The Dual Effects of CDK4/6 Inhibitors on Tumor Immunity

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

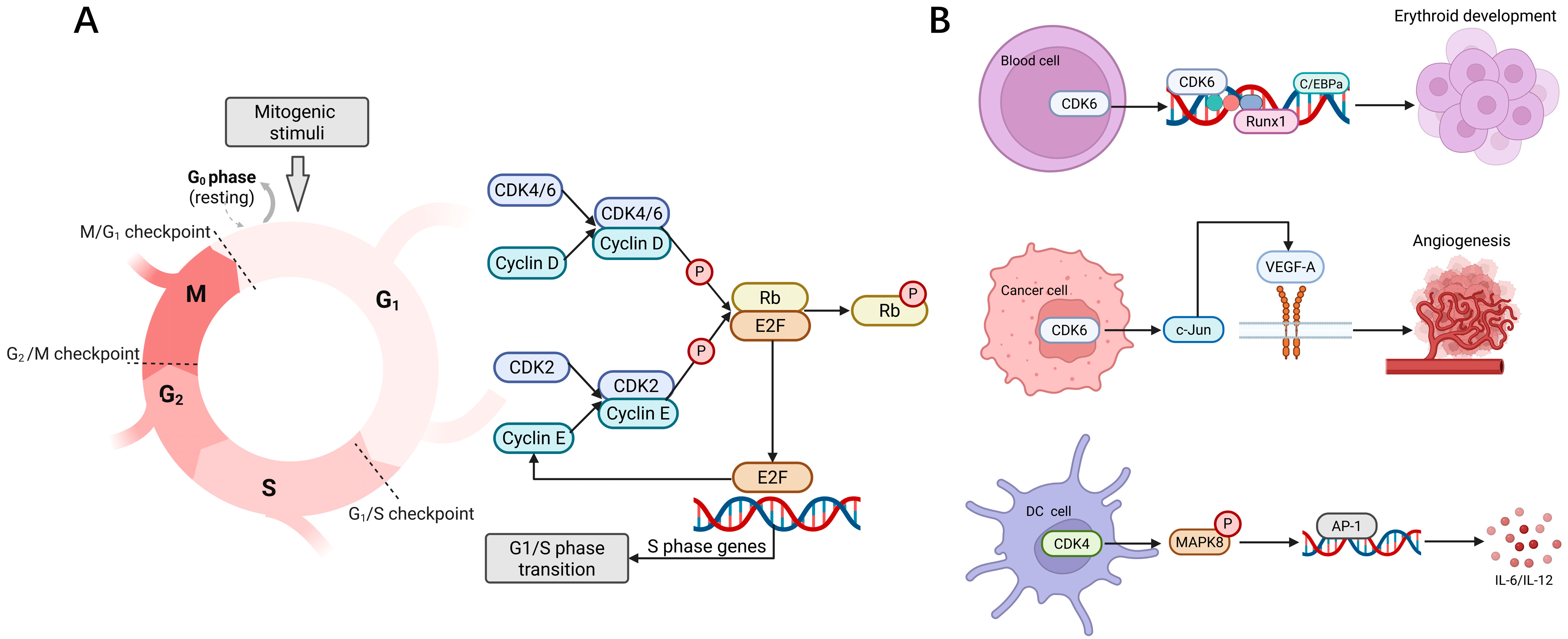

2. Role of CDK4/6 in Biology

3. Activating Anti-Tumor Immunity via CDK4/6is

3.1. Enhancing Antigen Processing and Presentation in Tumor Cells

3.2. Mediating the Release of the Immunostimulatory Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype by Tumor Cells

3.3. Inducing Tumor Cells to Undergo Immunogenic Cell Death

3.4. Increasing T Cell Infiltration and Activation

3.5. Decreasing Immunosuppressive Cells

3.6. Enhancing the Infiltration and Function of Antigen-Presenting Cells

3.7. Inducing T Cell Memory

3.8. Enhancing NK Cell Surveillance

4. Suppression of Anti-Tumor Immunity via CDK4/6is

4.1. Interferon Pathway Abnormal Activation

4.2. Mediating the Release of the Immunosuppressive SASP by Tumor Cells

4.3. Enhancing the Expression of PD-L1 in Tumor Cells Mediates Immune Escape

4.4. Inducing Unexpected Alterations in Immune Cells Within the Tumor Microenvironment

5. Clinical Trials for the Combination of CDK4/6is and Immunotherapy

6. Raising Discussions and Perspectives

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Frank, D.A. Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 4/6 Inhibitors: Is a Noncanonical Substrate the Key Target? Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 1170–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, S.; Bergholz, J.S.; Zhao, J.J. Targeting CDK4 and CDK6 in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2022, 22, 356–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Leone, G.W.; Wang, H. Cyclin D-CDK4/6 functions in cancer. Adv. Cancer Res. 2020, 148, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmalak, M.; Singh, R.; Anwer, M.; Ivanchenko, P.; Randhawa, A.; Ahmed, M.; Ashton, A.W.; Du, Y.; Jiao, X.; Pestell, R. The Renaissance of CDK Inhibitors in Breast Cancer Therapy: An Update on Clinical Trials and Therapy Resistance. Cancers 2022, 14, 5388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riess, C.; Irmscher, N.; Salewski, I.; Strüder, D.; Classen, C.-F.; Große-Thie, C.; Junghanss, C.; Maletzki, C. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors in head and neck cancer and glioblastoma—backbone or add-on in immune-oncology? Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2021, 40, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, M.R.; Jhaveri, K.; Kalinsky, K.; Bardia, A.; Wander, S.A. Precision therapeutics and emerging strategies for HR-positive metastatic breast cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 21, 743–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhillon, S. Trilaciclib: First Approval. Drugs 2021, 81, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, J.; Balaji, U.; Freinkman, E.; Witkiewicz, A.K.; Knudsen, E.S. Metabolic Reprogramming of Pancreatic Cancer Mediated by CDK4/6 Inhibition Elicits Unique Vulnerabilities. Cell Rep. 2016, 14, 979–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourdeau, V.; Ferbeyre, G. CDK4-CDK6 inhibitors induce autophagy-mediated degradation of DNMT1 and facilitate the senescence antitumor response. Autophagy 2016, 12, 1965–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Ma, B.; Ruscetti, M. Cellular senescence offers distinct immunological vulnerabilities in cancer. Trends Cancer 2025, 11, 334–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Park, S.; Li, Y. Breaking Cancer’s Momentum: CDK4/6 Inhibitors and the Promise of Combination Therapy. Cancers 2025, 17, 1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassl, A.; Geng, Y.; Sicinski, P. CDK4 and CDK6 kinases: From basic science to cancer therapy. Science 2022, 375, eabc1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Ge, S.; Xie, Y.; Sun, R.; Wu, Y.; Xu, J. The regulatory role of CDK4/6 inhibitors in tumor immunity and the potential value of tumor immunotherapy (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2025, 56, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xu, Q.; Sun, W.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, J. Immunomodulatory effects of CDK4/6 inhibitors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Rev. Cancer 2023, 1878, 188912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laphanuwat, P.; Jirawatnotai, S. Immunomodulatory Roles of Cell Cycle Regulators. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, D.; Huang, R.; Ning, S. Breaking through therapeutic barriers: Insights into CDK4/6 inhibition resistance in hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Rev. Cancer 2024, 1879, 189174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, S.; DeCristo, M.J.; McAllister, S.S.; Zhao, J.J. CDK4/6 Inhibition in Cancer: Beyond Cell Cycle Arrest. Trends Cell Biol. 2018, 28, 911–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, R.A. The retinoblastoma protein and cell cycle control. Cell 1995, 81, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, B.; Finn, R.S.; Turner, N.C. Treating cancer with selective CDK4/6 inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 13, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, L.; Loibl, S.; Turner, N.C. The CDK4/6 inhibitor revolution—A game-changing era for breast cancer treatment. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 21, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Feng, Y.; Shen, J.; Hornicek, F.J.; Duan, Z. The roles and therapeutic potential of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) in sarcoma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2016, 35, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimoto, T.; Anderson, K.; Jacobsen, S.E.W.; Nishikawa, S.I.; Nerlov, C. Cdk6 blocks myeloid differentiation by interfering with Runx1 DNA binding and Runx1-C/EBPα interaction. EMBO J. 2007, 26, 2361–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurer, B.; Brandstoetter, T.; Kollmann, S.; Sexl, V.; Prchal-Murphy, M. Inducible deletion of CDK4 and CDK6—Deciphering CDK4/6 inhibitor effects in the hematopoietic system. Haematologica 2021, 106, 2624–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Li, Z.; Bhatt, T.; Dickler, M.; Giri, D.; Scaltriti, M.; Baselga, J.; Rosen, N.; Chandarlapaty, S. Acquired CDK6 amplification promotes breast cancer resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors and loss of ER signaling and dependence. Oncogene 2017, 36, 2255–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanden Bush, T.J.; Bishop, G.A. CDK-mediated regulation of cell functions via c-Jun phosphorylation and AP-1 activation. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.G.; Deshpande, A.; Enos, M.; Mao, D.; Hinds, E.A.; Hu, G.-f.; Chang, R.; Guo, Z.; Dose, M.; Mao, C.; et al. A requirement for cyclin-dependent kinase 6 in thymocyte development and tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 810–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amulic, B.; Knackstedt, S.L.; Abu Abed, U.; Deigendesch, N.; Harbort, C.J.; Caffrey, B.E.; Brinkmann, V.; Heppner, F.L.; Hinds, P.W.; Zychlinsky, A. Cell-Cycle Proteins Control Production of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps. Dev. Cell 2017, 43, 449–462.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Halima, A.; Chan, T.A. Antigen presentation in cancer—Mechanisms and clinical implications for immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 20, 604–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopfer, L.E.; Mesfin, J.M.; Joughin, B.A.; Lauffenburger, D.A.; White, F.M. Multiplexed relative and absolute quantitative immunopeptidomics reveals MHC I repertoire alterations induced by CDK4/6 inhibition. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, S.; DeCristo, M.J.; Watt, A.C.; BrinJones, H.; Sceneay, J.; Li, B.B.; Khan, N.; Ubellacker, J.M.; Xie, S.; Metzger-Filho, O.; et al. CDK4/6 inhibition triggers anti-tumour immunity. Nature 2017, 548, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, A.C.; Cejas, P.; DeCristo, M.J.; Metzger-Filho, O.; Lam, E.Y.N.; Qiu, X.; BrinJones, H.; Kesten, N.; Coulson, R.; Font-Tello, A.; et al. CDK4/6 inhibition reprograms the breast cancer enhancer landscape by stimulating AP-1 transcriptional activity. Nat. Cancer 2021, 2, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Huang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Zhou, J.; Qin, X.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Guo, E.; Yang, B.; et al. The Immunological Role of CDK4/6 and Potential Mechanism Exploration in Ovarian Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 799171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Liu, W.; Zeng, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, M.; Yang, L.; Liu, H.; Shi, Y.; Li, L.; Ma, J.; et al. DNA damage induced by CDK4 and CDK6 blockade triggers anti-tumor immune responses through cGAS-STING pathway. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Guo, F.; Zeng, R.; Liang, H.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, W.; Wu, H.; Yang, C.; Jin, X. CDK4/6 Alters TBK1 Phosphorylation to Inhibit the STING Signaling Pathway in Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 2588–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, J.; O’Connor, T.N.; Tzetzo, S.L.; Gurova, K.V.; Knudsen, E.S.; Witkiewicz, A.K. Separable Cell Cycle Arrest and Immune Response Elicited through Pharmacological CDK4/6 and MEK Inhibition in RASmut Disease Models. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2024, 23, 1801–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Fan, Z.; Zeng, A.; Wang, A.; Pan, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, H.; Chen, W.; Nie, D.; Lin, J.; et al. Biomimetic Targeted Co-Delivery System Engineered from Genomic Insights for Precision Treatment of Osteosarcoma. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2410427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, V.; Gil, J. Senescence as a therapeutically relevant response to CDK4/6 inhibitors. Oncogene 2020, 39, 5165–5176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorgoulis, V.; Adams, P.D.; Alimonti, A.; Bennett, D.C.; Bischof, O.; Bishop, C.; Campisi, J.; Collado, M.; Evangelou, K.; Ferbeyre, G.; et al. Cellular Senescence: Defining a Path Forward. Cell 2019, 179, 813–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wekking, D.; Leoni, V.P.; Lambertini, M.; Dessì, M.; Pretta, A.; Cadoni, A.; Atzori, L.; Scartozzi, M.; Solinas, C. CDK4/6 inhibition in hormone receptor-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer: Biological and clinical aspects. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 2024, 75, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, I.; Boix, O.; Garcia-Garijo, A.; Sirois, I.; Caballe, A.; Zarzuela, E.; Ruano, I.; Attolini, C.S.-O.; Prats, N.; López-Domínguez, J.A.; et al. Cellular Senescence Is Immunogenic and Promotes Antitumor Immunity. Cancer Discov. 2023, 13, 410–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderick, C.; Mezzadra, R.; Sisso, E.M.; Mbuga, F.; Raghulan, R.; Chaves Perez, A.; Kulick, A.; Jiang, L.; Jiang, J.; Ho, Y.-J.; et al. A RAS(ON) multi-selective inhibitor combination therapy triggers long-term tumor control through senescence-associated tumor-immune equilibrium in PDAC. Cancer Discov. 2025, 15, 1717–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favaretto, G.; Rossi, M.N.; Cuollo, L.; Laffranchi, M.; Cervelli, M.; Soriani, A.; Sozzani, S.; Santoni, A.; Antonangeli, F. Neutrophil-activating secretome characterizes palbociclib-induced senescence of breast cancer cells. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2024, 73, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Yin, G.; Chen, S.; Tacke, F.; Guillot, A.; Liu, H. CDK4/6 inhibition enhances T-cell immunotherapy on hepatocellular carcinoma cells by rejuvenating immunogenicity. Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.-F.; Li, J.; Jiang, K.; Wang, R.; Ge, J.-L.; Yang, H.; Liu, S.-J.; Jia, L.-T.; Wang, L.; Chen, B.-L. CDK4/6 inhibition promotes immune infiltration in ovarian cancer and synergizes with PD-1 blockade in a B cell-dependent manner. Theranostics 2020, 10, 10619–10633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Imran, M.; Choi, J.H.; Park, Y.J.; Kim, Y.H.; Min, S.; Park, T.J.; Choi, Y.W. CDK4/6 inhibitors induce breast cancer senescence with enhanced anti-tumor immunogenic properties compared with DNA-damaging agents. Mol. Oncol. 2024, 18, 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Varela-Eirin, M.; Brandenburg, S.M.; Hernandez-Segura, A.; van Vliet, T.; Jongbloed, E.M.; Wilting, S.M.; Ohtani, N.; Jager, A.; Demaria, M. Pharmacological CDK4/6 inhibition reveals a p53-dependent senescent state with restricted toxicity. EMBO J. 2022, 41, e108946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruscetti, M.; Leibold, J.; Bott, M.J.; Fennell, M.; Kulick, A.; Salgado, N.R.; Chen, C.-C.; Ho, Y.-J.; Sanchez-Rivera, F.J.; Feucht, J.; et al. NK cell–mediated cytotoxicity contributes to tumor control by a cytostatic drug combination. Science 2018, 362, 1416–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chibaya, L.; DeMarco, K.D.; Lusi, C.F.; Kane, G.I.; Brassil, M.L.; Parikh, C.N.; Murphy, K.C.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Li, J.; Ma, B.; et al. Nanoparticle delivery of innate immune agonists combined with senescence-inducing agents promotes T cell control of pancreatic cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2024, 16, eadj9366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, A.M.; Lopez, M.A.; Rosenberger, M.G.; Kim, J.Y.; Shen, J.; Chen, Q.; Ung, T.; Ibeh, U.M.; Knight, H.R.; Rutledge, N.S.; et al. Identification of CDK4/6 Inhibitors as Small Molecule NLRP3 Inflammasome Activators that Facilitate IL-1β Secretion and T Cell Adjuvanticity. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 14974–14985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Chen, W.; Sun, S.; Lu, Y.; Wu, G.; Xu, H.; Yang, H.; Li, C.; He, W.; Xu, M.; et al. CDK4/6 inhibitor PD-0332991 suppresses hepatocarcinogenesis by inducing senescence of hepatic tumor-initiating cells. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 73, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fucikova, J.; Kepp, O.; Kasikova, L.; Petroni, G.; Yamazaki, T.; Liu, P.; Zhao, L.; Spisek, R.; Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L. Detection of immunogenic cell death and its relevance for cancer therapy. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Shi, J.; Du, G. Mesoporous polydopamine Targeting CDK4/6 Inhibitor toward Brilliant Synergistic Immunotherapy of Breast Cancer. Small 2024, 20, e2310565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Liang, J.; Fan, J.; Hou, P.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, K.; Bu, L.; Li, P.; He, M.; et al. CDK4/6 Inhibition Enhances Oncolytic Virus Efficacy by Potentiating Tumor-Selective Cell Killing and T-cell Activation in Refractory Glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 3359–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, J.; Tan, X.; Song, X.; Gao, M.; Risnik, D.; Hao, S.; Ermine, K.; Wang, P.; Li, H.; Huang, Y.; et al. CDK4/6 Inhibition Suppresses p73 Phosphorylation and Activates DR5 to Potentiate Chemotherapy and Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 1340–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Yang, M.; Zou, H.; Shen, S.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, D.; Ding, J. Poly(amino acid) nanoformulation of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and 6 inhibitor for molecularly targeted immunotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer. J. Control. Release 2025, 380, 760–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lian, Y.; Zhou, C.; Cheng, J.; Zhao, S.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Lu, X.; Shi, J.; Du, G. Self-assembled natural triterpenoids for the delivery of cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors to enhance cancer chemoimmunotherapy. J. Control. Release 2025, 378, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, Z.L.; Versaci, S.; Dushyanthen, S.; Caramia, F.; Savas, P.; Mintoff, C.P.; Zethoven, M.; Virassamy, B.; Luen, S.J.; McArthur, G.A.; et al. Combined CDK4/6 and PI3Kα Inhibition Is Synergistic and Immunogenic in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 6340–6352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaer, D.A.; Beckmann, R.P.; Dempsey, J.A.; Huber, L.; Forest, A.; Amaladas, N.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.C.; Rasmussen, E.R.; Chin, D.; et al. The CDK4/6 Inhibitor Abemaciclib Induces a T Cell Inflamed Tumor Microenvironment and Enhances the Efficacy of PD-L1 Checkpoint Blockade. Cell Rep. 2018, 22, 2978–2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleman, L.J.; Berezovskaya, A.; Grass, I.; Boussiotis, V.A. CD28 costimulation mediates T cell expansion via IL-2-independent and IL-2-dependent regulation of cell cycle progression. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, A.D.; Morawski, P.A. New roles for cyclin-dependent kinases in T cell biology: Linking cell division and differentiation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, A.; Rosen, L.S.; Tolaney, S.M.; Tolcher, A.W.; Goldman, J.W.; Gandhi, L.; Papadopoulos, K.P.; Beeram, M.; Rasco, D.W.; Hilton, J.F.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Abemaciclib, an Inhibitor of CDK4 and CDK6, for Patients with Breast Cancer, Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, and Other Solid Tumors. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 740–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzhachenko, R.V.; Bharti, V.; Ouyang, Z.; Blevins, A.; Mont, S.; Saleh, N.; Lawrence, H.A.; Shen, C.; Chen, S.-C.; Ayers, G.D.; et al. Metabolic modulation by CDK4/6 inhibitor promotes chemokine-mediated recruitment of T cells into mammary tumors. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 108944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Jiang, D.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhao, M.; Shen, Y.; Liao, W.; Yang, H.; Li, J. CDK4/6i enhances the antitumor effect of PD1 antibody by promoting TLS formation in ovarian cancer. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayyar, N.; de Sauvage, M.A.; Chuprin, J.; Sullivan, E.M.; Singh, M.; Torrini, C.; Zhang, B.S.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Daniels, K.A.; Alvarez-Breckenridge, C.; et al. CDK4/6 Inhibition Sensitizes Intracranial Tumors to PD-1 Blockade in Preclinical Models of Brain Metastasis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 420–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Wang, E.S.; Jenkins, R.W.; Li, S.; Dries, R.; Yates, K.; Chhabra, S.; Huang, W.; Liu, H.; Aref, A.R.; et al. CDK4/6 Inhibition Augments Antitumor Immunity by Enhancing T-cell Activation. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 216–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Yang, P.; Mastoraki, S.; Rao, X.; Wang, Y.; Kettner, N.M.; Raghavendra, A.S.; Tripathy, D.; Damodaran, S.; Hunt, K.K.; et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing identifies molecular biomarkers predicting late progression to CDK4/6 inhibition in patients with HR+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teh, J.L.F.; Aplin, A.E. Arrested Developments: CDK4/6 Inhibitor Resistance and Alterations in the Tumor Immune Microenvironment. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.; Guo, Z.-Q.; Zhang, Y.-P.; Fan, Z.-Z.; Liu, L.-J.; Liu, L.; Long, L.-L.; Ma, S.-C.; Wang, J.; Fang, Y.; et al. CDK4/6 inhibition triggers ICAM1-driven immune response and sensitizes LKB1 mutant lung cancer to immunotherapy. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wu, Y.; Kang, K.; Zhang, X.; Luo, R.; Tu, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Lin, G.; Wang, H.; Tang, M.; et al. CDK4/6 inhibitor abemaciclib combined with low-dose radiotherapy enhances the anti-tumor immune response to PD-1 blockade by inflaming the tumor microenvironment in Rb-deficient small cell lung cancer. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2024, 13, 1032–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussiotis, V.A.; Freeman, G.J.; Taylor, P.A.; Berezovskaya, A.; Grass, I.; Blazar, B.R.; Nadler, L.M. p27kip1 functions as an anergy factor inhibiting interleukin 2 transcription and clonal expansion of alloreactive human and mouse helper T lymphocytes. Nat. Med. 2000, 6, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, A.; Krone, P.; Maennicke, J.; Henne, J.; Oehmcke-Hecht, S.; Redwanz, C.; Bergmann-Ewert, W.; Junghanss, C.; Henze, L.; Maletzki, C. Prophylaxis with abemaciclib delays tumorigenesis in dMMR mice by altering immune responses and reducing immunosuppressive extracellular vesicle secretion. Transl. Oncol. 2024, 47, 102053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salewski, I.; Henne, J.; Engster, L.; Krone, P.; Schneider, B.; Redwanz, C.; Lemcke, H.; Henze, L.; Junghanss, C.; Maletzki, C. CDK4/6 blockade provides an alternative approach for treatment of mismatch-repair deficient tumors. Oncoimmunology 2022, 11, 2094583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, A.Y.; Sorrentino, J.A.; Dragnev, K.H.; Weiss, J.M.; Owonikoko, T.K.; Rytlewski, J.A.; Hood, J.; Yang, Z.; Malik, R.K.; Strum, J.C.; et al. CDK4/6 inhibition enhances antitumor efficacy of chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitor combinations in preclinical models and enhances T-cell activation in patients with SCLC receiving chemotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, L.; An, J.; Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Han, X. The combination of IL-2 nanoparticles and Palbociclib enhances the anti-tumor immune response for colon cancer therapy. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1309509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, M.; Yang, L.; Wang, X.; Chen, M.; Zhang, H.; He, B.; Wang, X.; et al. Sequential responsive nano-PROTACs for precise intracellular delivery and enhanced degradation efficacy in colorectal cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Z.; Qin, M.; Jiang, J.; Wang, M.; Zhang, T.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Shi, H.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Iterative Design of a Prodrug Nanocarrier for Cell Cycle Arrest, Immune Modulation, and Enhanced T Cell Infiltration for Colon Cancer Therapy. Nano Lett. 2025, 25, 2820–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scirocchi, F.; Scagnoli, S.; Botticelli, A.; Di Filippo, A.; Napoletano, C.; Zizzari, I.G.; Strigari, L.; Tomao, S.; Cortesi, E.; Rughetti, A.; et al. Immune effects of CDK4/6 inhibitors in patients with HR+/HER− metastatic breast cancer: Relief from immunosuppression is associated with clinical response. eBioMedicine 2022, 79, 104010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egelston, C.; Guo, W.; Yost, S.; Lee, J.S.; Rose, D.; Avalos, C.; Ye, J.; Frankel, P.; Schmolze, D.; Waisman, J.; et al. Pre-existing effector T-cell levels and augmented myeloid cell composition denote response to CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib and pembrolizumab in hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e002084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, S.J.; Schoening, C.; Eck, J.; Middendorf, C.; Lutsch, J.; Knoch, P.; von Ofen, A.J.; Gassmann, H.; Thiede, M.; Hauer, J.; et al. The Oncolytic Adenovirus XVir-N-31 Joins Forces with CDK4/6 Inhibition Augmenting Innate and Adaptive Antitumor Immunity in Ewing Sarcoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 1996–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeyer, J.L.; Lingo, J.J.; Kaemmer, C.A.; Scherer, A.; Warrier, A.; Voigt, E.; Raygoza Garay, J.A.; McGivney, G.R.; Brockman, Q.R.; Tang, A.; et al. CDK4/6-MEK Inhibition in MPNSTs Causes Plasma Cell Infiltration, Sensitization to PD-L1 Blockade, and Tumor Regression. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 3484–3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, L.R.; Garrido-Castro, A.C.; Lenehan, P.J.; Bollenrucher, N.; Stump, C.T.; Dougan, M.; Goel, S.; Shapiro, G.I.; Tolaney, S.M.; Dougan, S.K. PD-1 blockade and CDK4/6 inhibition augment nonoverlapping features of T cell activation in cancer. J. Exp. Med. 2023, 220, e20220729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckler, M.; Ali, L.R.; Clancy-Thompson, E.; Qiang, L.; Ventre, K.S.; Lenehan, P.; Roehle, K.; Luoma, A.; Boelaars, K.; Peters, V.; et al. Inhibition of CDK4/6 Promotes CD8 T-cell Memory Formation. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 2564–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelliott, E.J.; Kong, I.Y.; Zethoven, M.; Ramsbottom, K.M.; Martelotto, L.G.; Meyran, D.; Zhu, J.J.; Costacurta, M.; Kirby, L.; Sandow, J.J.; et al. CDK4/6 Inhibition Promotes Antitumor Immunity through the Induction of T-cell Memory. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 2582–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gocher, A.M.; Workman, C.J.; Vignali, D.A.A. Interferon-γ: Teammate or opponent in the tumour microenvironment? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 22, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawrzyniak, P.; Hartman, M.L. Dual role of interferon-gamma in the response of melanoma patients to immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, C.; Fu, X.; Cataldo, M.L.; Nardone, A.; Pereira, R.; Veeraraghavan, J.; Nanda, S.; Qin, L.; Sethunath, V.; Wang, T.; et al. Activation of the IFN Signaling Pathway is Associated with Resistance to CDK4/6 Inhibitors and Immune Checkpoint Activation in ER-Positive Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 4870–4882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Si, Y.; Xu, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Bi, C.; Sun, M.; Sun, H. Downregulation of the splicing regulator NSRP1 confers resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors via activation of interferon signaling in breast cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 108070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, K.; Lee, E.; Park, N.; Hur, J.; Cho, Y.B.; Katuwal, N.B.; Kim, S.K.; Lee, S.A.; Kim, I.; An, H.J.; et al. Deregulated Immune Pathway Associated with Palbociclib Resistance in Preclinical Breast Cancer Models: Integrative Genomics and Transcriptomics. Genes 2021, 12, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milanovic, M.; Fan, D.N.Y.; Belenki, D.; Däbritz, J.H.M.; Zhao, Z.; Yu, Y.; Dörr, J.R.; Dimitrova, L.; Lenze, D.; Monteiro Barbosa, I.A.; et al. Senescence-associated reprogramming promotes cancer stemness. Nature 2018, 553, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gleason, C.E.; Dickson, M.A.; Klein Dooley, M.E.; Antonescu, C.R.; Gularte-Mérida, R.; Benitez, M.; Delgado, J.I.; Kataru, R.P.; Tan, M.W.Y.; Bradic, M.; et al. Therapy-Induced Senescence Contributes to the Efficacy of Abemaciclib in Patients with Dedifferentiated Liposarcoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, X.; Pang, D. Pirfenidone inhibits CCL2-mediated Treg chemotaxis induced by palbociclib and fulvestrant in HR+/HER− breast cancer. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 142, 113059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruscetti, M.; Morris, J.P.; Mezzadra, R.; Russell, J.; Leibold, J.; Romesser, P.B.; Simon, J.; Kulick, A.; Ho, Y.-J.; Fennell, M.; et al. Senescence-Induced Vascular Remodeling Creates Therapeutic Vulnerabilities in Pancreas Cancer. Cell 2020, 181, 424–441.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knudsen, E.S.; Kumarasamy, V.; Chung, S.; Ruiz, A.; Vail, P.; Tzetzo, S.; Wu, J.; Nambiar, R.; Sivinski, J.; Chauhan, S.S.; et al. Targeting dual signalling pathways in concert with immune checkpoints for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Gut 2021, 70, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; LaPak, K.M.; Hennessey, R.C.; Yu, C.Y.; Shakya, R.; Zhang, J.; Burd, C.E. Stromal Senescence By Prolonged CDK4/6 Inhibition Potentiates Tumor Growth. Mol. Cancer Res. 2017, 15, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Yan, J.; Guo, Q.; Chi, Z.; Tang, B.; Zheng, B.; Yu, J.; Yin, T.; Cheng, Z.; Wu, X.; et al. Genetic Aberrations in the CDK4 Pathway Are Associated with Innate Resistance to PD-1 Blockade in Chinese Patients with Non-Cutaneous Melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 6511–6523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Liu, W.; Shen, Q.; Tao, R.; Li, C.; Shen, Q.; Lin, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yang, L.; Xie, G.; et al. Combination of PARP inhibitor and CDK4/6 inhibitor modulates cGAS/STING-dependent therapy-induced senescence and provides “one-two punch” opportunity with anti-PD-L1 therapy in colorectal cancer. Cancer Sci. 2023, 114, 4184–4201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Lee, J.D.; Paulson, K.; Voillet, V.; Berndt, A.; Church, C.; Lachance, K.; Park, S.Y.; Yamamoto, N.K.; Cromwell, E.A.; et al. Enhancing immunogenic responses through CDK4/6 and HIF2α inhibition in Merkel cell carcinoma. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Bu, X.; Wang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Geng, Y.; Nihira, N.T.; Tan, Y.; Ci, Y.; Wu, F.; Dai, X.; et al. Cyclin D–CDK4 kinase destabilizes PD-L1 via cullin 3–SPOP to control cancer immune surveillance. Nature 2018, 553, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, X.; Ding, D.; Yan, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, B.; Ma, L.; Ye, Z.; Ma, T.; Wu, Q.; Rodrigues, D.N.; et al. Phosphorylated RB Promotes Cancer Immunity by Inhibiting NF-κB Activation and PD-L1 Expression. Mol. Cell 2019, 73, 22–35.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Asfaha, S.; Dick, F.A. CDK4 Inhibitors Thwart Immunity by Inhibiting Phospho-RB-NF-κB Complexes. Mol. Cell 2019, 73, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majewska, J.; Agrawal, A.; Mayo, A.; Roitman, L.; Chatterjee, R.; Sekeresova Kralova, J.; Landsberger, T.; Katzenelenbogen, Y.; Meir-Salame, T.; Hagai, E.; et al. p16-dependent increase of PD-L1 stability regulates immunosurveillance of senescent cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2024, 26, 1336–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, T.; Fernandez-Martinez, A.; Agrawal, Y.; Pfefferle, A.D.; Chic, N.; Brasó-Maristany, F.; Gonzàlez-Farré, B.; Paré, L.; Villacampa, G.; Saura, C.; et al. Cell-cycle inhibition and immune microenvironment in breast cancer treated with ribociclib and letrozole or chemotherapy. NPJ Breast Cancer 2024, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, J.I.; Cosgrove, P.A.; Medina, E.F.; Nath, A.; Chen, J.; Adler, F.R.; Chang, J.T.; Khan, Q.J.; Bild, A.H. Cellular interactions within the immune microenvironment underpins resistance to cell cycle inhibition in breast cancers. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Ramani, V.; Bharti, V.; de Lima Bellan, D.; Saleh, N.; Uzhachenko, R.; Shen, C.; Arteaga, C.; Richmond, A.; Reddy, S.M.; et al. Dendritic cell therapy augments antitumor immunity triggered by CDK4/6 inhibition and immune checkpoint blockade by unleashing systemic CD4 T-cell responses. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e006019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelliott, E.J.; Mangiola, S.; Ramsbottom, K.M.; Zethoven, M.; Lim, L.; Lau, P.K.H.; Oliver, A.J.; Martelotto, L.G.; Kirby, L.; Martin, C.; et al. Combined BRAF, MEK, and CDK4/6 Inhibition Depletes Intratumoral Immune-Potentiating Myeloid Populations in Melanoma. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2021, 9, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Guldner, I.H.; Golomb, S.M.; Sun, L.; Harris, J.A.; Lu, X.; Zhang, S. Single-cell profiling guided combinatorial immunotherapy for fast-evolving CDK4/6 inhibitor-resistant HER2-positive breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, B.; Callejo, A.; Bar, J.; Berchem, G.; Bazhenova, L.; Saintigny, P.; Wunder, F.; Raynaud, J.; Girard, N.; Lee, J.J.; et al. A WIN Consortium phase I study exploring avelumab, palbociclib, and axitinib in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Med. 2022, 11, 2790–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel, D.; Kuchava, V.; Bondarenko, I.; Ivashchuk, O.; Reddy, S.; Jaal, J.; Kudaba, I.; Hart, L.; Matitashvili, A.; Pritchett, Y.; et al. Trilaciclib prior to chemotherapy and atezolizumab in patients with newly diagnosed extensive-stage small cell lung cancer: A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase II trial. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 148, 2557–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, M.J.; Sacco, A.G.; Qi, Y.; Bykowski, J.; Pittman, E.; Chen, R.; Messer, K.; Cohen, E.E.W.; Gold, K.A. A phase I study of avelumab, palbociclib, and cetuximab in patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2022, 135, 106219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Lee, J.S.; Yost, S.E.; Frankel, P.H.; Ruel, C.; Egelston, C.A.; Guo, W.; Padam, S.; Tang, A.; Martinez, N.; et al. Phase I/II trial of palbociclib, pembrolizumab and letrozole in patients with hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 154, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.S.; Martin, M.; Rugo, H.S.; Jones, S.; Im, S.-A.; Gelmon, K.; Harbeck, N.; Lipatov, O.N.; Walshe, J.M.; Moulder, S.; et al. Palbociclib and Letrozole in Advanced Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1925–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, E.L.; Ren, Y.; Wagle, N.; Mahtani, R.; Ma, C.; DeMichele, A.; Cristofanilli, M.; Meisel, J.; Miller, K.D.; Abdou, Y.; et al. PACE: A Randomized Phase II Study of Fulvestrant, Palbociclib, and Avelumab After Progression on Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 4/6 Inhibitor and Aromatase Inhibitor for Hormone Receptor–Positive/Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor–Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 2050–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pujol, J.-L.; Vansteenkiste, J.; Paz-Ares Rodríguez, L.; Gregorc, V.; Mazieres, J.; Awad, M.; Jänne, P.A.; Chisamore, M.; Hossain, A.M.; Chen, Y.; et al. Abemaciclib in Combination With Pembrolizumab for Stage IV KRAS-Mutant or Squamous NSCLC: A Phase 1b Study. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2021, 2, 100234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patnaik, A.; Yap, T.A.; Chung, H.C.; de Miguel, M.J.; Bang, Y.-J.; Lin, C.-C.; Su, W.-C.; Italiano, A.; Chow, K.H.; Szpurka, A.M.; et al. Safety and Clinical Activity of a New Anti-PD-L1 Antibody as Monotherapy or Combined with Targeted Therapy in Advanced Solid Tumors: The PACT Phase Ia/Ib Trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 1267–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugo, H.S.; Kabos, P.; Beck, J.T.; Jerusalem, G.; Wildiers, H.; Sevillano, E.; Paz-Ares, L.; Chisamore, M.J.; Chapman, S.C.; Hossain, A.M.; et al. Abemaciclib in combination with pembrolizumab for HR+, HER− metastatic breast cancer: Phase 1b study. npj Breast Cancer 2022, 8, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, J.W.; Mazieres, J.; Barlesi, F.; Dragnev, K.H.; Koczywas, M.; Göskel, T.; Cortot, A.B.; Girard, N.; Wesseler, C.; Bischoff, H.; et al. A Randomized Phase III Study of Abemaciclib Versus Erlotinib in Patients with Stage IV Non-small Cell Lung Cancer With a Detectable KRAS Mutation Who Failed Prior Platinum-Based Therapy: JUNIPER. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 578756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, T.S.K.; Wu, Y.-L.; Kudaba, I.; Kowalski, D.M.; Cho, B.C.; Turna, H.Z.; Castro, G.; Srimuninnimit, V.; Laktionov, K.K.; Bondarenko, I.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for previously untreated, PD-L1-expressing, locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-042): A randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 1819–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickler, M.N.; Tolaney, S.M.; Rugo, H.S.; Cortés, J.; Diéras, V.; Patt, D.; Wildiers, H.; Hudis, C.A.; O’Shaughnessy, J.; Zamora, E.; et al. MONARCH 1, A Phase II Study of Abemaciclib, a CDK4 and CDK6 Inhibitor, as a Single Agent, in Patients with Refractory HR+/HER− Metastatic Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 5218–5224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alley, E.W.; Lopez, J.; Santoro, A.; Morosky, A.; Saraf, S.; Piperdi, B.; van Brummelen, E. Clinical safety and activity of pembrolizumab in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma (KEYNOTE-028): Preliminary results from a non-randomised, open-label, phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerusalem, G.; Prat, A.; Salgado, R.; Reinisch, M.; Saura, C.; Ruiz-Borrego, M.; Nikolinakos, P.; Ades, F.; Filian, J.; Huang, N.; et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab + palbociclib + anastrozole for oestrogen receptor-positive/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative primary breast cancer: Results from CheckMate 7A8. Breast 2023, 72, 103580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Castro, A.C.; Graham, N.; Ali, L.R.; Herold, C.; Desrosiers, J.; Do, K.; Parsons, H.; Li, T.; Goel, S.; DiLullo, M.; et al. Phase I study of ribociclib (CDK4/6 inhibitor) with spartalizumab (PD-1 inhibitor) with and without fulvestrant in metastatic hormone receptor-positive breast cancer or advanced ovarian cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e010430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.R.; Wright, G.S.; Thummala, A.R.; Danso, M.A.; Popovic, L.; Pluard, T.J.; Han, H.S.; Vojnović, Ž.; Vasev, N.; Ma, L.; et al. Trilaciclib Prior to Chemotherapy in Patients with Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Final Efficacy and Subgroup Analysis from a Randomized Phase II Study. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaikovsky, A.C.; Sage, J. Beyond the Cell Cycle: Enhancing the Immune Surveillance of Tumors Via CDK4/6 Inhibition. Mol. Cancer Res. 2018, 16, 1454–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, J.; Sakai, H.; Tsurutani, J.; Tanabe, Y.; Masuda, N.; Iwasa, T.; Takahashi, M.; Futamura, M.; Matsumoto, K.; Aogi, K.; et al. Efficacy, safety, and biomarker analysis of nivolumab in combination with abemaciclib plus endocrine therapy in patients with HR-positive HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer: A phase II study (WJOG11418B NEWFLAME trial). J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e007126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, C.; Trub, A.; Ahn, A.; Taylor, M.; Ambani, K.; Chan, K.T.; Lu, K.-H.; Mahendra, C.A.; Blyth, C.; Coulson, R.; et al. INX-315, a Selective CDK2 Inhibitor, Induces Cell Cycle Arrest and Senescence in Solid Tumors. Cancer Discov. 2024, 14, 446–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Cai, Q.; Pan, C.; Liu, W.; Li, L.; Liu, J.; Gao, M.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Rao, Y.; et al. CDK2 Inhibition Enhances Antitumor Immunity by Increasing IFN Response to Endogenous Retroviruses. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2022, 10, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Wang, W.; Gao, L.; Shao, X.; Wang, X. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors enhance programmed cell death protein 1 immune checkpoint blockade efficacy in triple-negative breast cancer by affecting the immune microenvironment. Cancer 2024, 130, 1449–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, A.; Chenoweth, A.M.; Quist, J.; Sow, H.S.; Malaktou, C.; Ferro, R.; Hoffmann, R.M.; Osborn, G.; Sachouli, E.; French, E.; et al. CDK Inhibition Primes for Anti-PD-L1 Treatment in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Models. Cancers 2022, 14, 3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Christensen, C.L.; Dries, R.; Oser, M.G.; Deng, J.; Diskin, B.; Li, F.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yin, Y.; et al. CDK7 Inhibition Potentiates Genome Instability Triggering Anti-tumor Immunity in Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 37–54.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, R.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Y.; Tang, J.; Hong, J.; Zhou, X.; Zong, Y.; Xu, Y.; et al. CDK7 inhibitor THZ1 enhances antiPD-1 therapy efficacy via the p38α/MYC/PD-L1 signaling in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, Q.; Zou, P.; Huang, X.; Wu, C.; Tan, L. CDK12/13 inhibition induces immunogenic cell death and enhances anti-PD-1 anticancer activity in breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 2020, 495, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquelot, N.; Yamazaki, T.; Roberti, M.P.; Duong, C.P.M.; Andrews, M.C.; Verlingue, L.; Ferrere, G.; Becharef, S.; Vétizou, M.; Daillère, R.; et al. Sustained Type I interferon signaling as a mechanism of resistance to PD-1 blockade. Cell Res. 2019, 29, 846–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Diaz, A.; Shin, D.S.; Moreno, B.H.; Saco, J.; Escuin-Ordinas, H.; Rodriguez, G.A.; Zaretsky, J.M.; Sun, L.; Hugo, W.; Wang, X.; et al. Interferon Receptor Signaling Pathways Regulating PD-L1 and PD-L2 Expression. Cell Rep. 2017, 19, 1189–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, E.; Wu, J.; Huang, J.; Zhu, W.; Sun, H.; Wang, X.; Lin, D.; Li, X.; Shi, D.; Liu, Z.; et al. FLI1 promotes IFN-γ-induced kynurenine production to impair anti-tumor immunity. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zak, J.; Pratumchai, I.; Marro, B.S.; Marquardt, K.L.; Zavareh, R.B.; Lairson, L.L.; Oldstone, M.B.A.; Varner, J.A.; Hegerova, L.; Cao, Q.; et al. JAK inhibition enhances checkpoint blockade immunotherapy in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma. Science 2024, 384, eade8520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, D.; Marmarelis, M.E.; Foley, C.; Bauml, J.M.; Ye, D.; Ghinnagow, R.; Ngiow, S.F.; Klapholz, M.; Jun, S.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Combined JAK inhibition and PD-1 immunotherapy for non–small cell lung cancer patients. Science 2024, 384, eadf1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Xie, M.; Zhang, R.; Zhong, J.; Chen, Z.; Lin, J.; Zou, Y.; Wu, Y.; Kang, T.; Zhou, L. TMEM199 promotes PD-L1 expression and tumor immune evasion by activating the recycling of IFNGR1/2. Cancer Lett. 2025, 639, 218187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charles, A.; Bourne, C.M.; Korontsvit, T.; Aretz, Z.E.H.; Mun, S.S.; Dao, T.; Klatt, M.G.; Scheinberg, D.A. Low-dose CDK4/6 inhibitors induce presentation of pathway specific MHC ligands as potential targets for cancer immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology 2021, 10, 1916243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Cui, L.; Zhao, X.; Bai, H.; Cai, S.; Wang, G.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, J.; Chen, S.; Song, J.; et al. Use of Immunotherapy With Programmed Cell Death 1 vs Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1 Inhibitors in Patients With Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Xin, L.; Liang, C.; Li, L.; Song, Q.; Long, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, D.; Shi, W.; Zhang, J.; et al. Efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1 inhibitor versus anti-PD-L1 inhibitor in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small cell lung cancer: A multicenter retrospective study. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Bai, H.; Wang, C.; Seery, S.; Wang, Z.; Duan, J.; Li, S.; Xue, P.; Wang, G.; Sun, Y.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of First-Line Immunotherapy Combinations for Advanced NSCLC: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021, 16, 1099–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Wu, P.; Li, D.; Zhou, J.; Lin, C.; Gu, X.; Shang, D.; Ma, R.; Liu, J.; Zhang, G.; et al. Efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1 versus anti-PD-L1 in perioperative immunotherapy: A comprehensive reanalysis of randomized controlled trials. Med 2025, 6, 100669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, E.; Miyoshi, Y.; Dozono, K.; Kawaguchi, T.; Toi, M. Association of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Absolute Lymphocyte Count With Clinical Outcomes in Advanced Breast Cancer in the MONARCH 2 Trial. Oncologist 2024, 29, e319–e329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peuker, C.A.; Yaghobramzi, S.; Grunert, C.; Keilholz, L.; Gjerga, E.; Hennig, S.; Schaper, S.; Na, I.-K.; Keller, U.; Brucker, S.; et al. Treatment with ribociclib shows favourable immunomodulatory effects in patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer—findings from the RIBECCA trial. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 162, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

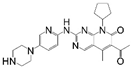

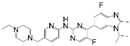

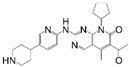

| Names | Structure | Targets and IC50 | Half-Life, h | Approved Year | Conditions | Dosage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palbociclib |  | CDK4: 11 nM CDK6: 16 nM | 29–33 | 2015 |

| 125 mg po once daily for 21 days, 28 day a cycle |

| Abemaciclib |  | CDK4: 2 nM CDK6: 10 nM | 18.3 | 2016 |

| 150 mg po bid |

| Ribociclib |  | CDK4: 10 nM CDK6: 39 nM | 32 | 2017 |

| 600 mg po once daily for 21 days, 28 day a cycle |

| Trilaciclib |  | CDK4: 1 nM CDK6: 4 nM | 14 | 2021 |

| 240 mg/m2, 30 min intravenous infusion, completed within 4 h prior to the chemotherapy |

| Dalpiciclib |  | CDK4: 12 nM CDK6: 10 nM | 34–37 | 2022 |

| 150 mg po once daily for 21 days, 28 day a cycle |

| NCT Number | Study Title | Study Status | Duration of Research | Phases | Conditions | Enrollment | Research Design and Arms | Important Safety Notice | Summary of Effectiveness | Immunomodulatory Effects | Study Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT02778685 | Pembrolizumab, endocrine therapy, and palbociclib in treating postmenopausal patients with newly diagnosed metastatic stage IV estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer | Active not recruiting | 2016/9/30- | Phase I/II | Metastatic HR+\HER2− breast cancer | 20 | Pembrolizumab + Letrozole + Palbociclib | G3–4 toxicities were neutropenia (83%), leucopenia (65%), lymphocytopenia (26%), elevated LFTs (17%) | The median PFS and OS were 25.2 m and 36.9 m, respectively | The proportion of type 1 dendritic cells in the circulating dendritic cells increases. | [110] |

| NCT03147287 | Palbociclib after CDK and endocrine therapy (PACE) | Active not recruiting | 2017/9/5- | Phase II | Metastatic HR+\HER2− breast cancer, which has progressed on previous CDK4/6i+ET (AI or tamoxifen) | 220 | Arm A: Fulvestrant (F) Arm B: Fulvestrant + Palbociclib (F + P) Arm C: Fulvestrant + Palbociclib + Avelumab (F + P + A) | The most common G3–4 TRAEs with F + P + A included neutropenia (49.1%), fatigue (5.7%). The most common G3–4 irAEs were increased AST (1.9%) and ALT (1.9%). No cases of pneumonitis or ILD were observed. | The median PFS were 4.8 m (Arm A), 4.6 m (Arm B) and 8.1 m (Arm C) | Not mentioned. | [112] |

| NCT03498378 | Avelumab, cetuximab, and palbociclib in recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | Active not recruiting | 2018/6/6- | Phase I | Recurrent/metastatic HNSCC | 24 | Avelumab + Cetuximab + Palbociclib (75/100/125 mg) | 9 patients (75%) experienced G3–4 TRAEs, most of which were hematological toxicities. | 3 patients (25%) experienced CR. The median PFS was 6.5 m and the median OS was not reached | Not mentioned. | [109] |

| NCT02791334 | A study of anti-PD-L1 checkpoint antibody (LY3300054) alone and in combination in participants with advanced refractory solid tumors (PACTs) | Completed | 2016/6/29–2024/6/27 | Phase I | Advanced refractory solid tumors (The study protocol enrolled patients without liver metastases and with normal liver enzyme levels) | 81 | Arm A: LY3300054 (70/200/700 mg, Q2W) Arm C: LY3300054 (70/200/700 mg, Q2W) + Abemaciclib | 7 patients (35%) in Arm C had G ≥ 3 TRAEs: diarrhea, fatigue, anemia, maculopapular rash, neutropenia. | DCRs of Arm C were 75.0% in the 70 mg, 50.0% in the 200 mg and 37.5% in the 700 mg | Increased frequencies in proliferating and activated T cells were not observed in the abemaciclib combination arm. | [114] |

| NCT02779751 | A study of abemaciclib (LY2835219) in participants with non-small-cell lung cancer or breast cancer | Active not Recruiting | 2016/11/14- | Phase Ib | Cohort A: Stage IV KRAS-mutant, PD-L1-positive (TPS ≥ 1%) NSCLC; Cohort B: Stage IV squamous NSCLC previously treated by one platinum chemotherapy | 25 | Abemaciclib + Pembrolizumab | Transaminase elevation (G ≥ 3 = 24%) and pneumonitis (G ≥ 3 = 12%) in cohort 1 were higher than which has previously been reported for either drug alone (One patient experienced a study treatment-related death of pneumonitis in cohort 1) | Cohort A: median PFS and OS were 7.6 m and 27.8 m, respectively, Cohort B: median PFS and OS were 3.3 m and 6.0 m, respectively | Not mentioned. | [113] |

| NCT02779751 | A study of abemaciclib (LY2835219) in participants with non-small-cell lung cancer or breast cancer | Active not Recruiting | 2016/11/14- | Phase Ib | Cohort 1: Metastatic HR+\HER2− breast cancer without systemic therapy in the metastasis Cohort 2: Metastatic HR+\HER2− breast cancer treated with ≥1 but ≤2 chemotherapy regimens in the metastasis | 54 | Arm A (Cohort 1): Abemaciclib + Pembrolizumab + Anastrozole Arm B (Cohort 2): Abemaciclib + Pembrolizumab | Cohort 1, 2 patients died due to TRAEs (both related to ILD). G ≥ 3 TEAEs were 69.2% (ALT increased (42.3%), AST increased (34.6%)). Cohort 2, G ≥ 3 TEAEs were 60.7% (neutropenia (28.6%), AST increased (17.9%)). | Cohort 1: Not reach; Cohort 2: The median PFS and OS were 8.9 m and 26.3 m, respectively | Not mentioned. | [115] |

| NCT04075604 | A study of neoadjuvant nivolumab + palbociclib + anastrozole in post-menopausal women and men with primary breast cancer (CheckMate 7A8) | Completed | 2019/10/18–2021/7/27 | Phase Ib/II | Primary ER+/HER2− breast cancer | 23 | Arm A: Abemaciclib + Nivolumab + Anastrozole Arm B: Palbociclib (125 mg, 100 mg) + Nivolumab + Anastrozole | Arm A was closed after enrolling 2 patients due to suggested risk of ILD/pneumonia [115,124]. Arm B was halted with 6 of 21 patients discontinuing treatment due to hepatotoxicity. | pCR was 0 of 9 patients in the palbociclib 125 mg group and 1 of 12 (8.3%) patients in the palbociclib 100 mg group | Not mentioned. | [120] |

| NCT03294694 | Ribociclib + PDR001 in breast cancer and ovarian cancer | Terminated | 2017/11/8–2020/10/14 | Phase I | Metastatic HR+\HER2− breast cancer Metastatic Ovarian Cancer | 33 | Arm A: Ribociclib (400/600 mg) + Spartalizumab Arm B: Ribociclib (600 mg) + Spartalizumab + Fulvestrant | Due the high rate of G3–4 hepatotoxicity (7/15) observed in Arm B, the study was closed early after 33 patients enrolled | The addition of spartalizumab had no significant improvement in the efficacy | Ribociclib+ spartalizumab induced a significant increase in circulating CD3+ CD45RO+ T cells that expressed the activation markers CD38, HLA-DR, and CX3CR1. | [121] |

| NCT03041311 | Carboplatin, Etoposide, and Atezolizumab with or without Trilaciclib (G1T28), a CDK4/6 Inhibitor, in Extensive-Stage SCLC | Terminated | 2017/6/29–2020/10/29 | Phase II | ES-SCLC | 107 | Arm A: Trilaciclib prior to chemotherapy and Atezolizumab Arm B: Placebo + chemotherapy and Atezolizumab | One (1.9%) SAE (Grade 2 deep vein thrombosis) was considered related to trilaciclib. | No significant differences in ORR, median PFS and OS | Arm A had a higher ratio of CD8+ T cells, activated CD8+ T cells to Tregs, and more clonal expansion. | [108] |

| NCT02978716 | Trilaciclib (G1T28), a CDK 4/6 Inhibitor, in Combination with Gemcitabine and Carboplatin in Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (mTNBC) | Terminated | 2017/2/2–2020/2/28 | Phase II | TNBC | 102 | Arm A: GCb on days 1 and 8 Arm B: Trilaciclib prior to GCb on days 1 and 8 Arm C: Trilaciclib days 1 and 8, and trilaciclib prior to GCb on days 2 and 9 | Not mentioned | Median OS was 12.6 m for Arm A, not reached for Arm B (p = 0.0016), 17.8 m for Arm C (p = 0.0004) | Patients who responded to GCb plus trilaciclib had a higher fraction of newly expanded clones than patients who responded to GCb alone. | [122] |

| NCT Number | Study Title | Study Status | Conditions | Interventions | Phases | Enrollment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT05766410 | A Randomized Study Comparing the Immune Modulation Effect of Ribociclib, Palbociclib, and Abemaciclib in ER+/HER2− EBC | Recruiting | Breast Cancer | Palbociclib Ribociclib Abemaciclib Letrozole | Phase II | 60 |

| NCT06113809 | Palbociclib and Pembrolizumab in Sarcoma | Recruiting | Sarcoma | Palbociclib Pembrolizumab | Phase I | 8 |

| NCT05205200 | Immune Therapy in HR+/HER2− Metastatic Breast Cancer (ENIGMA)-BCTOP-L-M02 | Recruiting | Breast Cancer | SHR-1316 SHR6390 Nab paclitaxel SERD/AI | Phase II | 338 |

| NCT06109207 | Neoadjuvant Camrelizumab with Dalpiciclib for Resectable Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas | Recruiting | Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma | Camrelizumab Dalpiciclib Dalpiciclib | Phase I | 6 |

| NCT06654297 | Neoadjuvant Camrelizumab with Palbociclib for Resectable Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinomas | Recruiting | Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma | Camrelizumab Palbociclib | Phase I | 6 |

| NCT04360941 | PAveMenT: Palbociclib and Avelumab in Metastatic AR+ Triple-Negative Breast Cancer | Recruiting | Breast Cancer | Palbociclib Avelumab | Phase I | 45 |

| NCT02896335 | Palbociclib and Pembrolizumab in Central Nervous System Metastases | Recruiting | Metastatic Malignant Neoplasm to Brain| | Palbociclib Pembrolizumab | Phase II | 45 |

| NCT06364956 | Phase Ib/II Trail of Neoadjuvant of Tislelizumab Combined with Palbociclib in Patients with Platinum-refractory Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma | Recruiting | Bladder Cancer | Tislelizumab Palbociclib | Phase I/II | 36 |

| NCT04841148 | Avelumab or Hydroxychloroquine with or Without Palbociclib to Eliminate Dormant Breast Cancer | Recruiting | Breast Cancer | Hydroxychloroquine Avelumab Palbociclib | Phase II | 96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Si, Y.; Li, H.; Shi, Y. The Dual Effects of CDK4/6 Inhibitors on Tumor Immunity. Cancers 2025, 17, 3997. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243997

Si Y, Li H, Shi Y. The Dual Effects of CDK4/6 Inhibitors on Tumor Immunity. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):3997. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243997

Chicago/Turabian StyleSi, Yiran, Hongli Li, and Yehui Shi. 2025. "The Dual Effects of CDK4/6 Inhibitors on Tumor Immunity" Cancers 17, no. 24: 3997. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243997

APA StyleSi, Y., Li, H., & Shi, Y. (2025). The Dual Effects of CDK4/6 Inhibitors on Tumor Immunity. Cancers, 17(24), 3997. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243997