Plasma Fibronectin Drives Macrophage Elongation via Integrin β3–Tie2 Axis in Blood Clots

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Metastasis Model

2.2. 3-Dimensional Cell Culture

2.3. Analysis of Cell Morphology

2.4. Gene Silencing

2.5. Real-Time PCR

2.6. Cell Adhesion Assay

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

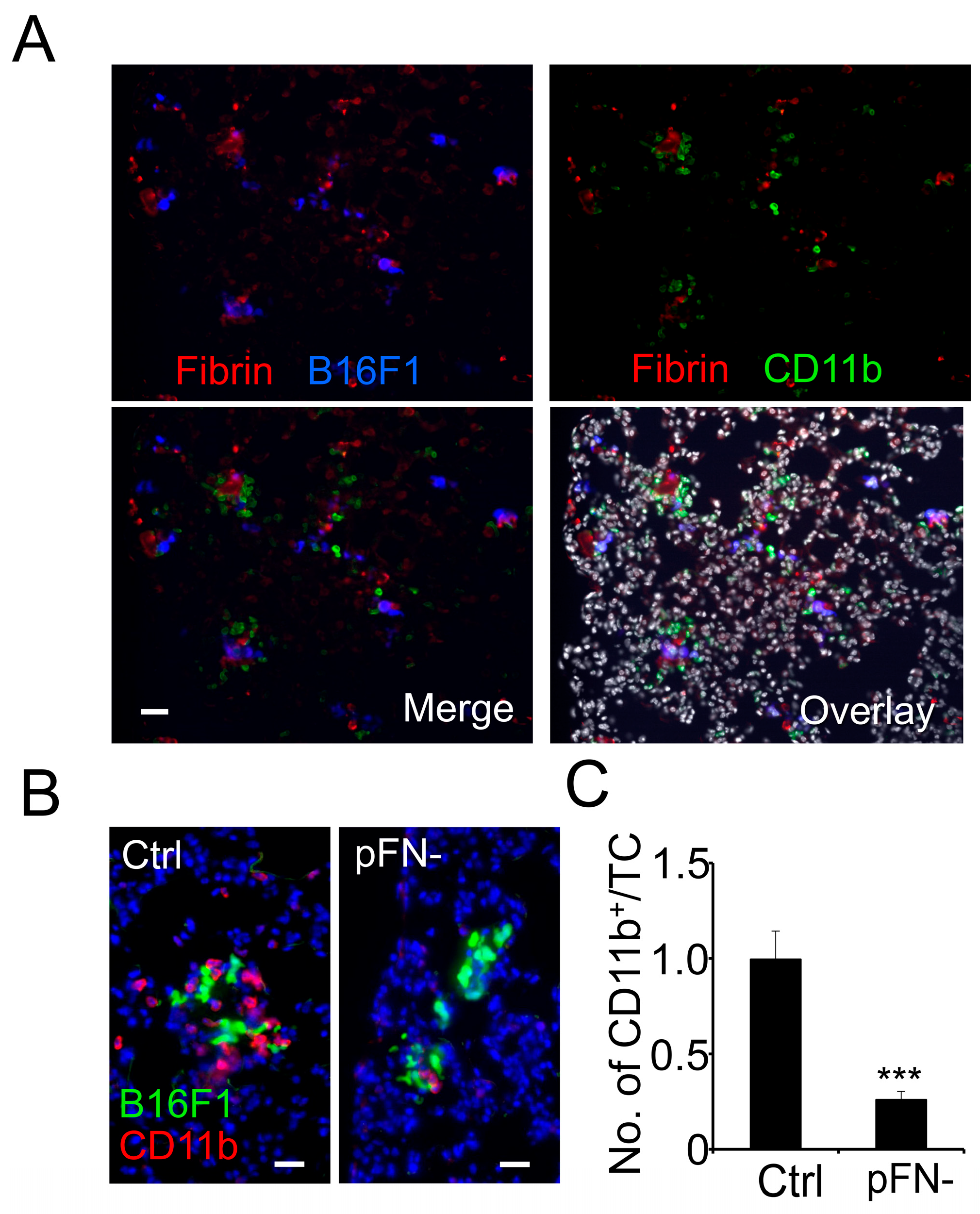

3.1. Homing of Myeloid Cells to Clot-Associated Tumor Cells Is Reduced in pFN-Deficient Mice

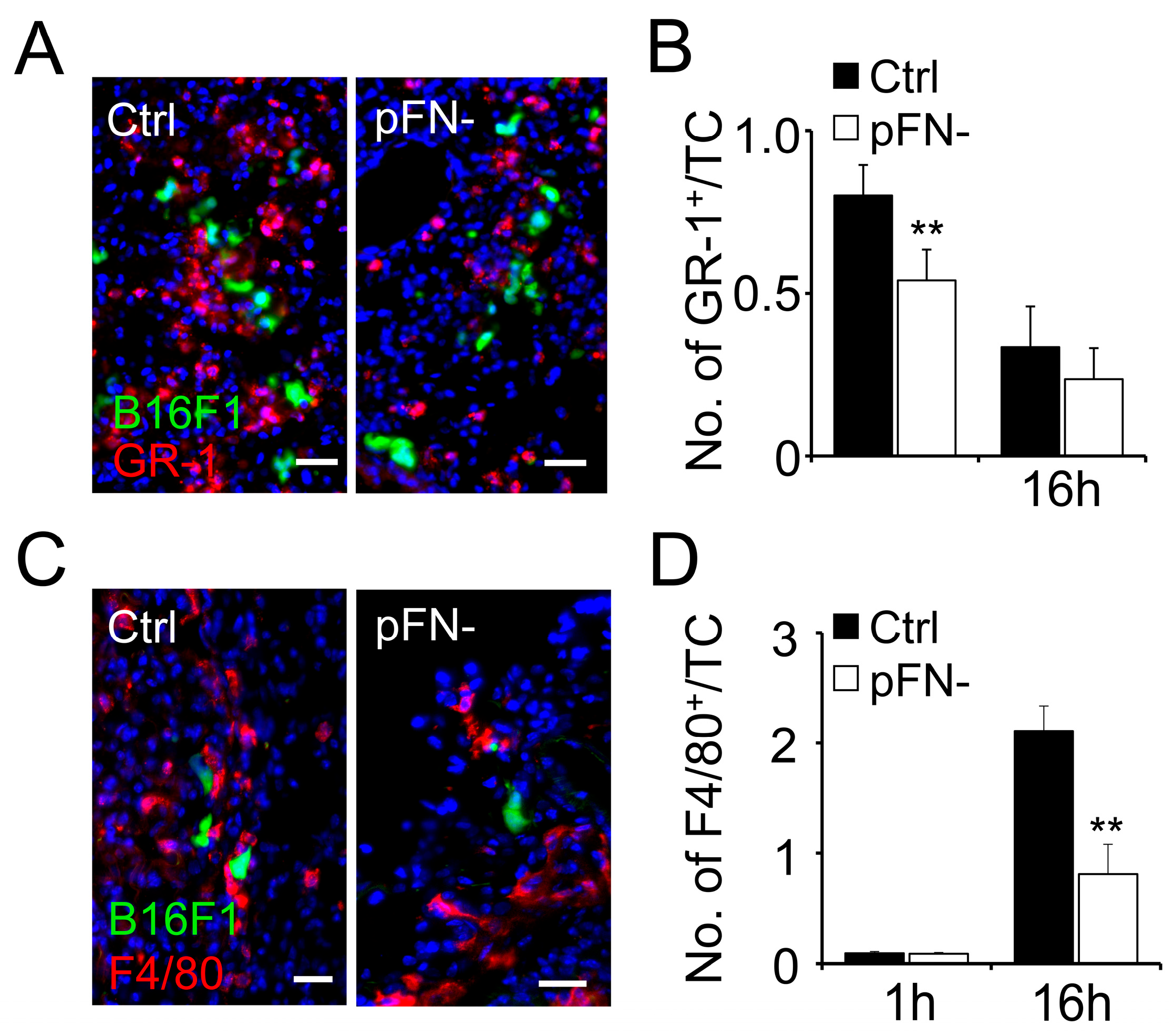

3.2. Association of Granulocytes and Macrophages with Metastatic Tumor Cells Is Reduced in pFN-Deficient Mice

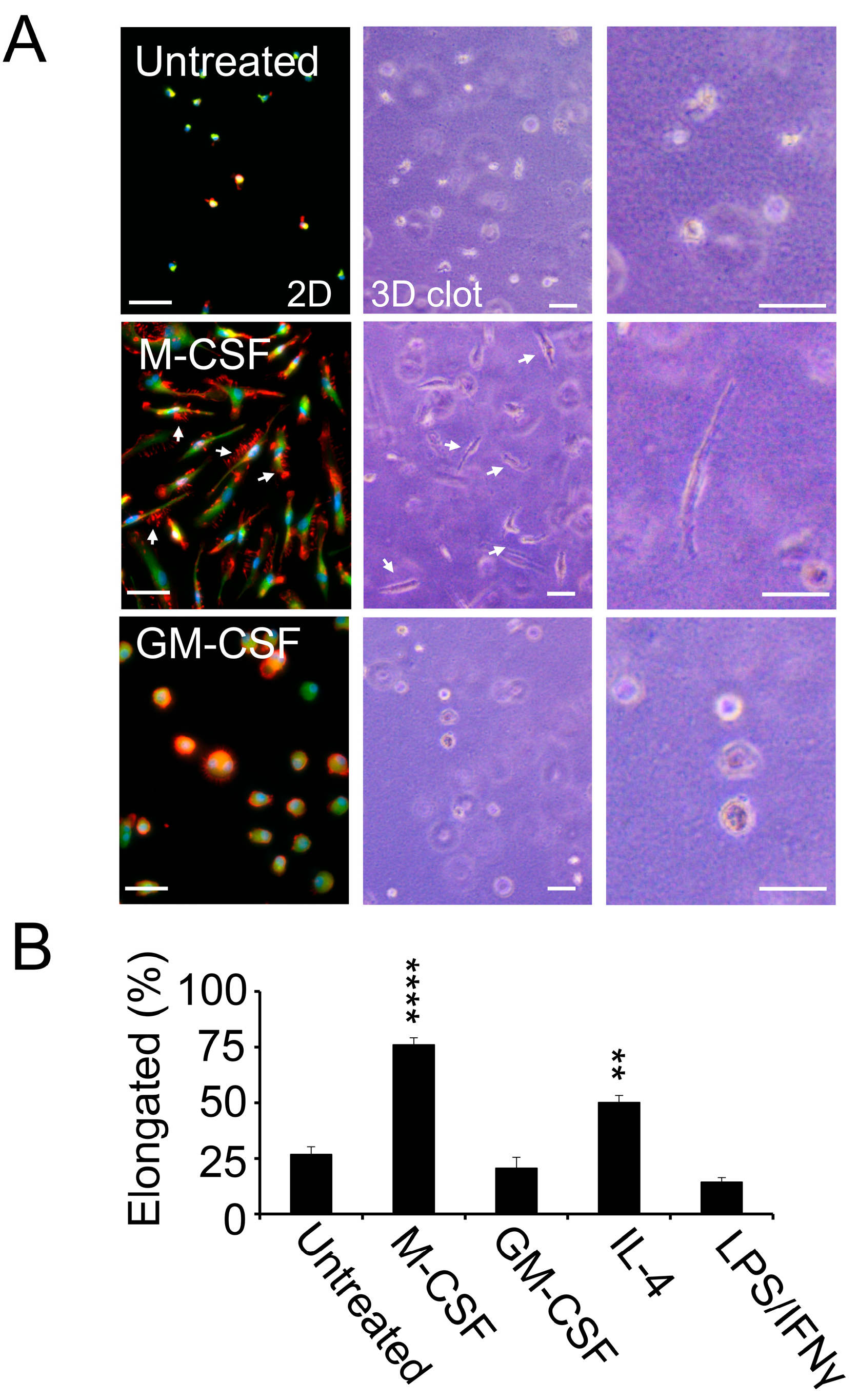

3.3. M2-Polarized Macrophages Invade Clotted Plasma In Vitro

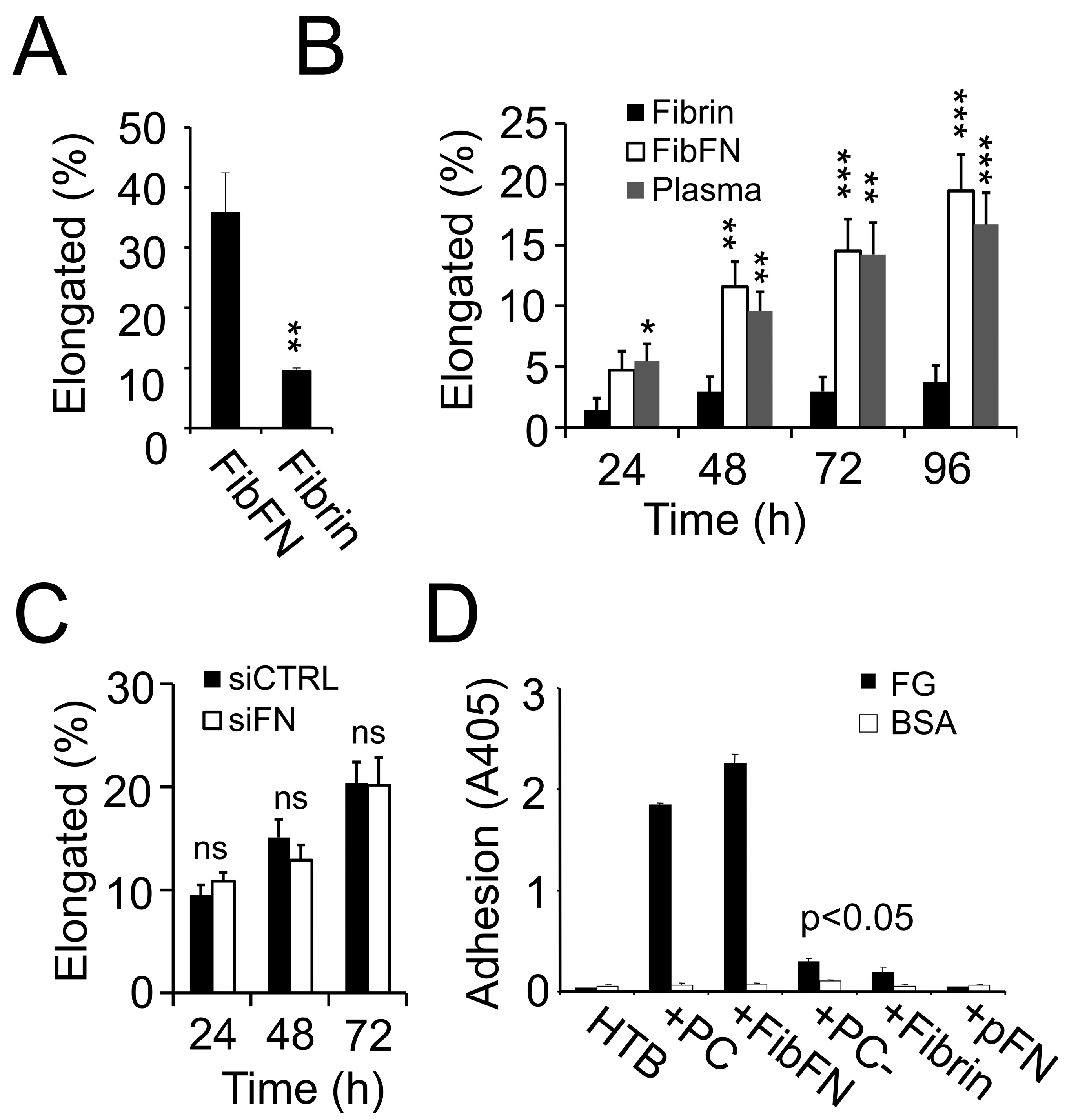

3.4. pFN Supports a Pro-Invasive M2 Macrophage Phenotype

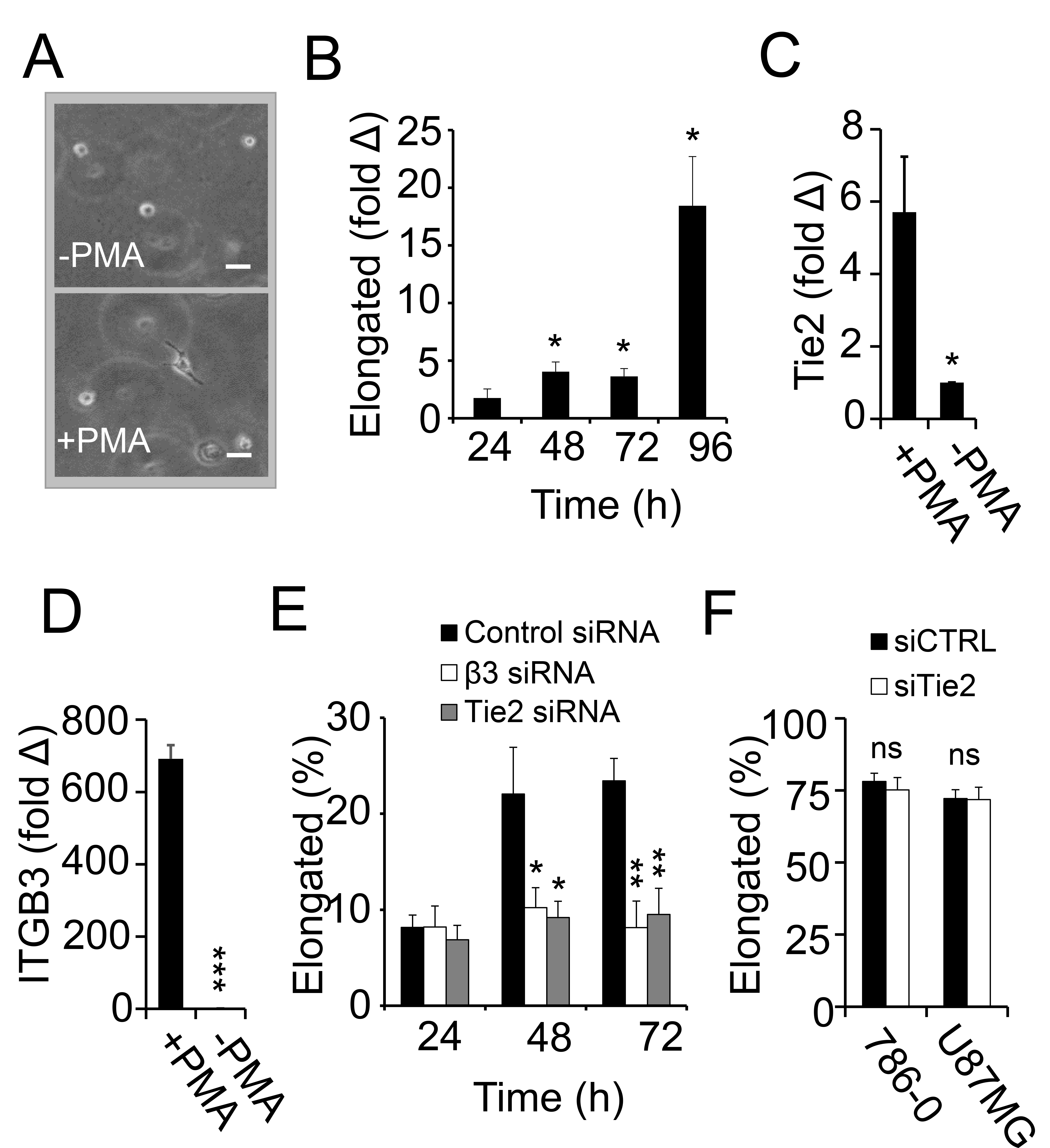

3.5. Macrophage Polarization and Invasion in Fibrin–Fibronectin Is Supported by Integrin αvβ3 and Tie2

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chambers, A.F.; Groom, A.C.; MacDonald, I.C. Dissemination and growth of cancer cells in metastatic sites. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, R.D.; Old, L.J.; Smyth, M.J. Cancer immunoediting: Integrating immunity’s roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science 2011, 331, 1565–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, R.; Lu, K.V.; Petritsch, C.; Liu, P.; Ganss, R.; Passegue, E.; Song, H.; Vandenberg, S.; Johnson, R.S.; Werb, Z.; et al. HIF1alpha induces the recruitment of bone marrow-derived vascular modulatory cells to regulate tumor angiogenesis and invasion. Cancer Cell 2008, 13, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schouppe, E.; De Baetselier, P.; Van Ginderachter, J.A.; Sarukhan, A. Instruction of myeloid cells by the tumor microenvironment: Open questions on the dynamics and plasticity of different tumor-associated myeloid cell populations. Oncoimmunology 2012, 1, 1135–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galon, J.; Costes, A.; Sanchez-Cabo, F.; Kirilovsky, A.; Mlecnik, B.; Lagorce-Pages, C.; Tosolini, M.; Camus, M.; Berger, A.; Wind, P.; et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science 2006, 313, 1960–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Takahashi, H.; Lin, W.W.; Descargues, P.; Grivennikov, S.; Kim, Y.; Luo, J.L.; Karin, M. Carcinoma-produced factors activate myeloid cells through TLR2 to stimulate metastasis. Nature 2009, 457, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; DeBusk, L.M.; Fukuda, K.; Fingleton, B.; Green-Jarvis, B.; Shyr, Y.; Matrisian, L.M.; Carbone, D.P.; Lin, P.C. Expansion of myeloid immune suppressor Gr+CD11b+ cells in tumor-bearing host directly promotes tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell 2004, 6, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, P.C.; Quiceno, D.G.; Zabaleta, J.; Ortiz, B.; Zea, A.H.; Piazuelo, M.B.; Delgado, A.; Correa, P.; Brayer, J.; Sotomayor, E.M.; et al. Arginase I production in the tumor microenvironment by mature myeloid cells inhibits T-cell receptor expression and antigen-specific T-cell responses. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 5839–5849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steidl, C.; Lee, T.; Shah, S.P.; Farinha, P.; Han, G.; Nayar, T.; Delaney, A.; Jones, S.J.; Iqbal, J.; Weisenburger, D.D.; et al. Tumor-associated macrophages and survival in classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 875–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Palma, M.; Venneri, M.A.; Galli, R.; Sergi Sergi, L.; Politi, L.S.; Sampaolesi, M.; Naldini, L. Tie2 identifies a hematopoietic lineage of proangiogenic monocytes required for tumor vessel formation and a mesenchymal population of pericyte progenitors. Cancer Cell 2005, 8, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, J.S.; Talmage, K.E.; Massari, J.V.; La Jeunesse, C.M.; Flick, M.J.; Kombrinck, K.W.; Jirouskova, M.; Degen, J.L. Platelets and fibrin(ogen) increase metastatic potential by impeding natural killer cell-mediated elimination of tumor cells. Blood 2005, 105, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Knowles, L.M.; Gurski, L.A.; Engel, C.; Gnarra, J.R.; Maranchie, J.K.; Pilch, J. Integrin alphavbeta3 and fibronectin upregulate Slug in cancer cells to promote clot invasion and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 6175–6184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, L.M.; Malik, G.; Pilch, J. Plasma Fibronectin Promotes Tumor Cell Survival and Invasion through Regulation of Tie2. J. Cancer 2013, 4, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, G.; Knowles, L.M.; Dhir, R.; Xu, S.; Yang, S.; Ruoslahti, E.; Pilch, J. Plasma fibronectin promotes lung metastasis by contributions to fibrin clots and tumor cell invasion. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 4327–4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinbrecher, K.A.; Horowitz, N.A.; Blevins, E.A.; Barney, K.A.; Shaw, M.A.; Harmel-Laws, E.; Finkelman, F.D.; Flick, M.J.; Pinkerton, M.D.; Talmage, K.E.; et al. Colitis-associated cancer is dependent on the interplay between the hemostatic and inflammatory systems and supported by integrin alpha(M)beta(2) engagement of fibrinogen. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 2634–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, E.A.; Schneider, J.G.; Baroni, T.E.; Uluckan, O.; Heller, E.; Hurchla, M.A.; Deng, H.; Floyd, D.; Berdy, A.; Prior, J.L.; et al. Dissection of platelet and myeloid cell defects by conditional targeting of the beta3-integrin subunit. FASEB J. 2010, 24, 1117–1127. [Google Scholar]

- Kopec, A.K.; Abrahams, S.R.; Thornton, S.; Palumbo, J.S.; Mullins, E.S.; Divanovic, S.; Weiler, H.; Owens, A.P., 3rd; Mackman, N.; Goss, A.; et al. Thrombin promotes diet-induced obesity through fibrin-driven inflammation. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 3152–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopec, A.K.; Joshi, N.; Cline-Fedewa, H.; Wojcicki, A.V.; Ray, J.L.; Sullivan, B.P.; Froehlich, J.E.; Johnson, B.F.; Flick, M.J.; Luyendyk, J.P. Fibrin(ogen) drives repair after acetaminophen-induced liver injury via leukocyte α(M)β(2) integrin-dependent upregulation of Mmp12. J. Hepatol. 2017, 66, 787–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, L.M.; Kagiri, D.; Bernard, M.; Schwarz, E.C.; Eichler, H.; Pilch, J. Macrophage Polarization is Deregulated in Haemophilia. Thromb. Haemost. 2019, 119, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajac, E.; Schweighofer, B.; Kupriyanova, T.A.; Juncker-Jensen, A.; Minder, P.; Quigley, J.P.; Deryugina, E.I. Angiogenic capacity of M1- and M2-polarized macrophages is determined by the levels of TIMP-1 complexed with their secreted proMMP-9. Blood 2013, 122, 4054–4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matikainen, S.; Hurme, M. Comparison of retinoic acid and phorbol myristate acetate as inducers of monocytic differentiation. Int. J. Cancer 1994, 57, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWhorter, F.Y.; Wang, T.; Nguyen, P.; Chung, T.; Liu, W.F. Modulation of macrophage phenotype by cell shape. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 17253–17258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, S.A.; Lee, L.; Wilson, C.L.; Schwarzbauer, J.E. Covalent cross-linking of fibronectin to fibrin is required for maximal cell adhesion to a fibronectin-fibrin matrix. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 24999–25005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, L.M.; Wolter, C.; Linsler, S.; Müller, S.; Urbschat, S.; Ketter, R.; Müller, A.; Zhou, X.; Qu, B.; Senger, S.; et al. Clotting Promotes Glioma Growth and Infiltration Through Activation of Focal Adhesion Kinase. Cancer Res. Commun. 2024, 4, 3124–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labelle, M.; Begum, S.; Hynes, R.O. Direct signaling between platelets and cancer cells induces an epithelial-mesenchymal-like transition and promotes metastasis. Cancer Cell 2011, 20, 576–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Cao, X. Characteristics and Significance of the Pre-metastatic Niche. Cancer Cell 2016, 30, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.K.; Rafalski, V.A.; Meyer-Franke, A.; Adams, R.A.; Poda, S.B.; Rios Coronado, P.E.; Pedersen, L.; Menon, V.; Baeten, K.M.; Sikorski, S.L.; et al. Fibrin-targeting immunotherapy protects against neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Nat. Immunol. 2018, 19, 1212–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakai, T.; Johnson, K.J.; Murozono, M.; Sakai, K.; Magnuson, M.A.; Wieloch, T.; Cronberg, T.; Isshiki, A.; Erickson, H.P.; Fässler, R. Plasma fibronectin supports neuronal survival and reduces brain injury following transient focal cerebral ischemia but is not essential for skin-wound healing and hemostasis. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, M.; Harger, A.; Lenkowski, A.; Hedner, U.; Roberts, H.R.; Monroe, D.M. Cutaneous wound healing is impaired in hemophilia B. Blood 2006, 108, 3053–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, M.J.; LaJeunesse, C.M.; Talmage, K.E.; Witte, D.P.; Palumbo, J.S.; Pinkerton, M.D.; Thornton, S.; Degen, J.L. Fibrin(ogen) exacerbates inflammatory joint disease through a mechanism linked to the integrin alphaMbeta2 binding motif. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 3224–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.K.; Siprashvili, Z.; Khavari, P.A. Advances in skin grafting and treatment of cutaneous wounds. Science 2014, 346, 941–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskaran, J.P.; Weldy, A.; Guarin, J.; Munoz, G.; Shpilker, P.H.; Kotlik, M.; Subbiah, N.; Wishart, A.; Peng, Y.; Miller, M.A.; et al. Cell shape, and not 2D migration, predicts extracellular matrix-driven 3D cell invasion in breast cancer. APL Bioeng. 2020, 4, 026105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotary, K.B.; Allen, E.D.; Brooks, P.C.; Datta, N.S.; Long, M.W.; Weiss, S.J. Membrane type I matrix metalloproteinase usurps tumor growth control imposed by the three-dimensional extracellular matrix. Cell 2003, 114, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luu, T.; Liu, W. Regulation of Macrophages by Extracellular Matrix Composition and Adhesion Geometry. Regen. Eng. Transl. Med. 2018, 4, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccio, R.; Takeshita, S.; Colaianni, G.; Chappel, J.; Zallone, A.; Teitelbaum, S.L.; Ross, F.P. M-CSF regulates the cytoskeleton via recruitment of a multimeric signaling complex to c-Fms Tyr-559/697/721. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 18991–18999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidzadeh, K.; Belew, A.T.; El-Sayed, N.M.; Mosser, D.M. The transition of M-CSF-derived human macrophages to a growth-promoting phenotype. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 5460–5472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sargent, E.R.; Gomella, L.G.; Belldegrun, A.; Linehan, W.M.; Kasid, A. Epidermal growth factor receptor gene expression in normal human kidney and renal cell carcinoma. J. Urol. 1989, 142, 1364–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Ding, Y.; Li, Y.; Luo, W.M.; Zhang, Z.F.; Snider, J.; Vandenbeldt, K.; Qian, C.N.; Teh, B.T. Sunitinib acts primarily on tumor endothelium rather than tumor cells to inhibit the growth of renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 1053–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kim, J.; Mueller, A.C.; Dey, B.; Yang, Y.; Lee, D.H.; Hachmann, J.; Finderle, S.; Park, D.M.; Christensen, J.; et al. Multiple receptor tyrosine kinases converge on microRNA-134 to control KRAS, STAT5B, and glioblastoma. Cell Death Differ. 2014, 21, 720–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Master, Z.; Jones, N.; Tran, J.; Jones, J.; Kerbel, R.S.; Dumont, D.J. Dok-R plays a pivotal role in angiopoietin-1-dependent cell migration through recruitment and activation of Pak. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 5919–5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontos, C.D.; Stauffer, T.P.; Yang, W.P.; York, J.D.; Huang, L.; Blanar, M.A.; Meyer, T.; Peters, K.G. Tyrosine 1101 of Tie2 is the major site of association of p85 and is required for activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Akt. Mol Cell Biol 1998, 18, 4131–4140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cascone, I.; Napione, L.; Maniero, F.; Serini, G.; Bussolino, F. Stable interaction between alpha5beta1 integrin and Tie2 tyrosine kinase receptor regulates endothelial cell response to Ang-1. J. Cell Biol. 2005, 170, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felcht, M.; Luck, R.; Schering, A.; Seidel, P.; Srivastava, K.; Hu, J.; Bartol, A.; Kienast, Y.; Vettel, C.; Loos, E.K.; et al. Angiopoietin-2 differentially regulates angiogenesis through TIE2 and integrin signaling. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 1991–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Knowles, L.M.; Eichler, H.; Pilch, J. Plasma Fibronectin Drives Macrophage Elongation via Integrin β3–Tie2 Axis in Blood Clots. Cancers 2025, 17, 3780. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233780

Knowles LM, Eichler H, Pilch J. Plasma Fibronectin Drives Macrophage Elongation via Integrin β3–Tie2 Axis in Blood Clots. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3780. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233780

Chicago/Turabian StyleKnowles, Lynn M., Hermann Eichler, and Jan Pilch. 2025. "Plasma Fibronectin Drives Macrophage Elongation via Integrin β3–Tie2 Axis in Blood Clots" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3780. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233780

APA StyleKnowles, L. M., Eichler, H., & Pilch, J. (2025). Plasma Fibronectin Drives Macrophage Elongation via Integrin β3–Tie2 Axis in Blood Clots. Cancers, 17(23), 3780. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233780