Caring for Pregnant Patients with Cancer: A Framework for Ethical and Patient-Centred Care

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Ethical Models Applicable to Cancer Care during Pregnancy

| Ethical Models Used to Develop the Guidance | Model Description and Specification | Key References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle-based approaches | Four principles for biomedical ethics (Georgetown principles) by Beauchamp and Childress | Respect to patient’s autonomy, including relational aspects Nonmaleficence: avoiding harm before doing good Beneficence: maximising the benefit for the pregnant patient and developing foetus Justice: considering a big picture and a broader context | [42] |

| European principles of bioethics and biolaw presented by Rendtorff | Autonomy: individual freedom to make choices Dignity: moral responsibility to human life Integrity: right to bodily integrity, right to refuse treatment Vulnerability (respect to vulnerability): recognising human vulnerabilities, protecting vulnerable groups | [43,44] | |

| Relational, patient-focused approaches | Relational ethics | Trusted relationship building with the patient Patient-centric approach to patient care Interdependency and freedom Emotions and reason | [47,48] |

| Care ethics (ethics of care) | Compassion to patient’s suffering Presence in patient’s unique situation, active listening Empathy to patient’s feelings and circumstances Recognition of a patient as fellow human being | [45,46] | |

| Medical maternalism | Shared decision making Accessible evidence-based information Conversation and understanding of patient’s circumstances and best interest Patient guidance through clinical advice and reason | [49,50] |

2.1. Principle-Based Approaches

2.2. Relational, Patient-Focused Approaches

3. Discussion Themes for Ethical, Patient-Centred Cancer Care during Pregnancy

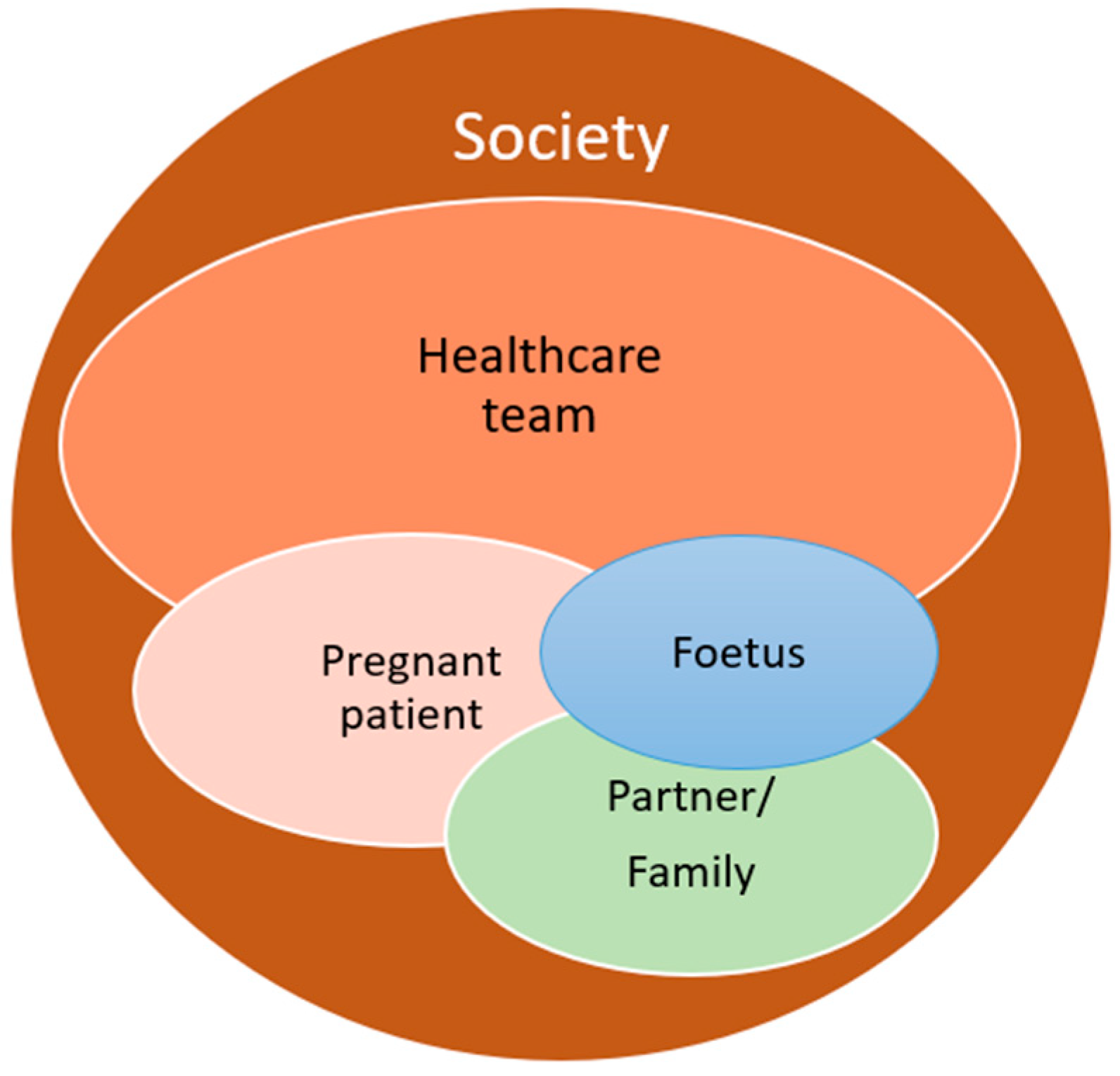

3.1. Recognising Relational Context of Individual Patient’s Autonomy

3.2. Balancing Maternal and Foetal Beneficence

3.3. Balancing Maternalistic and Relational Approach to Evidence-Based, Personalised Patient Care

3.4. Considering Protection of the Vulnerable

3.5. Ensuring Reasonable and Just Resource Allocation

4. Ethics Checklist for Healthcare Professionals Attending to Pregnant Cancer Patients

Ethics Checklist to Support Decision-Making Process in Treatment and Care of Pregnant Cancer Patients

- Perform an accurate clinical assessment to be able to discuss the disease prognosis, treatment intent (curative vs. palliative) and its impact on pregnancy.

- Identify the patient’s social and relational circumstances (e.g., spouse/partner/significant other; children; other relevant relationships; literacy and information comprehension level; occupation/employment situation; housing arrangements; socio-economic status; religion/spiritual/philosophical beliefs and needs; family/relational dynamics; gender identification; social roles important to the patient; etc.)

- Recognise the potential vulnerability of the pregnant cancer patient, take time to listen to patient’s concerns and fears, allow time to ask questions. Be informed about support services available for these patients.

- Recognise the developing foetus as a vulnerable entity and in need of protection by its parents as much as healthcare professionals. Take into consideration the gestational age of the foetus and the local legal requirements around pregnancy termination for medical reasons.

- Confirm and document patients’ decision-making capacity:

- ○

- If the patient is capable of consenting to medical treatment and interventions:

- ○

- Discuss with the patient their preferences regarding the medical decision-making process and communication with clinical team.

- ○

- Discuss with the patient their preferences, expectations and perceptions about their desired cancer treatment and pregnancy outcome in their individual situation and care priorities, existing and desired advance care directives.

- ○

- Support the patient with drafting, completing or updating the advance care directives, clearly document the patient’s intent for which circumstances they are applicable.

- ○

- Identify other stakeholders involved in the clinical decision-making process (e.g., partner, parents, etc.) whose involvement is important to the patient.

- ○

- Document all relevant information in the patient’s notes/electronic medical records.

- ○

- If the patient is not capable of consenting to medical treatment and interventions (unconscious, lacks capacity to make decisions):

- ○

- Identify the surrogate decision maker, ask about their own wellbeing and support needs, share information about available support.

- ○

- Discuss the perceived patient and their caregiver(s)’ preferences with the surrogate decision maker, establish the expectations and perceptions about the desirable disease treatment and pregnancy outcome and care priorities, known/existing advance care directives, including the views and wishes the patient is known to have had expressed in the past.

- ○

- Identify other stakeholders, who might need to be involved in the medical decision-making process (e.g., partner, parents, etc.) in order to establish the best interest of the patient and developing foetus.

- ○

- If the patient is conscious, involve them in the conversation about their treatment and care options, where possible and practical.

- ○

- Document all relevant information in the patient’s notes/electronic medical records.

- Upon confirming the decision-making capacity, share evidence-based information regarding treatment options and related clinical outcomes, expected short- and long-term toxicities for the patient and the developing foetus.

- Inform the patient/surrogate decision maker about ongoing cancer during pregnancy research and available options for participation in clinical trials.

- Involve a multidisciplinary team that includes different medical specialties with expertise in care of pregnant patients with cancer and other healthcare professionals, such as nurses, psychologists, social workers, hospital ethics committee/ethics advisory board, ethical and spiritual care providers, etc.

- Obtain a written consent to treatment and/or care plan (if required by local regulations), allowing adequate time for decision making, following the discussion on available cancer and pregnancy management options.

- Where written consent to treatment/care plan is not a routine or mandatory requirement, allow adequate time for decision making, following the discussion on available cancer and pregnancy management options and document it in the patient’s notes/electronic medical records.

- Clearly document patient’s/surrogate decision maker’s decisions, concerns and explanation given on treatment and care in patient’s notes/electronic medical records.

- Periodically review changes in patient’s treatment and care plan, updating consent documentation as per local legal requirements and professional guidance.

- Seek consultation with other hospital/care facility teams (hospital ethics committee/ethics advisory board, social services, patient financial support, patient counselling, etc.) if available healthcare resources are not adequate for handling a particular patient’s case, if patient’s or surrogate decision maker’s treatment/care preferences are futile and might result in significant financial burden to the healthcare system or themselves.

- Ensure that the patient/surrogate decision maker are aware of an option to request a second opinion from another doctor/multidisciplinary team without retaliation from the treating doctor/team or administration.

- Should patient/surrogate decision makers refuse treatment or suggested care pathway, seek to understand the reasons behind it, be ready to answer questions and give time to consider the options without retaliation from the treating doctor/team or administration.

- Identify existing and potential concerns within the clinical team based on legal considerations, political leaning, religious beliefs and personal preferences; seek reconciliation of such concerns in a structured manner (e.g., moral case deliberation, clinical ethics consultation, ethical counselling, etc.)

- Acknowledge the rights and their legal/professional limits for clinical and supporting team members to exercise conscientious objections (e.g., administering treatment to a pregnant patient that can potentially harm the foetus, carrying out abortion/pregnancy termination procedures, proving post-abortion care to cancer patients, etc.), constructively engage concerned team members, seek council with the legal team, ethics consultation service, senior management, etc., to ensure that patient safety, continuity of treatment and care are not compromised due to moral objections leading to staff shortage.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cubillo, A.; Morales, S.; Goñi, E.; Matute, F.; Muñoz, J.L.; Pérez-Díaz, D.; de Santiago, J.; Rodríguez-Lescure, Á. Multidisciplinary consensus on cancer management during pregnancy. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2021, 23, 1054–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaemi, S.; Keshavarz, Z.; Tahmasebi, S.; Akrami, M.; Heydari, S. Conflicts women with breast cancer face with: A qualitative study. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkeviciute, A.; Notarangelo, M.; Buonomo, B.; Bellettini, G.; Peccatori, F.A. Breastfeeding After Breast Cancer: Feasibility, Safety, and Ethical Perspectives. J. Hum. Lact. 2020, 36, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambertini, M.; Kroman, N.; Ameye, L.; Cordoba, O.; Pinto, A.; Benedetti, G.; Jensen, M.-B.; Gelber, S.; Del Grande, M.; Ignatiadis, M.; et al. Long-term Safety of Pregnancy Following Breast Cancer According to Estrogen Receptor Status. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 426–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Q.; Deng, D.; Xie, Q.; Gong, X.; Meng, X.; Xia, Y.; Ai, J.; Li, K. Clinical characteristics, pregnancy outcomes and ovarian function of pregnancy-associated breast cancer patients: A retrospective age-matched study. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catania, C.; Del Signore, E.; Spitaleri, G. The Desire for Life and Motherhood Despite Metastatic Lung Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amant, F.; Berveiller, P.; Boere, I.A.; Cardonick, E.; Fruscio, R.; Fumagalli, M.; Halaska, M.J.; Hasenburg, A.; Johansson, A.L.V.; Lambertini, M.; et al. Gynecologic cancers in pregnancy: Guidelines based on a third international consensus meeting. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1601–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, T.; Lankester, K.; Kelly, T.; Watkins, R.; Kaushik, S. Cervical cancer in pregnancy: Diagnosis, staging and treatment. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 24, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggen, C.; Wolters, V.; Van Calsteren, K.; Cardonick, E.; Laenen, A.; Heimovaara, J.H.; Mhallem Gziri, M.; Fruscio, R.; Duvekot, J.J.; Painter, R.C.; et al. Impact of chemotherapy during pregnancy on fetal growth. J. Matern. Neonatal Med. 2022, 35, 10314–10323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalet, M.; Dejean, C.; Schick, U.; Durdux, C.; Fourquet, A.; Kirova, Y. Radiotherapy and pregnancy. Cancer/Radiotherapie 2022, 26, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Moor, R.J.; Walpole, E.T.; Atkinson, V.G. Pregnancy with successful foetal and maternal outcome in a melanoma patient treated with nivolumab in the first trimester: Case report and review of the literature. Melanoma Res. 2019, 29, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baarslag, M.A.; Heimovaara, J.H.; Borgers, J.S.W.; van Aerde, K.J.; Koenen, H.J.P.M.; Smeets, R.L.; Buitelaar, P.L.M.; Pluim, D.; Vos, S.; Henriet, S.S.V.; et al. Severe Immune-Related Enteritis after In Utero Exposure to Pembrolizumab. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1790–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittra, A.; Naqash, A.R.; Murray, J.H.; Finnigan, S.; Kwak-Kim, J.; Ivy, S.P.; Chen, A.P.; Sharon, E. Outcomes of Pregnancy During Immunotherapy Treatment for Cancer: Analysis of Clinical Trials Sponsored by the National Cancer Institute. Oncologist 2021, 26, e1883–e1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi, I.; Porto, L.; Elser, C.; Singh, J.; Saibil, S.; Maxwell, C. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Exposure in Pregnancy: A Scoping Review. J. Immunother. 2022, 45, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evens, A.M.; Sharon, E.; Brandt, J.S.; Peer, C.J.; Yin, T.; Mozarsky, B.; Figg, W.D. Checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy during pregnancy for relapsed—Refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Am. J. Hematol. 2022, 97, 833–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.Y.; Hu, Q.L.; Zhou, Q. Use of trastuzumab in treating breast cancer during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Women’s Health 2021, 21, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrikopoulou, A.; Apostolidou, K.; Chatzinikolaou, S.; Bletsa, G.; Zografos, E.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Zagouri, F. Trastuzumab administration during pregnancy: Un update. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gougis, P.; Grandal, B.; Jochum, F.; Bihan, K.; Coussy, F.; Barraud, S.; Asselain, B.; Dumas, E.; Sebbag, C.; Hotton, J.; et al. Treatments During Pregnancy Targeting ERBB2 and Outcomes of Pregnant Individuals and Newborns. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2339934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggio, F.; Tagliamento, M.; Pirrone, C.; Soldato, D.; Conte, B.; Molinelli, C.; Cosso, M.; Fregatti, P.; Del Mastro, L.; Lambertini, M. Update on the management of breast cancer during pregnancy. Cancers 2020, 12, 3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margioula-Siarkou, G.; Margioula-Siarkou, C.; Petousis, S.; Vavoulidis, E.; Margaritis, K.; Almperis, A.; Haitoglou, C.; Mavromatidis, G.; Dinas, K. Breast Carcinogenesis during Pregnancy: Molecular Mechanisms, Maternal and Fetal Adverse Outcomes. Biology 2023, 12, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibelli, B.; Zamperini, P.; Proh, M.; Giugliano, G. Management and follow-up of thyroid cancer in pregnant women. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2011, 31, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khaled, H.; Al Lahloubi, N.; Rashad, N. A review on thyroid cancer during pregnancy: Multitasking is required. J. Adv. Res. 2016, 7, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beharee, N.; Shi, Z.; Wu, D.; Wang, J. Diagnosis and treatment of cervical cancer in pregnant women. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 5425–5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Xie, C.; Qi, X.; Hu, Z.; He, Y. The effect of preserving pregnancy in cervical cancer diagnosed during pregnancy: A retrospective study. BMC Women’s Health 2022, 22, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinnix, C.C.; Osborne, E.M.; Chihara, D.; Lai, P.; Zhou, S.; Ramirez, M.M.; Oki, Y.; Hagemeister, F.B.; Rodriguez, A.M.; Samaniego, F.; et al. Maternal and Fetal Outcomes After Therapy for Hodgkin or Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Diagnosed During Pregnancy. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Maggen, C.; Dierickx, D.; Lugtenburg, P.; Laenen, A.; Cardonick, E.; Smakov, R.G.; Bellido, M.; Cabrera-Garcia, A.; Gziri, M.M.; Halaska, M.J.; et al. Obstetric and maternal outcomes in patients diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma during pregnancy: A multicentre, retrospective, cohort study. Lancet Haematol. 2019, 6, e551–e561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berk-Krauss, J.; Liebman, T.N.; Stein, J.A. Pregnancy and Melanoma: Recommendations for Clinical Scenarios. Int. J. Women’s Dermatol. 2018, 4, 113–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, T.J.; George, C.; Harwood, C.; Nathan, P. Melanoma in pregnancy: Diagnosis and management in early-stage and advanced disease. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 166, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiro, R.; Murakami, K.; Miyauchi, M.; Sanada, Y.; Matsumura, N. Management strategies for brain tumors diagnosed during in pregnancy: A case report and literature review. Medicina 2021, 57, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.J.; Waldrop, A.R.; Suharwardy, S.; Druzin, M.L.; Iv, M.; Ansari, J.R.; Stone, S.A.; Jaffe, R.A.; Jin, M.C.; Li, G.; et al. Management of brain tumors presenting in pregnancy: A case series and systematic review. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2021, 3, 100256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussios, S.; Han, S.N.; Fruscio, R.; Halaska, M.J.; Ottevanger, P.B.; Peccatori, F.A.; Koubková, L.; Pavlidis, N.; Amant, F. Lung cancer in pregnancy: Report of nine cases from an international collaborative study. Lung Cancer 2013, 82, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, A.; dos Santos, J.; Silva, A.; Magalhães, H.; Estevinho, F.; Sottomayor, C. Treatment of lung cancer during pregnancy. Pulmonology 2020, 26, 314–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linkeviciute, A.; Buonomo, B.; Fazio, N.; Spada, F.; Peccatori, F.A. Discussing motherhood when the oncological prognosis is dire: Ethical considerations for physicians. ESMO Open 2020, 5, e000956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkeviciute, A. Cancer During Pregnancy: A Framework for Ethical Care. 2017. Available online: https://air.unimi.it/handle/2434/449004#.YNNNbFT0ldg (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Memaryan, N.; Ghaempanah, Z.; Saeedi, M.M.; Aryankhesal, A.; Ansarinejad, N.; Seddigh, R. Content of spiritual counselling for cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy in Iran: A qualitative content analysis. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2017, 18, 1791–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.I.; Sabir, Q.u.A.; Shafqat, A.; Aslam, M. Exploring the psychological and religious perspectives of cancer patients and their future financial planning: A Q-methodological approach. BMC Palliat. Care 2022, 21, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boniolo, G.; Sanchini, V. Counselling and Medical Decision-Making in the Era of Personalised Medicine; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-27690-8 (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Silverstein, J.; Post, A.L.; Chien, A.J.; Olin, R.; Tsai, K.K.; Ngo, Z.; Van Loon, K. Multidisciplinary Management of Cancer During Pregnancy. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2020, 16, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linkeviciute, A.; Canario, R.; Peccatori, F.A.; Dierickx, K. Guidelines for Cancer Treatment during Pregnancy: Ethics-Related Content Evolution and Implications for Clinicians. Cancers 2022, 14, 4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorouri, K.; Loren, A.W.; Amant, F.; Partridge, A.H. Patient-Centered Care in the Management of Cancer During Pregnancy. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2023, 43, e100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpuim Costa, D.; Nobre, J.G.; de Almeida, S.B.; Ferreira, M.H.; Gonçalves, I.; Braga, S.; Pais, D. Cancer During Pregnancy: How to Handle the Bioethical Dilemmas?—A Scoping Review With Paradigmatic Cases-Based Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 598508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, T.L.; Childress, J.F. Principles of Biomedical Ethics, 8th ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rendtorff, J.D. The Second International Conference about Bioethics and Biolaw: European principles in bioethics and biolaw. Med. Health Care. Philos. 1998, 1, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendtorff, J.D. Basic ethical principles in European bioethics and biolaw: Autonomy, dignity, integrity and vulnerability--towards a foundation of bioethics and biolaw. Med. Health Care. Philos. 2002, 5, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Heijst, A.; Leget, C. Ethics of care, compassion and recognition. In Care, Compassion and Recognition: An Ethical Discussion; Leget, C., Gastmans, C., Verkerk, M., Eds.; Peeters: Leuven, Belgium, 2011; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Newnham, E.; Kirkham, M. Beyond autonomy: Care ethics for midwifery and the humanization of birth. Nurs. Ethics 2019, 26, 2147–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, W.J. Relational Ethics. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods; Given, L.M., Ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, J.; Engel, J.; Prentice, D. Relational ethics in everyday practice. Can. Oncol. Nurs. J. 2014, 24, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Specker Sullivan, L. Medical maternalism: Beyond paternalism and antipaternalism. J. Med. Ethics 2016, 42, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Specker Sullivan, L.; Niker, F. Relational Autonomy, Paternalism, and Maternalism. Ethical Theory Moral Pract. 2018, 21, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varkey, B. Principles of Clinical Ethics and Their Application to Practice. Med. Princ. Pract. 2021, 30, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.K.; Tavaglione, N.; Hurst, S. Resolving the Conflict: Clarifying ‘Vulnerability’ in Health Care Ethics. Kennedy Inst. Ethics J. 2014, 24, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Have, H. Respect for Human Vulnerability: The Emergence of a New Principle in Bioethics. J. Bioeth. Inq. 2015, 12, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottow, M.H. The vulnerable and the susceptible. Bioethics 2003, 17, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavaglione, N.; Martin, A.K.; Mezger, N.; Durieux-Paillard, S.; François, A.; Jackson, Y.; Hurst, S. Fleshing Out Vulnerability. Bioethics 2013, 29, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, D. Narrative self-constitution and vulnerability to co-authoring. Theor. Med. Bioeth. 2016, 37, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackenzie, C.; Stoljar, N. Introduction: Autonomy refigured. In Relational Autonomy: Feminist Perspectives on Autonomy, Agency, and the Social Self; Mackenzie, C., Stoljar, N., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- DeGrazia, D. Human Identity and Bioethics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sargent, C.; Smith-Morris, C. Questioning Our Principles: Anthropological Contributions to Ethical Dilemmas in Clinical Practice. Camb. Q. Healthc. Ethics 2006, 15, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aburas, R.; Devereaux, M. Maternal Fetal Conflict from Legal Point of View Comparing Health Law in the United States and Islamic Law. Open J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 7, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westra, A.E.; Willems, D.L.; Smit, B.J. Communicating with Muslim parents: “the four principles” are not as culturally neutral as suggested. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2009, 168, 1383–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iltis, A.S. Bioethics as methodological case resolution: Specification, specified principlism and casuistry. J. Med. Philos. 2000, 25, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kaltoft, M.K.; Nielsen, J.B.; Salkeld, G.; Dowie, J. Towards integrating the principlist and casuist approaches to ethical decisions via multi-criterial support. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2016, 225, 540–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Heijst, A. Professional Loving Care: An Ethical View of the Healthcare Sector; Peeters: Leuven, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chervenak, F.A.; McCullough, L.B.; Knapp, R.C.; Caputo, T.A.; Barber, H.R.K. A clinically comprehensive ethical framework for offering and recommending cancer treatment before and during pregnancy. Cancer 2004, 100, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, L.R.; Stanhope, K.K.; Rochat, R.W.; Bernal, O.A. “The fetus is my patient, too”: Attitudes toward abortion and referral among physician conscientious objectors in Bogotá, Colombia. Int. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2016, 42, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuman, A.G.; Aapro, M.S.; Anderson, B.; Arbour, K.; Barata, P.C.; Bardia, A.; Bruera, E.; Chabner, B.A.; Chen, H.; Choy, E.; et al. Supporting Patients with Cancer after Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. Oncologist 2022, 27, 711–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.X.; Booth, A.; Ourselin, S.; David, A.L.; Ashcroft, R. The legal frameworks that govern fetal surgery in the United Kingdom, European Union, and the United States. Prenat. Diagn. 2018, 38, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odozor, U.S.; Obilor, H.N.; Thompson, O.O.; Odozor, N.S. A Rationalist Critique of Sally Gadow’s Relational Nursing Ethics. UJAH Unizik J. Arts Humanit. 2021, 22, 27–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmuş, D. Care Ethics and Paternalism: A Beauvoirian Approach. Philosophies 2022, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkeviciute, A.; Peccatori, F.A.; Sanchini, V.; Boniolo, G. Oocyte cryopreservation beyond cancer: Tools for ethical reflection. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2015, 32, 1211–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Chiavari, L.; Gandini, S.; Feroce, I.; Guerrieri-Gonzaga, A.; Russell-Edu, W.; Bonanni, B.; Peccatori, F.A. Difficult choices for young patients with cancer: The supportive role of decisional counseling. Support. Care Cancer 2015, 23, 3555–3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, A.K.; Klock, S.C.; Pavone, M.E.; Hirshfeld-Cytron, J.; Smith, K.N.; Kazer, R.R. Psychological Counseling of Female Fertility Preservation Patients. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2015, 33, 333–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Jones, G.L.; Culligan, D.J.; Marsden, P.J.; Russell, N.; Embleton, N.D.; Craddock, C. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukaemia in pregnancy. Br. J. Haematol. 2015, 170, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bluemel, C.; Herrmann, K.; Giammarile, F.; Nieweg, O.E.; Dubreuil, J.; Testori, A.; Audisio, R.A.; Zoras, O.; Lassmann, M.; Chakera, A.H.; et al. EANM practice guidelines for lymphoscintigraphy and sentinel lymph node biopsy in melanoma. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2015, 42, 1750–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibula, D.; Pötter, R.; Planchamp, F.; Avall-Lundqvist, E.; Fischerova, D.; Haie-Meder, C.; Köhler, C.; Landoni, F.; Lax, S.; Lindegaard, J.C.; et al. The European Society of Gynaecological Oncology/European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology/European Society of Pathology Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Cervical Cancer. Virchows Arch. 2018, 472, 919–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, E.K.; Pearce, E.N.; Brent, G.A.; Brown, R.S.; Chen, H.; Dosiou, C.; Grobman, W.A.; Laurberg, P.; Lazarus, J.H.; Mandel, S.J.; et al. 2017 Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Disease during Pregnancy and the Postpartum. Thyroid 2017, 27, 315–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallera, A.; Altman, J.K.; Berman, E.; Abboud, C.N.; Bhatnagar, B.; Curtin, P.; DeAngelo, D.J.; Gotlib, J.; Tanner Hagelstrom, R.; Hobbs, G.; et al. NCCN guidelines® insights: Chronic myeloid leukemia, version 1.2017: Featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. JNCCN J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2016, 14, 1505–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, P.F.; Pappo, A.S.; Beaupin, L.; Borges, V.F.; Borinstein, S.C.; Chugh, R.; Dinner, S.; Folbrecht, J.; Frazier, A.L.; Goldsby, R.; et al. Adolescent and young adult oncology, version 2.2018: Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. JNCCN J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2018, 16, 66–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, N.; Balega, J.; Barwick, T.; Buckley, L.; Burton, K.; Eminowicz, G.; Forrest, J.; Ganesan, R.; Harrand, R.; Holland, C.; et al. British Gynaecological Cancer Society (BGCS) cervical cancer guidelines: Recommendations for practice. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 256, 433–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollard, C.L. What is the Right Thing to Do: Use of a Relational Ethic Framework to Guide Clinical Decision-Making. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2015, 8, 362–368. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen, L.M.; Sunde Mæhre, K. Can a structured model of ethical reflection be used to teach ethics to nursing students? An approach to teaching nursing students a tool for systematic ethical reflection. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feary, V. Virtue-Based Feminist Philosophical Counselling. Pract. Philos. 2003, 6, 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Vanlaere, L.; Gastmans, C. To be is to care: A philosophical-ethical analysis of care with a view from nursing. In Care, Compassion and Recognition: An Ethical Discussion; Leget, C., Gastmans, C., Verkerk, M., Eds.; Peeters: Leuven, Belgium, 2011; pp. 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cornetta, K.; Brown, C.G. Balancing Personalized Medicine and Personalized Care. Acad. Med. 2013, 88, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmaeilzadeh, M.; Dictus, C.; Kayvanpour, E.; Sedaghat-Hamedani, F.; Eichbaum, M.; Hofer, S.; Engelmann, G.; Fonouni, H.; Golriz, M.; Schmidt, J.; et al. One life ends, another begins: Management of a brain-dead pregnant mother—A systematic review. BMC Med. 2010, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, M.K. Vulnerability, therapeutic misconception and informed consent: Is there a need for special treatment of pregnant women in fetus-regarding clinical trials? J. Med. Ethics 2015, 42, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begović, D. Maternal–Fetal Surgery: Does Recognising Fetal Patienthood Pose a Threat to Pregnant Women’s Autonomy? Health Care Anal. 2021, 29, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmberger, E.; Bolund, C.; Lützén, K. Experience of dealing with moral responsibility as a mother with cancer. Nurs. Ethics 2005, 12, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearnley, R.; Boland, J.W. Communication and support from health-care professionals to families, with dependent children, following the diagnosis of parental life-limiting illness: A systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2017, 31, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fearnley, R.; Boland, J.W. Parental life-limiting illness: What do we tell the children? Healthcare 2019, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, E.M.; Stephenson, E.M.; Moore, C.W.; Deal, A.M.; Muriel, A.C. Parental psychological distress and cancer stage: A comparison of adults with metastatic and non-metastatic cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 2443–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenyon, S.; Dixon-Woods, M.; Jackson, C.J.; Windridge, K.; Pitchforth, E. Participating in a trial in a critical situation: A qualitative study in pregnancy. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2006, 15, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smyth, R.M.D.; Jacoby, A.; Elbourne, D. Deciding to join a perinatal randomised controlled trial: Experiences and views of pregnant women enroled in the Magpie Trial. Midwifery 2012, 28, e538–e545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mazaheri, E.; Ghahramanian, A.; Valizadeh, L.; Zamanzadeh, V.; Onyeka, T.C. Disrupted mothering in Iranian mothers with breast cancer: A hybrid concept analysis. BMC Women’s Health 2021, 21, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.N.; Kesic, V.I.; Van Calsteren, K.; Petkovic, S.; Amant, F. Cancer in pregnancy: A survey of current clinical practice. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013, 167, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambertini, M.; Di Maio, M.; Pagani, O.; Demeestere, I.; Del Mastro, L.; Loibl, S.; Partridge, A.H.; Azim, H.H.; Peccatori, F.A. A survey on physicians’ knowledge, practice and attitudes on fertility and pregnancy issues in young breast cancer patients. Breast 2017, 32 (Suppl. 1), S85–S86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambertini, M.; Di Maio, M.; Poggio, F.; Pagani, O.; Curigliano, G.; Del Mastro, L.; Paluch-Shimon, S.; Loibl, S.; Partridge, A.H.; Azim, H.A.; et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practice of physicians towards fertility and pregnancy-related issues in young BRCA-mutated breast cancer patients. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2019, 38, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, S.; Young, A. The experiences and perceptions of women diagnosed with breast cancer during pregnancy. Asia-Pacific J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 3, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Malignancy | Modes of Treatment | Considerations for Pregnant Patients | Considerations for the Foetus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer [19,20] | Surgery (safe throughout pregnancy), radiotherapy (contraindicated in pregnancy), chemotherapy (second and third trimester), hormonal/endocrine therapy (contraindicated), immunotherapy (contraindicated, PD-1/PD-L1 pathway could result in immune response against the foetus), targeted therapy (contraindicated with exception of trastuzumab, which may be used in the first trimester under close monitoring). | Physiological breast changes should be considered, delaying reconstruction surgery after delivery. Higher risk of pregnancy complication cannot be excluded. | Increased risks of stillbirths, small gestational weight, preterm delivery, neonatal mortality. No significant impairment after exposure to chemotherapy. Prematurity correlated with worse cognitive outcome irrespective of cancer treatment. |

| Thyroid cancer [21,22] | Surgery (second trimester or after delivery), endocrine therapy (LT4 therapy should start immediately after surgery), radioactive iodine (contraindicated in pregnancy and breastfeeding), immunotherapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) is not well studied. | Calcium and vitamin D supplementation, hypothyroidism should be avoided by correct supplementation of thyroxine. No evidence to support pregnancy termination. | Thyroid hormone deficiency can cause severe neurological disorders. |

| Cervical cancer [7,23,24] | Hysterectomy (in advanced cases, can be combined with a caesarean delivery or performed post-partum, otherwise not compatible with pregnancy), cold knife conization (risk of premature birth), radical trachelectomy/cervicectomy (risk of premature birth), chemotherapy (second and third trimester), radiotherapy (contraindicated). | Caesarean section is preferred delivery method, especially in advanced cases. Fertility preservation in advanced cases might not be possible. Chemotherapy is not recommended beyond 35 weeks of gestation to allow maternal and foetal bone marrow recovery before delivery. | Chemotherapy can affect foetal eyes, genitals, hematopoietic system, nervous system, foetal growth. Single cases of bilateral hearing loss and rhabdomyosarcoma have been reported. |

| Other gynaecological cancers (vulvar, vaginal, endometrial, ovarian cancer, ovarian masses with low malignant potential) [7] | Laparoscopic surgery (feasible throughout pregnancy, not longer than 90–120 min), surgery (decided upon individual cases), chemotherapy (second and third trimester), radiotherapy (contraindicated), systemic therapies not well studied. | Caesarean section is a preferred delivery method, especially in advanced cases. In cases of advanced epithelial ovarian cancer, pregnancy termination should be considered in the first half of pregnancy. Chemotherapy is not recommended beyond 35 weeks of gestation to allow maternal and foetal bone marrow recovery before delivery. | If possible, delivery should not be induced before 37 weeks to allow foetal maturity. Breastfeeding should be avoided with ongoing chemotherapeutic, endocrine and targeted treatment. |

| Lymphomas (Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma) [25,26] | Chemotherapy (second and third trimester), radiotherapy (conflicting data), immunotherapy (limited data) | Deferring therapy until after delivery does not always affect maternal outcomes and can be considered. Pregnancy termination can be considered in the first trimester. Patients receiving antenatal therapy have more obstetric complications (preterm contractions and preterm rupture of membranes). | No gross foetal malformations or anomalies have been reported. Low gestational age and admissions to NICU did not differ between neonates exposed and not exposed to chemotherapy. Those exposed to chemotherapy had lower birth weight. |

| Melanoma [27,28] | Excisions (throughout pregnancy—safe and necessary), targeted therapies (BRAF inhibitors) and checkpoint inhibitors (anti-PD1 and anti-CTLA4) may be teratogenic. | Relationship between pregnancy and melanoma should not be ruled out. Some reports suggest poorer prognosis for pregnant patients, but evidence is inconclusive. | No evidence that melanoma diagnosis will have adverse effected on the foetus. Melanoma accounts for 30% of metastatic spread to the placenta. This does not mean that the foetus will be affected. |

| Brain tumours [29,30] | Surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy—only limited data available due to rarity of the condition. | Delivery recommended after 34 weeks of gestation to allow foetal maturity. Caesarean delivery recommended. | No known foetal complications. Steroids for foetal lung maturation might be needed if early delivery is needed due to deteriorating maternal condition. |

| Lung cancer [31,32] | Chemotherapy (second and third trimester), targeted therapies—only limited data available due to rarity of the condition | Increased risk of lung infections. Case reports suggest that lung cancer is diagnosed at advanced stages in pregnancy and prognosis is poor. | No adverse outcomes data reported. Due to advanced stage of maternal cancer, there might be a metastatic spread to the placenta. This does not mean that the foetus will be affected. |

| Discussion Themes: Ethical, Patient-Centred Care of Pregnant Cancer Patients |

|---|

| Recognising relational context of individual patient’s autonomy and supporting it through caring, patient-focused approach to build trusted relationships between the pregnant cancer patient and the healthcare team |

| Balancing maternal and foetal beneficence can be supported by caring, patient-focused and maternalistic approach to patient care with best interest of the patient and their foetus in mind |

| Balancing maternalistic and relational approach with evidence-based, personalised patient care while attempting to understand individual realities of pregnant cancer patient |

| Considering protection of the vulnerable in a light of responsibilities towards the unborn child and underrepresented stakeholders, such as other children of a pregnant cancer patient and pregnant patients themselves |

| Ensuring reasonable and just resource allocation to avoid giving pregnant cancer patient false hopes and creating futile financial burdens |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Linkeviciute, A.; Canario, R.; Peccatori, F.A.; Dierickx, K. Caring for Pregnant Patients with Cancer: A Framework for Ethical and Patient-Centred Care. Cancers 2024, 16, 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16020455

Linkeviciute A, Canario R, Peccatori FA, Dierickx K. Caring for Pregnant Patients with Cancer: A Framework for Ethical and Patient-Centred Care. Cancers. 2024; 16(2):455. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16020455

Chicago/Turabian StyleLinkeviciute, Alma, Rita Canario, Fedro Alessandro Peccatori, and Kris Dierickx. 2024. "Caring for Pregnant Patients with Cancer: A Framework for Ethical and Patient-Centred Care" Cancers 16, no. 2: 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16020455

APA StyleLinkeviciute, A., Canario, R., Peccatori, F. A., & Dierickx, K. (2024). Caring for Pregnant Patients with Cancer: A Framework for Ethical and Patient-Centred Care. Cancers, 16(2), 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16020455