The Microbiome and Genitourinary Cancers: A New Frontier

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Epidemiology and Therapeutics in UC and RCC

3. Microbiome and Carcinogenesis

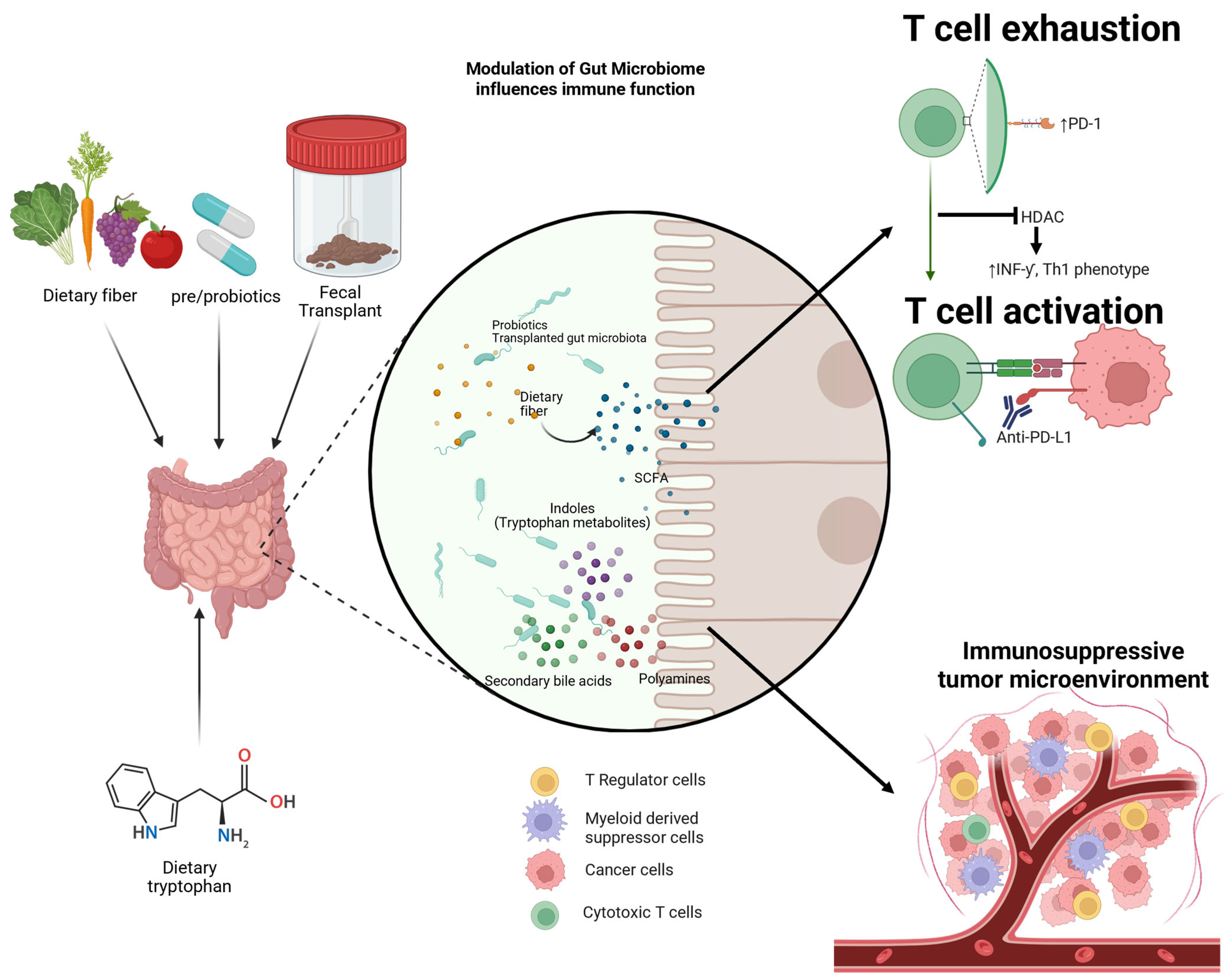

4. Microbiome and Immune Interaction

5. Associations of the Microbiome and ICI Efficacy

6. Antibiotics and Dysbiosis

7. Therapeutic Approaches to Modifying the Microbiome to Enhance ICI

7.1. FMT

7.2. Probiotics

7.3. Diet and Prebiotics

8. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, D. Progress in the chemotherapy of metastatic cancer of the urinary tract. Cancer 2003, 97, 2050–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, J.T.; Bokemeyer, C. Chemotherapy for renal cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 1999, 19, 1541–1543. [Google Scholar]

- Motzer, R.J.; Tannir, N.M.; McDermott, D.F.; Aren Frontera, O.; Melichar, B.; Choueiri, T.K.; Plimack, E.R.; Barthélémy, P.; Porta, C.; George, S.; et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab versus Sunitinib in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1277–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powles, T.; Park, S.H.; Voog, E.; Caserta, C.; Valderrama, B.P.; Gurney, H.; Kalofonos, H.; Radulović, S.; Demey, W.; Ullén, A.; et al. Avelumab Maintenance Therapy for Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choueiri, T.K.; Tomczak, P.; Park, S.H.; Venugopal, B.; Ferguson, T.; Symeonides, S.N.; Hajek, J.; Chang, Y.-H.; Lee, J.-L.; Sarwar, N.; et al. Overall Survival with Adjuvant Pembrolizumab in Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 1359–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powles, T.; Catto, J.W.; Galsky, M.D.; Al-Ahmadie, H.; Meeks, J.J.; Nishiyama, H.; Vu, T.Q.; Antonuzzo, L.; Wiechno, P.; Atduev, V.; et al. Perioperative Durvalumab with Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Operable Bladder Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1773–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.; Valderrama, B.P.; Gupta, S.; Bedke, J.; Kikuchi, E.; Hoffman-Censits, J.; Iyer, G.; Vulsteke, C.; Park, S.H.; Shin, S.J.; et al. Enfortumab Vedotin and Pembrolizumab in Untreated Advanced Urothelial Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heijden, M.S.; Sonpavde, G.; Powles, T.; Necchi, A.; Burotto, M.; Schenker, M.; Sade, J.P.; Bamias, A.; Beuzeboc, P.; Bedke, J.; et al. Nivolumab plus Gemcitabine–Cisplatin in Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1778–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rini, B.I.; Plimack, E.R.; Stus, V.; Gafanov, R.; Waddell, T.; Nosov, D.; Pouliot, F.; Alekseev, B.; Soulières, D.; Melichar, B.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma: 5-year survival and biomarker analyses of the phase 3 KEYNOTE-426 trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 3475–3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.-B.; Hu, L.-S.; Huang, W.-J.; Zhou, Z.-Z.; Luo, H.-Y.; Tian, X.-P. Comparative investigation of neoadjuvant immunotherapy versus adjuvant immunotherapy in perioperative patients with cancer: A global-scale, cross-sectional, and large-sample informatics study. Int. J. Surg. 2024, 110, 4660–4671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, J.; Petrylak, D.; Flaig, T.; Hoimes, C.; Gupta, S.; O’Donnell, P.; Mar, N.; Friedlander, T.; Tagawa, S.; Bilen, M.; et al. 1968P Study EV-103 dose escalation/cohort A (DE/A): 5y follow-up of first-line (1L) enfortumab vedotin (EV) + pembrolizumab (P) in cisplatin (CIS)-ineligible locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (la/mUC). Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, S1139–S1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannir, N.; Albigès, L.; McDermott, D.; Burotto, M.; Choueiri, T.; Hammers, H.; Barthélémy, P.; Plimack, E.; Porta, C.; George, S.; et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib for first-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma: Extended 8-year follow-up results of efficacy and safety from the phase III CheckMate 214 trial. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, 1026–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzer, R.J.; Escudier, B.; Burotto, M.; Powles, T.; Apolo, A.B.; Bourlon, M.T.; Shah, A.Y.; Porta, C.; Suárez, C.; Barrios, C.H.; et al. Nivolumab plus cabozantinib (N+C) vs. sunitinib (S) for previously untreated advanced renal cell carcinoma (aRCC): Final follow-up results from the CheckMate 9ER trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzer, R.J.; Porta, C.; Eto, M.; Powles, T.; Grünwald, V.; Hutson, T.E.; Alekseev, B.; Rha, S.Y.; Merchan, J.; Goh, J.C.; et al. Lenvatinib Plus Pembrolizumab Versus Sunitinib in First-Line Treatment of Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma: Final Prespecified Overall Survival Analysis of CLEAR, a Phase III Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 1222–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rysz, J.; Ławiński, J.; Franczyk, B.; Gluba-Sagr, A. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma (ccRCC). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xu, R.; He, D.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, R.; Zhu, R.; Gong, L.; et al. CD8+ T effector and immune checkpoint signatures predict prognosis and responsiveness to immunotherapy in bladder cancer. Oncogene 2021, 40, 6223–6234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, V.; Spencer, C.N.; Nezi, L.; Reuben, A.; Andrews, M.C.; Karpinets, T.V.; Prieto, P.A.; Vicente, D.; Hoffman, K.; Wei, S.C.; et al. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti–PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science 2018, 359, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routy, B.; le Chatelier, E.; DeRosa, L.; Duong, C.P.M.; Alou, M.T.; Daillère, R.; Fluckiger, A.; Messaoudene, M.; Rauber, C.; Roberti, M.P.; et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1–based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 2018, 359, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derosa, L.; Routy, B.; Fidelle, M.; Iebba, V.; Alla, L.; Pasolli, E.; Segata, N.; Desnoyer, A.; Pietrantonio, F.; Ferrere, G.; et al. Gut Bacteria Composition Drives Primary Resistance to Cancer Immunotherapy in Renal Cell Carcinoma Patients. Eur. Urol. 2020, 78, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivan, A.; Corrales, L.; Hubert, N.; Williams, J.B.; Aquino-Michaels, K.; Earley, Z.M.; Benyamin, F.W.; Lei, Y.M.; Jabri, B.; Alegre, M.-L.; et al. Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti-PD-L1 efficacy. Science 2015, 350, 1084–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostic, A.D.; Chun, E.; Robertson, L.; Glickman, J.N.; Gallini, C.A.; Michaud, M.; Clancy, T.E.; Chung, D.C.; Lochhead, P.; Hold, G.L.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum Potentiates Intestinal Tumorigenesis and Modulates the Tumor-Immune Microenvironment. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.H. Control of lymphocyte functions by gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Kim, M.; Kang, S.; Jannasch, A.; Cooper, B.; Patterson, J.; Kim, C. Short-chain fatty acids induce both effector and regulatory T cells by suppression of histone deacetylases and regulation of the mTOR–S6K pathway. Mucosal Immunol. 2014, 8, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Sun, M.; Wu, W.; Yang, W.; Huang, X.; Xiao, Y.; Ma, C.; Xu, L.; Yao, S.; Liu, Z.; et al. Microbiota Metabolite Butyrate Differentially Regulates Th1 and Th17 Cells’ Differentiation and Function in Induction of Colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2019, 25, 1450–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, J.J.; Purdue, M.P.; Signoretti, S.; Swanton, C.; Albiges, L.; Schmidinger, M.; Heng, D.Y.; Larkin, J.; Ficarra, V. Renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2017, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alouini, S. Risk Factors Associated with Urothelial Bladder Cancer. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukavina, L.; Bensalah, K.; Bray, F.; Carlo, M.; Challacombe, B.; Karam, J.A.; Kassouf, W.; Mitchell, T.; Montironi, R.; O’BRien, T.; et al. Epidemiology of Renal Cell Carcinoma: 2022 Update. Eur. Urol. 2022, 82, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fradet, Y.; Bellmunt, J.; Vaughn, D.J.; Lee, J.L.; Fong, L.; Vogelzang, N.J.; Climent, M.A.; Petrylak, D.P.; Choueiri, T.K.; Necchi, A.; et al. Randomized phase III KEYNOTE-045 trial of pembrolizumab versus paclitaxel, docetaxel, or vinflunine in recurrent advanced urothelial cancer: Results of >2 years of follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 970–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choueiri, T.K.; Escudier, B.; McDermott, D.F.; Burotto, M.; Hammers, H.J.; Plimack, E.R.; Porta, C.; George, S.; Powles, T.; Donskov, F.; et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab vs. sunitinib for first-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma: Final analysis from the phase 3 CheckMate 214 trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 4505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzer, R.J.; Powles, T.; Burotto, M.; Escudier, B.; Bourlon, M.T.; Shah, A.Y.; Suárez, C.; Hamzaj, A.; Porta, C.; Hocking, C.M.; et al. Nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib in first-line treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma (CheckMate 9ER): Long-term follow-up results from an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 888–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navani, V.; Heng, D.Y.C. Treatment Selection in First-line Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma—The Contemporary Treatment Paradigm in the Age of Combination Therapy. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voss, M.H.; Gurney, H.; Atduev, V.; Suárez, C.; Climent, M.Á.; Pook, D.W.; Tomczak, P.; Barthelemy, P.; Lee, J.-L.; Nalbandian, T.; et al. First-line pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib for non–clear cell renal carcinomas (nccRCC): Extended follow-up of the phase 2 KEYNOTE-B61 study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, L.; Albiges, L.; Ahrens, M.; Gross-Goupil, M.; Boleti, E.; Gravis, G.; Fléchon, A.; Grimm, M.-O.; Bedke, J.; Barthélémy, P.; et al. Prospective randomized phase-II trial of ipilimumab/nivolumab versus standard of care in non-clear cell renal cell cancer - results of the SUNNIFORECAST trial. Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 796–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, N.B.; Powles, T.; Tomczak, P.; Park, S.H.; Venugopal, B.; Symeonides, S.N.; Ferguson, T.; Chang, W.Y.H.; Lee, J.L.; Sawrycki, P.; et al. Five-year follow-up results from the phase 3 KEYNOTE-564 study of adjuvant pembrolizumab (pembro) for the treatment of clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choueiri, T.K.; Tomczak, P.; Park, S.H.; Venugopal, B.; Ferguson, T.; Chang, Y.-H.; Hajek, J.; Symeonides, S.N.; Lee, J.L.; Sarwar, N.; et al. Adjuvant Pembrolizumab after Nephrectomy in Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 683–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Heijden, M.S.; Galsky, M.D.; Powles, T.; Necchi, A.; Ye, D.; Zhang, P.; Bamias, A.; Maroto-Rey, P.; Pavic, M.; Bedke, J.; et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab (NIVO+IPI) vs. gemcitabine-carboplatin (gem-carbo) chemotherapy for previously untreated unresectable or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (mUC): Final results for cisplatin-ineligible patients from the CheckMate 901 trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 4500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.; Van Der Heijden, M.S.; Loriot, Y.; Bedke, J.; Valderrama, B.P.; Iyer, G.; Kikuchi, E.; Hoffman-Censits, J.; Vulsteke, C.; Drakaki, A.; et al. EV-302: Updated analysis from the phase 3 global study of enfortumab vedotin in combination with pembrolizumab (EV+P) vs. chemotherapy (chemo) in previously untreated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (la/mUC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galsky, M.D.; Witjes, J.A.; Gschwend, J.E.; Milowsky, M.I.; Schenker, M.; Valderrama, B.P.; Tomita, Y.; Bamias, A.; Lebret, T.; Shariat, S.F.; et al. Adjuvant Nivolumab in High-Risk Muscle-Invasive Urothelial Carcinoma: Expanded Efficacy From CheckMate 274. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajorin, D.F.; Witjes, J.A.; Gschwend, J.E.; Schenker, M.; Valderrama, B.P.; Tomita, Y.; Bamias, A.; Lebret, T.; Shariat, S.F.; Park, S.H.; et al. Adjuvant Nivolumab versus Placebo in Muscle-Invasive Urothelial Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 2102–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balar, A.V.; Kamat, A.M.; Kulkarni, G.S.; Uchio, E.M.; Boormans, J.L.; Roumiguié, M.; Krieger, L.E.M.; Singer, E.A.; Bajorin, D.F.; Grivas, P.; et al. Pembrolizumab monotherapy for the treatment of high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer unre-sponsive to BCG (KEYNOTE-057): An open-label, single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Kidney Cancer, Version 1.2026. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/kidney.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Bladder Cancer, Version 1.2025. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/bladder.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Sati, N.; Boyne, D.J.; Cheung, W.Y.; Cash, S.B.; Arora, P. Factors Modifying the Associations of Single or Combination Programmed Cell Death 1 and Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1 Inhibitor Therapies With Survival Outcomes in Patients With Metastatic Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.-N.; Yu, E.Y.-W.; Zeegers, M.P.; Wesselius, A. The association between diet and bladder cancer risk: A two-sample mendelian randomization. Eur. J. Nutr. 2025, 64, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tini, S.; Baima, J.; Pigni, S.; Antoniotti, V.; Caputo, M.; De Palma, E.; Cerbone, L.; Grosso, F.; La Vecchia, M.; Bona, E.; et al. The Microbiota–Diet–Immunity Axis in Cancer Care: From Prevention to Treatment Modulation and Survivorship. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.-Y.; Zhao, F.-Z.; Li, X.-H.; Zhao, M.-S.; Lv, J.-C.; Shi, M.-J.; Li, J.; Zhou, Z.-Y.; Wang, J.-J.; Song, J. Alteration of pro-carcinogenic gut microbiota is associated with clear cell renal cell carcinoma tumorigenesis. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingdong, W.; Xiang, G.; Yongjun, Q.; Mingshuai, W.; Hao, P. Causal associations between gut microbiota and urological tumors: A two-sample mendelian randomization study. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.J.; Kim, D.S.; Lee, K.W.; Kim, Y.H. The Urinary Microbiome; Axis Crosstalk and Short-Chain Fatty Acid. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieryńska, M.; Szulc-Dąbrowska, L.; Struzik, J.; Mielcarska, M.B.; Gregorczyk-Zboroch, K.P. Integrity of the Intestinal Barrier: The Involvement of Epithelial Cells and Microbiota—A Mutual Relationship. Animals 2022, 12, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panneerselvam, D.; Vaqar, S. Peyer Patches; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.; Zou, J.; Chen, J.; Zhong, X.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. Pattern recognition receptors: Function, regulation and therapeutic potential. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corthésy, B. Role of secretory IgA in infection and maintenance of homeostasis. Autoimmun. Rev. 2013, 12, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitvogel, L.; Ma, Y.; Raoult, D.; Kroemer, G.; Gajewski, T.F. The microbiome in cancer immunotherapy: Diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies. Science 2018, 359, 1366–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, M.; Kolodziejczyk, A.A.; Thaiss, C.A.; Elinav, E. Dysbiosis and the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrand-Rosenberg, S.; Fenselau, C. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells: Immune-Suppressive Cells That Impair Antitumor Immunity and Are Sculpted by Their Environment. J. Immunol. 2018, 200, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ma, C.; Duan, Y.; Heinrich, B.; Rosato, U.; Diggs, L.P.; Ma, L.; Roy, S.; Fu, Q.; Brown, Z.J.; et al. Gut Microbiome Directs Hepatocytes to Recruit MDSCs and Promote Cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2020, 11, 1248–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanoue, T.; Morita, S.; Plichta, D.R.; Skelly, A.N.; Suda, W.; Sugiura, Y.; Narushima, S.; Vlamakis, H.; Motoo, I.; Sugita, K.; et al. A defined commensal consortium elicits CD8 T cells and anti-cancer immunity. Nature 2019, 565, 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskarth, D.A.; Fan, S.; Highton, A.J.; Kemp, R.A. The microbial metabolite butyrate enhances the effector and memory functions of murine CD8+ T cells and improves anti-tumor activity. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1577906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luu, M.; Weigand, K.; Wedi, F.; Breidenbend, C.; Leister, H.; Pautz, S.; Adhikary, T.; Visekruna, A. Regulation of the effector function of CD8+ T cells by gut microbiota-derived metabolite butyrate. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furusawa, Y.; Obata, Y.; Fukuda, S.; Endo, T.A.; Nakato, G.; Takahashi, D.; Nakanishi, Y.; Uetake, C.; Kato, K.; Kato, T.; et al. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature 2013, 504, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tian, R.; Sun, C.; Guo, Y.; Dong, L.; Li, Y.; Song, X. Microbial metabolites are involved in tumorigenesis and development by regulating immune responses. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1290414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Lou, X. Interplay between bile acids, gut microbiota, and the tumor immune microenvironment: Mechanistic insights and therapeutic strategies. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1638352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varanasi, S.K.; Chen, D.; Liu, Y.; Johnson, M.A.; Miller, C.M.; Ganguly, S.; Lande, K.; LaPorta, M.A.; Hoffmann, F.A.; Mann, T.H.; et al. Bile acid synthesis impedes tumor-specific T cell responses during liver cancer. Science 2025, 387, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Wang, Z.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jin, H.; Xu, F.; Wang, X.; Xie, C.; et al. Tryptophan Metabolite Indole-3-Aldehyde Induces AhR and c-MYC Degradation to Promote Tumor Immunogenicity. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e09533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Su, W.; Wang, G.; Wang, Z. The Kynurenine Pathway and Indole Pathway in Tryptophan Metabolism Influence Tumor Progression. Cancer Med. 2025, 14, e70703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.K.; Laursen, M.F.; Brinck, J.E.; Rybtke, M.L.; Hjørne, A.P.; Procházková, N.; Pedersen, M.; Roager, H.M.; Licht, T.R. Dietary fibre directs microbial tryptophan metabolism via metabolic interactions in the gut microbiota. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 1964–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Ren, B.; Ding, C.; Du, C.; Cao, Z.; Yang, G.; Huang, H.; Zhang, T. Polyamines in pancreatic cancer: Reshaping the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. Cancer Lett. 2025, 633, 218016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, G.; Chen, M.; Liao, W.; Fu, L.; Lin, M.; Gui, C.; Cen, J.; Lu, J.; Chen, Z.; Wei, J.; et al. PABPC1L Induces IDO1 to Promote Tryptophan Metabolism and Immune Suppression in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 1659–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bari, S.; Sarfraz, H.; Darwin, A.; Chahoud, J.; Muzaffar, J.; Fishman, M.N.; Jain, R.K.; George, D.J.; Armstrong, A.J.; Chadha, J.; et al. Microbial metabolism of tryptophan is associated with resistance to immune checkpoint (ICB) therapy in renal cell cancer (RCC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 4564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Beltran, A.; Cookson, M.S.; Guercio, B.J.; Cheng, L. Advances in diagnosis and treatment of bladder cancer. BMJ 2024, 384, e076743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, N.D.; Powles, T.B.; Bedke, J.; Galsky, M.D.; Redorta, J.P.; Ku, J.H.; Kretkowski, M.; Xylinas, E.; Alekseev, B.; Ye, D.; et al. Sasanlimab plus BCG in BCG-naive, high-risk non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: The randomized phase 3 CREST trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 2806–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Santis, M.; Redorta, J.P.; Nishiyama, H.; Krawczyński, M.; Seyitkuliev, A.; Novikov, A.; Guerrero-Ramos, F.; Zukov, R.; Kato, M.; Kawahara, T.; et al. Durvalumab in combination with BCG for BCG-naive, high-risk, non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (POTOMAC): Final analysis of a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roupret, M.; Bertaut, A.; Pignot, G.; Neuzillet, Y.; Houede, N.; Mathieu, R.; Corbel, L.; Besson, D.; Seisen, T.; Jaffrelot, L.; et al. ALBAN (GETUG-AFU 37): A phase 3, randomized, open-label, international trial of intravenous atezolizumab and intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) versus BCG alone in BCG-naive high-risk, non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC). Ann. Oncol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukavina, L.; Isali, I.; Ginwala, R.; Sindhani, M.; Calaway, A.; Magee, D.; Miron, B.; Correa, A.; Kutikov, A.; Zibelman, M.; et al. Global Meta-analysis of Urine Microbiome: Colonization of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon–degrading Bacteria Among Bladder Cancer Patients. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2023, 6, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgormus, Y.; Okuyan, O.; Dumur, S.; Sayili, U.; Uzun, H. Evaluation of new generation systemic immune-inflammation markers to predict urine culture growth in urinary tract infection in children. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1201368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, J.S.; Cox, M.A.; Zajac, A.J. T-Cell Exhaustion: Characteristics, Causes and Conversion. Immunology 2010, 129, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vétizou, M.; Pitt, J.M.; Daillère, R.; Lepage, P.; Waldschmitt, N.; Flament, C.; Rusakiewicz, S.; Routy, B.; Roberti, M.P.; Duong, C.P.M.; et al. Anticancer immunotherapy by CTLA-4 blockade relies on the gut microbiota. Science 2015, 350, 1079–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Shah, K. The Potential of the Gut Microbiome to Reshape the Cancer Therapy Paradigm. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 1059–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Liu, B.; Feng, S.; He, Y.; Tang, C.; Chen, P.; Wang, X.; Wang, K. A Large Genetic Causal Analysis of the Gut Microbiota and Urological Cancers: A Bidirectional Mendelian Randomization Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukavina, L.; Calaway, A.; Isali, I.; Prunty, M.; Sindhani, M.; Ghannoum, M.; Retuerto, M.; MacLennan, G.; Markt, S.; Ponsky, L.; et al. MP56-10 CHARACTERIZATION AND FUNCTIONAL ANALYSIS OF MICROBIOME IN BLADDER CANCER. J. Urol. 2022, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pederzoli, F.; Riba, M.; Venegoni, C.; Marandino, L.; Bandini, M.; Alchera, E.; Locatelli, I.; Raggi, D.; Giannatempo, P.; Provero, P.; et al. Stool Microbiome Signature Associated with Response to Neoadjuvant Pembrolizumab in Patients with Muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2024, 85, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, S.K.; Li, S.M.; Wu, X.; Qin, H.; Kortylewski, M.; Hsu, J.; Carmichael, C.; Frankel, P. Stool Bacteriomic Profiling in Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Receiving Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor–Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 5286–5293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, M.; Oda, Y.; Owari, T.; Iida, K.; Ohnishi, S.; Fujii, T.; Nishimura, N.; Miyamoto, T.; Shimizu, T.; Ohnishi, K.; et al. Probiotics enhances anti-tumor immune response induced by gemcitabine plus cisplatin chemotherapy for urothelial cancer. Cancer Sci. 2022, 114, 1118–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derosa, L.; Iebba, V.; Silva, C.A.C.; Piccinno, G.; Wu, G.; Lordello, L.; Routy, B.; Zhao, N.; Thelemaque, C.; Birebent, R.; et al. Custom scoring based on ecological topology of gut microbiota associated with cancer immunotherapy outcome. Cell 2024, 187, 3373–3389.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nearing, J.T.; Douglas, G.M.; Hayes, M.G.; MacDonald, J.; Desai, D.K.; Allward, N.; Jones, C.M.A.; Wright, R.J.; Dhanani, A.S.; Comeau, A.M.; et al. Microbiome differential abundance methods produce different results across 38 datasets. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, M.; Nagatomo, R.; Doi, K.; Shimizu, J.; Baba, K.; Saito, T.; Matsumoto, S.; Inoue, K.; Muto, M. Association of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in the Gut Microbiome With Clinical Response to Treatment With Nivolumab or Pembrolizumab in Patients With Solid Cancer Tumors. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e202895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Vicente, R.; García, A.R.; Ancos-Pintado, R.; Barea, A.A.; Ortega-Hernandez, A.; Bragado-Garcia, I.; Castellano, E.; Ortiz-Ruiz, A.; Navarro-Aguadero, M.A.; Modrego, J.; et al. Enhancing CAR-T Cell Therapy for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma through Gut Microbiota and Butyrate. Blood 2024, 144, 3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, K.; Liu, G.; Wu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Xu, M.; Lu, L.; Li, P. Microbial metabolite butyrate promotes anti-PD-1 antitumor efficacy by modulating T cell receptor signaling of cytotoxic CD8 T cell. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2249143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luu, M.; Riester, Z.; Baldrich, A.; Reichardt, N.; Yuille, S.; Busetti, A.; Klein, M.; Wempe, A.; Leister, H.; Raifer, H.; et al. Microbial short-chain fatty acids modulate CD8+ T cell responses and improve adoptive immunotherapy for cancer. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.K.; Tran, B.; Haanen, J.B.; Hurwitz, M.E.; Sacher, A.; Tannir, N.M.; Budde, L.E.; Harrison, S.J.; Klobuch, S.; Patel, S.S.; et al. CD70-Targeted Allogeneic CAR T-Cell Therapy for Advanced Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2024, 14, 1176–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srour, S.A.; Chahoud, J.; Drakaki, A.; Curti, B.D.; Gibney, G.T.; Pal, S.K.; Tang, L.; Charmsaz, S.; Atwell, J.; Robbins, P.B.; et al. ALLO-316 in advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC): Updated results from the phase 1 TRAVERSE study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 4508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunewald, C.M.; Haist, C.; König, C.; Petzsch, P.; Bister, A.; Nößner, E.; Wiek, C.; Scheckenbach, K.; Köhrer, K.; Niegisch, G.; et al. Epigenetic Priming of Bladder Cancer Cells With Decitabine Increases Cytotoxicity of Human EGFR and CD44v6 CAR Engineered T-Cells. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panebianco, C.; Villani, A.; Pisati, F.; Orsenigo, F.; Ulaszewska, M.; Latiano, T.P.; Potenza, A.; Andolfo, A.; Terracciano, F.; Tripodo, C.; et al. Butyrate, a postbiotic of intestinal bacteria, affects pancreatic cancer and gemcitabine response in in vitro and in vivo models. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 151, 113163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derosa, L.; Hellmann, M.D.; Spaziano, M.; Halpenny, D.; Fidelle, M.; Rizvi, H.; Long, N.; Plodkowski, A.J.; Arbour, K.C.; Chaft, J.E.; et al. Negative association of antibiotics on clinical activity of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced renal cell and non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 1437–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkrief, A.; DeRosa, L.; Kroemer, G.; Zitvogel, L.; Routy, B. The negative impact of antibiotics on outcomes in cancer patients treated with immunotherapy: A new independent prognostic factor? Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1572–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fidelle, M.; Rauber, C.; Silva, C.A.C.; Tian, A.-L.; Lahmar, I.; de La Varende, A.-L.M.; Zhao, L.; Thelemaque, C.; Lebhar, I.; Messaoudene, M.; et al. A microbiota-modulated checkpoint directs immunosuppressive intestinal T cells into cancers. Science 2023, 380, eabo2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespin, A.; Le Bescop, C.; de Gunzburg, J.; Vitry, F.; Zalcman, G.; Cervesi, J.; Bandinelli, P.-A. A systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the impact of antibiotic use on the clinical outcomes of cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1075593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizman, N.; Meza, L.; Bergerot, P.; Alcantara, M.; Dorff, T.; Lyou, Y.; Frankel, P.; Cui, Y.; Mira, V.; Llamas, M.; et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab with or without live bacterial supplementation in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: A randomized phase 1 trial. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, H.; Dizman, N.; Meza, L.; Malhotra, J.; Li, X.; Dorff, T.; Frankel, P.; Llamas-Quitiquit, M.; Hsu, J.; Zengin, Z.B.; et al. Cabozantinib and nivolumab with or without live bacterial supplementation in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: A randomized phase 1 trial. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2576–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccarese, C.; Porcari, S.; Buti, S.; Fornarini, G.; Primi, F.; Giudice, G.; Damassi, A.; Berrios, J.G.; Stumbo, L.; Arduini, D.; et al. LBA77 Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) versus placebo in patients receiving pembrolizumab plus axitinib for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Preliminary results of the randomized phase II TACITO trial. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, S1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruch, E.N.; Youngster, I.; Ben-Betzalel, G.; Ortenberg, R.; Lahat, A.; Katz, L.; Adler, K.; Dick-Necula, D.; Raskin, S.; Bloch, N.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplant promotes response in immunotherapy-refractory melanoma patients. Science 2020, 371, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davar, D.; Dzutsev, A.K.; McCulloch, J.A.; Rodrigues, R.R.; Chauvin, J.-M.; Morrison, R.M.; Deblasio, R.N.; Menna, C.; Ding, Q.; Pagliano, O.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplant overcomes resistance to anti–PD-1 therapy in melanoma patients. Science 2021, 371, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routy, B.; Lenehan, J.G.; Miller, W.H.; Jamal, R.; Messaoudene, M.; Daisley, B.A.; Hes, C.; Al, K.F.; Martinez-Gili, L.; Punčochář, M.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation plus anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in advanced melanoma: A phase I trial. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 2121–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkrief, A.; Duttagupta, S.; Jamal, R.; Marcoux, N.; Desilets, A.; Messaoudene, M.; Mihalcioiu, C.; Durand, S.; Tehfe, M.; Blais, N.; et al. 1068P Phase II trial of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) plus immune checkpoint inhibition (ICI) in advanced non-small cell lung cancer and cutaneous melanoma (FMT-LUMINate). Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, S707–S708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, G.; Kim, S.; Cho, B.; Kim, S.-Y.; Do, E.-J.; Bae, D.-J.; Kim, S.; Kweon, M.-N.; Song, J.S.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation improves anti-PD-1 inhibitor efficacy in unresectable or metastatic solid cancers refractory to anti-PD-1 inhibitor. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 1380–1393.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Lei, J.; Ke, S.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, J.; Tang, Z.; Wang, L.; Ren, Y.; Alnaggar, M.; Qiu, H.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation plus tislelizumab and fruquintinib in refractory microsatellite stable metastatic colorectal cancer: An open-label, single-arm, phase II trial (RENMIN-215). eClinicalMedicine 2023, 66, 102315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swog: Protocol Tracking Reports. Available online: https://members.swog.org/protocoldevelopmentreports/Dashboard.asp?k=6Fgsf5fadagsj5hhhshsf55gffa (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Glitza, I.C.; Seo, Y.D.; Spencer, C.N.; Wortman, J.R.; Burton, E.M.; Alayli, F.A.; Loo, C.P.; Gautam, S.; Damania, A.; Densmore, J.; et al. Randomized Placebo-Controlled, Biomarker-Stratified Phase Ib Microbiome Modulation in Melanoma: Impact of Antibiotic Preconditioning on Microbiome and Immunity. Cancer Discov. 2024, 14, 1161–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Chang, H.-W.; Yan, D.; Lee, K.M.; Ucmak, D.; Wong, K.; Abrouk, M.; Farahnik, B.; Nakamura, M.; Zhu, T.H.; et al. Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health. J. Transl. Med. 2017, 15, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holscher, H.D. Dietary fiber and prebiotics and the gastrointestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes 2017, 8, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somodi, C.; Dora, D.; Horváth, M.; Szegvari, G.; Lohinai, Z. Gut microbiome changes and cancer immunotherapy outcomes associated with dietary interventions: A systematic review of preclinical and clinical evidence. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guercio, B.J.; Ratna, N.; Gavrilov, D.; Duzgol, C.; Akhlaq, M.; Teo, M.Y.; Regazzi, A.M.; Kotecha, R.R.; A Funt, S.; Aggen, D.H.; et al. Associations of diet with survival of patients (pts) with metastatic cancer of the urothelium (mUC) and renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) on immune checkpoint blockade (ICB). J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolte, L.A.; Lee, K.A.; Björk, J.R.; Leeming, E.R.; Campmans-Kuijpers, M.J.E.; de Haan, J.J.; Vila, A.V.; Maltez-Thomas, A.; Segata, N.; Board, R.; et al. Association of a Mediterranean Diet With Outcomes for Patients Treated With Immune Checkpoint Blockade for Advanced Melanoma. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 705–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farias, R.M.; Jiang, Y.; Levy, E.J.; Hwang, C.; Wang, J.; Burton, E.M.; Cohen, L.; Ajami, N.; Wargo, J.A.; Daniel, C.R.; et al. Diet and Immune Effects Trial (DIET)- a randomized, double-blinded dietary intervention study in patients with melanoma receiving immunotherapy. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Dizman, N.; Jiang, Y.; Robert, M.; Farias, R.; Levy, E.J.; Hwang, C.; Wang, J.; Wong, M.K.; Patel, S.P.; et al. Clinical outcomes of the DIET study: A randomized controlled phase 2 trial of a high fiber diet intervention (HFDI) in patients with melanoma receiving immune checkpoint blockade (ICB). J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 9511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messaoudene, M.; Pidgeon, R.; Richard, C.; Ponce, M.; Diop, K.; Benlaifaoui, M.; Nolin-Lapalme, A.; Cauchois, F.; Malo, J.; Belkaid, W.; et al. A Natural Polyphenol Exerts Antitumor Activity and Circumvents Anti–PD-1 Resistance through Effects on the Gut Microbiota. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 1070–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, S.A.; Elkrief, A.; Capella, M.P.; Miller, W.H. Two Cases of Durable and Deep Responses to Immune Checkpoint Inhibition-Refractory Metastatic Melanoma after Addition of Camu Camu Prebiotic. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 7852–7859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrere, G.; Alou, M.T.; Liu, P.; Goubet, A.-G.; Fidelle, M.; Kepp, O.; Durand, S.; Iebba, V.; Fluckiger, A.; Daillère, R.; et al. Ketogenic diet and ketone bodies enhance the anticancer effects of PD-1 blockade. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab with or Without Bacterial Supplementation in Metastatic Renal Carcinoma: A Randomized Phase 1 Trial | Cabozantinib and Nivolumab with or Without Live Bacterial Supplementation in Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Randomized Phase 1 Trial | LBA77 Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) Versus Placebo in Patients Receiving Pembrolizumab Plus Axitinib for Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma: Preliminary Results of the Randomized Phase 2 TACITO Trial | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier | NCT03829111 | NCT05122546 | NCT04758507 |

| Study Citation | Dizman, N., Meza, L., Bergerot, P. et al. Nat Med 28, 704–712 (2022). [100] | Ebrahimi H, Dizman N, Meza L, et al. Nat Med. 2024;30(9):2576–2585. [101] | Ciccarese, C. et al. LBA77, Annals of Oncology, Volume 35, Supplement 2, 2024, Page S1264, [102] |

| Patient Population | n = 29 Metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC), treatment-native | n = 30 Advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC), treatment native | n = 50 Metastatic renal cell carcinoma |

| Treatment Regimen | Nivolumab + ipilimumab | Cabozantinib + Nivolumab | Axitinib + Pembrolizumab |

| Microbiome Intervention | Probiotic CBM588 (Clostridium butyricum) | Probiotic CBM588 (Clostridium butyricum) | FMT |

| Primary Endpoint | Effect of CBM588 on relative abundance of gut microbial populations and specifically Bifidobacterium spp. | Change in the relative abundance of Bifidobacterium spp. | Increase of ≥ 20% in the rate of patients with no-disease progression at 1-year (1-year PFS) with FMT vs. without |

| Result of primary analysis | Negative No significant from baseline to week 12 in experimental arm or control (p = 0.304, p = 0.461) | Negative No significant from baseline to week 13 in experimental arm or control (p = 0.95, p = 0.39) | Positive Axitinib + Pembrolizumab with FMT (66.7% vs. 35%, p = 0.036) |

| Key Secondary Clinical Efficacy Endpoints | Comparing experimental arm (nivolumab + ipilimumab + CBM588) to control (nivolumab + ipilimumab): PFS (12.7 vs. 2.5 months; HR 0.15, 95% CI 0.05–0.47, p = 0.001) ORR (58% vs. 20%, p = 0.06) Reduction in tumor target lesions (74% vs. 50%) Disease control (79% vs. 40%) | Comparing experimental arm to control: PFS at 6 months (84% vs. 60%) ORR (74% vs. 20%, p = 0.01) Reduction in tumor target lesions (89% vs. 80%) | Comparing experimental arm to control: Median PFS was 14.2 months (95% CI, 0.9–27.6) vs. 9.2 months (95% CI, 3.0–15.4) ORR (54% vs. 28%) |

| Therapy | Phase | Patient Population | Trial Identifier | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interventional Trials | ||||

| Probiotic/Prebiotic | ||||

| Cabozantinib + Nivolumab with CBM588 | 1 | Advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) | NCT05122546 | Active, not recruiting |

| Pembrolizumab with CBM588 | 2 | RCC T2-4 any grade, N0M0; T TxNxM0-1 | NCT07037004 | Not yet recruiting |

| Nivolumab + ipilimumab with CBM588 | 1 | Advanced or metastatic RCC | NCT06399419 | Recruiting |

| Nivolumab with BMC128 | 1 | mRCC or clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) | NCT05354102 | Active, not recruiting |

| Fecal Microbiota Transplant | ||||

| Nivolumab + ipilimumab with FMT (PERFORM) | 1 | Advanced or mRCC | NCT04163289 | Active, not recruiting |

| Dietary Interventions | ||||

| Nivolumab + ipilimumab or single agent ipilimumab/nivolumab/pembrolizumab with ketogenic diet | 1 | Metastatic melanoma or mRCC | NCT06391099 | Recruiting |

| Nivolumab + ipilimumab/relatimab or single agent ipilimumab/nivolumab/pembrolizumab with ketogenic diet | 1/2 | Melanoma or ccRCC or mRCC | NCT06896552 | Not yet recruiting |

| Nivolumab + ipilimumab with inulin gel | 1/2 | Advanced or mRCC | NCT06866262 | Recruiting |

| Observational Trials | ||||

| ICIs (single agent or combination) effect on gut microbiota (PARADIGM) | NSCLC, malignant melanoma, RCC, TNBC; any stage | NCT05037825 | Recruiting | |

| Investigate how the microbiome correlates with efficacy and toxicity of ICIs) in patients with advanced cancer | Advanced melanoma, RCC, or NSCLC | NCT04107168 | Unknown Status | |

| Establish the microbiota composition as a predictive tool for the response to the intravesical immunotherapy with BCG or Gem/Dox or MMC | Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) | NCT06675656 | Not yet recruiting | |

| Investigating differences in the bladder microbiome in urothelial cacinoma | Urothelial Carcinoma | NCT06992986 | Recruiting | |

| Microbiota profiling in urine and bladder tissue of male healthy individuals and patients with bladder cancer | Bladder Cancer | NCT06289283 | Active, not recruiting |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Winslow, T.B.; Gupta, S.; Vaddaraju, V.S.; Guercio, B.J.; Sahasrabudhe, D.M. The Microbiome and Genitourinary Cancers: A New Frontier. Cancers 2025, 17, 3606. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223606

Winslow TB, Gupta S, Vaddaraju VS, Guercio BJ, Sahasrabudhe DM. The Microbiome and Genitourinary Cancers: A New Frontier. Cancers. 2025; 17(22):3606. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223606

Chicago/Turabian StyleWinslow, Timothy B., Sophia Gupta, Vedha Sai Vaddaraju, Brendan J. Guercio, and Deepak M. Sahasrabudhe. 2025. "The Microbiome and Genitourinary Cancers: A New Frontier" Cancers 17, no. 22: 3606. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223606

APA StyleWinslow, T. B., Gupta, S., Vaddaraju, V. S., Guercio, B. J., & Sahasrabudhe, D. M. (2025). The Microbiome and Genitourinary Cancers: A New Frontier. Cancers, 17(22), 3606. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17223606