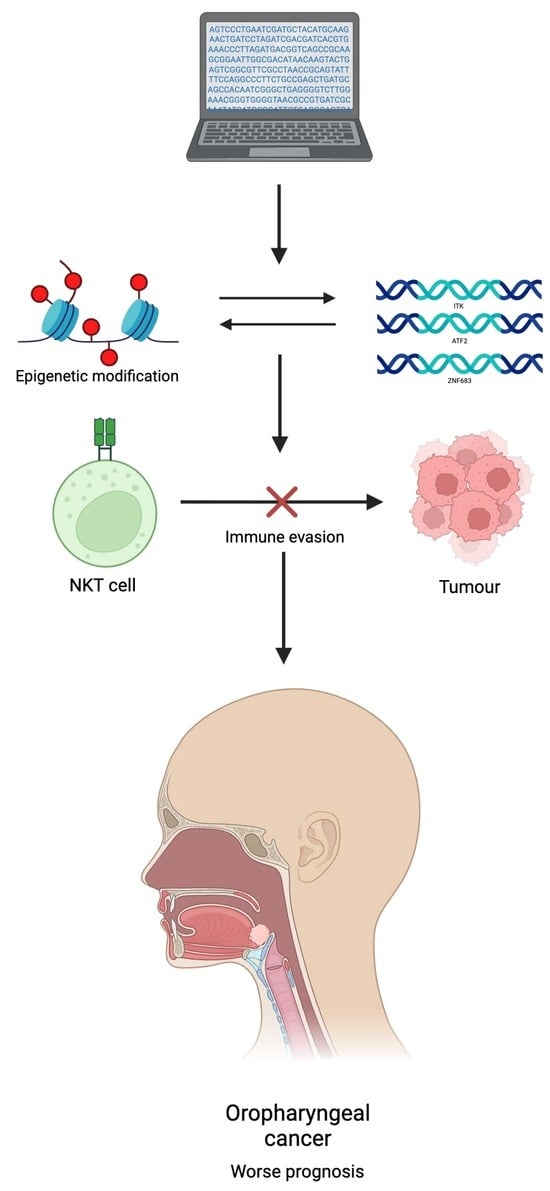

Epigenetic Regulation of NKT-Cell-Related Gene Signatures and Prognostic Implications in Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Transcriptomic Analysis of Immune-Related Gene Sets

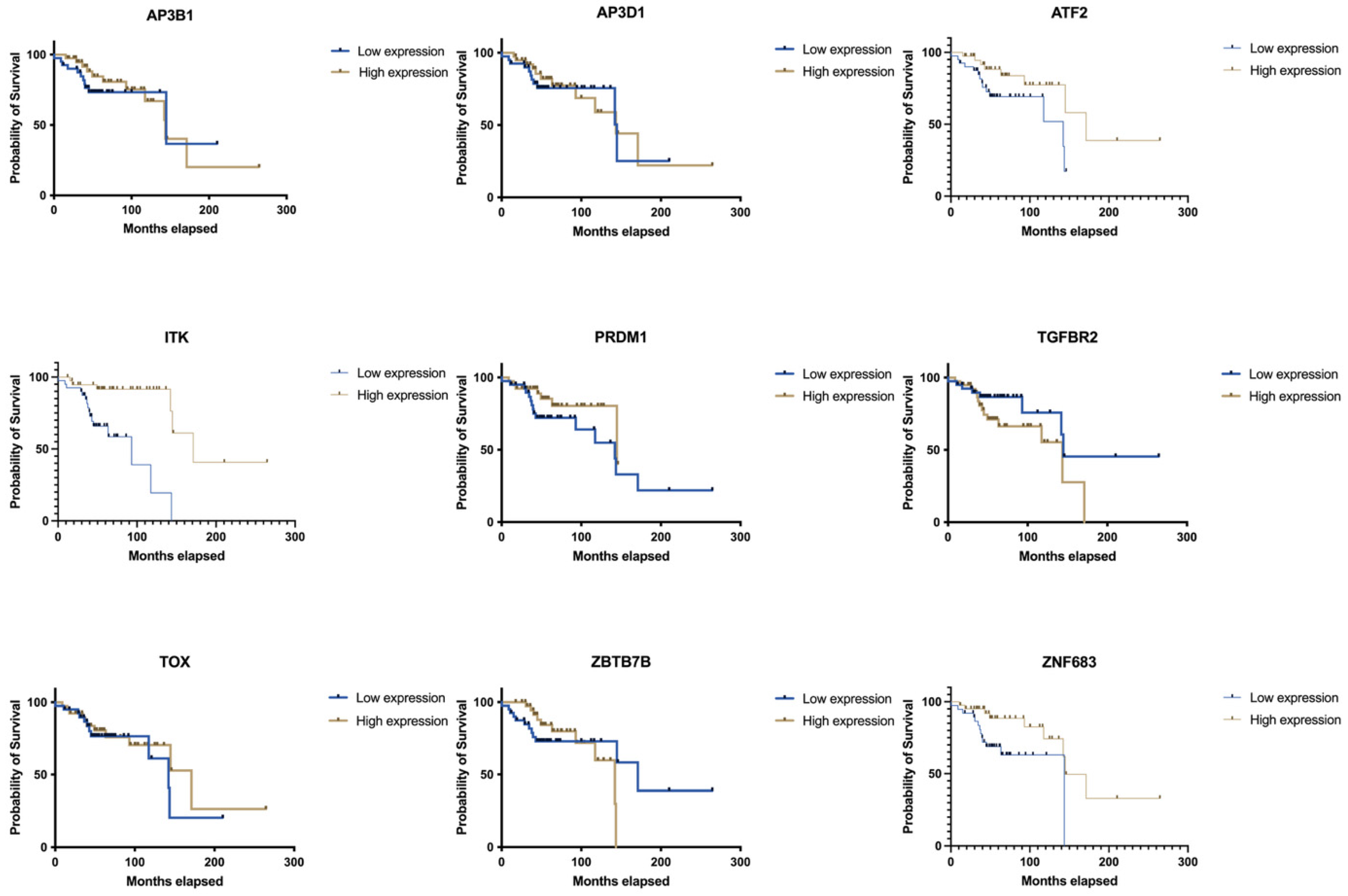

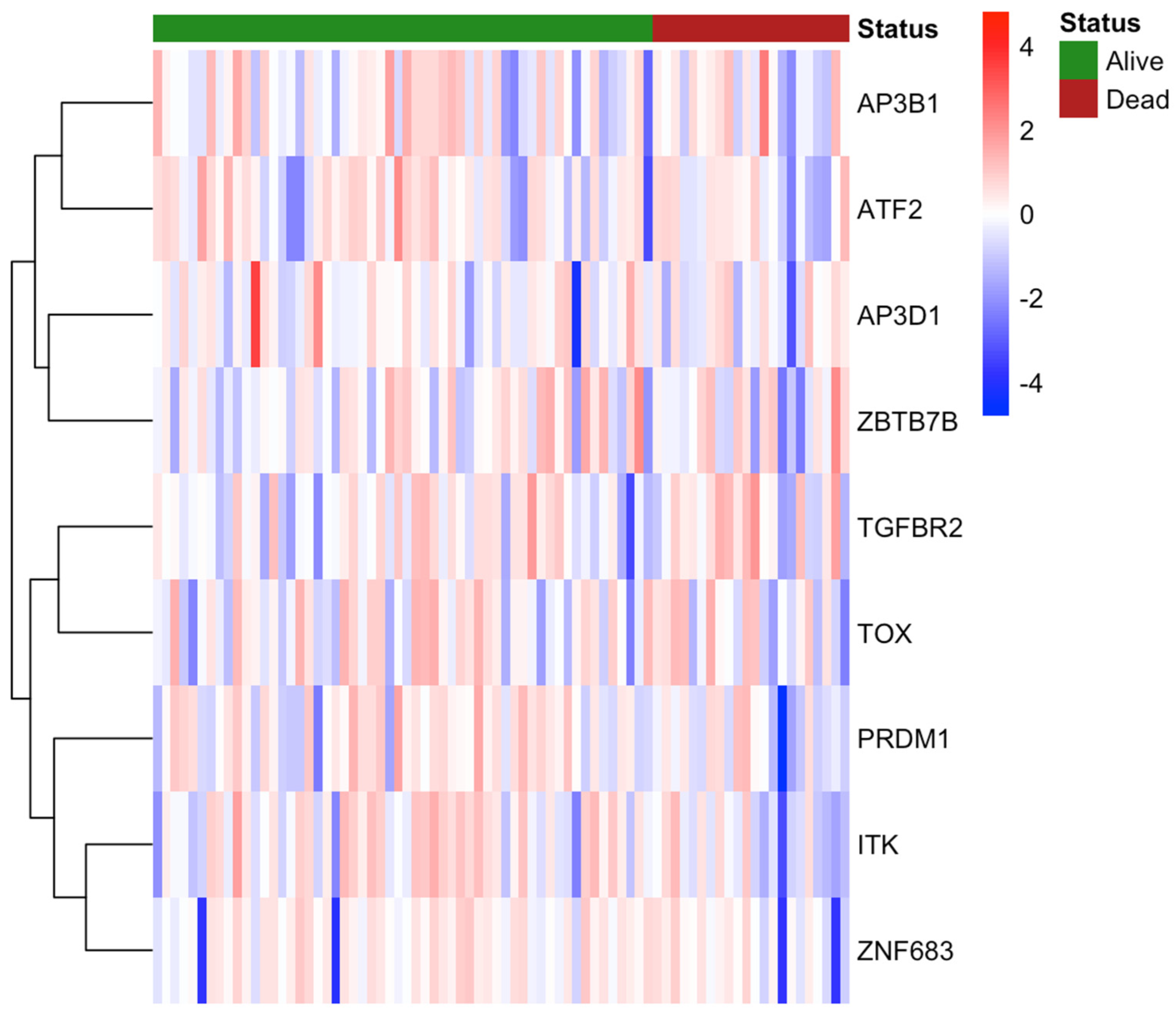

3.2. Clinical Data and NKT Cell Differentiation

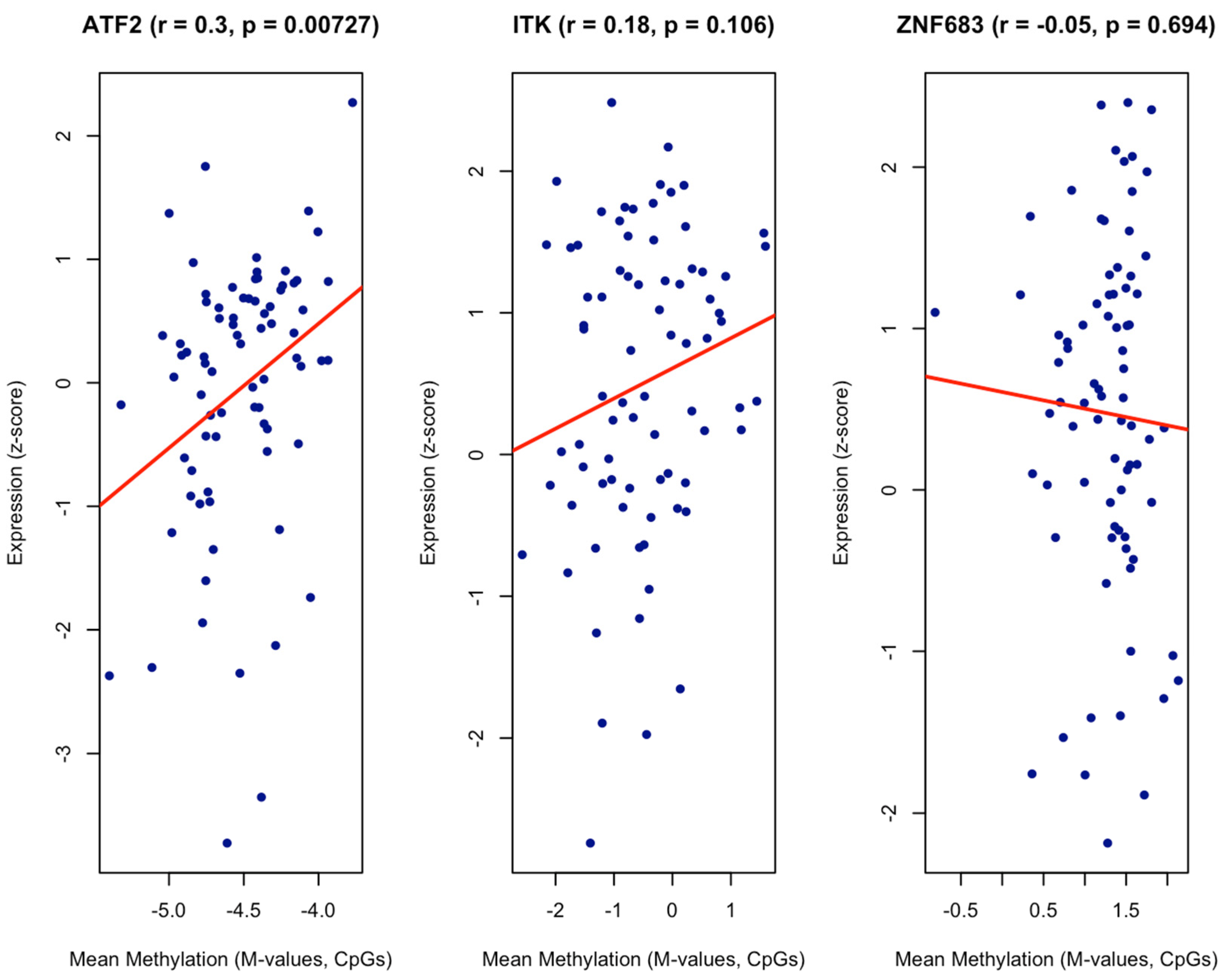

3.3. Gene Expression and Methylation

3.4. Macrophage Activation and Clinical Data

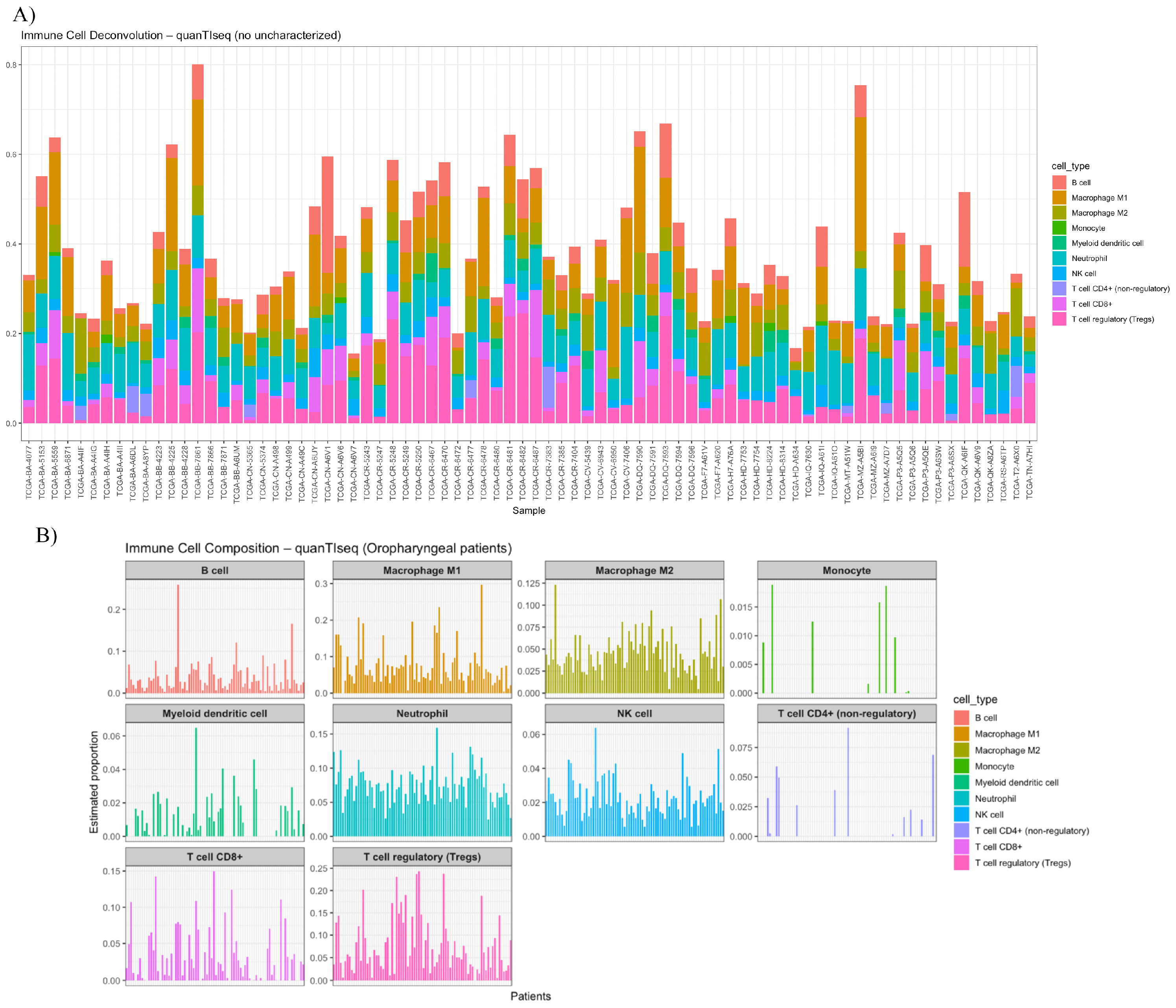

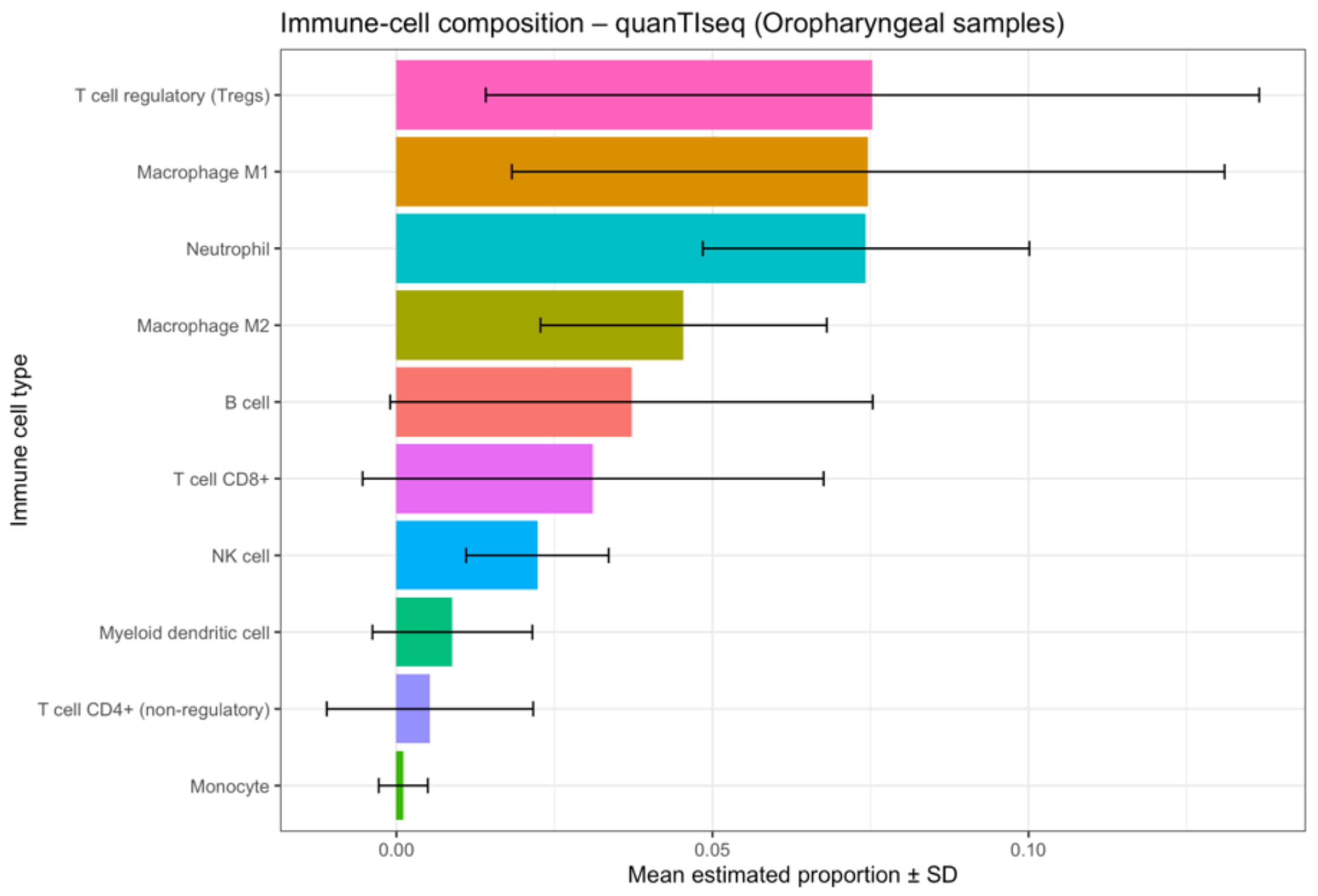

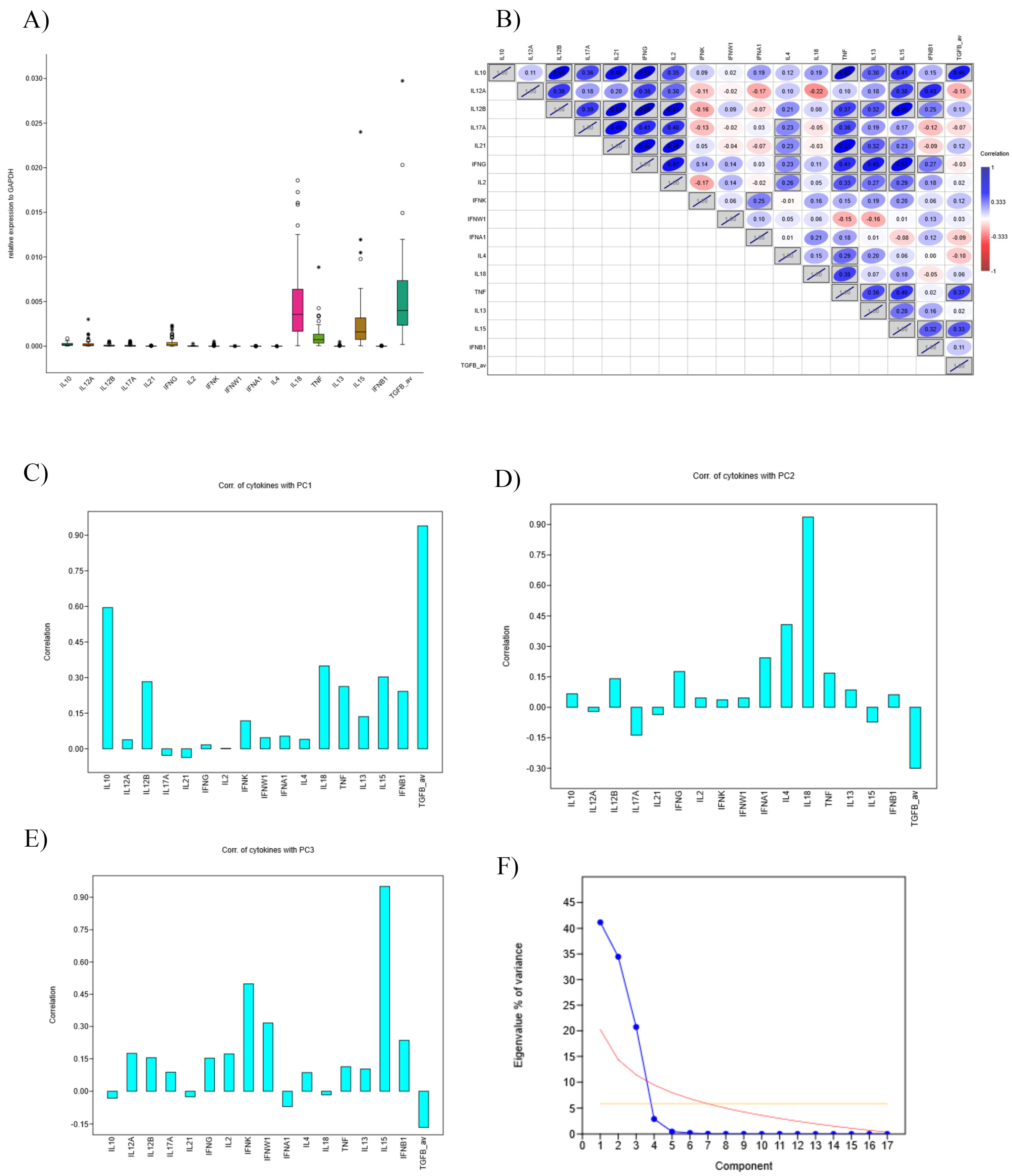

3.5. Deconvolution and Interleukin Expression

3.6. KEGG Pathway Enrichment and Gene–Pathway Network Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Term |

| AJCC | American Joint Committee on Cancer |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| ATF2 | Activating Transcription Factor 2 |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| cloglog | Complementary Log-Log |

| CRE | cAMP Response Element |

| GEO | Gene Expression Omnibus |

| GOBP | Gene Ontology Biological Process |

| H2B | Histone 2B |

| HNC | Head and Neck Cancer |

| HNSCC | Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| HPV | Human Papillomavirus |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| IFN | Interferon |

| IL | Interleukin |

| ITK | IL2-Inducible T-cell Kinase |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| KM | Kaplan–Meier |

| LAT | Linker for Activation of T cells |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| MHC | Major Histocompatibility Complex |

| MSigDB | Molecular Signatures Database |

| NK | Natural Killer |

| NKT | Natural Killer T (cell) |

| OPSCC | Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| OS | Overall Survival |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PD-1 | Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed Death-Ligand 1 |

| RNA-Seq | RNA Sequencing |

| RSEM | RNA-Seq by Expectation-Maximisation |

| ssGSEA | Single-Sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| TCR | T-cell Receptor |

| TGFβ | Transforming Growth Factor Beta |

| TGFBR2 | Transforming Growth Factor Beta Receptor 2 |

| Th17 | T Helper 17 (cell) |

| TIM | Tumour Immune Microenvironment |

| TMB | Tumour Mutational Burden |

| TNFα | Tumour Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| TME | Tumour Microenvironment |

| Trm | Tissue-Resident Memory (T cell) |

| Treg | Regulatory T cell |

| WAS | Wiskott–Aldrich Syndrome protein |

| ZNF683 | Zinc Finger Protein 683 (Hobit) |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaturvedi, A.K. Epidemiology and Clinical Aspects of HPV in Head and Neck Cancers. Head Neck Pathol. 2012, 6, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maschio, F.; Lejuste, P.; Ilankovan, V. Evolution in the Management of Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Systematic Review of Outcomes over the Last 25 Years. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 57, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaturvedi, A.K.; Engels, E.A.; Pfeiffer, R.M.; Hernandez, B.Y.; Xiao, W.; Kim, E.; Jiang, B.; Goodman, M.T.; Sibug-Saber, M.; Cozen, W.; et al. Human Papillomavirus and Rising Oropharyngeal Cancer Incidence in the United States. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 4294–4301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maluf, F.V.; Andricopulo, A.D.; Oliva, G.; Guido, R.V. A Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening Approach for the Discovery of Trypanosoma cruzi GAPDH Inhibitors. Future Med. Chem. 2013, 5, 2019–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.B.; Greene, F.L.; Edge, S.B.; Compton, C.C.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Brookland, R.K.; Meyer, L.; Gress, D.M.; Byrd, D.R.; Winchester, D.P. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to Build a Bridge from a Population-based to a More “Personalized” Approach to Cancer Staging. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardoll, D.M. The Blockade of Immune Checkpoints in Cancer Immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillison, M.L.; Blumenschein, G.; Fayette, J.; Guigay, J.; Colevas, A.D.; Licitra, L.; Harrington, K.J.; Kasper, S.; Vokes, E.E.; Even, C.; et al. CheckMate 141: 1-Year Update and Subgroup Analysis of Nivolumab as First-Line Therapy in Patients with Recurrent/Metastatic Head and Neck Cancer. Oncologist 2018, 23, 1079–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiwert, T.Y.; Burtness, B.; Mehra, R.; Weiss, J.; Berger, R.; Eder, J.P.; Heath, K.; McClanahan, T.; Lunceford, J.; Gause, C.; et al. Safety and Clinical Activity of Pembrolizumab for Treatment of Recurrent or Metastatic Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck (KEYNOTE-012): An Open-Label, Multicentre, Phase 1b Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.E.W.; Le Tourneau, C.; Licitra, L.; Ahn, M.-J.; Soria, A.; Machiels, J.-P.; Mach, N.; Mehra, R.; Burtness, B.; Zhang, P.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus methotrexate, docetaxel, or cetuximab for recurrent or metastatic head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-040): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 2019, 393, 156–167, Erratum in Lancet 2019, 393, 132. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33261-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristescu, R.; Mogg, R.; Ayers, M.; Albright, A.; Murphy, E.; Yearley, J.; Sher, X.; Liu, X.Q.; Lu, H.; Nebozhyn, M.; et al. Pan-tumor genomic biomarkers for PD-1 checkpoint blockade-based immunotherapy. Science 2018, 362, eaar3593, Erratum in Science 2019, 363, eaax1384. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, E.; Wood, O.; Ottensmeier, C.; King, E.; Thomas, G.; Elliott, T.; James, E. Differences in ERAP1 Allo-type Function Correlate with HPV Epitope Processing and Level of Tumour Infiltration with CD8+ T Cells in HPV-Positive OPSCC. Mol. Immunol. 2022, 150, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, M.; Lunceford, J.; Nebozhyn, M.; Murphy, E.; Loboda, A.; Kaufman, D.R.; Albright, A.; Cheng, J.D.; Kang, S.P.; Shankaran, V.; et al. IFN-γ-Related MRNA Profile Predicts Clinical Response to PD-1 Blockade. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 2930–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Kuang, M.; Chen, H.; Luo, Y.; You, K.; Zhang, B.; Liu, Y. Single-Sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis Reveals the Clinical Implications of Immune-Related Genes in Ovarian Cancer. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1426274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Lv, X.; Li, Y.; Gao, X.; Ma, Z.; Fu, X.; Li, Y. Integrated Machine Learning and Single-Sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis Identifies a TGF-Beta Signaling Pathway Derived Score in Headneck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Oncol. 2022, 2022, 3140263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbie, D.A.; Tamayo, P.; Boehm, J.S.; Kim, S.Y.; Moody, S.E.; Dunn, I.F.; Schinzel, A.C.; Sandy, P.; Meylan, E.; Scholl, C.; et al. Systematic RNA Interference Reveals That Oncogenic KRAS-Driven Cancers Require TBK1. Nature 2009, 462, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.H. Biostatistics 104: Correlational Analysis. Singap. Med. J. 2003, 44, 614–619. [Google Scholar]

- Soares-Lima, S.C.; Mehanna, H.; Camuzi, D.; de Souza-Santos, P.T.; de Simão, T.A.; Nicolau-Neto, P.; de Al-meida Lopes, M.S.; Cuenin, C.; Talukdar, F.R.; Batis, N.; et al. Upper Aerodigestive Tract Squamous Cell Carcinomas Show Distinct Overall DNA Methylation Profiles and Different Molecular Mechanisms behind WNT Signaling Disruption. Cancers 2021, 13, 3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, T.; Matsusaka, K.; Misawa, K.; Ota, S.; Takane, K.; Fukuyo, M.; Rahmutulla, B.; Shinohara, K.I.; Kunii, N.; Sakurai, D.; et al. Frequent Promoter Hypermethylation Associated with Human Papillomavirus Infection in Pharyngeal Cancer. Cancer Lett. 2017, 407, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechien, J.R.; Seminerio, I.; Descamps, G.; Mat, Q.; Mouawad, F.; Hans, S.; Julieron, M.; Dequanter, D.; Vanderhaegen, T.; Journe, F.; et al. Impact of HPV Infection on the Immune System in Oropharyngeal and Non-Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. Cells 2019, 8, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Arooj, S.; Wang, H. NK Cell-Based Immune Checkpoint Inhibition. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, A.N.; Tian, G.; Metelitsa, L.S. Natural Killer T Cells and Other Innate-like T Lymphocytes as Emerging Platforms for Allogeneic Cancer Cell Therapy. Blood 2023, 141, 869–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terabe, M.; Berzofsky, J.A. The Role of NKT Cells in Tumor Immunity. Adv. Cancer Res. 2008, 101, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumsteg, Z.S.; Luu, M.; Rosenberg, P.S.; Elrod, J.K.; Bray, F.; Vaccarella, S.; Gay, C.; Lu, D.J.; Chen, M.M.; Chaturvedi, A.K.; et al. Global Epidemiologic Patterns of Oropharyngeal Cancer Incidence Trends. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2023, 115, 1544–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhodapkar, M.V.; Geller, M.D.; Chang, D.H.; Shimizu, K.; Fujii, S.I.; Dhodapkar, K.M.; Krasovsky, J. A Reversible Defect in Natural Killer T Cell Function Characterizes the Progression of Premalignant to Malignant Multiple Myeloma. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 197, 1667–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molling, J.W.; Langius, J.A.E.; Langendijk, J.A.; Leemans, C.R.; Bontkes, H.J.; Van Der Vliet, H.J.J.; Von Blomberg, B.M.E.; Scheper, R.J.; Van Den Eertwegh, A.J.M. Low Levels of Circulating Invariant Natural Killer T Cells Predict Poor Clinical Outcome in Patients with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 862–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, S.; Wittekindt, C.; Reuschenbach, M.; Hennig, B.; Thevarajah, M.; Würdemann, N.; Prigge, E.S.; Von Knebel Doeberitz, M.; Dreyer, T.; Gattenlöhner, S.; et al. CD56-Positive Lymphocyte Infiltration in Relation to Human Papillomavirus Association and Prognostic Significance in Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 138, 2263–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangl, S.; Tontcheva, N.; Sievert, W.; Shevtsov, M.; Niu, M.; Schmid, T.E.; Pigorsch, S.; Combs, S.E.; Haller, B.; Balermpas, P.; et al. Heat Shock Protein 70 and Tumor-infiltrating NK Cells as Prognostic Indicators for Patients with Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck after Radiochemotherapy: A Multicentre Retrospective Study of the German Cancer Consortium Radiation Oncology Group (DKTK-ROG). Int. J. Cancer 2017, 142, 1911–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawasaki, H.; Schiltz, L.; Chiu, R.; Itakura, K.; Taira, K.; Nakatani, Y.; Yokoyama, K.K. ATF-2 Has Intrinsic Histone Acetyltransferase Activity Which Is Modulated by Phosphorylation. Nature 2000, 405, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffey, D.; Dolgilevich, S.; Razzouk, S.; Li, L.; Green, R.; Gorti, G.K. Activating Transcription Factor-2 (ATF2) in Survival Mechanisms in Head and Neck Carcinoma Cells. Head Neck 2010, 33, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Maekawa, T.; Shinagawa, T.; Sano, Y.; Sakuma, T.; Nomura, S.; Nagasaki, K.; Miki, Y.; Saito-Ohara, F.; Inazawa, J.; Kohno, T.; et al. Reduced Levels of ATF-2 Predispose Mice to Mammary Tumors. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 27, 1730–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Wu, X.; Liu, N.; Li, X.; Meng, F.; Song, S. Silencing of ATF2 Inhibits Growth of Pancreatic Cancer Cells and Enhances Sensitivity to Chemotherapy. Cell Biol. Int. 2017, 41, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, S.; Mizushima, T.; Ide, H.; Jiang, G.; Goto, T.; Nagata, Y.; Netto, G.J.; Miyamoto, H. ATF2 Promotes Urothelial Cancer Outgrowth via Cooperation with Androgen Receptor Signaling. Endocr. Connect. 2018, 7, 1397–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Gisbergen, K.P.J.M.; Kragten, N.A.M.; Hertoghs, K.M.L.; Wensveen, F.M.; Jonjic, S.; Hamann, J.; Nolte, M.A.; Van Lier, R.A.W. Mouse Hobit Is a Homolog of the Transcriptional Repressor Blimp-1 That Regulates NKT Cell Effector Differentiation. Nat. Immunol. 2012, 13, 864–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, D.J.; Creeden, J.F.; Einloth, K.R.; Gillman, C.E.; Stanbery, L.; Hamouda, D.; Edelman, G.; Dworkin, L.; Nemunaitis, J.J. Resident Memory T Cells and Their Effect on Cancer. Vaccines 2020, 8, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosner, S.; Connor, S.; Sanber, K.; Zahurak, M.; Zhang, T.; Gurumurthy, I.; Zeng, Z.; Presson, B.; Singh, D.; Rayes, R.; et al. Divergent Clinical and Immunologic Outcomes Based on STK11 Co-Mutation Status in Resectable KRAS-Mutant Lung Cancers Following Neoadjuvant Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 31, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, K.S.; Neurath, M.F.; Weigmann, B. Role of the IL-2 Inducible Tyrosine Kinase ITK and Its Inhibitors in Disease Pathogenesis. J. Mol. Med. 2020, 98, 1385–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssefian, L.; Vahidnezhad, H.; Yousefi, M.; Saeidian, A.H.; Azizpour, A.; Touati, A.; Nikbakht, N.; Hesari, K.K.; Adib-Sereshki, M.M.; Zeinali, S.; et al. Inherited Interleukin 2–Inducible T-Cell (ITK) Kinase Deficiency in Siblings with Epidermodysplasia Verruciformis and Hodgkin Lymphoma. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 68, 1938–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, C.C.; Moschos, S.J.; Edmiston, S.N.; Darr, D.B.; Nikolaishvili-Feinberg, N.; Groben, P.A.; Zhou, X.; Kuan, P.F.; Pandey, S.; Chan, K.T.; et al. IL-2 Inducible T-Cell Kinase, a Novel Therapeutic Target in Melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 2167–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Fuentes, J.M.; Hernández-Lemus, E.; Espinal-Enríquez, J. Methylation-Related Genes Involved in Renal Carcinoma Progression. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1225158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Josipović, G.; Tadić, V.; Klasić, M.; Zanki, V.; Bečeheli, I.; Chung, F.; Ghantous, A.; Keser, T.; Madunić, J.; Bošković, M.; et al. Antagonistic and Synergistic Epigenetic Modulation Using Orthologous CRISPR/DCas9-Based Modular System. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 9637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosi, A.; Parisatto, B.; Menegaldo, A.; Spinato, G.; Guido, M.; Del Mistro, A.; Bussani, R.; Zanconati, F.; Tofan-Elli, M.; Tirelli, G.; et al. The Immune Microenvironment of HPV-Positive and HPV-Negative Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Multiparametric Quantitative and Spatial Analysis Unveils a Rationale to Target Treatment-Naïve Tumors with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 41, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snietura, M.; Brewczynski, A.; Kopec, A.; Rutkowski, T. Infiltrates of M2-like Tumour-Associated Macrophages Are Adverse Prognostic Factor in Patients with Human Papillomavirus-Negative but Not in Human Papillomavirus-Positive Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Pathobiology 2020, 87, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moga, M.; Dumitru, M.; Taciuc, I.A.; Musat, G.; Vrinceanu, D.; Georgescu, S.R.; Costache, A.; Costache, D.O.; Anton, A.Z.C. Five-Year Analysis of Head and Neck Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer Incidence, Demographics, and Site Distribution in a Tertiary Care Center. Rom. J. Mil. Med. 2025, 128, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene Set Name | Low Expression (OS Median) | High Expression (OS Median) | Difference in OS Median | p (Log-Rank) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mo. | y. | mo. | y. | mo. | y. | ||

| GOBP_NK_T_CELL_DIFFERENTIATION | 142.3 | 11.86 | 171.1 | 14.26 | 28.8 | 2.40 | 0.015 |

| GOBP_MACROPHAGE_ACTIVATION_INVOLVED_IN_IMMUNE_RESPONSE | 56.9 | 4.74 | Undefined | 0.0637 | |||

| GOBP_NEUTROPHIL_ACTIVATION_INVOLVED_IN_IMMUNE_RESPONSE | 117.5 | 9.79 | 144.7 | 12.06 | 27.2 | 2.27 | 0.1078 |

| GOBP_NEGATIVE_REGULATION_OF_ALPHA_BETA_T_CELL_DIFFERENTIATION | 117.5 | 9.79 | 144.7 | 12.06 | 27.2 | 2.27 | 0.1199 |

| GOBP_NEGATIVE_REGULATION_OF_CD4_POSITIVE_ALPHA_BETA_T_CELL_DIFFERENTIATION | 143.6 | 11.97 | 144.7 | 12.06 | 1.1 | 0.09 | 0.1347 |

| GOBP_REGULATION_OF_NEUTROPHIL_MEDIATED_CYTOTOXICITY | 171.1 | 14.26 | 117.5 | 9.79 | −53.6 | −4.47 | 0.1363 |

| GOBP_NEGATIVE_REGULATION_OF_CD4_POSITIVE_ALPHA_BETA_T_CELL_ACTIVATION | 143.6 | 11.97 | 144.7 | 12.06 | 1.1 | 0.09 | 0.1408 |

| GOBP_NATURAL_KILLER_CELL_ACTIVATION_INVOLVED_IN_IMMUNE_RESPONSE | 143.6 | 11.97 | 144.7 | 12.06 | 1.1 | 0.09 | 0.2272 |

| GOBP_REGULATION_OF_NATURAL_KILLER_CELL_MEDIATED_IMMUNE_RESPONSE_TO_TUMOR_CELL | 117.5 | 9.79 | 144.7 | 12.06 | 27.2 | 2.27 | 0.2787 |

| GOBP_NEGATIVE_REGULATION_OF_REGULATORY_T_CELL_DIFFERENTIATION | 143.6 | 11.97 | 144.7 | 12.06 | 1.1 | 0.09 | 0.2955 |

| GOBP_NEGATIVE_REGULATION_OF_ALPHA_BETA_T_CELL_ACTIVATION | 143.6 | 11.97 | 144.7 | 12.06 | 1.1 | 0.09 | 0.3196 |

| GOBP_NK_T_CELL_PROLIFERATION | 117.5 | 9.79 | 144.7 | 12.06 | 27.2 | 2.27 | 0.3261 |

| GOBP_REGULATORY_T_CELL_DIFFERENTIATION | 143.6 | 11.97 | 144.7 | 12.06 | 1.1 | 0.09 | 0.3296 |

| GOBP_NEGATIVE_REGULATION_OF_CD4_POSITIVE_ALPHA_BETA_T_CELL_PROLIFERATION | 143.6 | 11.97 | 144.7 | 12.06 | 1.1 | 0.09 | 0.3788 |

| GOBP_NEGATIVE_REGULATION_OF_ALPHA_BETA_T_CELL_PROLIFERATION | 143.6 | 11.97 | 144.7 | 12.06 | 1.1 | 0.09 | 0.397 |

| GOBP_NEGATIVE_REGULATION_OF_CD8_POSITIVE_ALPHA_BETA_T_CELL_ACTIVATION | 142.3 | 11.86 | 144.7 | 12.06 | 2.4 | 0.20 | 0.541 |

| GOBP_NK_T_CELL_ACTIVATION | 142.3 | 11.86 | 144.7 | 12.06 | 2.4 | 0.20 | 0.7386 |

| Discrete-Time Survival (Cloglog) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Bias-reduced hazard ratios (Firth-like) | ||

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | p |

| Intercept | 0.02 (0.00–0.47) | 0.014 |

| NKT High vs. Low | 0.13 (0.03–0.49) | 0.003 |

| HPV Positive vs. Negative | 1.34 (0.43–4.17) | 0.612 |

| Smoking Yes vs. No | 0.69 (0.29–1.66) | 0.41 |

| Gene Name | Low Median | High Median | p (Log-Rank) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ITK | 93.13 | 171.1 | 0.0001 |

| ZNF683 | 143.6 | 144.7 | 0.0188 |

| ATF2 | 142.3 | 171.1 | 0.0336 |

| TGFBR2 | 144.7 | 143.6 | 0.0959 |

| PRDM1 | 142.3 | 144.7 | 0.1599 |

| TOX | 142.3 | 171.1 | 0.3135 |

| AP3B1 | 144.7 | 143.6 | 0.535 |

| AP3D1 | 144.7 | 143.6 | 0.7805 |

| ZBTB7B | 171.1 | 142.3 | 0.9916 |

| Gene | Mean M Normal | Mean M Tumour | Delta M | Fold Change | t Stat | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITK | −0.83 | −0.2859256 | 0.55 | 1.46 | 3.25 | 0.003 |

| ZNF683 | 0.96 | 0.84 | −0.11 | 0.93 | −1.15 | 0.26 |

| ATF2 | −2.47 | −2.46 | 0.01 | 1.004 | 0.09 | 0.93 |

| Gene | Mean M Mucosa | Mean M Cancer | Delta M | Fold Change | t Stat | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZNF683 | 0.66 | 0.17 | −0.49 | 0.71 | −2.80 | 0.02 |

| ITK | 0.33 | −0.27 | −0.59 | 0.66 | −1.97 | 0.09 |

| ATF2 | −3.79 | −3.60 | 0.19 | 1.14 | 0.41 | 0.71 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Minarik, L.; Khoueiry, R.; Leskur, M.; Cahais, V.; Herceg, Z.; Glavina Durdov, M.; Benzon, B. Epigenetic Regulation of NKT-Cell-Related Gene Signatures and Prognostic Implications in Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2025, 17, 3666. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223666

Minarik L, Khoueiry R, Leskur M, Cahais V, Herceg Z, Glavina Durdov M, Benzon B. Epigenetic Regulation of NKT-Cell-Related Gene Signatures and Prognostic Implications in Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers. 2025; 17(22):3666. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223666

Chicago/Turabian StyleMinarik, Luka, Rita Khoueiry, Mirela Leskur, Vincent Cahais, Zdenko Herceg, Merica Glavina Durdov, and Benjamin Benzon. 2025. "Epigenetic Regulation of NKT-Cell-Related Gene Signatures and Prognostic Implications in Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma" Cancers 17, no. 22: 3666. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223666

APA StyleMinarik, L., Khoueiry, R., Leskur, M., Cahais, V., Herceg, Z., Glavina Durdov, M., & Benzon, B. (2025). Epigenetic Regulation of NKT-Cell-Related Gene Signatures and Prognostic Implications in Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers, 17(22), 3666. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223666