Neutrophil Dynamics Contribute to Disease Progression and Poor Survival in Pancreatic Cancer

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Human Tumor Specimens and Animal Models

2.2. Immunostaining and Quantitation

2.3. Gene Expression Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Increased Neutrophil Infiltration and NETs with Disease Progression

3.2. CXCR2 and Its Ligands Play an Important Role in Neutrophil Recruitment

3.3. Chemotherapy Enhances Neutrophil Recruitment and NET Formation in Patient Samples

3.4. Altered Neutrophil Phenotype in PC with Disease Progression

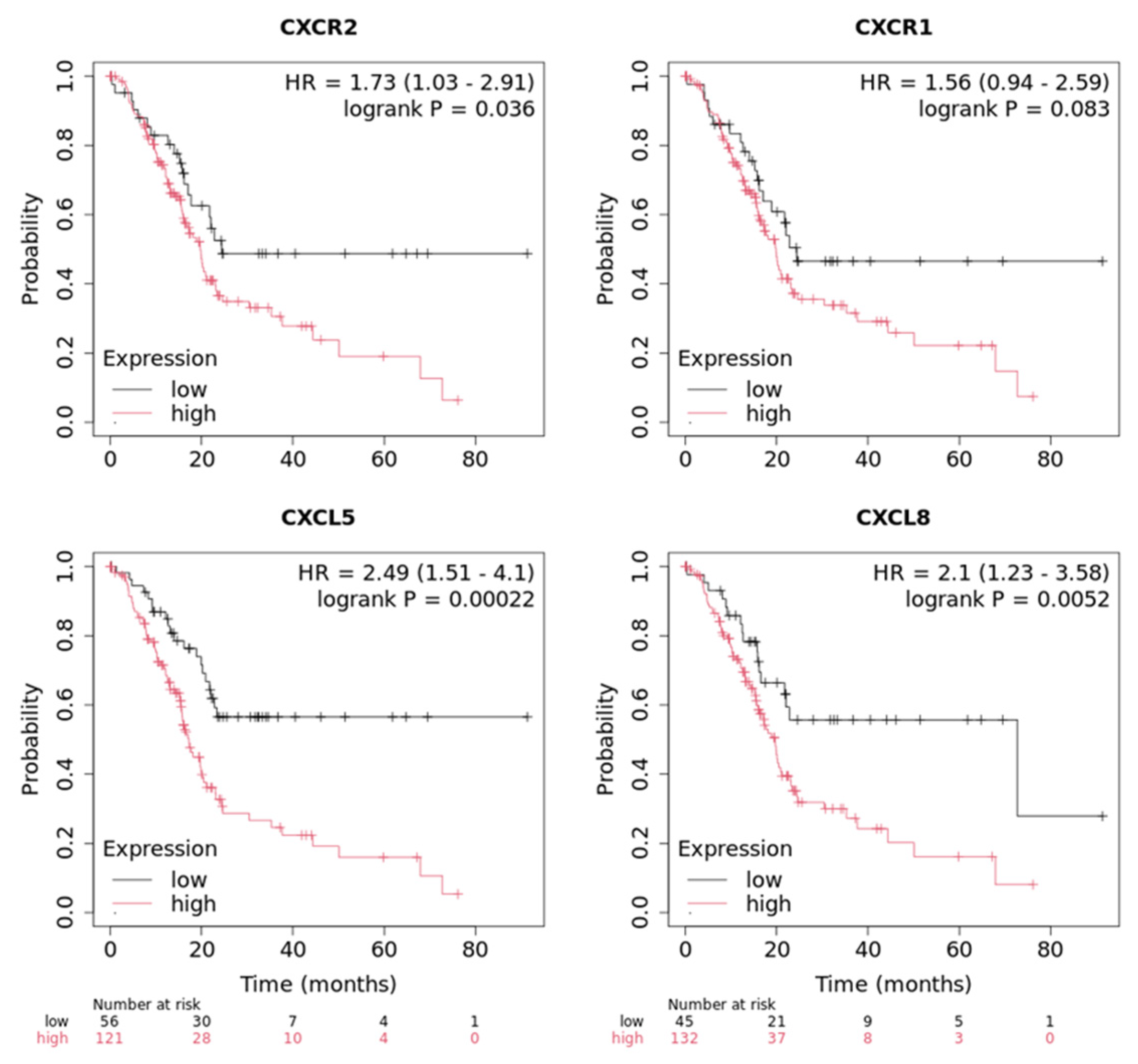

3.5. Expression of CXCR1/2 and Its Ligands Is Associated with Poor Survival

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamska, A.; Elaskalani, O.; Emmanouilidi, A.; Kim, M.; Razak, N.B.A.; Metharom, P.; Falasca, M. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2018, 68, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, A.S.; Wu, X.; Zhuang, G.; Ngu, H.; Kasman, I.; Zhang, J.; Vernes, J.-M.; Jiang, Z.; Meng, Y.G.; Peale, F.V.; et al. An interleukin-17–mediated paracrine network promotes tumor resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1114–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaskalani, O.; Razak, N.B.A.; Falasca, M.; Metharom, P. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition as a therapeutic target for overcoming chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2017, 9, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, B.; Lee, S.; Youn, H.; Kim, E.; Kim, W.; Youn, B. The role of tumor microenvironment in therapeutic resistance. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 3933–3945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakacs, G.; Paterson, J.K.; Ludwig, J.A.; Booth-Genthe, C.; Gottesman, M.M. Targeting multidrug resistance in cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006, 5, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Ahmad, A.; Banerjee, S.; Azmi, A.S.; Kong, D.; Sarkar, F.H. Pancreatic cancer: Understanding and overcoming chemoresistance. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 8, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Qin, J.; Zhao, J.; Li, J.; Li, D.; Popp, M.; Popp, F.; Alakus, H.; Kong, B.; Dong, Q.; et al. Inflammatory IFIT3 renders chemotherapy resistance by regulating post-translational modification of VDAC2 in pancreatic cancer. Theranostics 2020, 10, 7178–7192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, S.; Pöttler, M.; Lan, B.; Grützmann, R.; Pilarsky, C.; Yang, H. Chemoresistance in Pancreatic Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Carstens, J.L.; Kim, J.; Scheible, M.; Kaye, J.; Sugimoto, H.; Wu, C.-C.; LeBleu, V.S.; Kalluri, R. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is dispensable for metastasis but induces chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. Nature 2015, 527, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarantis, P.; Koustas, E.; Papadimitropoulou, A.; Papavassiliou, A.G.; Karamouzis, M.V. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Treatment hurdles, tumor microenvironment and immunotherapy. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2020, 12, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colotta, F.; Allavena, P.; Sica, A.; Garlanda, C.; Mantovani, A. Cancer-related inflammation, the seventh hallmark of cancer: Links to genetic instability. Carcinogenesis 2009, 30, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, B.; Spicer, J.; Giannais, B.; Fallavollita, L.; Brodt, P.; Ferri, L.E. Systemic inflammation increases cancer cell adhesion to hepatic sinusoids by neutrophil mediated mechanisms. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 125, 1298–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padoan, A.; Plebani, M.; Basso, D. Inflammation and Pancreatic Cancer: Focus on Metabolism, Cytokines, and Immunity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wu, L.; Yan, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, M.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y. Inflammation and tumor progression: Signaling pathways and targeted intervention. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faurschou, M.; Borregaard, N. Neutrophil granules and secretory vesicles in inflammation. Microbes Infect. 2003, 5, 1317–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.L.; Lim, C.H.; Tay, F.W.; Goh, C.C.; Devi, S.; Malleret, B.; Lee, B.; Bakocevic, N.; Chong, S.Z.; Evrard, M.; et al. Neutrophils Self-Regulate Immune Complex-Mediated Cutaneous Inflammation through CXCL2. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2016, 136, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, A.J.; Falkowski, N.R.; McDonald, R.A.; Pandit, C.R.; Young, V.B.; Huffnagle, G.B. Interleukin-23 (IL-23), independent of IL-17 and IL-22, drives neutrophil recruitment and innate inflammation during Clostridium difficile colitis in mice. Immunology 2016, 147, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosales, C. Neutrophil: A Cell with Many Roles in Inflammation or Several Cell Types? Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Xia, Y.; Su, J.; Quan, F.; Zhou, H.; Li, Q.; Feng, Q.; Lin, C.; Wang, D.; Jiang, Z. Neutrophil diversity and function in health and disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Figueroa, E.; Álvarez-Carrasco, P.; Ortega, E.; Maldonado-Bernal, C. Neutrophils: Many Ways to Die. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 631821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burn, G.L.; Foti, A.; Marsman, G.; Patel, D.F.; Zychlinsky, A. The Neutrophil. Immunity 2021, 54, 1377–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, B. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 1982, 517–528. [Google Scholar]

- Garley, M.; Jablonska, E.; Dabrowska, D. NETs in cancer. Tumour Biol. 2016, 37, 14355–14361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Tang, W.; Liu, T.; Xu, P.; Zhu, D.; Ji, M.; Huang, W.; Ren, L.; Wei, Y.; Xu, J. Cell-free DNA derived from cancer cells facilitates tumor malignancy through Toll-like receptor 9 signaling-triggered interleukin-8 secretion in colorectal cancer. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2018, 50, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teijeira, Á.; Garasa, S.; Gato, M.; Alfaro, C.; Migueliz, I.; Cirella, A.; de Andrea, C.; Ochoa, M.C.; Otano, I.; Etxeberria, I.; et al. CXCR1 and CXCR2 Chemokine Receptor Agonists Produced by Tumors Induce Neutrophil Extracellular Traps that Interfere with Immune Cytotoxicity. Immunity 2020, 52, 856–871.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, P.C.; Topham, J.T.; Awrey, S.; Tavakoli, H.; Carroll, R.; Brown, W.S.; Gerbec, Z.J.; Kalloger, S.E.; Karasinska, J.M.; Tang, P.; et al. Neutrophil extracellular trap gene expression signatures identify prognostic and targetable signaling axes for inhibiting pancreatic tumour metastasis. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsis, M.; Drosou, P.; Tatsis, V.; Markopoulos, G.S. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps and Pancreatic Cancer Development: A Vicious Cycle. Cancers 2022, 14, 3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cools-Lartigue, J.; Spicer, J.; McDonald, B.; Gowing, S.; Chow, S.; Giannias, B.; Bourdeau, F.; Kubes, P.; Ferri, L. Neutrophil extracellular traps sequester circulating tumor cells and promote metastasis. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 3446–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demkow, U. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) in Cancer Invasion, Evasion and Metastasis. Cancers 2021, 13, 4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, W.; Yin, H.; Li, H.; Yu, X.; Xu, H.; Liu, L. Neutrophil extracellular DNA traps promote pancreatic cancer cells migration and invasion by activating EGFR/ERK pathway. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 5443–5456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaltenmeier, C.; Simmons, R.L.; Tohme, S.; Yazdani, H.O. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) in Cancer Metastasis. Cancers 2021, 13, 6131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masucci, M.T.; Minopoli, M.; Del Vecchio, S.; Carriero, M.V. The Emerging Role of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) in Tumor Progression and Metastasis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogi, S.; Kagawa, S.; Taniguchi, A.; Yagi, T.; Kanaya, N.; Kakiuchi, Y.; Yasui, K.; Fuji, T.; Kono, Y.; Kikuchi, S.; et al. Gemcitabine-induced neutrophil extracellular traps via interleukin-8-CXCR1/2 pathway promote chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsugi, K.; Kawata, K.; Noritake, H.; Chida, T.; Ohta, K.; Ito, J.; Takatori, S.; Yamashita, M.; Hanaoka, T.; Umemura, M.; et al. Prognostic value of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in patients with advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma treated with systemic chemotherapy. Ann. Med. 2024, 56, 2398725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, A.; Thompson, C.; Hall, B.R.; Jain, M.; Kumar, S.; Batra, S.K. Desmoplasia in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Insight into pathological function and therapeutic potential. Genes Cancer 2018, 9, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, Y.; Xu, D.; Liao, M.-M.; Sun, Y.; Bao, W.-D.; Yao, F.; Ma, L. Barriers and opportunities in pancreatic cancer immunotherapy. npj Precis. Oncol. 2024, 8, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohara, Y.; Valenzuela, P.; Hussain, S.P. The interactive role of inflammatory mediators and metabolic reprogramming in pancreatic cancer. Trends Cancer 2022, 8, 556–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.-J.; Hu, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Xu, L.; Cui, N. Neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR) was associated with prognosis and immunomodulatory in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40, BSR20201190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-H.; Pauklin, S. ROS and TGFβ: From pancreatic tumour growth to metastasis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Qi, H.; Liu, Y.; Duan, C.; Liu, X.; Xia, T.; Chen, D.; Piao, H.-L.; Liu, H.-X. The double-edged roles of ROS in cancer prevention and therapy. Theranostics 2021, 11, 4839–4857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.P.; Rachagani, S.; Souchek, J.J.; Mallya, K.; Johansson, S.L.; Batra, S.K. Novel Pancreatic Cancer Cell Lines Derived from Genetically Engineered Mouse Models of Spontaneous Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma: Applications in Diagnosis and Therapy. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hingorani, S.R.; Petricoin, E.F.; Maitra, A.; Rajapakse, V.; King, C.; Jacobetz, M.A.; Ross, S.; Conrads, T.P.; Veenstra, T.D.; Hitt, B.A.; et al. Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell 2003, 4, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartha, Á.; Győrffy, B. TNMplot.com: A Web Tool for the Comparison of Gene Expression in Normal, Tumor and Metastatic Tissues. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Győrffy, B. Integrated analysis of public datasets for the discovery and validation of survival-associated genes in solid tumors. Innovation 2024, 5, 100625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, S.; Molczyk, C.; Purohit, A.; Ehrhorn, E.; Goel, P.; Prajapati, D.R.; Atri, P.; Kaur, S.; Grandgenett, P.M.; Hollingsworth, M.A.; et al. Differential expression profile of CXC-receptor-2 ligands as potential biomarkers in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2022, 12, 68–90. [Google Scholar]

- Eash, K.J.; Greenbaum, A.M.; Gopalan, P.K.; Link, D.C. CXCR2 and CXCR4 antagonistically regulate neutrophil trafficking from murine bone marrow. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 2423–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Wang, C.; Wang, M.; Liu, M.; Hu, W.; Liang, X.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y. A key regulator of tumor-associated neutrophils: The CXCR2 chemokine receptor. Histochem. J. 2024, 55, 1051–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Guo, R.; Kambara, H.; Ma, F.; Luo, H.R. The role of CXCR2 in acute inflammatory responses and its antagonists as anti-inflammatory therapeutics. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2019, 26, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molczyk, C.; Singh, R.K. CXCR1: A Cancer Stem Cell Marker and Therapeutic Target in Solid Tumors. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, D.R.; Molczyk, C.; Purohit, A.; Saxena, S.; Sturgeon, R.; Dave, B.J.; Kumar, S.; Batra, S.K.; Singh, R.K. Small molecule antagonist of CXCR2 and CXCR1 inhibits tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett. 2023, 563, 216185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namima, D.; Fujihara, S.; Iwama, H.; Fujita, K.; Matsui, T.; Nakahara, M.; Okamura, M.; Hirata, M.; Kono, T.; Fujita, N.; et al. The Effect of Gemcitabine on Cell Cycle Arrest and microRNA Signatures in Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Vivo 2020, 34, 3195–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaji, M.; Saxena, S.; Wu, L.; Prajapati, D.R.; Purohit, A.; Varney, M.L.; Kumar, S.; Rachagani, S.; Ly, Q.P.; Jain, M.; et al. CXCR2 signaling promotes secretory cancer-associated fibroblasts in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 9405–9418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Cheng, X.J.; Moro, A.; Singh, R.K.; Hines, O.J.; Eibl, G. CXCR2-Dependent Endothelial Progenitor Cell Mobilization in Pancreatic Cancer Growth. Transl. Oncol. 2011, 4, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, A.; Saxena, S.; Varney, M.; Prajapati, D.R.; Kozel, J.A.; Lazenby, A.; Singh, R.K. Host Cxcr2-Dependent Regulation of Pancreatic Cancer Growth, Angiogenesis, and Metastasis. Am. J. Pathol. 2021, 191, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purohit, A.; Varney, M.; Rachagani, S.; Ouellette, M.M.; Batra, S.K.; Singh, R.K. CXCR2 signaling regulates KRAS(G12D)-induced autocrine growth of pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 7280–7296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorente, D.; Mateo, J.; Templeton, A.J.; Zafeiriou, Z.; Bianchini, D.; Ferraldeschi, R.; Bahl, A.; Shen, L.; Su, Z.; Sartor, O.; et al. Baseline neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is associated with survival and response to treatment with second-line chemotherapy for advanced prostate cancer independent of baseline steroid use. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 26, 750–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Saxena, S.; Goel, P.; Prajapati, D.R.; Wang, C.; Singh, R.K. Breast Cancer Cell–Neutrophil Interactions Enhance Neutrophil Survival and Pro-Tumorigenic Activities. Cancers 2020, 12, 2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandaker, M.H.; Mitchell, G.; Xu, L.; Andrews, J.D.; Singh, R.; Leung, H.; Madrenas, J.; Ferguson, S.S.; Feldman, R.D.; Kelvin, D.J. Metalloproteinases are involved in lipopolysaccharide- and tumor necrosis factor-alpha-mediated regulation of CXCR1 and CXCR2 chemokine receptor expression. Blood 1999, 93, 2173–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Wu, S.; Varney, M.; Singh, A.P.; Singh, R.K. CXCR1 and CXCR2 silencing modulates CXCL8-dependent endothelial cell proliferation, migration and capillary-like structure formation. Microvasc. Res. 2011, 82, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granados-Principal, S.; Liu, Y.; Guevara, M.L.; Blanco, E.; Choi, D.S.; Qian, W.; Patel, T.; Rodriguez, A.A.; Cusimano, J.; Weiss, H.L.; et al. Inhibition of iNOS as a novel effective targeted therapy against triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2015, 17, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannini, F.; Kashfi, K.; Nath, N. The dual role of iNOS in cancer. Redox Biol. 2015, 6, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, M.M.; Boothby, I.; Clancy, S.; Ahn, R.S.; Liao, W.; Nguyen, D.N.; Schumann, K.; Marson, A.; Mahuron, K.M.; Kingsbury, G.A.; et al. Regulatory T cells use arginase 2 to enhance their metabolic fitness in tissues. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 4, e129756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munder, M. Arginase: An emerging key player in the mammalian immune system. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 158, 638–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vonwirth, V.; Bülbül, Y.; Werner, A.; Echchannaoui, H.; Windschmitt, J.; Habermeier, A.; Ioannidis, S.; Shin, N.; Conradi, R.; Bros, M.; et al. Inhibition of Arginase 1 Liberates Potent T Cell Immunostimulatory Activity of Human Neutrophil Granulocytes. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 617699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishalian, I.; Bayuh, R.; Eruslanov, E.; Michaeli, J.; Levy, L.; Zolotarov, L.; Singhal, S.; Albelda, S.M.; Granot, Z.; Fridlender, Z.G. Neutrophils recruit regulatory T-cells into tumors via secretion of CCL17—A new mechanism of impaired antitumor immunity. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 135, 1178–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bert, S.; Nadkarni, S.; Perretti, M. Neutrophil—T cell crosstalk and the control of the host inflammatory response. Immunol. Rev. 2022, 314, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.L.; Beatty, G.L. Cellular determinants and therapeutic implications of inflammation in pancreatic cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 201, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Pan, B.; Shi, H.; Yi, Y.; Zheng, X.; Ma, H.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, L.; Huang, Y.; et al. Neutrophils’ dual role in cancer: From tumor progression to immunotherapeutic potential. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 140, 112788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Li, C.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Shao, S.; Shao, F.; Wang, H.; Liu, J. Neutrophils in cancer: Dual roles through intercellular interactions. Oncogene 2024, 43, 1163–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Human/Mouse | Primary Antibody | Marker | Source | Catalog No. | Dilution | RRID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Human | Anti-myeloperoxidase | Neutrophils | Thermo Scientific, Fremont, CA, USA | RB-373-A0 | 1:200 | AB_59598 |

| 2 | Human | Cathepsin G | Inflammation | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA | sc-33206 | 1:200 | AB_2087522 |

| 3 | Human | Histone H2A | NETs | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA | Sc-8648 | 1:200 | AB_2118018 |

| 4 | Human | IL8 | CXCL8 | Pierce Endogen, Rockford, IL, USA | M802B | 1:200 | AB_223584 |

| 5 | Human | CXCL5 ELISA capture antibody | CXCL5 | R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA | DY254-05 | 1:500 | AB_2245472 |

| 6 | Mouse | Anti-myeloperoxidase | Neutrophils | Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA | ab9535 | 1:200 | AB_307322 |

| 7 | Mouse | Cathepsin G | Inflammation | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA | Sc-6514 | 1:200 | AB_2087408 |

| 8 | Mouse | Citrullinated Histone H3 | NETs | Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA | Ab5103 | 1:200 | AB_304752 |

| 9 | Mouse | CD3e | T-cells | BD Pharmogen, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA | 553057 | 1:50 | AB_394590 |

| 10 | Mouse | Arginase | Arginase | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA | Sc-271430 | 1:10 | AB_10648473 |

| 11 | Mouse | panNOS | NOS | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA | Sc-58399 | 1:10 | AB_784875 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sturgeon, R.; Goel, P.; Molczyk, C.; Bhola, R.; Grandgenett, P.M.; Hollingsworth, M.A.; Singh, R.K. Neutrophil Dynamics Contribute to Disease Progression and Poor Survival in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 3541. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213541

Sturgeon R, Goel P, Molczyk C, Bhola R, Grandgenett PM, Hollingsworth MA, Singh RK. Neutrophil Dynamics Contribute to Disease Progression and Poor Survival in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancers. 2025; 17(21):3541. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213541

Chicago/Turabian StyleSturgeon, Reegan, Paran Goel, Caitlin Molczyk, Ridhi Bhola, Paul M. Grandgenett, Michael A. Hollingsworth, and Rakesh K. Singh. 2025. "Neutrophil Dynamics Contribute to Disease Progression and Poor Survival in Pancreatic Cancer" Cancers 17, no. 21: 3541. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213541

APA StyleSturgeon, R., Goel, P., Molczyk, C., Bhola, R., Grandgenett, P. M., Hollingsworth, M. A., & Singh, R. K. (2025). Neutrophil Dynamics Contribute to Disease Progression and Poor Survival in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancers, 17(21), 3541. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213541