Epithelioid Mesothelioma Cells Exhibit Increased Ferroptosis Sensitivity Compared to Non-Epithelioid Mesothelioma Cells

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and Reagents

2.2. Cell Survival and Death Assays

2.3. Preparation of Microbial Extracts

2.4. Screening of Ethanol Extract of Microbial Source

2.5. Identification of Brefeldin A from Fungal Strain BF-0398

2.6. Microarray Analysis

2.7. qRT-PCR

2.8. Detection of Lipid Peroxide

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

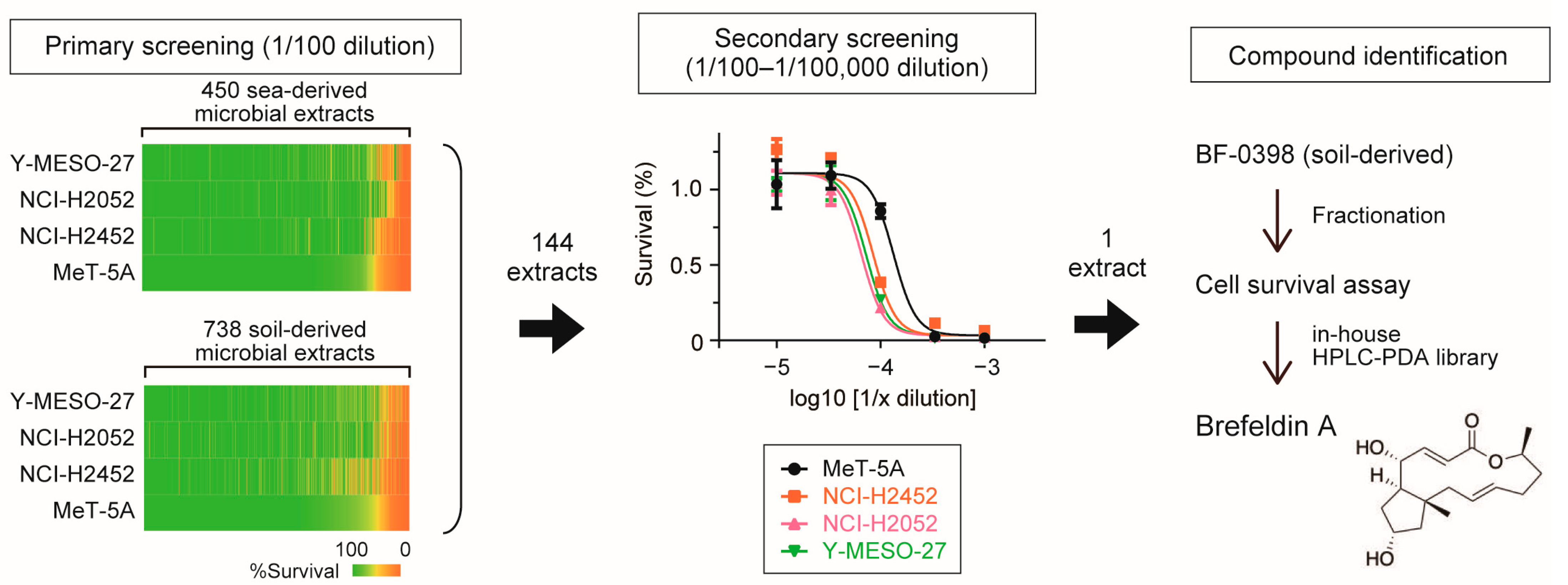

3.1. Identification of Brefeldin A as an Inhibitor of Mesothelioma Cell Proliferation

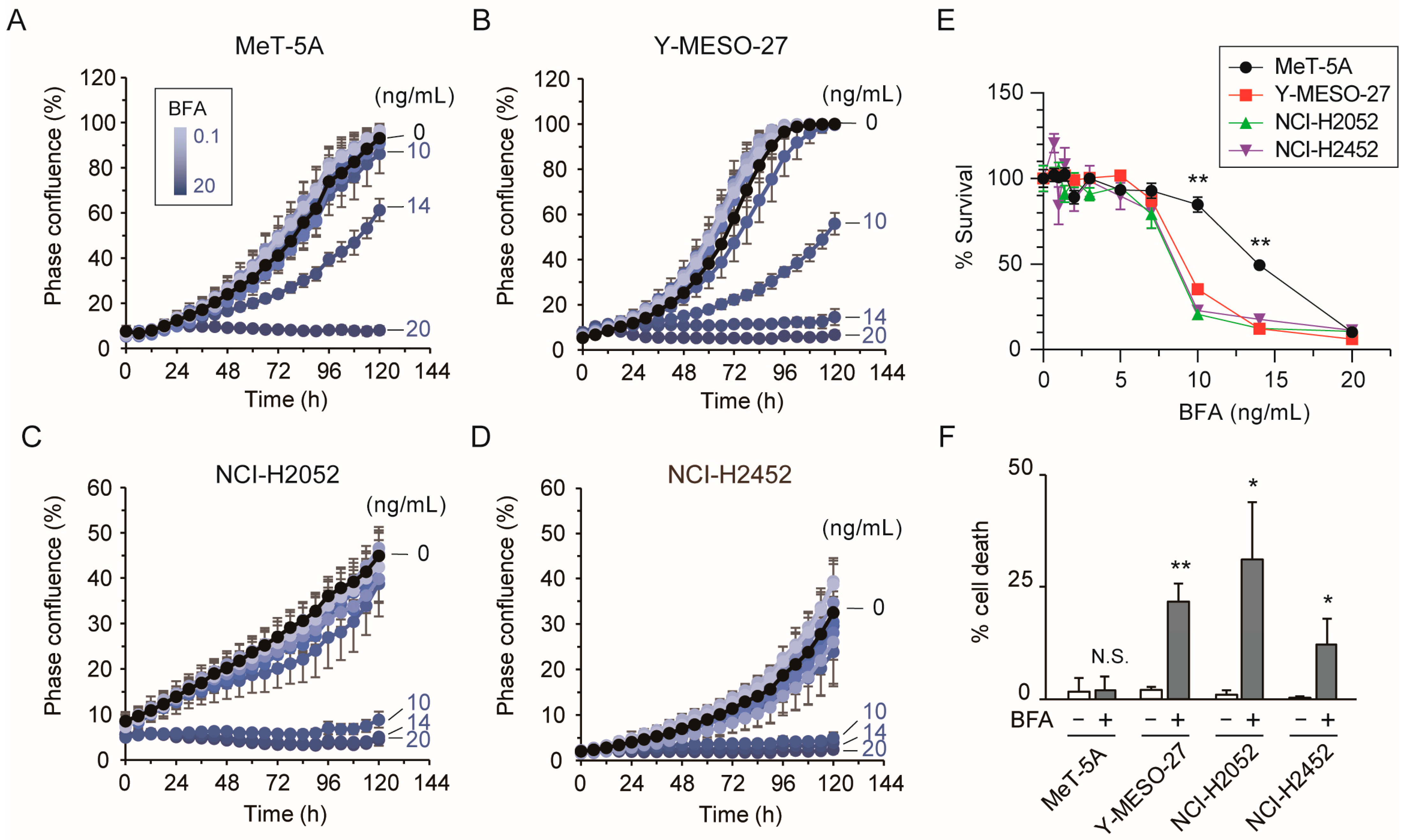

3.2. Low-Dose Brefeldin A Induces Cell Death in Mesothelioma Cells

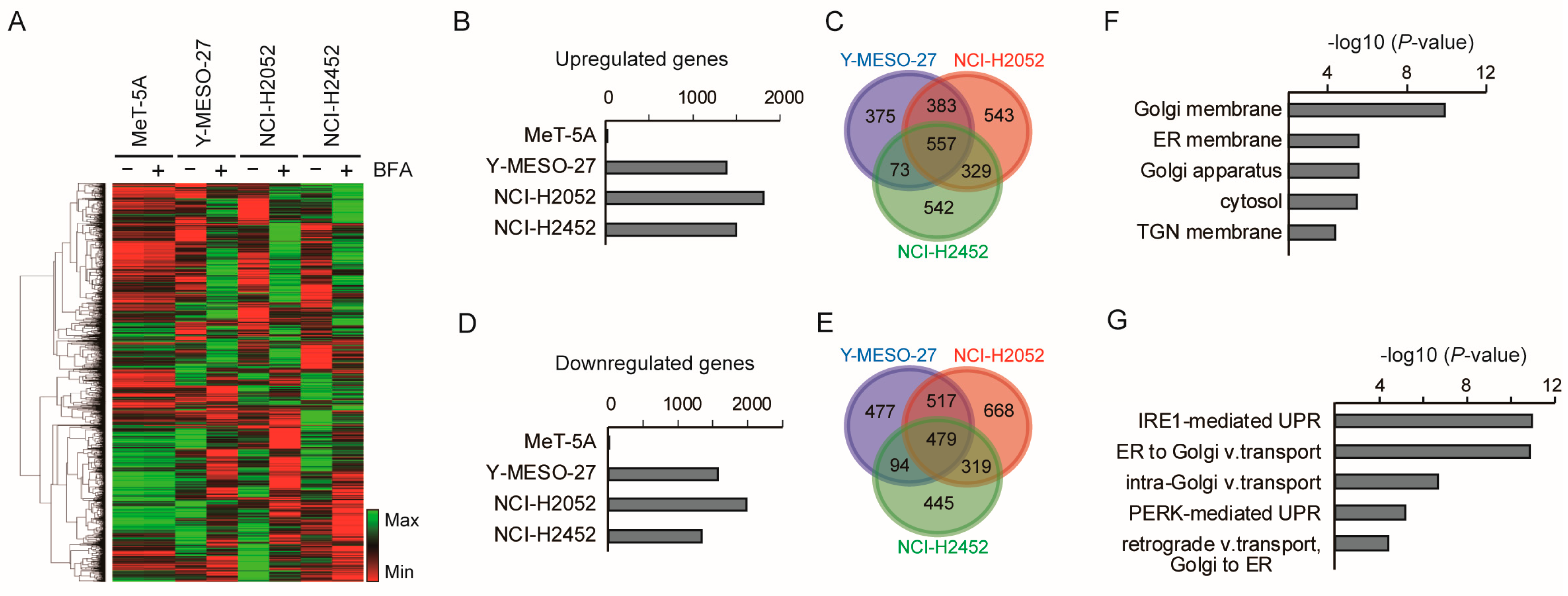

3.3. Low-Dose Brefeldin A Selectively Triggers Stress-Related Transcriptional Responses in Mesothelioma Cells

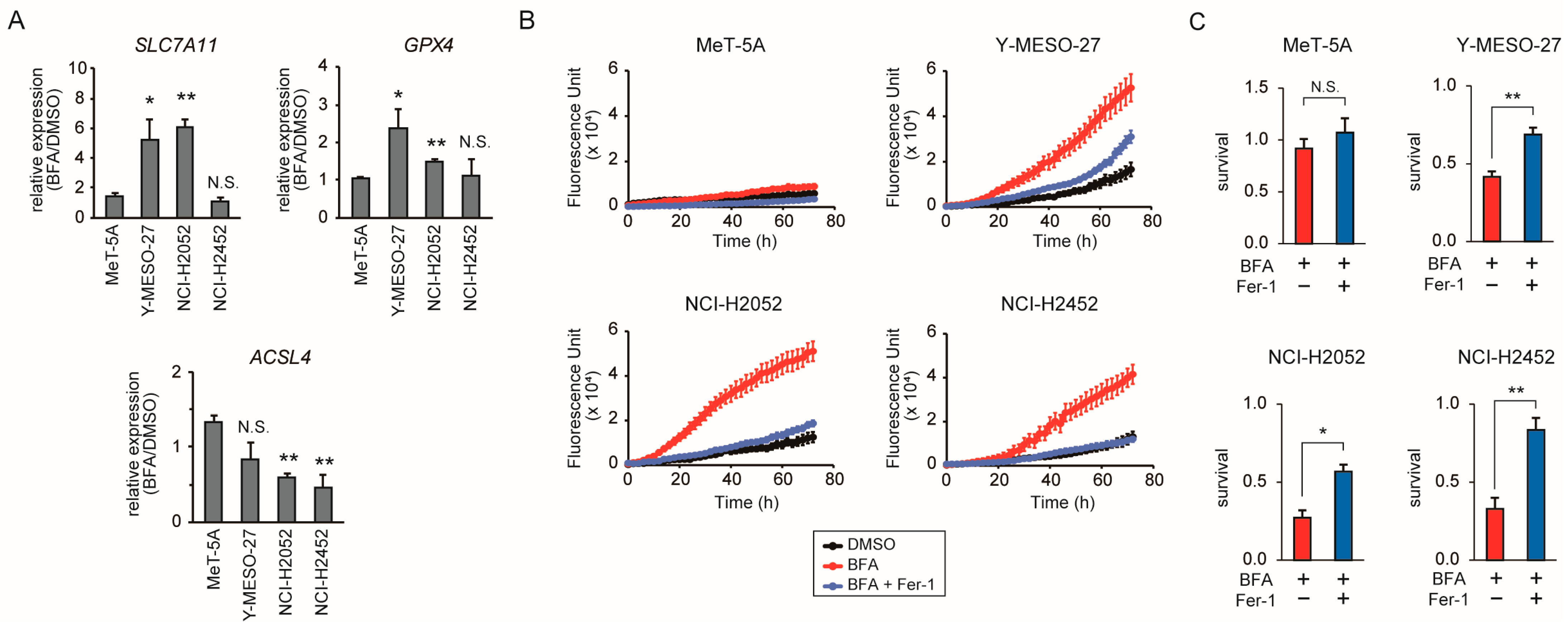

3.4. BFA Induces Ferroptosis in Mesothelioma Cells

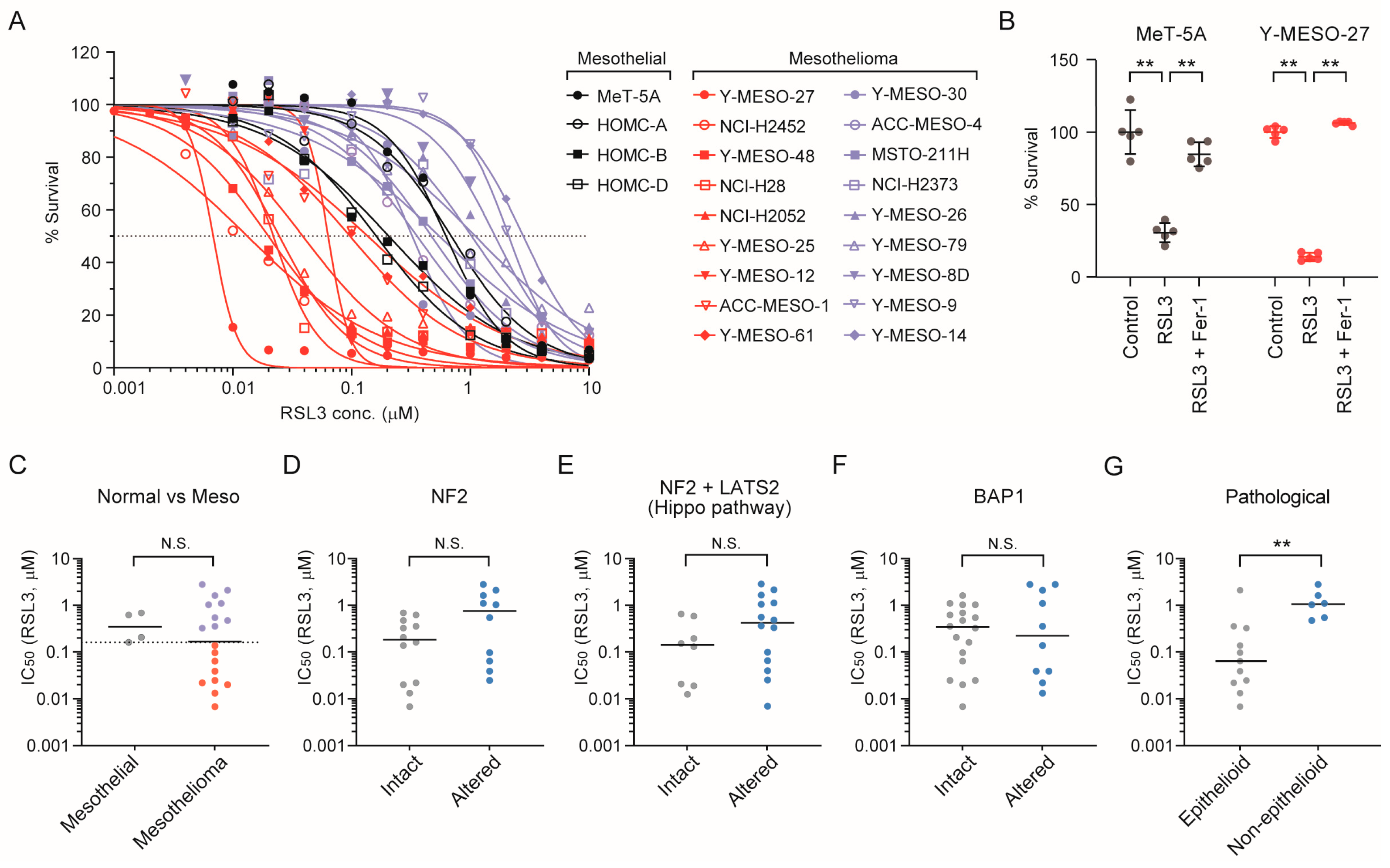

3.5. Epithelioid Mesothelioma Cell Lines Exhibit Intrinsic Sensitivity to the Ferroptosis Inducer RSL3

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACSL4 | Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 |

| BAP1 | BRCA1 associated protein 1 |

| BFA | Brefeldin A |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| GO | Gene ontology |

| GPX4 | Glutathione peroxidase 4 |

| IC50 | Half maximal inhibitory concentration |

| NF2 | Neurofibromin 2 |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated fatty acid |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RSL3 | RAS-selective lethal 3 |

| SLC7A11 | Solute carrier family 7 member 11 |

| UPR | Unfolded protein response |

Appendix A

| Cell Line | Cell Type | NF2 Alteration | LATS2 Alteration | BAP1 Alteration | Histology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACC-MESO-1 | Mesothelioma | Y | Epithelioid | ||

| ACC-MESO-4 | Mesothelioma | Y | Epithelioid | ||

| HOMC-A | Mesothelial | ||||

| HOMC-B | Mesothelial | ||||

| HOMC-D | Mesothelial | ||||

| MeT-5A | Mesothelial | ||||

| MSTO-211H | Mesothelioma | Y | Non-epithelioid | ||

| NCI-H2052 | Mesothelioma | Y | Y | Epithelioid | |

| NCI-H2373 | Mesothelioma | Y | Non-epithelioid | ||

| NCI-H2452 | Mesothelioma | Y | Epithelioid | ||

| NCI-H28 | Mesothelioma | Y | Epithelioid | ||

| Y-MESO-8D | Mesothelioma | No exp. | Non-epithelioid | ||

| Y-MESO-14 | Mesothelioma | Y | Y | Y | Non-epithelioid |

| Y-MESO-25 | Mesothelioma | Y | Y | Epithelioid | |

| Y-MESO-26 | Mesothelioma | Y | Y | Non-epithelioid | |

| Y-MESO-27 | Mesothelioma | Y | Epithelioid | ||

| Y-MESO-30 | Mesothelioma | Y | Epithelioid | ||

| Y-MESO-48 | Mesothelioma | Unknown | |||

| Y-MESO-61 | Mesothelioma | Y | Epithelioid | ||

| Y-MESO-79 | Mesothelioma | Y | Y | Non-epithelioid |

References

- Li, W.Z.; Liang, H.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Lao, S.; Liang, W.; He, J. Global mortality burden of lung cancer and mesothelioma attributable to occupational asbestos exposure and the impact of national asbestos ban policies: A population-based study, 1990–2021. BMJ Public Health 2025, 3, e001717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardillo, G.; Waller, D.; Tenconi, S.; Di Noia, V.; Ricciardi, S. Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: A 2025 Update. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennell, D.A.; Sekido, Y.; Baas, P.; Husain, A.N.; Curioni-Fontecedro, A.; Lim, E.; Opitz, I.; Simone, C.B., 2nd; Brims, F.; Wong, M.C. Pleural mesothelioma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2025, 11, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klebe, S.; Judge, M.; Brcic, L.; Dacic, S.; Galateau-Salle, F.; Nicholson, A.G.; Roggli, V.; Nowak, A.K.; Cooper, W.A. Mesothelioma in the pleura, pericardium and peritoneum: Recommendations from the International Collaboration on Cancer Reporting (ICCR). Histopathology 2024, 84, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bueno, R.; Stawiski, E.W.; Goldstein, L.D.; Durinck, S.; De Rienzo, A.; Modrusan, Z.; Gnad, F.; Nguyen, T.T.; Jaiswal, B.S.; Chirieac, L.R.; et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis of malignant pleural mesothelioma identifies recurrent mutations, gene fusions and splicing alterations. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hmeljak, J.; Sanchez-Vega, F.; Hoadley, K.A.; Shih, J.; Stewart, C.; Heiman, D.; Tarpey, P.; Danilova, L.; Drill, E.; Gibb, E.A.; et al. Integrative Molecular Characterization of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 1548–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekido, Y.; Sato, T. NF2 alteration in mesothelioma. Front. Toxicol. 2023, 5, 1161995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quetel, L.; Meiller, C.; Assie, J.B.; Blum, Y.; Imbeaud, S.; Montagne, F.; Tranchant, R.; de Wolf, J.; Caruso, S.; Copin, M.C.; et al. Genetic alterations of malignant pleural mesothelioma: Association with tumor heterogeneity and overall survival. Mol. Oncol. 2020, 14, 1207–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedres, S.; Valdivia, A.; Iranzo, P.; Callejo, A.; Pardo, N.; Navarro, A.; Martinez-Marti, A.; Assaf-Pastrana, J.D.; Felip, E.; Garrido, P. Current State-of-the-Art Therapy for Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma and Future Options Centered on Immunotherapy. Cancers 2023, 15, 5787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, E.; Darlison, L.; Edwards, J.; Elliott, D.; Fennell, D.A.; Popat, S.; Rintoul, R.C.; Waller, D.; Ali, C.; Bille, A.; et al. Mesothelioma and Radical Surgery 2 (MARS 2): Protocol for a multicentre randomised trial comparing (extended) pleurectomy decortication versus no (extended) pleurectomy decortication for patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e038892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, E.; Opitz, I.; Woodard, G.; Bueno, R.; de Perrot, M.; Flores, R.; Gill, R.; Jablons, D.; Pass, H. A Perspective on the MARS2 Trial. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2025, 20, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelzang, N.J.; Rusthoven, J.J.; Symanowski, J.; Denham, C.; Kaukel, E.; Ruffie, P.; Gatzemeier, U.; Boyer, M.; Emri, S.; Manegold, C.; et al. Phase III Study of Pemetrexed in Combination With Cisplatin Versus Cisplatin Alone in Patients With Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 2125–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baas, P.; Scherpereel, A.; Nowak, A.K.; Fujimoto, N.; Peters, S.; Tsao, A.S.; Mansfield, A.S.; Popat, S.; Jahan, T.; Antonia, S.; et al. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab in unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma (CheckMate 743): A multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, A.K.; Lesterhuis, W.J.; Kok, P.S.; Brown, C.; Hughes, B.G.; Karikios, D.J.; John, T.; Kao, S.C.; Leslie, C.; Cook, A.M.; et al. Durvalumab with first-line chemotherapy in previously untreated malignant pleural mesothelioma (DREAM): A multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial with a safety run-in. Lancet. Oncol. 2020, 21, 1213–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertuccio, F.R.; Montini, S.; Fusco, M.A.; Di Gennaro, A.; Sciandrone, G.; Agustoni, F.; Galli, G.; Bortolotto, C.; Saddi, J.; Baietto, G.; et al. Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: From Pathophysiology to Innovative Actionable Targets. Cancers 2025, 17, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suraya, R.; Nagano, T.; Tachihara, M. Recent Advances in Mesothelioma Treatment: Immunotherapy, Advanced Cell Therapy, and Other Innovative Therapeutic Modalities. Cancers 2025, 17, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, A.; Rashid, A.A.; Moeed, A.; Tahir, M.J.; Khan, A.J.; Shrateh, O.N.; Ahmed, A. Safety and efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with pre-treated advanced stage malignant mesothelioma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, I.M.; Kolev, V.N.; Vidal, C.M.; Kadariya, Y.; Ring, J.E.; Wright, Q.; Weaver, D.T.; Menges, C.; Padval, M.; McClatchey, A.I.; et al. Merlin deficiency predicts FAK inhibitor sensitivity: A synthetic lethal relationship. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 237ra68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Sato, T.; Yokoi, K.; Sekido, Y. E-cadherin expression is correlated with focal adhesion kinase inhibitor resistance in Merlin-negative malignant mesothelioma cells. Oncogene 2017, 36, 5522–5531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, T.A.; Kwiatkowski, D.J.; Dagogo-Jack, I.; Offin, M.; Zauderer, M.G.; Kratzke, R.; Desai, J.; Body, A.; Millward, M.; Tolcher, A.W.; et al. YAP/TEAD inhibitor VT3989 in solid tumors: A phase 1/2 trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 4281–4290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akao, K.; Sato, T.; Mishiro-Sato, E.; Mukai, S.; Ghani, F.I.; Kondo-Ida, L.; Imaizumi, K.; Sekido, Y. TEAD-Independent Cell Growth of Hippo-Inactive Mesothelioma Cells: Unveiling Resistance to TEAD Inhibitor K-975 through MYC Signaling Activation. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2025, 24, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cragg, G.M.; Newman, D.J. Natural products: A continuing source of novel drug leads. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1830, 3670–3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Kim, Y.; Boo, H.J.; Yoon, D.; Cha, J.S.; Yoo, J. Natural Product-Derived Drugs: Structural Insights into Their Biological Mechanisms. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singleton, V.L.; Bohonos, N.; Ullstrup, A.J. Decumbin, a new compound from a species of Penicillium. Nature 1958, 181, 1072–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T.; Akao, K.; Sato, A.; Tsujimura, T.; Mukai, S.; Sekido, Y. Aberrant expression of NPPB through YAP1 and TAZ activation in mesothelioma with Hippo pathway gene alterations. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 13586–13598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaffl, M.W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, T.; Oda, K.; Yokota, S.; Takatsuki, A.; Ikehara, Y. Brefeldin A causes disassembly of the Golgi complex and accumulation of secretory proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 1988, 263, 18545–18552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippincott-Schwartz, J.; Yuan, L.C.; Bonifacino, J.S.; Klausner, R.D. Rapid redistribution of Golgi proteins into the ER in cells treated with brefeldin A: Evidence for membrane cycling from Golgi to ER. Cell 1989, 56, 801–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Alvear, D.; Harnoss, J.M.; Walter, P.; Ashkenazi, A. Homeostasis control in health and disease by the unfolded protein response. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2025, 26, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, P.; Ron, D. The unfolded protein response: From stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science 2011, 334, 1081–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetz, C.; Papa, F.R. The Unfolded Protein Response and Cell Fate Control. Mol. Cell 2018, 69, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, L.E.; Dixon, S.J. Regulation of ferroptosis by lipid metabolism. Trends Cell Biol. 2023, 33, 1077–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockwell, B.R. Ferroptosis turns 10: Emerging mechanisms, physiological functions, and therapeutic applications. Cell 2022, 185, 2401–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Stockwell, B.R.; Conrad, M. Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alborzinia, H.; Ignashkova, T.I.; Dejure, F.R.; Gendarme, M.; Theobald, J.; Wolfl, S.; Lindemann, R.K.; Reiling, J.H. Golgi stress mediates redox imbalance and ferroptosis in human cells. Commun. Biol. 2018, 1, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Minikes, A.M.; Gao, M.; Bian, H.; Li, Y.; Stockwell, B.R.; Chen, Z.N.; Jiang, X. Intercellular interaction dictates cancer cell ferroptosis via NF2-YAP signalling. Nature 2019, 572, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shi, J.; Liu, X.; Feng, L.; Gong, Z.; Koppula, P.; Sirohi, K.; Li, X.; Wei, Y.; Lee, H.; et al. BAP1 links metabolic regulation of ferroptosis to tumour suppression. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 1181–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Sato, M.; Mishima, E.; Sato, H.; Proneth, B.; Conrad, M. Sorafenib fails to trigger ferroptosis across a wide range of cancer cell lines. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Yu, Y.; Yin, G.; Xu, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhao, G.; Ni, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, B.; et al. Sulfasalazine promotes ferroptosis through AKT-ERK1/2 and P53-SLC7A11 in rheumatoid arthritis. Inflammopharmacology 2024, 32, 1277–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setayeshpour, Y.; Lee, Y.; Chi, J.T. Environmental Determinants of Ferroptosis in Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.W.; Amante, J.J.; Goel, H.L.; Mercurio, A.M. The α6β4 integrin promotes resistance to ferroptosis. J. Cell Biol. 2017, 216, 4287–4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Amjad, S.; Yun, H.; Mani, S.; de Perrot, M. A panel of emerging EMT genes identified in malignant mesothelioma. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappas, A.G.; Magkouta, S.; Pateras, I.S.; Skianis, I.; Moschos, C.; Vazakidou, M.E.; Psarra, K.; Gorgoulis, V.G.; Kalomenidis, I. Versican modulates tumor-associated macrophage properties to stimulate mesothelioma growth. Oncoimmunology 2019, 8, e1537427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, X.; Tang, J.; Qiu, X.; Nie, X.; Ou, S.; Wu, G.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, J. Ferroptosis: Emerging mechanisms, biological function, and therapeutic potential in cancer and inflammation. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sato, T.; Hasegawa, I.; Ikeda, H.; Ohshiro, T.; Kondo-Ida, L.; Mukai, S.; Ohte, S.; Maeda, T.; Sekido, Y. Epithelioid Mesothelioma Cells Exhibit Increased Ferroptosis Sensitivity Compared to Non-Epithelioid Mesothelioma Cells. Cancers 2025, 17, 3983. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243983

Sato T, Hasegawa I, Ikeda H, Ohshiro T, Kondo-Ida L, Mukai S, Ohte S, Maeda T, Sekido Y. Epithelioid Mesothelioma Cells Exhibit Increased Ferroptosis Sensitivity Compared to Non-Epithelioid Mesothelioma Cells. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):3983. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243983

Chicago/Turabian StyleSato, Tatsuhiro, Ikue Hasegawa, Haruna Ikeda, Taichi Ohshiro, Lisa Kondo-Ida, Satomi Mukai, Satoshi Ohte, Tohru Maeda, and Yoshitaka Sekido. 2025. "Epithelioid Mesothelioma Cells Exhibit Increased Ferroptosis Sensitivity Compared to Non-Epithelioid Mesothelioma Cells" Cancers 17, no. 24: 3983. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243983

APA StyleSato, T., Hasegawa, I., Ikeda, H., Ohshiro, T., Kondo-Ida, L., Mukai, S., Ohte, S., Maeda, T., & Sekido, Y. (2025). Epithelioid Mesothelioma Cells Exhibit Increased Ferroptosis Sensitivity Compared to Non-Epithelioid Mesothelioma Cells. Cancers, 17(24), 3983. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243983