Oncolytic Viruses in Glioblastoma: Clinical Progress, Mechanistic Insights, and Future Therapeutic Directions

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Virus Platforms and Strategies

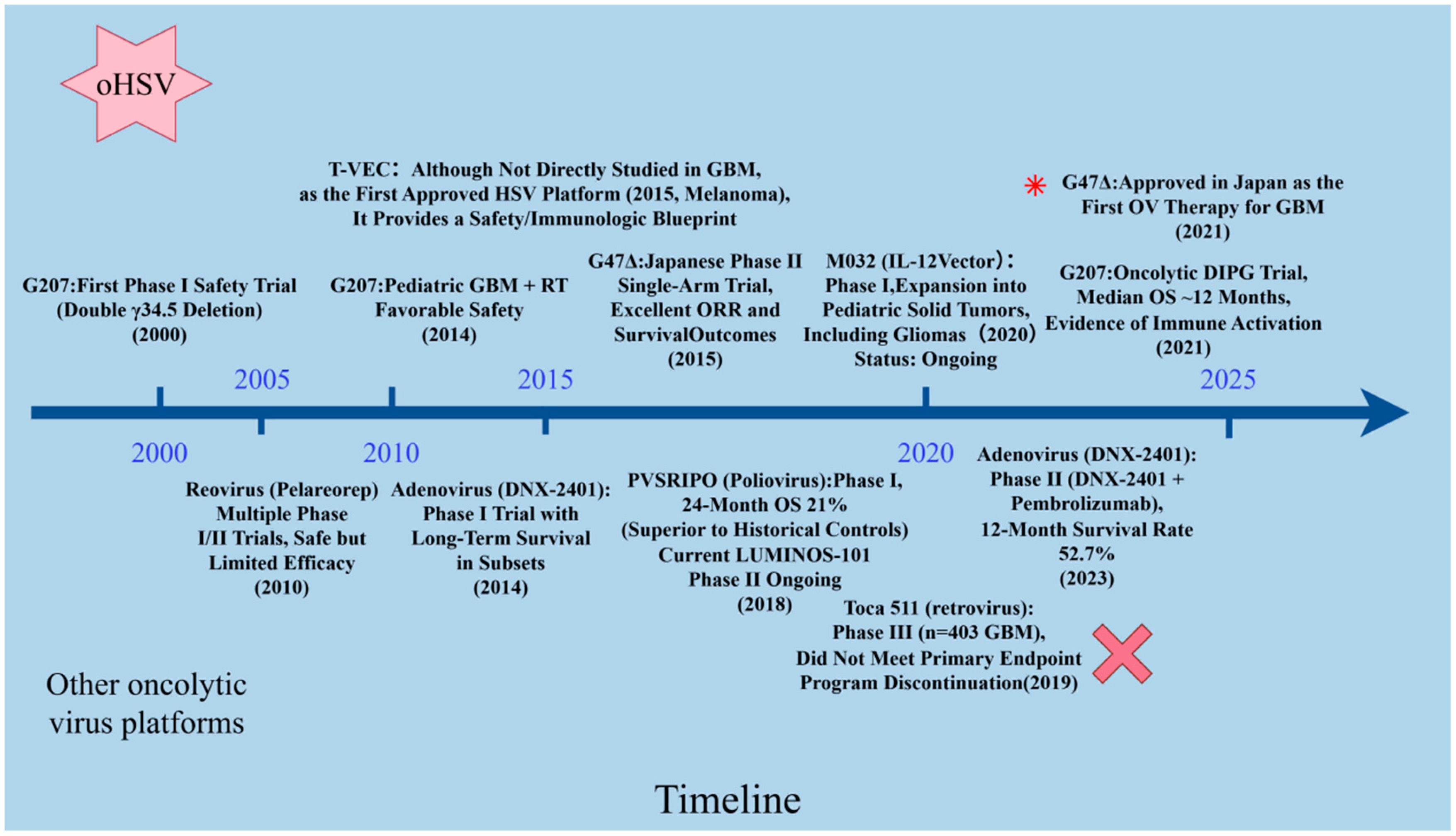

2.1. Oncolytic Herpes Simplex Virus (oHSV)

2.2. Adenovirus

2.3. Reovirus

2.4. Newcastle Disease Virus (NDV)

2.5. Vaccinia Virus

2.6. Other Vectors

3. Completed and Ongoing Clinical Studies of Oncolytic Viruses in GBM

3.1. oHSV Clinical Trials

3.2. Adenovirus Clinical Trials

3.3. Reovirus Clinical Trials

3.4. Newcastle Disease Virus Clinical Trials

3.5. Clinical Trials of Other Vectors

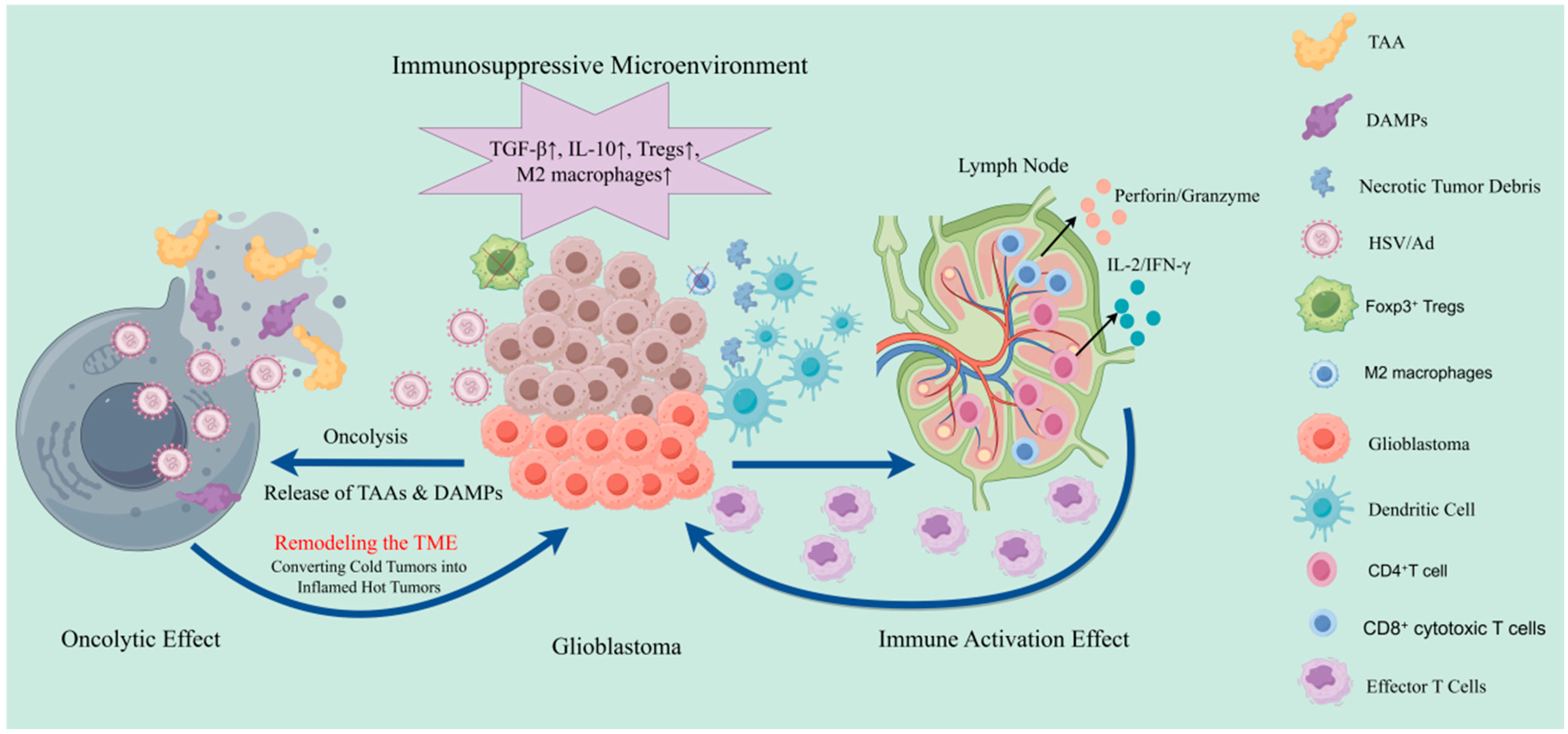

4. Preclinical Study on Mechanisms and Rational Combination Strategies of Oncolytic Virus Platforms in Glioblastoma

5. Future Directions

- (1)

- Programmable viral chassis. Rationally engineered “smart” viruses incorporate conditional replication logic, activating only under tumor-specific signals to reduce off-target toxicity. Incorporation of synthetic biology elements (e.g., genetic logic gates, CRISPR-based targeting) may enhance selectivity. Armed constructs are expanding beyond cytokines to encode checkpoint inhibitors, stromal remodelers, or bispecific antibodies. Recent work demonstrates that oHSV encoding anti-CD47 IgG1 functions as a sustained intratumoral antibody factory, potentiating innate and adaptive antitumor immunity [1].

- (2)

- Innovative delivery strategies. To bypass the BBB and enhance biodistribution, approaches include nanoparticle or liposome encapsulation, as well as cellular carriers such as mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) with tumor-homing properties [28,35]. MSC-based “Trojan horse” vectors may improve systemic delivery. Novel routes—such as intranasal administration or focused ultrasound-mediated BBB disruption—are also under development.

- (3)

- Rational combinations. Evidence suggests OV synergy with immune checkpoint inhibitors, CAR-T cells, radiotherapy, or targeted therapies. For example, DNX-2401 combined with PD-1 blockade has yielded notable survival benefit [23]. OV-mediated antigen release may further enhance CAR-T efficacy, motivating clinical exploration of OV–CAR-T co-therapy [36]. Optimizing sequencing, dosing, and combinatorial regimens will be critical to maximize synergy and overcome GBM’s immune resistance, exemplified by oncolytic adenoviruses encoding bispecific T cell engagers to modulate the tumor microenvironment [37].

- (4)

- Biomarker-driven personalization. Future studies will emphasize biomarker-guided patient stratification. Genomic signatures (e.g., tumor mutational burden, interferon response), receptor expression, and immunohistochemical markers may inform responsiveness to OVs. Circulating biomarkers such as ctDNA or cytokine panels may provide real-time readouts of therapeutic efficacy and prognosis [28].

- (5)

- Expanded indications and regulatory momentum. With recent regulatory milestones (e.g., G47Δ approval in Japan), global development and trial registration of OVs are accelerating. New platforms beyond HSV are under exploration, while lessons from failed programs (e.g., Toca 511 phase III [18]) underscore the need for optimized design and robust trial methodology. Phase III validation remains essential to secure widespread adoption.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, B.; Tian, L.; Chen, J.; Wang, J.; Ma, R.; Dong, W.; Li, A.; Zhang, J.; Antonio Chiocca, E.; Kaur, B.; et al. An oncolytic virus expressing a full-length antibody enhances antitumor innate immune response to glioblastoma. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Hedberg, J.; Montagano, J.; Seals, M.; Puri, S. Oncolytic Virus Therapies in Malignant Gliomas: Advances and Clinical Trials. Cancers 2025, 17, 3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todo, T.; Ino, Y.; Ohtsu, H.; Shibahara, J.; Tanaka, M. A phase I/II study of triple-mutated oncolytic herpes virus G47∆ in patients with progressive glioblastoma. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suryawanshi, Y.R.; Schulze, A.J. Oncolytic Viruses for Malignant Glioma: On the Verge of Success? Viruses 2021, 13, 1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, R.-B.; Yap, Y.H.-Y. Talimogene Laherparepvec (T-VEC): Expanding Horizons in Oncolytic Viral: Therapy Across Multiple Cancer Types. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2025, 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, S.; Makvandi, M.; Abbasi, S.; Azadmanesh, K.; Teimoori, A. Developing oncolytic Herpes simplex virus type 1 through UL39 knockout by CRISPR-Cas9. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2020, 23, 937. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, K.; Meisen, W.H.; Mitchell, P.; Estrada, J.; Zhan, J.; Orf, J.; Li, P.; de Zafra, C.; Qing, J.; DeVoss, J. Oncolytic virus HSV-1/ICP34. 5-/ICP47-/mFLT3L/mIL12 promotes systemic anti-tumor responses and cooperates with immuno-modulatory agents in multiple mouse syngeneic tumor models. Cancer Res. 2021, 81 (Suppl. S13), S1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, K.; Nibbs, R.J.; Fraser, A.R. Going viral: Targeting glioblastoma using oncolytic viruses. Immunother. Adv. 2025, 5, ltaf024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Nava, D.; Ausejo-Mauleon, I.; Laspidea, V.; Gonzalez-Huarriz, M.; Lacalle, A.; Casares, N.; Zalacain, M.; Marrodan, L.; García-Moure, M.; Ochoa, M.C. The oncolytic adenovirus Delta-24-RGD in combination with ONC201 induces a potent antitumor response in pediatric high-grade and diffuse midline glioma models. Neuro-Oncology 2024, 26, 1509–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meulen-Muileman, I.H.; Amado-Azevedo, J.; Lamfers, M.L.; Kleijn, A.; Idema, S.; Noske, D.P.; Dirven, C.M.; van Beusechem, V.W. Adenovirus-Neutralizing and Infection-Promoting Activities Measured in Serum of Human Brain Cancer Patients Treated with Oncolytic Adenovirus Ad5-∆ 24. RGD. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Wang, X.; Jin, L.; Luo, H.; Yang, Z.; Yang, N.; Lin, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, X.; He, Z. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell exosomes deliver potent oncolytic reovirus to acute myeloid leukemia cells. Virology 2024, 598, 110171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginting, T.E.; Christian, S.; Larasati, Y.O.; Suryatenggara, J.; Suriapranata, I.M.; Mathew, G. Antiviral interferons induced by Newcastle disease virus (NDV) drive a tumor-selective apoptosis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuoco, J.A.; Rogers, C.M.; Mittal, S. The oncolytic Newcastle disease virus as an effective immunotherapeutic strategy against glioblastoma. Neurosurg. Focus 2021, 50, E8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousar, K.; Naseer, F.; Abduh, M.S.; Anjum, S.; Ahmad, T. CD44 targeted delivery of oncolytic Newcastle disease virus encapsulated in thiolated chitosan for sustained release in cervical cancer: A targeted immunotherapy approach. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1175535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, N.; Jeon, Y.-H.; Yoo, J.; Shin, S.-k.; Lee, S.; Park, M.-J.; Jung, B.-J.; Hong, Y.-K.; Lee, D.-S.; Oh, K. Generation of novel oncolytic vaccinia virus with improved intravenous efficacy through protection against complement-mediated lysis and evasion of neutralization by vaccinia virus-specific antibodies. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e006024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lu, J.; Guo, G.; Yu, J. Immunotherapy for recurrent glioblastoma: Practical insights and challenging prospects. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, S.C.; Szczeponik, M.G.; Dessila, J.; Dittus, K.; Engeland, C.E.; Jäger, D.; Ungerechts, G.; Leber, M.F. Oncolytic measles virus encoding microRNA for targeted RNA interference. Viruses 2023, 15, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloughesy, T.F.; Petrecca, K.; Walbert, T.; Butowski, N.; Salacz, M.; Perry, J.; Damek, D.; Bota, D.; Bettegowda, C.; Zhu, J.J.; et al. Effect of Vocimagene Amiretrorepvec in Combination with Flucytosine vs Standard of Care on Survival Following Tumor Resection in Patients with Recurrent High-Grade Glioma: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 1939–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, G.K.; Bernstock, J.D.; Chen, D.; Nan, L.; Moore, B.P.; Kelly, V.M.; Youngblood, S.L.; Langford, C.P.; Han, X.; Ring, E.K.; et al. Enhanced Sensitivity of Patient-Derived Pediatric High-Grade Brain Tumor Xenografts to Oncolytic HSV-1 Virotherapy Correlates with Nectin-1 Expression. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, G.K.; Johnston, J.M.; Bag, A.K.; Bernstock, J.D.; Li, R.; Aban, I.; Kachurak, K.; Nan, L.; Kang, K.D.; Totsch, S.; et al. Oncolytic HSV-1 G207 Immunovirotherapy for Pediatric High-Grade Gliomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1613–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, A.L.; Solomon, I.H.; Landivar, A.M.; Nakashima, H.; Woods, J.K.; Santos, A.; Masud, N.; Fell, G.; Mo, X.; Yilmaz, A.S.; et al. Clinical trial links oncolytic immunoactivation to survival in glioblastoma. Nature 2023, 623, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, F.F.; Conrad, C.; Gomez-Manzano, C.; Yung, W.K.A.; Sawaya, R.; Weinberg, J.S.; Prabhu, S.S.; Rao, G.; Fuller, G.N.; Aldape, K.D.; et al. Phase I Study of DNX-2401 (Delta-24-RGD) Oncolytic Adenovirus: Replication and Immunotherapeutic Effects in Recurrent Malignant Glioma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1419–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassiri, F.; Patil, V.; Yefet, L.S.; Singh, O.; Liu, J.; Dang, R.M.A.; Yamaguchi, T.N.; Daras, M.; Cloughesy, T.F.; Colman, H.; et al. Oncolytic DNX-2401 virotherapy plus pembrolizumab in recurrent glioblastoma: A phase 1/2 trial. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 1370–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desjardins, A.; Gromeier, M.; Herndon, J.E., 2nd; Beaubier, N.; Bolognesi, D.P.; Friedman, A.H.; Friedman, H.S.; McSherry, F.; Muscat, A.M.; Nair, S.; et al. Recurrent Glioblastoma Treated with Recombinant Poliovirus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendall, J.; Chalmers, A.; McBain, C.; Melcher, A.; Samson, A.; Phillip, R.; Brown, S.; Short, S. Ctim-14. Pelareorep and Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor (Gm-Csf) with Standard Chemoradiotherapy/Adjuvant Temozolomide for Glioblastoma Multiforme (Gbm) Patients: Reoglio Phase I Trial Results. Neuro-Oncology 2020, 22 (Suppl. S2), ii35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, J.M.; Mustafa, Z.; Ideris, A. Newcastle disease virus interaction in targeted therapy against proliferation and invasion pathways of glioblastoma multiforme. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 386470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, E.; Dooley, K.E.; Keith Anderson, S.; Kurokawa, C.B.; Carrero, X.W.; Uhm, J.H.; Federspiel, M.J.; Leontovich, A.A.; Aderca, I.; Viker, K.B.; et al. Carcinoembryonic antigen-expressing oncolytic measles virus derivative in recurrent glioblastoma: A phase 1 trial. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomari, O.; Eyvazova, H.; Güney, B.; Al Juhmani, R.; Odabasi, H.; Al-Rawabdeh, L.; Mokresh, M.E.; Erginoglu, U.; Keles, A.; Baskaya, M.K. Oncolytic Therapies for Glioblastoma: Advances, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Cancers 2025, 17, 2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todo, T.; Ito, H.; Ino, Y.; Ohtsu, H.; Ota, Y.; Shibahara, J.; Tanaka, M. Intratumoral oncolytic herpes virus G47∆ for residual or recurrent glioblastoma: A phase 2 trial. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1630–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, S.; Arai, Y.; Tasaki, M.; Yamashita, M.; Murakami, R.; Kawase, T.; Amino, N.; Nakatake, M.; Kurosaki, H.; Mori, M. Intratumoral expression of IL-7 and IL-12 using an oncolytic virus increases systemic sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eaax7992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonoda-Fukuda, E.; Takeuchi, Y.; Ogawa, N.; Noguchi, S.; Takarada, T.; Kasahara, N.; Kubo, S. Targeted Suicide Gene Therapy with Retroviral Replicating Vectors for Experimental Canine Cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddox, J.F.; Amuzie, C.J.; Li, M.; Newport, S.W.; Sparkenbaugh, E.; Cuff, C.F.; Pestka, J.J.; Cantor, G.H.; Roth, R.A.; Ganey, P.E. Bacterial-and viral-induced inflammation increases sensitivity to acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A 2009, 73, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, K.; Connor, K.; Meylan, M.; Bougoüin, A.; Salvucci, M.; Bielle, F.; O’farrell, A.; Sweeney, K.; Weng, L.; Bergers, G. Identification, validation and biological characterisation of novel glioblastoma tumour microenvironment subtypes: Implications for precision immunotherapy. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kardani, K.; Sanchez Gil, J.; Rabkin, S.D. Oncolytic herpes simplex viruses for the treatment of glioma and targeting glioblastoma stem-like cells. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1206111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zawit, M.; Swami, U.; Awada, H.; Arnouk, J.; Milhem, M.; Zakharia, Y. Current status of intralesional agents in treatment of malignant melanoma. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalise, L.; Kato, A.; Ohno, M.; Maeda, S.; Yamamichi, A.; Kuramitsu, S.; Shiina, S.; Takahashi, H.; Ozone, S.; Yamaguchi, J.; et al. Efficacy of cancer-specific anti-podoplanin CAR-T cells and oncolytic herpes virus G47Δ combination therapy against glioblastoma. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2022, 26, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.J.; So, E.Y.; Akosman, B.; Lee, Y.E.; Raufi, A.G.; Bertone, P.; Reginato, A.M.; Chen, C.C.; Lawler, S.E.; Wong, E.T.; et al. Enabling CAR-T Cell Immunotherapy in Glioblastoma by Modifying Tumor Microenvironment via Oncolytic Adenovirus Encoding Bispecific T Cell Engager. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Platform (Family; Genome) | Cargo Capacity | Key Modifications |

|---|---|---|

| HSV-1 (oHSV; dsDNA) | Large (>30 kb) | γ34.5 and ICP6 deletions; ICP47 deletion |

| Adenovirus (CRAd; dsDNA) | Moderate (~7.5 kb) | Δ24 E1A deletion; RGD-modified fibers |

| Reovirus (dsRNA) | Minimal | Native RAS-selective tropism |

| NDV (−ssRNA) | Minimal | Fusogenic strains |

| Vaccinia virus (dsDNA) | Very large (>25 kb) | Large genome enabling engineering |

| PVSRIPO (+ssRNA) | Minimal | Rhinovirus IRES replacement; CD155 targeting |

| Measles virus (−ssRNA) | Minimal | Edmonston lineage |

| Platform/Agent | Trial (Phase; N) and Identifier | Setting/Line | Delivery and Dosing | Primary Endpoints | Efficacy Summary | Safety Summary | Notes/Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| oHSV (teserpaturev, G47Δ) | Single-arm Phase II; n = 19 | Residual or recurrent adult GBM | Stereotactic intratumoral; ≤6 injections | 1-yr OS | 1-yr OS 84.2%; median OS 20.2 mo; disease control 95% | Mostly grade 1–2 pyrexia, vomiting, leukopenia; manageable | Approved in Japan (2021). Pivotal data in Nature Medicine with identical figures [18] |

| oHSV (G207, adults ± RT) | Phase I; n ≈ 9 | Recurrent adult GBM | Intratumoral infusion + single 5 Gy RT boost | Safety, feasibility | Radiographic responses; biological activity observed | No encephalitis; acceptable AE profile | Early “virus + focal RT” experience in adults [19] |

| oHSV (G207, pediatrics) | Phase I; n = 12 (11 evaluable) | Recurrent/progressive pediatric HGG | Intratumoral via catheter; ±5 Gy RT | Safety; biological activity | Median OS 12.2 mo (95% CI 8.0–16.4); 4/11 alive ≥ 18 mo; ↑ TILs | No DLTs; tolerable | NEJM study demonstrating immunologic conversion in pediatric HGG [20] |

| oHSV (CAN-3110; nestin-controlled ICP34.5) | Phase I; n = 41 | Recurrent HGG/rGBM | Single stereotactic intratumoral injection; 106–1010 PFU | Safety; translational immunology | HSV-1 seropositivity linked to prolonged OS; TCR diversification post-dose | No DLTs; well tolerated | Nature (2023) mechanistic correlative trial; ongoing expansion/fast-track [21] |

| oHSV (M032; IL-12-expressing) | Phase I (ongoing) | Adult HGG | Intratumoral IL-12-armed oHSV | Safety (DLTs); RP2D | Early reports: acceptable safety; results pending | No DLTs to date (interim) | Registered design and early safety reporting. (NCT02062827) |

| Adenovirus (DNX-2401) | Phase I; n = 37 (two cohorts) | Recurrent HGG/GBM | Single intratumoral injection (±resection + reinjection) | Safety; ORR | 20% survived >3 yrs after single injection | Favorable profile | Landmark JCO study establishing durable benefit in a subset [22] |

| DNX-2401 + Pembrolizumab | Multicenter Phase II (KEYNOTE-192); n = 49 | Recurrent GBM | Intratumoral DNX-2401 → IV pembrolizumab (q3w) | ORR; OS-12 | ORR 10.4%; OS-12 52.7%; median OS 12.5 mo; responders lived >3 yrs | Well tolerated; no DLTs | Nature Medicine 2023; prototypical OV + PD-1 synergy signal [23] |

| PVSRIPO (modified poliovirus) | Phase I; n = 61 (NCT01491893) | Recurrent GBM | Convection-enhanced infusion (CED) | MTD/RP2D; OS | OS plateau 21% at 24–36 mo | 19% grade ≥ 3 AEs; one hemorrhage at high dose | NEJM 2018 with long-tail survival plateau [24] |

| Reovirus (pelareorep) | Phase Ib (ReoGlio); n = 15 | Newly diagnosed GBM (with CRT + TMZ) | GM-CSF (d1–3); IV pelareorep (wks 1 and 4) + CRT + TMZ | Feasibility; PFS (exploratory) | mPFS ≈ 8 mo; dose–response trend | Well tolerated with CRT/TMZ | Peer-reviewed feasibility + sponsor releases; larger trials needed [25] |

| NDV (NDV-HUJ) | Early Phase I/II; n ≈ 11–14 | Recurrent GBM/HGG | Repeated IV dosing | Safety; signals of activity | Case responses reported; limited efficacy | Acceptable | Foundational IV NDV experience; human data remain sparse [26] |

| Measles virus (MV-CEA) | Phase I; n = 22 | Recurrent GBM | Intracavitary alone vs. intra + cavity dosing | Safety (MTD); OS (exploratory) | mOS 11.6 mo; 1-yr OS 45.5% | No DLTs; predictable AESIs | Nature Communications 2024; modern design with surgical cavity dosing [27] |

| OV Platform | oHSV (G47Δ, CAN-3110, M032, G207) | Adenovirus (DNX-2401) | PVSRIPO (Poliovirus Chimera) | Reovirus (Pelareorep) | NDV (HUJ, Fusogenic Strains) | Vaccinia Virus (Armed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core engineering/payloads | γ34.5/ICP6 deletion; ±ICP47 deletion; payloads: GM-CSF, IL-12, antibodies (e.g., anti-CD47) | Δ24 E1A deletion; RGD-modified fibers; payloads: IL-12, CD40L | Rhinovirus IRES replacement; CD155 targeting | Native oncotropism; IV dosing ± GM-CSF | Attenuated/lentogenic strains; fusogenic variants | Large cargo; GM-CSF, IL-2/12/21; bispecifics |

| Main mechanisms in GBM | Potent oncolysis; DAMP/TAA release; ↑ MHC-I; TME “heating” (↑ CD8, ↓ Treg/MDSC) | Oncolysis; immunogenic cell death; DC priming | Type-I IFN induction; immune reset; bystander killing | Systemic innate activation; RAS-selective replication | Fusogenic oncolysis; type-I IFN activation | Rapid lysis; strong antigen presentation; vascular remodeling |

| Rational combinations | Anti-PD-1 after priming; peri-OV low-dose RT; OV → CAR-T; ±anti-VEGF | DNX-2401 → anti-PD-1; RT synergy; ±CD40 agonism; TMZ (MGMT-methylated) | PVSRIPO → anti-PD-1 (delayed); RT; STING/TLR agonists | Reovirus → anti-PD-1; CRT/TMZ backbone; ±GM-CSF | NDV → anti-PD-1; RT synergy; ±TLR3 agonists | Vaccinia → anti-PD-1; RT; bispecific-armed vectors |

| Key limitations/safety | Cerebral edema, PSP; seizure risk; herpetic lesions—acyclovir control | Flu-like AEs; edema; limited parenchymal spread | Procedure-related hemorrhage; neutralizing antibodies | Generally safe; neutralized by pre-existing antibodies; BBB limits | Systemic reactogenicity; neutralization; sparse clinical data | Reactogenicity; neurotropism risk; managed with antivirals |

| Priority translational readouts | CD8/Treg ratio; PD-L1 induction; TCR clonality expansion; spatial IHC/IMC of DC/TAM; IFN-γ/CXCL9/10; single-cell/Visium signatures; rCBV/rCBF and iRANO concordance | OS-12 vs. historical; intratumoral Ad DNA kinetics; DC activation (CD86), CXCL10; TCR expansion; MRI texture/volumetrics [9] | Long-tail OS plateau; ISG surge; myeloid activation signatures; CSF cytokines; catheter tract coverage maps [35] | Blood viral RNA/DNA; IFN-α/β, IL-6 trajectories; peripheral NK activation; mPFS with CRT [32] | IFN gene signatures; chemokine induction; changes in myeloid subsets [12] | Cytokine panels; endothelial/VECAM changes; intratumoral payload expression; imaging theranostics (if NIS payload) [30] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Su, S.; Cheng, G.; Zhao, H.; Sun, J.; Sun, G.; Li, F.; Hui, R.; Liu, M.; et al. Oncolytic Viruses in Glioblastoma: Clinical Progress, Mechanistic Insights, and Future Therapeutic Directions. Cancers 2025, 17, 3948. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243948

Liu J, Wang Y, Su S, Cheng G, Zhao H, Sun J, Sun G, Li F, Hui R, Liu M, et al. Oncolytic Viruses in Glioblastoma: Clinical Progress, Mechanistic Insights, and Future Therapeutic Directions. Cancers. 2025; 17(24):3948. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243948

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jiayu, Yuxin Wang, Shichao Su, Gang Cheng, Hulin Zhao, Junzhao Sun, Guochen Sun, Fangye Li, Rui Hui, Meijing Liu, and et al. 2025. "Oncolytic Viruses in Glioblastoma: Clinical Progress, Mechanistic Insights, and Future Therapeutic Directions" Cancers 17, no. 24: 3948. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243948

APA StyleLiu, J., Wang, Y., Su, S., Cheng, G., Zhao, H., Sun, J., Sun, G., Li, F., Hui, R., Liu, M., Wu, L., Wu, D., Yang, F., Dang, Y., Hei, J., Li, Y., Gao, Z., Wang, B., Bai, Y., ... Zhang, J. (2025). Oncolytic Viruses in Glioblastoma: Clinical Progress, Mechanistic Insights, and Future Therapeutic Directions. Cancers, 17(24), 3948. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17243948