Functional and Disability Outcomes in NSCLC Patients Post-Lobectomy Undergoing Pulmonary Rehabilitation: A Biopsychosocial Approach

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Instruments and Measures

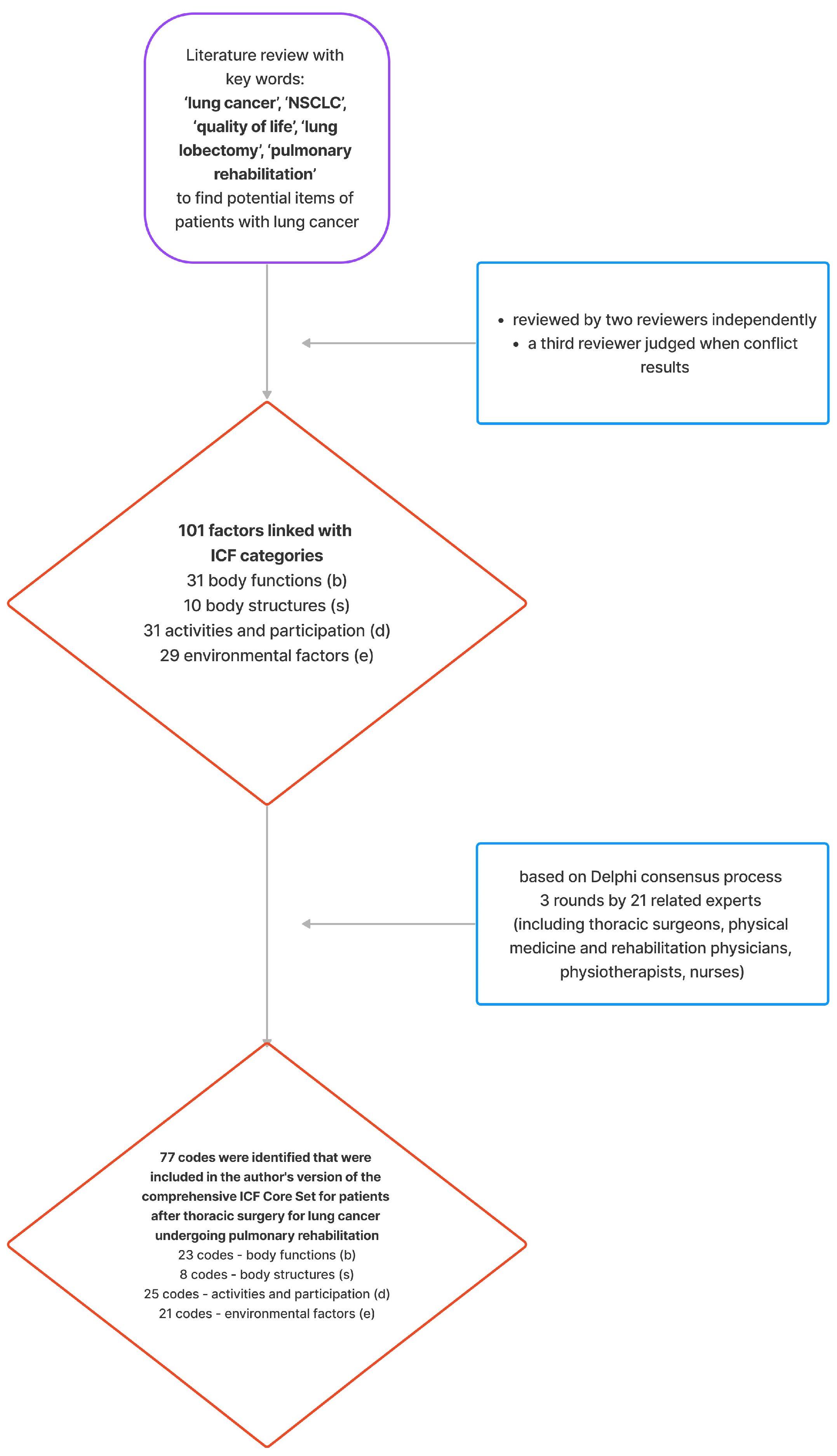

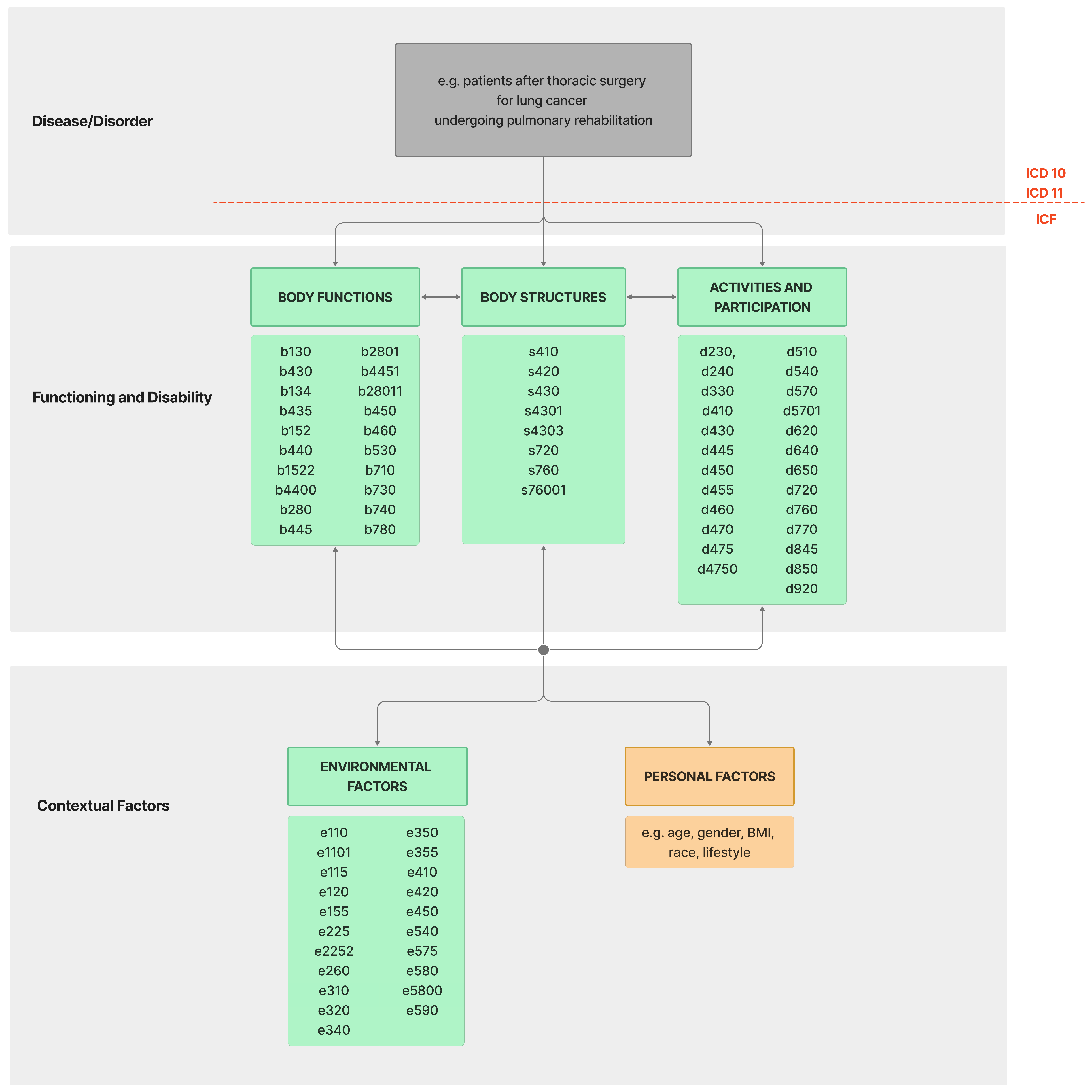

2.3.1. Development of a Literature Review and Selection of ICF Categories

2.3.2. Consensus Procedure

2.3.3. A Comprehensive ICF Core Set Specifically Designed to Capture the Functional Impairments and Limitations of Lung Cancer Patients

2.3.4. The World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0)

- Domain 1: Cognition (D1)—understanding and communicating;

- Domain 2: Mobility (D2)—moving and getting around;

- Domain 3: Self-care (D3)—e.g., hygiene, dressing, and eating;

- Domain 4: Getting along (D4)—assesses interactions with other people and difficulties that may arise in this area of life due to health status;

- Domain 5: Life activities (D5)—household and work/school activities;

2.3.5. Rehabilitation Procedure Scheme

2.3.6. Data Analysis

2.3.7. Statistical Environment

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Sample

3.2. Characteristics of Sociodemographic Parameters, Clinical Data, and Major Risk Factors of the Studied Sample

3.3. Assessment of Inter-Rater Agreement among Experts on Individual ICF Codes Using the Delphi Consensus Method

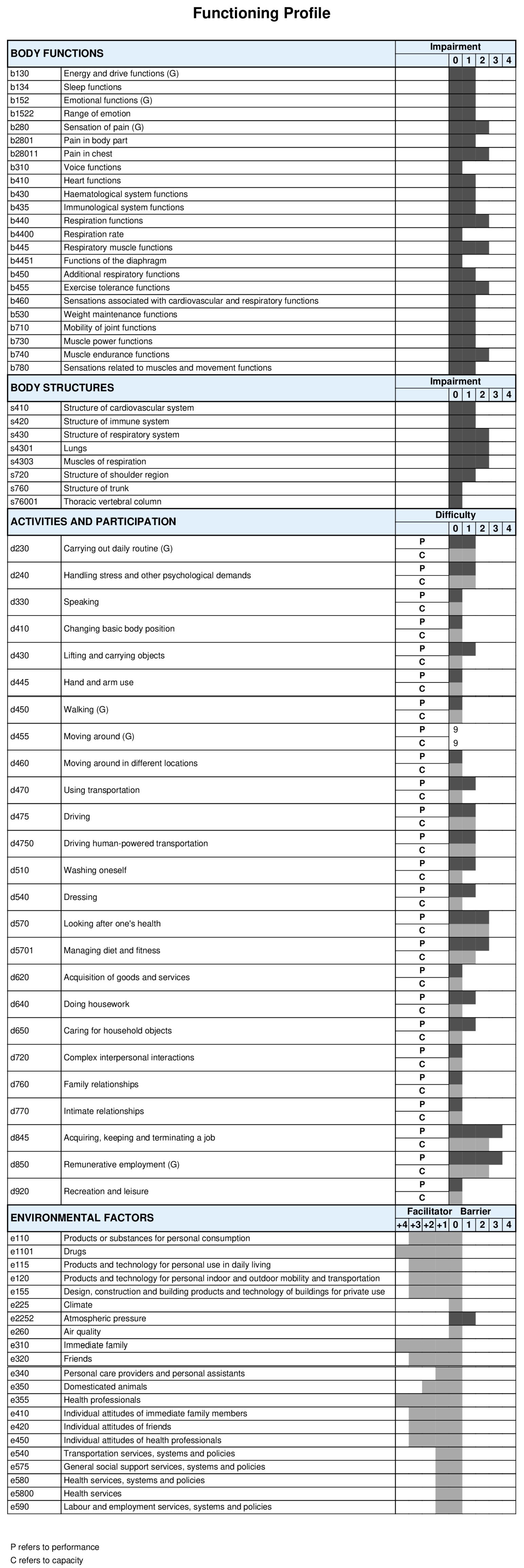

3.4. Characteristics of the Results for Individual Codes of the Comprehensive ICF Core Set for Lung Cancer

3.4.1. Domain—Body Functions

3.4.2. Domain—Body Structures

3.4.3. Domain—Activities and Participation Qualifiers, Performance, and Capacity

3.4.4. Domain—Environmental Factors

3.5. Average Results for Individual Codes of the Comprehensive ICF Core Set for Lung Cancer

3.6. Characteristics of the Results of Individual Categories of the WHODAS 2.0 Questionnaire

3.7. Analysis of the Association between the Selected ICF Core Set Parameters and WHODAS 2.0

3.7.1. Domain 2: Mobility

3.7.2. Domain 3: Self-Care

3.7.3. Domain 4: Getting along with People

3.7.4. Domains 5(1) and 5(2): Household Activities and Work or School Activities

3.7.5. Domain 6: Participation

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of the Comprehensive ICF Core Set Results for Lung Cancer Patients

4.2. Analysis of Emotional and Psychological Function Codes

4.3. Pain Sensation Codes in Post-Surgical Lung Cancer Patients

4.4. Voice Function Codes Post-Lung Resection Surgery

4.5. Hematological and Immunological Function Codes Post-Surgery

4.6. Respiratory Function Codes Pre- and Post-Lung Resection Surgery

4.7. Nutrition and Metabolism Function Codes Post-Surgery

4.8. Muscle Function and Mobility Codes Post-Surgery

4.9. Activity and Participation Domain According to the ICF

4.10. Environmental Factors Domain According to the ICF

WHODAS 2.0 Data Analysis

4.11. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zappa, C.; Mousa, S.A. Non-small cell lung cancer: Current treatment and future advances. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2016, 5, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blandin Knight, S.; Crosbie, P.A.; Balata, H.; Chudziak, J.; Hussell, T.; Dive, C. Progress and prospects of early detection in lung cancer. Open Biol. 2017, 7, 170070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schabath, M.B.; Cote, M.L. Cancer Progress and Priorities: Lung Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2019, 28, 1563–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberg, A.J.; Samet, J.M. Epidemiology of lung cancer. Chest 2003, 123, 21S–49S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Groot, P.M.; Wu, C.C.; Carter, B.W.; Munden, R.F. The epidemiology of lung cancer. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2018, 7, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samet, J.M.; Avila-Tang, E.; Boffetta, P.; Hannan, L.M.; Olivo-Marston, S.; Thun, M.J.; Rudin, C.M. Lung cancer in never smokers: Clinical epidemiology and environmental risk factors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 5626–5645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiro, S.G.; Porter, J.C. Lung cancer—Where are we today? Current advances in staging and nonsurgical treatment. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 166, 1166–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesbitt, J.C.; Putnam, J.B., Jr.; Walsh, G.L.; Roth, J.A.; Mountain, C.F. Survival in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1995, 60, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettinger, D.S.; Wood, D.E.; Aggarwal, C.; Aisner, D.L.; Akerley, W.; Bauman, J.R.; Bharat, A.; Bruno, D.S.; Chang, J.Y.; Chirieac, L.R.; et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 1.2020. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2019, 17, 1464–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackey, A.; Donington, J.S. Surgical management of lung cancer. Semin. Interv. Radiol. 2013, 30, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Scordilli, M.; Michelotti, A.; Bertoli, E.; De Carlo, E.; Del Conte, A.; Bearz, A. Targeted Therapy and Immunotherapy in Early-Stage Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Current Evidence and Ongoing Trials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Available online: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Federici, S.; Bracalenti, M.; Meloni, F.; Luciano, J.V. World Health Organization disability assessment schedule 2.0: An international systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 39, 2347–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Üstün, T.B.; Kostanjsek, N.; Chatterji, S.; Rehm, J. Measuring Health and Disability: Manual for WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Win, T.; Sharples, L.; Wells, F.C.; Ritchie, A.J.; Munday, H.; Laroche, C.M. Effect of lung cancer surgery on quality of life. Thorax 2005, 60, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Février, E.; Yip, R.; Becker, B.J.; Taioli, E.; Yankelevitz, D.F.; Flores, R.; Henschke, C.I.; Schwartz, R.M.; IELCART Investigators. Change in quality of life of stage IA lung cancer patients after sublobar resection and lobectomy. J. Thorac. Dis. 2020, 12, 3488–3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, Z. Use of Delphi in health sciences research: A narrative review. Medicine 2023, 102, e32829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Makowski, D.; Lüdecke, D.; Patil, I.; Thériault, R.; Ben-Shachar, M.; Wiernik, B. Automated Results Reporting as a Practical Tool to Improve Reproducibility and Methodological Best Practices Adoption. CRAN. 2023. Available online: https://easystats.github.io/report/ (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Sjoberg, D.; Whiting, K.; Curry, M.; Lavery, J.; Larmarange, J. Reproducible Summary Tables with the gtsummary Package. R. J. 2021, 13, 570–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; Bryan, J. readxl: Read Excel Files. R package version 1.4.3. 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=readxl (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Wickham, H.; François, R.; Henry, L.; Müller, K.; Vaughan, D. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. R Package Version 1.1.2. 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Revelle, W. psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research, R Package Version 2.3.9; Northwestern University: Evanston, IL, USA, 2023; Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Cardiovascular_and_Respiratory_Conditions. ICF Research Branch. Available online: https://www.icf-research-branch.org/icf-core-sets/category/12-cardiovascularandrespiratoryconditions (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Uchitomi, Y.; Mikami, I.; Kugaya, A.; Akizuki, N.; Nagai, K.; Nishiwaki, Y.; Akechi, T.; Okamura, H. Depression after successful treatment for nonsmall cell lung carcinoma. Cancer 2000, 89, 1172–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linares-Moya, M.; Rodríguez-Torres, J.; Heredia-Ciuró, A.; Granados-Santiago, M.; López-López, L.; Quero-Valenzuela, F.; Valenza, M.C. Psychological distress prior to surgery is related to symptom burden and health status in lung cancer survivors. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 1579–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadzka-Fabijan, A.; Fabijan, A.; Łochowski, M.; Pryt, Ł.; Pieszyński, I.; Kujawa, J.E.; Polis, B.; Nowosławska, E.; Zakrzewski, K.; Kozak, J. Assessment of the Functioning Profile of Patients with Lung Cancer Undergoing Lobectomy in Relation to the ICF Rehabilitation Core Set. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajiyama, S.; Miyoshi, H.; Kato, T.; Kawamoto, M. Evaluation of postoperative pain intensity related to post-thoracotomy pain syndrome occurring after video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy for lung cancer. Masui. Jpn. J. Anesthesiol. 2014, 63, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sano, Y.; Shigematsu, H.; Okazaki, M.; Sakao, N.; Mori, Y.; Yukumi, S.; Izutani, H. Hoarseness after radical surgery with systematic lymph node dissection for primary lung cancer. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2019, 55, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Song, D.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L. Effects of lung resection on heart structure and function: A tissue Doppler ultrasound survey of 43 cases. Biomed. Rep. 2023, 20, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, Q.; Ma, L.; Mei, J.D.; Zhu, Y.K.; Che, G.W.; Lin, Y.D.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Kou, Y.L.; Yang, J.J.; et al. Immune function of patients following lobectomy for lung cancers: A comparative study between video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery and posterolateral thoracotomy. J. Sichuan Univ. Med. Sci. Ed. 2013, 44, 126–129. [Google Scholar]

- Onodera, K.; Ueda, K.; Hasumi, T. P67.02 Long-term Follow-up Data of Respiratory Function in Patients with Lung Cancer Undergoing Surgery. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021, 16, S1197–S1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, K.; Izumi, N.; Tsukioka, T.; Chung, K.; Komatsu, H.; Toda, M.; Miyamoto, H.; Kimura, T.; Suzuki, S.; Yoshida, A.; et al. P3.16-032 Prediction of Postoperative Lung Function in Patients with Lung Cancer by Lung Lobe. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2017, 12, S2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakada, T.; Tsukamoto, Y.; Kato, D.; Shibazaki, T.; Yabe, M.; Hirano, J.; Ohtsuka, T. Analysis of postoperative weight loss associated with prognosis after lobectomy for lung cancer. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2022, 62, ezac479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, C.; Ureña, A.; Macia, I.; Rivas, F.; Déniz, C.; Muñoz, A.; Serratosa, I.; Poltorak, V.; Moya-Guerola, M.; Masuet-Aumatell, C.; et al. The Influence of Preoperative Nutritional and Systemic Inflammatory Status on Perioperative Outcomes following Da Vinci Robot-Assisted Thoracic Lung Cancer Surgery. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, I.; Allan, L.; Hug, A.; Westran, N.; Heinemann, C.; Hewish, M.; Mehta, A.; Saxby, H.; Ezhil, V. Nutritional status and symptom burden in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: Results of the dietetic assessment and intervention in lung cancer (DAIL) trial. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2023, 13, e213–e219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtin, C.; Franssen, F.M.E.; Vanfleteren, L.E.G.W.; Groenen, M.T.J.; Wouters, E.F.M.; Spruit, M.A. Lower-limb muscle function is a determinant of exercise tolerance after lung resection surgery in patients with lung cancer. Respirology 2017, 22, 1185–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, C.L.; Connolly, B.; Denehy, L.; Hart, N.; Antippa, P.; Lin, K.Y.; Parry, S.M. Understanding factors influencing physical activity and exercise in lung cancer: A systematic review. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 983–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalheri, V.; Granger, C.L. Exercise training as part of lung cancer therapy. Respirology 2020, 25, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg Nes, L.; Liu, H.; Patten, C.A.; Rausch, S.M.; Sloan, J.A.; Garces, Y.I.; Cheville, A.L.; Yang, P.; Clark, M.M. Physical activity level and quality of life in long term lung cancer survivors. Lung Cancer 2012, 77, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Q.; Qi, S.; Yue, Y.; Shen, J.; Zhang, B.; Sun, W.; Qian, W.; Islam, M.S.; Saha, S.C.; Wu, J. Structural and functional alterations of the tracheobronchial tree after left upper pulmonary lobectomy for lung cancer. Biomed. Eng. Online 2019, 18, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paone, G.; Rose, G.; Giudice, G.; Cappelli, S. Physiology of pleural space after pulmonary resection. J. Xiangya Med. 2018, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, Y.; Utsushikawa, Y.; Deguchi, H.; Tomoyasu, M.; Kudo, S.; Shigeeda, W.; Yoshimura, R.; Kanno, H.; Saito, H. Correlation with spontaneous pneumothorax and weather change, especially warm front approaching. J. Thorac. Dis. 2021, 13, 1584–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, K.; Li, Y.; Jia, X.; Liu, C. Multiple Impacts of Urban Built and Natural Environment on Lung Cancer Incidence: A Case Study in Bengbu. J. Healthc. Eng. 2023, 2023, 4876404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Qualifier | Impairment Level | The Scale of the Problem | |

|---|---|---|---|

| xxx.0 | NO impairment | (none, absent, negligible, …) | 0–4% |

| xxx.1 | MILD impairment | (slight, low, …) | 5–24% |

| xxx.2 | MODERATE impairment | (medium, fair, …) | 25–49% |

| xxx.3 | SEVERE impairment | (high, extreme, …) | 50–95% |

| xxx.4 | COMPLETE impairment | (total, …) | 96–100% |

| xxx.8 | not specified | ||

| xxx.9 | not applicable | ||

| Qualifier | Impairment Level | The Scale of the Problem | |

|---|---|---|---|

| xxx.0 | NO impairment | (none, absent, negligible, …) | 0–4% |

| xxx.1 | MILD impairment | (slight, low, …) | 5–24% |

| xxx.2 | MODERATE impairment | (medium, fair, …) | 25–49% |

| xxx.3 | SEVERE impairment | (high, extreme, …) | 50–95% |

| xxx.4 | COMPLETE impairment | (total, …) | 96–100% |

| xxx.8 | not specified | ||

| xxx.9 | not applicable | ||

| Second Qualifier | Nature |

|---|---|

| xxx.x0 | no change in structure |

| xxx.x1 | total absence |

| xxx.x2 | partial absence |

| xxx.x3 | additional part |

| xxx.x4 | aberrant dimensions |

| xxx.x5 | discontinuity |

| xxx.x6 | deviating position |

| xxx.x7 | qualitative changes in structure, including accumulation of fluid |

| not specified | |

| xxx.x8 | not applicable |

| xxx.x9 | |

| Third Qualifier | Localization |

| xxx.x0 | more than one region |

| xxx.x1 | right |

| xxx.x2 | left |

| xxx.x3 | both sides |

| xxx.x4 | front |

| xxx.x5 | back |

| xxx.x6 | proximal |

| xxx.x7 | distal |

| xxx.x8 | not specified |

| xxx.x9 | not applicable |

| Qualifier | Difficulty Level | The Scale of the Problem | |

|---|---|---|---|

| xxx.0 | NO difficulty | (none, absent, negligible, …) | 0–4% |

| xxx.1 | MILD difficulty | (slight, low, …) | 5–24% |

| xxx.2 | MODERATE difficulty | (medium, fair, …) | 25–49% |

| xxx.3 | SEVERE difficulty | (high, extreme, …) | 50–95% |

| xxx.4 | COMPLETE difficulty | (total, …) | 96–100% |

| xxx.8 | not specified | ||

| xxx.9 | not applicable | ||

| Qualifier | Barrier/Facilitator | The Scale of the Problem | |

|---|---|---|---|

| xxx.0 | NO barrier | (none, absent, negligible, …) | 0–4% |

| xxx.1 | MILD barrier | (slight, low, …) | 5–24% |

| xxx.2 | MODERATE barrier | (medium, fair, …) | 25–49% |

| xxx.3 | SEVERE barrier | (high, extreme, …) | 50–95% |

| xxx.4 | COMPLETE barrier | (total, …) | 96–100% |

| xxx.+0 | NO facilitator | (none, absent, negligible, …) | 0–4% |

| xxx.+1 | MILD facilitator | (slight, low, …) | 5–24% |

| xxx.+2 | MODERATE facilitator | (medium, fair, …) | 25–49% |

| xxx.+3 | SUBSTANTIAL facilitator | (high, extreme, …) | 50–95% |

| xxx.+4 | COMPLETE facilitator | (total, …) | 96–100% |

| xxx.8 | not specified | ||

| xxx.9 | not applicable | ||

| None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Extreme or Cannot Do |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Characteristic | N | Overall a | Sex | p c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n1 = 23 a | Male, n2 = 27 a | ||||

| Age [years] | 50 | 63.00 (57.25, 68.50) | 60.00 (56.50, 65.00) | 65.00 (61.00, 70.00) | 0.070 |

| Smoking | 50 | 34.00 (68.00%) b | 13.00 (56.52%) b | 21.00 (77.78%) b | 0.108 d |

| BMI [kg/m2] | 50 | 24.60 (22.81, 28.01) | 24.80 (21.94, 27.58) | 24.28 (22.89, 27.59) | 1.000 d |

| Location of the lesions | 50 | 0.047 d | |||

| Left lung | 25.00 (50.00%) b | 8.00 (34.78%) b | 17.00 (62.96%) b | ||

| Right lung | 25.00 (50.00%) b | 15.00 (65.22%) b | 10.00 (37.04%) b | ||

| Lung re-expansion time [days] | 50 | 5.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 4.00 (4.00, 5.00) | 5.00 (4.00, 6.00) | 0.265 |

| Past cancer episode | 50 | 17.00 (34.00%) b | 10.00 (43.48%) b | 7.00 (25.93%) b | 0.192 d |

| ICF Code | ICF Body Functions Category Title | Inter-Rater Agreement M ± SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd | 3rd/4rd | Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 | |

| b110 | Consciousness functions | 0.40 ± 0.50 | 0.24 ± 0.44 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b114 | Orientation functions | 0.24 ± 0.44 | 0.12 ± 0.33 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b130 | Energy and drive functions | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b134 | Sleep functions | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b152 | Emotional functions | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b1522 | Range of emotion | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b280 | Sensation of pain | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b2801 | Pain in body part | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b28011 | Pain in chest | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b310 | Voice functions | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b410 | Heart functions | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b415 | Blood vessel functions | 0.56 ± 0.51 | 0.36 ± 0.49 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b420 | Blood pressure functions | 0.48 ± 0.51 | 0.16 ± 0.37 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b430 | Hematological system functions | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b435 | Immunological system functions | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b440 | Respiration functions | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b4400 | Respiration rate | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b445 | Respiratory muscle functions | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b4451 | Functions of the diaphragm | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b450 | Additional respiratory functions | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b455 | Exercise tolerance functions | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b460 | Sensations associated with cardiovascular and respiratory functions | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b510 | Ingestion functions | 0.36 ± 0.49 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b530 | Weight maintenance functions | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b545 | Water, mineral, and electrolyte balance functions | 0.56 ± 0.51 | 0.28 ± 0.46 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b610 | Urinary excretory functions | 0.56 ± 0.51 | 0.20 ± 0.41 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b710 | Mobility of joint functions | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b730 | Muscle power functions | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b740 | Muscle endurance functions | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b780 | Sensations related to muscles and movement functions | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| b820 | Repair functions of the skin | 0.12 ± 0.33 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| ICF Code | ICF Body Structures Category Title | Inter-Rater Agreement M ± SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd | 3rd/4rd | Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 | |

| s410 | Structure of the cardiovascular system | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| s420 | Structure of the immune system | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| s430 | Structure of the respiratory system | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| s4301 | Lungs | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| s4303 | Muscles of respiration | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| s710 | Structure of the head and neck region | 0.12 ± 0.33 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| s720 | Structure of the shoulder region | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| s760 | Structure of the trunk | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| s76001 | Thoracic vertebral column | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| s810 | Structure of areas of skin | 0.24 ± 0.44 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| ICF Code | ICF Activities and Participation Category Title | Inter-Rater Agreement M ± SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd | 3rd/4rd | Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 | |

| d230 | Carrying out daily routine | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d240 | Handling stress and other psychological demands | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d330 | Speaking | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d410 | Changing basic body position | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d415 | Maintaining a body position | 0.52 ± 0.51 | 0.24 ± 0.44 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d420 | Transferring oneself | 0.36 ± 0.49 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d430 | Lifting and carrying objects | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d445 | Hand and arm use | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d450 | Walking | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d455 | Moving around | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d460 | Moving around in different locations | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d465 | Moving around using equipment | 0.52 ± 0.51 | 0.16 ± 0.37 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d470 | Using transportation | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d475 | Driving | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d4750 | Driving human-powered transportation | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d510 | Washing oneself | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d520 | Caring for body parts | 0.68 ± 0.48 | 0.32 ± 0.48 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d540 | Dressing | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d570 | Looking after one’s health | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d5701 | Managing diet and fitness | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d620 | Acquisition of goods and services | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d640 | Doing housework | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d650 | Caring for household objects | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d660 | Assisting others | 0.64 ± 0.49 | 0.24 ± 0.44 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d720 | Complex interpersonal interactions | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d760 | Family relationships | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d770 | Intimate relationships | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d845 | Acquiring, keeping, and terminating a job | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d850 | Remunerative employment | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d910 | Community life | 0.48 ± 0.51 | 0.12 ± 0.33 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| d920 | Recreation and leisure | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| ICF Code | ICF Environmental Factors Category Title | Inter-Rater Agreement M ± SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd | 3rd/4rd | Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 | |

| e110 | Products or substances for personal consumption | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e1101 | Drugs | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e115 | Products and technology for personal use in daily living | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e120 | Products and technology for personal indoor and outdoor mobility and transportation | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e150 | Design, construction, and building products and technology of buildings for public use | 0.28 ± 0.46 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e155 | Design, construction, and building products and technology of buildings for private use | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e225 | Climate | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e2252 | Atmospheric pressure | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e245 | Time-related changes | 0.44 ± 0.51 | 0.20 ± 0.41 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e2450 | Day/night cycles | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e250 | Sound | 0.16 ± 0.37 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e260 | Air quality | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e310 | Immediate family | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e320 | Friends | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e340 | Personal care providers and personal assistants | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e350 | Domesticated animals | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e355 | Health professionals | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e410 | Individual attitudes of immediate family members | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e420 | Individual attitudes of friends | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e450 | Individual attitudes of health professionals | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e460 | Societal attitudes | 0.36 ± 0.49 | 0.16 ± 0.37 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e540 | Transportation services, systems, and policies | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e555 | Associations and organizational services, systems, and policies | 0.36 ± 0.49 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e570 | Social security services, systems, and policies | 0.44 ± 0.51 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e575 | General social support services, systems, and policies | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e580 | Health services, systems, and policies | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e5800 | Health services | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e585 | Education and training services, systems, and policies | 0.20 ± 0.41 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| e590 | Labor and employment services, systems, and policies | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | |

| Characteristic | N | Sex | p c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female n1 = 23 a | Male n2 = 27 a | |||

| Domain 1: Cognition | ||||

| D1.1: Concentrating on doing something for ten minutes? | 50 | 0.878 | ||

| none | 6.00 (26.09%) | 7.00 (25.93%) | ||

| mild | 15.00 (65.22%) | 15.00 (55.56%) | ||

| moderate | 2.00 (8.70%) | 4.00 (14.81%) | ||

| severe | 0.00 (0.00%) | 1.00 (3.70%) | ||

| D1.2: Remembering to do important things? | 50 | 1.000 | ||

| none | 6.00 (26.09%) | 6.00 (22.22%) | ||

| mild | 15.00 (65.22%) | 18.00 (66.67%) | ||

| moderate | 2.00 (8.70%) | 3.00 (11.11%) | ||

| D1.3: Analyzing and finding solutions to problems in day-to-day life? | 50 | 0.475 | ||

| none | 17.00 (73.91%) | 16.00 (59.26%) | ||

| mild | 6.00 (26.09%) | 9.00 (33.33%) | ||

| moderate | 0.00 (0.00%) | 2.00 (7.41%) | ||

| D1.4: Learning a new task, for example, learning how to get to a new place? | 50 | 0.695 | ||

| none | 5.00 (21.74%) | 5.00 (18.52%) | ||

| mild | 16.00 (69.57%) | 16.00 (59.26%) | ||

| moderate | 2.00 (8.70%) | 5.00 (18.52%) | ||

| severe | 0.00 (0.00%) | 1.00 (3.70%) | ||

| D1.5: Generally understanding what people say? | 50 | 0.614 | ||

| none | 22.00 (95.65%) | 24.00 (88.89%) | ||

| mild | 1.00 (4.35%) | 3.00 (11.11%) | ||

| D1.6: Starting and maintaining a conversation? | 50 | |||

| none | 23.00 (100.00%) | 27.00 (100.00%) | ||

| Domain 2: Mobility | ||||

| D2.1: Standing for long periods, such as 30 min? | 50 | 0.449 | ||

| none | 12.00 (52.17%) | 9.00 (33.33%) | ||

| mild | 6.00 (26.09%) | 11.00 (40.74%) | ||

| moderate | 5.00 (21.74%) | 6.00 (22.22%) | ||

| severe | 0.00 (0.00%) | 1.00 (3.70%) | ||

| D2.2: Standing up from sitting down? | 50 | 1.000 | ||

| none | 19.00 (82.61%) | 22.00 (81.48%) | ||

| mild | 4.00 (17.39%) | 4.00 (14.81%) | ||

| moderate | 0.00 (0.00%) | 1.00 (3.70%) | ||

| D2.3: Moving around inside your home? | 50 | 0.493 | ||

| none | 23.00 (100.00%) | 25.00 (92.59%) | ||

| mild | 0.00 (0.00%) | 2.00 (7.41%) | ||

| D2.4: Getting out of your home? | 50 | 0.240 | ||

| none | 23.00 (100.00%) | 23.00 (85.19%) | ||

| mild | 0.00 (0.00%) | 3.00 (11.11%) | ||

| moderate | 0.00 (0.00%) | 1.00 (3.70%) | ||

| D2.5: Walking a long distance, such as a kilometer [or equivalent]? | 50 | 0.958 | ||

| none | 5.00 (21.74%) | 4.00 (14.81%) | ||

| mild | 13.00 (56.52%) | 16.00 (59.26%) | ||

| moderate | 5.00 (21.74%) | 6.00 (22.22%) | ||

| severe | 0.00 (0.00%) | 1.00 (3.70%) | ||

| Domain 3: Self-care | ||||

| D3.1: Washing your whole body? | 50 | 0.783 | ||

| none | 13.00 (56.52%) | 12.00 (44.44%) | ||

| mild | 7.00 (30.43%) | 11.00 (40.74%) | ||

| moderate | 3.00 (13.04%) | 3.00 (11.11%) | ||

| severe | 0.00 (0.00%) | 1.00 (3.70%) | ||

| D3.2: Getting dressed? | 50 | 0.948 | ||

| none | 15.00 (65.22%) | 15.00 (55.56%) | ||

| mild | 7.00 (30.43%) | 9.00 (33.33%) | ||

| moderate | 1.00 (4.35%) | 2.00 (7.41%) | ||

| severe | 0.00 (0.00%) | 1.00 (3.70%) | ||

| D3.3: Eating? | 50 | 0.632 | ||

| none | 14.00 (60.87%) | 13.00 (48.15%) | ||

| mild | 8.00 (34.78%) | 11.00 (40.74%) | ||

| moderate | 1.00 (4.35%) | 3.00 (11.11%) | ||

| D3.4: Staying by yourself for a few days? | 50 | 0.494 | ||

| none | 14.00 (60.87%) | 13.00 (48.15%) | ||

| mild | 9.00 (39.13%) | 12.00 (44.44%) | ||

| moderate | 0.00 (0.00%) | 2.00 (7.41%) | ||

| Domain 4: Getting along with people | ||||

| D4.1: Dealing with people you do not know? | 50 | 1.000 | ||

| none | 3.00 (13.04%) | 4.00 (14.81%) | ||

| mild | 19.00 (82.61%) | 22.00 (81.48%) | ||

| moderate | 1.00 (4.35%) | 1.00 (3.70%) | ||

| D4.2: Maintaining a friendship? | 50 | 0.643 d | ||

| none | 13.00 (56.52%) | 17.00 (62.96%) | ||

| mild | 10.00 (43.48%) | 10.00 (37.04%) | ||

| D4.3: Getting along with people who are close to you? | 50 | 1.000 | ||

| none | 21.00 (91.30%) | 25.00 (92.59%) | ||

| mild | 2.00 (8.70%) | 2.00 (7.41%) | ||

| D4.4: Making new friends? | 50 | 0.031 | ||

| none | 2.00 (8.70%) | 10.00 (37.04%) | ||

| mild | 20.00 (86.96%) | 17.00 (62.96%) | ||

| moderate | 1.00 (4.35%) | 0.00 (0.00%) | ||

| D4.5: Sexual activities? | 50 | 0.885 | ||

| none | 12.00 (52.17%) | 12.00 (44.44%) | ||

| mild | 10.00 (43.48%) | 14.00 (51.85%) | ||

| moderate | 1.00 (4.35%) | 1.00 (3.70%) | ||

| Domain 5: Life activities | ||||

| D5.1: Taking care of your household responsibilities? | 50 | 0.345 | ||

| none | 15.00 (65.22%) | 13.00 (48.15%) | ||

| mild | 8.00 (34.78%) | 12.00 (44.44%) | ||

| moderate | 0.00 (0.00%) | 2.00 (7.41%) | ||

| D5.2: Doing your most important household tasks well? | 50 | 0.278 | ||

| none | 16.00 (69.57%) | 13.00 (48.15%) | ||

| mild | 6.00 (26.09%) | 11.00 (40.74%) | ||

| moderate | 1.00 (4.35%) | 3.00 (11.11%) | ||

| D5.3: Getting all the household work done that you needed to do? | 50 | 0.658 | ||

| none | 9.00 (39.13%) | 7.00 (25.93%) | ||

| mild | 12.00 (52.17%) | 16.00 (59.26%) | ||

| moderate | 2.00 (8.70%) | 4.00 (14.81%) | ||

| D5.4: Getting your household work done as quickly as needed? | 50 | 0.173 | ||

| none | 5.00 (21.74%) | 1.00 (3.70%) | ||

| mild | 15.00 (65.22%) | 22.00 (81.48%) | ||

| moderate | 3.00 (13.04%) | 4.00 (14.81%) | ||

| D5.01: In the past 30 days, how many days did you reduce or completely miss household work because of your health condition? | 50 | 10.00 (5.00, 20.00) b | 10.00 (10.00, 25.00) b | 0.119 e |

| D5.5: Your day-to-day work/school? | 50 | 0.898 | ||

| none | 10.00 (43.48%) | 12.00 (44.44%) | ||

| mild | 9.00 (39.13%) | 8.00 (29.63%) | ||

| moderate | 4.00 (17.39%) | 6.00 (22.22%) | ||

| severe | 0.00 (0.00%) | 1.00 (3.70%) | ||

| D5.6: Doing your most important work/school tasks well? | 50 | 0.923 | ||

| none | 10.00 (43.48%) | 12.00 (44.44%) | ||

| mild | 9.00 (39.13%) | 11.00 (40.74%) | ||

| moderate | 4.00 (17.39%) | 3.00 (11.11%) | ||

| severe | 0.00 (0.00%) | 1.00 (3.70%) | ||

| D5.7: Getting all the work done that you need to do? | 50 | 0.712 | ||

| none | 10.00 (43.48%) | 12.00 (44.44%) | ||

| mild | 5.00 (21.74%) | 3.00 (11.11%) | ||

| moderate | 8.00 (34.78%) | 11.00 (40.74%) | ||

| severe | 0.00 (0.00%) | 1.00 (3.70%) | ||

| D5.8: Getting your work done as quickly as needed? | 50 | 0.482 | ||

| none | 10.00 (43.48%) | 12.00 (44.44%) | ||

| mild | 0.00 (0.00%) | 1.00 (3.70%) | ||

| moderate | 12.00 (52.17%) | 10.00 (37.04%) | ||

| severe | 1.00 (4.35%) | 4.00 (14.81%) | ||

| D5.9: Have you had to work at a lower level because of a health condition? | 50 | 0.945 d | ||

| not applicable (0) | 10.00 (43.48%) | 12.00 (44.44%) | ||

| Yes (2) No (1) | 13.00 (56.52%) 0.00 (0.00%) | 15.00 (55.56%) 0.00 (0.00%) | ||

| D5.10: Did you earn less money as a result of a health condition? | 50 | 1.000 | ||

| not applicable (0) | 10.00 (43.48%) | 12.00 (44.44%) | ||

| No (1) | 1.00 (4.35%) | 2.00 (7.41%) | ||

| Yes (2) | 12.00 (52.17%) | 13.00 (48.15%) | ||

| D5.02: In the past 30 days, how many days did you miss work for half a day or more because of your health condition? | 50 | 10.00 (0.00, 10.00) b | 10.00 (0.00, 10.00) b | 0.967 e |

| Domain 6: Participation | ||||

| D6.1: How much of a problem did you have joining community activities (for example, festivities, religious or other activities) in the same way as anyone else can? | 50 | 0.387 | ||

| none | 13.00 (56.52%) | 16.00 (59.26%) | ||

| mild | 8.00 (34.78%) | 11.00 (40.74%) | ||

| moderate | 2.00 (8.70%) | 0.00 (0.00%) | ||

| D6.2: How much of a problem did you have because of barriers or hindrances in the world around you? | 50 | 0.641 | ||

| none | 5.00 (21.74%) | 3.00 (11.11%) | ||

| mild | 14.00 (60.87%) | 19.00 (70.37%) | ||

| moderate | 4.00 (17.39%) | 5.00 (18.52%) | ||

| D6.3: How much of a problem did you have living with dignity because of the attitudes and actions of others? | 50 | 0.115 | ||

| none | 10.00 (43.48%) | 10.00 (37.04%) | ||

| mild | 10.00 (43.48%) | 17.00 (62.96%) | ||

| moderate | 3.00 (13.04%) | 0.00 (0.00%) | ||

| D6.4: How much time did you spend on your health condition or its consequences? | 50 | 0.047 d | ||

| moderate | 15.00 (65.22%) | 10.00 (37.04%) | ||

| severe | 8.00 (34.78%) | 17.00 (62.96%) | ||

| D6.5: How much have you been emotionally affected by your health condition? | 50 | 0.231 | ||

| moderate | 13.00 (56.52%) | 10.00 (37.04%) | ||

| severe | 10.00 (43.48%) | 15.00 (55.56%) | ||

| extreme | 0.00 (0.00%) | 2.00 (7.41%) | ||

| D6.6: How much has your health been a drain on the financial resources of you or your family? | 50 | 0.387 | ||

| mild | 1.00 (4.35%) | 0.00 (0.00%) | ||

| moderate | 15.00 (65.22%) | 15.00 (55.56%) | ||

| severe | 7.00 (30.43%) | 12.00 (44.44%) | ||

| D6.7: How much of a problem did your family have because of your health problems? | 50 | 0.065 | ||

| moderate | 16.00 (69.57%) | 11.00 (40.74%) | ||

| severe | 7.00 (30.43%) | 15.00 (55.56%) | ||

| extreme | 0.00 (0.00%) | 1.00 (3.70%) | ||

| D6.8: How much of a problem did you have in doing things by yourself for relaxation or pleasure? | 50 | 0.153 | ||

| none | 12.00 (52.17%) | 9.00 (33.33%) | ||

| mild | 10.00 (43.48%) | 18.00 (66.67%) | ||

| moderate | 1.00 (4.35%) | 0.00 (0.00%) | ||

| WHO DAS 2.0 | ICF Code | Performance | Capacity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rho | p | rho | p | ||

| Domain 2: Mobility | |||||

| D2.2 | d410 | 0.38 | 0.007 | 0.24 | 0.097 |

| D2.3 | d460 | 0.32 | 0.020 | 0.47 | 0.001 |

| D2.4 | d460 | 0.15 | 0.295 | 0.33 | 0.019 |

| D2.5 | d450 | 0.19 | 0.193 | 0.18 | 0.203 |

| Domain 3: Self-care | |||||

| D3.1 | d510 | 0.15 | 0.294 | 0.33 | 0.021 |

| D3.2 | d540 | 0.35 | 0.013 | 0.28 | 0.050 |

| D3.4 | d510 | 0.10 | 0.478 | 0.23 | 0.110 |

| D3.4 | d540 | 0.24 | 0.098 | 0.23 | 0.102 |

| D3.4 | d570 | −0.18 | 0.215 | −0.11 | 0.446 |

| D3.4 | d5701 | −0.16 | 0.277 | −0.21 | 0.145 |

| D3.4 | d620 | 0.03 | 0.861 | 0.08 | 0.547 |

| D3.4 | d640 | 0.03 | 0.854 | −0.08 | 0.577 |

| D3.4 | d650 | 0.10 | 0.489 | −0.13 | 0.370 |

| Domain 4: Getting along with people | |||||

| D4.1 | d720 1 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| D4.2 | d720 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| D4.3 | d760 2 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| D4.3 | d770 | −0.17 | 0.229 | −0.14 | 0.340 |

| D4.4 | d720 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| D4.5 | d770 | 0.03 | 0.852 | 0.12 | 0.400 |

| Domain 5(1): Household activities | |||||

| D5.1 | d640 | 0.27 | 0.062 | 0.01 | 0.927 |

| D5.1 | d650 | 0.18 | 0.220 | 0.13 | 0.396 |

| D5.2 | d640 | 0.25 | 0.075 | 0.02 | 0.917 |

| D5.2 | d650 | 0.14 | 0.343 | 0.13 | 0.376 |

| D5.3 | d640 | 0.23 | 0.100 | 0.02 | 0.900 |

| D5.3 | d650 | 0.08 | 0.575 | 0.07 | 0.614 |

| D5.4 | d640 | 0.26 | 0.066 | −0.03 | 0.819 |

| D5.4 | d650 | 0.15 | 0.311 | 0.08 | 0.571 |

| Domain 5(2): Work or school activities | |||||

| D5.5 | d845 | −0.82 | <0.001 | −0.78 | <0.001 |

| D5.5 | d850 | −0.77 | <0.001 | −0.77 | <0.001 |

| D5.6 | d845 | −0.77 | <0.001 | −0.76 | <0.001 |

| D5.6 | d850 | −0.76 | <0.001 | −0.78 | <0.001 |

| D5.7 | d845 | −0.82 | <0.001 | −0.81 | <0.001 |

| D5.7 | d850 | −0.81 | <0.001 | −0.83 | <0.001 |

| D5.8 | d845 | −0.85 | <0.001 | −0.84 | <0.001 |

| D5.8 | d850 | −0.82 | <0.001 | −0.84 | <0.001 |

| Domain 6: Participation | |||||

| D6.5 | b152 | 0.16 | 0.244 | - | - |

| D6.8 | d920 | 0.08 | 0.605 | 0.12 | 0.425 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zawadzka-Fabijan, A.; Fabijan, A.; Łochowski, M.; Pryt, Ł.; Polis, B.; Zakrzewski, K.; Kujawa, J.E.; Kozak, J. Functional and Disability Outcomes in NSCLC Patients Post-Lobectomy Undergoing Pulmonary Rehabilitation: A Biopsychosocial Approach. Cancers 2024, 16, 2281. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16122281

Zawadzka-Fabijan A, Fabijan A, Łochowski M, Pryt Ł, Polis B, Zakrzewski K, Kujawa JE, Kozak J. Functional and Disability Outcomes in NSCLC Patients Post-Lobectomy Undergoing Pulmonary Rehabilitation: A Biopsychosocial Approach. Cancers. 2024; 16(12):2281. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16122281

Chicago/Turabian StyleZawadzka-Fabijan, Agnieszka, Artur Fabijan, Mariusz Łochowski, Łukasz Pryt, Bartosz Polis, Krzysztof Zakrzewski, Jolanta Ewa Kujawa, and Józef Kozak. 2024. "Functional and Disability Outcomes in NSCLC Patients Post-Lobectomy Undergoing Pulmonary Rehabilitation: A Biopsychosocial Approach" Cancers 16, no. 12: 2281. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16122281

APA StyleZawadzka-Fabijan, A., Fabijan, A., Łochowski, M., Pryt, Ł., Polis, B., Zakrzewski, K., Kujawa, J. E., & Kozak, J. (2024). Functional and Disability Outcomes in NSCLC Patients Post-Lobectomy Undergoing Pulmonary Rehabilitation: A Biopsychosocial Approach. Cancers, 16(12), 2281. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16122281