Structured Symptom Assessment in Dermato-Oncology Patients—A Prospective Observational Study of the Usability of a Symptom Questionnaire

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- In some cases, patients may be unaware that symptoms can indicate disease progression or be a relevant side effect of therapy.

- -

- They may be afraid to report symptoms because they fear the consequences, such as disease progression and subsequent termination of therapy, or approaching the end of life.

- -

- They feel uncomfortable discussing intimate problems such as diarrhoea or loss of libido.

- -

- They do not recognise a symptom as such (e.g., fatigue or sleep disorders).

- -

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- Treatment at the Skin Cancer Centre

- -

- Confirmed diagnosis of a malignant dermatological tumour

- -

- Sufficient knowledge of German and the ability to read and write.

- -

- Age ≤ 10 years

- -

- Impaired cognition

- -

- Insufficient knowledge of German

- -

- Incomplete questionnaire.

2.1. Development of the Questionnaire

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

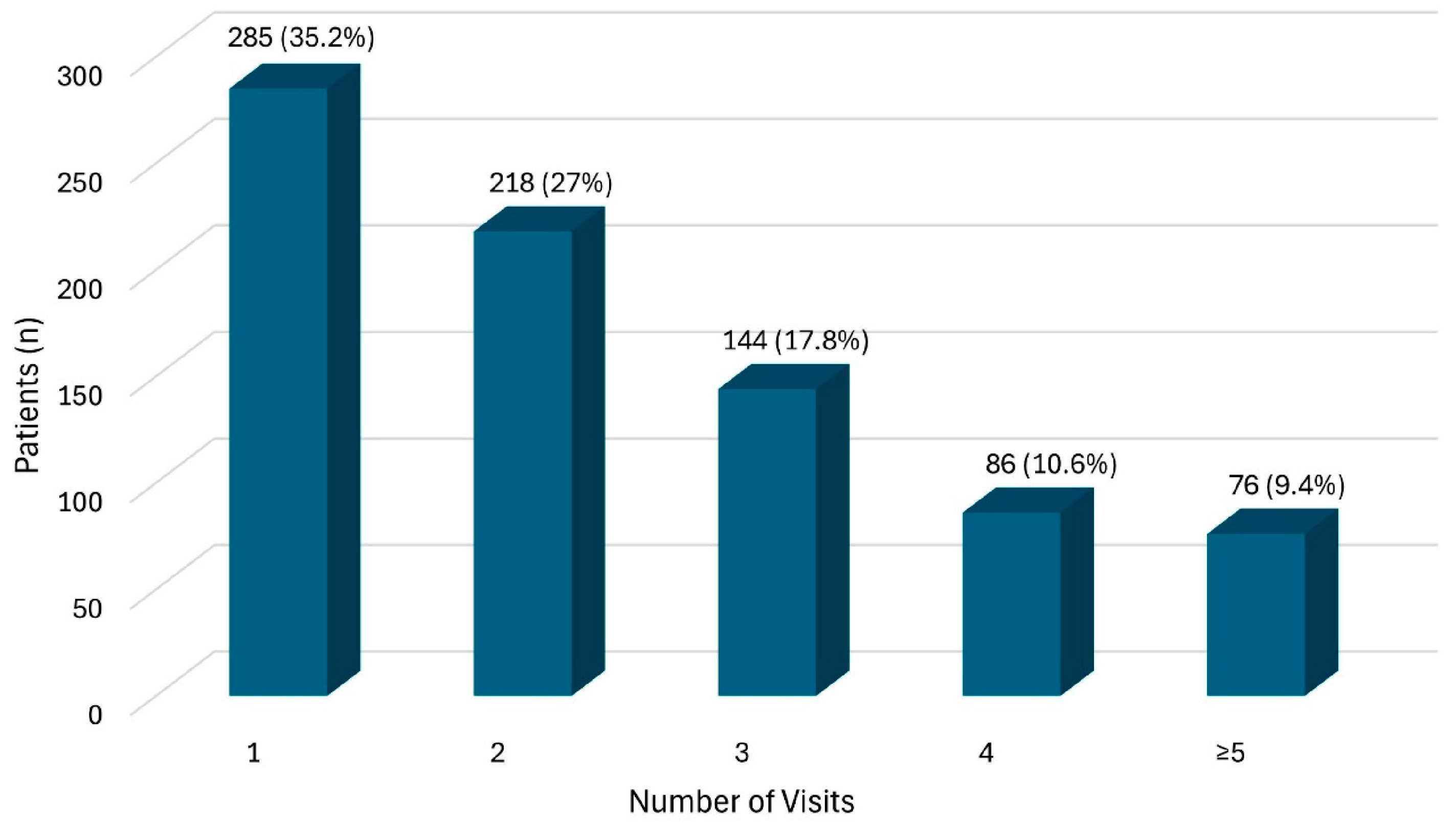

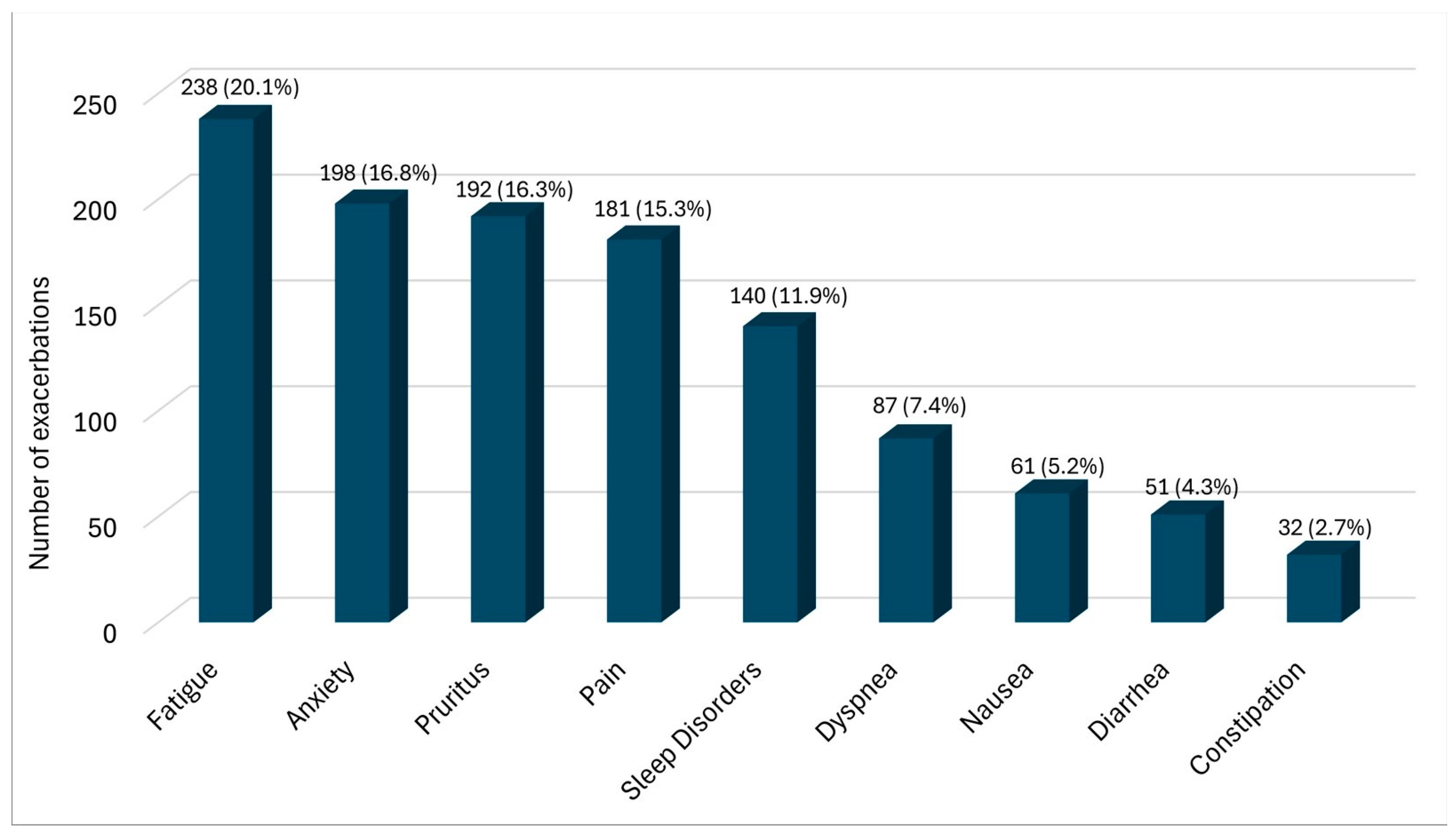

3.2. Descriptive Analysis

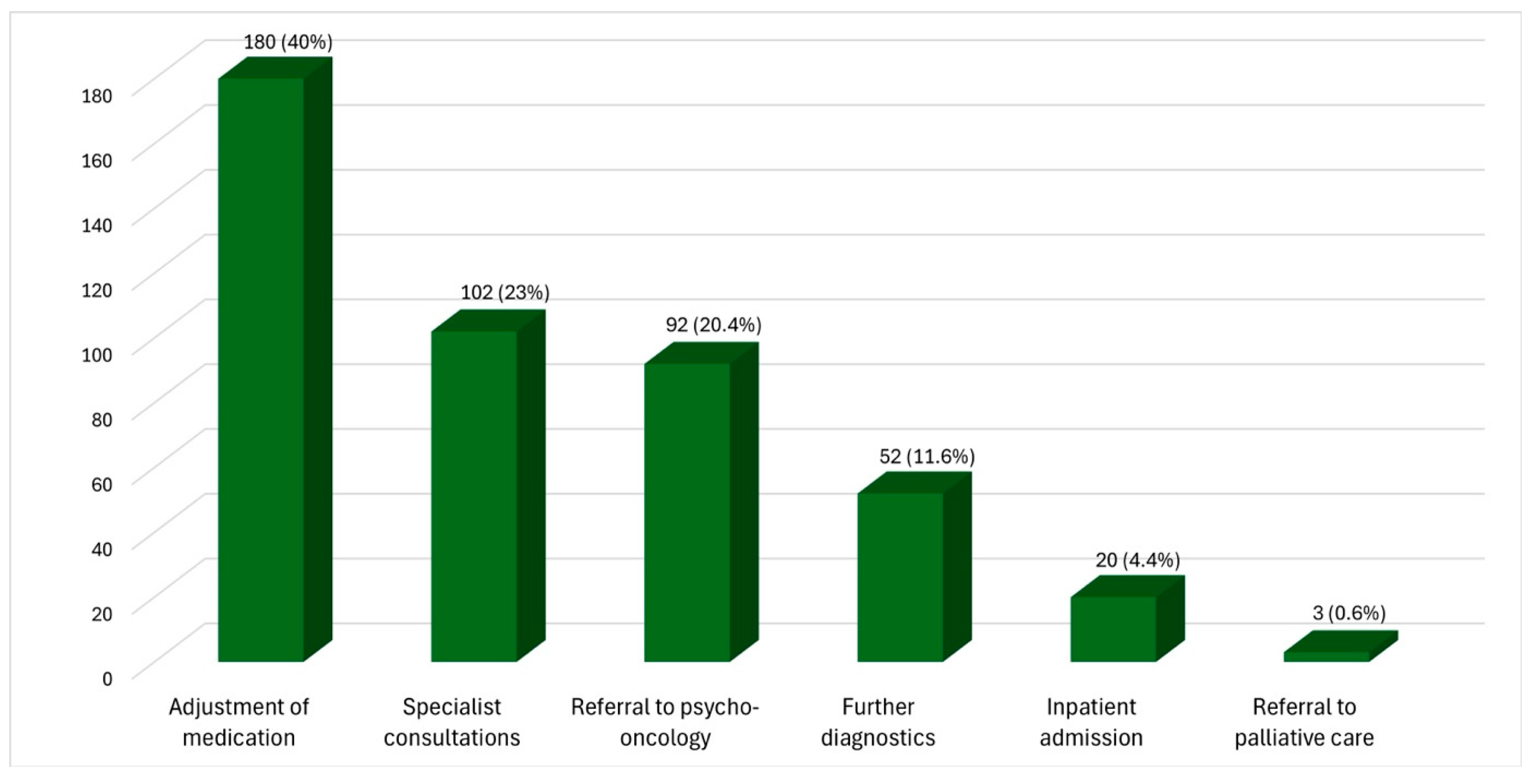

3.3. Response to Reported Increase in Symptoms

3.4. Effect of Measures Taken

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roshan, M.; Rao, A.P. A study on relative contributions of the history, physical examination and investigations in making medical diagnosis. J. Assoc. Physicians India 2000, 48, 771–775. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, M.C.; Holbrook, J.H.; Von Hales, D.; Smith, N.L.; Staker, L.V. Contributions of the history, physical examination, and laboratory investigation in making medical diagnoses. West. J. Med. 1992, 156, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampton, J.R.; Harrison, M.J.; Mitchell, J.R.; Prichard, J.S.; Seymour, C. Relative contributions of history-taking, physical examination, and laboratory investigation to diagnosis and management of medical outpatients. BMJ 1975, 2, 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, K.; Petterson, S.; Wingrove, P.; Miller, B.; Klink, K. You can’t treat what you don’t diagnose: An analysis of the recognition of somatic presentations of depression and anxiety in primary care. Fam. Syst. Health 2016, 34, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleeland, C.; Von Moos, R.; Walker, M.S.; Wang, Y.; Gao, J.; Chavez-MacGregor, M.; Liede, A.; Arellano, J.; Balakumaran, A.; Qian, Y. Burden of symptoms associated with development of metastatic bone disease in patients with breast cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 3557–3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, L.A.; Maddocks, M.; Evans, C.; Davidson, M.; Hicks, S.; Higginson, I.J. Palliative Care and the Management of Common Distressing Symptoms in Advanced Cancer: Pain, Breathlessness, Nausea and Vomiting, and Fatigue. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volberg, C.; Schrade, S.; Heers, H.; Carrasco, A.J.P.; Morin, A.; Gschnell, M. End-of-life wishes and care planning for patients with advanced skin cancer. J. Dtsch. Derma. Gesell. 2023, 21, 1148–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinzerling, L.; De Toni, E.; Schett, G.; Hundorfean, G.; Zimmer, L. Checkpoint Inhibitors. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt Int. 2019, 116, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchtele, N.; Knaus, H.; Schellongowski, P. Side effects of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: What intensive care specialists need to know. Med. Klin. Intensiv. Notfmed. 2024, 119, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulf, H.; Volberg, C.; Morin, A. Symptomkontrolle in der Palliativmedizin (ohne Schmerztherapie). Anästhesiol. Intensiv. Notfallmed. Schmerzther. 2020, 55, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, A.E.; Waller, J.; Robb, K.; Wardle, J. Patient Delay in Presentation of Possible Cancer Symptoms: The Contribution of Knowledge and Attitudes in a Population Sample from the United Kingdom. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2010, 19, 2272–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.K.; Pope, C.; Botha, J.L. Patients’ help-seeking experiences and delay in cancer presentation: A qualitative synthesis. Lancet 2005, 366, 825–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.; Chapple, A.; Salisbury, H.; Corrie, P.; Ziebland, S. “It can’t be very important because it comes and goes”—patients’ accounts of intermittent symptoms preceding a pancreatic cancer diagnosis: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e004215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talib, T.L.; DeChant, P.; Kean, J.; Monahan, P.O.; Haggstrom, D.A.; Stout, M.E.; Kroenke, K. A qualitative study of patients’ perceptions of the utility of patient-reported outcome measures of symptoms in primary care clinics. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 3157–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierbach, E. Die Basis jeder Diagnose. Dtsch. Heilprakt.-Z. 2022, 17, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grüne, S. Anamnese und körperliche Untersuchung. Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 2015, 141, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrar, J.T.; Young, J.P.; LaMoreaux, L.; Werth, J.L.; Poole, M.R. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain 2001, 94, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruera, E.; Kuehn, N.; Miller, M.J.; Selmser, P.; Macmillan, K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): A simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J. Palliat. Care 1991, 7, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Bruera, E. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System 25 Years Later: Past, Present, and Future Developments. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2017, 53, 630–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiel, S.; Matthes, M.E.; Bertram, L.; Ostgathe, C.; Elsner, F.; Radbruch, L. Validierung der neuen Fassung des Minimalen Dokumentationssystems (MIDOS2) für Patienten in der Palliativmedizin: Deutsche Version der Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS). Schmerz 2010, 24, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elm, E.V.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007, 335, 806–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volberg, C.; Schönfeld, P.N.; Krönig, L.; Hertl, M.; Gschnell, M. Palliative care in dermatooncology—Current practice in German dermatooncological centers and specialist offices. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Gesell. 2024, 22, 1106–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel, J.S.; Greer, J.A.; Muzikansky, A.; Gallagher, E.R.; Admane, S.; Jackson, V.A.; Dahlin, C.M.; Blinderman, C.D.; Jacobsen, J.; Pirl, W.F.; et al. Early Palliative Care for Patients with Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörr, A.; Vogel, I.; Wittenbecher, F.; Westermann, J.; Thuss-Patience, P.; Ahn, J.; Pelzer, U.; Hardt, J.; Bullinger, L.; Flörcken, A. Effective symptom relief through continuous integration of palliative care in advanced renal cell carcinoma patients: Comprehensive measurement using the palliative care base assessment. Palliat. Care Soc. Pract. 2024, 18, 26323524241260424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Jawahri, A.; Greer, J.A.; Temel, J.S. Does palliative care improve outcomes for patients with incurable illness? A review of the evidence. J. Support. Oncol. 2011, 9, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhebungsbogen Hautkrebszentren. Stand 31.08.2022, Version J2. Available online: https://www.onkozert.de/organ/haut/ (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Fulton, J.J.; Newins, A.R.; Porter, L.S.; Ramos, K. Psychotherapy Targeting Depression and Anxiety for Use in Palliative Care: A Meta-Analysis. J. Palliat. Med. 2018, 21, 1024–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, N.; Roe, B.; Lowe, D.; Tandon, S.; Jones, T.; Brown, J.; Shaw, R.; Risk, J.; Rogers, S.N. Screening for distress using the distress thermometer and the University of Washington Quality of Life in post-treatment head and neck cancer survivors. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2017, 274, 2253–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Head, B.A.; Schapmire, T.J.; Keeney, C.E.; Deck, S.M.; Studts, J.L.; Hermann, C.P.; Scharfenberger, J.A.; Pfeifer, M.P. Use of the Distress Thermometer to discern clinically relevant quality of life differences in women with breast cancer. Qual. Life Res. 2012, 21, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volberg, C.; Urhahn, F.; Pedrosa Carrasco, A.J.; Morin, A.; Gschnell, M.; Huber, J.; Flegar, L.; Heers, H. End-of-Life Care Preferences of Patients with Advanced Urological Malignancies: An Explorative Survey Study at a Tertiary Referral Center. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuser, N.; Heers, H.; Gschnell, M.; Urhahn, F.; Schrade, S.; Volberg, C. Do We Have a Knowledge Gap with Our Patients?—On the Problems of Knowledge Transfer and the Implications at the End of Life. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betker, L.; Nagelschmidt, K.; Leppin, N.; Knorrenschild, J.R.; Volberg, C.; Berthold, D.; Sibelius, U.; Rief, W.; Barke, A.; Von Blanckenburg, P.; et al. The Difficulties in End-of-Life Discussions-Family Inventory (DEOLD-FI): Development and Initial Validation of a Self-Report Questionnaire in a Sample of Terminal Cancer Patients. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 62, e130–e138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagelschmidt, K.; Leppin, N.; Seifart, C.; Rief, W.; von Blanckenburg, P. Systematic mixed-method review of barriers to end-of-life communication in the family context. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2021, 11, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifart, C.; Koch, M.; Herzog, S.; Leppin, N.; Nagelschmidt, K.; Riera Knorrenschild, J.; Timmesfeld, N.; Denz, R.; Seifart, U.; Rief, W.; et al. Collaborative advance care planning in palliative care: A randomised controlled trial. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2024, spcare-2023-004175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|

| n = 457 (56.5%) | n = 352 (43.5%) | |

| Age (Mdn; R; Q1/Q3) * | 71; 82 (11–93); 61/71 years | 63; 85 (12–97); 53/75 years |

| Diagnose | ||

| Malignant melanoma | 272 (59.5%) | 247 (70.2%) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 76 (16.6%) | 24 (6.8%) |

| Basal cell carcinoma | 16 (3.5%) | 8 (2.3%) |

| Cutaneous sarcomas | 30 (6.6%) | 23 (6.5%) |

| Merkel cell carcinoma | 12 (2.6%) | 12 (3.4%) |

| Cutaneous lymphomas | 37 (8.1%) | 27 (7.7%) |

| Other | 14 (3.1%) | 11 (3.1%) |

| Ongoing tumour-specific therapy | ||

| None | 399 (87.3%) | 321 (91.2%) |

| Palliative | 40 (8.8%) | 21 (6.0%) |

| Adjuvant | 18 (3.9%) | 10 (2.8%) |

| Clinical Stage According to TNM Classification | |

|---|---|

| Malignant melanoma | |

| I | 185 (22.9%) |

| II | 126 (15.9%) |

| III | 138 (17.1%) |

| IV | 70 (8.7%) |

| n.a. | 0 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | |

| I | 36 (4.5%) |

| II | 36 (4.5%) |

| III | 17 (2.1%) |

| IV | 11 (1.4%) |

| n.a. | 0 |

| Basal cell carcinoma | |

| n.a. * | 24 (3.0%) |

| Cutaneous sarcomas | |

| I | 11 (1.4%) |

| II | 0 |

| III | 0 |

| IV | 0 |

| n.a. | 42 (5.2%) |

| Merkel cell carcinoma | |

| I | 9 (1.1%) |

| II | 4 (0.5%) |

| III | 9 (1.1%) |

| IV | 2 (0.2%) |

| n.a. | 0 |

| Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas | |

| I | 26 (3.2%) |

| II | 5 (0.6%) |

| III | 6 (0.7%) |

| IV | 4 (0.5%) |

| n.a. | 2 (0.2%) |

| Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas | |

| I | 9 (1.1%) |

| II | 0 |

| III | 0 |

| IV | 0 |

| n.a. | 12 (1.5%) |

| Other neoplasms | |

| I | 2 (0.2%) |

| II | 0 |

| III | 3 (0.4%) |

| IV | 7 (0.9%) |

| n.a. | 13 (1.6%) |

| Pain Relief | Dyspnoea Relief | Nausea Relief | Diarrhoea Relief | Obstipation Relief | Fatigue Relief | Pruritus Relief | Relief of Sleep Disorders | Relief of Anxiety | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5. percentile | −3 | −2 | −1 | −2 | −2 | −3 | −3 | −3 | −3 |

| 10. percentile | −2 | −1 | 0 | −0.3 | 0 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 |

| 25. percentile | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Median | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 75. percentile | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 90. percentile | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 95. percentile | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Range | 20 | 17 | 16 | 19 | 18 | 18 | 20 | 18 | 18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gschnell, M.; Thole, J.; Kroenig, L.; Arz, M.; Bender, A.; Hertl, M.; Volberg, C. Structured Symptom Assessment in Dermato-Oncology Patients—A Prospective Observational Study of the Usability of a Symptom Questionnaire. Cancers 2025, 17, 3763. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233763

Gschnell M, Thole J, Kroenig L, Arz M, Bender A, Hertl M, Volberg C. Structured Symptom Assessment in Dermato-Oncology Patients—A Prospective Observational Study of the Usability of a Symptom Questionnaire. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3763. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233763

Chicago/Turabian StyleGschnell, Martin, Jannis Thole, Lisa Kroenig, Marianne Arz, Armin Bender, Michael Hertl, and Christian Volberg. 2025. "Structured Symptom Assessment in Dermato-Oncology Patients—A Prospective Observational Study of the Usability of a Symptom Questionnaire" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3763. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233763

APA StyleGschnell, M., Thole, J., Kroenig, L., Arz, M., Bender, A., Hertl, M., & Volberg, C. (2025). Structured Symptom Assessment in Dermato-Oncology Patients—A Prospective Observational Study of the Usability of a Symptom Questionnaire. Cancers, 17(23), 3763. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233763