Impact of Pain Education on Pain Relief in Oncological Patients: A Narrative Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Narrative Review Checklist

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Quality Assessment

3. Results

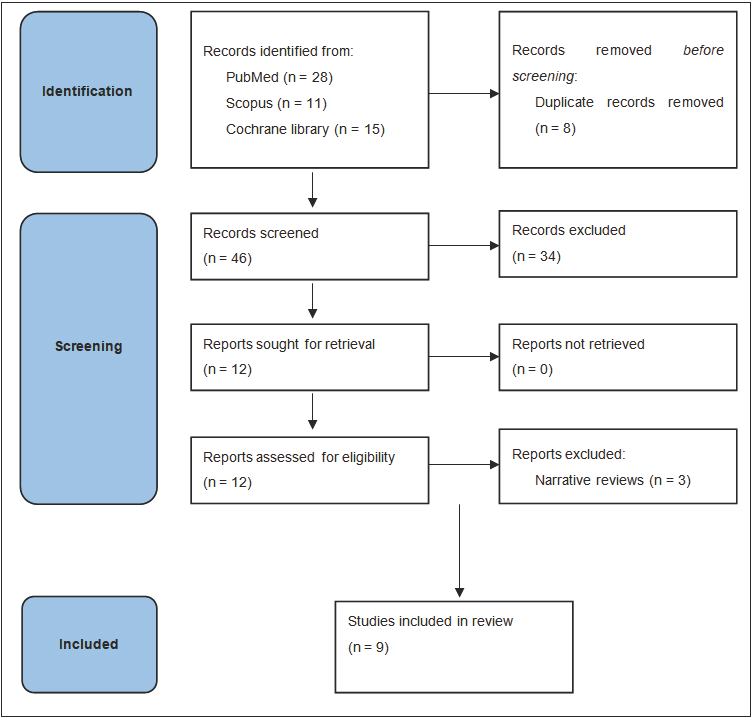

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Quality Assessment

3.3. Effectiveness of Pain Education on Pain Relief

3.3.1. Systematic Reviews

3.3.2. Meta-Analyses

3.3.3. Other Effects of Pain Education

3.3.4. Effectiveness of Different Pain Education Models

4. Discussion

4.1. Narrative

4.2. Heterogeneity of Intervention Characteristics and Outcomes

4.3. Influence of Comparator Selection

4.4. Methodological Quality of the Evidence Base

4.5. Clinical Implications

4.6. Limitations and Gaps in Current Knowledge

4.7. Future Research Directions

5. Summary

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Snijders, R.A.H.; Brom, L.; Theunissen, M.; Everdingen, M.H.J.v.D.B.-V. Update on Prevalence of Pain in Patients with Cancer 2022: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2023, 15, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, J.H. Overcoming barriers in cancer pain management. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1727–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, R.; Møldrup, C.; Christrup, L.; Sjøgren, P. Patient-related barriers to cancer pain management: A systematic exploratory review. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2009, 23, 190–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miaskowski, C.; Dodd, M.J.; West, C.; Paul, S.M.; Tripathy, D.; Koo, P.; Schumacher, K. Lack of Adherence With the Analgesic Regimen: A Significant Barrier to Effective Cancer Pain Management. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001, 19, 4275–4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrell, B.R.; Rivera, L.M. Cancer pain education for patients. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 1997, 13, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelf, J.H.; Agre, P.; Axelrod, A.; Cheney, L.; Cole, D.D.; Conrad, K.; Hooper, S.; Liu, I.; Mercurio, A.; Stepan, K.; et al. Cancer-related patient education: An overview of the last decade of evaluation and research. Oncol. Nurs. Soc. 2001, 28, 1139–1147. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, M.Y.; Pisu, M.; Kvale, E.A.; Johns, S.A. Developing Effective Cancer Pain Education Programs. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2012, 16, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, P.; Maunsell, E.; Labbé, J.; Dorval, M. Educational Interventions to Improve Cancer Pain Control: A Systematic Review. J. Palliat. Med. 2001, 4, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, G.R.; Morrison, R.S. Pain Management in Hospitalized Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 1792–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenmenger, W.H.; Smitt, P.A.S.; van Dooren, S.; Stoter, G.; van der Rijt, C.C. A systematic review on barriers hindering adequate cancer pain management and interventions to reduce them: A critical appraisal. Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 1370–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, C.; Lui, L.Y.; So, W.K. Do educational interventions improve cancer patients’ quality of life and reduce pain intensity? Quantitative systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2011, 68, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koller, A.; Miaskowski, C.; De Geest, S.; Opitz, O.; Spichiger, E. A systematic evaluation of content, structure, and efficacy of in-terventions to improve patients’ self-management of cancer pain. J. Pain Symptom. Manag. 2012, 44, 264–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldenmenger, W.H.; Geerling, J.I.; Mostovaya, I.; Vissers, K.C.; de Graeff, A.; Reyners, A.K.; van der Linden, Y.M. A systematic review of the effectiveness of patient-based educational interventions to improve cancer-related pain. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2018, 63, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, M.I.; Bagnall, A.-M.; Closs, J.S. How effective are patient-based educational interventions in the management of cancer pain? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain 2009, 143, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, G.G.; Olivo, S.A.; Biondo, P.D.; Stiles, C.R.; Yurtseven, Ö.; Fainsinger, R.L.; Hagen, N.A. Effectiveness of Knowledge Translation Interventions to Improve Cancer Pain Management. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2011, 41, 915–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jho, H.J.; Myung, S.K.; Chang, Y.J.; Kim, D.H.; Ko, D.H. Efficacy of pain education in cancer patients: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Support Care Cancer 2013, 21, 1963–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baethge, C.; Goldbeck-Wood, S.; Mertens, S. SANRA—A scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2019, 26, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Schneider, M.; Smith, G.D. Meta-analysis Spurious precision? Meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ 1998, 316, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerling, J.I.; van der Linden, Y.M.; Raijmakers, N.J.; Vermeulen, K.M.; Mul, V.E.; de Nijs, E.J.; Westhoff, P.G.; de Bock, G.H.; de Graeff, A.; Reyners, A.K. Randomized controlled study of pain education in patients receiving radiotherapy for painful bone metastases. Radiother. Oncol. 2023, 185, 109687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotman, D.J.; Bartels, M.M.T.J.; Ferrer, C.J.; Bos, C.; Bartels, L.W.; Boomsma, M.F.; Phernambucq, E.C.J.; Nijholt, I.M.; Morganti, A.G.; Siepe, G.; et al. Focused Ultrasound and RadioTHERapy for non-invasive palliative pain treatment in patients with bone metastasis: A study protocol for the three armed randomized controlled FURTHER trial. Trials 2022, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieretti, S.; Di Giannuario, A.; Di Giovannandrea, R.; Marzoli, F.; Piccaro, G.; Minosi, P.; Aloisi, A.M. Gender differences in pain and its relief. Ann. Dell’istituto Super. Di Sanita 2016, 52, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alodhayani, A.; Almutairi, K.M.; Vinluan, J.M.; Alsadhan, N.; Almigbal, T.H.; Alonazi, W.B.; Batais, M.A. Gender Difference in Pain Management Among Adult Cancer Patients in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Assessment. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scirocco, E.; Cellini, F.; Donati, C.M.; Capuccini, J.; Rossi, R.; Buwenge, M.; Montanari, L.; Maltoni, M.; Morganti, A.G. Improving the Integration between Palliative Radiotherapy and Supportive Care: A Narrative Review. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference (Author, Year) | Objective of Review | Participants/Population | No. of Studies Included | Study Design Focus | Pain Education Intervention | Pain Intensity Concept/Tool |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allard et al., 2001 [8] | Evaluate the effect of a nurse-delivered educational intervention on cancer pain management. | Cancer patients receiving nurse-based PE | Systematic review (2 RCTs and 6 nRCTs) | RCTs | Single vs. multiple home nurse visits | NRS (self-reported pain) |

| Goldberg et al., 2007 [9] | Assess effectiveness of educational interventions in improving cancer pain outcomes. | Cancer patients (various settings) | Systematic review (2 RCTs) | RCTs and non-RCTs | Various formats: printed, face-to-face, multimedia | Varied, often NRS or VAS |

| Oldenmenger et al., 2009 [10] | Identify barriers hindering adequate cancer pain management and critically review interventions to overcome these barriers. | Cancer patients (various clinical settings, mixed inpatient/outpatient) | Systematic review (10 RCTs) | Mixed methods (RCT and non-RCTs) | Patient education programs (single to multiple sessions) | Various: average, current, worst pain (often NRS 0-10) |

| Ling et al., 2012 [11] | Evaluate effects of psychoeducational interventions in cancer pain. | Cancer patients (all stages) | Systematic review (4 RCTs) | RCTs | Psychoeducational models | Average pain via NRS |

| Koller et al., 2012 [12] | Assess efficacy of various pain management education strategies. | Cancer patients (mixed stages, global) | Systematic review (23 RCTS and 1 nRCT) | RCTs | Structured vs. tailored interventions | NRS/VAS (not consistently defined) |

| Oldenmenger et al., 2018 [13] | Update and expand previous review on pain education in cancer. | Cancer patients receiving PE | Systematic review (26 RCTs) | Mixed | Multimodal pain education | Multiple scales |

| Authors/Year [ref] | Effect of Pain Education on Pain | Other Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Allard et al./2001 [8] |

|

|

| Goldberg et al./2007 [9] |

|

|

| Oldenmenger et al./2009 [10] |

|

|

| Ling et al./2011 [11] |

|

|

| Koller et al./2012 [12] |

|

|

| Oldenmenger et al./2018 [13] |

|

|

| Reference (Author, Year) | Objective of Review | Participants/Population | No. of Studies Included | Study Design Focus | Pain Education Intervention | Pain Intensity Concept/Tool |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bennett et al., 2009 [14] | Quantitatively analyze impact of PE on cancer pain using meta-analysis. | RCTs with cancer patients | Meta-analysis (10 RCTs and 2 nRCTs) | RCTs | PE session vs. control | SMDs from RCTs |

| Cummings et al., 2011 [15] | Review evidence of PE on cancer-related pain intensity. | Cancer patients in RCTs | Meta-analysis (11 RCTs) | RCTs | PE intensity/duration comparisons | SMD, mean difference |

| Jho et al., 2013 [16] | Summarize effectiveness of PE interventions on pain and related outcomes. | Adult cancer patients | Meta-analysis (12 RCTs) | RCTs | General PE strategies | Not standardized across studies |

| Authors/ Year [Ref] | Effect of Pain Education on Pain | Other Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Bennett et al./2009 [14] |

| Medication adherence improved in 1/3 studies. |

| Cummings et al./2011 [15] |

| NR |

| Jho et al./2013 [16] |

| NR |

| Authors/ Year [Ref] | Comparative Results |

|---|---|

| Allard et al./2001 [8] |

|

| Bennett et al./2009 [14] |

|

| Cummings et al./2011 [15] |

|

| Koller et al./2012 [12] |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galietta, E.; Donati, C.M.; Bazzocchi, A.; Sassi, R.; Zamfir, A.A.; Hovenier, R.; Bos, C.; Hendriks, N.; Boomsma, M.F.; Huhtala, M.; et al. Impact of Pain Education on Pain Relief in Oncological Patients: A Narrative Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Cancers 2025, 17, 1683. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17101683

Galietta E, Donati CM, Bazzocchi A, Sassi R, Zamfir AA, Hovenier R, Bos C, Hendriks N, Boomsma MF, Huhtala M, et al. Impact of Pain Education on Pain Relief in Oncological Patients: A Narrative Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Cancers. 2025; 17(10):1683. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17101683

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalietta, Erika, Costanza M. Donati, Alberto Bazzocchi, Rebecca Sassi, Arina A. Zamfir, Renée Hovenier, Clemens Bos, Nikki Hendriks, Martijn F. Boomsma, Mira Huhtala, and et al. 2025. "Impact of Pain Education on Pain Relief in Oncological Patients: A Narrative Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses" Cancers 17, no. 10: 1683. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17101683

APA StyleGalietta, E., Donati, C. M., Bazzocchi, A., Sassi, R., Zamfir, A. A., Hovenier, R., Bos, C., Hendriks, N., Boomsma, M. F., Huhtala, M., Blanco Sequeiros, R., Grüll, H., Ferdinandus, S., Verkooijen, H. M., & Morganti, A. G. (2025). Impact of Pain Education on Pain Relief in Oncological Patients: A Narrative Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Cancers, 17(10), 1683. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17101683