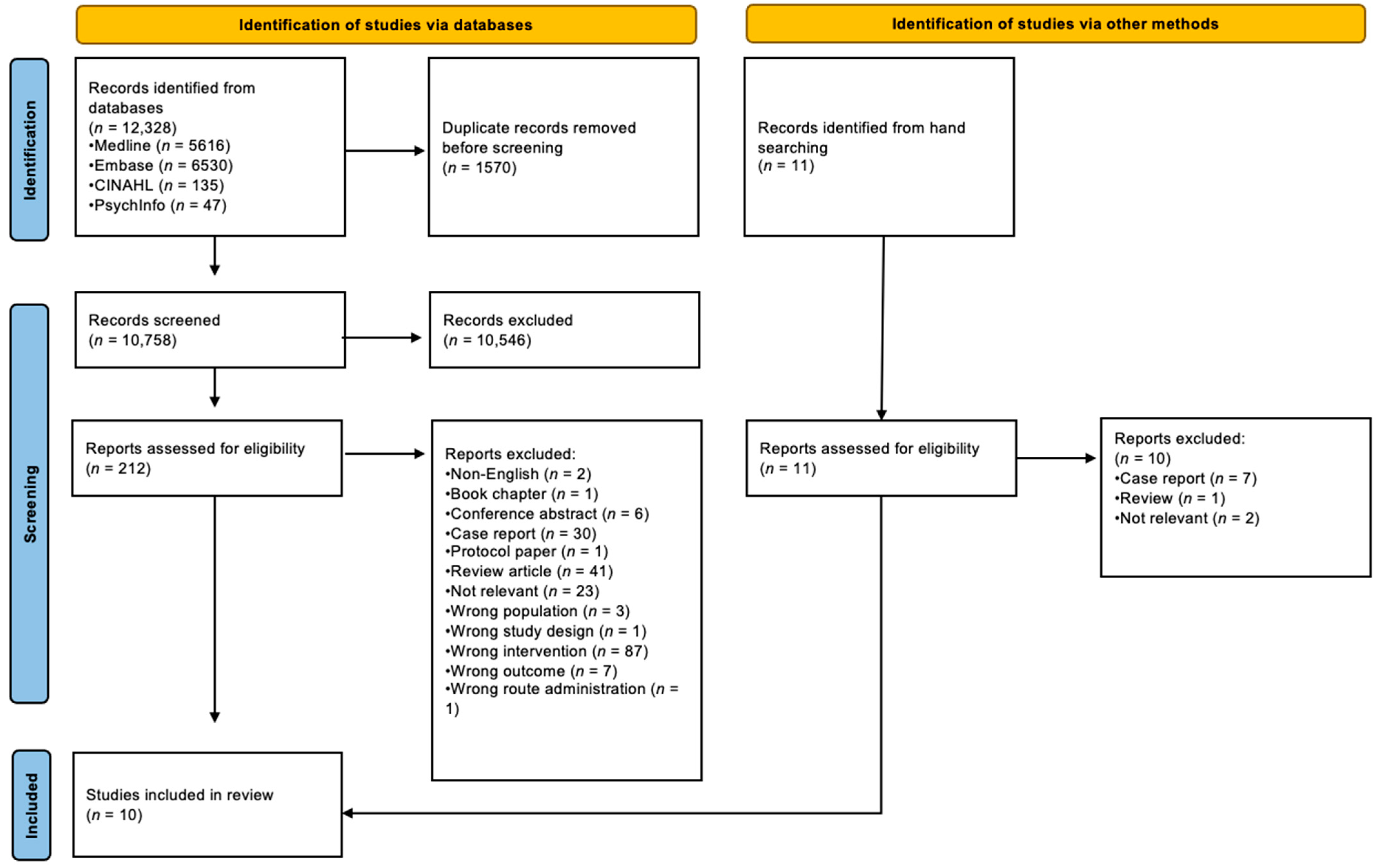

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Studies Included

3.3. Other Studies/Reports Identified

3.4. Objective Cognitive Assessment Tools Utilised

3.5. Subjective Cognitive Assessment Tools Utilised

3.6. Change in Objective Cognition During ICI Treatment

3.7. Change in Subjective Cognition During ICI Treatment

3.8. Subjective Cognition in “Cancer Survivors” (Following ICI Treatment)

3.9. Cognition in Older Persons (Versus Younger Persons)

3.10. Subjective Cognition vs. Objective Cognition

3.11. Cognitive Function and Specific ICI Therapies

4. Discussion

- (a)

- What are the short-term/long-term effects of ICIs on objective cognition (and what domains of cognition are affected)?

- (b)

- What are the short-term/long-term effects of ICIs on subjective cognition?

- (c)

- What factors predispose to ICI-related cognitive impairment (e.g., age, gender, comorbidities, pre-existing cognitive impairment, presence of cerebral metastases, ICI regimen, previous anticancer treatment)?

- (d)

- Why is there limited concordance between subjective complaints and objective evidence of cognitive impairment?

- (e)

- What is the underlying mechanism of ICI-related cognitive impairment?

- (f)

- What are the optimal interventions for preventing/treating ICI-related cognitive impairment?

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahles, T.A.; Root, J.C. Cognitive Effects of Cancer and Cancer Treatments. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 14, 425–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, N.; Fawcett, J.M.; Rash, J.A.; Lester, R.; Powell, E.; MacMillan, C.D.; Garland, S.N. Factors associated with cognitive impairment during the first year of treatment for nonmetastatic breast cancer. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 1191–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurria, A.; Somlo, G.; Ahles, T. Renaming “chemobrain”. Cancer Investig. 2007, 25, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilder, C.M.; Seynaeve, C.; Beex, L.V.; Boogerd, W.; Linn, S.C.; Gundy, C.M.; Huizenga, H.M.; Nortier, J.W.; van de Velde, C.J.; van Dam, F.S.; et al. Effects of tamoxifen and exemestane on cognitive functioning of postmenopausal patients with breast cancer: Results from the neuropsychological side study of the tamoxifen and exemestane adjuvant multinational trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 1294–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, K.D.; Hutchinson, A.D.; Wilson, C.J.; Nettelbeck, T. A meta-analysis of the effects of chemotherapy on cognition in patients with cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2013, 39, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulder, S.F.; Bertens, D.; Desar, I.M.; Vissers, K.C.; Mulders, P.F.; Punt, C.J.; van Spronsen, D.J.; Langenhuijsen, J.F.; Kessels, R.P.; van Herpen, C.M. Impairment of cognitive functioning during Sunitinib or Sorafenib treatment in cancer patients: A cross sectional study. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilleron, S.; Sarfati, D.; Janssen-Heijnen, M.; Vignat, J.; Ferlay, J.; Bray, F.; Soerjomataram, I. Global cancer incidence in older adults, 2012 and 2035: A population-based study. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 144, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, S.; Haque, M.E.; Balakrishnan, R.; Kim, I.-S.; Choi, D.-K. The Ageing Brain: Molecular and Cellular Basis of Neurodegeneration. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 683459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inouye, S.K.; Westendorp, R.G.J.; Saczynski, J.S. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet 2014, 383, 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, B.J.; Zhang, X.; Sun, M.; Holmes, H.M.; Ketonen, L.; Guha, N.; Khalil, P.; Song, J.; Kesler, S.; Shah, J.B.; et al. Neurocognitive deficits in older patients with cancer. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2018, 9, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerstens, C.; Wildiers, H.; Schroyen, G.; Almela, M.; Mark, R.E.; Lambrecht, M.; Deprez, S.; Sleurs, C. A Systematic Review on the Potential Acceleration of Neurocognitive Aging in Older Cancer Survivors. Cancers 2023, 15, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utne, I.; Løyland, B.; Grov, E.K.; Rasmussen, H.L.; Torstveit, A.H.; Paul, S.M.; Ritchie, C.; Lindemann, K.; Vistad, I.; Rodríguez-Aranda, C.; et al. Age-related differences in self-report and objective measures of cognitive function in older patients prior to chemotherapy. Nurs. Open 2022, 9, 1040–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, P.; Salvalaggio, A.; Argyriou, A.A.; Bruna, J.; Visentin, A.; Cavaletti, G.; Briani, C. Neurological Complications of Conventional and Novel Anticancer Treatments. Cancers 2022, 14, 6088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, J.H.; Chan, L.C.; Song, M.S.; Hung, M.C. New Approaches on Cancer Immunotherapy. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2020, 10, a036863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kciuk, M.; Yahya, E.B.; Mohamed Ibrahim Mohamed, M.; Rashid, S.; Iqbal, M.O.; Kontek, R.; Abdulsamad, M.A.; Allaq, A.A. Recent Advances in Molecular Mechanisms of Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancers 2023, 15, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marin, I.; Kipnis, J. Learning and memory … and the immune system. Learn. Mem. 2013, 20, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, D.; Kovacs, P.; Eszlari, N.; Gonda, X.; Juhasz, G. Psychological side effects of immune therapies: Symptoms and pathomechanism. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2016, 29, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.; Cheung, Y.T.; Ng, Q.S.; Ho, H.K.; Chan, A. Vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors and cognitive impairment: Evidence and controversies. Expert. Opin. Drug Saf. 2014, 13, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, C.; Anderson, M.A.; Kuznetsova, V.; Rosenfeld, H.; Malpas, C.B.; Roos, I.; Dickinson, M.; Harrison, S.; Kalincik, T. Patterns of neurotoxicity among patients receiving chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy: A single-centre cohort study. Eur. J. Neurol. 2024, 31, e16174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahli, M.N.; Hayoz, S.; Hoch, D.; Ryser, C.O.; Hoffmann, M.; Scherz, A.; Schwacha-Eipper, B.; Häfliger, S.; Wampfler, J.; Berger, M.D.; et al. The role of immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical practice: An analysis of the treatment patterns, survival and toxicity rates by sex. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 3847–3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.J.; Dougan, S.K.; Dougan, M. Immune mechanisms of toxicity from checkpoint inhibitors. Trends Cancer 2023, 9, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naimi, A.; Mohammed, R.N.; Raji, A.; Chupradit, S.; Yumashev, A.V.; Suksatan, W.; Shalaby, M.N.; Thangavelu, L.; Kamrava, S.; Shomali, N.; et al. Tumor immunotherapies by immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs); the pros and cons. Cell Commun. Signal. 2022, 20, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Social. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGowan, J.; Straus, S.; Moher, D.; Langlois, E.V.; O’Brien, K.K.; Horsley, T.; Aldcroft, A.; Zarin, W.; Garitty, C.M.; Hempel, S.; et al. Reporting scoping reviews-PRISMA ScR extension. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 123, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuzzubbo, S.; Belin, C.; Chouahnia, K.; Baroudjian, B.; Duchemann, B.; Barlog, C.; Coarelli, G.; Ursu, R.; Poirier, E.; Lebbe, C.; et al. Assessing cognitive function in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A feasibility study. Psycho-Oncol. 2018, 27, 1861–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogiers, A.; Leys, C.; De Cremer, J.; Awada, G.; Schembri, A.; Theuns, P.; De Ridder, M.; Neyns, B. Health-related quality of life, emotional burden, and neurocognitive function in the first generation of metastatic melanoma survivors treated with pembrolizumab: A longitudinal pilot study. Support. Care Cancer Off. J. Multinatl. Assoc. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 3267–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogiers, A.; Leys, C.; Lauwyck, J.; Schembri, A.; Awada, G.; Schwarze, J.K.; De Cremer, J.; Theuns, P.; Maruff, P.; De Ridder, M.; et al. Neurocognitive Function, Psychosocial Outcome, and Health-Related Quality of Life of the First-Generation Metastatic Melanoma Survivors Treated with Ipilimumab. J. Immunol. Res. 2020, 2020, 2192480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boekhout, A.H.; Rogiers, A.; Jozwiak, K.; Boers-Sonderen, M.J.; van den Eertwegh, A.J.; Hospers, G.A.; de Groot, J.W.B.; Aarts, M.J.B.; Kapiteijn, E.; ten Tije, A.J.; et al. Health-related quality of life of long-term advanced melanoma survivors treated with anti-CTLA-4 immune checkpoint inhibition compared to matched controls. Acta Oncol. 2021, 60, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Invitto, S.; Leucci, M.; Accogli, G.; Schito, A.; Nestola, C.; Ciccarese, V.; Rinaldi, R.; Boscolo Rizzo, P.; Spinato, G.; Leo, S. Chemobrain, Olfactory and Lifestyle Assessment in Onco-Geriatrics: Sex-Mediated Differences between Chemotherapy and Immunotherapy. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Liu, N.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, A.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Jian, G.; Fu, G.; Dong, M.; et al. Cognitive adverse events in patients with lung cancer treated with checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy: A propensity score-matched analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 59, 101987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, J.S.; Parks, A.C.; Mahnken, J.D.; Young, K.J.; Pathak, H.B.; Puri, R.V.; Unrein, A.; Switzer, P.; Abdulateef, Y.; Sullivan, S.; et al. First-Line Immunotherapy with Check-Point Inhibitors: Prospective Assessment of Cognitive Function. Cancers 2023, 15, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogiers, A.; Willemot, L.; McDonald, L.; Van Campenhout, H.; Berchem, G.; Jacobs, C.; Blockx, N.; Rorive, A.; Neyns, B. Real-World Effectiveness, Safety, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients Receiving Adjuvant Nivolumab for Melanoma in Belgium and Luxembourg: Results of PRESERV MEL. Cancers 2023, 15, 4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suazo-Zepeda, E.; Vinke, P.C.; Heuvelmans, M.A.; Sidorenkov, G.; Hiltermann, T.J.N.; de Bock, G.H. Quality of life after treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors for lung cancer; the impact of age. Lung Cancer 2023, 176, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanlaer, N.; Dirven, I.; Neyns, B.; Rogiers, A. Emotional Distress, Cognitive Complaints, and Care Needs among Advanced Cancer Survivors Treated with Immune Checkpoint Blockade: A Mixed-Method Study. Cancers 2024, 16, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillet, D.; Matharan, F.; Le Clésiau, H.; Bailon, O.; Pérès, K.; Amieva, H.; Belin, C. TNI-93: A New Memory Test for Dementia Detection in Illiterate and Low-Educated Patients. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2016, 31, 896–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenvold, M.; Klee, M.C.; Sprangers, M.A.; Aaronson, N.K. Validation of the EORTC QLQ-C30 quality of life questionnaire through combined qualitative and quantitative assessment of patient-observer agreement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1997, 50, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, J.; Maruff, P.; Woodward, M.; Moore, L.; Fredrickson, A.; Sach, J.; Darby, D. Evaluation of the usability of a brief computerized cognitive screening test in older people for epidemiological studies. Neuroepidemiology 2010, 34, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, A.; Singer, S.; Brähler, E. European reference values for the quality of life questionnaire EORTC QLQ-C30: Results of a German investigation and a summarizing analysis of six European general population normative studies. Acta Oncol. 2014, 53, 958–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broadbent, D.E.; Cooper, P.F.; FitzGerald, P.; Parkes, K.R. The Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ) and its correlates. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 1982, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, L.I.; Sweet, J.; Butt, Z.; Lai, J.S.; Cella, D. Measuring Patient Self-Reported Cognitive Function: Development of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Cognitive Function Instrument. J. Support. Oncol. 2009, 7, W32–W39. [Google Scholar]

- Reitan, R.M. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1958, 8, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, A.M.; Benedict, R.H.; Schretlen, D.; Brandt, J. Construct and concurrent validity of the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-revised. Clin. Neuropsychol. 1999, 13, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, T.W.; James, M.; Owen, A.M.; Sahakian, B.J.; Lawrence, A.D.; McInnes, L.; Rabbitt, P.M. A study of performance on tests from the CANTAB battery sensitive to frontal lobe dysfunction in a large sample of normal volunteers: Implications for theories of executive functioning and cognitive aging. Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 1998, 4, 474–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henneghan, A.M.; Van Dyk, K.; Zhou, X.; Moore, R.C.; Root, J.C.; Ahles, T.A.; Nakamura, Z.M.; Mandeblatt, J.; Ganz, P.A. Validating the PROMIS cognitive function short form in cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2023, 201, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittich, W.; Phillips, N.; Nasreddine, Z.S.; Chertkow, H. Sensitivity and Specificity of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Modified for Individuals who are Visually Impaired. J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 2010, 104, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, D.; Jauregi-Zinkunegi, A.; Betthauser, T.; Carlsson, C.; Bendlin, B.B.; Okonkwo, O.; Chin, N.A.; Asthana, S.; Langhough, R.E.; Johnson, S.C.; et al. Story recall performance and AT classification via positron emission tomography: A comparison of logical memory and Craft Story 21. J. Neurol. Sci. 2024, 464, 123148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, H.L.; Benton, A.L. Revised administration and scoring of the digit span test. J. Consult. Psychol. 1957, 21, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricker, J.H.; Axelrod, B.N.; Houtler, B.D. Clinical Validation of the Oral Trail Making Test. Cogn. Behav. Neurol. 1996, 9, 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Benton, A.L.; Hamsher, K.; Sivan, A.B. Multilingual Aphasia Examination; AJA Associates: Kerala, India, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Pezzuti, L.; Rossetti, S. Letter-Number Sequencing, Figure Weights, and Cancellation subtests of WAIS-IV administered to elders. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 104, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, M.; Maruff, P.; Schembri, A.; Cummins, H.; Bird, L.; Rosenich, E.; Lim, Y.Y. Validation of a digit symbol substitution test for use in supervised and unsupervised assessment in mild Alzheimer’s disease. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2022, 44, 768–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler adult intelligence scale – Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV). [Database Record]. APA PsycTests 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, C.; Freshwater, S.M.; Golden, Z. Stroop Color and Word Test; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Giesinger, J.M.; Loth, F.L.C.; Aaronson, N.K.; Arraras, J.I.; Caocci, G.; Efficace, F.; Groenvold, M.; van Leeuwen, M.; Petersen, M.A.; Ramage, J.; et al. Thresholds for clinical importance were established to improve interpretation of the EORTC QLQ-C30 in clinical practice and research. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 118, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Poll-Franse, L.V.; Mols, F.; Gundy, C.M.; Creutzberg, C.L.; Nout, R.A.; Verdonck-de Leeuw, I.M.; Taphoorn, M.J.; Aaronson, N.K. Normative data for the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC-sexuality items in the general Dutch population. Eur. J. Cancer 2011, 47, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, M.; Clarisse, B.; Leconte, A.; Dembélé, K.P.; Lequesne, J.; Nicola, C.; Dubois, M.; Derues, L.; Gidron, Y.; Castel, H.; et al. Cognitive assessment in patients treated by immunotherapy: The prospective Cog-Immuno trial. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möhn, N.; Sühs, K.W.; Angela, Y.; Stangel, M.; Ivanyi, P.; Beutel, G.; Gutzmer, R.; Skripuletz, T.; Grimmelmann, I. Checkpoint inhibitor–induced autoimmune central nervous system disorder in patients with metastatic melanoma and Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Clin. Exp. Neuroimmunol. 2021, 12, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bir Yucel, K.; Sutcuoglu, O.; Yazıcı, O.; Yıldız, Y.; Şenol, E.; Uner, A. Nivolumab–ipilimumab combination therapy-induced seronegative encephalitis; rapid response to steroid plus intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) treatment. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2023, 29, 760–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; White, W.; Dasanu, C.A. Unusual encephalopathy with Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome-like features due to adjuvant nivolumab for malignant melanoma. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2024, 30, 408–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, M.; Jaffer, M.; Verma, N.; Mokhtari, S.; Ramsakal, A.; Peguero, E. Immune checkpoint inhibitor induced anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 (Anti-GAD 65) limbic encephalitis responsive to intravenous immunoglobulin and plasma exchange. J. Neurol. 2020, 267, 1023–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piepgras, J.; Müller, A.; Steffen, F.; Lotz, J.; Loquai, C.; Zipp, F.; Dresel, C.; Bittner, S. Neurofilament light chain levels reflect outcome in a patient with glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 antibody–positive autoimmune encephalitis under immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Eur. J. Neurol. 2021, 28, 1086–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Xie, X.; Zhang, T.; Yang, M.; Zhou, D.; Yang, T. Anti-GAD65 Antibody-Associated Autoimmune Encephalitis With Predominant Cerebellar Involvement Following Toripalimab Treatment: A Case Report of a Novel irAE of Toripalimab. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 850540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voskens, C.J.; Goldinger, S.M.; Loquai, C.; Robert, C.; Kaehler, K.C.; Berking, C.; Bergmann, T.; Bockmeyer, C.L.; Eigentler, T.; Fluck, M.; et al. The Price of Tumor Control: An Analysis of Rare Side Effects of Anti-CTLA-4 Therapy in Metastatic Melanoma from the Ipilimumab Network. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonk, E.E.; Snijders, T.T.; Koldenhof, J.J.; van Lindert, A.A.; Suijkerbuijk, K.K. Cerebrospinal fluid lymphocytosis: A hallmark of neurological complications during checkpoint inhibition. Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 121, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fu, Z.; Yan, C. Cytokine release syndrome induced by pembrolizumab: A case report. Medicine 2022, 101, e31998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshuma, N.; Glynn, N.; Evanson, J.; Powles, T.; Drake, W.M. Hypothalamitis and severe hypothalamic dysfunction associated with anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 antibody treatment. Eur. J. Cancer 2018, 104, 247–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamnvik, O.P.; Larsen, P.R.; Marqusee, E. Thyroid dysfunction from antineoplastic agents. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2011, 103, 1572–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Peng, S.; Lin, A.; Jiang, A.; Peng, Y.; Gu, T.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, Q.; Zhang, J.; Luo, P. Psychiatric disorders associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A pharmacovigilance analysis of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 59, 101967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Heo, J.Y.; Kim, M.; Lee, S.; Seo, S.; Myung, J.; Oh, J.S.; Park, S.R. Detection and evaluation of signals for immune-related adverse events: A nationwide, population-based study. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1295923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wefel, J.S.; Vardy, J.; Ahles, T.; Schagen, S.B. International Cognition and Cancer Task Force recommendations to harmonise studies of cognitive function in patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson-Carroll, N.; Whisenant, M.; Crane, S.; Johnson, C. Impact of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy on Quality of Life in Patients With Advanced Melanoma: A Systematic Review. Cancer Nurs. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutros, A.; Bruzzone, M.; Tanda, E.T.; Croce, E.; Arecco, L.; Cecchi, F.; Pronzato, P.; Ceppi, M.; Lambertini, M.; Spagnolo, F. Health-related quality of life in cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors in randomised controlled trials: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 159, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, J.; Page, D.B.; Li, B.T.; Connell, L.C.; Schindler, K.; Lacouture, M.E.; Postow, M.A.; Wolchok, J.D. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 2375–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuzzubbo, S.; Javeri, F.; Tissier, M.; Roumi, A.; Barlog, C.; Doridam, J.; Lebbe, C.; Belin, C.; Ursu, R.; Carpentier, A.F. Neurological adverse events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: Review of the literature. Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 73, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utne, I.; Løyland, B.; Grov, E.K.; Paul, S.; Wong, M.L.; Conley, Y.P.; Cooper, B.A.; Levine, J.D.; Miaskowski, C. Co-occuring symptoms in older oncology patients with distinct attentional function profiles. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2019, 41, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Participants | Cognitive Function Assessments | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cuzzubbo et al., 2018 [27] France | n = 15 Median age-66 yr (range 33–86 yr) Female-8 Male-7 Melanoma-8 Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)-7 Nivolumab-10 Pembrolizumab-4 Ipilimumab-1 | Longitudinal study (assessments at baseline, 3 months) Montreal Cognitive Assessment/MoCA (evaluates executive function, visuo-spatial, short-term memory, working memory, language, attention, orientation) [37] “Abnormal” = score < 26/30 Test des neuf images-93/TNI-93 (episodic memory) [38] “Abnormal” = score < 6 free recall or <9 total recall | Baseline (n = 15): Abnormal MoCA—9 (60%) participants Abnormal TNI-93—5 (33.5%) participants “Abnormal cognitive functions were associated with previous treatment with cytotoxic chemotherapy… and lung cancer” 3 months (n = 9): Abnormal MoCA—6 (67%) participants (5 had abnormal MoCA at baseline) Abnormal TNI-93—3 (33%) participants (2 had abnormal TNI-93 at baseline) “MoCA and TNI-93 scores were globally stable in the majority of patients” |

| Rogiers et al., 2020a [28] Belgium | n = 25 Median age-58 yr (range 26–86 yr) Female-18 Male-7 Melanoma-25 Pembrolizumab-25 (12 on treatment, 13 post-treatment at baseline) “Metastatic melanoma survivors” “Melanoma patients with unresectable AJCC stage III or IV disease were eligible… if they were on pembrolizumab treatment for at least 6 months and free from progression at their latest follow-up” | Longitudinal study (assessments at baseline, 3–4 months, 5–7 months, 8–9 months, 10–12 months) EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire-C30/EORTC QLQ-C30 cognitive functioning scale [39] Cogstate computerized battery of tests [40]: Detection test (processing speed); Identification test (attention); International Shopping List (verbal memory); delayed International Shopping List (verbal memory); One Back test (working memory); Groton Maze Learning Task (executive function) “Impairment on a single test was classified when performance was lower than 1 standard deviation below normal age-appropriate mean” “Cognitive impairment was classified when abnormal performance occurred on at least 3 tests… in the battery” | Baseline (n = 25): EORTC QLQ-C30 cognitive functioning scale—mean 75.0 (SD +/− 18.0) [Statistically significantly different from European reference values: p = 0.00025; European mean—90.5 (SD +/− 15.7) [41]] Cognitive impairment (Cogstate battery)—5 (20%) participants 3–4 months (n = 18): Cognitive impairment (Cogstate battery)—2 (11%) participants 5–7 months (n = 24): EORTC QLQ-C30 cognitive functioning scale—mean 76.4 (SD +/− 21.5) [Statistically significantly different from European reference values: p = 0.02] Cognitive impairment (Cogstate battery)—3 (13%) participants 8–9 months (n = 6): Cognitive impairment (Cogstate battery)—0 (0%) participants 10–12 months (n = 24): EORTC QLQ-C30 cognitive functioning scale—mean 79.9 (SD +/− 16.7) [Statistically significantly different from European reference values: p = 0.005] Cognitive impairment (Cogstate battery)—5 (21%) participants “Performance was relatively stable across the five assessment timepoints… across each neurocognitive composite” “No significant correlations were found between memory, processing speed and executive function and… subjective cognitive function (EORTC QLQ-C30)” |

| Rogiers et al., 2020b [29] Belgium | n = 17 Median age-63.4 yr (range 42–85 yr) Female-12 Male-5 Melanoma-17 Ipilimumab-17 (17 post-treatment at baseline) “Metastatic melanoma survivors” “Eligible patients… unresect-able stage III or IV melanoma; survivors were disease-free for at least 2 years following start of IPI” | Longitudinal study (assessments at baseline, 12 months) EORTC QLQ-C30 cognitive functioning scale [39] Cognitive Failures Questionnaire/CFQ [42] “Impairment” = score ≥ 44 Cogstate computerized battery of tests [40]: Detection test (processing speed); Identification test (attention); International Shopping List (verbal memory); delayed International Shopping List (verbal memory); One Back test (working memory); Groton Maze Learning Task (executive function) “Impairment on a single test was classified when performance was lower than 1 standard deviation below normal age-appropriate mean” “Impairment in NCF (neurocognitive function)… was classified when abnormal performance occurred on at least 3 tests… in the battery” | Baseline (n = 17): EORTC QLQ-C30 cognitive functioning scale—mean 72.6 (SD +/− 27.6). [Not statistically significantly different from European reference values: p = 0.09; European mean—84.8 (SD +/− 21.3) [41]] Impairment CFQ—7 (41%) participants Impairment NCF (Cogstate battery)—7 (44%) participants (n = 16) 12 months (n = 15): EORTC QLQ-C30 cognitive functioning scale—mean 64.4 (SD +/− 25.9). [Statistically significantly different from European reference values: p = 0.009)] Impairment CFQ—7 (47%) participants Impairment NCF (Cogstate battery)—4 (33%) participants (n = 12) “Only performance on the verbal memory test… was correlated significantly with ratings of… subjective cognition (CFQ)” |

| Boekhout et al., 2021 [30] Belgium/Netherlands | n = 89 Median age-65 yr (range 23–87 yr) Female-38 Male-51 Melanoma-89 Ipilimumab-89 “Advanced melanoma survivors” “Survivors eligible for this study… had survived at least 2 years following last admin-istration of ipilimumab for advanced melanoma… and were not diagnosed with recurrent systemic disease” | Cross-sectional study EORTC QLQ-C30 cognitive functioning scale [39] | EORTC QLQ-C30 cognitive functioning scale—mean 83.7 (SD +/− 21.0) [Statistically significantly different from matched general population values: p = 0.001; matched general population mean—91.9 (SD +/− 14)] “56% reported memory and concentration problems” (data from Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Melanoma/FACT-M questionnaire) |

| Invitto et al., 2022 [31] Italy | n = 43 Mean age-78 yr (SD +/−5.6) Female-10 Male-33 Cancer diagnosis-not stated Immunotherapy-not stated Control groups: “Oncogeriatric” chemo-therapy patients (n = 70) “Geriatric control” subjects (n = 41) | Cross-sectional study Mini-Mental State Examination/MMSE (spatial orientation, temporal orientation, memory skills, attention, calculus, language, constructive praxis) [43] “Impairments” = < 22/30 | Immunotherapy group—mean MMSE score 23.942 (SD +/− 3.375) Chemotherapy group—mean MMSE score 24.276 (SD +/− 3.253) Geriatric controls group—mean MMSE score 25.127 (SD +/− 2.918) “No differences related to the type of therapy emerged from MMSE” |

| Ma et al., 2023 [32] China Subjective data | n = 292 (matched patients) Median age-62 yr (range 52–68 yr) Female-103 Male-189 NSCLC-292 Immunotherapy—not determinable Control group—matched NSCLC patients not scheduled to receive immunotherapy | Longitudinal study (assessments at baseline, 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, 12 months, 15 months) Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Cognitive Function/FACT-Cog [44] “Perceived cognitive decline events” (PCDE) = change in perceived cognitive impairment (PCI) subscore of > 0.5 SD mean baseline scores | Baseline (n = 292 matched pairs): Mean PCI subscore—65.54 (SD +/− 11.49) immunotherapy group; 65.60 (SD +/− 9.34) control group 3 months (n = 292): PCDE—23 immunotherapy group; 1 control group (p < 0.001) 6 months (n = 292): PCDE—31 immunotherapy group; 3 control group (p < 0.001) 9 months (n = 292): PCDE—47 immunotherapy group; 8 control group (p < 0.001) 12 months (n = 292): PCDE—70 immunotherapy group; 7 control group (p < 0.001) 15 months (n = 292): PCDE—66 immunotherapy group; 9 control group (p < 0.001) “Patients aged >65 years had significantly higher PCI score changes than patients aged ≤65 years (p < 0.01 for all sessions… )” “There were significant differences in (PCI) score changes… suggesting an increased level of cognitive decline as treatment progressed” “There was a poor correlation between the outcomes of perceived cognitive impairment and objective neurocognitive test” |

| Ma et al., 2023 [32] China Objective data | n = 240 (matched patients) Mean age-61.08 yr (SD +/− 10.63) Female-86 Male-154 NSCLC-240 Nivolumab-113 Pembrolizumab-90 Durvalumab-37 Control group—matched NSCLC patients not scheduled to receive immunotherapy | Longitudinal study (assessments at baseline, 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, 12 months, 15 months) Trail Making Test/TMT A [45] Immediate Hopkins Verbal Learning Test—Revised/HVLTi [46] Delayed Hopkins Verbal Learning Test—Revised/HVLTd [46] Stockings of Cambridge [47] Objective Cognitive Impairment (OCI) = “two test score changes ≥ 1.5 SD from baseline scores, or one test score ≥2 SD from baseline score” Cognitive Adverse Event (CoAE) = “any NBT (neuropsychological battery test) score changes at each session that exceeded 3*SD of baseline scores” | Baseline (n = 240 matched pairs): OCI—28 (11.7%) immunotherapy group; 36 (15%) control group 6 months (n = 240): CoAE—82 (34.2%) immunotherapy group; 16 (6.7%) control group 12 months (n = 240): CoAE—102 (42.5%) immunotherapy group; 56 (23.3%) control group “Objective deficits were observed in the 12 month in matched protocol TMT studies” (but not other NBT scores) “No significant difference… by age in NBT score changes” |

| Myers et al., 2023 [33] United States America | n = 20 Median age-73.5 yr (range 32–88 yr) Female-8 Male-12 Melanoma-12 Other-8 Pembrolizumab-7 Nivolumab-6 Other-6 | Longitudinal study (assessments at baseline, 6 months) Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Cognitive Function 8a [48]; PROMIS Cognitive Abilities 8a [48] MoCA/MoCA-Blind * (see above) [37,49] Craft story 21 Recall (episodic memory) [50] Digit span forward and backward (working memory) [51] TMT A/Oral TMT A * (processing speed) [52] TMT B/Oral TMT B * (executive function) [52] Verbal fluency (F and L) [53] Category fluency (animals and vegetables) [53] Letter number sequencing (working memory) [54] (Digit symbol) ** [55] (Block design) ** [56] (Stroop test) ** [57] | Baseline (n = 20): PROMIS Cognitive Function 8a mean T-Score 51.08 (SD +/− 8.86) PROMIS Cognitive Abilities 8a mean T-Score 54.51 (SD +/− 9.85) Estimated difference in MoCA-Blind score versus control data from “cognitively intact” persons −1.735 [95% CI: −3.591 to 0.122; p = 0.066] 6 months (n = 13): PROMIS Cognitive Function 8a mean T-Score 47.65 (SD +/− 8.07) PROMIS Cognitive Abilities 8a mean T-Score 51.62 (SD +/− 6.91) Change in PROMIS Cognitive Function 8a T score, and PROMIS Cognitive Abilities 8a mean T-Score, was not statistically significant Estimated difference in MoCA-Blind score versus control data from “cognitively intact” persons = −2.465 [95% CI: −4.304 to −0.627; p = 0.011] “No significant within-group changes were noted for the CPI (check point inhibitor) group participants’ performances on the neurocognitive tests” |

| Rogiers et al., 2023 [34] Belgium/Luxembourg | n = 125 (prospectively enrolled patients) Median age-60 yr (range 29–85 yr) Female-72 Male-80 Melanoma-152 Nivolumab-152 | Longitudinal study (assessments at baseline, 9 months, 18 months—6 months post-therapy) EORTC QLQ-C30 cognitive functioning scale [39] “Threshold for clinical importance” (TCI) = score < 75 [58] | Baseline (n = 125): EORTC QLQ-C30 cognitive functioning scale—mean 89.6 (SD +/− 19.7) [Not statistically significantly different from European reference values; European mean—84.8 (SD +/− 21.3) [41]] 17% patients score < TCI (n = 123) 3 months: 28% patients score < TCI (n = 95) 18 months: 34% patients score < TCI (n = 59) “Although cognitive functioning mean scores remained stable, they decreased (deteriorated) and approached prespecified thresholds for MIDs (minimally important differences)” |

| Suazo-Zepeda et al., 2023 [35] Netherlands | n = 151 Mean age-65.8 yr (SD +/− 9.25) Female-52 Male-99 NSCLC-151 Immunotherapy-not stated | Longitudinal study (assessments at baseline, 6 months) EORTC QLQ-C30 cognitive functioning scale [39] | Baseline: EORTC QLQ-C30 cognitive functioning scale <59 yr—mean 80.27 [Statistically significantly different from normative population value: p < 0.05; normative population mean—92.02 [59] EORTC QLQ-C30 cognitive functioning scale 60–69 yr—mean 86.11 [Statistically significantly different from normative population value: p < 0.05; normative population mean—92.90] EORTC QLQ-C30 cognitive functioning scale ≥70 yr—mean 88.71 [Not statistically significantly different from normative population value; normative population mean—90.10] 6 months: EORTC QLQ-C30 cognitive functioning scale <59 yr—mean 85.76 [Statistically significantly different from normative population value: p < 0.05] EORTC QLQ-C30 cognitive functioning scale 60–69 yr—mean 85.76 [Statistically significantly different from normative population value: p < 0.05] EORTC QLQ-C30 cognitive functioning scale ≥70 yr—mean 79.74 [Statistically significantly different from normative population value: p < 0.05] “Older age (per 10-year increment) was negatively associated with change in… cognitive functioning” |

| Vanlaer et al., 2024 [36] Belgium | n = 70 Median age-65 yr (range 34–92 yr) Female-28 Male-42 Melanoma-57 NSCLC-7 Other-6 Pembrolizumab-36 Ipilimumab/Nivolumab-13 Nivolumab-9 Ipilimumab-5 Ipilimumab/dendritic cell therapy-5 Other-2 “Advanced cancer survivors” “Patients diagnosed with unresectable stage III/IV cancer of any type, who initiated ICB (Immune Checkpoint Blockade) at least one year prior… and who had a complete metabolic remission” | Cross-sectional study Semi-structured interview CFQ [42] “Moderate subjective cognitive complaints” = score ≥ 44 “Severe subjective cognitive complaints” = score ≥ 55 | Interview—”thirty patients (42.9%) reported having memory and/or concentration problems that impacted on their daily life activities” (see text for further details) Moderate cognitive complaints CFQ—7 (10%) participants Severe cognitive complaints CFQ—6 (8.5%) participants Cognitive complaints were not correlated with age |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hearne, S.; McDonnell, M.; Lavan, A.H.; Davies, A. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Cognition in Adults with Cancer: A Scoping Review. Cancers 2025, 17, 928. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17060928

Hearne S, McDonnell M, Lavan AH, Davies A. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Cognition in Adults with Cancer: A Scoping Review. Cancers. 2025; 17(6):928. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17060928

Chicago/Turabian StyleHearne, Síofra, Muireann McDonnell, Amanda Hanora Lavan, and Andrew Davies. 2025. "Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Cognition in Adults with Cancer: A Scoping Review" Cancers 17, no. 6: 928. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17060928

APA StyleHearne, S., McDonnell, M., Lavan, A. H., & Davies, A. (2025). Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Cognition in Adults with Cancer: A Scoping Review. Cancers, 17(6), 928. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17060928