Local Therapy and Reconstruction in Penile Cancer: A Review

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

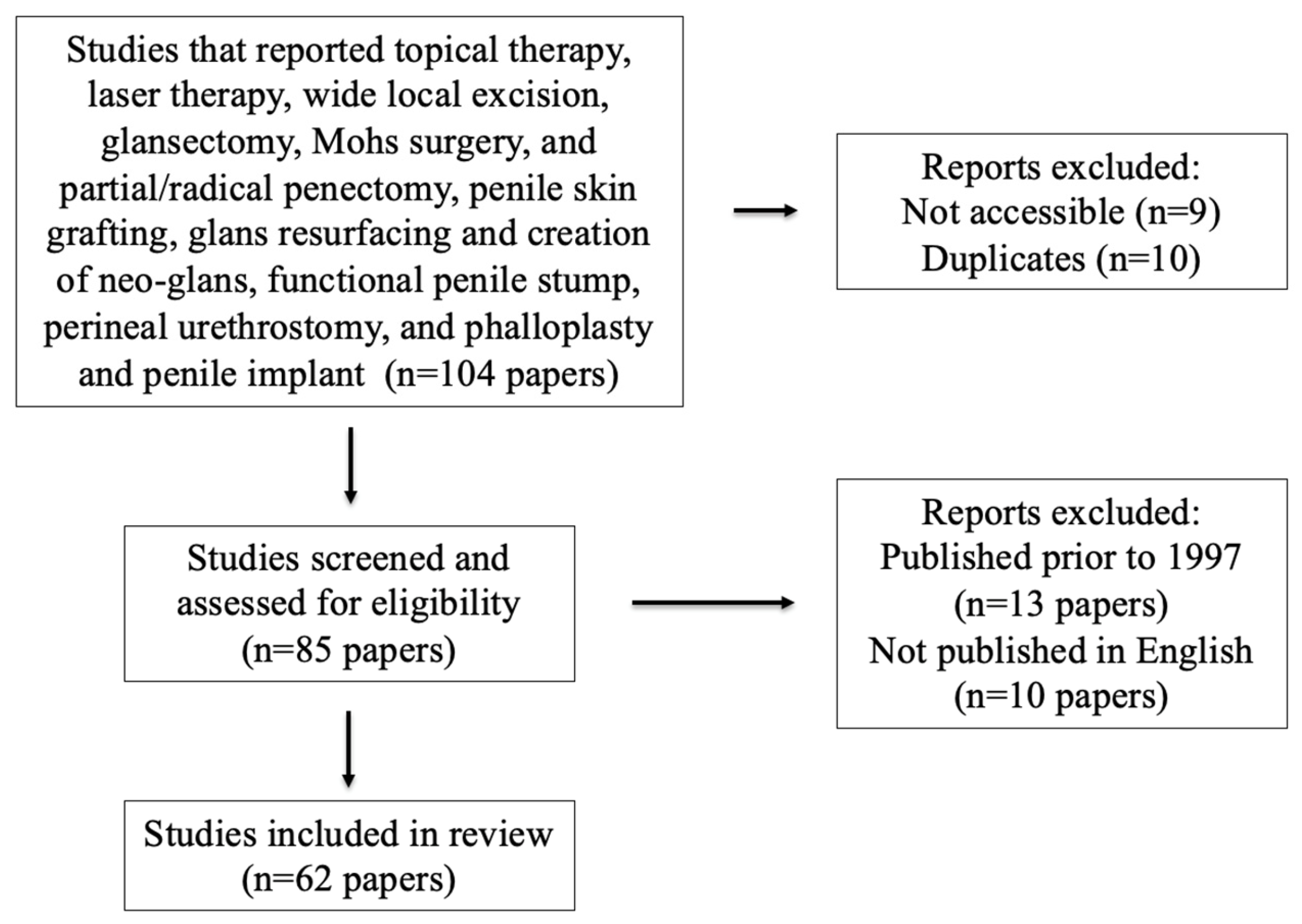

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Primary Therapy

3.1.1. Topical Therapy

3.1.2. Laser Therapy

3.1.3. Wide Local Excision

3.1.4. Glansectomy

3.1.5. Mohs Surgery

3.1.6. Radiation Therapy

3.1.7. Partial/Radical Penectomy

3.2. Reconstructive Techniques

3.2.1. Penile Skin Grafting

3.2.2. Glans Resurfacing and Creation of Neo-Glans

3.2.3. Creation of Functional Penile Stump

3.2.4. Perineal Urethrostomy

3.2.5. Phalloplasty and Penile Implant

4. Methodological Challenges and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, B.Y.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.; German, R.R.; Giuliano, A.; Goodman, M.T.; King, J.B.; Negoita, S.; Villalon-Gomez, J.M. Burden of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the penis in the United States, 1998–2003. Cancer 2008, 113, 2883–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attalla, K.; Paulucci, D.J.; Blum, K.; Anastos, H.; Moses, K.A.; Badani, K.K.; Spiess, P.E.; Sfakianos, J.P. Demographic and socioeconomic predictors of treatment delays, pathologic stage, and survival among patients with penile cancer: A report from the National Cancer Database. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2018, 36, 14.e17–14.e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakenberg, O.W.; Dräger, D.L.; Erbersdobler, A.; Naumann, C.M.; Jünemann, K.-P.; Protzel, C. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Penile Cancer. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt Int. 2018, 115, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinlen, J.E.; Buethe, D.D.; Culkin, D.J. Advanced penile cancer. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2012, 44, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchioni, M.; Berardinelli, F.; De Nunzio, C.; Spiess, P.; Porpiglia, F.; Schips, L.; Cindolo, L. New insight in penile cancer. Minerva Urol. Nefrol. 2018, 70, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddineni, S.B.; Lau, M.M.; Sangar, V. Identifying the needs of penile cancer sufferers: A systematic review of the quality of life, psychosexual and psychosocial literature in penile cancer. BMC Urol. 2009, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamel, M.H.; Bissada, N.; Warford, R.; Farias, J.; Davis, R. Organ Sparing Surgery for Penile Cancer: A Systematic Review. J. Urol. 2017, 198, 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irizarry, V.M.T.; Paster, I.C.; Ogbuji, V.; Gomez, D.M.; Mccormick, K.; Chipollini, J. Improving Quality of Life and Psychosocial Health for Penile Cancer Survivors: A Narrative Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaig, T.; Spiess, P.; Abern, M.; Agarwal, N.; Bangs, R.; Buyyounouski, M.; Chan, K.; Chang, S.; Friedlander, T.; Greenberg, R.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® insights: Bladder cancer, version 2.2022: Featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2022, 20, 866–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippou, P.; Shabbir, M.; Malone, P.; Nigam, R.; Muneer, A.; Ralph, D.J.; Minhas, S. Conservative Surgery for Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Penis: Resection Margins and Long-Term Oncological Control. J. Urol. 2012, 188, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajiran, A.; Zemp, L.; Aydin, A.M.; Cheryian, S.K.; Pow-Sang, J.M.; Chahoud, J.; Spiess, P.E. Topical chemotherapy for penile carcinoma in situ: Contemporary outcomes and reported toxicity. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2021, 39, 72.e1–72.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristiansen, S.; Torbrand, C.; Svensson, Å.; Forslund, O.; Bjartling, C. Incidence of penile intraepithelial neoplasia and treatment strategies in Sweden 2000–2019. BJU Int. 2022, 129, 752–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manjunath, A.; Brenton, T.; Wylie, S.; Corbishley, C.M.; Watkin, N.A. Topical Therapy for non-invasive penile cancer (Tis)—Updated results and toxicity. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2017, 6, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babbar, P.; Yerram, N.; Crane, A.; Sun, D.; Ericson, K.; Sun, A.; Khanna, A.; Wood, H.; Stephenson, A.; Angermeier, K. Penile-sparing modalities in the management of low-stage penile cancer. Urol. Ann. 2018, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torelli, T.; Catanzaro, M.A.; Nicolai, N.; Giannatempo, P.; Necchi, A.; Raggi, D.; Paolini, B.; Colecchia, M.; Piva, L.; Biasoni, D.; et al. Treatment of Carcinoma In Situ of the Glans Penis With Topical Imiquimod Followed by Carbon Dioxide Laser Excision. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2017, 15, e483–e487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandieramonte, G.; Colecchia, M.; Mariani, L.; Vullo, S.L.; Pizzocaro, G.; Piva, L.; Nicolai, N.; Salvioni, R.; Lezzi, V.; Stefanon, B.; et al. Peniscopically Controlled CO2 Laser Excision for Conservative Treatment of In Situ and T1 Penile Carcinoma: Report on 224 Patients. Eur. Urol. 2008, 54, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, D.H.; Yan, S.; Ottenhof, S.R.; Draeger, D.; Baumgarten, A.S.; Chipollini, J.; Protzel, C.; Zhu, Y.; Ye, D.; Hakenberg, O.W.; et al. Laser ablation as monotherapy for penile squamous cell carcinoma: A multi-center cohort analysis. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2018, 36, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragonese, M.; Dibitetto, F.; Bassi, P.; Pinto, F. Laser technology in urologic oncology. Urol. J. 2022, 89, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musi, G.; Russo, A.; Conti, A.; Mistretta, F.A.; Di Trapani, E.; Luzzago, S.; Bianchi, R.; Renne, G.; Ramoni, S.; Ferro, M.; et al. Thulium–yttrium–aluminium–garnet (Tm:YAG) laser treatment of penile cancer: Oncological results, functional outcomes, and quality of life. World J. Urol. 2018, 36, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, R.P.; Boon, T.A.; Van Venrooij, G.E.P.M.; Wijburg, C.J. Long-Term Follow-up after Laser Therapy for Penile Carcinoma. Urology 2007, 69, 759–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windahl, T.; Andersson, S.-O. Combined Laser Treatment for Penile Carcinoma: Results after Long-Term Followup. J. Urol. 2003, 169, 2118–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windahl, T.; Skeppner, E.; Andersson, S.-O.; Fugl-Meyer, K.S. Sexual Function and Satisfaction in Men after Laser Treatment for Penile Carcinoma. J. Urol. 2004, 172, 648–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, E.; Yao, H.H.; Chee, J. Optimal surgical margin for penile-sparing surgery in management of penile cancer—Is 2 cm really necessary? BJUI Compass 2021, 2, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedigh, O.; Falcone, M.; Ceruti, C.; Timpano, M.; Preto, M.; Oderda, M.; Kuehhas, F.; Sibona, M.; Gillo, A.; Gontero, P.; et al. Sexual function after surgical treatment for penile cancer: Which organ-sparing approach gives the best results? Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2015, 9, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cilio, S.; Tufano, A.; Pezone, G.; Alvino, P.; Spena, G.; Pandolfo, S.D.; Del Prete, P.; Amato, C.; Damiano, R.; Salonia, A.; et al. Sexual Outcomes after Conservative Management for Patients with Localized Penile Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 10501–10508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sosnowski, R.; Kuligowski, M.; Kuczkiewicz, O.; Moskal, K.; Wolski, J.K.; Bjurlin, M.A.; Wysock, J.S.; Pęczkowski, P.; Protzel, C.; Demkow, T. Primary penile cancer organ sparing treatment. Cent. Eur. J. Urol. 2016, 69, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgarten, A.; Chipollini, J.; Yan, S.; Ottenhof, S.R.; Tang, D.H.; Draeger, D.; Protzel, C.; Zhu, Y.; Ye, D.; Hakenberg, O.W.; et al. Penile Sparing Surgery for Penile Cancer: A Multicenter International Retrospective Cohort. J. Urol. 2018, 199, 1233–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, Y.; Hadway, P.; Biedrzycki, O.; Perry, M.J.A.; Corbishley, C.; Watkin, N.A. Reconstructive Surgery for Invasive Squamous Carcinoma of the Glans Penis. Eur. Urol. 2007, 52, 1179–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakalis, V.I.; Campi, R.; Barreto, L.; Garcia-Perdomo, H.A.; Greco, I.; Zapala, Ł.; Kailavasan, M.; Antunes-Lopes, T.; Marcus, J.D.; Manzie, K.; et al. What Is the Most Effective Management of the Primary Tumor in Men with Invasive Penile Cancer: A Systematic Review of the Available Treatment Options and Their Outcomes. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2022, 40, 58–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coddington, N.D.; Redger, K.D.; Higuchi, T.T. Surgical principles of penile cancer for penectomy and inguinal lymph node dissection: A narrative review. AME Med. J. 2021, 6, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohs, F.; Snow, S.; Messing, E.; Kuglitsch, M. Microscopically controlled surgery in the treatment of carcinoma of the penis. J. Urol. 1985, 133, 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcalá, N.E.; Reines, K.L.; Merritt, B.; Figler, B.D.; Bjurlin, M.A. Mohs microsurgery for localized penile carcinoma: 10 year retrospective review of local recurrence rates and surgical complications. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2022, 40, 457.e1–457.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brkovic, D.; Kalble, T.; Dorsam, J.; Baruah, S.; Lotzerich, C.; Banafsche, R.; Riedasch, G.; Staehler, G. Surgical treatment of invasive penile cancer—The Heidelberg experience from 1968 to 1994. Eur. Urol. 1997, 31, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeratterapillay, R.; Teo, L.; Asterling, S.; Greene, D. Oncologic Outcomes of Penile Cancer Treatment at a UK Supraregional Center. Urology 2015, 85, 1097–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djajadiningrat, R.S.; Van Werkhoven, E.; Meinhardt, W.; Van Rhijn, B.W.G.; Bex, A.; Van Der Poel, H.G.; Horenblas, S. Penile Sparing Surgery for Penile Cancer—Does it Affect Survival? J. Urol. 2014, 192, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindner, A.K.; Schachtner, G.; Steiner, E.; Kroiss, A.; Uprimny, C.; Steinkohl, F.; Horninger, W.; Heidegger, I.; Madersbacher, S.; Pichler, R. Organ-sparing surgery of penile cancer: Higher rate of local recurrence yet no impact on overall survival. World J. Urol. 2020, 38, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prohaska, J.; Cook, C. Skin Grafting. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Junco, P.T.; Dore, M.; Cerezo, V.N.; Gomez, J.J.; Ferrero, M.M.; González, M.D.; Lopez-Pereira, P.; Lopez-Gutierrez, J. Penile Reconstruction with Skin Grafts and Dermal Matrices: Indications and Management. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. Rep. 2017, 05, e47–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, M.; Preto, M.; Blecher, G.; Timpano, M.; Peretti, F.; Ferro, I.; Mangione, C.; Gontero, P. The Outcomes of Glansectomy and Split Thickness Skin Graft Reconstruction for Invasive Penile Cancer Confined to Glans. Urology 2022, 165, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, H.; Zheng, D.; Ni, J.; Wan, X.; Wang, Z. MP33-09 Glansectomy and Neoglans Reconstruction Using Split-Thickness Skin Graft/Acellular Dermal Matrix for Penile Cancer. J. Urol. 2023, 209, e453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beech, B.B.; Chapman, D.W.; Rourke, K.F. Clinical outcomes of glansectomy with split-thickness skin graft reconstruction for localized penile cancer. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2019, 14, E482–E486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Che, K.; Wang, K.; Yuan, Y.; Li, F.; Li, Q. Circumferential full-thickness skin grafting: An excellent method for the treatment of short penile skin in adult men. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 999916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monn, M.F.; Socas, J.; Mellon, M.J. The Use of Full Thickness Skin Graft Phalloplasty During Adult Acquired Buried Penis Repair. Urology 2019, 129, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappas, A.; Katafigiotis, I.; Waterloos, M.; Spinoit, A.-F.; Ploumidis, A. Glans Resurfacing with Skin Graft for Penile Cancer: A Step-by-Step Video Presentation of the Technique and Review of the Literature. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 5219048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palminteri, E.; Fusco, F.; Berdondini, E.; Salonia, A. Aesthetic neo-glans reconstruction after penis-sparing surgery for benign. premalignant or malignant penile lesions. Arab J. Urol. 2011, 9, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palminteri, E.; Fusco, F.; Berdondini, E.; Saloni, A. Penis-Sparing Surgery with Neo-Glans Reconstruction for Benign, Premalignant or Malignant Penile Lesions. In Skin Grafts—Indications, Applications and Current Research; Spear, M., Ed.; InTech: Houston, TX, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, M.; Preto, M.; Oderda, M.; Timpano, M.; Russo, G.I.; Capogrosso, P.; Cocci, A.; Fode, M.; Gontero, P. Total Glans Resurfacing for the Management of Superficial Penile Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort Analysis in a Tertiary Referral Center. Urology 2020, 145, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Kelly, F.; Lonergan, P.; Lundon, D.; Nason, G.; Sweeney, P.; Cullen, I.; Hegarty, P. A Prospective Study of Total Glans Resurfacing for Localized Penile Cancer to Maximize Oncologic and Functional Outcomes in a Tertiary Referral Network. J. Urol. 2017, 197, 1258–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weibl, P.; Plank, C.; Hoelzel, R.; Hacker, S.; Remzi, M.; Huebner, W. Neo-glans reconstruction for penile cancer: Description of the primary technique using autologous testicular tunica vaginalis graft. Arab J. Urol. 2018, 16, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, K.; Cox, C.T.; Becker, B.C.; MacKay, B.J. Clinical applications of acellular dermal matrices: A review. Scars Burn. Health 2022, 8, 205951312110383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korkes, F.; Neves-Neto, O.C.; Wroclawski, M.L.; Tobias-Machado, M.; Pompeo, A.C.L.; Wroclawski, E.R. Parachute technique for partial penectomy. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2010, 36, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ranjan, S.; Ghorai, R.; Kumar, S.; Usha, P.; Panwar, V.; Kundal, A. Modified “parachute technique” of partial penectomy: A penile preservation surgery for carcinoma penis. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2021, 10, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberger, M.L.; Lowe, B.A. Penile Stump Advancement as An Alternative to Perineal Urethrostomy after Penile Amputation. J. Urol. 1999, 161, 893–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slongo, J.; de Vries, H.M.; Le, T.-L.; Korkes, F.; Albersen, M.; Zhu, Y.; Master, V.; Spiess, P.E. MP11-01 Largest Multi-Center International Experience With perineal Urethrostomy in The Management of Penile Cancer: Incidence and Management of Stenosis. J. Urol. 2020, 203, e135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, H.M.; Chipollini, J.; Slongo, J.; Boyd, F.; Korkes, F.; Albersen, M.; Roussel, E.; Zhu, Y.; Ye, D.-W.; Master, V.; et al. Outcomes of perineal urethrostomy for penile cancer: A 20-year international multicenter experience. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2021, 39, 500.e9–500.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcone, M.; Preto, M.; Ferro, I.; Cirigliano, L.; Peretti, F.; Plamadeala, N.; Scavone, M.; Lavagno, F.; Oderda, M.; Gontero, P. Surgical and Functional Outcomes of Penile Amputation and Perineal Urethrostomy Configuration in Invasive Penile Cancer. Urology 2023, 177, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.G.; Christopher, A.N.; Ralph, D.J. Phalloplasty following penectomy for penile cancer. Asian J. Urol. 2022, 9, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogoras, N. Uber die volle plastische wiederherstellung eines zum Koitus fahigen Penis (Peni plastica totalis). Zentralbl. Chir. 1936, 22, 1271–1276. [Google Scholar]

- Garaffa, G.; Raheem, A.A.; Christopher, N.A.; Ralph, D.J. Total phallic reconstruction after penile amputation for carcinoma. BJU Int. 2009, 104, 852–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orticochea, M. A New Method of Total Reconstruction of the Penis. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 1972, 25, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, E.E.; Friedlander, D.; Lue, K.; Anele, U.A.; Khurgin, J.L.; Bivalacqua, T.J.; Burnett, A.L.; Redett, R.J.; Gearhart, J.P. Sexual Function and Quality of Life Before and After Penile Prosthesis Implantation Following Radial Forearm Flap Phalloplasty. Urology 2017, 104, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year | Treatment Modality | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Hajiran et al., 2021 [12] | 5-FU | Complete response in 65%, partial response in 25%, and no response in 10% at 18-month median follow-up; median recurrence-free survival of 14 months. |

| Manjunath et al., 2017 [14] | 5-FU and Imiquimod | 10-year 50% complete response rate for 5-FU and 44% for Imiquimod; 31% partial response for 5-FU. |

| Torelli et al., 2017 [16] | Imiquimod then CO2 laser | Ten patients followed for mean of 26 months; no residual tumor in six, stable disease in two, and progressive disease in two. |

| Bandieramonte et al., 2008 [17] | CO2 laser | 10-year recurrence rate of 17.5% with amputation rate of 5.5%. |

| Meijer et al., 2007 [21] | Laser therapy | 44 patients followed for mean of 52.1 months; local recurrence in 48%, 20% recurrence elsewhere on the glans penis; nodal metastases in 10 patients, 8 of whom had T2 disease on biopsy. |

| Windahl et al., 2004 [22] | Combination CO2 and Nd:YAG laser | 67 men with median follow-up of 42 months; during follow-up, 59 alive and 8 had died of penile carcinoma (2) and concurrent disease (6). Of 13 patients (19%) with local recurrence, 10 underwent repeat laser treatment successfully. |

| Sosnowski et al., 2016 [27] | Wide local excision | pT1 and T2: local recurrence is relatively common, but five-year RFS is 63%. |

| Baumgarten et al., 2018 [28] | Glansectomy | 282 pT2 patients in cohort, 60.9% were treated with glansectomy; 85.7% of the pT2 patients recurred 5 years. |

| Sakalis et al., 2022 [30] | Glansectomy | Review of 1681 men (86.4% pT1-2); five-year RFS from 78.0–95.8%. |

| Alcala et al., 2022 [33] | Mohs surgery | 43 patients with Ta-T2 disease (including Tis); overall local recurrence rate was 2% (n = 1) at median 47 months; local recurrence in none with Ta-T1 disease at 5 years; local recurrence for T2 patients 14% at one year. |

| Veeratterapillay et al., 2015 [35] | Partial/radical penectomy | Median follow-up of 61 months; penile-preserving surgery (49%), partial penectomy (24%), radical penectomy (24%), and chemotherapy or radiotherapy for metastatic disease (3%); organ-preserving surgery: local recurrence rate 18% (4% for amputative surgery), with 94% of recurrences within three years; five-year CSS of 85% and a 10-year CSS of 81%. |

| Djajadiningrat et al., 2014 [36] | Local therapy/partial/radical penectomy | 859 patients (pT1-3) treated from 1956 to 2012; penile amputations decreased; 5-year local recurrence after penile preservation was 27% (3.8% after partial penectomy). Preservation no different compared to (partial) amputation; penile preservation group → local recurrence was not associated with CSS. |

| Author, Year | Treatment Modality | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Triana et al., 2017 [39] | Penile Skin Grafting | Both split- and full-thickness skin grafting are reasonable options for reconstruction after glansectomy, wide local excision, or Mohs surgery; higher graft failure rate in full-thickness grafts and graft must be 10–20% larger due to contracture. |

| Pappas et al., 2019; Palminteri et al., 2011; O’Kelly et al., 2017; Weibel et al., 2018 [45,46,49,50] | Glans Resurfacing and Creation of Neo-glans | Total glans resurfacing is a promising reconstructive option for localized, superficial penile cancer (CIS, Ta, and T1 grade 1/2); complication rate of <5% and graft-take rate of nearly 100%; neo-glans created with either split-thickness skin graft, acellular dermal matrix, or tunica vaginalis graft. |

| Korkes et al., 2010 [52] | Creation of Functional Penile Stump | Following amputation, use the “parachute” technique: ventral urethral spatulation and suturing the “V” skin flap from ventral to dorsal, so as to approximate the edges while preserving a urethral meatus; retention of the most penile function and universal approach. |

| Slongo et al., 2020 [55] | Perineal Urethrostomy | 246 patients had perineal urethrostomy: 65% were free of postoperative complications (wound infection (15%), dehiscence (5%) and tissue necrosis (2%)). A total of 35 out of 246 (14%) patients experienced perineal urethrostomy stenosis (PUS). |

| De Vries et al., 2021 [56] | Perineal Urethrostomy | 299 patients had perineal urethrostomy: 19% experienced complications, with wound infections and dehiscence being most prevalent; 12% experienced PUS, 74% of whom underwent revision. |

| Garaffa et al., 2009 [60] | Phalloplasty and Penile Implant | 15 patients received radial artery free flap total phallic reconstruction; 14 voided standing; all were cosmetically pleased; five of seven who received a prosthesis were able to participate in penetrative intercourse; common complications are urethral strictures and fistulae. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zekan, D.; Praetzel, R.; Luchey, A.; Hajiran, A. Local Therapy and Reconstruction in Penile Cancer: A Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 2704. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16152704

Zekan D, Praetzel R, Luchey A, Hajiran A. Local Therapy and Reconstruction in Penile Cancer: A Review. Cancers. 2024; 16(15):2704. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16152704

Chicago/Turabian StyleZekan, David, Rebecca Praetzel, Adam Luchey, and Ali Hajiran. 2024. "Local Therapy and Reconstruction in Penile Cancer: A Review" Cancers 16, no. 15: 2704. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16152704

APA StyleZekan, D., Praetzel, R., Luchey, A., & Hajiran, A. (2024). Local Therapy and Reconstruction in Penile Cancer: A Review. Cancers, 16(15), 2704. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16152704