MRI Reflects Meningioma Biology and Molecular Risk

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Ethics

2.2. Histopathological and Molecular Classification

2.3. MRI Acquisition and Image Processing

- •

- T1-weighted contrast-enhanced sequences (slice thickness ≤ 3 mm);

- •

- FLAIR sequences (slice thickness ≤ 3 mm);

- •

- Additional sequences (T2-weighted, diffusion-weighted) when available.

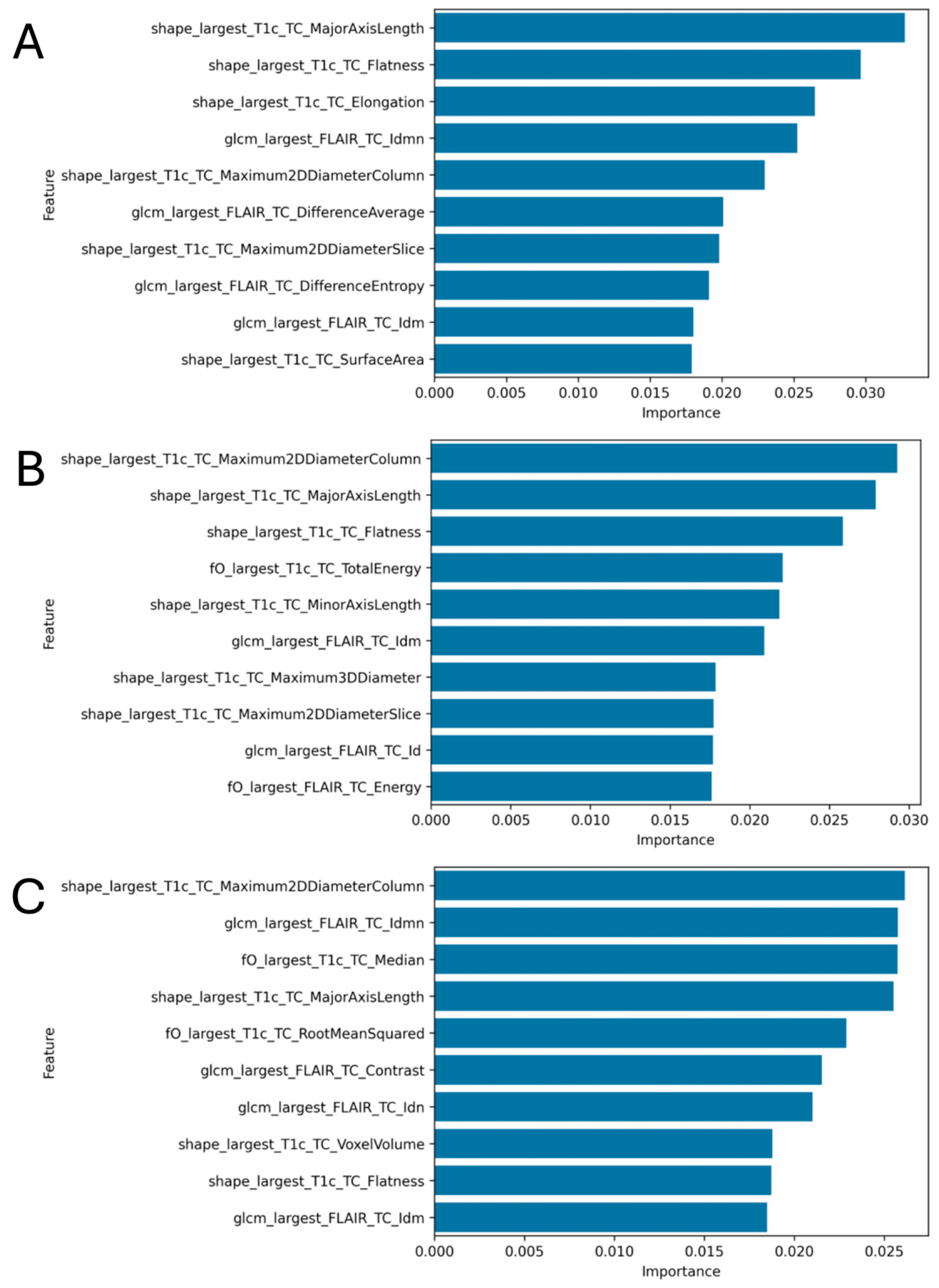

2.4. Radiomics Feature Extraction

- 3D Shape features: Three-dimensional morphological descriptors including volume, surface area, sphericity, flatness, elongation, and various diameter measurements. In total, these are 16 features, all implemented in the RadiomicsShape() class in pyradiomics.

- First-order features: Statistical descriptors of voxel intensity distribution including mean, median, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis. In total, these are 18 features, calculated through RadiomicsFirstOrder().

- Second-order texture features: Gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) derived parameters (23 features), calculated through RadiomicsGLCM().

2.5. Machine Learning Model Development

2.6. Statistical Analysis and Performance Evaluation

- •

- Area Under the Curve (AUC): Primary performance metric;

- •

- Accuracy: Overall classification accuracy;

- •

- F1-score: Weighted harmonic mean of precision and recall;

- •

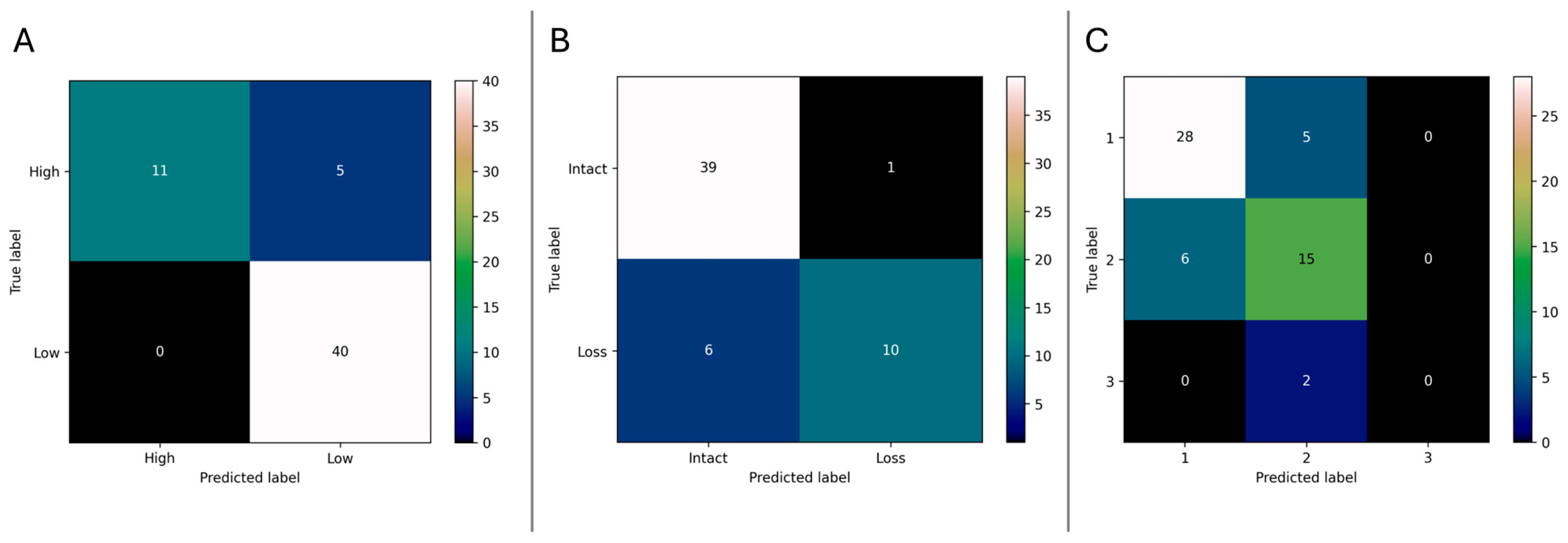

- Confusion matrices: Detailed error analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Characteristics

- •

- WHO Grade: Grade 1 (n = 156, 69%), Grade 2 (n = 57, 25%), Grade 3 (n = 12, 6%);

- •

- 1p Status: Intact (n = 181, 80%), Loss (n = 44, 20%);

- •

- Risk Classification: Low risk (n = 185, 82%), High risk (n = 40, 18%).

3.2. Model Performance

3.2.1. Risk Classification (High vs. Low)

3.2.2. 1p Chromosomal Status Prediction

3.2.3. WHO Grade Classification

3.3. Radiomics Feature Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Significance of Findings

4.2. Biological Basis of Radiomics Findings

4.3. Comparison with Literature and Performance Validation

4.4. Technical Advantages and Clinical Implementation

4.5. Advanced Imaging and Multimodal Integration

4.6. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wiemels, J.; Wrensch, M.; Claus, E.B. Epidemiology and etiology of meningioma. J. Neurooncol. 2010, 99, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Wesseling, P.; Brat, D.J.; Cree, I.A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Hawkins, C.; Ng, H.K.; Pfister, S.M.; Reifenberger, G.; et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A summary. Neuro-Oncology 2021, 23, 1231–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldbrunner, R.; Stavrinou, P.; Jenkinson, M.D.; Sahm, F.; Mawrin, C.; Weber, D.C.; Preusser, M.; Minniti, G.; Lund-Johansen, M.; Lefranc, F.; et al. EANO guideline on the diagnosis and management of meningiomas. Neuro-Oncology 2021, 23, 1821–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.A.; Huang, L.; Ramanathan, D.; Lopez-Gonzalez, M.; Pillai, P.; De Los Reyes, K.; Kumal, M.; Boling, W. Review of Atypical and Anaplastic Meningiomas: Classification, Molecular Biology, and Management. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 565582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.Y.; Park, C.K.; Park, S.H.; Kim, D.G.; Chung, Y.S.; Jung, H.W. Atypical and anaplastic meningiomas: Prognostic implications of clinicopathological features. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2008, 79, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquier, D.; Bijmolt, S.; Veninga, T.; Rezvoy, N.; Villa, S.; Krengli, M.; Weber, D.C.; Baumert, B.G.; Canyilmaz, E.; Yalman, D.; et al. Atypical and malignant meningioma: Outcome and prognostic factors in 119 irradiated patients. A multicenter, retrospective study of the Rare Cancer Network. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2008, 71, 1388–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stessin, A.M.; Schwartz, A.; Judanin, G.; Pannullo, S.C.; Boockvar, J.A.; Schwartz, T.H.; Stieg, P.E.; Wernicke, A.G. Does adjuvant external-beam radiotherapy improve outcomes for nonbenign meningiomas? A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)–based analysis: Clinical article. J. Neurosurg. 2012, 117, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driver, J.; Hoffman, S.E.; Tavakol, S.; Woodward, E.; Maury, E.A.; Bhave, V.; Greenwald, N.F.; Nassiri, F.; Aldape, K.; Zadeh, G.; et al. A molecularly integrated grade for meningioma. Neuro-Oncology 2022, 24, 796–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson-Segerlind, J.; Fletcher-Sandersjöö, A.; von Vogelsang, A.-C.; Persson, O.; Linder, L.K.B.; Förander, P.; Mathiesen, T.; Edström, E.; Elmi-Terander, A. Long-Term Follow-Up, Treatment Strategies, Functional Outcome, and Health-Related Quality of Life after Surgery for WHO Grade 2 and 3 Intracranial Meningiomas. Cancers 2022, 14, 5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahm, F.; Aldape, K.D.; Brastianos, P.K.; Brat, D.J.; Dahiya, S.; von Deimling, A.; Giannini, C.; Gilbert, M.R.; Louis, D.N.; Raleigh, D.R.; et al. cIMPACT-NOW update 8: Clarifications on molecular risk parameters and recommendations for WHO grading of meningiomas. Neuro-Oncology 2025, 27, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trybula, S.J.; Youngblood, M.W.; Karras, C.L.; Murthy, N.K.; Heimberger, A.B.; Lukas, R.V.; Sachdev, S.; Kalapurakal, J.A.; Chandler, J.P.; Brat, D.J.; et al. The Evolving Classification of Meningiomas: Integration of Molecular Discoveries to Inform Patient Care. Cancers 2024, 16, 1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.V.; Yao, S.; Huang, R.Y.; Bi, W.L. Application of radiomics to meningiomas: A systematic review. Neuro-Oncology 2023, 25, 1166–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Z.; Patil, V.; Landry, A.P.; Gui, C.; Ajisebutu, A.; Liu, J.; Saarela, O.; Pugh, S.L.; Won, M.; Patel, Z.; et al. Molecular classification to refine surgical and radiotherapeutic decision-making in meningioma. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 3173–3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, R.J.; Kinahan, P.E.; Hricak, H. Radiomics: Images Are More than Pictures, They Are Data. Radiology 2016, 278, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambin, P.; Rios-Velazquez, E.; Leijenaar, R.; Carvalho, S.; van Stiphout, R.G.P.M.; Granton, P.; Zegers, C.M.L.; Gillies, R.; Boellard, R.; Dekker, A.; et al. Radiomics: Extracting more information from medical images using advanced feature analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2012, 48, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kertels, O.; Delbridge, C.; Sahm, F.; Ehret, F.; Acker, G.; Capper, D.; Peeken, J.C.; Diehl, C.; Griessmair, M.; Metz, M.C.; et al. Imaging meningioma biology: Machine learning predicts integrated risk score in WHO grade 2/3 meningioma. Neurooncol. Adv. 2024, 6, vdae080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohlfing, T.; Zahr, N.M.; Sullivan, E.V.; Pfefferbaum, A. The SRI24 Multi-Channel Brain Atlas: Construction and Applications. Proc. SPIE Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. 2008, 6914, 691409. [Google Scholar]

- Isensee, F.; Schell, M.; Pflueger, I.; Brugnara, G.; Bonekamp, D.; Neuberger, U.; Wick, A.; Schlemmer, H.-P.; Heiland, S.; Wick, W.; et al. Automated brain extraction of multisequence MRI using artificial neural networks. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2019, 40, 4952–4964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofler, F.; Rosier, M.; Astaraki, M.; Möller, H.; Mekki, I.I.; Buchner, J.A.; Schmick, A.; Pfiffer, A.; Oswald, E.; Zimmer, L.; et al. BrainLesion Suite: A Flexible and User-Friendly Framework for Modular Brain Lesion Image Analysis [Internet]. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.09036. https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.09036. [Google Scholar]

- Van Griethuysen, J.J.M.; Fedorov, A.; Parmar, C.; Hosny, A.; Aucoin, N.; Narayan, V.; Beets-Tan, R.G.H.; Fillion-Robin, J.-C.; Pieper, S.; Aerts, H.J.W.L. Computational Radiomics System to Decode the Radiographic Phenotype. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, e104–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwanenburg, A.; Vallières, M.; Abdalah, M.A.; Aerts, H.J.W.L.; Andrearczyk, V.; Apte, A.; Ashrafinia, S.; Bakas, S.; Beukinga, R.J.; Boellaard, R.; et al. The Image Biomarker Standardization Initiative: Standardized Quantitative Radiomics for High-Throughput Image-based Phenotyping. Radiology 2020, 295, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spille, D.C.; Adeli, A.; Sporns, P.B.; Heß, K.; Streckert, E.M.S.; Brokinkel, C.; Mawrin, C.; Paulus, W.; Stummer, W.; Brokinkel, B. Predicting the risk of postoperative recurrence and high-grade histology in patients with intracranial meningiomas using routine preoperative MRI. Neurosurg. Rev. 2021, 44, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niroomand, B.; Mohammadzadeh, I.; Hajikarimloo, B.; Habibi, M.A.; Mohammadzadeh, S.; Bahri, A.M.; Bagheri, M.H.; Albakr, A.; Karmur, B.S.; Borghei-Razavi, H. Machine learning-based models and radiomics: Can they be reliable predictors for meningioma recurrence? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg. Rev. 2025, 48, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.Y.; Hinz, F.; Maas, S.L.N.; Anil, G.; Sievers, P.; Conde-Lopez, C.; Lischalk, J.; Rauh, S.; Eichkorn, T.; Regnery, S.; et al. Analysis of recurrence probability following radiotherapy in patients with CNS WHO grade 2 meningioma using integrated molecular-morphologic classification. Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2023, 5, vdad059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.Y.; Bi, W.L.; Griffith, B.; Kaufmann, T.J.; la Fougère, C.; Schmidt, N.O.; Tonn, J.C.; A Vogelbaum, M.; Wen, P.Y.; Aldape, K.; et al. Imaging and diagnostic advances for intracranial meningiomas. Neuro-Oncology 2019, 21 (Suppl. 1), i44–i61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, M.; Becker, L.; Demerath, T.; Reisert, M.; Erny, D.; Braun, A.; Hauser, T.K.; Grauvogel, J.; Hohenhaus, M.; Urbach, H.; et al. Non-invasive Prediction of Meningioma Tumor Grade by Quantification of Shape-based Radiomics Features and Surface Regularity. Clin. Neuroradiol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Rödiger, L.A.; Shen, T.; Miao, J.; Oudkerk, M. Perfusion MR imaging for differentiation of benign and malignant meningiomas. Neuroradiology 2008, 50, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofler, F.; Berger, C.; Waldmannstetter, D.; Lipkova, J.; Ezhov, I.; Tetteh, G.; Kirschke, J.; Zimmer, C.; Wiestler, B.; Menze, B.H. BraTS Toolkit: Translating BraTS Brain Tumor Segmentation Algorithms Into Clinical and Scientific Practice. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadh, M.J.; Albadr, R.J.; Sur, D.; Yadav, A.; Roopashree, R.; Sangwan, G.; Krithiga, T.; Aminov, Z.; Taher, W.M.; Alwan, M.; et al. Reproducible meningioma grading across multi-center MRI protocols via hybrid radiomic and deep learning features. Neuroradiology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Endpoint | AUC | Accuracy (%) | Weighted F1-Score | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Classification (High/Low) | 0.91 | 91.1 | 0.91 | 68.8 | 100 |

| 1p Status (Loss vs. Intact) | 0.90 | 87.5 | 0.87 | 62.5 | 97.5 |

| WHO-Grade (1/2/3) | 0.89 | 76.8 | 0.75 | – | – |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Canisius, J.; Schuler, J.; Goldberg, M.; Kertels, O.; Metz, M.-C.; Negwer, C.; Yakushev, I.; Meyer, B.; Combs, S.E.; Kirschke, J.S.; et al. MRI Reflects Meningioma Biology and Molecular Risk. Cancers 2025, 17, 3665. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223665

Canisius J, Schuler J, Goldberg M, Kertels O, Metz M-C, Negwer C, Yakushev I, Meyer B, Combs SE, Kirschke JS, et al. MRI Reflects Meningioma Biology and Molecular Risk. Cancers. 2025; 17(22):3665. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223665

Chicago/Turabian StyleCanisius, Julian, Julia Schuler, Maria Goldberg, Olivia Kertels, Marie-Christin Metz, Chiara Negwer, Igor Yakushev, Bernhard Meyer, Stephanie E. Combs, Jan S. Kirschke, and et al. 2025. "MRI Reflects Meningioma Biology and Molecular Risk" Cancers 17, no. 22: 3665. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223665

APA StyleCanisius, J., Schuler, J., Goldberg, M., Kertels, O., Metz, M.-C., Negwer, C., Yakushev, I., Meyer, B., Combs, S. E., Kirschke, J. S., Bernhardt, D., Wiestler, B., & Delbridge, C. (2025). MRI Reflects Meningioma Biology and Molecular Risk. Cancers, 17(22), 3665. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223665