The Impact of Demographic and Clinico-Pathological Characteristics on Recurrence-Free Survival in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

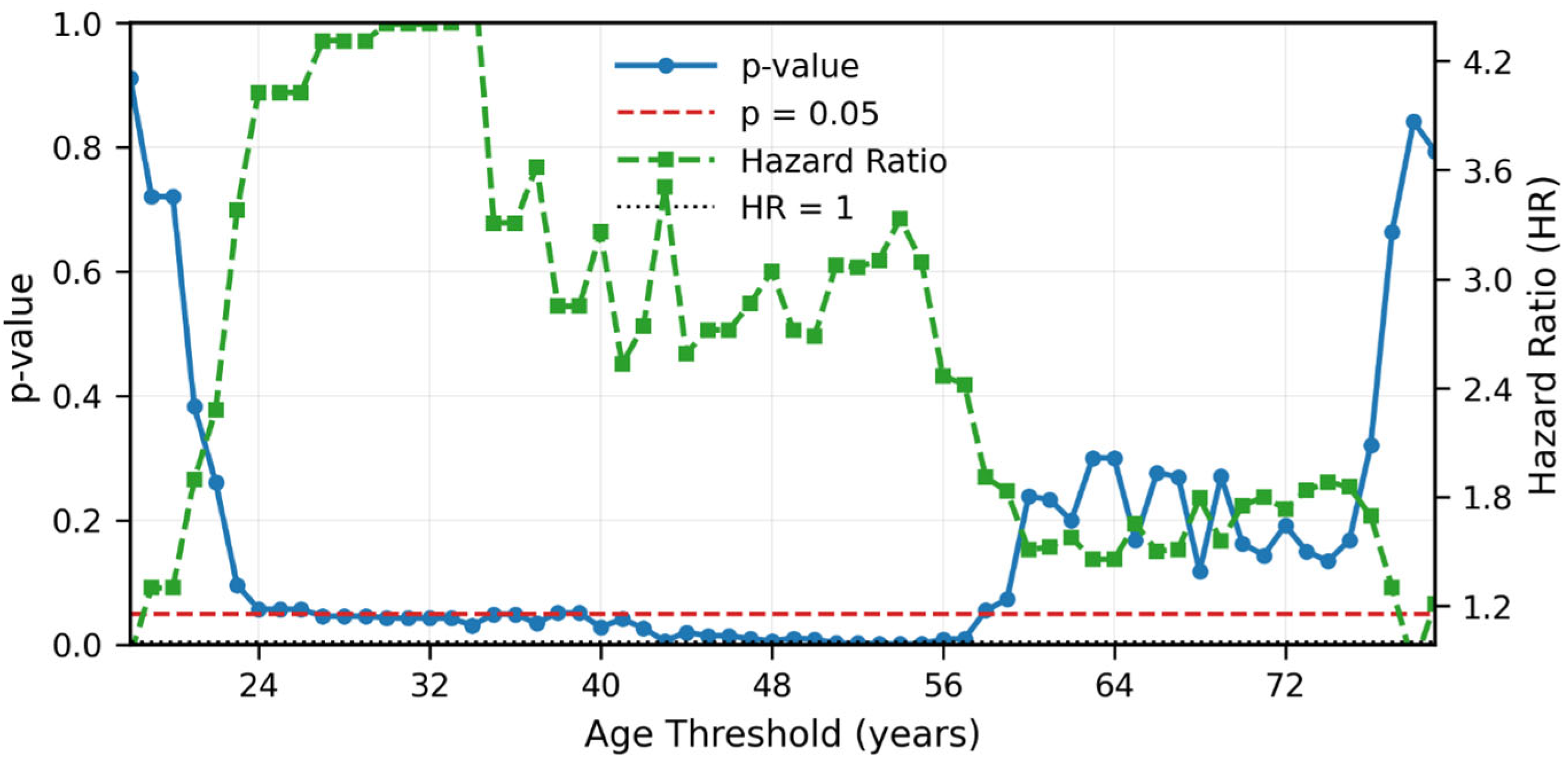

Statistical Methods

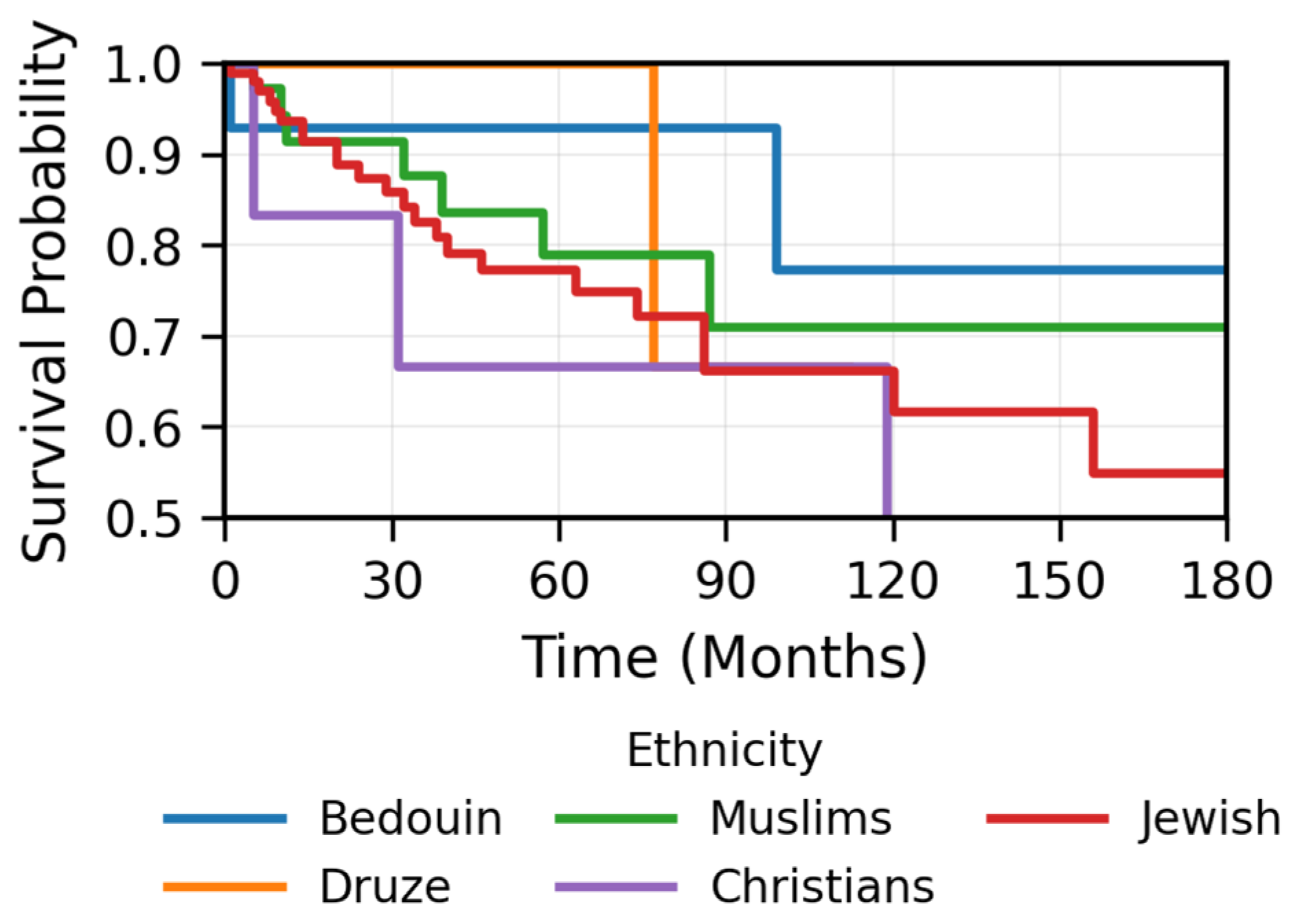

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Strength

- -

- One of the largest single-center studies focusing on NPC in a non-endemic region.

- -

- The median follow-up of 57 months allows for meaningful survival analysis and robust assessment of long-term recurrence patterns.

- -

- Our treatment protocols reflect real-world clinical practice.

- -

- All the patients were treated by single physician who is specialist in head and neck malignancies.

- -

- Most of the patients were treated with modern radiotherapy techniques.

4.2. Limitations

- -

- Nearly 20% of the patient pathology reports lacked histological subtyping, which is known to have prognostic relevance. However, based on the consistency observed in our non-endemic Mediterranean cohort and previous studies from our region, the distribution and trends appear comparable; therefore, we believe this minor limitation did not affect the validity of our results.

- -

- EBV status, which is known to have prognostic importance, was not recorded in 60% of the pathology reports; nevertheless, the strong association between the non-keratinizing subtype predominant in our cohort and EBV positivity reduces the impact of this limitation. Moreover, data on EBV DNA titers were also unavailable, this marker is not routinely tested in our clinical practice due to ongoing debate regarding its clinical relevance, cost-effectiveness, and limited adoption by many physicians awaiting ongoing trials (e.g., NRG group NCT02135042).

- -

- The findings regarding ethnic differences, particularly the higher prevalence among younger Bedouin patients and the non-significant favorable prognosis, are limited by the small sample size and potential confounding by age and require further investigation.

- -

- Limitations applicable to all retrospective studies.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.Q.; Wang, T.M.; Ji, M.; Mai, Z.M.; Tang, M.; Wang, R.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Xiao, R.; Yang, D.; et al. A Polygenic Risk Score for Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Shows Potential for Risk Stratification and Personalized Screening. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, W.H.; Luo, X.Y.; Feng, B.J.; Ruan, H.L.; Bei, J.X.; Liu, W.S.; Qin, H.D.; Feng, Q.S.; Chen, L.Z.; Yao, S.Y.; et al. Traditional Cantonese Diet and Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Risk: A Large-Scale Case-Control Study in Guangdong, China. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, A.O.; Gallagher, L.W.; Sharma, R.K.; Spielman, D.; Golub, J.S.; Overdevest, J.B.; Yan, C.H.; Deconde, A.; Gudis, D.A. Impact of Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status on Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Disease-Specific and Conditional Survival. J. Neurol. Surg. B Skull Base 2021, 83, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsao, S.W.; Yip, Y.L.; Tsang, C.M.; Pang, P.S.; Lau, V.M.Y.; Zhang, G.; Lo, K.W. Etiological Factors of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Oral. Oncol. 2014, 50, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, L.S.; Dawson, C.W. Epstein-Barr Virus and Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Chin. J. Cancer 2014, 33, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.F.; Li, Y.H.; Xie, S.H.; Ling, W.; Chen, S.H.; Liu, Q.; Huang, Q.H.; Cao, S.M. Incidence Trend of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma from 1987 to 2011 in Sihui County, Guangdong Province, South China: An Age-Period-Cohort Analysis. Chin. J. Cancer 2015, 34, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sarraf, M.; LeBlanc, M.; Giri, P.G.S.; Fu, K.K.; Cooper, J.; Vuong, T.; Forastiere, A.A.; Adams, G.; Sakr, W.A.; Schuller, D.E.; et al. Chemoradiotherapy versus Radiotherapy in Patients with Advanced Nasopharyngeal Cancer: Phase III Randomized Intergroup Study 0099. J. Clin. Oncol. 1998, 16, 1310–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Hu, G.-Q.; Zhang, N.; Zhu, X.-D.; Yang, K.-Y.; Jin, F.; Shi, M.; Chen, Y.-P.; Hu, W.-H.; et al. Gemcitabine and Cisplatin Induction Chemotherapy in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1124–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, W.F.; Chen, N.Y.; Zhang, N.; Hu, G.Q.; Xie, F.Y.; Sun, Y.; Chen, X.Z.; Li, J.G.; Zhu, X.D.; et al. Induction Chemotherapy plus Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy versus Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy Alone in Locoregionally Advanced Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: A Phase 3, Multicentre, Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 1509–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.I.; Sham, J.S.T. Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Lancet 2005, 365, 2041–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.P.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Q.; Yang, K.Y.; Jin, F.; Zhu, X.D.; Shi, M.; Hu, G.Q.; Hu, W.H.; Sun, Y.; et al. Metronomic Capecitabine as Adjuvant Therapy in Locoregionally Advanced Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: A Multicentre, Open-Label, Parallel-Group, Randomised, Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2021, 398, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, J.; Wang, L.; Tan, S.H.; Li, J.G.; Yi, J.; Ong, E.H.W.; Tan, L.L.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, X.; Chen, Q.; et al. Adjuvant Capecitabine Following Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy in Locoregionally Advanced Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 1776–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.-L.; Li, X.-Y.; Yang, J.-H.; Wen, D.-X.; Guo, S.-S.; Liu, L.-T.; Li, Y.-F.; Luo, M.-J.; Xie, S.-Y.; Liang, Y.-J.; et al. Neoadjuvant and Adjuvant Toripalimab for Locoregionally Advanced Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: A Randomised, Single-Centre, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 2 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2024, 25, 1563–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Zhang, B.; Su, Y.; Pan, Y.; Ye, Z.; Cai, R.; Qin, G.; Kong, X.; Mo, Y.; Zhang, R.; et al. Induction Chemotherapy Followed by Radiotherapy vs Chemoradiotherapy in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2024, 10, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.L.; Guo, R.; Zhang, N.; Deng, B.; Chen, L.; Cheng, Z.B.; Huang, J.; Hu, W.H.; Huang, S.H.; Luo, W.J.; et al. Effect of Radiotherapy Alone vs Radiotherapy with Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy on Survival without Disease Relapse in Patients with Low-Risk Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2022, 328, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.L.; Xu, F.; Song, D.; Huang, M.Y.; Huang, Y.S.; Deng, Q.L.; Li, Y.Y.; Shao, J.Y. Development of a Nomogram Model for Treatment of Nonmetastatic Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2029882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.L.; Guo, Q.; Ng, W.T.; Lin, S.; Ma, T.S.W.; Xu, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Li, J.; Lu, T.; Choi, H.C.W.; et al. Prognostic Factors for Overall Survival in Nasopharyngeal Cancer and Implication for TNM Staging by UICC: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 703995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ka-Yue Chow, L.; Lai-Shun Chung, D.; Tao, L.; Chan, K.F.; Tung, S.Y.; Cheong Ngan, R.K.; Ng, W.T.; Wing-Mui Lee, A.; Yau, C.C.; Lai-Wan Kwong, D.; et al. Epigenomic Landscape Study Reveals Molecular Subtypes and EBV-Associated Regulatory Epigenome Reprogramming in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. eBioMedicine 2022, 86, 104357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenoci, D.; Resteghini, C.; Serafini, M.S.; Pistore, F.; Canevari, S.; Ma, B.; Cavalieri, S.; Alfieri, S.; Trama, A.; Licitra, L.; et al. Tumor Molecular Landscape of Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) Related Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma in EBV-Endemic and Non-Endemic Areas: Implications for Improving Treatment Modalities. Transl. Res. 2024, 265, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiess, E.; Jensen, K.H.; Kristensen, M.H.; Johansen, J.; Eriksen, J.G.; Maare, C.; Andersen, M.; Farhadi, M.; Hansen, C.R.; Overgaard, J.; et al. Epidemiology and Treatment Outcome of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma in a Low-Incidence Population—A DAHANCA Analysis in Denmark 2000–2018. Acta Oncol. 2024, 63, 850–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsavaf, M.B.; Marquardt, M.; Abouammo, M.D.; Xu, M.; Elguindy, A.; Grecula, J.; Baliga, S.; Konieczkowski, D.; Gogineni, E.; Bhateja, P.; et al. Patient Characteristics and Treatment Outcomes of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma in Nonendemic Regions. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e251895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Sela, G.; Kuten, A.; Minkov, I.; Gov-Ari, E.; Ben-Izhak, O. Prevalence and Relevance of EBV Latency in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma in Israel. J. Clin. Pathol. 2004, 57, 290–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haimi, M.; Ben Arush, M.W.; Bar-Sela, G.; Gez, E.; Bernstein, Z.; Postovsky, S.; Ben Barak, A.; Kuten, A. Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma in the Pediatric Age Group: The Northern Israel (Rambam) Medical Center Experience, 1989–2004. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2005, 27, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Yang, H.; Ying, S.; Lu, H.; Wang, W.; Lv, J.; Xiong, H.; Hu, W. High HLA-F Expression Is a Poor Prognosis Factor in Patients with Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Anal. Cell Pathol. 2018, 2018, 7691704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Huang, T.; Ni, C.; Yang, P.; Chen, S. Diagnostic Capacity of RASSF1A Promoter Methylation as a Biomarker in Tissue, Brushing, and Blood Samples of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. eBioMedicine 2017, 18, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Meng, Z.; Yang, D.; Wu, T.; Qin, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Cao, C.; Kang, M. Prognostic Analysis of Early-Onset and Late-Onset Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: A Retrospective Study. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.D.; Chen, F.; He, Y.X.; Chen, X.D.; Zhang, G.Y.; Li, Z.K.; Hong, J.; Xie, D.; Cai, M.Y. Old Age at Diagnosis Increases Risk of Tumor Progression in Nasopharyngeal Cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 66170–66181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.G.; Zhu, X.D.; Tan, A.H.; Jiang, Y.M.; Qu, S.; Su, F.; Xu, G.Z. Induction Chemotherapy Followed by Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy versus Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy with or without Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Locoregionally Advanced Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: Meta-Analysis of 1096 Patients from 11 Randomized Controlled Trials. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2013, 14, 515–521. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Y.L.; Wang, C.T.; Yang, X.L.; He, S.S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y. The Impairment of Induction Chemotherapy for Stage II Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Treated with Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy with or without Concurrent Chemotherapy: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 2970–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.; Lim, W.T.; Fong, K.W.; Cheah, S.L.; Soong, Y.L.; Ang, M.K.; Ng, Q.S.; Tan, D.; Ong, W.S.; Tan, S.H.; et al. Concurrent Chemo-Radiation with or without Induction Gemcitabine, Carboplatin, and Paclitaxel: A Randomized, Phase 2/3 Trial in Locally Advanced Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2015, 91, 952–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fountzilas, G.; Ciuleanu, E.; Bobos, M.; Kalogera-fountzila, A.; Eleftheraki, A.G.; Karayannopoulou, G.; Zaramboukas, T.; Nikolaou, A.; Markou, K.; Resiga, L.; et al. Induction Chemotherapy Followed by Concomitant Radiotherapy and Weekly Cisplatin versus the Same Concomitant Chemoradiotherapy in Patients with Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: A Randomized Phase II Study Conducted by the Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group (HeCOG) with Biomarker Evaluation. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabani, P.; Barnes, J.; Lin, A.J.; Rudra, S.; Oppelt, P.; Adkins, D.; Rich, J.T.; Zevallos, J.P.; Daly, M.D.; Gay, H.A.; et al. Induction Chemotherapy in the Treatment of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: Clinical Outcomes and Patterns of Care. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 3592–3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, M.S.; Tin, A.; Mian, A.; Ali, A.; O’Hara, J.; Kovarik, J.; Patil, R.; Aynsley, E.; Kelly, C. Survival Outcomes for Patients with Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma in Non–Endemic Region in the UK Treated with Intensity Modulated Based Radiotherapy 65 Gy in 30 Fractions ± Weekly Cisplatin Chemotherapy. Rep. Pract. Oncol. Radiother. 2022, 27, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Galindo, C.; Krailo, M.D.; Krasin, M.J.; Huang, L.; Beth McCarville, M.; Hicks, J.; Pashankar, F.; Pappo, A.S. Treatment of Childhood Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma with Induction Chemotherapy and Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy: Results of the Children’s Oncology Group ARAR0331 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 3369–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.F.; Pan, G.S.; Du, C.R.; Ni, M.S.; Zhai, R.P.; He, X.Y.; Shen, C.Y.; Lu, X.G.; Hu, C.S.; Ying, H.M. Prognostic Value of Circulating Epstein-Barr Virus DNA Level Post-Induction Chemotherapy for Patients with Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: A Recursive Partitioning Risk Stratification Analysis. Radiother. Oncol. 2023, 185, 109721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xie, H.; Li, Y.; Theodoropoulos, N.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, C.; Wen, C.; Rozek, L.S.; Boffetta, P. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Nasopharyngeal Cancer with an Emphasis among Asian Americans. Int. J. Cancer 2022, 151, 1291–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepan, K.O.; Mazul, A.L.; Skillington, S.A.; Paniello, R.C.; Rich, J.T.; Zevallos, J.P.; Jackson, R.S.; Pipkorn, P.; Massa, S.; Puram, S.V. The Prognostic Significance of Race in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Varies by Histological Subtype. Head Neck 2021, 43, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M.; Kuten, A.; Arbel, M.; Ben-Schachar, M.; Epelbaum, R.; Wajsbort, R.; Klein, B.; Cohen, Y.; Robinson, E. Carcinoma of the Nasopharynx in Northern Israel: Epidemiology and Treatment Results. J. Surg. Oncol. 1988, 37, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgman, J.; Modan, B.; Shilon, M.; Rappaport, Y.; Shanon, E. Nasopharyngeal Cancer in a Total Population: Selected Clinical and Epidemiological Aspects. Br. J. Cancer 1977, 36, 783–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rottenberg, Y.; Levine, H.; Keinan-Boker, L.; Derazne, E.; Leiba, A.; Kark, J.D. Risk of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Penetrates across Immigrant Generations: A Migrant Cohort Study of 2.3 Million Jewish Israeli Adolescents. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 140, 1060–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Value (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Bedouin | 15 (8.5) |

| Druze | 8 (4.5) | |

| Muslims | 42 (23.5) | |

| Christian | 8 (4.5) | |

| Jewish | 106 (59) | |

| Gender | F | 33(18) |

| M | 148 (82) | |

| Age | >25 | 88 (159) |

| <25 | 22 (12) | |

| >65 | 140 (22.5) | |

| <65 | 41 (77.5) | |

| >75 | 26 (14.5) | |

| <75 | 155 (85.5) | |

| Smoking | 1 | 76 (41.5) |

| 2 | 75 (42) | |

| Unknown | 30 (16.5) | |

| ECOG PS | 0 | 125 (69) |

| 1 | 44 (24.5) | |

| 2 | 5 (2.5) | |

| 3 | 1 (0.5) | |

| Unknown | 6 (3.5) | |

| MRI | Yes | 126 (69.5) |

| No | 32 (17.5) | |

| Unknown | 23 (12.5) | |

| PET-CT | Yes | 152 (84) |

| No | 19 (10.5) | |

| Unknown | 10 (5.5) | |

| T | 0 | 1 (0.5) |

| 1 | 55 (30.5) | |

| 2 | 44 (24.5) | |

| 3 | 54 (30) | |

| 4 | 26 (14.5) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0.5) | |

| N | 0 | 32 (17.5) |

| 1 | 50 (27.5) | |

| 2 | 85 (47) | |

| 3 | 13 (7) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0.5) | |

| Stage | 1 | 8 (4.5) |

| 2 | 38 (21) | |

| 3 | 94 (52) | |

| 4a | 40 (22) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0.5) | |

| Induction chemotherapy | No | 53(29) |

| Yes | 128 (71) | |

| Induction type | Cisplatin-5-Fluorouracil | 34 (54) |

| Cisplatin-Gemzar | 68 (26.5) | |

| Other | 26 (19.5) | |

| Induction cycles | 1 | 47 (37) |

| 2 | 61 (47.5) | |

| 3 | 8 (6) | |

| 4 | 2 (1.5) | |

| Unknown | 10 (8) | |

| Radiotherapy technique | 2D + 3D | 21 (11.5) |

| VMAT | 160 (88.5) | |

| Concurrent chemotherapy | Carboplatin | 24 (13.5) |

| Cisplatin | 131 (72.5) | |

| None | 26 (14.5) | |

| Histological subtypes | Non-keratinizing | 140 (77.5) |

| Keratinizing | 2 (1) | |

| Unknown | 39 (21.5) | |

| EBV status | Positive | 53 (29.5) |

| Negative | 20 (11) | |

| Unknown | 108 (59.5) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Awawda, M.; Hanna, M.; Awawdi, A.; Salman, S.; Shirron, N.; Billan, S. The Impact of Demographic and Clinico-Pathological Characteristics on Recurrence-Free Survival in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Cancers 2025, 17, 3996. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243996

Awawda M, Hanna M, Awawdi A, Salman S, Shirron N, Billan S. The Impact of Demographic and Clinico-Pathological Characteristics on Recurrence-Free Survival in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):3996. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243996

Chicago/Turabian StyleAwawda, Muhammad, Majd Hanna, Ahmad Awawdi, Saeed Salman, Natali Shirron, and Salem Billan. 2025. "The Impact of Demographic and Clinico-Pathological Characteristics on Recurrence-Free Survival in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma" Cancers 17, no. 24: 3996. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243996

APA StyleAwawda, M., Hanna, M., Awawdi, A., Salman, S., Shirron, N., & Billan, S. (2025). The Impact of Demographic and Clinico-Pathological Characteristics on Recurrence-Free Survival in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Cancers, 17(24), 3996. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243996