Transfusion-Related Cost and Time Burden Offsets in Patients with Myelofibrosis Treated with Momelotinib in the SIMPLIFY-1 and SIMPLIFY-2 Trials

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Variables: Outcomes and Inputs

2.3. Statistical Analyses of Transfusion Status and Rates in SIMPLIFY-1 and SIMPLIFY-2

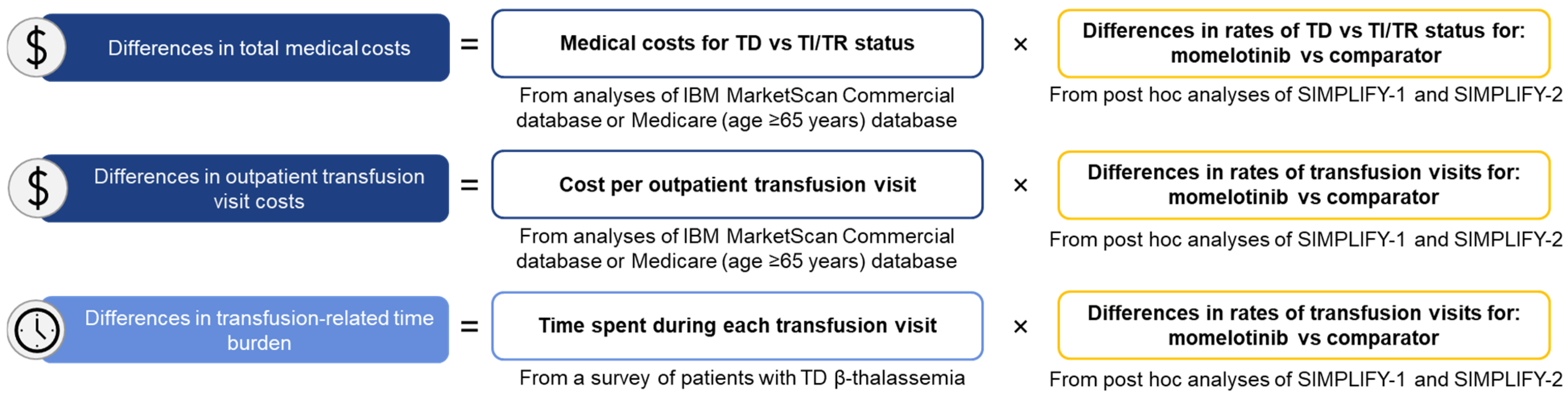

2.4. Calculating Projected Differences in Cost and Time Burden

3. Results

3.1. JAK Inhibitor Naive (SIMPLIFY-1)

3.1.1. Transfusion Status and Rates

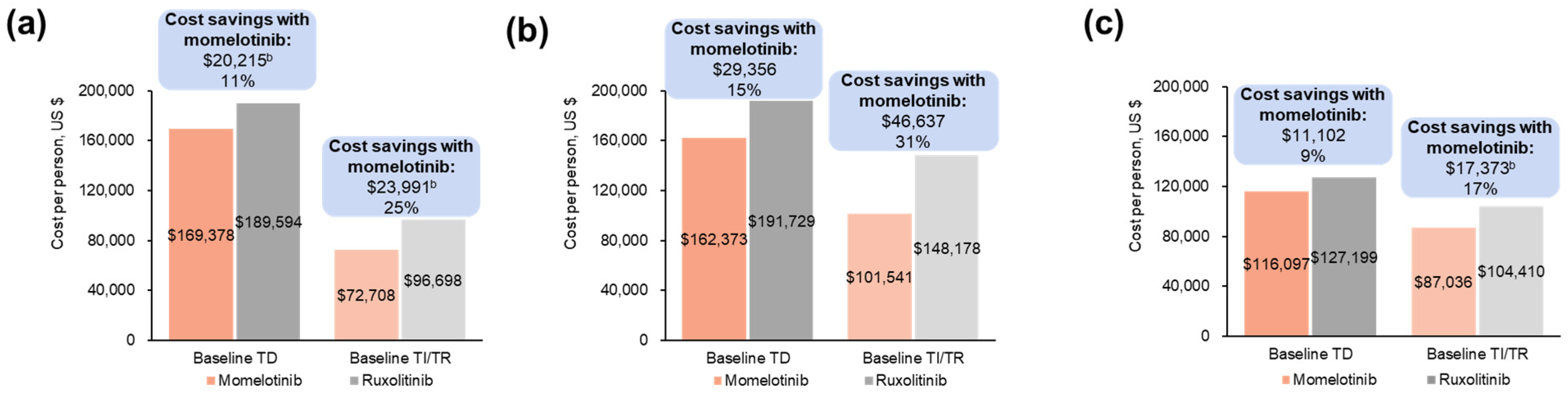

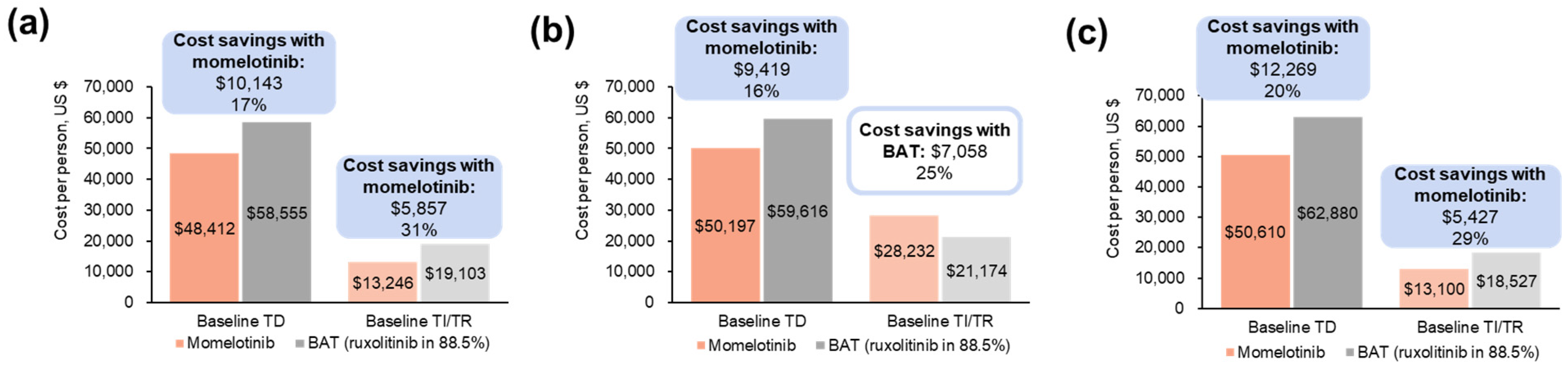

3.1.2. Projected Differences in Total Annual Medical Costs

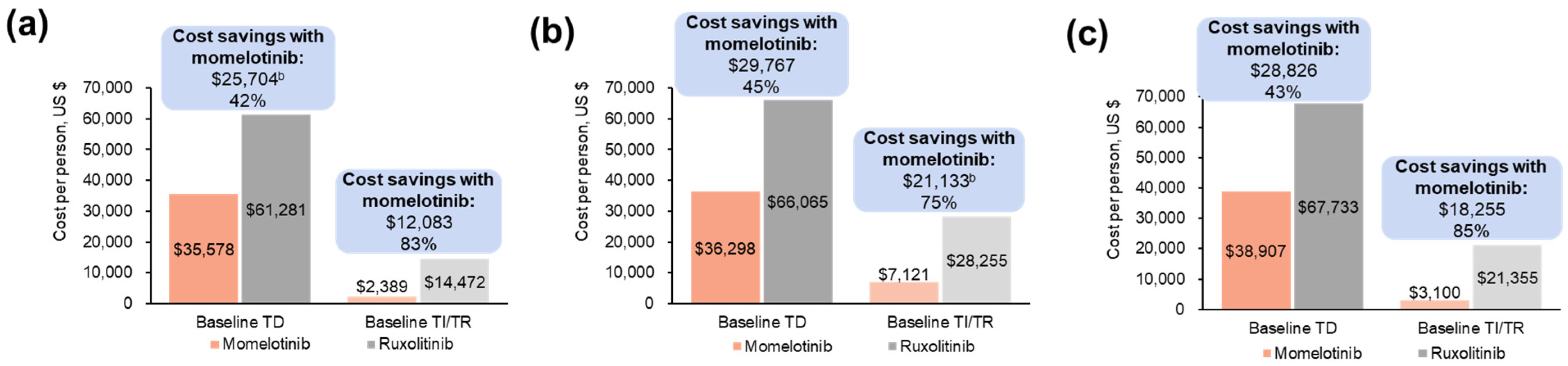

3.1.3. Projected Differences in Annual Outpatient Transfusion Visit Costs

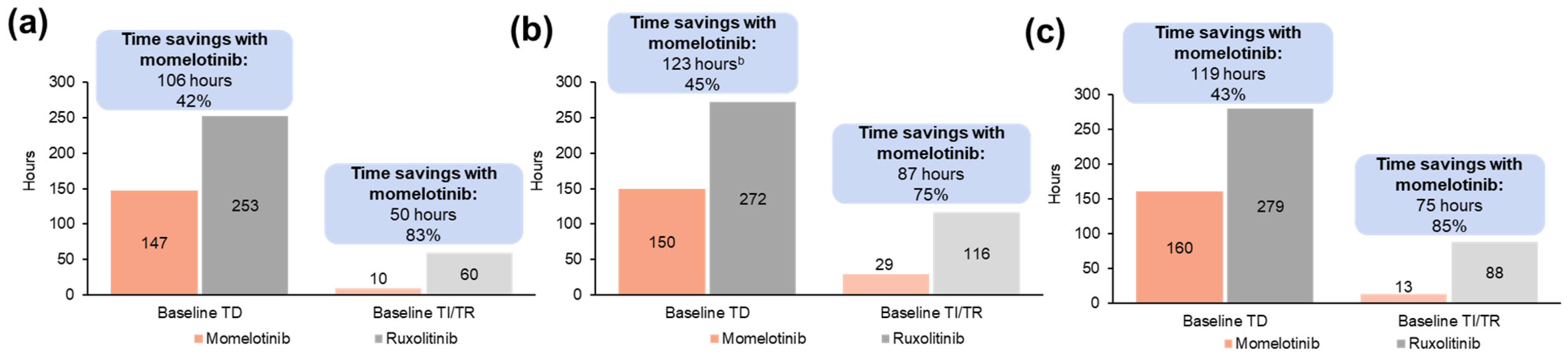

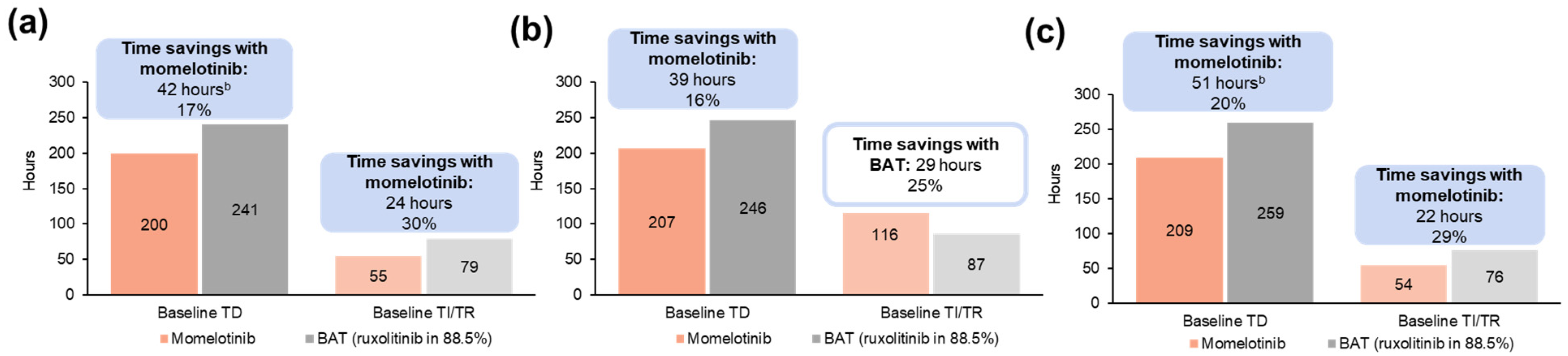

3.1.4. Projected Differences in Annual Transfusion-Related Time Burden for Patients

3.2. JAK Inhibitor-Experienced (SIMPLIFY-2)

3.2.1. Transfusion Status and Rates

3.2.2. Projected Differences in Total Annual Medical Costs

3.2.3. Projected Differences in Annual Outpatient Transfusion Visit Costs

3.2.4. Projected Differences in Annual Transfusion-Related Time Burden for Patients

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tefferi, A. Primary myelofibrosis: 2023 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am. J. Hematol. 2023, 98, 801–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tefferi, A.; Lasho, T.L.; Jimma, T.; Finke, C.M.; Gangat, N.; Vaidya, R.; Begna, K.H.; Al-Kali, A.; Ketterling, R.P.; Hanson, C.A.; et al. One thousand patients with primary myelofibrosis: The Mayo Clinic experience. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2012, 87, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, D.; Kaye, J.A.; Piecoro, L.T.; Brown, J.; Reith, K.; Mughal, T.I.; Sarlis, N.J. Symptom burden and splenomegaly in patients with myelofibrosis in the United States: A retrospective medical record review. Cancer Med. 2013, 2, 889–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naymagon, L.; Mascarenhas, J. Myelofibrosis-related anemia: Current and emerging therapeutic strategies. Hemasphere 2017, 1, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chifotides, H.T.; Bose, P.; Verstovsek, S. Momelotinib: An emerging treatment for myelofibrosis patients with anemia. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elena, C.; Passamonti, F.; Rumi, E.; Malcovati, L.; Arcaini, L.; Boveri, E.; Merli, M.; Pietra, D.; Pascutto, C.; Lazzarino, M. Red blood cell transfusion-dependency implies a poor survival in primary myelofibrosis irrespective of IPSS and DIPSS. Haematologica 2011, 96, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolosi, M.; Mudireddy, M.; Lasho, T.L.; Hanson, C.A.; Ketterling, R.P.; Gangat, N.; Pardanani, A.; Tefferi, A. Sex and degree of severity influence the prognostic impact of anemia in primary myelofibrosis: Analysis based on 1109 consecutive patients. Leukemia 2018, 32, 1254–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tefferi, A.; Hudgens, S.; Mesa, R.; Gale, R.P.; Verstovsek, S.; Passamonti, F.; Cervantes, F.; Rivera, C.; Tencer, T.; Khan, Z.M. Use of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Anemia in persons with myeloproliferative neoplasm-associated myelofibrosis and anemia. Clin. Ther. 2014, 36, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vekeman, F.; Cheng, W.Y.; Sasane, M.; Huynh, L.; Duh, M.S.; Paley, C.; Mesa, R.A. Medical complications, resource utilization and costs in patients with myelofibrosis by frequency of blood transfusion and iron chelation therapy. Leuk. Lymphoma 2015, 56, 2803–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passamonti, F.; Harrison, C.N.; Mesa, R.A.; Kiladjian, J.J.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Verstovsek, S. Anemia in myelofibrosis: Current and emerging treatment options. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2022, 180, 103862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerds, A.T.; Harrison, C.; Thompson, S.; Snopek, F.; Pemmaraju, N. The burden of illness and the incremental burden of transfusion dependence in myelofibrosis in the United States. Poster 1729. In Proceedings of the 64th ASH Annual Meeting & Exposition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–13 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gerds, A.T.; Tkacz, J.; Moore-Schiltz, L.; Schinkel, J.; Phiri, K.; Liu, T.; Gorsh, B. Evaluating estimated health care resource utilization and costs in patients with myelofibrosis based on transfusion status and anemia severity: A retrospective analysis of the Medicare Fee-For-Service claims data. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2024, 30, 1395–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstovsek, S.; Chen, C.C.; Egyed, M.; Ellis, M.; Fox, L.; Goh, Y.T.; Gupta, V.; Harrison, C.; Kiladjian, J.J.; Lazaroiu, M.C.; et al. MOMENTUM: Momelotinib vs danazol in patients with myelofibrosis previously treated with JAKi who are symptomatic and anemic. Future Oncol. 2021, 17, 1449–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.T.; Talpaz, M.; Gerds, A.T.; Gupta, V.; Verstovsek, S.; Mesa, R.; Miller, C.B.; Rivera, C.E.; Fleischman, A.G.; Goel, S.; et al. ACVR1/JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor momelotinib reverses transfusion dependency and suppresses hepcidin in myelofibrosis phase 2 trial. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 4282–4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa, R.A.; Kiladjian, J.J.; Catalano, J.V.; Devos, T.; Egyed, M.; Hellmann, A.; McLornan, D.; Shimoda, K.; Winton, E.F.; Deng, W.; et al. SIMPLIFY-1: A phase III randomized trial of momelotinib versus ruxolitinib in Janus kinase inhibitor-naïve patients with myelofibrosis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 3844–3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C.N.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Platzbecker, U.; Cervantes, F.; Gupta, V.; Lavie, D.; Passamonti, F.; Winton, E.F.; Dong, H.; Kawashima, J.; et al. Momelotinib versus best available therapy in patients with myelofibrosis previously treated with ruxolitinib (SIMPLIFY 2): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2018, 5, e73–e81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstovsek, S.; Gerds, A.T.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Al-Ali, H.K.; Lavie, D.; Kuykendall, A.T.; Grosicki, S.; Iurlo, A.; Goh, Y.T.; Lazaroiu, M.C.; et al. Momelotinib versus danazol in symptomatic patients with anaemia and myelofibrosis (MOMENTUM): Results from an international, double-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet 2023, 401, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GSK. Momelotinib (Ojjaara) Prescribing Information. Available online: https://gskpro.com/content/dam/global/hcpportal/en_US/Prescribing_Information/Ojjaara/pdf/OJJAARA-PI-PIL.PDF (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Knoth, R.L.; Gupta, S.; Perkowski, K.; Costantino, H.; Inyart, B.; Ashka, L.; Clapp, K.; McBride, A. P1741: Examining the burden of illness associated with transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia from the patient’s perspective. Hemasphere 2022, 6, 1622–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoth, R.L.; Gupta, S.; Perkowski, K.; Costantino, H.; Inyart, B.; Ashka, L.; Clapp, K. Understanding the association between red blood cell transfusion utilization and humanistic and economic burden in patients with β-thalassemia from the patients’ perspective. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Oh, S.; Devos, T.; Dubruille, V.; Catalano, J.; Somervaille, T.C.P.; Platzbecker, U.; Giraldo, P.; Kosugi, H.; Sacha, T.; et al. Momelotinib vs. ruxolitinib in myelofibrosis patient subgroups by baseline hemoglobin levels in the SIMPLIFY-1 trial. Leuk. Lymphoma 2024, 65, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.T.; Scott, B.L.; Hunter, A.M.; Palmer, J.M.; Liu, T.; Patel, B.; Zhang, S.; Jones, M.; Ellis, C.E.; Strouse, B.; et al. Clinical outcomes with momelotinib vs ruxolitinib in patients with myelofibrosis and moderate anemia: Subgroup analysis of SIMPLIFY-1. Poster 129. In Proceedings of the 16th International Congress on Myeloproliferative Neoplasms, Brooklyn, NY, USA, 24–25 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, C.N.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Recher, C.; Passamonti, F.; Gerds, A.T.; Hernandez-Boluda, J.C.; Yacoub, A.; Sirhan, S.; Ellis, C.; Patel, B.; et al. Momelotinib versus continued ruxolitinib or best available therapy in JAK inhibitor-experienced patients with myelofibrosis and anemia: Subgroup analysis of SIMPLIFY-2. Adv. Ther. 2024, 41, 3722–3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, E.N.; Platzbecker, U.; Fenaux, P.; Garcia-Manero, G.; LeBlanc, T.W.; Patel, B.J.; Kubasch, A.S.; Sekeres, M.A. Targeting health-related quality of life in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes—Current knowledge and lessons to be learned. Blood Rev. 2021, 50, 100851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa, R.; Miller, C.B.; Thyne, M.; Mangan, J.; Goldberger, S.; Fazal, S.; Ma, X.; Wilson, W.; Paranagama, D.C.; Dubinski, D.G.; et al. Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) have a significant impact on patients’ overall health and productivity: The MPN Landmark survey. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLornan, D.P.; Saunders, C.J.; Harrison, C.N. Considerations to comprehensive care for the older individual with myelofibrosis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Haematol. 2022, 35, 101371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa, R.; Palandri, F.; Verstovsek, S.; Masarova, L.; Harrison, C.; Mazerolle, F.; Gorsh, B.; M’hari, M.; Wang, Z.; Ellis, C.; et al. Impact of transfusion burden on health-related quality of life and functioning in patients with myelofibrosis: Post hoc analysis of SIMPLIFY-1 and -2. Poster 7066. In Proceedings of the 2023 ASCO Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, USA, 2–6 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Masarova, L.; Verstovsek, S.; Liu, T.; Rao, S.; Sajeev, G.; Fillbrunn, M.; Simpson, R.; Li, W.; Yang, J.; Le Lorier, Y.; et al. Transfusion-related cost offsets and time burden in patients with myelofibrosis on momelotinib vs. danazol from MOMENTUM. Futur. Oncol. 2024, 20, 2259–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Purser, M.; Gong, C.L.; Elsea, D.; Niehoff, N.; Dlotko, E.; Migliaccio-Walle, K.; Samyshkin, Y. Cost effectiveness of momelotinib vs other treatments for myelofibrosis from a US payer perspective. Poster EE300. In Proceedings of the ISPOR 2024, Atlanta, GA, USA, 5–8 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Purser, M.; Liu, T.; Gorsh, B.; Wang, Z.; Le Lorier, Y.; Strakosch, T.; Samyshkin, Y. Estimating the financial impact of introducing momelotinib as a treatment option for adult patients with intermediate- or high-risk myelofibrosis with anemia from a US commercial and Medicare payer perspective. Poster D16. In Proceedings of the AMCP 2024, New Orleans, LA, USA, 15–18 April 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Week 24 Transfusion Status, n (%) a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Transfusion Status | TI/TR | TD | Total | ||

| Overall population | Momelotinib | TI/TR | 130 (80) | 32 (20) | 162 (75) |

| TD | 20 (38) | 33 (62) | 53 (25) | ||

| Total | 150 (70) | 65 (30) | 215 | ||

| Ruxolitinib | TI/TR | 115 (70) | 50 (30) | 165 (76) | |

| TD | 15 (29) | 37 (71) | 52 (24) | ||

| Total | 130 (60) | 87 (40) | 217 | ||

| Moderate-to-severe anemia subpopulation (Hb < 10 g/dL) | Momelotinib | TI/TR | 25 (68) | 12 (32) | 37 (43) |

| TD | 20 (41) | 29 (59) | 49 (57) | ||

| Total | 45 (52) | 41 (48) | 86 | ||

| Ruxolitinib | TI/TR | 24 (47) | 27 (53) | 51 (54) | |

| TD | 12 (28) | 31 (72) | 43 (46) | ||

| Total | 36 (38) | 58 (62) | 94 | ||

| Moderate anemia subpopulation (Hb ≥ 8 to <10 g/dL) | Momelotinib | TI/TR | 25 (68) | 12 (32) | 37 (64) |

| TD | 9 (43) | 12 (57) | 21 (36) | ||

| Total | 34 (59) | 24 (41) | 58 | ||

| Ruxolitinib | TI/TR | 24 (47) | 27 (53) | 51 (70) | |

| TD | 7 (33) | 15 (68) | 22 (30) | ||

| Total | 31 (42) | 42 (58) | 73 | ||

| Patients aged ≥65 years | Momelotinib | TI/TR | 64 (75) | 21 (25) | 85 (68) |

| TD | 14 (35) | 26 (65) | 40 (32) | ||

| Total | 78 (62) | 47 (38) | 125 | ||

| Ruxolitinib | TI/TR | 58 (64) | 33 (36) | 91 (75) | |

| TD | 8 (26) | 23 (74) | 31 (25) | ||

| Total | 66 (54) | 56 (46) | 122 | ||

| Week 24 Transfusion Status, n (%) a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Transfusion Status | TI/TR | TD | Total | ||

| Overall population | Momelotinib | TI/TR | 27 (59) | 19 (41) | 46 (44) |

| TD | 25 (43) | 33 (57) | 58 (56) | ||

| Total | 52 (50) | 52 (50) | 104 | ||

| BAT | TI/TR | 13 (52) | 12 (48) | 25 (48) | |

| TD | 6 (22) | 21 (78) | 27 (52) | ||

| Total | 19 (37) | 33 (63) | 52 | ||

| Moderate-to-severe anemia subpopulation (Hb < 10 g/dL) | Momelotinib | TI/TR | 5 (36) | 9 (64) | 14 (21) |

| TD | 22 (42) | 30 (58) | 52 (79) | ||

| Total | 27 (41) | 39 (59) | 66 | ||

| BAT | TI/TR | 5 (36) | 9 (64) | 14 (36) | |

| TD | 6 (24) | 19 (76) | 25 (64) | ||

| Total | 11 (28) | 28 (72) | 39 | ||

| Patients aged ≥65 years | Momelotinib | TI/TR | 12 (55) | 10 (45) | 22 (35) |

| TD | 19 (46) | 22 (54) | 41 (65) | ||

| Total | 31 (49) | 32 (51) | 63 | ||

| BAT | TI/TR | 9 (56) | 7 (44) | 16 (42) | |

| TD | 4 (18) | 18 (82) | 22 (58) | ||

| Total | 13 (34) | 25 (66) | 38 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Masarova, L.; Liu, T.; Fillbrunn, M.; Li, W.; Sajeev, G.; Rao, S.; Gorsh, B.; Signorovitch, J. Transfusion-Related Cost and Time Burden Offsets in Patients with Myelofibrosis Treated with Momelotinib in the SIMPLIFY-1 and SIMPLIFY-2 Trials. Cancers 2024, 16, 4067. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16234067

Masarova L, Liu T, Fillbrunn M, Li W, Sajeev G, Rao S, Gorsh B, Signorovitch J. Transfusion-Related Cost and Time Burden Offsets in Patients with Myelofibrosis Treated with Momelotinib in the SIMPLIFY-1 and SIMPLIFY-2 Trials. Cancers. 2024; 16(23):4067. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16234067

Chicago/Turabian StyleMasarova, Lucia, Tom Liu, Mirko Fillbrunn, Weilong Li, Gautam Sajeev, Sumati Rao, Boris Gorsh, and James Signorovitch. 2024. "Transfusion-Related Cost and Time Burden Offsets in Patients with Myelofibrosis Treated with Momelotinib in the SIMPLIFY-1 and SIMPLIFY-2 Trials" Cancers 16, no. 23: 4067. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16234067

APA StyleMasarova, L., Liu, T., Fillbrunn, M., Li, W., Sajeev, G., Rao, S., Gorsh, B., & Signorovitch, J. (2024). Transfusion-Related Cost and Time Burden Offsets in Patients with Myelofibrosis Treated with Momelotinib in the SIMPLIFY-1 and SIMPLIFY-2 Trials. Cancers, 16(23), 4067. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16234067