Tissue Microarray-Based Digital Spatial Profiling of Benign Breast Lobules and Breast Cancers: Feasibility, Biological Coherence, and Cross-Platform Benchmarks

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Cohort and Design

2.2. Construction of Tissue Microarrays (TMAs)

2.3. NanoString Digital Spatial Profiling (DSP)

2.4. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

2.5. Multiplex Immunofluorescence (OPAL)

2.6. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Digital Spatial Profiling (DSP) Quality Control and Reproducibility of DSP Measurements (ICCs)

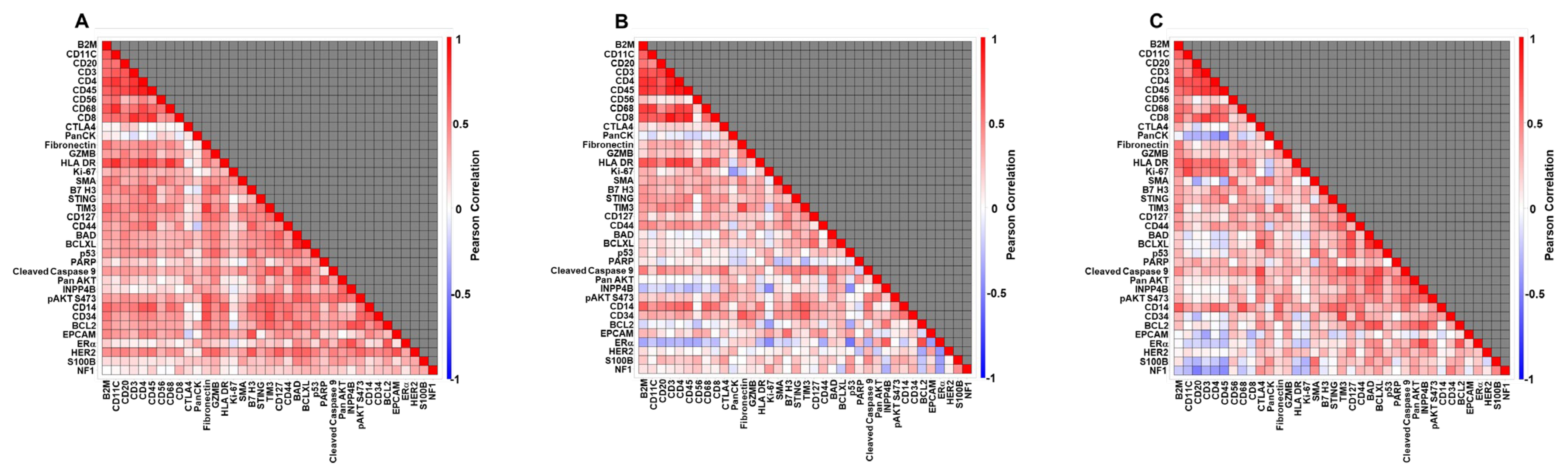

3.3. Biological Coherence: Correlation Among DSP Markers

3.4. Cross-Platform Agreement: DSP Versus IHC and OPAL

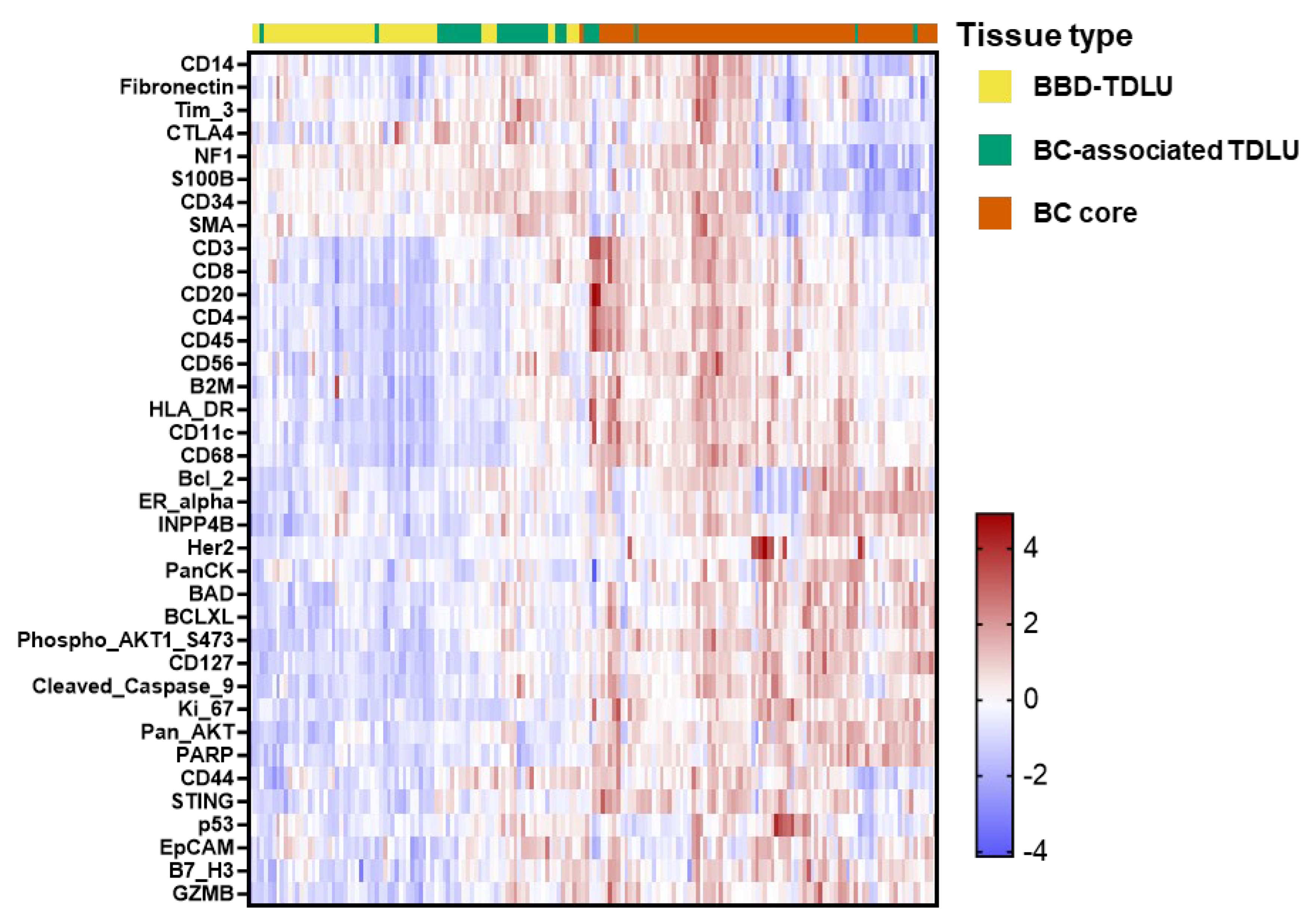

3.5. Spatial Tissue Type Contrasts Among Cases: BBD TDLUs, BC-Associated TDLUs, and BCs

3.6. Exploratory Case–Control Analyses in BBD-TDLUs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AH | Atypical hyperplasia |

| BC | Breast cancer |

| BBD | Benign breast disease |

| BCL2/BCL-XL | B-cell lymphoma 2/B-cell lymphoma extra-long isoform |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| DAB | 3,3′-diaminobenzidin |

| DAPI | 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| DSP | Digital Spatial Profiling |

| ER/PR/HER2 | Estrogen receptor/Progesterone receptor/Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| FFPE | Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and eosin |

| H-score | Histologic score (semi-quantitative immunostain metric) |

| HRP | Horseradish peroxidase |

| ICC | Intraclass correlation coefficient |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry (chromogenic) |

| IGF1R | Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor |

| LS-means | Least-squares means |

| MHC | Major histocompatibility complex |

| NK | Natural killer (cell) |

| OPAL | Tyramide-based multiplex immunofluorescence platform |

| QC | Quality control |

| ROI | Region of interest |

| SMA | Smooth muscle actin |

| STING | Stimulator of interferon genes |

| TDLU | Terminal duct lobular unit |

| TMA | Tissue microarray |

References

- Tice, J.A.; O’Meara, E.S.; Weaver, D.L.; Vachon, C.; Ballard-Barbash, R.; Kerlikowske, K. Benign breast disease, mammographic breast density, and the risk of breast cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013, 105, 1043–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, M.E.; Vierkant, R.A.; Winham, S.J.; Vachon, C.M.; Carter, J.M.; Pacheco-Spann, L.; Jensen, M.R.; McCauley, B.M.; Hoskin, T.L.; Seymour, L.; et al. Benign Breast Disease and Breast Cancer Risk in the Percutaneous Biopsy Era. JAMA Surg. 2024, 159, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeinomar, N.; Phillips, K.A.; Daly, M.B.; Milne, R.L.; Dite, G.S.; MacInnis, R.J.; Liao, Y.; Kehm, R.D.; Knight, J.A.; Southey, M.C.; et al. Benign breast disease increases breast cancer risk independent of underlying familial risk profile: Findings from a Prospective Family Study Cohort. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 145, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyrstad, S.W.; Yan, Y.; Fowler, A.M.; Colditz, G.A. Breast cancer risk associated with benign breast disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015, 149, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, M.; Schnitt, S.J.; Norton, L. Current management of lesions associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 12, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Owens, D.K.; Davidson, K.W.; Krist, A.H.; Barry, M.J.; Cabana, M.; Caughey, A.B.; Doubeni, C.A.; Epling, J.W., Jr.; Kubik, M.; et al. Medication Use to Reduce Risk of Breast Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2019, 322, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avila Cobos, F.; Vandesompele, J.; Mestdagh, P.; De Preter, K. Computational deconvolution of transcriptomics data from mixed cell populations. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 1969–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avila Cobos, F.; Alquicira-Hernandez, J.; Powell, J.E.; Mestdagh, P.; De Preter, K. Benchmarking of cell type deconvolution pipelines for transcriptomics data. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.M.; Liu, C.L.; Green, M.R.; Gentles, A.J.; Feng, W.; Xu, Y.; Hoang, C.D.; Diehn, M.; Alizadeh, A.A. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espina, V.; Milia, J.; Wu, G.; Cowherd, S.; Liotta, L.A. Laser capture microdissection. In Cell Imaging Techniques; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 319, pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.; Malhotra, L.; Dickerson, R.; Chaffee, S.; Sen, C.K.; Roy, S. Laser capture microdissection: Big data from small samples. Histol. Histopathol. 2015, 30, 1255–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radisky, D.C.; Visscher, D.W.; Frank, R.D.; Vierkant, R.A.; Winham, S.; Stallings-Mann, M.; Hoskin, T.L.; Nassar, A.; Vachon, C.M.; Denison, L.A.; et al. Natural history of age-related lobular involution and impact on breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2016, 155, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baer, H.J.; Collins, L.C.; Connolly, J.L.; Colditz, G.A.; Schnitt, S.J.; Tamimi, R.M. Lobule type and subsequent breast cancer risk: Results from the Nurses’ Health Studies. Cancer 2009, 115, 1404–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winham, S.J.; Wang, C.; Heinzen, E.P.; Bhagwate, A.; Liu, Y.; McDonough, S.J.; Stallings-Mann, M.L.; Frost, M.H.; Vierkant, R.A.; Denison, L.A.; et al. Somatic mutations in benign breast disease tissues and association with breast cancer risk. BMC Med. Genom. 2021, 14, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.A.; Rogers, M.A.; Khurana, K.K.; Meguid, M.M.; Numann, P.J. Estrogen receptor expression in benign breast epithelium and breast cancer risk. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1998, 90, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, S.J.; Oh, H.; Peterson, M.A.; Almendro, V.; Hu, R.; Bowden, M.; Lis, R.L.; Cotter, M.B.; Loda, M.; Barry, W.T.; et al. The Proliferative Activity of Mammary Epithelial Cells in Normal Tissue Predicts Breast Cancer Risk in Premenopausal Women. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 1926–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, M.; Louro, J.; Posso, M.; Vidal, C.; Bargallo, X.; Vazquez, I.; Quintana, M.J.; Alcantara, R.; Saladie, F.; Del Riego, J.; et al. Long-Term Risk of Breast Cancer after Diagnosis of Benign Breast Disease by Screening Mammography. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beca, F.; Kensler, K.; Glass, B.; Schnitt, S.J.; Tamimi, R.M.; Beck, A.H. EZH2 protein expression in normal breast epithelium and risk of breast cancer: Results from the Nurses’ Health Studies. Breast Cancer Res. 2017, 19, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodr, Z.G.; Sherman, M.E.; Pfeiffer, R.M.; Gierach, G.L.; Brinton, L.A.; Falk, R.T.; Patel, D.A.; Linville, L.M.; Papathomas, D.; Clare, S.E.; et al. Circulating sex hormones and terminal duct lobular unit involution of the normal breast. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2014, 23, 2765–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamimi, R.M.; Colditz, G.A.; Wang, Y.; Collins, L.C.; Hu, R.; Rosner, B.; Irie, H.Y.; Connolly, J.L.; Schnitt, S.J. Expression of IGF1R in normal breast tissue and subsequent risk of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011, 128, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degnim, A.C.; Hoskin, T.L.; Arshad, M.; Frost, M.H.; Winham, S.J.; Brahmbhatt, R.A.; Pena, A.; Carter, J.M.; Stallings-Mann, M.L.; Murphy, L.M.; et al. Alterations in the Immune Cell Composition in Premalignant Breast Tissue that Precede Breast Cancer Development. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 3945–3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis Lynn, B.C.; Lord, B.D.; Cora, R.; Pfeiffer, R.M.; Lawrence, S.; Zirpoli, G.; Bethea, T.N.; Palmer, J.R.; Gierach, G.L. Associations between quantitative measures of TDLU involution and breast tumor molecular subtypes among breast cancer cases in the Black Women’s Health Study: A case-case analysis. Breast Cancer Res. 2022, 24, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Guo, C.; Li, E.; Li, J.; Pfeiffer, R.M.; Guida, J.L.; Cora, R.; Hu, N.; Deng, J.; Figueroa, J.D.; et al. The relationship between terminal duct lobular unit features and mammographic density among Chinese breast cancer patients. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 145, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamimi, R.M.; Colditz, G.A.; Hazra, A.; Baer, H.J.; Hankinson, S.E.; Rosner, B.; Marotti, J.; Connolly, J.L.; Schnitt, S.J.; Collins, L.C. Traditional breast cancer risk factors in relation to molecular subtypes of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2012, 131, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.R.; Sherman, M.E.; Rimm, D.L.; Lissowska, J.; Brinton, L.A.; Peplonska, B.; Hewitt, S.M.; Anderson, W.F.; Szeszenia-Dabrowska, N.; Bardin-Mikolajczak, A.; et al. Differences in risk factors for breast cancer molecular subtypes in a population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2007, 16, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althuis, M.D.; Fergenbaum, J.H.; Garcia-Closas, M.; Brinton, L.A.; Madigan, M.P.; Sherman, M.E. Etiology of hormone receptor-defined breast cancer: A systematic review of the literature. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2004, 13, 1558–1568. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.; Bernstein, L.; Pike, M.C.; Ursin, G. Reproductive factors and breast cancer risk according to joint estrogen and progesterone receptor status: A meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Breast Cancer Res. 2006, 8, R43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mburu, W.; Guo, C.; Tian, Y.; Koka, H.; Fu, S.; Lu, N.; Li, E.; Li, J.; Cora, R.; Chan, A.; et al. Associations between quantitative measures of mammographic density and terminal ductal lobular unit involution in Chinese breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. 2024, 26, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hurley, G.; Sjostedt, E.; Rahman, A.; Li, B.; Kampf, C.; Ponten, F.; Gallagher, W.M.; Lindskog, C. Garbage in, garbage out: A critical evaluation of strategies used for validation of immunohistochemical biomarkers. Mol. Oncol. 2014, 8, 783–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallioniemi, O.P.; Wagner, U.; Kononen, J.; Sauter, G. Tissue microarray technology for high-throughput molecular profiling of cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001, 10, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, S.M. Tissue microarrays as a tool in the discovery and validation of tumor markers. In Tumor Biomarker Discovery; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2009; Volume 520, pp. 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauter, G.; Mirlacher, M. Tissue microarrays for predictive molecular pathology. J. Clin. Pathol. 2002, 55, 575–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kononen, J.; Bubendorf, L.; Kallioniemi, A.; Barlund, M.; Schraml, P.; Leighton, S.; Torhorst, J.; Mihatsch, M.J.; Sauter, G.; Kallioniemi, O.P. Tissue microarrays for high-throughput molecular profiling of tumor specimens. Nat. Med. 1998, 4, 844–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packeisen, J.; Korsching, E.; Herbst, H.; Boecker, W.; Buerger, H. Demystified…tissue microarray technology. Mol. Pathol. 2003, 56, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, M.; Radisky, D.C. Multiplex Digital Spatial Profiling in Breast Cancer Research: State-of-the-Art Technologies and Applications across the Translational Science Spectrum. Cancers 2024, 16, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decalf, J.; Albert, M.L.; Ziai, J. New tools for pathology: A user’s review of a highly multiplexed method for in situ analysis of protein and RNA expression in tissue. J. Pathol. 2019, 247, 650–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, S.; Lazcano, R.; Serrano, A.; Powell, S.; Kostousov, L.; Mehta, J.; Khan, K.; Lu, W.; Solis, L.M. Challenges and Opportunities for Immunoprofiling Using a Spatial High-Plex Technology: The NanoString GeoMx((R)) Digital Spatial Profiler. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 890410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, T.M.; Blank, C.U. A user’s perspective on GeoMx(TM) digital spatial profiling. Immunooncol. Technol. 2019, 1, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goltsev, Y.; Samusik, N.; Kennedy-Darling, J.; Bhate, S.; Hale, M.; Vazquez, G.; Black, S.; Nolan, G.P. Deep Profiling of Mouse Splenic Architecture with CODEX Multiplexed Imaging. Cell 2018, 174, 968–981.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keren, L.; Bosse, M.; Marquez, D.; Angoshtari, R.; Jain, S.; Varma, S.; Yang, S.R.; Kurian, A.; Van Valen, D.; West, R.; et al. A Structured Tumor-Immune Microenvironment in Triple Negative Breast Cancer Revealed by Multiplexed Ion Beam Imaging. Cell 2018, 174, 1373–1387.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, P.W.; Frankel, T.L.; Moutafi, M.; Rao, A.; Rimm, D.L.; Taube, J.M.; Thomas, D.; Chan, M.P.; Pantanowitz, L. Multiplex Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence: A Practical Update for Pathologists. Mod. Pathol. 2023, 36, 100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, C.R.; Ong, G.T.; Church, S.E.; Barker, K.; Danaher, P.; Geiss, G.; Hoang, M.; Jung, J.; Liang, Y.; McKay-Fleisch, J.; et al. Multiplex digital spatial profiling of proteins and RNA in fixed tissue. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, L.C.; Sellers, T.A.; Frost, M.H.; Lingle, W.L.; Degnim, A.C.; Ghosh, K.; Vierkant, R.A.; Maloney, S.D.; Pankratz, V.S.; Hillman, D.W.; et al. Benign breast disease and the risk of breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergholtz, H.; Carter, J.M.; Cesano, A.; Cheang, M.C.U.; Church, S.E.; Divakar, P.; Fuhrman, C.A.; Goel, S.; Gong, J.; Guerriero, J.L.; et al. Best Practices for Spatial Profiling for Breast Cancer Research with the GeoMx((R)) Digital Spatial Profiler. Cancers 2021, 13, 4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra, E.R.; Jiang, M.; Solis, L.; Mino, B.; Laberiano, C.; Hernandez, S.; Gite, S.; Verma, A.; Tetzlaff, M.; Haymaker, C.; et al. Procedural Requirements and Recommendations for Multiplex Immunofluorescence Tyramide Signal Amplification Assays to Support Translational Oncology Studies. Cancers 2020, 12, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgibbons, P.L.; Bradley, L.A.; Fatheree, L.A.; Alsabeh, R.; Fulton, R.S.; Goldsmith, J.D.; Haas, T.S.; Karabakhtsian, R.G.; Loykasek, P.A.; Marolt, M.J.; et al. Principles of analytic validation of immunohistochemical assays: Guideline from the College of American Pathologists Pathology and Laboratory Quality Center. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2014, 138, 1432–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldsmith, J.D.; Troxell, M.L.; Roy-Chowdhuri, S.; Colasacco, C.F.; Edgerton, M.E.; Fitzgibbons, P.L.; Fulton, R.; Haas, T.; Kandalaft, P.L.; Kalicanin, T.; et al. Principles of Analytic Validation of Immunohistochemical Assays: Guideline Update. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2024, 148, e111–e153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, E.C.; Wang, C.; Roman, K.A.; Hoyt, C.C. Multiplexed immunohistochemistry, imaging, and quantitation: A review, with an assessment of Tyramide signal amplification, multispectral imaging and multiplex analysis. Methods 2014, 70, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viratham Pulsawatdi, A.; Craig, S.G.; Bingham, V.; McCombe, K.; Humphries, M.P.; Senevirathne, S.; Richman, S.D.; Quirke, P.; Campo, L.; Domingo, E.; et al. A robust multiplex immunofluorescence and digital pathology workflow for the characterisation of the tumour immune microenvironment. Mol. Oncol. 2020, 14, 2384–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyt, C.C. Multiplex Immunofluorescence and Multispectral Imaging: Forming the Basis of a Clinical Test Platform for Immuno-Oncology. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 674747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taube, J.M.; Roman, K.; Engle, E.L.; Wang, C.; Ballesteros-Merino, C.; Jensen, S.M.; McGuire, J.; Jiang, M.; Coltharp, C.; Remeniuk, B.; et al. Multi-institutional TSA-amplified Multiplexed Immunofluorescence Reproducibility Evaluation (MITRE) Study. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e002197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuzick, J.; Sestak, I.; Forbes, J.F.; Dowsett, M.; Knox, J.; Cawthorn, S.; Saunders, C.; Roche, N.; Mansel, R.E.; von Minckwitz, G.; et al. Anastrozole for prevention of breast cancer in high-risk postmenopausal women (IBIS-II): An international, double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2014, 383, 1041–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuzick, J.; Sestak, I.; Bonanni, B.; Costantino, J.P.; Cummings, S.; DeCensi, A.; Dowsett, M.; Forbes, J.F.; Ford, L.; LaCroix, A.Z.; et al. Selective oestrogen receptor modulators in prevention of breast cancer: An updated meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet 2013, 381, 1827–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, P.E.; Ingle, J.N.; Ales-Martinez, J.E.; Cheung, A.M.; Chlebowski, R.T.; Wactawski-Wende, J.; McTiernan, A.; Robbins, J.; Johnson, K.C.; Martin, L.W.; et al. Exemestane for breast-cancer prevention in postmenopausal women. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 2381–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuzick, J.; Sestak, I.; Forbes, J.F.; Dowsett, M.; Cawthorn, S.; Mansel, R.E.; Loibl, S.; Bonanni, B.; Evans, D.G.; Howell, A.; et al. Use of anastrozole for breast cancer prevention (IBIS-II): Long-term results of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, W.H.; Pages, F.; Sautes-Fridman, C.; Galon, J. The immune contexture in human tumours: Impact on clinical outcome. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dieci, M.V.; Radosevic-Robin, N.; Fineberg, S.; van den Eynden, G.; Ternes, N.; Penault-Llorca, F.; Pruneri, G.; D’Alfonso, T.M.; Demaria, S.; Castaneda, C.; et al. Update on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer, including recommendations to assess TILs in residual disease after neoadjuvant therapy and in carcinoma in situ: A report of the International Immuno-Oncology Biomarker Working Group on Breast Cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2018, 52, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgado, R.; Denkert, C.; Demaria, S.; Sirtaine, N.; Klauschen, F.; Pruneri, G.; Wienert, S.; Van den Eynden, G.; Baehner, F.L.; Penault-Llorca, F.; et al. The evaluation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer: Recommendations by an International TILs Working Group 2014. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loi, S.; Drubay, D.; Adams, S.; Pruneri, G.; Francis, P.A.; Lacroix-Triki, M.; Joensuu, H.; Dieci, M.V.; Badve, S.; Demaria, S.; et al. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes and Prognosis: A Pooled Individual Patient Analysis of Early-Stage Triple-Negative Breast Cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo, K.A.; Heaphy, C.M.; Mai, M.; Vargas, K.M.; Jones, A.C.; Vo, P.; Butler, K.S.; Joste, N.E.; Bisoffi, M.; Griffith, J.K. Markers of fibrosis and epithelial to mesenchymal transition demonstrate field cancerization in histologically normal tissue adjacent to breast tumors. Int. J. Cancer 2011, 129, 1310–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Peng, F.; Ai, L.; Mu, S.; Li, Y.; Yang, C.; Hu, Y. Tumor-infiltrating B cells as a favorable prognostic biomarker in breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Lu, F.; Lyu, K.; Chang, A.E.; Li, Q. Emerging concepts regarding pro- and anti tumor properties of B cells in tumor immunity. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 881427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerekes, D.; Visscher, D.W.; Hoskin, T.L.; Radisky, D.C.; Brahmbhatt, R.D.; Pena, A.; Frost, M.H.; Arshad, M.; Stallings-Mann, M.; Winham, S.J.; et al. CD56+ immune cell infiltration and MICA are decreased in breast lobules with fibrocystic changes. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 167, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lochhead, P.; Chan, A.T.; Nishihara, R.; Fuchs, C.S.; Beck, A.H.; Giovannucci, E.; Ogino, S. Etiologic field effect: Reappraisal of the field effect concept in cancer predisposition and progression. Mod. Pathol. 2015, 28, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dotto, G.P. Multifocal epithelial tumors and field cancerization: Stroma as a primary determinant. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 1446–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtius, K.; Wright, N.A.; Graham, T.A. An evolutionary perspective on field cancerization. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aran, D.; Camarda, R.; Odegaard, J.; Paik, H.; Oskotsky, B.; Krings, G.; Goga, A.; Sirota, M.; Butte, A.J. Comprehensive analysis of normal adjacent to tumor transcriptomes. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, A.; Dolled-Filhart, M.; Camp, R.L.; Rimm, D.L. Automated quantitative analysis (AQUA) of in situ protein expression, antibody concentration, and prognosis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2005, 97, 1808–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntasell, A.; Servitja, S.; Cabo, M.; Bermejo, B.; Perez-Buira, S.; Rojo, F.; Costa-Garcia, M.; Arpi, O.; Moraru, M.; Serrano, L.; et al. High Numbers of Circulating CD57+ NK Cells Associate with Resistance to HER2-Specific Therapeutic Antibodies in HER2+ Primary Breast Cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2019, 7, 1280–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Weighted Kappa (95% CI) Exact Agreement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel | Biomarker | BBD TDLUs | BC | BC-Associated TDLUs |

| IHC | BCL-2 H score | 0.05 (−0.05–0.14) 44.7% | 0.61 (0.49–0.72) 67.8% | 0.15 (−0.07–0.37) 47.7% |

| IHC | CD20 percent cells positive | 0.09 (−0.02–019) 41.4% | 0.22 (0.09–0.34) 53.6% | N/A 48.7% |

| IHC | CD3 percent cells positive | 0.17 (0.07–0.27) 47.1% | 0.20 (0.06–0.34) 44.1% | 0.26 (0.28–0.45) 55.1% |

| IHC | CD45 percent cells positive | 0.16 (0.05–0.27) 48.5% | 0.27 (0.14–0.40) 47.8% | 0.43 (0.05–0.48) 55.1% |

| IHC | ER percent cells positive | 0.32 (0.21–0.43) 61.8% | 0.73 (0.62–0.84) 80.4% | 0.26 (0.04–0.49) 53.1% |

| IHC | PR percent cells positive | 0.24 (0.14–0.35) 54.1% | 0.53 (0.42–0.65) 60.8% | 0.26 (0.06–0.46) 48.2% |

| OPAL | CD4 cell density | 0.0 (−0.09–0.09) 41.7% | 0.14 (−0.00–0.28) 42.3% | N/A 46.9% |

| OPAL | CD68 cell density | 0.13 (0.04–0.22) 50.3% | −0.02 (−0.19–0.15) 48.6% | N/A 51.6% |

| OPAL | CD8 cell density | 0.07 (−0.01–0.16) 42.7% | 0.10 (−0.03–0.22) 44.1% | 0.10 (−0.06–0.27) 42.2% |

| OPAL | Ki67 cell density | 0.10 (0.01–0.20) 47.7% | N/A 68.4% | N/A 46.9% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sherman, M.E.; Carter, J.C.; Vierkant, R.A.; Stallings-Mann, M.; Pacheco-Spann, L.; Winham, S.J.; Vachon, C.M.; Wang, C.; Jensen, M.R.; Troester, M.A.; et al. Tissue Microarray-Based Digital Spatial Profiling of Benign Breast Lobules and Breast Cancers: Feasibility, Biological Coherence, and Cross-Platform Benchmarks. Cancers 2025, 17, 3797. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233797

Sherman ME, Carter JC, Vierkant RA, Stallings-Mann M, Pacheco-Spann L, Winham SJ, Vachon CM, Wang C, Jensen MR, Troester MA, et al. Tissue Microarray-Based Digital Spatial Profiling of Benign Breast Lobules and Breast Cancers: Feasibility, Biological Coherence, and Cross-Platform Benchmarks. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3797. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233797

Chicago/Turabian StyleSherman, Mark E., Jodi C. Carter, Robert A. Vierkant, Melody Stallings-Mann, Laura Pacheco-Spann, Stacey J. Winham, Celine M. Vachon, Chen Wang, Matthew R. Jensen, Melissa A. Troester, and et al. 2025. "Tissue Microarray-Based Digital Spatial Profiling of Benign Breast Lobules and Breast Cancers: Feasibility, Biological Coherence, and Cross-Platform Benchmarks" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3797. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233797

APA StyleSherman, M. E., Carter, J. C., Vierkant, R. A., Stallings-Mann, M., Pacheco-Spann, L., Winham, S. J., Vachon, C. M., Wang, C., Jensen, M. R., Troester, M. A., Degnim, A. C., Thompson, E. A., Kachergus, J., Shi, J., & Radisky, D. C. (2025). Tissue Microarray-Based Digital Spatial Profiling of Benign Breast Lobules and Breast Cancers: Feasibility, Biological Coherence, and Cross-Platform Benchmarks. Cancers, 17(23), 3797. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233797