Improving Quality of Life and Psychosocial Health for Penile Cancer Survivors: A Narrative Review

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

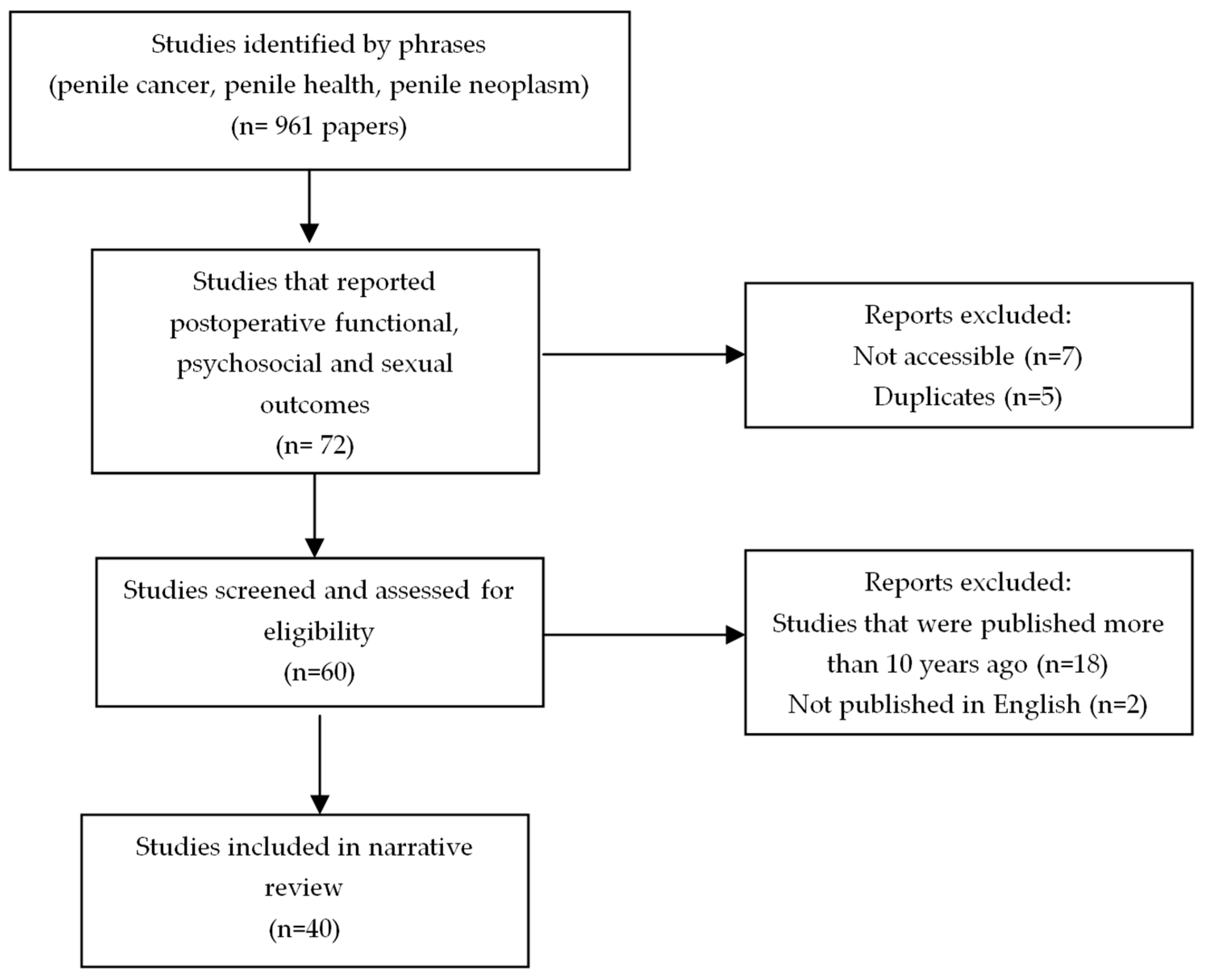

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Post-Treatment Quality of Life Assessment

3.2. Post-Treatment Psychosocial Assessment

3.3. Post-Treatment Urinary Outcomes

3.4. Post-Treatment Sexual Outcomes

3.5. Post-Treatment Support

4. Methodological Challenges and Strength

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hakenberg, O.W.; Drager, D.L.; Erbersdobler, A.; Naumann, C.M.; Junemann, K.P.; Protzel, C. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Penile Cancer. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2018, 115, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harju, E.; Pakarainen, T.; Vasarainen, H.; Törnävä, M.; Helminen, M.; Perttilä, I.; Kaipia, A. Health-Related Quality of Life, Self-esteem and Sexual Functioning among Patients Operated for Penile Cancer—A Cross-sectional Study. J. Sex. Med. 2021, 18, 1524–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, P.E.; Spiess, P.E.; Agarwal, N.; Biagioli, M.C.; Eisenberger, M.A.; Greenberg, R.E.; Herr, H.W.; Inman, B.A.; Kuban, D.A.; Kuzel, T.M.; et al. Penile cancer: Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2013, 11, 594–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahoud, J.; Kohli, M.; Spiess, P.E. Management of Advanced Penile Cancer. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2021, 96, 720–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paster, I.C.; Chipollini, J. Importance of Addressing the Psychosocial Impact of Penile Cancer on Patients and Their Families. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2022, 38, 151286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddineni, S.B.; Lau, M.M.; Sangar, V.K. Identifying the needs of penile cancer sufferers: A systematic review of the quality of life, psychosexual and psychosocial literature in penile cancer. BMC Urol. 2009, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynard, J.; Brewster, S.F.; Biers, S.; Neal, N.L.; Reynard, J.; Brewster, S.F.; Biers, S.; Neal, N.L. Urological neoplasia. In Oxford Handbook of Urology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Protzel, C.; Alcaraz, A.; Horenblas, S.; Pizzocaro, G.; Zlotta, A.; Hakenberg, O.W. Lymphadenectomy in the Surgical Management of Penile Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2009, 55, 1075–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orom, H.; Nelson, C.J.; Underwood, W., III; Homish, D.L.; Kapoor, D.A. Factors associated with emotional distress in newly diagnosed prostate cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology 2015, 24, 1416–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakalis, V.I.; Campi, R.; Barreto, L.; Garcia-Perdomo, H.A.; Greco, I.; Zapala, Ł.; Kailavasan, M.; Antunes-Lopes, T.; Marcus, J.D.; Manzie, K.; et al. What Is the Most Effective Management of the Primary Tumor in Men with Invasive Penile Cancer: A Systematic Review of the Available Treatment Options and Their Outcomes. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2022, 40, 58–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosnowski, R.; Wolski, J.K.; Kulpa, M.; Ziętalewicz, U.; Kosowicz, M.; Kalinowski, T.; Demkow, T. Assessment of quality of life in patients surgically treated for penile cancer: Impact of aggressiveness in surgery. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2017, 31, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, J.; Chavarriaga, J.; Ortiz, A.; Orrego, P.; Rueda, S.; Quiroga, W.; Fernandez, N.; Patiño, G.; Tobar, V.; Villareal, N.; et al. Oncological and Functional Outcomes after Organ-Sparing Plastic Reconstructive Surgery for Penile Cancer. Urology 2020, 142, 161–165.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audenet, F.; Sfakianos, J.P. Psychosocial impact of penile carcinoma. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2017, 6, 874–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draeger, D.L.; Sievert, K.D.; Hakenberg, O.W. Cross-Sectional Patient-Reported Outcome Measuring of Health-Related Quality of Life with Establishment of Cancer- and Treatment-Specific Functional and Symptom Scales in Patients with Penile Cancer. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2018, 16, e1215–e1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, W.G.; Klaassen, Z.; Jen, R.P.; Hughes, W.M.t.; Neal, D.E., Jr.; Terris, M.K. Analysis of Suicide Risk in Patients with Penile Cancer and Review of the Literature. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2018, 16, e257–e261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaassen, Z.; Jen, R.P.; DiBianco, J.M.; Reinstatler, L.; Li, Q.; Madi, R.; Lewis, R.W.; Smith, A.M.; Neal, D.E., Jr.; Moses, K.A.; et al. Factors associated with suicide in patients with genitourinary malignancies. Cancer 2015, 121, 1864–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, J.K.; Sørensen, C.M.; Krarup, K.P.; Jensen, J.B. Quality of life, voiding and sexual function of penile cancer patients: DaPeCa-10-a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. BJUI Compass 2022, 3, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preto, M.; Falcone, M.; Blecher, G.; Capece, M.; Cocci, A.; Timpano, M.; Gontero, P. Functional and Patient Reported Outcomes Following Total Glans Resurfacing. J. Sex. Med. 2021, 18, 1099–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beech, B.B.; Chapman, D.W.; Rourke, K.F. Clinical outcomes of glansectomy with split-thickness skin graft reconstruction for localized penile cancer. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2020, 14, E482–E486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavarriaga, J.; Becerra, L.; Camacho, D.; Godoy, F.; Forero, J.; Cabrera, M.; López-de-Mesa, B.; Ramirez, A.; Suso-Palau, D.; Varela, R. Inverted urethral flap reconstruction after partial penectomy: Long-term oncological and functional outcomes. Urol. Oncol. 2022, 40, 169.e13–169.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcone, M.; Preto, M.; Ferro, I.; Cirigliano, L.; Peretti, F.; Plamadeala, N.; Scavone, M.; Lavagno, F.; Oderda, M.; Gontero, P. Surgical and Functional Outcomes of Penile Amputation and Perineal Urethrostomy Configuration in Invasive Penile Cancer. Urology 2023, 177, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witty, K.; Branney, P.; Evans, J.; Bullen, K.; White, A.; Eardley, I. The impact of surgical treatment for penile cancer—Patients’ perspectives. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2013, 17, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törnävä, M.; Harju, E.; Vasarainen, H.; Pakarainen, T.; Perttilä, I.; Kaipia, A. Men’s experiences of the impact of penile cancer surgery on their lives: A qualitative study. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2022, 31, e13548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, R.C.; Riley, A.; Wagner, G.; Osterloh, I.H.; Kirkpatrick, J.; Mishra, A. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): A multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology 1997, 49, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skeppner, E.; Fugl-Meyer, K. Dyadic Aspects of Sexual Well-Being in Men with Laser-Treated Penile Carcinoma. Sex. Med. 2015, 3, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Suarez-Ibarrola, R.; Cortes-Telles, A.; Miernik, A. Health-Related Quality of Life and Sexual Function in Patients Treated for Penile Cancer. Urol. Int. 2018, 101, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, F.R.; Romero, K.R.; Mattos, M.A.; Garcia, C.R.; Fernandes Rde, C.; Perez, M.D. Sexual function after partial penectomy for penile cancer. Urology 2005, 66, 1292–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilio, S.; Tufano, A.; Pezone, G.; Alvino, P.; Spena, G.; Pandolfo, S.D.; Del Prete, P.; Amato, C.; Damiano, R.; Salonia, A.; et al. Sexual Outcomes after Conservative Management for Patients with Localized Penile Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 10501–10508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, E.; Sutcliffe, A.; Keegan, P.; Clifford, T.; Matu, J.; Shannon, O.M.; Griffiths, A. Effects of partial penectomy for penile cancer on sexual function: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, C.; Primeau, C.; Bowker, M.; Jensen, B.; MacLennan, S.; Yuan, Y.; N’Dow, J. What are the unmet supportive care needs of men affected by penile cancer? A systematic review of the empirical evidence. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 48, 101805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windahl, T.; Skeppner, E.; Andersson, S.O.; Fugl-Meyer, K.S. Sexual function and satisfaction in men after laser treatment for penile carcinoma. J. Urol. 2004, 172, 648–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, S.L.; Wang, C.F.; Yao, X.D.; Dai, B.; Ye, D.W. Organ-sparing surgery for penile cancer: Complications and outcomes. Urology 2011, 78, 1121–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alei, G.; Letizia, P.; Sorvillo, V.; Alei, L.; Ricottilli, F.; Scuderi, N. Lichen sclerosus in patients with squamous cell carcinoma. Our experience with partial penectomy and reconstruction with ventral fenestrated flap. Ann. Ital. Chir. 2012, 83, 363–367. [Google Scholar]

- Delaunay, B.; Soh, P.N.; Delannes, M.; Riou, O.; Malavaud, B.; Moreno, F.; Craven, J.; Soulie, M.; Huyghe, E. Brachytherapy for penile cancer: Efficacy and impact on sexual function. Brachytherapy 2014, 13, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kieffer, J.M.; Djajadiningrat, R.S.; Muilekom, E.A.M.v.; Graafland, N.M.; Horenblas, S.; Aaronson, N.K. Quality of Life for Patients Treated for Penile Cancer. J. Urol. 2014, 192, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soh, P.N.; Delaunay, B.; Nasr, E.B.; Delannes, M.; Soulie, M.; Huyghe, E. Evaluation of sexual functions and sexual behaviors after penile brachytherapy in men treated for penile carcinoma. Basic Clin. Androl. 2014, 24, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, X.; Zheng, D.; Liu, C.; Xu, H.; Xie, M.; Zhou, J.; Yao, H.J.; Wang, Z. A Comparative study of two types of organ-sparing surgeries for early stage penile cancer: Wide local excision vs partial penectomy. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 44, 1425–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornes, R.; Earle, W. Current Unmet Needs in Penile Cancer: The Way Forward? Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2022, 38, 151282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year | Intervention, Number of Patients | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Sosnowski et al., 2017 [12] | total penectomy (n = 11) partial penectomy (n = 27) penile-sparing surgery (n = 13) | 59% maintained relationships with their partners post-operatively. No significant effect of surgery type on relations with female partners. |

| Perez et al., 2020 [13] | glans resurfacing (n = 20) partial penectomy (n = 23) glansectomy (n = 14) | Mean health status of 82.5%; 94% did not consider themselves to be experiencing anxiety or depression. |

| Draeger et al., 2018 [15] | organ-sparing surgery (n = 73) total penectomy (n = 3) | Mean rate of self-reported global QoL score was 54.0 (SD 5.9), which corresponds to an average QoL (score 0–100) and is significantly below the age-standardized average for German patients. |

| Jakobsen et al., 2022 [18] | local resection (n = 53) partial penectomy (n = 34) total penectomy (n = 19) | When compared to the control group, penile cancer survivors reported higher levels of anxiety. A significantly lower proportion of penile cancer survivors reported the importance of sexuality as moderate or great. |

| Witty et al., 2013 [23] | All underwent surgical intervention ranging from circumcision to penectomy (n = 29) | Patients reported avoiding urinals, pools, and saunas. Others reported suicidal ideations due to loss of masculinity. |

| Tornava et al., 2022 [24] | partial or total penectomy (n = 11) glansectomy (n = 11) circumcision or wide excision (n = 7) | Suicidal ideation due to effects of cancer and surgery on their lives. Shift in patients’ priorities, emphasizing more time with loved ones. Men denied need for post-treatment support outside of their family. |

| Author, Year | Number of Patients | Functional Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Perez et al., 2020 [13] | 57 | Median voiding score of 4 (IQR 1–15), median IIEF of 19 (IQR 10.75–25). |

| Li et al., 2017 [33] | 32 | One patient had mild-to-moderate ED and 21 had the same ratings of sexual function as before. All reported satisfactory urination. |

| Alei et al., 2012 [34] | 10 | Average IIEF scores were 21.6, 13, and 19.7 in the preoperative period, 13, and 40 months, respectively. |

| Draeger et al., 2018 [15] | 76 | Patients reported significant limitations in sexual function and body image, as well as adverse effects resulting from therapy. |

| Jakobsen et al., 2022 [18] | 157 | Significant decrease in use of pads and nocturia at 2 years or more. However, less frequency of orgasm and intercourse compared to control group. |

| Preto et al., 2021 [19] | 37 | No significant changes in IIEF scores. |

| Beech et al., 2020 [20] | 12 | Most patients who had preserved ED preoperatively maintained it post-operatively. Most reported successful voiding while standing; others reported spraying. |

| Chavarriaga et al., 2022 [21] | 51 | Mean voiding score of the ICIQ-MLUTS was 1.7 ± 3.2. Mean IIEF score of 17.3 ± 7. |

| Falcone et al., 2023 [22] | 10 | Median preoperative IPSS was 15 (IQR 12–19); post-operative IPSS was 6 (IQR 5–7). |

| Skeppner et al., 2015 [26] | 29 | Most common sexual dysfunction was dyspareunia. The IIEF score was registered as “normal” with a score ≥ 22. |

| Cilio et al., 2023 [29] | 25 | Diabetic patients and those who underwent WLE exhibited higher susceptibility to having erectile dysfunction. |

| Witty et al., 2013 [23] | 27 | Some patients reported decreased libido, while also avoiding sexual intercourse with partners following treatment. |

| Delaunay et al., 2014 [35] a | 19 | 10 (58.8%) patients remained sexually active after treatment, 7 (36.8%) patients had no erectile dysfunction, 8 (42.1%) had frequent erections, 15 (78.9%) maintained nocturnal erections, and 10 (58.8%) rated their erections as “hard” or “almost hard”. |

| Kieffer et al., 2014 [36] | 90 | IIEF scores were better for penile-sparing surgery on orgasmic function scale versus partial penectomy. |

| Soh et al., 2014 [37] a | 19 | Sexual inactivity increased from 10.5% to 47.3%, erectile dysfunction increased from 21.1% to 57.8%, and 42% had an absence of ejaculation or orgasm. |

| Wan et al., 2018 [38] | 15 | IIEF post-operative scores of patients who underwent WLE were better than their preoperative scores. |

| Tornava et al., 2022 [24] | 31 | Reports of impaired physical endurance and limitations due to post-operative pelvic pain. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Torres Irizarry, V.M.; Paster, I.C.; Ogbuji, V.; Gomez, D.M.; Mccormick, K.; Chipollini, J. Improving Quality of Life and Psychosocial Health for Penile Cancer Survivors: A Narrative Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 1309. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16071309

Torres Irizarry VM, Paster IC, Ogbuji V, Gomez DM, Mccormick K, Chipollini J. Improving Quality of Life and Psychosocial Health for Penile Cancer Survivors: A Narrative Review. Cancers. 2024; 16(7):1309. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16071309

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorres Irizarry, Von Marie, Irasema Concepcion Paster, Vanessa Ogbuji, D’Andre Marquez Gomez, Kyle Mccormick, and Juan Chipollini. 2024. "Improving Quality of Life and Psychosocial Health for Penile Cancer Survivors: A Narrative Review" Cancers 16, no. 7: 1309. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16071309

APA StyleTorres Irizarry, V. M., Paster, I. C., Ogbuji, V., Gomez, D. M., Mccormick, K., & Chipollini, J. (2024). Improving Quality of Life and Psychosocial Health for Penile Cancer Survivors: A Narrative Review. Cancers, 16(7), 1309. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16071309