Concomitant Cervical and Anal Screening for Human Papilloma Virus (HPV): Worth the Effort or a Waste of Time? †

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Settings, Participants, and Sampling

2.2. Statistical Analysis

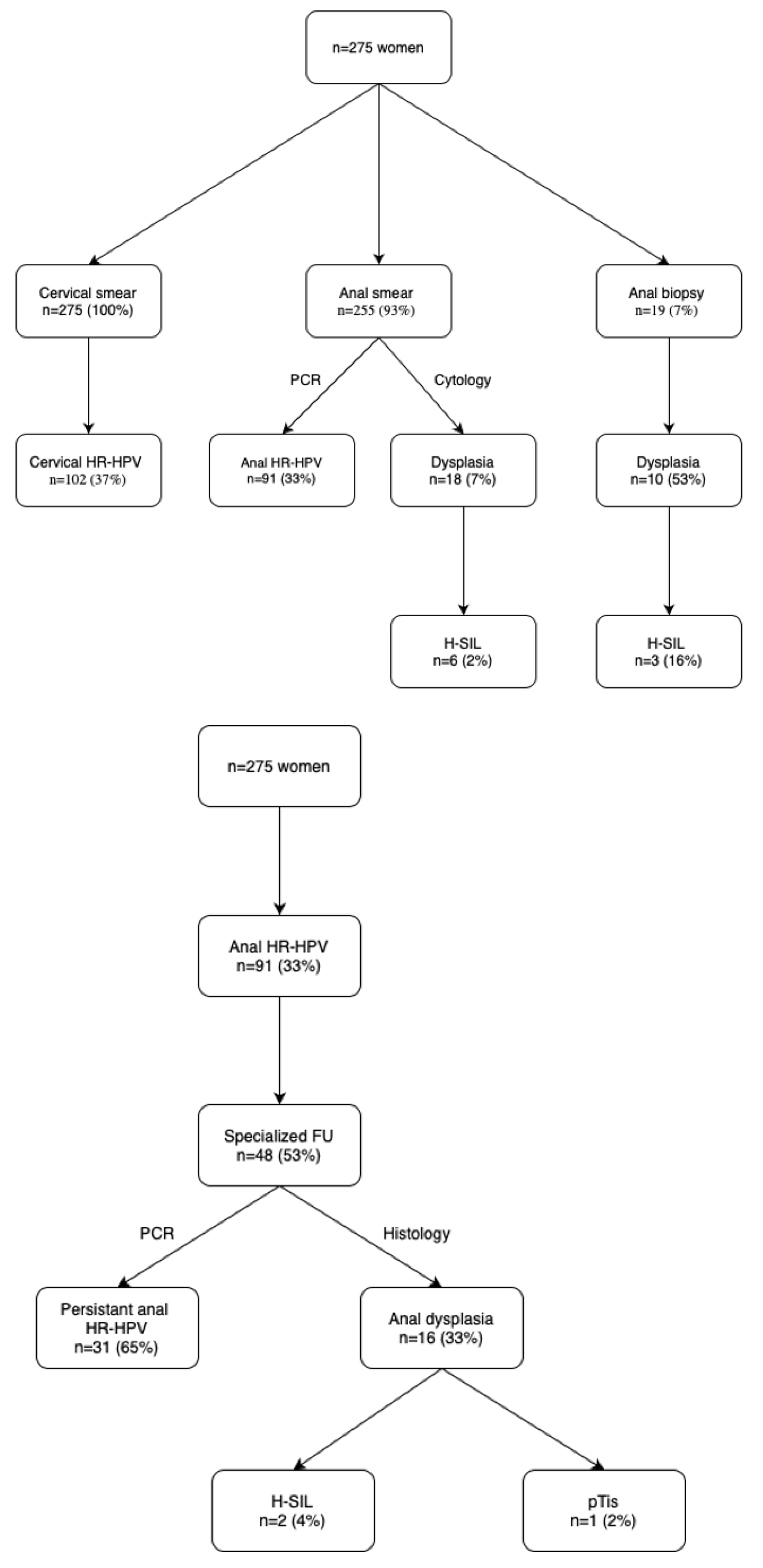

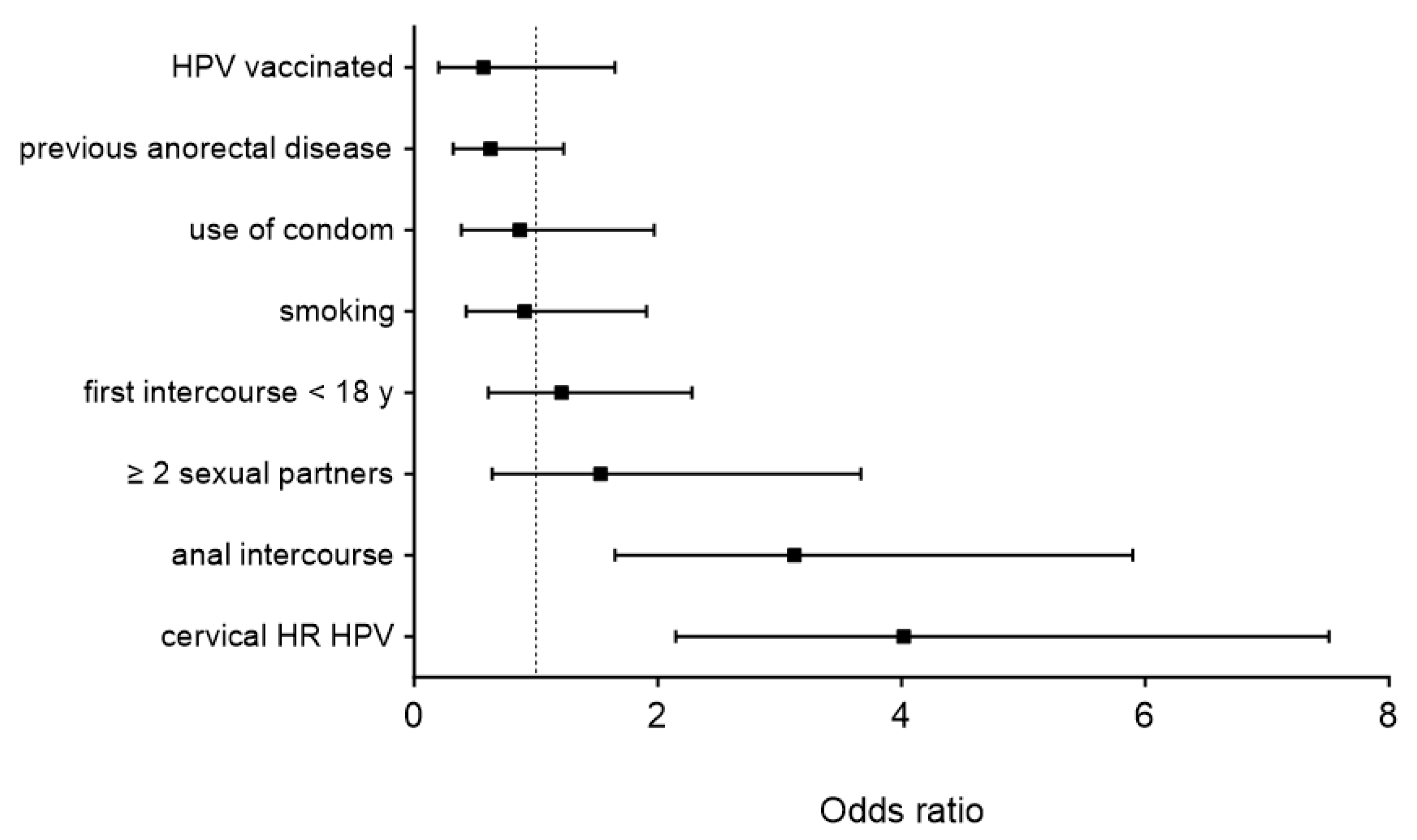

3. Results

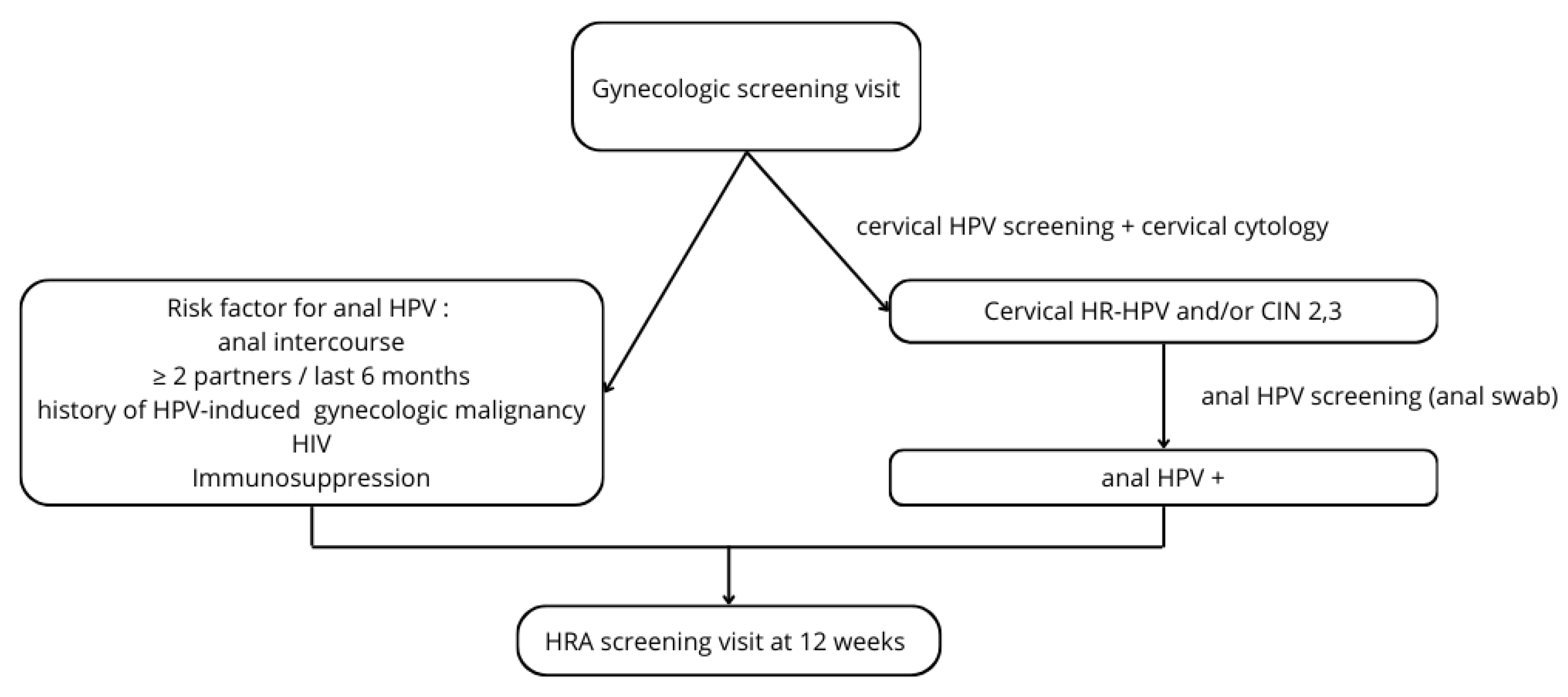

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jensen, J.E.; Becker, G.L.; Jackson, J.B.; Rysavy, M.B. Human Papillomavirus and Associated Cancers: A Review. Viruses 2024, 16, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, J.R.; Siekas, L.L.; Kaz, A.M. Anal intraepithelial neoplasia: A review of diagnosis and management. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2017, 9, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo, I.G.; Felez-Sanchez, M. Papillomaviruses: Viral evolution, cancer and evolutionary medicine. Evol. Med. Public Health 2015, 2015, 32–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, S.V. The human papillomavirus replication cycle, and its links to cancer progression: A comprehensive review. Clin. Sci. 2017, 131, 2201–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aden, D.; Zaheer, S.; Khan, S.; Jairajpuri, Z.S.; Jetley, S. Navigating the landscape of HPV-associated cancers: From epidemiology to prevention. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2024, 263, 155574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manini, I.; Montomoli, E. Epidemiology and prevention of Human Papillomavirus. Ann. Ig. 2018, 30 (Suppl. 1), 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandberg, D.P.; Bhargava, R.; Badin, S.; Cullen, K.J. The role of human papillomavirus in nongenital cancers. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2013, 63, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leber, K.; van Beurden, M.; Zijlmans, H.J.; Dewit, L.; Richel, O.; Vrouenraets, S.M.E. Screening for intra-anal squamous intra-epithelial lesions in women with a history of human papillomavirus-related vulvar or perianal disease: Results of a screening protocol. Colorectal Dis. 2020, 22, 1991–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Bunge, E.; Bakker, M.; Castellsague, X. The incidence, clearance and persistence of non-cervical human papillomavirus infections: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caicedo-Martinez, M.; Fernandez-Deaza, G.; Ordonez-Reyes, C.; Olejua, P.; Nuche-Berenguer, B.; Mello, M.B.; Murillo, R. High-risk human papillomavirus infection among women living with HIV in Latin America and the Caribbean: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. STD AIDS 2021, 32, 1278–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batman, S.; Messick, C.A.; Milbourne, A.; Guo, M.; Munsell, M.F.; Fokom-Domgue, J.; Salcedo, M.; Deshmukh, A.; Dahlstrom, K.R.; Ogburn, M.; et al. A Cross-Sectional Study of the Prevalence of Anal Dysplasia among Women with High-Grade Cervical, Vaginal, and Vulvar Dysplasia or Cancer: The PANDA Study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2022, 31, 2185–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver-Perez, M.L.R.; Bravo Violeta, V.; Legorburu Alonso, B.; Betancor Perez, D.; Bebia Conesa, V.; Jimenez Lopez, J.S. Incidence of Anal Dysplasia in a Population of High-Risk Women: Observations at a Cervical Pathology Unit. J. Low. Genit. Tract. Dis. 2017, 21, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islami, F.; Ferlay, J.; Lortet-Tieulent, J.; Bray, F.; Jemal, A. International trends in anal cancer incidence rates. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 924–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Jiang, C.; Bandi, P.; Minihan, A.; Fidler-Benaoudia, M.; Islami, F.; Siegel, R.L.; Jemal, A. Differences in cancer rates among adults born between 1920 and 1990 in the USA: An analysis of population-based cancer registry data. Lancet Public Health 2024, 9, e583–e593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacot-Guillarmod, M.; Balaya, V.; Mathis, J.; Hubner, M.; Grass, F.; Cavassini, M.; Sempoux, C.; Mathevet, P.; Pache, B. Women with Cervical High-Risk Human Papillomavirus: Be Aware of Your Anus! The ANGY Cross-Sectional Clinical Study. Cancers 2022, 14, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pache, B.; Balaya, V.; Mathis, J.; Hubner, M.; Sahli, R.; Cavassini, M.; Sempoux, C.; Mathevet, P.; Jacot-Guillarmod, M. Prevalence of anal dysplasia and HPV genotypes in gynecology patients: The ANGY cross-sectional prospective clinical study protocol. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espirito Santo, I.; Duvoisin Cordoba, C.; Hubner, M.; Faes, S.; Hahnloser, D.; Grass, F. [Anal cancer screening. A decade’s experience of a consultation in a tertiary centre]. Rev. Med. Suisse 2023, 19, 1186–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierangeli, A.; Scagnolari, C.; Selvaggi, C.; Cannella, F.; Riva, E.; Impagnatiello, A.; Bernardi, G.; Ciardi, A.; Moschella, C.M.; Antonelli, G.; et al. High detection rate of human papillomavirus in anal brushings from women attending a proctology clinic. J. Infect. 2012, 65, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehnal, B.; Dusek, L.; Cibula, D.; Zima, T.; Halaska, M.; Driak, D.; Slama, J. The relationship between the cervical and anal HPV infection in women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J. Clin. Virol. 2014, 59, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stier, E.A.; Lensing, S.Y.; Darragh, T.M.; Deshmukh, A.A.; Einstein, M.H.; Palefsky, J.M.; Jay, N.; Berry-Lawhorn, J.M.; Wilkin, T.; Wiley, D.J.; et al. Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Anal High-grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions in Women Living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 70, 1701–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindquist, S.; Frederiksen, K.; Petersen, L.K.; Kjaer, S.K. The risk of vaginal, vulvar and anal precancer and cancer according to high-risk HPV status in cervical cytology samples. Int. J. Cancer 2024, 155, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Z.; Yixin, S.; Jianyu, C.; Xiang, T.; Long, S.; Qing, C. Anal intraepithelial neoplasia screening in women from the largest center for lower genital tract disease in China. J. Med. Virol. 2024, 96, e29747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesic, V.; Carcopino, X.; Preti, M.; Vieira-Baptista, P.; Bevilacqua, F.; Bornstein, J.; Chargari, C.; Cruickshank, M.; Erzeneoglu, E.; Gallio, N.; et al. The European Society of Gynaecological Oncology (ESGO), the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD), the European College for the Study of Vulval Disease (ECSVD), and the European Federation for Colposcopy (EFC) Consensus Statement on the Management of Vaginal Intraepithelial Neoplasia. J. Low. Genit. Tract. Dis. 2023, 27, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balgovind, P.; Aung, E.; Shilling, H.; Murray, G.L.; Molano, M.; Garland, S.M.; Fairley, C.K.; Chen, M.Y.; Hocking, J.S.; Ooi, C.; et al. Human papillomavirus prevalence among Australian men aged 18-35 years in 2015-2018 according to vaccination status and sexual preference. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, jiae412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, K.; Shaw, J.; Suryadevara, M.; Stephens, A. Optimizing Protection Against HPV-Related Cancer: Unveiling the Benefits and Overcoming Challenges of HPV Vaccination. Pediatr. Ann. 2024, 53, e372–e377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, S.F.; Andersen, B.; Petersen, L.K.; Rebolj, M.; Njor, S.H. Adherence to follow-up after the exit cervical cancer screening test at age 60-64: A nationwide register-based study. Cancer Med. 2022, 11, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stier, E.A.; Clarke, M.A.; Deshmukh, A.A.; Wentzensen, N.; Liu, Y.; Poynten, I.M.; Cavallari, E.N.; Fink, V.; Barroso, L.F.; Clifford, G.M.; et al. International Anal Neoplasia Society’s consensus guidelines for anal cancer screening. Int. J. Cancer 2024, 154, 1694–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.A.; Deshmukh, A.A.; Suk, R.; Roberts, J.; Gilson, R.; Jay, N.; Stier, E.A.; Wentzensen, N. A systematic review and meta-analysis of cytology and HPV-related biomarkers for anal cancer screening among different risk groups. Int. J. Cancer 2022, 151, 1889–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capell-Morell, M.; Bradbury, M.; Dinares, M.C.; Hernandez, J.; Cubo-Abert, M.; Centeno-Mediavilla, C.; Gil-Moreno, A. Anal high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer in women living with HIV and HIV-negative women with other risk factors. AIDS 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamolratanakul, S.; Pitisuttithum, P. Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Efficacy and Effectiveness against Cancer. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Tenorio, C.; Moya, R.; Omar, M.; Munoz, L.; SamPedro, A.; Lopez-Hidalgo, J.; Garcia-Vallecillos, C.; Gomez-Ronquillo, P. Safety and Immunogenicity of the Nonavalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine in Women Living with HIV. Vaccines 2024, 12, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | All Patients (n = 275) | Anal HR-HPV (n = 91) | Controls (n = 184) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 42 ± 12 | 41 ± 12 | 43 ± 12 | 0.141 |

| Smoking (%) | 62/263 (24) | 24/89 (27) | 38/174 (22) | 0.361 |

| Cervical HR-HPV (%) | 102 (37) | 54 (59) | 48 (32) | <0.001 |

| ≥2 sexual partners (%) | 208/265 (78) | 79/88 (90) | 129/177 (73) | 0.001 |

| Age of first intercourse < 18 y (%) | 134/262 (51) | 43/88 (49) | 91/174 (52) | 0.604 |

| Use of condom (%) | 49/266 (18) | 16 (18) | 33/175 (19) | 0.869 |

| Anal intercourse (%) | 97/270 (36) | 48 (53) | 49/179 (27) | <0.001 |

| Previous anorectal disease (%) | 84/267 (31) | 26/89 (29) | 58/178 (33) | 0.675 |

| HPV vaccinated (%) | 25/261 (10) | 9/88 (10) | 16/173 (9) | 0.826 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chilou, C.; Espirito Santo, I.; Faes, S.; St-Amour, P.; Jacot-Guillarmod, M.; Pache, B.; Hübner, M.; Hahnloser, D.; Grass, F. Concomitant Cervical and Anal Screening for Human Papilloma Virus (HPV): Worth the Effort or a Waste of Time? Cancers 2024, 16, 3534. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16203534

Chilou C, Espirito Santo I, Faes S, St-Amour P, Jacot-Guillarmod M, Pache B, Hübner M, Hahnloser D, Grass F. Concomitant Cervical and Anal Screening for Human Papilloma Virus (HPV): Worth the Effort or a Waste of Time? Cancers. 2024; 16(20):3534. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16203534

Chicago/Turabian StyleChilou, Camille, Iolanda Espirito Santo, Seraina Faes, Pénélope St-Amour, Martine Jacot-Guillarmod, Basile Pache, Martin Hübner, Dieter Hahnloser, and Fabian Grass. 2024. "Concomitant Cervical and Anal Screening for Human Papilloma Virus (HPV): Worth the Effort or a Waste of Time?" Cancers 16, no. 20: 3534. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16203534

APA StyleChilou, C., Espirito Santo, I., Faes, S., St-Amour, P., Jacot-Guillarmod, M., Pache, B., Hübner, M., Hahnloser, D., & Grass, F. (2024). Concomitant Cervical and Anal Screening for Human Papilloma Virus (HPV): Worth the Effort or a Waste of Time? Cancers, 16(20), 3534. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16203534