Pain Experience in Oncology: A Targeted Literature Review and Development of a Novel Patient-Centric Conceptual Model

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Data Sources, Search Strategy, and Quality Assessment

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

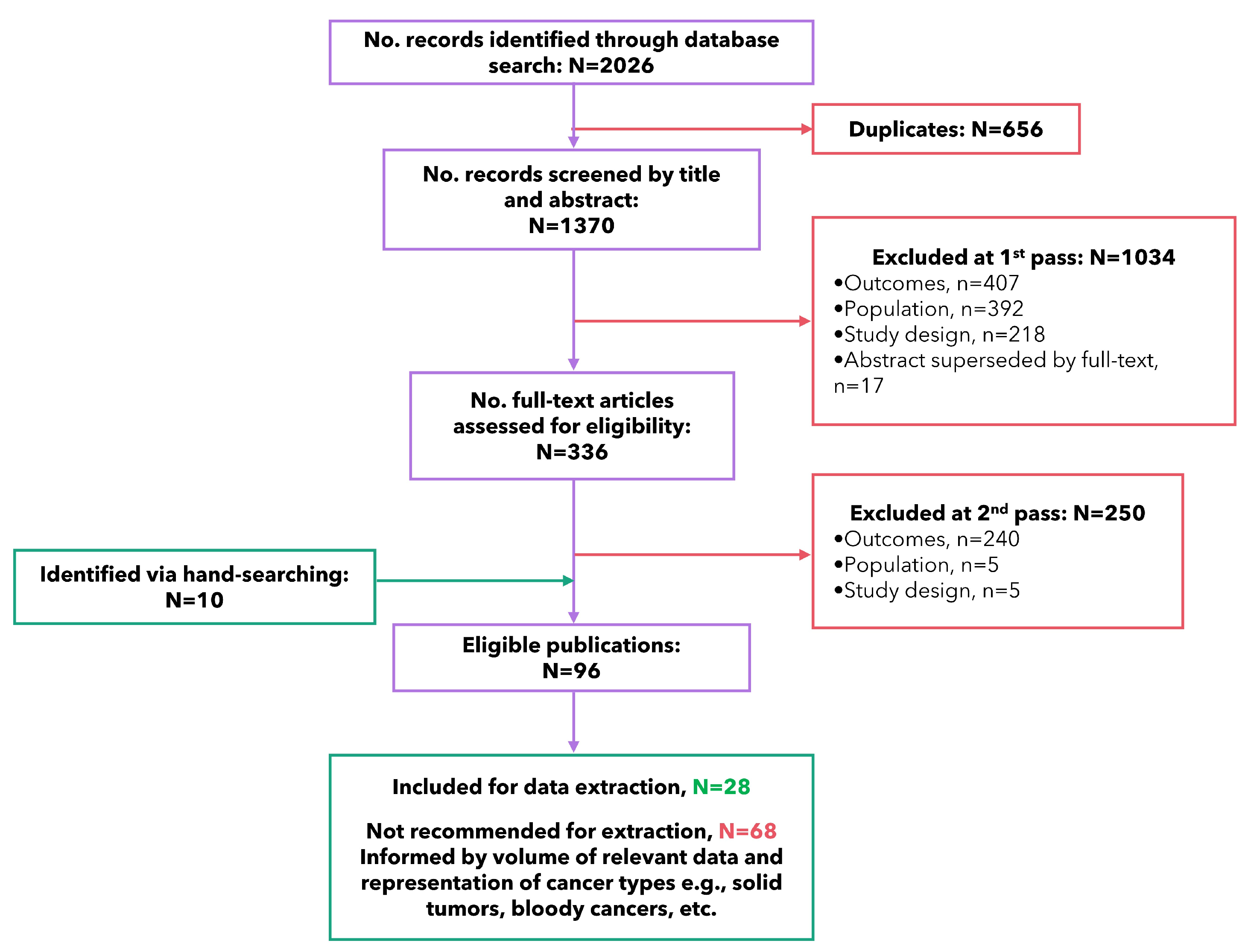

3.1. Study Selection

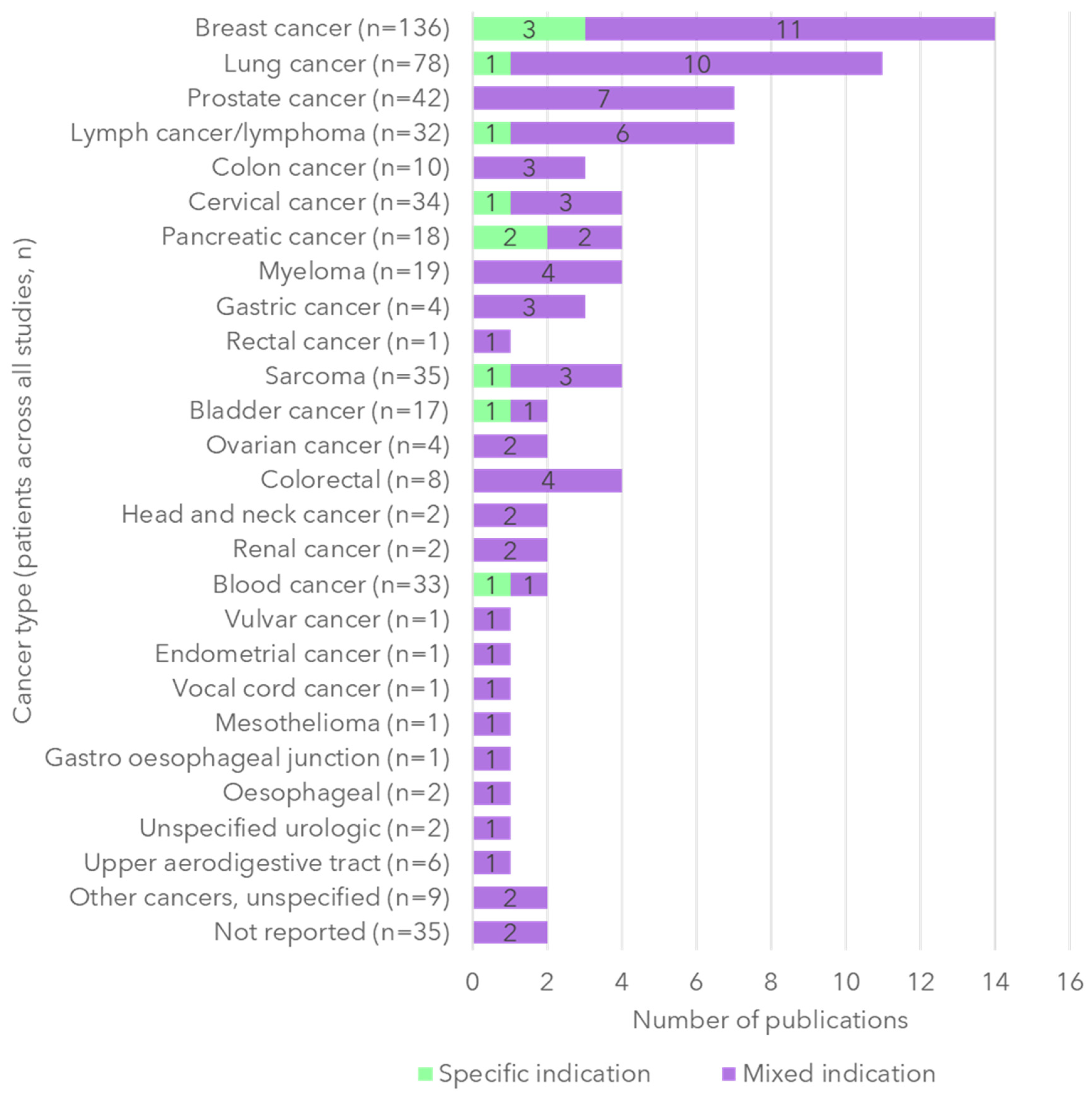

3.2. Study Characteristics

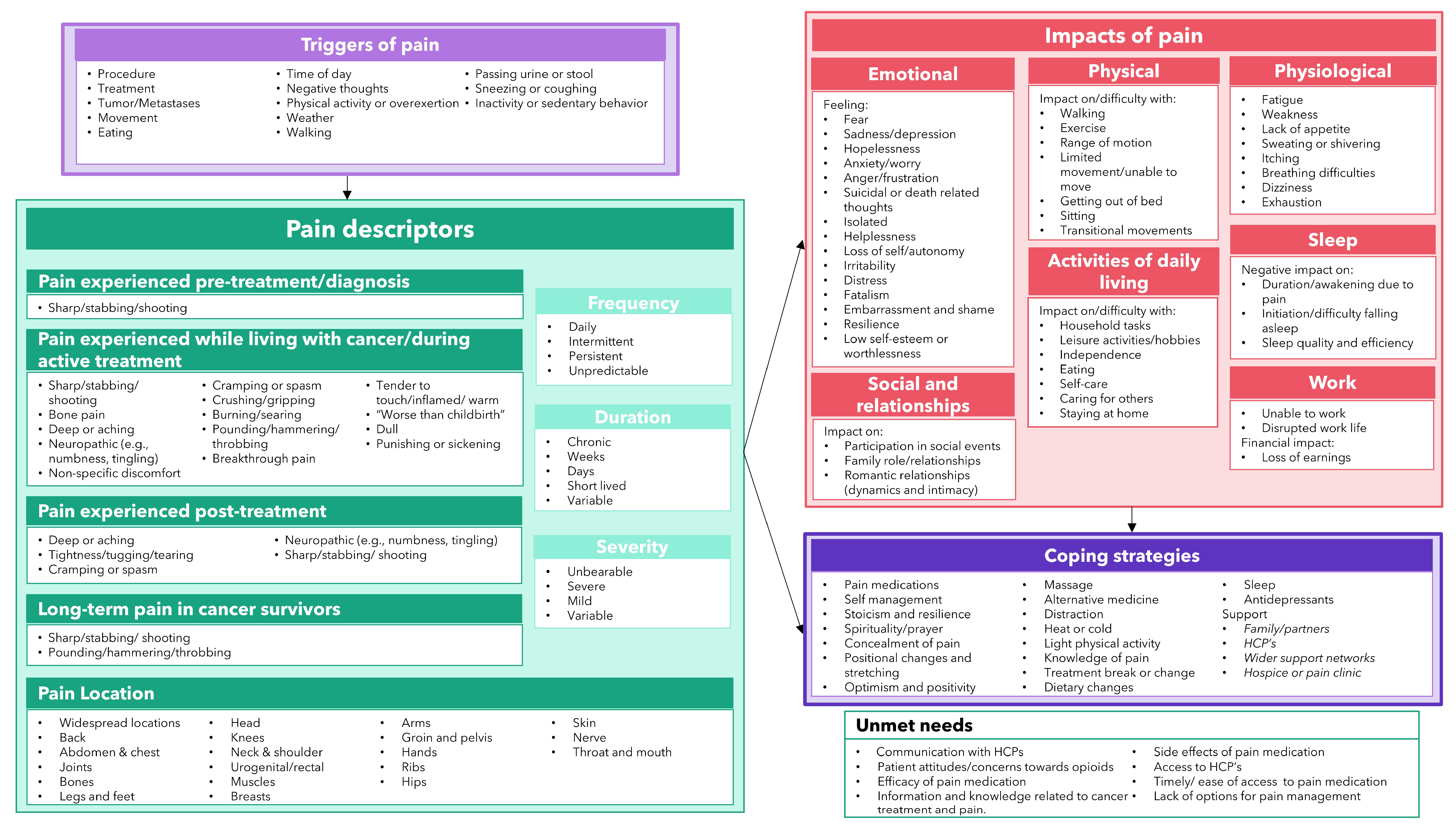

3.3. Pain Triggers

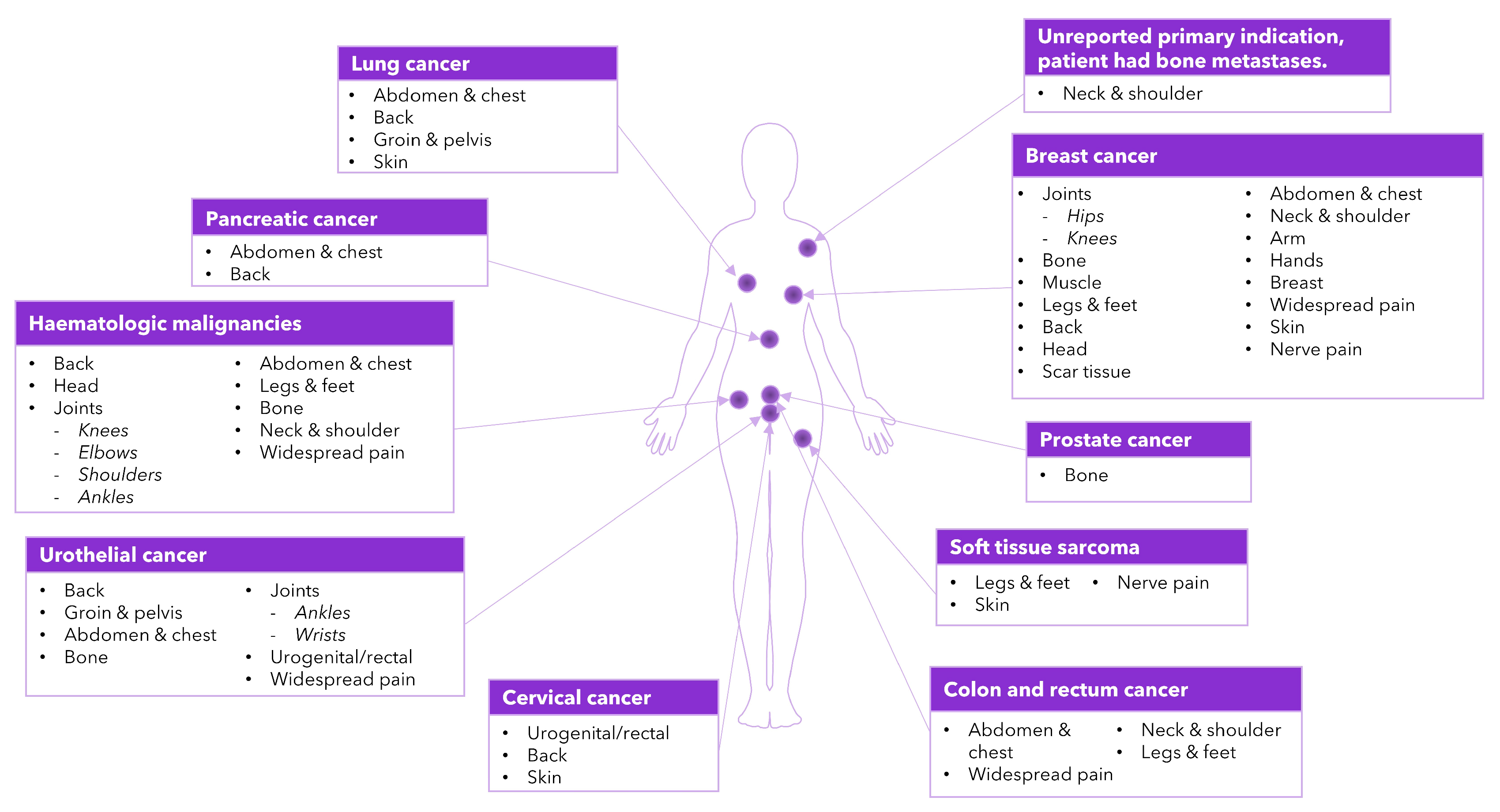

3.4. Pain Descriptors

3.5. Pain Impacts

3.5.1. Physiological

3.5.2. Physical

3.5.3. Emotional

3.5.4. Activities of Daily Living (ADLs)

3.5.5. Sleep

3.5.6. Social Functioning and Relationships

3.5.7. Work and Financial

3.6. Coping Strategies

3.7. Unmet Needs

3.8. Conceptual Model of the Patient Experience of Pain in Oncology

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jiang, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, Q.; Luo, Y.; Sidlow, R.; Han, X. Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain in cancer survivors in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 1224–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snijders, R.A.H.; Brom, L.; Theunissen, M.; van den Beuken-van Everdingen, M.H.J. Update on Prevalence of Pain in Patients with Cancer 2022: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2023, 15, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberto, A.; Greco, M.T.; Uggeri, S.; Cavuto, S.; Deandrea, S.; Corli, O.; Apolone, G. Living systematic review to assess the analgesic undertreatment in cancer patients. Pain Pract. 2022, 22, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.I.; Kaasa, S.; Barke, A.; Korwisi, B.; Rief, W.; Treede, R.-D. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: Chronic cancer-related pain. Pain 2019, 160, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinten, C.; Coens, C.; Mauer, M.; Comte, S.; Sprangers, M.A.G.; Cleeland, C.; Osoba, D.; Bjordal, K.; Bottomley, A. Baseline quality of life as a prognostic indicator of survival: A meta-analysis of individual patient data from EORTC clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paice, J.A.; Portenoy, R.; Lacchetti, C.; Campbell, T.; Cheville, A.; Citron, M.; Constine, L.S.; Cooper, A.; Glare, P.; Keefe, F.; et al. Management of Chronic Pain in Survivors of Adult Cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 3325–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ośmiałowska, E.; Misiąg, W.; Chabowski, M.; Jankowska-Polańska, B. Coping Strategies, Pain, and Quality of Life in Patients with Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, J.D.; Johnson, J.T.; Nilsen, M.L. Pain in Head and Neck Cancer Survivors: Prevalence, Predictors, and Quality-of-Life Impact. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 159, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Beuken-van Everdingen, M.H.J.; van Kuijk, S.M.J.; Janssen, D.J.A.; Joosten, E.A.J. Treatment of Pain in Cancer: Towards Personalised Medicine. Cancers 2018, 10, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestdagh, F.; Steyaert, A.; Lavand’homme, P. Cancer Pain Management: A Narrative Review of Current Concepts, Strategies, and Techniques. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 6838–6858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Patient-Focused Drug Development: Selecting, Developing, or Modifying Fit-for-Purpose Clinical Outcome Assessments. Guidance for Industry, Food and Drug Administration Staff, and Other Stakeholders; Draft Guidance; Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Restivo, L.; Dudoit, É.; Duffaud, F.; Salas, S.; Dany, L. “Fortunately I felt pain, or I would have thought I was on my way out”: Experiencing pain and negotiating analgesic treatment in the context of cancer. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2023, 41, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, L.; Elliott, E.; Voorhaar, M.; Ingelgård, A.; Griebsch, I.; Wong, B.; Mills, J.; Heinrich, P.; Cano, S. A Mixed-Methods Study to Better Measure Patient-Reported Pain and Fatigue in Soft Tissue Sarcoma. Oncol. Ther. 2023, 11, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Checklist. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-checklists/CASP-checklist-qualitative-2024.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Carmichael, C.; Collins, E.; Marshall, C.; Macey, J. Qualitative Content Analysis for Concept Elicitation (CACE) in Clinical Outcome Assessment Development. Value Health 2023, 26, S423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, R.; de Bruin, M.; Burton, C.D.; Bond, C.M.; Clausen, M.G.; Murchie, P. What are the current challenges of managing cancer pain and could digital technologies help? BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2018, 8, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allsop, M.J.; Taylor, S.; Bennett, M.I.; Bewick, B.M. Understanding patient requirements for technology systems that support pain management in palliative care services: A qualitative study. Health Inform. J. 2019, 25, 1105–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleyard, S.E.; Clarke, C. An interpretative phenomenological analysis of the experiences of older people self-managing cancer pain at home. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2018, 36, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benali, K.; Kebdani, T.; Hassouni, K.; El Kacemi, H.; El Majjaoui, S.; Benjaafar, N. Experiences of Women Receiving Multifraction High Dose-Rate Brachytherapy for Cervical Cancer: A Prospective Qualitative Study. J. Cancer Ther. 2022, 13, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, D.; Kelly, K.; de la Motte, A.; Toublan, F.; Pandya, B.J.; Shah, M.V.; LeBlanc, T.W. The experience of patients with acute myeloid leukemia in remission post-transplant. Leuk. Lymphoma 2023, 64, 1275–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekstedt, M.; Rustøen, T. Factors that hinder and facilitate cancer patients’ knowledge about pain management—A qualitative study. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2019, 57, 753–760.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englid, M.B.; Jirwe, M.; Conte, H. Perioperative Comfort and Discomfort: Transitioning From Epidural to Oral Pain Treatment After Pancreas Surgery: A Qualitative Study. J. PeriAnesthesia Nurs. 2023, 38, 414–420.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erol, O.; Unsar, S.; Yacan, L.; Pelin, M.; Kurt, S.; Erdogan, B. Pain experiences of patients with advanced cancer: A qualitative descriptive study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 33, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everaars, K.E.; Welbie, M.; Hummelink, S.; Tjin, E.P.; de Laat, E.H.; Ulrich, D.J. The impact of scars on health-related quality of life after breast surgery: A qualitative exploration. J. Cancer Surviv. 2021, 15, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassankhani, H.; Hajaghazadeh, M.; Orujlu, S. Patients’ Experiences of Cancer Pain: A Descriptive Qualitative Study. J. Palliat. Care 2023, 38, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, F.S.; Line Itty, T.; Arbing, R.H.; Samuel-Nakamura, C. A window into pain: American Indian cancer survivors’ drawings. Front. Pain Res. 2022, 3, 1031347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koulouris, A. The Epidemiology of Abdominal Pain in Inoperable Pancreatic Cancer and the Potential Role of Early Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Coeliac Plexus Neurolysis. Ph.D. Thesis, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Gao, L.-L.; Dai, Y.-L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.-X.; Luo, X.-J.; Chai, X.-M.; Mu, G.-X.; Liang, X.-Y.; Zhang, X. Breakthrough pain: A qualitative study of patients with advanced cancer in Northwest China. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2018, 19, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maly, A.; Singh, N.; Vallerand, A.H. Experiences of urban African Americans with cancer pain. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2018, 19, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, S.; Shah, S.N.; Hepp, Z.; Harris, N.; Morgans, A.K. Qualitative analysis of pain in patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Bladder Cancer 2022, 8, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabulsi, N.A.; Nazari, J.L.; Lee, T.A.; Patel, P.R.; Sweiss, K.I.; Le, T.; Sharp, L.K. Perceptions of prescription opioids among marginalized patients with hematologic malignancies in the context of the opioid epidemic: A qualitative study. J. Cancer Surviv. 2023, 18, 1285–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Regan, A.; Fish, L.J.; Makarushka, C.; Somers, T.; Fitzgerald Jones, K.; Merlin, J.S.; Dinan, M.; Oeffinger, K.; Check, D. Managing Chronic Pain in Cancer Survivorship: Communication Challenges and Opportunities as Described by Cancer Survivors. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2023, 41, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, K.L.; Clark, V.L.P.; Rabow, M.W.; Paul, S.M.; Miaskowski, C. The experience of complex pain dynamics in oncology outpatients: A longitudinal qualitative analysis. Cancer Nurs. 2021, 44, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.D.; Manning, J.; Nielsen, M.; Hayes, S.C.; Plinsinga, M.L.; Coppieters, M.W. Exploring women’s experiences with persistent pain and pain management following breast cancer treatment: A qualitative study. Front. Pain Res. 2023, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestergaard, K.; Vissing, M.; Gehl, J.; Lindhardt, C.L. Qualitative investigation of experience and quality of life in patients treated with calcium electroporation for cutaneous metastases. Cancers 2023, 15, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, E.A.; Chabria, R.; Vranceanu, A.M.; Park, E.R.; Post, K.; Peppercorn, J.; Temel, J.S.; Greer, J.A.; Jacobs, J.M. Understanding pain related to adjuvant endocrine therapy after breast cancer: A qualitative report. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2022, 31, e13723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Yu, H.; Dai, W.; Xu, W.; Yu, Q.; Pu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liao, J.; Li, Q.; Shi, Q. Discrepancy in the perception of symptoms among patients and healthcare providers after lung cancer surgery. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whisenant, M.S.; Srour, S.A.; Williams, L.A.; Subbiah, I.; Griffin, D.; Ponce, D.; Kebriaei, P.; Neelapu, S.S.; Shpall, E.; Ahmed, S. The unique symptom burden of patients receiving CAR T-cell therapy. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2021, 37, 151216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Cheng, Q.; Ou, M.; Li, S.; Xie, C.; Chen, Y. Pain acceptance in cancer patients with chronic pain in Hunan, China: A qualitative study. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2019, 6, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, K.A.; Quest, T.E.; Vena, C.; Sterk, C.E. Living with symptoms: A qualitative study of black adults with advanced cancer living in poverty. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2018, 19, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, K.A.; Rosa, W.E.; Belcher, S.M.; Lee, S.M.; Lee, H.; Bruner, D.W.; Meghani, S.H. A Qualitative Study of the Pain Experience of Black Individuals With Cancer Taking Long-Acting Opioids. Cancer Nurs. 2023, 47, E73–E83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, C.F.; Aaronson, N.K.; Choucair, A.K.; Elliott, T.E.; Greenhalgh, J.; Halyard, M.Y.; Hess, R.; Miller, D.M.; Reeve, B.B.; Santana, M. Implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice: A review of the options and considerations. Qual. Life Res. 2012, 21, 1305–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Core Patient-Reported Outcomes in Cancer Clinical Trials: Guidance for Industry; Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin, R.H.; Turk, D.C.; Farrar, J.T.; Haythornthwaite, J.A.; Jensen, M.P.; Katz, N.P.; Kerns, R.D.; Stucki, G.; Allen, R.R.; Bellamy, N. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain 2005, 113, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Food and Drug Administration. Development of Non-Opioid Analgesics for Acute Pain: Guidance for Industry (Draft). Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/156063/download (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- Araujo, D.V.; Soler, J.A.; Cordeiro de Lima, V.C. Patient-centered trials in oncology: Time for a change. Med 2022, 3, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paller, C.J.; Campbell, C.M.; Edwards, R.R.; Dobs, A.S. Sex-based differences in pain perception and treatment. Pain Med. 2009, 10, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Criteria | Include | Exclude |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

|

|

| Intervention/ Comparator |

|

|

| Study design |

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Publication language |

|

|

| Date of publication |

|

|

| Study | Sample Size, n | Cancer Type(s) | Females, n | Age, Years (Mean [Range]) | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adam, 2018 [18] | 14 | Mixed population (breast, n = 1; lymphoma, n = 1; renal/pancreatic, n = 1; prostate, n = 2; colorectal, n = 2; ovarian, n = 1; lung, n = 3; gastro-esophageal junction, n = 1; esophagus, n = 2) | 4 | Not reported [56–76] | GB |

| Allsop, 2019 [19] | 13 | Mixed population (prostate, n = 7; breast, n = 3; head and neck, n = 1; colon, n = 1; mesothelioma, n = 1) | 5 | 67.77 [50–83] | GB |

| Appleyard, 2018 [20] | 8 | Mixed population (myeloma, n = 3; prostate, n = 3; colorectal, n = 1; bladder, n = 1) | 1 | 76.38 [72–85] | GB |

| Barrett, 2023 [13] | 28 | Soft tissue sarcoma | 22 | 43 [22–79] | Not reported |

| Benali, 2022 [21] | 31 | Cervical | 31 | Not reported [27–70] | Morocco |

| Cella, 2023 [22] | 30 | Acute myeloid leukemia | 17 | Not reported [28–72] | US, Germany |

| Ekstedt, 2019 [23] | 20 | Mixed population (breast, n = 7; prostate, n = 9; other [not specified], n = 4) | 8 | Not reported [45–83] | Norway |

| Englid, 2023 [24] | 12 | Pancreatic | 5 | 67 [56–74] | Sweden |

| Erol, 2018 [25] | 16 | Mixed population (lung, n = 8; colon, n = 6; gastric: n = 2) | 3 | 62.75 [not reported] | Turkey |

| Everaars, 2021 [26] | 26 | Breast | 26 | 56.9 [32–77] | The Netherlands |

| Hassankhani, 2023 [27] | 17 | Mixed population (breast, n = 5; colon, n = 3; lymphoma, n = 3; blood, n = 3; lung, n = 1; gastric, n = 1; vulvar, n = 1) | 12 | 39.4 [21–55] | Iran |

| Hodge, 2022 [28] | 17 | Not reported | 16 | Not reported | US |

| Koulouris, 2021 [29] | 4 | Pancreatic | 2 | Not reported [61–82] | GB |

| Liu, 2018 [30] | 9 | Mixed population (lung, n = 1; breast, n = 2; pancreatic, n = 1; gastric, n = 1; cervical, n = 1; prostate, n = 1; rectal, n = 1; lymph, n = 1) | 4 | Not reported [37–76] | China |

| Maly, 2018 [31] | 18 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | US |

| Martin, 2022 [32] | 16 | Bladder | 8 | 53.8 [46–64] | US |

| Nabulsi, 2023 [33] | 20 | Mixed population (multiple myeloma, n = 10; leukemia, n = 5; lymphoma, n = 4; myelofibrosis, n = 1) | 12 | Not reported [not reported] | US |

| O’Regan, 2022 [34] | 13 | Mixed population (breast, n = 9; lung, n = 3; head and neck, n = 1) | 10 | 57 [40–81] | US |

| Restivo, 2023 [12] | 16 | Mixed population (upper aerodigestive tract, n = 6; sarcoma, n = 5; gynecologic, n = 3; urologic, n = 2) | 8 | 56.18 [22–82] | France |

| Schumacher, 2021 [35] | 42 | Mixed population (prostate, n = 17; breast, n = 14; lung, n = 6; other unspecified, n = 5) | 17 | 64.0 [not reported] | US |

| Smith, 2023 [36] | 14 | Breast | 14 | 55.8 [not reported] | Australia |

| Vestergaard, 2023 [37] | 7 | Mixed population (breast, n = 3; lung, n = 3; endometrial, n = 1) | 6 | 66.43 [not reported] | Denmark |

| Walsh, 2022 [38] | 30 | Breast | 30 | 55.13 [27–76] | US |

| Wei, 2022 [39] | 39 | Lung | 24 | Not reported [42–82] | China |

| Whisenant, 2021 [40] | 21 | B-Cell lymphoid malignancies | 5 | 61.4 [not reported] | US |

| Xu, 2019 [41] | 12 | Mixed population (lung, n = 4; breast, n = 3; colorectal cancer, n = 2; myeloma, n = 1; liposarcoma, n = 1; non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, n = 1) | 6 | Not reported | China |

| Yeager, 2018 [42] | 27 | Mixed population (breast, n = 9; lung, n = 8; prostate, n = 3; ovarian, n = 3; cervical, n = 1; leiomyosarcoma, n = 1; renal cell, n = 1; vocal cord, n = 1) | 18 | 57 [30–79] | US |

| Yeager, 2023 [43] | 14 | Mixed population (multiple myeloma, n = 5; colorectal, n = 3; lung, n = 2; breast, n = 2; cervical, n = 1; lymphoma, n = 1) | 9 | Not reported [not reported] | US |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carmichael, C.; Van Tomme, S.; Miller, J.; Burns, D.; Gousset, C.; Kitchen, H.; Makin, H.; Aldhouse, N.V.J.; Cordero, P. Pain Experience in Oncology: A Targeted Literature Review and Development of a Novel Patient-Centric Conceptual Model. Cancers 2025, 17, 3760. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233760

Carmichael C, Van Tomme S, Miller J, Burns D, Gousset C, Kitchen H, Makin H, Aldhouse NVJ, Cordero P. Pain Experience in Oncology: A Targeted Literature Review and Development of a Novel Patient-Centric Conceptual Model. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3760. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233760

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarmichael, Chloe, Sophie Van Tomme, Jordan Miller, Danielle Burns, Cecile Gousset, Helen Kitchen, Harriet Makin, Natalie V. J. Aldhouse, and Paul Cordero. 2025. "Pain Experience in Oncology: A Targeted Literature Review and Development of a Novel Patient-Centric Conceptual Model" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3760. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233760

APA StyleCarmichael, C., Van Tomme, S., Miller, J., Burns, D., Gousset, C., Kitchen, H., Makin, H., Aldhouse, N. V. J., & Cordero, P. (2025). Pain Experience in Oncology: A Targeted Literature Review and Development of a Novel Patient-Centric Conceptual Model. Cancers, 17(23), 3760. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233760