Oncologic and Reproductive Outcomes After Fertility-Sparing Treatments for Endometrial Hyperplasia with Atypia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Objectives

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Eligibility Criteria, Information Sources, Search Strategy

3.2. Study Selection

3.3. Data Extraction

3.4. Assessment of Risk of Bias and Quality of the Evidence

3.5. Data Synthesis

4. Results

4.1. Study Selection

4.2. Study Characteristics

4.3. Risk of Bias of Included Studies

4.4. Synthesis of Results

4.4.1. Complete Response Rates

4.4.2. Oral Progestins Alone

4.4.3. LNG-IUD Alone

4.4.4. Combination Therapies with HR

4.4.5. Combined Methods of Conservative Therapies

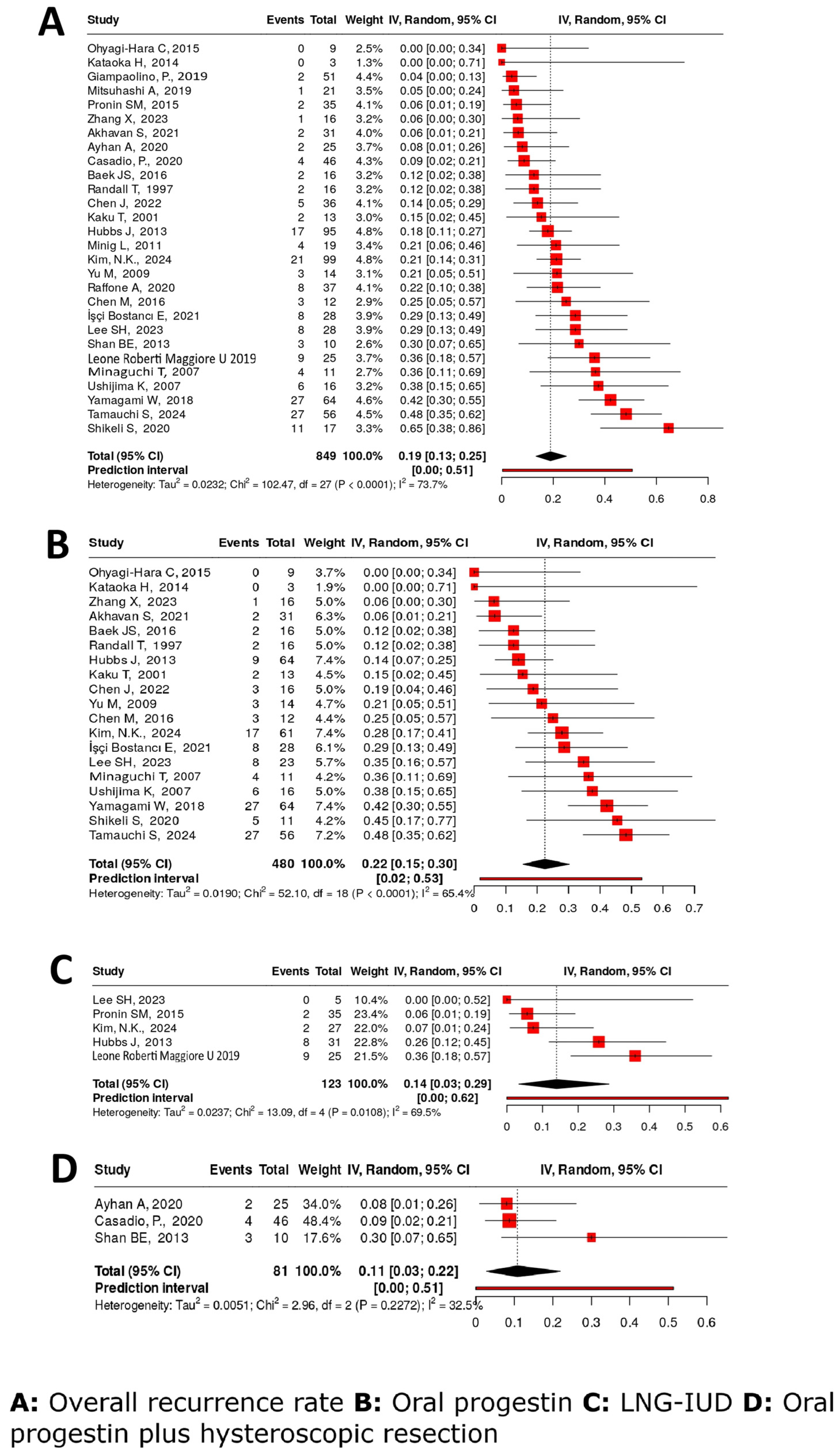

4.4.6. Recurrence Rate

4.4.7. Pregnancy Rate

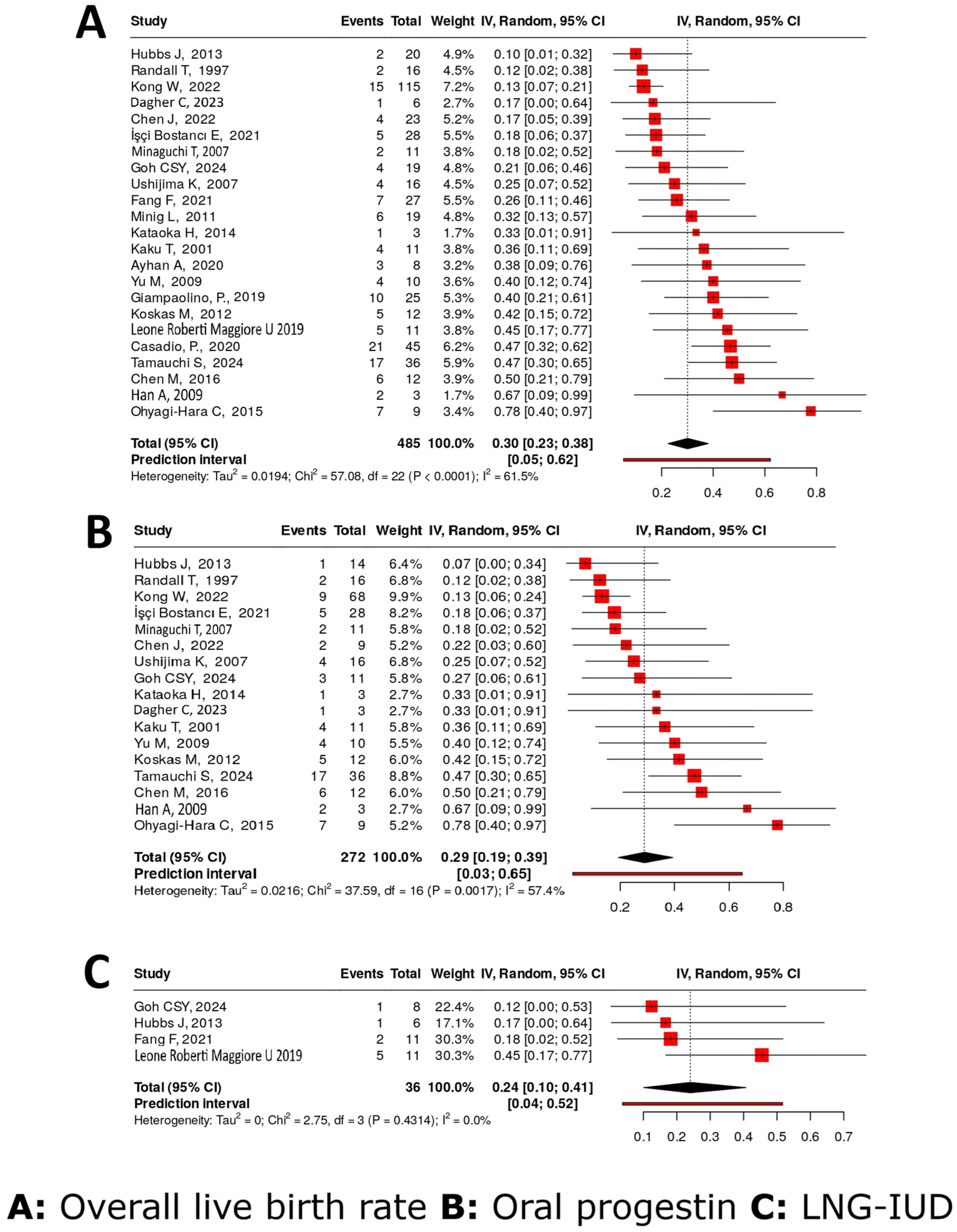

4.4.8. Live Birth Rates

4.4.9. Partial Response Rate

4.4.10. No-Response Rate

4.4.11. Weighted Mean Time to CR and Weighted Mean Time to Recurrence

4.5. Assessing the Certainty of Evidence

4.6. Influencing Factors

4.7. Assessment of Reporting Bias

4.8. Sensitivity Analysis

5. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AEH | Atypical endometrial hyperplasia |

| CR | Complete response |

| EC | Endometrial carcinoma |

| EIN | Endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia |

| FST | Fertility-sparing statement |

| GnRHa | Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue |

| HR | Hysteroscopic resection |

| LBR | Live birth rate |

| LNG-IUD | Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device |

| MA | Megestrol acetate |

| MPA | Medroxyprogesterone acetate |

| NR | No response |

| OP | Oral progestin |

| PR | Partial response |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| RR | Recurrence rate |

References

- Oda, K.; Koga, K.; Hirata, T.; Maruyama, M.; Ikemura, M.; Matsumoto, Y.; Nagasaka, K.; Adachi, K.; Mori-Uchino, M.; Sone, K. Risk of endometrial cancer in patients with a preoperative diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia treated with total laparoscopic hysterectomy. Gynecol. Minim. Invasive Ther. 2016, 5, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, A.-J.; Bing, R.-S.; Ding, D.-C. Endometrial atypical hyperplasia and risk of endometrial cancer. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nees, L.K.; Heublein, S.; Steinmacher, S.; Juhasz-Böss, I.; Brucker, S.; Tempfer, C.B.; Wallwiener, M. Endometrial hyperplasia as a risk factor of endometrial cancer. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 306, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novetsky, A.P.; Valea, F. Management of Endometrial Intraepithelial Neoplasia or Atypical Endometrial Hyperplasia. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 142, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-F.; Fan, Y.; Mu, Y.; Li, J.-K. Efficacy of oral medications or intrauterine device-delivered progestin in patients with endometrial hyperplasia with or without atypia: A network meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uccella, S.; Zorzato, P.C.; Dababou, S.; Bosco, M.; Torella, M.; Braga, A.; Frigerio, M.; Gardella, B.; Cianci, S.; Lagana, A.S. Conservative management of atypical endometrial hyperplasia and early endometrial cancer in childbearing age women. Medicina 2022, 58, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushijima, K.; Tsuda, N.; Yamagami, W.; Mitsuhashi, A.; Mikami, M.; Yaegashi, N.; Enomoto, T. Trends and characteristics of fertility-sparing treatment for atypical endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer in Japan: A survey by the Gynecologic Oncology Committee of the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2023, 34, e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodolakis, A.; Scambia, G.; Planchamp, F.; Acien, M.; Di Spiezio Sardo, A.; Farrugia, M.; Grynberg, M.; Pakiz, M.; Pavlakis, K.; Vermeulen, N. ESGO/ESHRE/ESGE Guidelines for the fertility-sparing treatment of patients with endometrial carcinoma. Hum. Reprod. Open 2023, 2023, hoac057. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, S.; Molberg, K.; Castrillon, D.H.; Lucas, E.; Chen, H. Biomarkers in the Diagnosis of Endometrial Precancers. Molecular Characteristics, Candidate Immunohistochemical Markers, and Promising Results of Three-Marker Panel: Current Status and Future Directions. Cancers 2024, 16, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keszthelyi, M.; Sebok, P.; Vida, B.; Szabó, V.; Kalas, N.; Várbíró, S.; Lőczi, L.; Ács, N.; Merkely, P.; Tóth, R.; et al. Efficacy of Fertility-Sparing Treatments for Early-Stage Endometrial Cancer—Oncologic and Reproductive Outcomes: Protocol of a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Life 2025, 15, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; Volume 4, p. 14651858. [Google Scholar]

- Schünemann, H.; Brożek, J.; Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A. GRADE Handbook for Grading Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations [Internet]. 2013. GRADE Working Group. Available online: https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Yang, B.Y.; Gulinazi, Y.; Du, Y.; Ning, C.C.; Cheng, Y.L.; Shan, W.W.; Luo, X.Z.; Zhang, H.W.; Zhu, Q.; Ma, F.H.; et al. Metformin plus megestrol acetate compared with megestrol acetate alone as fertility-sparing treatment in patients with atypical endometrial hyperplasia and well-differentiated endometrial cancer: A randomised controlled trial. Bjog 2020, 127, 848–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, C.S.Y.; Loh, M.J.M.; Lim, W.W.; Ang, J.X.; Nadarajah, R.; Yong, T.T.; Tong, P.; Yeo, Y.C.; Phoon, J.W.L. A multi-centre randomised controlled trial comparing megestrol acetate to levonorgestrel-intrauterine system in fertility sparing treatment of atypical endometrial hyperplasia. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2024, 41, 2485–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ushijima, K.; Yahata, H.; Yoshikawa, H.; Konishi, I.; Yasugi, T.; Saito, T.; Nakanishi, T.; Sasaki, H.; Saji, F.; Iwasaka, T. Multicenter phase II study of fertility-sparing treatment with medroxyprogesterone acetate for endometrial carcinoma and atypical hyperplasia in young women. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 2798–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostanci, E.İ.; Durmuş, Y.; Çöteli, S.A.D.; Kayikçioğlu, F.; Boran, N. Outcomes of the conservative management of the patients with endometrialintraepithelial neoplasia/endometrial cancer: Wait or treat! Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 51, 2066–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayhan, A.; Tohma, Y.A.; Tunc, M. Fertility preservation in early-stage endometrial cancer and endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia: A single-center experience. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 59, 415–419. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta-Torres, S.; Murdock, T.; Matsuno, R.; Beavis, A.L.; Stone, R.L.; Wethington, S.L.; Levinson, K.; Grumbine, F.; Ferriss, J.S.; Tanner, E.J. The addition of metformin to progestin therapy in the fertility-sparing treatment of women with atypical hyperplasia/endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia or endometrial cancer: Little impact on response and low live-birth rates. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 157, 348–356. [Google Scholar]

- Ciccone, M.A.; Whitman, S.A.; Conturie, C.L.; Brown, N.; Dancz, C.E.; Özel, B.; Matsuo, K. Effectiveness of progestin-based therapy for morbidly obese women with complex atypical hyperplasia. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2019, 299, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Jin, Y.; Li, Y.; Bi, Y.; Shan, Y.; Pan, L. Oncologic and reproductive outcomes after fertility-sparing management with oral progestin for women with complex endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2016, 132, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronin, S.M.; Novikova, O.V.; Andreeva, J.Y.; Novikova, E.G. Fertility-sparing treatment of early endometrial cancer and complex atypical hyperplasia in young women of childbearing potential. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2015, 25, 1010–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, B.; Ren, Y.; Sun, J.; Tu, X.; Jiang, Z.; Ju, X.; Zang, R.; Wang, H. A prospective study of fertility-sparing treatment with megestrol acetate following hysteroscopic curettage for well-differentiated endometrioid carcinoma and atypical hyperplasia in young women. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2013, 288, 1115–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Yang, J.; Wu, M.; Lang, J.; Huo, Z.; Shen, K. Fertility-preserving treatment in young women with well-differentiated endometrial carcinoma and severe atypical hyperplasia of endometrium. Fertil. Steril. 2009, 92, 2122–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N.K.; Choi, C.H.; Seong, S.J.; Lee, J.-M.; Lee, B.; Kim, K. Treatment outcomes according to various progestin treatment strategies in patients with atypical hyperplasia/endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia–Multicenter retrospective study (KGOG2033). Gynecol. Oncol. 2024, 183, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shikeli, S.; Gowri, V.; Al Rawahi, T. Fertility-sparing treatment in young women with atypical endometrial hyperplasia and low-grade endometrial cancer: A Tertiary Center experience. JBRA Assist. Reprod. 2020, 24, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Cao, D.; Yang, J.; Yu, M.; Zhou, H.; Cheng, N.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, P.; Shen, K. Fertility-sparing treatment for endometrial cancer or atypical endometrial hyperplasia patients with obesity. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 812346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhavan, S.; Sabet, F.; Mousavi, A.-S.; Gilani, M.M.; Hasani, S.S. Effectiveness of megestrol for the treatment of patients with atypical endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinoma (Stage IA, well differentiated). J. Res. Pharm. Pract. 2021, 10, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Xu, H.; Wu, L.; Hu, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C. LNG-IUS combined with progesterone ameliorates endometrial thickness and pregnancy outcomes of patients with early-stage endometrial cancer or atypical hyperplasia. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2021, 13, 5412–5419. [Google Scholar]

- Novikova, O.V.; Nosov, V.B.; Panov, V.A.; Novikova, E.G.; Krasnopolskaya, K.V.; Andreeva, Y.Y.; Shevchuk, A.S. Live births and maintenance with levonorgestrel IUD improve disease-free survival after fertility-sparing treatment of atypical hyperplasia and early endometrial cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 161, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohyagi-Hara, C.; Sawada, K.; Aki, I.; Mabuchi, S.; Kobayashi, E.; Ueda, Y.; Yoshino, K.; Fujita, M.; Tsutsui, T.; Kimura, T. Efficacies and pregnant outcomes of fertility-sparing treatment with medroxyprogesterone acetate for endometrioid adenocarcinoma and complex atypical hyperplasia: Our experience and a review of the literature. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2015, 291, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minig, L.; Franchi, D.; Boveri, S.; Casadio, C.; Bocciolone, L.; Sideri, M. Progestin intrauterine device and GnRH analogue for uterus-sparing treatment of endometrial precancers and well-differentiated early endometrial carcinoma in young women. Ann. Oncol. 2011, 22, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaku, T.; Yoshikawa, H.; Tsuda, H.; Sakamoto, A.; Fukunaga, M.; Kuwabara, Y.; Hataeg, M.; Kodama, S.; Kuzuya, K.; Sato, S. Conservative therapy for adenocarcinoma and atypical endometrial hyperplasia of the endometrium in young women: Central pathologic review and treatment outcome. Cancer Lett. 2001, 167, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsuhashi, A.; Habu, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Kawarai, Y.; Ishikawa, H.; Usui, H.; Shozu, M. Long-term outcomes of progestin plus metformin as a fertility-sparing treatment for atypical endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer patients. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2019, 30, e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouasti, S.; Bucau, M.; Larouzee, E.; Clement De Givry, S.; Chabbert-Buffet, N.; Koskas, M. Prospective study of fertility-sparing treatment with chlormadinone acetate for endometrial carcinoma and atypical hyperplasia in young women. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 157, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casadio, P.; La Rosa, M.; Alletto, A.; Magnarelli, G.; Arena, A.; Fontana, E.; Fabbri, M.; Giovannico, K.; Virgilio, A.; Raimondo, D. Fertility sparing treatment of endometrial cancer with and without initial infiltration of myometrium: A single center experience. Cancers 2020, 12, 3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giampaolino, P.; Sardo, A.D.S.; Mollo, A.; Raffone, A.; Travaglino, A.; Boccellino, A.; Zizolfi, B.; Insabato, L.; Zullo, F.; De Placido, G. Hysteroscopic endometrial focal resection followed by levonorgestrel intrauterine device insertion as a fertility-sparing treatment of atypical endometrial hyperplasia and early endometrial cancer: A retrospective study. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2019, 26, 648–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamauchi, S.; Nakagawa, A.; Yoshida, K.; Yoshihara, M.; Yokoi, A.; Yoshikawa, N.; Niimi, K.; Kajiyama, H. Update on the oncologic and obstetric outcomes of medroxyprogesterone acetate treatment for atypical endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2024, 50, 1614–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Ng, C.; Ling, P.W.; Goh, C.; Lin, X.H.; Mathur, M.; Chin, F.H.X. Medical Management of Atypical Endometrial Hyperplasia: Oncological and Reproductive Outcomes at a Tertiary Center in Singapore. Cureus 2023, 15, e42685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiore, U.L.R.; Martinelli, F.; Dondi, G.; Bogani, G.; Chiappa, V.; Evangelista, M.T.; Liberale, V.; Ditto, A.; Ferrero, S.; Raspagliesi, F. Efficacy and fertility outcomes of levonorgestrel-releasing intra-uterine system treatment for patients with atypical complex hyperplasia or endometrial cancer: A retrospective study. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2019, 30, e57. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Xie, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, Q.; Du, Y.; Luo, X.; Chen, X. Insulin resistance and overweight prolonged fertility-sparing treatment duration in endometrial atypical hyperplasia patients. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 29, e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.S.; Lee, W.H.; Kang, W.D.; Kim, S.M. Fertility-preserving treatment in complex atypical hyperplasia and early endometrial cancer in young women with oral progestin: Is it effective? Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2016, 59, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbs, J.L.; Saig, R.M.; Abaid, L.N.; Bae-Jump, V.L.; Gehrig, P.A. Systemic and local hormone therapy for endometrial hyperplasia and early adenocarcinoma. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 121, 1172–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kataoka, H.; Mori, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Sawada, M.; Kuroboshi, H.; Tatsumi, H.; Iwasaku, K.; Kitawaki, J. Outcome of fertility-sparing treatment with medroxyprogesterone acetate for atypical hyperplasia and endometrial carcinoma in young Japanese women. Eur. J. Gynaec. Oncol. 2014, 35, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, W.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, N.; Wu, X.; Zhao, X.; Yan, L. A prospective cohort study of metformin as an adjuvant therapy for infertile women with endometrial complex hyperplasia/complex atypical hyperplasia and their subsequent assisted reproductive technology outcomes. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 849794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownfoot, F.C.; Hickey, M.; Ang, W.C.; Arora, V.; McNally, O. Complex atypical hyperplasia of the endometrium: Differences in outcome following conservative management of pre-and postmenopausal women. Reprod. Sci. 2014, 21, 1244–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagher, C.; Manning-Geist, B.; Ellenson, L.H.; Weigelt, B.; Rios-Doria, E.; Barry, D.; Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Leitao, M.M., Jr.; Mueller, J.J. Molecular subtyping in endometrial cancer: A promising strategy to guide fertility preservation. Gynecol. Oncol. 2023, 179, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, A.R.; Kwon, Y.-S.; Kim, D.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, Y.; Nam, J. Pregnancy outcomes using assisted reproductive technology after fertility-preserving therapy in patients with endometrial adenocarcinoma or atypical complex hyperplasia. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2009, 19, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskas, M.; Azria, E.; Walker, F.; Luton, D.; Madelenat, P.; Yazbeck, C. Progestin treatment of atypical hyperplasia and well-differentiated adenocarcinoma of the endometrium to preserve fertility. Anticancer Res. 2012, 32, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar]

- Mentrikoski, M.J.; Shah, A.A.; Hanley, K.Z.; Atkins, K.A. Assessing endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma treated with progestin therapy. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2012, 138, 524–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, N.; Broaddus, R.R.; Urbauer, D.L.; Balakrishnan, N.; Milbourne, A.; Schmeler, K.M.; Meyer, L.A.; Soliman, P.T.; Lu, K.H.; Ramirez, P.T. Treatment of low-risk endometrial cancer and complex atypical hyperplasia with the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 131, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffone, A.; Travaglino, A.; Flacco, M.E.; Iasevoli, M.; Mollo, A.; Guida, M.; Insabato, L.; Di Spiezio Sardo, A.; Carugno, J.; Zullo, F. Clinical predictive factors of response to treatment in patients undergoing conservative management of atypical endometrial hyperplasia and early endometrial cancer. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2021, 10, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, T.C.; Kurman, R.J. Progestin treatment of atypical hyperplasia and well-differentiated carcinoma of the endometrium in women under age 40. Obstet. Gynecol. 1997, 90, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, E.; Maniglio, P.; Frega, A.; Marci, R.; Caserta, D.; Moscarini, M. Fertility-sparing treatment of endometrial cancer precursors among young women: A reproductive point of view. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2012, 16, 1934–1937. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, D.T.; Bristow, R.E.; Kurman, R.J. Histologic alterations in endometrial hyperplasia and well-differentiated carcinoma treated with progestins. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2007, 31, 988–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamagami, W.; Susumu, N.; Makabe, T.; Sakai, K.; Nomura, H.; Kataoka, F.; Hirasawa, A.; Banno, K.; Aoki, D. Is repeated high-dose medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) therapy permissible for patients with early stage endometrial cancer or atypical endometrial hyperplasia who desire preserving fertility? J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 29, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, D.; Zhao, X.; Wang, C.; He, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Shen, D. Application of molecular classification to guiding fertility-sparing therapy for patients with endometrial cancer or endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2023, 241, 154278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minaguchi, T.; Nakagawa, S.; Takazawa, Y.; Nei, T.; Horie, K.; Fujiwara, T.; Osuga, Y.; Yasugi, T.; Kugu, K.; Yano, T.; et al. Combined phospho-Akt and PTEN expressions associated with post-treatment hysterectomy after conservative progestin therapy in complex atypical hyperplasia and stage Ia, G1 adenocarcinoma of the endometrium. Cancer Lett. 2007, 248, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, W.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Gu, C.; Ning, C.; Luo, X.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, X. Conservative therapy with metformin plus megestrol acetate for endometrial atypical hyperplasia. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 25, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signorelli, M.; Caspani, G.; Bonazzi, C.; Chiappa, V.; Perego, P.; Mangioni, C. Fertility-sparing treatment in young women with endometrial cancer or atypical complex hyperplasia: A prospective single-institution experience of 21 cases. Bjog 2009, 116, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Seong, S.J.; Kim, J.W.; Jeon, S.; Choi, H.S.; Lee, I.H.; Lee, J.H.; Ju, W.; Song, E.S.; Park, H.; et al. Management of Endometrial Hyperplasia With a Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intrauterine System: A Korean Gynecologic-Oncology Group Study. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2016, 26, 711–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Guo, T.; Cui, R.; Feng, Y.; Bai, H.; Zhang, Z. Weight control is vital for patients with early-stage endometrial cancer or complex atypical hyperplasia who have received progestin therapy to spare fertility: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 4005–4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, J.; Yan, Y.; Tian, L.; Chen, L.; Zheng, X.; Sun, Y.; Tian, W.; Xue, F.; Wang, Y. Oncological and reproductive outcomes of endometrial atypical hyperplasia and endometrial cancer patients undergoing conservative therapy with hysteroscopic resection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2024, 103, 1498–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhang, W.; Feng, L.; Gao, W. Comparison of fertility-sparing treatments in patients with early endometrial cancer and atypical complex hyperplasia: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Medicine 2017, 96, e8034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallos, I.D.; Yap, J.; Rajkhowa, M.; Luesley, D.M.; Coomarasamy, A.; Gupta, J.K. Regression, relapse, and live birth rates with fertility-sparing therapy for endometrial cancer and atypical complex endometrial hyperplasia: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 207, 266.e1–266.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, F.A.; Uccella, S.; Franchi, M.; Scambia, G.; Fanfani, F.; Fagotti, A.; Pavone, M.; Raspagliesi, F.; Bogani, G. Performance of molecular classification in predicting oncologic outcomes of fertility-sparing treatment for atypical endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2025, 35, 100016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, F.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y. Progestin plus metformin improves outcomes in patients with endometrial hyperplasia and early endometrial cancer more than progestin alone: A meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1139858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Factor, P.A.A.; Pasamba, K.C. Metformin as an Adjunct to Progestin Therapy in Endometrial Hyperplasia and Early-Stage Endometrial Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Acta Medica Philipp. 2024, 58, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamyan, L.; Pivazyan, L.; Isaeva, S.; Shapovalenko, R.; Zakaryan, A. Metformin and progestins in women with atypical hyperplasia or endometrial cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 309, 2289–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rocco, S.; Buca, D.; Oronzii, L.; Petrillo, M.; Fanfani, F.; Nappi, L.; Liberati, M.; D’Antonio, F.; Scambia, G.; Leombroni, M. Reproductive and pregnancy outcomes of fertility-sparing treatments for early-stage endometrial cancer or atypical hyperplasia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2022, 273, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Li, H.; Hu, R.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Gu, L. Fertility-preserving treatment in young women with grade 1 presumed stage IA endometrial adenocarcinoma: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2018, 28, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Li, T. Effects of hysteroscopic surgery combined with progesterone therapy on fertility and prognosis in patients with early endometrial cancer and atypical endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia: A meta-analysis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 309, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Ferris, J.S.; Chen, L.; Dioun, S.; Usseglio, J.; Matsuo, K.; Xu, X.; Hershman, D.L.; Wright, J.D. Fertility-preserving treatment for stage IA endometrial cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 231, 599–610.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedrick Ellenson, L.; Ronnett, B.M.; Kurman, R.J. Precursors of endometrial carcinoma. In Blaustein’s Pathology of the Female Genital Tract; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 439–472. [Google Scholar]

- Bilir, E.; Kacperczyk-Bartnik, J.; Bizzarri, N.; Kahramanoğlu, İ. Current practice with operative hysteroscopy for fertility preservation in endometrial cancer and endometrial premalignancies. Arch. Gynecol. Obs. 2024, 309, 2267–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travaglino, A.; Raffone, A.; Saccone, G.; Mascolo, M.; Guida, M.; Mollo, A.; Insabato, L.; Zullo, F. Congruence Between 1994 WHO Classification of Endometrial Hyperplasia and Endometrial Intraepithelial Neoplasia System. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2020, 153, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emons, G.; Beckmann, M.W.; Schmidt, D.; Mallmann, P. New WHO Classification of Endometrial Hyperplasias. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2015, 75, 135–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baak, J.P.; Mutter, G.L. EIN and WHO94. J. Clin. Pathol. 2005, 58, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | No. of Patients | Age 1 | BMI 2 | Therapy 3 | Regimen 4 | CR 5 | Recurrence Rate 6 | Pregnancy Rate 7 | Live Birth Rate 8 | Partial Response 9 | No Response 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ushijima K 2007 [16] | 17 | 31.7 M | 22.8 M | Oral | MPA 600 mg | 16/17 | 6/16 | 7/16 | 4/16 | 1/17 | N/A |

| Bostancı İ E 2021 [17] | 32 | 43.78 M | 32.85 M | Oral | MA 80–480 mg | 28/32 | 8/28 | 7/28 | 5/28 | N/A | 4/32 |

| Ayhan A 2020 [18] | 27 | 34 (20–43) MD | 28.8 (22–41) m | Oral + HR | MA 160 mg | 25/27 | 2/25 | 4/8 | 3/8 | N/A | 2/27 |

| Acosta-Torres S 2020 [19] | 54 | 37.7 MD | 35 m | Oral | MA 80–160 mg, MPA 10–40 mg | 26/33 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 37.7 MD | 35 m | Oral + Met | MA 80–160 mg, MPA 10–40 mg, Met 500–1000 mg | 15/21 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Yang BY 2020 [14] | 112 | N/A | N/A | Oral | MA 160 mg | 39/57 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| N/A | N/A | Oral + Met | MA 160 mg, Met 1500 mg | 40/55 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Ciccone MA 2019 [20] | 117 | 35 M | 40.2 M | Oral | MA, MPA | 39/103 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 35 M | 40.2 M | IUD | LNG | 10/14 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Chen M 2016 [21] | 16 | 32 (21–41) MD | N/A | Oral | MPA 250–500 mg | 12/16 | 3/12 | 9/12 | 6/12 | 1/16 | 3/16 |

| Pronin SM 2015 [22] | 38 | 33 (28–42) MD | N/A | IUD | LNG | 35/38 | 2/35 | N/A | N/A | 0/38 | 3/38 |

| Shan BE 2013 [23] | 12 | 25 M | 29.25 (18–38) M | Oral + HR | MA 160 mg | 10/12 | 3/10 | N/A | N/A | 0/12 | 2/12 |

| Yu M 2009 [24] | 17 | 29.9 M | N/A | Oral | MPA 100–500 mg | 14/17 | 3/14 | 4/10 | 4/10 | 3/17 | N/A |

| Kim N.K. 2024 [25] | 124 | 35.2 M | 26.8 M | Oral | MA 40–400 mg, MPA 10–500 mg | 61/74 | 17/61 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 34.2 M | 28.3 M | IUD | LNG | 27/37 | 2/27 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| 34.5 M | 26.9 M | Oral + IUD | MA 40–400 mg, MPA 10–500 mg, LNG | 11/13 | 2/11 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Shikeli S 2020 [26] | 18 | 31 MD | 33 m | Oral | MA 160 mg | 11/11 | 5/11 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 31 MD | 33 m | Oral + IUD | MA 160 mg, LNG | 6/7 | 6/6 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Chen J 2022 [27] | 40 | 32 (21–42) MD | 33.5 m | Oral | MA 160 mg, MPA 500 mg | 16/19 | 3/16 | 3/9 | 2/9 | N/A | N/A |

| 32 (21–42) MD | 33.5 m | IUD + GnRHa | LNG, GnRHa | 20/21 | 2/20 | 4/14 | 2/14 | N/A | N/A | ||

| Akhavan S 2021 [28] | 50 | 32.4 M | 30 M | Oral | MA 160–320 mg | 31/50 | 2/31 | 8/25 | N/A | 6/50 | 13/50 |

| Fang F 2021 [29] | 47 | 30 M | N/A | IUD | LNG | 11/20 | N/A | 5/11 | 2/11 | 3/20 | 6/20 |

| 30 | N/A | Oral + IUD | LNG, MPA 10 mg | 23/27 | N/A | 12/16 | 5/16 | 2/27 | 2/27 | ||

| Novikova OV 2021 [30] | 228 | 34 (20–46) MD | 25.5 m | Oral | MPA 500 mg | 34/37 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 34 (20–46) MD | 25.5 m | IUD | LNG | 166/169 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| 34 (20–46) MD | 25.5 m | IUD + GnRHa | LNG, Goserelin 3.6 mg | 19/20 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Ohyagi-Hara C 2015 [31] | 11 | 34.2 (22–43) M | 24 (16–47.3) M | Oral | MPA 400–600 mg | 9/11 | 0/9 | 5/9 | 5/9 | N/A | N/A |

| Minig L 2011 [32] | 20 | 34 (22–40) M | 21 (17–41) M | IUD + GnRHa | LNG, GnRHa | 19/20 | 4/19 | 8/19 | 6/19 | N/A | N/A |

| Kaku T 2001 [33] | 18 | 29.3 (21–42) M | N/A | Oral | MPA 100–800 mg | 13/18 | 2/13 | 5/11 | 4/11 | 2/18 | 3/18 |

| Mitsuhashi A 2019 [34] | 21 | 35 (26–44) MD | 31 (15.4–50.8) m | Oral + Met | MPA 400–600 mg, Met 750–2250 mg | 21/21 | 1/21 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Ouasti S 2022 [35] | 64 | 35 (19–47) MD | 28 (6–123) m | Oral | Chlormadinone acetate | 56/64 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 6/64 | 2/64 |

| Casadio P 2020 [36] | 46 | 32.2 M | 27 M | Oral + HR | MA 160 mg | 46/46 | 4/46 | 31/45 | 21/45 | N/A | N/A |

| Giampaolino P 2019 [37] | 55 | 25.9 M | 35.1 M | IUD + HR | LNG | 51/55 | 2/51 | 10/25 | 10/25 | 2/55 | 2/55 |

| Goh CSY 2024 [15] | 36 | 32 MD | 32.8 (25.1–50.8) m | Oral | MA 160 mg | 16/18 | N/A | 6/11 | 3/11 | N/A | 2/18 |

| 32 (23–40) MD | 35.5 (20.0–55.9) m | IUD | LNG | 16/18 | N/A | 2/8 | 1/8 | 0/18 | 2/18 | ||

| Tamauchi S 2024 [38] | 56 | 34.2(19.4–44.6) MD | 24.5(18–45) m | Oral | MPA 600 mg | 53/56 | 27/56 | 26/36 | 17/36 | N/A | 3/56 |

| Lee SH 2023 [39] | 42 | 42.32 M | 30.44 M | Oral | Norethisterone 20–40 mg Dydrogesterone 20 mg Megestrol acetate 160–320 mg | 23/37 | 8/23 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 34.2 M | 36.4 M | IUD | LNG | 5/5 | 0/5 | N/A | N/A | 0/5 | N/A | ||

| Leone Roberti Maggiore U 2019 [40] | 28 | 35.1 M | 25 M | IUD | LNG | 25/28 | 9/25 | 6/11 | 5/11 | 2/28 | 1/28 |

| Yang B 2018 [41] | 151 | 33.0 (21–54) MD | 24.23 (17.07–37.95) m | Oral | MA 160 mg | 78/82 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 33.0 (21–54) MD | 24.23 (17.07–37.95) m | Oral + Met | MA 160 mg, Met 1500 mg | 63/69 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Baek JS 2016 [42] | 18 | 33 MD | 23.1 m | Oral | MA 80–160 mg | 16/18 | 2/16 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Hubbs J 2013 [43] | 114 | 45 (25–83) MD | 36.1 (16.9–92.9) m | Oral | N/A | 64/79 | 9/64 | 1/14 | 1/14 | N/A | N/A |

| 47 (29–92) MD | 50.8 (25–70) m | IUD | LNG | 31/35 | 8/31 | 1/6 | 1/6 | N/A | N/A | ||

| Kataoka H 2014 [44] | 3 | 34 M | 23 M | Oral | MPA 400–600 mg | 3/3 | 0/3 | 1/3 | 1/3 | N/A | N/A |

| Kong W 2022 [45] | 219 | 33 M | 26.33 M | Oral | MA 160 mg, MPA 250–500 mg | 116/138 | N/A | 14/68 | 9/68 | N/A | N/A |

| 32 M | 27 M | Oral + Met | MA 160 mg, MPA 250–500 mg, Met 500 mg | 76/81 | N/A | 10/47 | 6/47 | N/A | N/A | ||

| Brownfoot F 2014 [46] | 42 | 37 M | 35 M | Oral | MPA | 24/32 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 37 M | 35 M | IUD | LNG | 8/10 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Dagher C 2023 [47] | 6 | 36.9 M | 32.4 | Oral | MA 160–320 mg | 1/3 | N/A | 1/3 | 1/3 | N/A | N/A |

| 37.7 M | 40.7 M | Oral + IUD | MA 160–320 mg, LNG | 2/3 | N/A | 0/3 | 0/3 | N/A | N/A | ||

| Han A 2009 [48] | 3 | 32.7 M | N/A | Oral | MA 80–160 mg, MPA 20–1000 mg | 3/3 | N/A | 2/3 | 2/3 | N/A | N/A |

| Koskas M 2012 [49] | 14 | 34.5 M | N/A | Oral | N/A, MPA, MA, CA | 12/14 | N/A | 6/12 | 5/12 | N/A | N/A |

| Mentrikoski J 2012 [50] | 6 | 28 (25–29) MD | N/A | Oral | N/A | 3/6 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1/6 | 2/6 |

| Pal N 2018 [51] | 15 | 45.6 (18.5–85.2) MD | 45 (20–74) m | IUD | LNG | 11/15 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1/15 | 3/15 |

| Raffone A 2021 [52] | 37 | 36.1 (5.9) M | 27.9 (7.6) M | IUD + HR | LNG | 37/37 | 8/37 | 10/37 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Randall T 1997 [53] | 17 | 34.3 (25–39) MD | N/A | Oral | MA 40–160 mg, MPA 10 mg | 16/17 | 2/16 | 2/16 | 2/16 | N/A | 1/17 |

| Ricciardi E 2012 [54] | 14 | 32 M | N/A | Oral | MA 80–160 mg, MPA 500–1000 mg | 11/14 | N/A | 4/11 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Ushijima K 2023 [7] | 159 | 35 (19–44) MD | 24.5 (15.2–50.8) m | Oral | MPA 400–600 mg | 112/137 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 35 (19–44) MD | 24.5 (15.2–50.8) m | Oral + Met | MPA 400–600 mg, Met 750–2500 mg | 21/22 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Wheeler D 2007 [55] | 11 | 35.3 M | N/A | Oral | N/A | 4/9 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1/9 | 4/9 |

| 35.3 M | N/A | IUD | LNG | 2/2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0/2 | 0/2 | ||

| Yamagami W 2018 [56] | 65 | 36 (20–45) MD | 21.3 (16.4–40.2) m | Oral | MPA 400–600 mg | 64/65 | 27/64 | 19/65 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Zhang X 2023 [57] | 20 | 33.4 ± 1.1 M | 24.0 ± 1.2 M | Oral | MPA 500 mg | 16/20 | 1/16 | N/A | N/A | 2/20 | 2/20 |

| Minaguchi T 2007 [58] | 12 | 37.7 M | N/A | Oral | MPA 400–600 mg | 11/12 | 4/11 | 5/9 | 2/9 | N/A | N/A |

| Shan W 2014 [59] | 16 | 34 ± 7.1 M | N/A | Oral | MA 160 mg | 2/8 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2/8 | 4/8 |

| 36.4 ± 4.2 M | N/A | Oral + Met | MA 160 mg, Met 1500 mg | 6/8 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0/8 | 2/8 | ||

| Signorelli M 2009 [60] | 10 | N/A | N/A | Oral | Natural progesterone 200 mg | 1/10 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 4/10 |

| Kim MK 2016 [61] | 15 | 42.67 M | N/A | IUD | LNG | 15/15 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sebok, P.; Keszthelyi, M.; Vida, B.; Lőczi, L.; Sebők, B.; Merkely, P.; Ács, N.; Keszthelyi, A.; Várbíró, S.; Lintner, B.; et al. Oncologic and Reproductive Outcomes After Fertility-Sparing Treatments for Endometrial Hyperplasia with Atypia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2025, 17, 3966. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243966

Sebok P, Keszthelyi M, Vida B, Lőczi L, Sebők B, Merkely P, Ács N, Keszthelyi A, Várbíró S, Lintner B, et al. Oncologic and Reproductive Outcomes After Fertility-Sparing Treatments for Endometrial Hyperplasia with Atypia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):3966. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243966

Chicago/Turabian StyleSebok, Pál, Márton Keszthelyi, Balázs Vida, Lotti Lőczi, Barbara Sebők, Petra Merkely, Nándor Ács, Attila Keszthelyi, Szabolcs Várbíró, Balázs Lintner, and et al. 2025. "Oncologic and Reproductive Outcomes After Fertility-Sparing Treatments for Endometrial Hyperplasia with Atypia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Cancers 17, no. 24: 3966. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243966

APA StyleSebok, P., Keszthelyi, M., Vida, B., Lőczi, L., Sebők, B., Merkely, P., Ács, N., Keszthelyi, A., Várbíró, S., Lintner, B., & Tóth, R. (2025). Oncologic and Reproductive Outcomes After Fertility-Sparing Treatments for Endometrial Hyperplasia with Atypia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers, 17(24), 3966. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243966