KIT-Mutant Melanoma: Understanding the Pathway to Personalized Therapy

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Clinico-Genetic Correlations

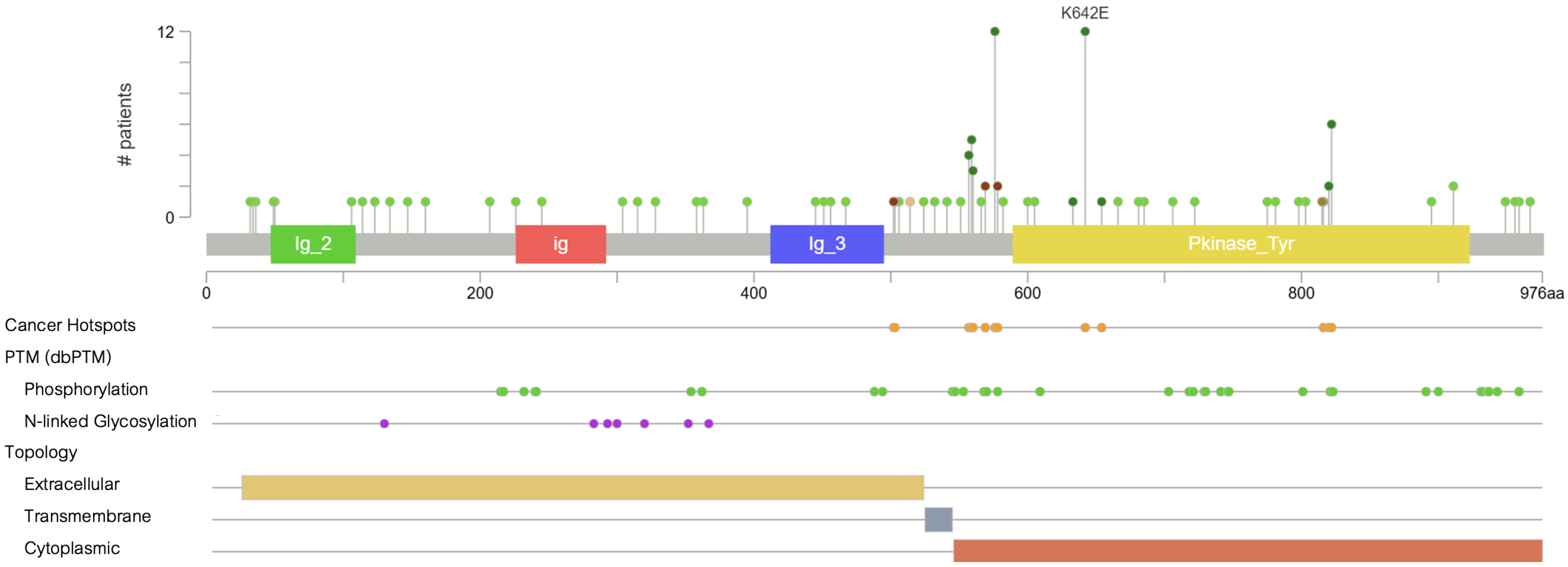

4. Spectrum of KIT Mutations in Melanoma

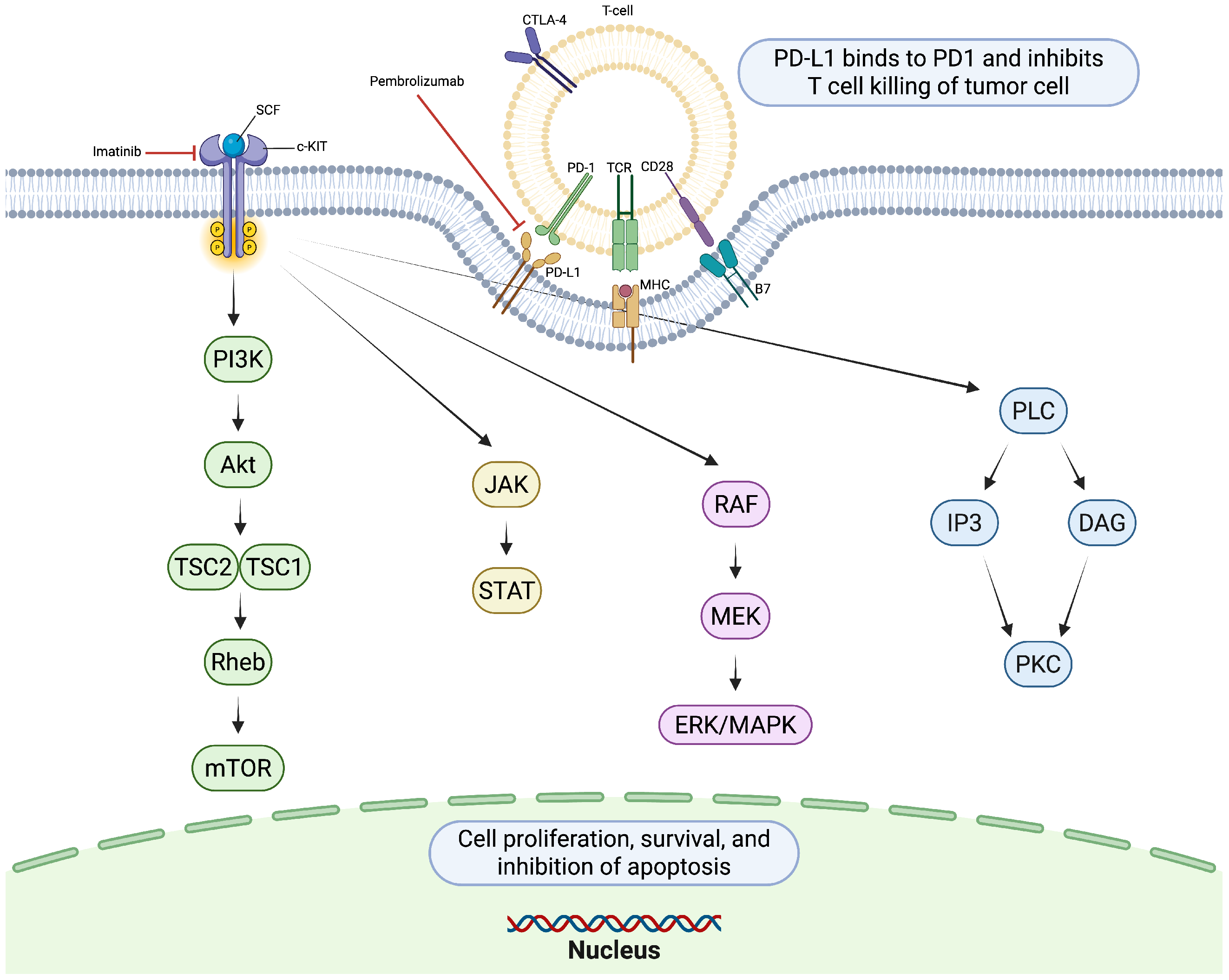

5. Targeted Therapies

5.1. Imatinib

5.2. Nilotinib

5.3. Dasatinib

5.4. Other KIT/Multikinase Inhibitors

6. Immunotherapy in KIT-Mutant Melanoma

7. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

7.1. Clinical Sequencing Guidance

7.2. Critical Unanswered Questions

- What are the mechanisms of primary and acquired resistance to TKI? Mechanisms of resistance in KIT-mutant melanomas are not fully understood, but likely involve secondary KIT mutations (as in GIST) or activation of downstream pathways like MAPK/PI3K regardless of KIT blockade [64]. One study also reported that KIT-mutant melanomas tend to exhibit more aggressive histopathologic features, such as ulceration, vascular invasion, and increased Breslow thickness, which may contribute to or reflect intrinsic resistance phenotypes [65]. Most current data, however, are anecdotal or derived from small trials and case reports. Larger, mechanistically focused studies are needed to uncover these mechanisms and suggest second-line treatments or combination approaches.

- How to maximize therapeutic efficacy in the management of brain metastases? Most TKIs have poor penetration in these areas and many KIT-mutant patients eventually develop brain metastases [7]. Although certain TKIs have shown anecdotal CNS activity, it is difficult to determine to what extent the response is due to KIT inhibition as opposed to the effects on VEGFR or PDFGR when using multitarget kinase inhibitors. Future strategies could include the development of TKIs with improved blood–brain barrier penetration and the earlier use of systemic therapies in high-risk patients.Next-generation TKIs such as avapritinib, which was originally developed for imatinib-resistant GISTs, have shown promising activity in the presence of CNS metastases. In a case of metastatic vulvar melanoma harboring an exon 17 KIT mutation, avapritinib produced a favorable CNS response despite prior treatment failure and high tumor burden [63]. A dedicated clinical study evaluating the efficacy of avapritinib in patients with KIT-mutant melanoma and CNS metastases would be instrumental in defining its therapeutic role in this setting.Beyond pharmacologic optimization, additional strategies to reduce CNS progression may warrant exploration. In other cancers, such as small-cell lung cancer, prophylactic cranial irradiation has been shown to decrease the incidence of brain metastases [66]. While this approach has not been evaluated in melanoma, it remains a theoretical avenue for future investigation.

- What is the role of KIT amplification alone? There is controversy over whether KIT amplification (without mutation) is a predictive biomarker for therapy response. Many of the clinical trials that currently exist include patients selected for KIT mutation or amplification [21,23,24,30]. In GIST, KIT over-expression is primarily driven by epigenetic mechanisms and enhancer domains, rather than KIT amplification [67]. Biomarker stratification for melanoma treatment based on amplification remains underdeveloped.

- How can biomarker-driven clinical trials be developed for KIT-mutant tumors? Few prospective, randomized trials exist that stratify patients by specific KIT mutations. Most evidence comes from small phase II trials or retrospective studies, often mixing KIT-mutant with KIT-amplified or wild-type cases. As a result, there is a need for trials powered to evaluate mutation-specific efficacy (e.g., exon 11 vs. exon 17). In preclinical models of KIT K641E-mutant melanoma, a hybrid biomimetic nanovaccine combining tumor and dendritic cell membranes significantly enhanced dendritic cell maturation, T-cell activation, and inhibited tumor growth. These findings suggest that mutation-specific vaccines may offer a promising adjunct to current treatment methods, specifically immunotherapy [68].

- What is the biological effect of rare KIT mutations? KIT mutations outside of common hotspots (e.g., L576P, K642E) are poorly studied. Rare mutations (e.g., S628N, T632I) show variable drug sensitivity, but lack systematic preclinical or clinical evaluation [20,43]. While common KIT mutations appear to be predictive markers for the efficacy of tyrosine kinase inhibitors, there is currently no consensus on how to interpret or treat patients with these non-canonical variants [16]. To better elucidate the biological and therapeutic implications of these rare variants, future efforts should explore murine models incorporating specific rare mutations, alongside continued reporting of clinical cases and inclusion of such mutations in prospective trials.

- What is the biological role of KIT signaling in melanocytes of non-hair-bearing acral skin? KIT is essential in melanocyte development and migration, but its specific function in glabrous (acral) skin melanocytes is poorly defined [6]. Evidence suggests that KIT expression is preserved in these regions and may be uniquely susceptible to oncogenic transformation, but the developmental cues in acral melanocytes remain unclear [69,70].

- How are acral melanomas related to acral nevi? Molecular analyses reveal that while BRAF and NRAS mutations are common in acral nevi, acral melanomas exhibit a broader spectrum of alterations, including frequent KIT mutations, structural rearrangements, and copy number variations [70]. These KIT mutations are consistently found in acral melanomas but absent in nevi from the same sites, suggesting a distinct oncogenic pathway. These findings raise questions about what triggers KIT-driven transformation in the absence of a nevus precursor.

- What is the role of mechanical stress or anatomic factors that contribute to KIT mutagenesis in acral melanomas? Acral skin is subject to chronic mechanical stress, which has been proposed as a contributing factor to the development of acral melanoma through mechanisms of DNA damage [71]. However, whether this physical stress directly promotes KIT mutagenesis or preferentially selects for KIT-mutant clones remains unclear. A study evaluating the impact of long-term mechanical stress on acral melanoma by comparing clinical and genetic features of lesions on high-pressure areas (heel, forefoot, hallux) versus lower-pressure areas (midfoot, lesser toes) found no significant differences in Breslow thickness or ulceration rates between these sites [72]. Thus, while mechanical stress is broadly implicated in acral melanoma pathogenesis, its specific role in driving KIT mutations requires further investigation.

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CSD | Chronically sun-damaged |

| GIST | Gastrointestinal stromal tumor |

| TKI | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor |

| ICI | Immune checkpoint inhibitor |

| ORR | Objective response rate |

| DCR | Disease control rate |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| OS | Overall survival |

| CR | Complete response |

| PR | Partial response |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

References

- Mallardo, D.; Basile, D.; Vitale, M.G. Advances in Melanoma and Skin Cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundararajan, S.; Thida, A.M.; Yadlapati, S.; Mukkamalla, S.K.R.; Koya, S. Metastatic melanoma. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Curtin, J.A.; Fridlyand, J.; Kageshita, T.; Patel, H.N.; Busam, K.J.; Kutzner, H.; Cho, K.H.; Aiba, S.; Bröcker, E.B.; LeBoit, P.E.; et al. Distinct sets of genetic alterations in melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 2135–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, E.J.; Johnson, D.B.; Sosman, J.A.; Chandra, S. Melanoma: What do all the mutations mean? Cancer 2018, 124, 3490–3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miettinen, M.; Lasota, J. KIT (CD117): A review on expression in normal and neoplastic tissues, and mutations and their clinicopathologic correlation. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2005, 13, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, E.; Tran, T.; Vranic, S.; Levy, A.; Bonfil, R.D. Role and significance of c-KIT receptor tyrosine kinase in cancer: A review. Bosn. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2022, 22, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.D.M.; Guhan, S.; Tsao, H. KIT and melanoma: Biological insights and clinical implications. Yonsei Med. J. 2020, 61, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinrich, M.C.; Corless, C.L.; Demetri, G.D.; Blanke, C.D.; Von Mehren, M.; Joensuu, H.; McGreevey, L.S.; Chen, C.J.; Van den Abbeele, A.D.; Druker, B.J.; et al. Kinase mutations and imatinib response in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 4342–4349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Isozaki, K.; Kinoshita, K.; Ohashi, A.; Shinomura, Y.; Matsuzawa, Y.; Kitamura, Y.; Hirota, S. Imatinib inhibits various types of activating mutant kit found in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Int. J. Cancer 2003, 105, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, H.Z.; Zheng, H.Y.; Li, J. The clinical significance of KIT mutations in melanoma: A meta-analysis. Melanoma Res. 2018, 28, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeilia, A.; Lwin, T.; Li, S.; Tarantino, G.; Tunsiricharoengul, S.; Lawless, A.; Sharova, T.; Liu, D.; Boland, G.M.; Cohen, S. Factors affecting recurrence and survival for patients with high-risk stage II melanoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 31, 2713–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtin, J.A.; Busam, K.; Pinkel, D.; Bastian, B.C. Somatic activation of KIT in distinct subtypes of melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 4340–4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beadling, C.; Jacobson-Dunlop, E.; Hodi, F.S.; Le, C.; Warrick, A.; Patterson, J.; Town, A.; Harlow, A.; Cruz, F., III; Azar, S.; et al. KIT gene mutations and copy number in melanoma subtypes. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 6821–6828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doma, V.; Barbai, T.; Beleaua, M.A.; Kovalszky, I.; Rásó, E.; Tímár, J. KIT mutation incidence and pattern of melanoma in Central Europe. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2020, 26, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodman, S.E.; Davies, M.A. Targeting KIT in melanoma: A paradigm of molecular medicine and targeted therapeutics. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010, 80, 568–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzen, C.Y.; Wu, Y.H.; Tzen, C.Y. Characterization of KIT mutation in melanoma. Dermatol. Sin. 2014, 32, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, B.P.; Antonescu, C.R.; Scott-Browne, J.P.; Comstock, M.L.; Gu, Y.; Tanas, M.R.; Ware, C.B.; Woodell, J. A knock-in mouse model of gastrointestinal stromal tumor harboring kit K641E. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 6631–6639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everdell, E.; Ji, Z.; Njauw, C.N.; Tsao, H. Molecular Analysis of Murine KitK641E Melanoma Progression. JID Innov. 2024, 4, 100266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handolias, D.; Hamilton, A.; Salemi, R.; Tan, A.; Moodie, K.; Kerr, L.; Dobrovic, A.; McArthur, G. Clinical responses observed with imatinib or sorafenib in melanoma patients expressing mutations in KIT. Br. J. Cancer 2010, 102, 1219–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vita, M.; Tisserand, J.C.; de Beauchêne, I.C.; Panel, N.; Tchertanov, L.; Agopian, J.; Mescam-Mancini, L.; Fouet, B.; Fournier, B.; Dubreuil, P.; et al. Characterization of S628N: A novel KIT mutation found in a metastatic melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2014, 150, 1345–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal, R.D.; Antonescu, C.R.; Wolchok, J.D.; Chapman, P.B.; Roman, R.A.; Teitcher, J.; Panageas, K.S.; Busam, K.J.; Chmielowski, B.; Lutzky, J.; et al. KIT as a therapeutic target in metastatic melanoma. JAMA 2011, 305, 2327–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Mao, L.; Chi, Z.; Sheng, X.; Cui, C.; Kong, Y.; Dai, J.; Wang, X.; Li, S.; Tang, B.; et al. Efficacy evaluation of imatinib for the treatment of melanoma: Evidence from a retrospective study. Oncol. Res. 2019, 27, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Si, L.; Kong, Y.; Flaherty, K.T.; Xu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Corless, C.L.; Li, L.; Li, H.; Sheng, X.; et al. Phase II, open-label, single-arm trial of imatinib mesylate in patients with metastatic melanoma harboring c-Kit mutation or amplification. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 2904–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodi, F.S.; Corless, C.L.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Fletcher, J.A.; Zhu, M.; Marino-Enriquez, A.; Friedlander, P.; Gonzalez, R.; Weber, J.S.; Gajewski, T.F.; et al. Imatinib for melanomas harboring mutationally activated or amplified KIT arising on mucosal, acral, and chronically sun-damaged skin. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 3182–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugurel, S.; Hildenbrand, R.; Zimpfer, A.; La Rosee, P.; Paschka, P.; Sucker, A.; Keikavoussi, P.; Becker, J.; Rittgen, W.; Hochhaus, A.; et al. Lack of clinical efficacy of imatinib in metastatic melanoma. Br. J. Cancer 2005, 92, 1398–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Eton, O.; Davis, D.; Frazier, M.; McConkey, D.; Diwan, A.; Papadopoulos, N.; Bedikian, A.; Camacho, L.; Ross, M.; et al. Phase II trial of imatinib mesylate in patients with metastatic melanoma. Br. J. Cancer 2008, 99, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Carvajal, R.; Dummer, R.; Hauschild, A.; Daud, A.; Bastian, B.; Markovic, S.; Queirolo, P.; Arance, A.; Berking, C.; et al. Efficacy and safety of nilotinib in patients with KIT-mutated metastatic or inoperable melanoma: Final results from the global, single-arm, phase II TEAM trial. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 1380–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkin, J.; Marais, R.; Porta, N.; de Castro, D.G.; Parsons, L.; Messiou, C.; Stamp, G.; Thompson, L.; Edmonds, K.; Sarker, S.; et al. Nilotinib in KIT-driven advanced melanoma: Results from the phase II single-arm NICAM trial. Cell Rep. Med. 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delyon, J.; Chevret, S.; Jouary, T.; Dalac, S.; Dalle, S.; Guillot, B.; Arnault, J.P.; Avril, M.F.; Bedane, C.; Bens, G.; et al. STAT3 mediates nilotinib response in KIT-altered melanoma: A phase II multicenter trial of the French Skin Cancer Network. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 138, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.H.; Kim, K.M.; Kwon, M.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, J. Nilotinib in patients with metastatic melanoma harboring KIT gene aberration. Investig. New Drugs 2012, 30, 2008–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal, R.D.; Lawrence, D.P.; Weber, J.S.; Gajewski, T.F.; Gonzalez, R.; Lutzky, J.; O’Day, S.J.; Hamid, O.; Wolchok, J.D.; Chapman, P.B.; et al. Phase II study of nilotinib in melanoma harboring KIT alterations following progression to prior KIT inhibition. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 2289–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Kim, T.M.; Kim, Y.J.; Jang, K.T.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, S.N.; Ahn, M.S.; Hwang, I.G.; Lee, S.; Lee, M.H.; et al. Phase II trial of nilotinib in patients with metastatic malignant melanoma harboring KIT gene aberration: A multicenter trial of Korean Cancer Study Group (UN10-06). Oncologist 2015, 20, 1312–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinsky, K.; Lee, S.; Rubin, K.M.; Lawrence, D.P.; Iafrarte, A.J.; Borger, D.R.; Margolin, K.A.; Leitao, M.M., Jr.; Tarhini, A.A.; Koon, H.B.; et al. A phase 2 trial of dasatinib in patients with locally advanced or stage IV mucosal, acral, or vulvovaginal melanoma: A trial of the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (E2607). Cancer 2017, 123, 2688–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluger, H.M.; Dudek, A.Z.; McCann, C.; Ritacco, J.; Southard, N.; Jilaveanu, L.B.; Molinaro, A.; Sznol, M. A phase 2 trial of dasatinib in advanced melanoma. Cancer 2011, 117, 2202–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchbinder, E.I.; Sosman, J.A.; Lawrence, D.P.; McDermott, D.F.; Ramaiya, N.H.; Van den Abbeele, A.D.; Linette, G.P.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Hodi, F.S. Phase 2 study of sunitinib in patients with metastatic mucosal or acral melanoma. Cancer 2015, 121, 4007–4015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minor, D.R.; Kashani-Sabet, M.; Garrido, M.; O’Day, S.J.; Hamid, O.; Bastian, B.C. Sunitinib therapy for melanoma patients with KIT mutations. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 1457–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gien, L.; Song, Z.; Poklepovic, A.; Collisson, E.; Mitchell, E.; Zweibel, J.; Harris, P.; Gray, R.; Wang, V.; McShane, L.; et al. Phase II study of sunitinib in tumors with c-KIT mutations: Results from the NCI-MATCH ECOG-ACRIN trial (EAY131) subprotocol V. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 174, S86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Jung, M.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, M.; Ahn, M.S.; Choi, M.Y.; Lee, N.R.; Shin, S.J.; Group, K.C.S.; et al. A phase II study on the efficacy of regorafenib in treating patients with c-KIT-mutated metastatic malignant melanoma that progressed after previous treatment (KCSG-UN-14-13). Eur. J. Cancer 2023, 193, 113312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janku, F.; Bauer, S.; Shoumariyeh, K.; Jones, R.L.; Spreafico, A.; Jennings, J.; Psoinos, C.; Meade, J.; Ruiz-Soto, R.; Chi, P. Efficacy and safety of ripretinib in patients with KIT-altered metastatic melanoma. ESMO Open 2022, 7, 100520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyman, K.; Atkins, M.B.; Prieto, V.; Eton, O.; McDermott, D.F.; Hubbard, F.; Byrnes, C.; Sanders, K.; Sosman, J.A. Multicenter phase II trial of high-dose imatinib mesylate in metastatic melanoma: Significant toxicity with no clinical efficacy. Cancer Interdiscip. Int. J. Am. Cancer Soc. 2006, 106, 2005–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudoux, O.; Ehret, M.; Criquet, E.; Franceschi, J.; Durlach, A.; Oudart, J.B.; Visseaux, L.; Grange, F. Response to imatinib in a patient with double-mutant KIT metastatic penile Melanoma. Acta Dermato-Venereologica 2021, 101, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, M.; Casasola, R. Complete response in a melanoma patient treated with imatinib. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2012, 126, 638–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlova, K.V.; Yanus, G.A.; Aleksakhina, S.N.; Venina, A.R.; Iyevleva, A.G.; Demidov, L.V.; Imyanitov, E.N. Lack of Response to Imatinib in Melanoma Carrying Rare KIT Mutation p.T632I. Case Rep. Oncol. 2019, 12, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapisuwon, S.; Parks, K.; Al-Refaie, W.; Atkins, M.B. Novel somatic KIT exon 8 mutation with dramatic response to imatinib in a patient with mucosal melanoma: A case report. Melanoma Res. 2014, 24, 509–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, N.C.; Richardson, J.A.; Egorin, M.; Ilaria, R.L., Jr. The CNS is a sanctuary for leukemic cells in mice receiving imatinib mesylate for Bcr/Abl-induced leukemia. Blood 2003, 101, 5010–5013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantarjian, H.M.; Giles, F.; Gattermann, N.; Bhalla, K.; Alimena, G.; Palandri, F.; Ossenkoppele, G.J.; Nicolini, F.E.; O’Brien, S.G.; Litzow, M.; et al. Nilotinib (formerly AMN107), a highly selective BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitor, is effective in patients with Philadelphia chromosome–positive chronic myelogenous leukemia in chronic phase following imatinib resistance and intolerance. Blood J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 2007, 110, 3540–3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkeraye, S.; Dadban, A.; Lok, C.; Arnault, J.; Chaby, G. C-Kit non-mutated metastatic melanoma showing positive response to Nilotinib. Dermatol. Online J. 2016, 22, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, L.J.; Lee, F.Y.; Chen, P.; Norris, D.; Barrish, J.C.; Behnia, K.; Castaneda, S.; Cornelius, L.A.; Das, J.; Doweyko, A.M.; et al. Discovery of N-(2-chloro-6-methyl-phenyl)-2-(6-(4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-piperazin-1-yl)-2-methylpyrimidin-4-ylamino) thiazole-5-carboxamide (BMS-354825), a dual Src/Abl kinase inhibitor with potent antitumor activity in preclinical assays. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 6658–6661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonescu, C.R.; Busam, K.J.; Francone, T.D.; Wong, G.C.; Guo, T.; Agaram, N.P.; Besmer, P.; Jungbluth, A.; Gimbel, M.; Chen, C.T.; et al. L576P KIT mutation in anal melanomas correlates with KIT protein expression and is sensitive to specific kinase inhibition. Int. J. Cancer 2007, 121, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodman, S.E.; Trent, J.C.; Stemke-Hale, K.; Lazar, A.J.; Pricl, S.; Pavan, G.M.; Fermeglia, M.; Gopal, Y.V.; Yang, D.; Podoloff, D.A.; et al. Activity of dasatinib against L576P KIT mutant melanoma: Molecular, cellular, and clinical correlates. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2009, 8, 2079–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, T.; Tsubaki, M.; Kato, N.; Genno, S.; Ichimura, E.; Enomoto, A.; Imano, M.; Satou, T.; Nishida, S. Sorafenib treatment of metastatic melanoma with c-Kit aberration reduces tumor growth and promotes survival. Oncol. Lett. 2021, 22, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintás-Cardama, A.; Lazar, A.J.; Woodman, S.E.; Kim, K.; Ross, M.; Hwu, P. Complete response of stage IV anal mucosal melanoma expressing KIT Val560Asp to the multikinase inhibitor sorafenib. Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 2008, 5, 737–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosvicova, J.; Lukesova, S.; Kopecky, J.; Grim, J.; Papik, Z.; Kolarova, R.; Navratilova, B.; Dubreuil, P.; Agopian, J.; Mansfield, C.; et al. Rapid and clinically significant response to masitinib in the treatment of mucosal primary esophageal melanoma with somatic KIT exon 11 mutation involving brain metastases: A case report. Biomed. Pap. Med. Fac. Univ. Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 2015, 159, 695–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rausch, M.P.; Hastings, K.T. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in the Treatment of Melanoma: From Basic Science to Clinical Application; Exon Publications: Brisbane, Australia, 2017; pp. 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKean, M.; Oba, J.; Ma, J.; Roth, K.G.; Wang, W.L.; Macedo, M.P.; Carapeto, F.C.; Haydu, L.E.; Siroy, A.E.; Vo, P.; et al. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor and immune checkpoint inhibitor responses in KIT-mutant metastatic melanoma. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2019, 139, 728–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Xu, Y.; Yan, W.; Wang, C.; Hu, T.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y. A real-world study of adjuvant anti-PD-1 immunotherapy on stage III melanoma with BRAF, NRAS, and KIT mutations. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 15945–15954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samlowski, W. The effect of non-overlapping somatic mutations in BRAF, NRAS, NF1, or CKIT on the incidence and outcome of brain metastases during immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy of metastatic melanoma. Cancers 2024, 16, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdou, Y.; Kapoor, A.; Hamad, L.; Ernstoff, M.S. Combination of pembrolizumab and imatinib in a patient with double KIT mutant melanoma: A case report. Medicine 2019, 98, e17769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu-Fujii, T.; Nomura, M.; Otsuka, A.; Ishida, Y.; Doi, K.; Matsumoto, S.; Muto, M.; Kabashima, K. Response to imatinib in vaginal melanoma with KIT p. Val559Gly mutation previously treated with nivolumab, pembrolizumab and ipilimumab. J. Dermatol. 2019, 46, e203–e204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, I.; Tanese, K.; Fukuda, K.; Fusumae, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Sato, Y.; Amagai, M.; Funakoshi, T. Imatinib mesylate in combination with pembrolizumab in patients with advanced KIT-mutant melanoma following progression on standard therapy: A phase I/II trial and study protocol. Medicine 2021, 100, e27832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decoster, L.; Vande Broek, I.; Neyns, B.; Majois, F.; Baurain, J.F.; Rottey, S.; Rorive, A.; Anckaert, E.; De Mey, J.; De Brakeleer, S.; et al. Biomarker analysis in a phase II study of sunitinib in patients with advanced melanoma. Anticancer. Res. 2015, 35, 6893–6899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, R. A new tool for the KIT. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 8, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocorocchio, E.; Pala, L.; Conforti, F.; Guerini-Rocco, E.; De Pas, T.; Ferrucci, P.F. Successful treatment with avapritinib in patient with mucosal metastatic melanoma. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2020, 12, 1758835920946158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, J.; Scurr, L.; Becker, T.; Kefford, R.; Rizos, H. The MAPK pathway functions as a redundant survival signal that reinforces the PI3K cascade in c-Kit mutant melanoma. Oncogene 2014, 33, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán-Esteban, D.; Garcí-Casado, Z.; Manrique-Silva, E.; Virós, A.; Kumar, R.; Furney, S.; López-Guerrero, J.A.; Requena, C.; Bañuls, J.; Traves, V.; et al. Distribution and clinical role of KIT gene mutations in melanoma according to subtype: A study of 492 Spanish patients. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2021, 31, 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotman, B.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Kramer, G.; Rankin, E.; Snee, M.; Hatton, M.; Postmus, P.; Collette, L.; Musat, E.; Senan, S. Prophylactic cranial irradiation in extensive small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Abdihamid, O.; Tan, F.; Zhou, H.; Liu, H.; Li, Z.; Xiao, S.; Li, B. KIT mutations and expression: Current knowledge and new insights for overcoming IM resistance in GIST. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, K.; Ji, Z.; Njauw, C.N.; Rajadurai, A.; Bhayana, B.; Sullivan, R.J.; Kim, J.O.; Tsao, H. Fabrication and functional validation of a hybrid biomimetic nanovaccine (HBNV) against KitK641E-mutant melanoma. Bioact. Mater. 2025, 46, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, B.; Cai, X.; Kong, Y.Y.; Yang, F.; Shen, X.X.; Wang, L.W.; Kong, J.C. Analysis of KIT expression and gene mutation in human acral melanoma: With a comparison between primary tumors and corresponding metastases/recurrences. Hum. Pathol. 2013, 44, 1472–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smalley, K.S.; Teer, J.K.; Chen, Y.A.; Wu, J.Y.; Yao, J.; Koomen, J.M.; Chen, W.S.; Rodriguez-Waitkus, P.; Karreth, F.A.; Messina, J.L. A mutational survey of acral nevi. JAMA Dermatol. 2021, 157, 831–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, L.A.D.; Aguiar, F.C.; Smalley, K.S.; Possik, P.A. Acral melanoma: New insights into the immune and genomic landscape. Neoplasia 2023, 46, 100947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.S.; Kim, J.H.; Cho, M.Y.; Chung, K.Y.; Roh, M.R. PTEN promoter hypermethylation is associated with breslow thickness in acral melanoma on the heel, forefoot, and hallux. Ann. Dermatol. 2020, 33, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Drug (mg) | N | ORR (%) | DCR (%) | mPFS (mo) | mOS (mo) | Mutation Details | Melanoma Subtype | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMA 400 BID | 25 | 16 | 36 | 2.8 | 10.7 | Exon 9: 1 (4%) Exon 11: 9 (36%) Exon 13: 6 (24%) Exon 17: 2 (8%) Exon 18: 3 (12%) KIT WT: 4 (16%) | Mucosal: 13 (52%) Acral: 8 (32%) CSD: 4 (16%) | Carvajal et al. [21] |

| IMA 400 QD | 78 | 21.8 | 60.3 | 4.2 | 13.1 | Exon 9: 7 (9%) Exon 11: 31 (40%) Exon 13: 16 (21%) Exon 17: 5 (6%) Exon 18: 3 (4%) Multiple mutations: 13 (17%) KIT amp: 2 (3%) | Mucosal: 16 (20%) Acral: 42 (54%) CSD: 14 (18%) Others: 6 (8%) | Wei et al. [22] |

| IMA 400 QD/BID | 43 | 23.3 | 53.5 | 3.5 | 12 | Exon 9: 3 (7%) Exon 11: 17 (39%) Exon 13: 9 (21%) Exon 17: 5 (12%) Exon 18: 6 (14%) KIT amp: 3 (7%) | Mucosal: 11 (25%) Acral: 21 (49%) CSD: 5 (12%) NSD: 4 (9%) Others: 2 (5%) | Guo et al. [23] |

| IMA 400 QD/BID | 24 | 29.2 | 50 | 3.7 (TTP) | 12.5 | Exon 11: 9 (38%) Exon 13: 3 (12%) Exon 17: 1 (4%) KIT amp: 11 (46%) | Mucosal: 17 (71%) Acral: 6 (25%) CSD: 1 (4%) | Hodi et al. [24] |

| NIL 400 BID | 42 | 26.2 | 73.8 | 4.2 | 18 | Exon 9: 2 (5%) Exon 11: 26 (62%) Exon 13: 13 (31%) Exon 17: 1 (2%) | Mucosal: 20 (48%) Acral: 20 (48%) CSD: 2 (4%) | Guo et al. [27] |

| NIL 400 BID | 26 | - | - | 3.7 | 7.7 | Exon 9: 0 (0%) Exon 11: 20 (77%) Exon 13: 4 (15%) Exon 17: 2 (8%) | Mucosal: 20 (77%) Acral: 6 (23%) CSD: 0 (0%) | Larkin et al. [28] |

| NIL 400 BID | 25 | 16 | 64 | 6 | 13.2 | Exon 9: 0 (0%) Exon 11: 11 (44%) Exon 13: 8 (32%) Exon 17: 3 (12%) KIT WT: 3 (12%) | Mucosal: 10 (40%) Acral: 9 (36%) CSD: 1 (4%) Other: 5 (20%) | Delyon et al. [29] |

| NIL 400 BID | 9 | 22.2 | 77.8 | 2.5 | 7.7 | Exon 9: 0 (0%) Exon 11: 3 (33%) Exon 13: 0 (0%) Exon 17: 0 (0%) Exon 18: 0 (0%) KIT amp: 6 (66%) | Mucosal: 1 (11%) Acral: 8 (88%) CSD: 0 (0%) | Cho et al. [30] |

| NIL 400 BID | 19 | 15.8 | 52.6 | 3.3 (TTP) | 9.1 | Exon 9: 0 (0%) Exon 11: 9 (47%) Exon 13: 5 (26%) Exon 17: 2 (11%) Exon 18: 1 (5%) KIT WT: 2 (11%) | Mucosal: 12 (63%) Acral: 4 (21%) CSD: 3 (16%) | Carvajal et al. [31] |

| NIL 400 BID | 42 | 16.7 | 57.1 | 3.3 | 11.9 | Exon 9: 1 (2%) Exon 11: 14 (33%) Exon 13: 4 (10%) Exon 17: 3 (7%) Exon 18: 2 (5%) Exon 11, 13: 2 (5%) Exon 11, 18: 1 (2%) KIT WT: 15 (36%) | Mucosal: 12 (29%) Acral: 21 (50%) Cutaneous: 9 (21%) | Lee et al. [32] |

| DAS 70 BID | 22 | 18.2 | 50 | 2.1 | 7.5 | Exon 9: 0 (0%) Exon 11: 14 (63%) Exon 13: 2 (9%) Exon 17: 4 (18%) Exon 11, 13: 1 (5%) Exon 11, 17: 1 (5%) | Mucosal: 8 (36%) Acral: 6 (27%) CSD: 0 (0%) Vulvovaginal: 8 (36%) | Kalinksy et al. [33] |

| DAS 70 BID | 39 | 5 | - | 2 | 13.8 | - | Mucosal: 5 (13%) Acral: 5 (13%) Cutaneous: 22 (56%) Ocular: 4 (10%) Unknown: 3 (8%) | Kluger et al. [34] |

| A: SUN 50 QD, B: SUN 37.5 QD | A: 21, B: 31 | 44 | - | 3.1 | 7.7 | Exon 9: 0 (0%) Exon 11: 8 (15%) Exon 13: 2 (4%) Exon 17: 3 (6%) KIT WT: 39 (75%) | - | Buchbinder et al. [35] |

| SUN 50 QD | 10 | 40 | 50 | - | - | Exon 9: 0 (0%) Exon 11: 9 (90%) Exon 13: 1 (10%) Exon 17: 0 (0%) Exon 18: 0 (0%) | Mucosal: 5 (50%) Acral: 3 (30%) CSD: 2 (20%) | Minor et al. [36] |

| SUN 50 QD | 9 | 22.2 | 66.2 | 4.2 | 26.4 | All patients had KIT mutations; exact subtypes not detailed | Mucosal: 2 (22%) Cutaneous: 1 (11%) Other: 1 (11%) Non-melanoma: 5 (56%) | Gien et al. [37] |

| REG 160 QD | 23 | 30.4 | 73.9 | 7.1 | 21.5 | Exon 11: 13 (57%) Exon 13: 4 (17%) Exon 17: 4 (17%) Multiple mutations: 2 (9%) | Mucosal: 6 (26%) Acral: 9 (39%) CSD: 3 (13%) Unknown: 5 (22%) | Kim et al. [38] |

| RIP 150 QD | 26 | 23 | - | 7.3 | - | Exon 11: 8 (31%) Exon 13: 4 (15%) Exon 17: 11 (42%) Exon 18: 1 (4%) Exon 11, 17: 1 (4%) KIT amp: 1 (4%) | Mucosal: 15 (58%) Acral: 4 (15%) Desmoplastic: 1 (4%) Splitzoid: 1 (4%) Unknown: 5 (19%) | Janku et al. [39] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaveti, A.; Sullivan, R.J.; Tsao, H. KIT-Mutant Melanoma: Understanding the Pathway to Personalized Therapy. Cancers 2025, 17, 3644. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223644

Kaveti A, Sullivan RJ, Tsao H. KIT-Mutant Melanoma: Understanding the Pathway to Personalized Therapy. Cancers. 2025; 17(22):3644. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223644

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaveti, Aditi, Ryan J. Sullivan, and Hensin Tsao. 2025. "KIT-Mutant Melanoma: Understanding the Pathway to Personalized Therapy" Cancers 17, no. 22: 3644. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223644

APA StyleKaveti, A., Sullivan, R. J., & Tsao, H. (2025). KIT-Mutant Melanoma: Understanding the Pathway to Personalized Therapy. Cancers, 17(22), 3644. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223644