Iron Overload in Children with Acute Lymphoblastic and Acute Myeloblastic Leukemia—Experience of One Center

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Laboratory Tests

2.3. Blood Transfusion

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

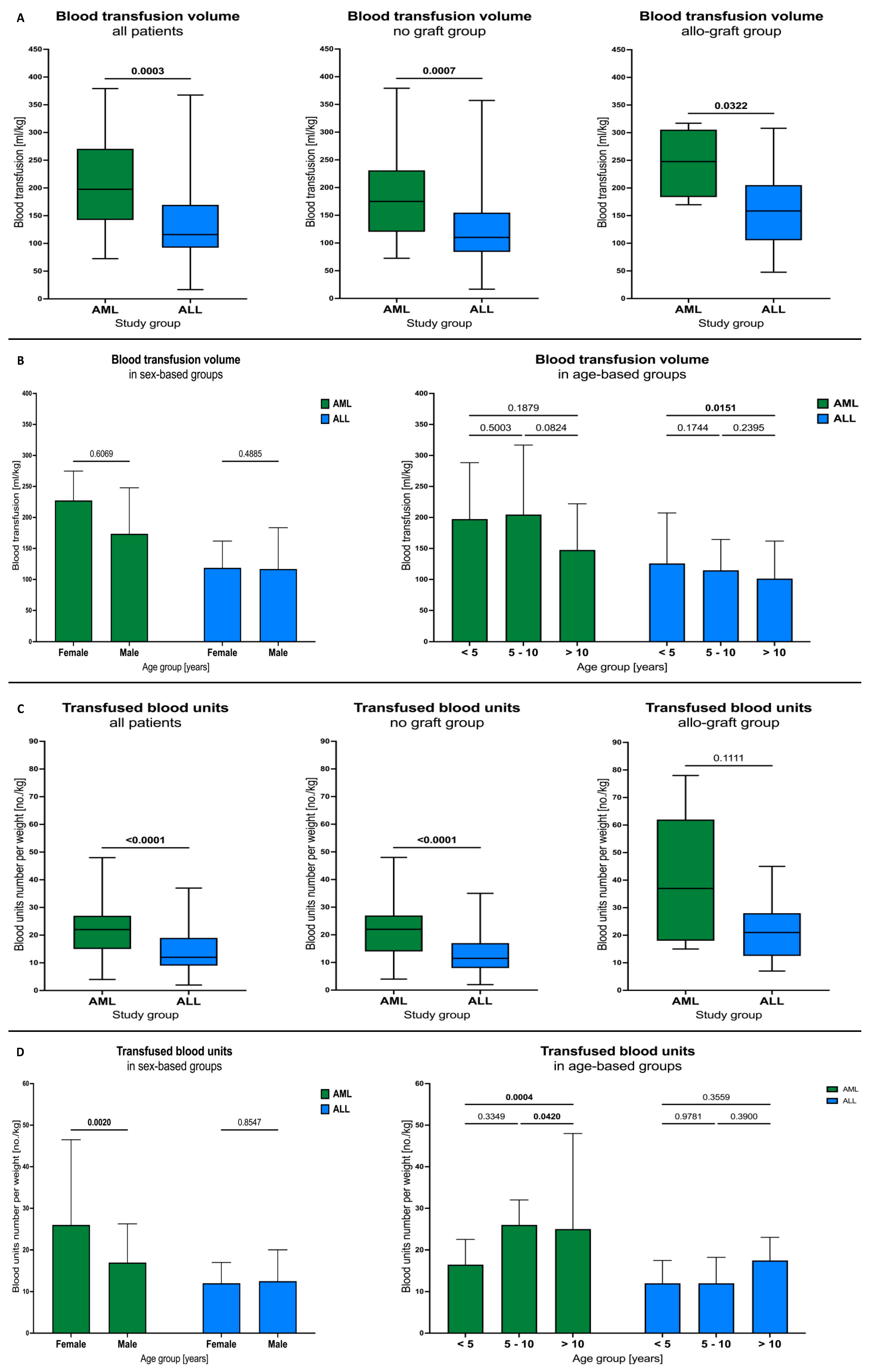

3.1. Blood Transfusions

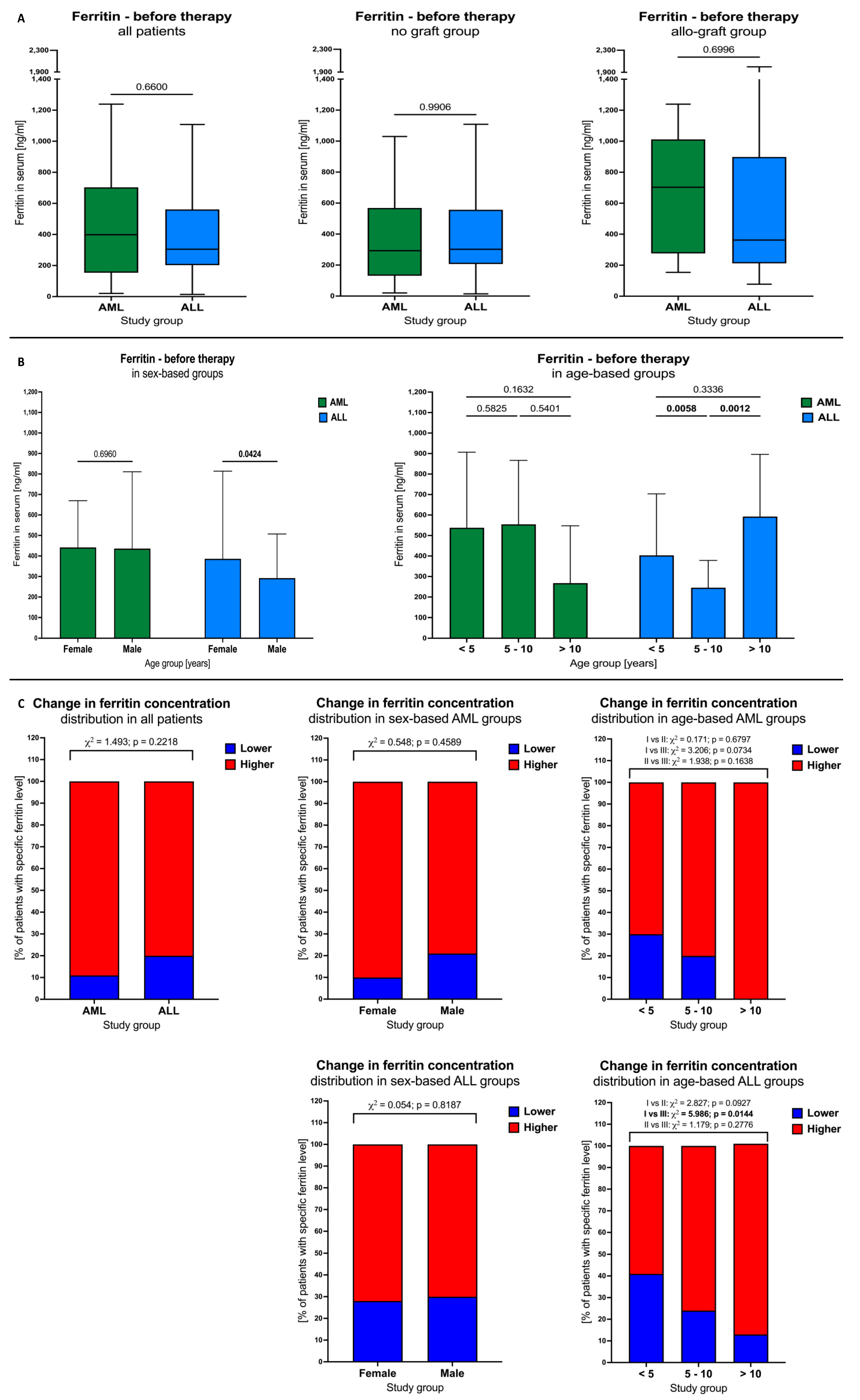

3.2. Ferritin Levels in AML and ALL Patients before Therapy

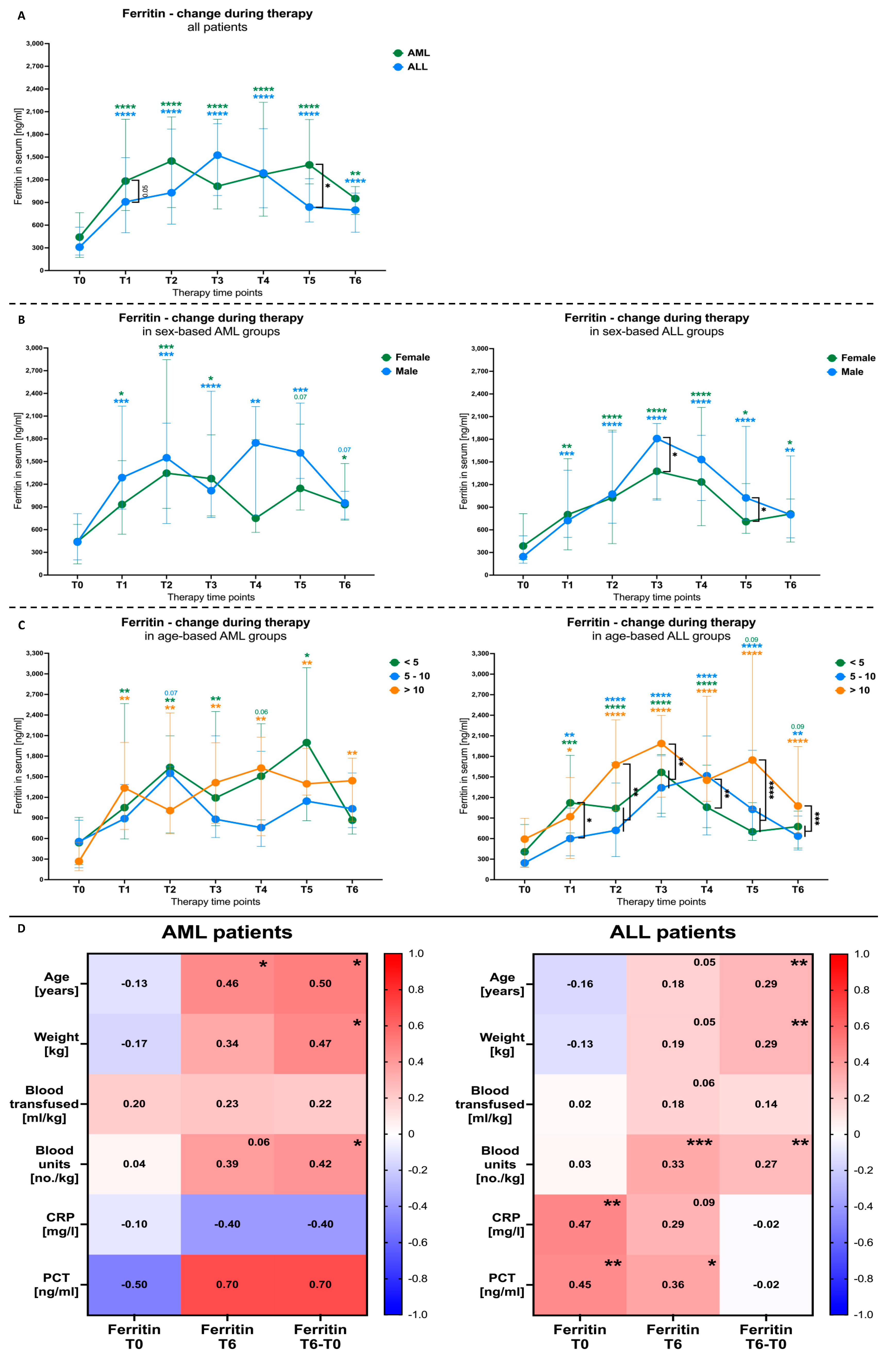

3.3. Blood Transfusion Effects on Ferritin Levels in AML and ALL Patients

3.4. Blood Transfusion Volumes and Units among AML and ALL Patients

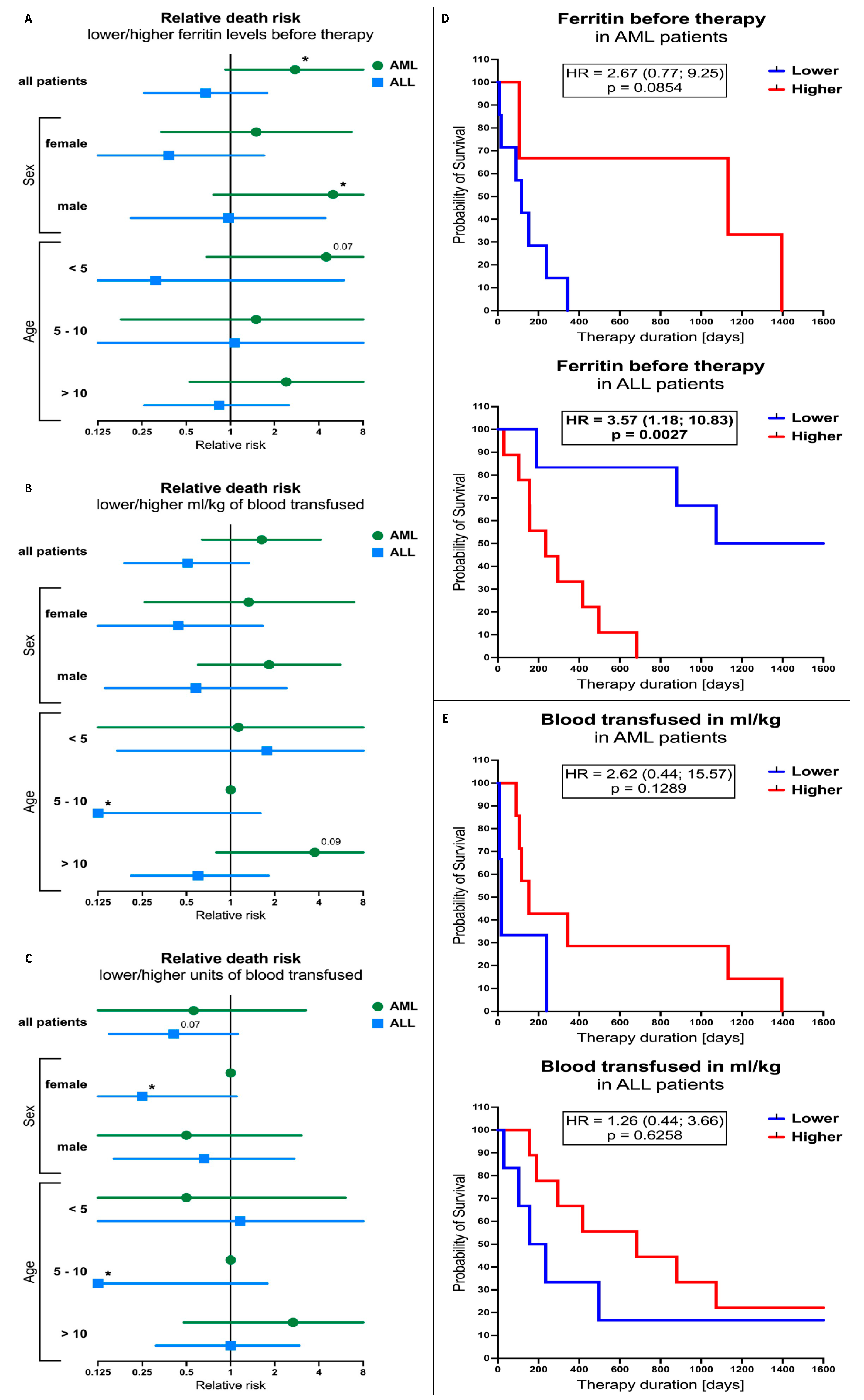

3.5. Ferritin Levels and Blood-Transfusion-Related Parameters Influence on the Outcome of the AML and ALL Patients’ Therapy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alkhateeb, A.A.; Connor, J.R. The Significance of Ferritin in Cancer: Anti-Oxidation, Inflammation and Tumorigenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1836, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słomka, A.; Zekanowska, E.; Piotrowska, K.; Kwapisz, J. Iron Metabolism and Maternal-Fetal Iron Circulation. Adv. Hyg. Exp. Med. 2012, 66, 876–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arosio, P.; Elia, L.; Poli, M. Ferritin, Cellular Iron Storage and Regulation. IUBMB Life 2017, 69, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halonen, P.; Mattila, J.; Suominen, P.; Ruuska, T.; Salo, M.K.; Mäkipernaa, A. Iron Overload in Children Who Are Treated for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Estimated by Liver Siderosis and Serum Iron Parameters. Pediatrics 2003, 111, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastaniah, W.; Harmatz, P.; Pakbaz, Z.; Fischer, R.; Vichinsky, E.; Walters, M.C. Transfusional Iron Burden and Liver Toxicity after Bone Marrow Transplantation for Acute Myelogenous Leukemia and Hemoglobinopathies. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2008, 50, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moroz, V.; Machin, D.; Hero, B.; Ladenstein, R.; Berthold, F.; Kao, P.; Obeng, Y.; Pearson, A.D.J.; Cohn, S.L.; London, W.B. The Prognostic Strength of Serum LDH and Serum Ferritin in Children with Neuroblastoma: A Report from the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group (INRG) Project. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2020, 67, e28359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, A. Serum Ferritin and Malignant Tumours. Med. Oncol. Tumor Pharmacother. 1984, 1, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unal, S.; Cetin, M.; Hazirolan, T.; Yildirim, G.; Meral, A.; Birbilen, A.; Karabulut, E.; Aytac, S.; Tavil, B.; Kuskonmaz, B.; et al. Number of Erythrocyte Transfusions Is More Predictive than Serum Ferritin in Estimation of Cardiac Iron Loading in Pediatric Patients with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Leuk. Res. 2014, 38, 882–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, G.R. Blood Transfusions in Children with Cancer and Hematologic Disorders: Why, When, and How? Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2005, 44, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, J.B. Practical Management of Iron Overload. Br. J. Haematol. 2001, 115, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, J.; Fish, J.D. Insidious Iron Burden in Pediatric Patients with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2011, 56, 368–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivieri, N.F. Progression of Iron Overload in Sickle Cell Disease. Semin. Hematol. 2001, 38, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inati, A.; Musallam, K.M.; Wood, J.C.; Taher, A.T. Iron Overload Indices Rise Linearly with Transfusion Rate in Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. Blood 2010, 115, 2980–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majhail, N.S.; DeFor, T.E.; Lazarus, H.M.; Burns, L.J. Iron-Overload after Autologous Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Leuk. Res. 2009, 33, 578–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellström-Lindberg, E. Management of Anemia Associated with Myelodysplastic Syndrome. Semin. Hematol. 2005, 42, S10–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimeh, N.; Bishop, R.C. Disorders of Iron Metabolism. Med. Clin. North Am. 1980, 64, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G.J.; Vulpe, C.D. Mammalian Iron Transport. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2009, 66, 3241–3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydinok, Y.; Darcan, S.; Polat, A.; Kavakli, K.; Nişli, G.; Çoker, M.; Kantar, M.; Çetingul, N. Endocrine Complications in Patients with Beta-Thalassemia Major. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2002, 48, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Borgna-Pignatti, C.; Cappellini, M.D.; de Stefano, P.; del Vecchio, G.C.; Forni, G.L.; Gamberini, M.R.; Ghilardi, R.; Origa, R.; Piga, A.; Romeo, M.A.; et al. Survival and Complications in Thalassemia. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005, 1054, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennell, D.J. T2* Magnetic Resonance and Myocardial Iron in Thalassemia. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005, 1054, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michon, J. Incidence of Anemia in Pediatric Cancer Patients in Europe: Results of a Large, International Survey. Med. Pediatr. Oncol. 2002, 39, 448–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łęcka, M.; Słomka, A.; Albrecht, K.; Żekanowska, E.; Romiszewski, M.; Styczyński, J. Unbalance in Iron Metabolism in Childhood Leukemia Converges with Treatment Intensity: Biochemical and Clinical Analysis. Cancers 2021, 13, 3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mainous, A.G.; Gill, J.M.; Everett, C.J. Transferrin Saturation, Dietary Iron Intake, and Risk of Cancer. Ann. Fam. Med. 2005, 3, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, R.G.; Jones, D.Y.; Micozzi, M.S.; Taylor, P.R. Body Iron Stores and the Risk of Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988, 319, 1047–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D.; Culligan, D.; Jowitt, S.; Kelsey, S.; Mufti, G.; Oscier, D.; Parker, J. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Therapy of Adult Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Br. J. Haematol. 2003, 120, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, E.; Kantarjian, H.M.; Koller, C.; Taher, A. Red Blood Cell Transfusions and Iron Overload in the Treatment of Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Cancer 2008, 112, 1089–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovillion, E.M.; Schubert, L.; Dietz, A.C. Iron Overload in Survivors of Childhood Cancer. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 40, 396–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.C. Estimating Tissue Iron Burden: Current Status and Future Prospects. Br. J. Haematol. 2015, 170, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nottage, K.; Gurney, J.G.; Smeltzer, M.; Castellanos, M.; Hudson, M.M.; Hankins, J.S. Trends in Transfusion Burden among Long-Term Survivors of Childhood Hematological Malignancies. Leuk. Lymphoma. 2013, 54, 1719–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, D.M.; Zinberg, N. Measurement of Serum Ferritin by Radioimmunoassay: Results in Normal Individuals and Patients with Breast Cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1975, 55, 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.A.E.; Miller, F.M.; Worwood, M.; Jacobs, A. Ferritinaemia in Leukaemia and Hodgkin’s Disease. Br. J. Cancer 1973, 27, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tappin, J.A.; George, W.D.; Bellingham, A.J. Effect of Surgery on Serum Ferritin Concentration in Patients with Breast Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 1979, 40, 658–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxim, P.E.; Veltri, R.W. Serum Ferritin as a Tumor Marker in Patients with Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. Cancer 1986, 57, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melia, W.M.; Bullock, S.; Johnson, P.J.; Williams, R. Serum Ferritin in Hepatocellular Carcinoma A Comparison with Alphafetoprotein. Cancer 1983, 51, 2112–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niitsu, Y.; Kohgo, Y.; Yokota, M.; Urushizaki, I. Radioimmunoassay of Serum Ferritin in Patients with Malignancy. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1975, 259, 450–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson Chornenki, N.L.; James, T.E.; Barty, R.; Liu, Y.; Rochwerg, B.; Heddle, N.M.; Siegal, D.M. Blood Loss from Laboratory Testing, Anemia, and Red Blood Cell Transfusion in the Intensive Care Unit: A Retrospective Study. Transfusion 2020, 60, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sait, S.; Zaghloul, N.; Patel, A.; Shah, T.; Iacobas, I.; Calderwood, S. Transfusion Related Iron Overload in Pediatric Oncology Patients Treated at a Tertiary Care Centre and Treatment with Chelation Therapy. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2014, 61, 2319–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.H.; Kim, J.W.; Rhee, J.Y.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, B.S.; Kim, I.; Bang, S.M.; Yoon, S.S.; Lee, J.S.; Han, K.S.; et al. Cost analysis of iron-related complications in a single institute. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2009, 24, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihlow, J.; Gross, S.; Sick, A.; Schneider, T.; Flörcken, A.; Burmeister, T.; Türkmen, S.; Arnold, R.; Dörken, B.; Westermann, J. AML: High serum ferritin at initial diagnosis has a negative impact on long-term survival. Leuk. Lymphoma. 2019, 60, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulbert, E.; Schmidt, C.G. Ferritin—A Tumor Marker in Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Detect. Prev. 1985, 8, 297–302. [Google Scholar]

- Cacciotti, C.; Athale, U. Transfusion-Related Iron Overload in Children with Leukemia. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 43, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruccione, K.S.; Wood, J.C.; Sposto, R.; Malvar, J.; Chen, C.; Freyer, D.R. Characterization of Transfusion-Derived Iron Deposition in Childhood Cancer Survivors. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers. Prev. 2014, 23, 1913–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneeweiss-Gleixner, M.; Greiner, G.; Herndlhofer, S.; Schellnegger, J.; Krauth, M.-T.; Gleixner, K.V.; Wimazal, F.; Steinhauser, C.; Kundi, M.; Thalhammer, R.; et al. Impact of HFE Gene Variants on Iron Overload, Overall Survival and Leukemia-Free Survival in Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2021, 11, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ktena, Y.P.; Athanasiadou, A.; Lambrou, G.; Adamaki, M.; Moschovi, M. Iron Chelation with Deferasirox for the Treatment of Secondary Hemosiderosis in Pediatric Oncology Patients: A Single-Center Experience. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2013, 35, 447–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scoglio, M.; Cappellini, M.D.; D’angelo, E.; Bianchetti, M.G.; Lava, S.A.G.; Agostoni, C.; Milani, G.P. Kidney Tubular Damage Secondary to Deferasirox: Systematic Literature Review. Children 2021, 8, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amid, A.; Barrowman, N.; Vijenthira, A.; Lesser, P.; Mandel, K.; Ramphal, R. Risk Factors for Hyperferritinemia Secondary to Red Blood Cell Transfusions in Pediatric Cancer Patients. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2013, 60, 1671–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecka, M.; Czyzewski, K.; Debski, R.; Wysocki, M.; Styczynski, J. Impact of Ferritin Serum Concentration on SurvivalImpact of Ferritin Serum Concentration on Survival in Children with Acute Leukemia: A Long-Term Follow-up in Children with Acute Leukemia: A Long-Term Follow-up. Acta Haematol. Pol. 2021, 52, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| LEUKEMIAS | ALL * | AML ** | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Males (M) | Females (F) | Total | M | F | Total | M | F | |

| n | 135 | 77 | 58 | 110 | 64 | 46 | 35 | 23 | 12 |

| % | 100 | 57.03 | 42.97 | 100 | 58.2 | 41.82 | 100 | 65.71 | 34.28 |

| Median (years) | 5.62 yrs | 6078 | 8127 | ||||||

| 0.06–17.6 | |||||||||

| (a) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGE GROUPS | ||||||

| ≤1 yr Group 1 | 1–5 yrs Group 2 | 5–10 yrs Group 3 | ≥10 yrs Group 4 | |||

| Total | 8 8/135 30.06% | 51 51/135 37.78% | 43 43/135 31.85% | 33 33/135 24.44% | ||

| ALL | 3 3/110 2.72% | 46 46/110 41.81% | 38 38/110 | 23 23/110 21.82% | ||

| AML | 5 5/25 20% | 5 5/25 20% | 5 5/25 20% | 10 10/25 40% | ||

| (b) | ||||||

| Protocol | n | Allo HSCT | REC | Deceased | Second Malignancy | |

| ALL | ALLIC 2009 | 51 | 25 | 4 | 9 | 1 |

| ALLIC 2012 | 59 | |||||

| AML | AML BFM 2002 | 25 | 23 | 4 | 10 | 0 |

| Median | Mean * | SD * | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LEUKEMIAS (n = 135) | |||||

| 3300 | 4311.67 | 3443.45 | 360 | 23,400 |

| 128.6 | 171.29 | 173.65 | 16.7 | 1800 |

| 14 | 17.62 | 11.99 | 2 | 78 |

| ALL (n = 110) | |||||

| 3300 | 3869 | 2624 | 360 | 11,100 |

| 121.4 | 150.4 | 103.1 | 16.70 | 532.9 |

| 12 | 15.79 | 10.13 | 2 | 49 |

| AML (n = 35) | |||||

| 5035 | 6359 | 5552 | 725.0 | 23,400 |

| 201.2 | 267.8 | 336.2 | 72.50 | 1800 |

| 22.50 | 26.08 | 16.01 | 4 | 78 |

| Serum Ferritin Start >500 ng/mL n | Median | Serum Ferritin Finish >500 ng/mL n | Median | Same Patients n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total 55 55/135 (40.74%) ALL 44/110 (40%) AML 11/25 (44%) | 889 712–963 | Total 108 110/135 (80%) ALL 86/110 (78.18%) AML 24/25 (96%) | 933.7 500.1–4945 | 53 (96.35%) |

| Serum Ferritin Start >1000 ng/mL n | Median Min–Max | Serum Ferritin Finish >1000 ng/mL n | Median Min–max | Same Patients n |

| Total 19 19/135 (14.07%) ALL 16/110 (14.54%) AML 3/25 (12%) | 1692 1097–2127 | Total 42 42/135 (31.11%) ALL 31/110 (28.18%) AML 11/25 (44%) | 1589 1001–4945 | 14 (73.68%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sawicka-Zukowska, M.; Kretowska-Grunwald, A.; Kania, A.; Topczewska, M.; Niewinski, H.; Bany, M.; Grubczak, K.; Krawczuk-Rybak, M. Iron Overload in Children with Acute Lymphoblastic and Acute Myeloblastic Leukemia—Experience of One Center. Cancers 2024, 16, 367. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16020367

Sawicka-Zukowska M, Kretowska-Grunwald A, Kania A, Topczewska M, Niewinski H, Bany M, Grubczak K, Krawczuk-Rybak M. Iron Overload in Children with Acute Lymphoblastic and Acute Myeloblastic Leukemia—Experience of One Center. Cancers. 2024; 16(2):367. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16020367

Chicago/Turabian StyleSawicka-Zukowska, Malgorzata, Anna Kretowska-Grunwald, Agnieszka Kania, Magdalena Topczewska, Hubert Niewinski, Marcin Bany, Kamil Grubczak, and Maryna Krawczuk-Rybak. 2024. "Iron Overload in Children with Acute Lymphoblastic and Acute Myeloblastic Leukemia—Experience of One Center" Cancers 16, no. 2: 367. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16020367

APA StyleSawicka-Zukowska, M., Kretowska-Grunwald, A., Kania, A., Topczewska, M., Niewinski, H., Bany, M., Grubczak, K., & Krawczuk-Rybak, M. (2024). Iron Overload in Children with Acute Lymphoblastic and Acute Myeloblastic Leukemia—Experience of One Center. Cancers, 16(2), 367. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16020367