Therapeutic Parent–Child Communication and Health Outcomes in the Childhood Cancer Context: A Scoping Review

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

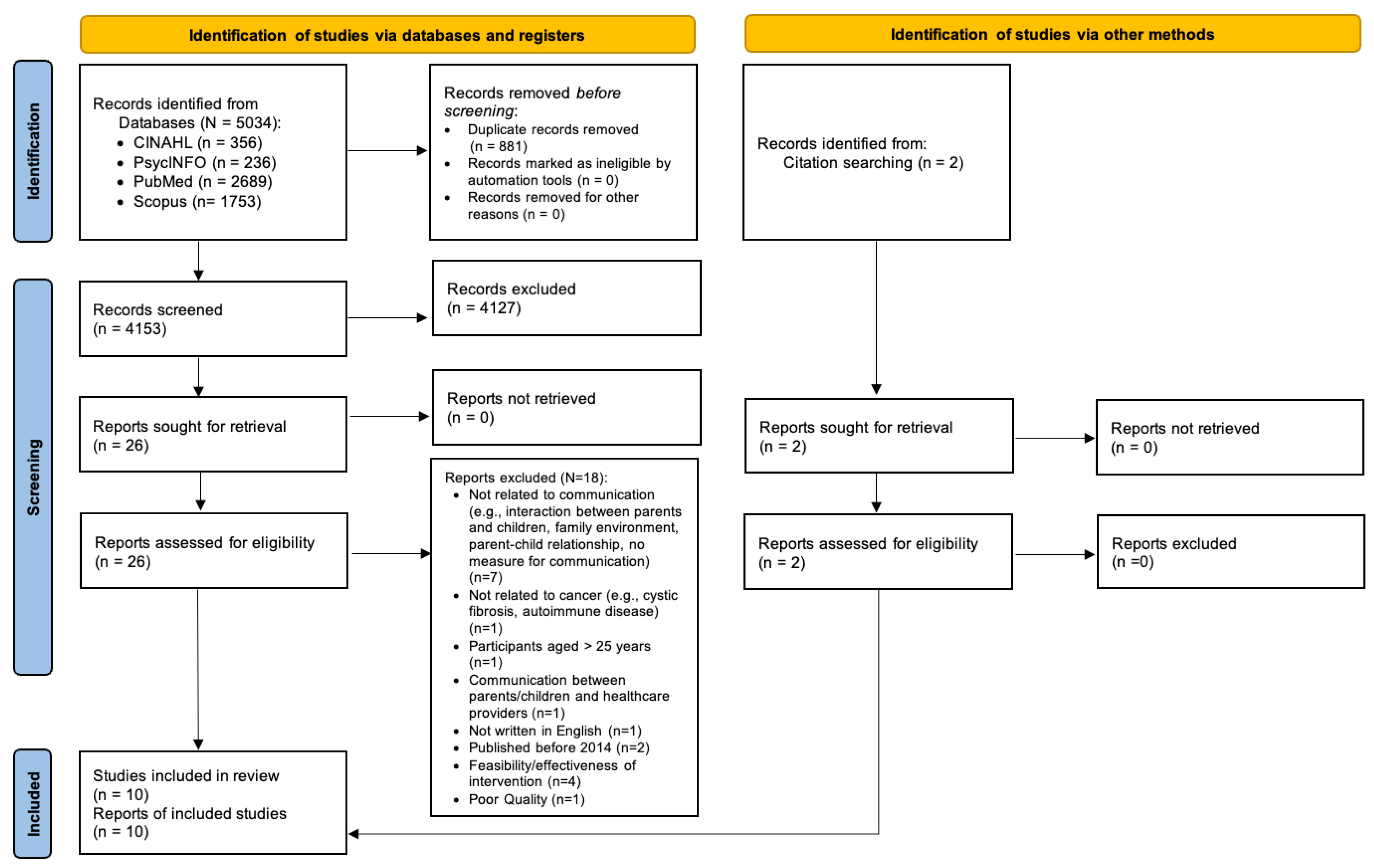

2.1. Literature Search and Screening

2.2. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Included Studies

3.2. The Characteristics of Children and Adolescents with Cancer

| Study/ Country | Objective | Design | Sample and Age Range (Groups) | Independent Variable (Measurement and Method) | Dependent Variable (Measurement and Method) | Relationship/ Characteristics of PAC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greeff et al. [38]/ Belgium | Identify resilience factors associated with family adaptation | Cross-sectional, correlational | 26 parents and 25 children aged 12–24 (G3 and 4) | Parents’ and children’s self-report of family communication (affirming/incendiary communication) (FPSC) | Parents’ and children’s self-report of family adaptation (FACI8) |

|

| Phillips-Salimi et al. [33]. USA | Identify the relationships among adolescents’ and parents’ perceptions on communication, family adaptability, and cohesion | Cross-sectional, correlational | 70 dyads: AYA aged 11–19 (G3&4) | Adolescents’ and parents’ self-reports on perceptions of (a) open family communication, and (b) problems in family communication (PACS) | Identify the relationships among adolescents’ and parents’ perceptions on communication, family adaptability, and cohesion (FACES-II) | Controlling for age and sex of AYA and parents,

|

| Murphy et al. [8]/ USA | Examine potential risk factors for adolescent PTSS at T1 (2 months after diagnosis), T2 (3 months after T2), and T3 (12-month follow-up) | Longitudinal, nonexperimental | 41 dyads: Adolescents aged 5–17 (G2, 3, and 4) | Observed maternal communication: macro level at T1 (IFIRS): harsh communication and withdrawn communication; observed maternal communication: micro level at T2 (IFIRS): solicit and validation | Adolescents’ and maternal self-report of the PTSS (the Impact of Events Scale–Revised) at T1 and T3 |

|

| Bai et al. [36]/ USA | Examine the associations between parent interaction behaviors, parent distress, child distress, and child cooperation during cancer-related port access placement across timepoints (T1–T4) | Longitudinal, nonexperimental | 43 dyads: Children aged 3–12 (G2 and 3) | Observation of parent caring verbal/nonverbal interactions: caring parent verbal interaction (P-CaReSS) and nonverbal behaviors (duration) | Observations of (a) child distress, (b) parent/child distress, and (c) child cooperation: (1) verbal/nonverbal child distress (the Karmanos Child Coping and Distress scale), (2) Parent/child distress (the Wong–Baker Faces Scale), (3) Child cooperation (CCS) | Children’s low verbal/nonverbal distress found following parents’ caring behaviors (eye contact, comforting, supporting/allowing, less availability, verbal protecting, avoiding assumption, believing in/esteem), except for verbal forms of care (e.g., criticizing, apologizing) (Yule’s Q ranged from −0.85 to −0.99) |

| Keim et al. [26]/ USA | Examine the relationships between PAC and adjustment at T1 (enrolment) and T2 (one year later) | Longitudinal, nonexperimental | 55 children with advanced cancer; 70 with nonadvanced disease; 60 without cancer as the control group and their mothers: adolescents aged 10–17 (G3 and 4) | Children’s self-reports on communication with their mother and father, separately (PACS) | Mothers’ self-reports on (a) child adjustment, (b) anxious/depressed scores, and (c) withdrawn/depressed scores (the Child Behavior Checklist) | The relationship between parent–child communication at T1 and child adjustment at T2:

|

| Viola et al. [35]/ USA | Examine associations among problem-solving skills, PAC, parent–adolescent dyadic functioning, and distress | Cross-sectional, correlational | 39 dyads: Adolescents aged 14–20 (G4) | Parents’ and adolescents’ self-reports of parent-adolescent cancer-related communication (CRCP) | Adolescents’ self-report of the level of adolescent distress (BSI) | No significant relationship between adolescent-reported cancer related communication problems and adolescents’ distress |

| Tillery et al. [34]/ USA | Identify the relationships between PAC and psychosocial outcomes | Cross-sectional, correlational | 165 dyads: adolescents aged 10–19 (G3 and 4) | Parents’ self-report of the parent–child relationship quality (PRQ): involvement, attachment, communication (quality of information exchange), parenting confidence, relational frustration | Children’s self-report of psychosocial outcomes: (1) post-traumatic stress symptoms (22-item UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-IV), (2) internalizing difficulties (BASC-2), (3) social functioning (self-regulation, empathy, responsibility, and social competence (SEARS) | Adolescents of caregivers who reported struggling relationship patterns (below average levels of parent–child relationship functioning across several domains) were more likely to report (1) increased level of PTSS (χ2 = 35.06), (2) elevated levels of internalizing symptoms (χ2 = 10.62), and (3) poorer social functioning (χ2 = 16.38) compared to youth of caregivers who reported normative or above average levels of relationship function |

| Al Ghriwati et al. [32]/ USA | Identify subtypes of family relationships and the effects of relationships on child adjustment upon treatment completion within 7 months | Secondary analysis, longitudinal data | 81 dyads: Children aged 6–14 (G3 and 4) | Children’s self-report of (1) closeness (e.g., how frequently you share information about things that you want others to know) and (2) discord (e.g., how frequently you disagree and quarrel with others) (NRI-RQV) | Caregivers’ self-report of children’s status: (1) internalizing and externalizing symptoms (CBCL), (2) peer relationships (PROMIS), (3) family functioning (FAD-GFS), (4) quality of life (the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0) |

|

| Barrios et al. [39]/ Spain | Explore (1) the openness about cancer, (2) the relationships between the types of communication and children’s emotion | Cross-sectional, mixed method | 52 dyads: children aged 6–14 (G3 and 4) | Self-report of open communication: the degree of information given to the child as categorized by (1) direct honest information, (2) nuanced or distorted information, and (3) no information at all | Self-report of child’s emotion (e.g., fear, anger, sadness, happiness, pain, boredom, loneliness, shame) and mother’s subjective emotion (e.g., fear, anger, sadness, frustration, anxiety, guilt) during the qualitative interviews |

|

| Park et al. [37]/ Republic of Korea | Identify risk and protective factors for family resilience that affect the adaptation of families of children with cancer | Cross-sectional, correlational | 111 dyads: children’s mean age of 8.3 (N/A) | Parents’ self-report of family communication (the Family Problem-Solving Communication Scale) | Parents’ self-report of family resilience (adaptation) (APGAR questionnaire) | Family communication skills found to be predictive of family adaptation (β = 0.40) |

3.3. The Characteristics of Parents of Children or Adolescents with Cancer

3.4. Parent–Child Communication in the Childhood Cancer Context

3.4.1. Types of Communication Being Measured

3.4.2. Types of Communication Being Measured

3.5. The Influence of Age and Developmental Stage

3.6. The Relationship between Parent–Child Communication and Physical Health Outcomes

3.7. The Relationship between Parent–Child Communication and Psychological Health Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Cancer Institute Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: An Overview. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/types/childhood-cancers/ccss (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Suh, E.; Stratton, K.L.; Leisenring, W.M.; Nathan, P.C.; Ford, J.S.; Freyer, D.R.; McNeer, J.L.; Stock, W.; Stovall, M.; Krull, K.R.; et al. Late Mortality and Chronic Health Conditions in Long-term Survivors of Early-adolescent and Young Adult Cancers: A Retrospective Cohort Analysis from The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, S.S.; Saha, T.; Ojha, A.; Das, A.; Daruvala, R.; Reghu, K.S.; Achari, R. What Do You need to Learn in Paediatric Psycho-Oncology? Ecancermedicalscience 2019, 13, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Ghriwati, N.; Stevens, E.; Velázquez-Martin, B.; Hocking, M.C.; Schwartz, L.A.; Barakat, L.P. Family Factors and Health-related Quality of Life within 6 Months of Completion of Childhood Cancer Treatment. Psychooncology 2021, 30, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Morris, P.A. The Ecology of Developmental Processes. In Handbook of Child Psychology: Theoretical Models of Human Development, Volume 1; John Wiley & Sons Inc: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 993–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Juth, V. The Social Ecology of Adolescents’ Cancer Experience: A Narrative Review and Future Directions. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2016, 1, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Schoors, M.; Caes, L.; Knoble, N.B.; Goubert, L.; Verhofstadt, L.L.; Alderfer, M.A. Systematic Review: Associations Between Family Functioning and Child Adjustment After Pediatric Cancer Diagnosis: A Meta-Analysis. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2016, 42, jsw070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, L.K.; Rodriguez, E.M.; Schwartz, L.; Bemis, H.; Desjardins, L.; Gerhardt, C.A.; Vannatta, K.; Saylor, M.; Compas, B.E. Longitudinal Associations among Maternal Communication and Adolescent Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms after Cancer Diagnosis. Psychooncology 2016, 25, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eche, I.J.; Aronowitz, T.; Shi, L.; McCabe, M.A. Parental Uncertainty: Parents’ Perceptions of Health-Related Quality of Life in Newly Diagnosed Children with Cancer. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2019, 23, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laursen, B.; Collins, W.A. Parent—Child Communication During Adolescence. In The Routledge Handbook of Family Communication; Vangelisti, A.L., Vangelisti, A.L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 357–372. [Google Scholar]

- Haase, J.E.; Kintner, E.K.; Monahan, P.O.; Robb, S.L. The Resilience in Illness Model, Part 1. Cancer Nurs. 2014, 37, E1–E12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compas, B.E.; Jaser, S.S.; Bettis, A.H.; Watson, K.H.; Gruhn, M.A.; Dunbar, J.P.; Williams, E.; Thigpen, J.C. Coping, Emotion Regulation, and Psychopathology in Childhood and Adolescence: A Meta-Analysis and Narrative review. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 939–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña, M.A.; Kataoka, S. Family Communication Styles and Resilience among Adolescents. Soc. Work 2017, 62, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, E.E.; LeBlanc Farris, K. Interpersonal Communication and Coping with Cancer: A Multidisciplinary Theoretical Review of the Literature. Commun. Theory 2019, 29, 236–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, Q. Couple-Based Communication Interventions for Cancer Patient–Spousal Caregiver Dyads’ Psychosocial Adaptation to Cancer: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldsmith, D.J.; Domann-Scholz, K. The Meanings of ‘Open Communication’ among Couples Coping with a Cardiac Event. J Commun. 2013, 63, 266–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.Y.; Steger, M.F.; Shin, D.W.; Kim, S.Y.; Yang, H.-K.; Cho, J.; Jeong, A.; Park, K.; Kweon, S.S.; Park, J.-H. Patient-Family Communication Mediates the Relation between Family Hardiness and Caregiver Positivity: Exploring the Moderating Role of Caregiver Depression and Anxiety. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2019, 37, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittenberg-Lyles, E.; Goldsmith, J.; Oliver, D.P.; Demiris, G.; Rankin, A. Targeting Communication Interventions to Decrease Caregiver Burden. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2012, 28, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.L.; Wolf, B.M.; Fowler, C.; Canzona, M.R. Experiences of “Openness” between Mothers and Daughters during Breast Cancer: Implications for Coping and Healthy Outcomes. Psychooncology 2017, 26, 1872–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh-Burke, K. Family Communication and Coping with Cancer. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 1992, 10, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotcher, J.M. The Effects of Family Communication on Psychosocial Adjustment of Cancer Patients. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 1993, 21, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrodt, P. Family Strength and Satisfaction as Functions of Family Communication Environments. Commun. Q. 2009, 57, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommariva, S.; Vázquez-Otero, C.; Medina-Ramirez, P.; Aguado Loi, C.; Fross, M.; Dias, E.; Martinez Tyson, D. Hispanic Male Cancer Survivors’ Coping Strategies. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2019, 41, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powazki, R.D. The Family Conference in Oncology: Benefits for The Patient, Family, and Physician. Semin. Oncol. 2011, 38, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, C.L. Family Communication and Decision Making at the End of Life: A Literature Review. Palliat. Support. Care 2015, 13, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keim, M.C.; Lehmann, V.; Shultz, E.L.; Winning, A.M.; Rausch, J.R.; Barrera, M.; Jo Gilmer, M.; Murphy, L.K.; Vannatta, K.A.; Compas, B.E.; et al. Parent–Child Communication and Adjustment Among Children With Advanced and Non-Advanced Cancer in the First Year Following Diagnosis or Relapse. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2017, 42, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, A.; Dalton, L.; Rapa, E.; Bluebond-Langner, M.; Hanington, L.; Stein, K.F.; Ziebland, S.; Rochat, T.; Harrop, E.; Kelly, B.; et al. Communication with Children and Adolescents about The Diagnosis of Their Won Life-Threatening Condition. Lancet 2019, 393, 1150–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, M.J.; Rodriguez, E.M.; Miller, K.S.; Gerhardt, C.A.; Vannatta, K.; Saylor, M.; Scheule, C.M.; Compas, B.E. Direct Observation of Mother-Child Communication in Pediatric Cancer: Assessment of Verbal and Non-Verbal Behavior and Emotion. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2011, 36, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Ghriwati, N.; Albee, M.; Brodsky, C.; Hocking, M.C. Patterns of Family Relationships in Pediatric Oncology: Implications for Children’s Adjustment upon Treatment Completion. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 6751–6759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips-Salimi, C.R.; Robb, S.L.; Monahan, P.O.; Dossey, A.; Haase, J.E. Perceptions of Communication, Family Adaptability and Cohesion: A Comparison of Adolescents Newly Diagnosed with Cancer and Their Parents. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2014, 26, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillery, R.; Willard, V.W.; Howard Sharp, K.M.; Klages, K.L.; Long, A.M.; Phipps, S. Impact of the Parent-child Relationship on Psychological and Social Resilience in Pediatric Cancer Patients. Psychooncology 2020, 29, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, A.; Taggi-Pinto, A.; Sahler, O.J.Z.; Alderfer, M.A.; Devine, K.A. Problem-solving Skills, Parent–Adolescent Communication, Dyadic Functioning, and Distress among Adolescents with Cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2018, 65, e26951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Harper, F.; Penner, L.; Swanson, K.; Santacroce, S. Parents’ Verbal and Nonverbal Caring Behaviors and Child Distress During Cancer-Related Port Access Procedures: A Time-Window Sequential Analysis. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2017, 44, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.; Choi, E.K.; Lyu, C.J.; Han, J.W.; Hahn, S.M. Family Resilience Factors Affecting Family Adaptation of Children with Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2022, 56, 102078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greeff, A.P.; Vansteenwegen, A.; Geldhof, A. Resilience in Families with a Child with Cancer. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2014, 31, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrios, P.; Enesco, I.; Varea, E. Emotional Experience and Type of Communication in Oncological Children and Their Mothers: Hearing Their Testimonies Through Interviews. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 834312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornblith, A.B.; Regan, M.M.; Kim, Y.; Greer, G.; Parker, B.; Bennett, S.; Winer, E. Cancer-related Communication between Female Patients and Male Partners Scale: A Pilot Study. Psychooncology 2006, 15, 780–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, J.R.; Stewart, S.L.; Johnston, M.; Banks, P.; Fobair, P. Sources of Support and the Physical and Mental Well-Being of Young Women with Breast Cancer. Soc. Sci. Med. 2001, 53, 1513–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leschak, C.J.; Eisenberger, N.I. Two Distinct Immune Pathways Linking Social Relationships With Health: Inflammatory and Antiviral Processes. Psychosom. Med. 2019, 81, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning-Walsh, J. Social Support as a Mediator Between Symptom Distress and Quality of Life in Women With Breast Cancer. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2005, 34, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochayon, L.; Tunin, R.; Yoselis, A.; Kadmon, I. Symptoms of Hormonal Therapy and Social Support: Is There a Connection? Comparison of Symptom Severity, Symptom Interference and Social Support among Breast Cancer Patients Receiving and Not Receiving Adjuvant Hormonal Treatment. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2015, 19, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner-Cobb, J.M.; Sephton, S.E.; Koopman, C.; Blake-Mortimer, J.; Spiegel, D. Social Support and Salivary Cortisol in Women With Metastatic Breast Cancer. Psychosom. Med. 2000, 62, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, H.; Haase, J.; Docherty, S.L. Parent-Child Communication in a Childhood Cancer Context: A Literature Review. Pediatr. Nurs. 2019, 45, 129–141. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne, J.C.; Racioppo, M.W. Never the Twain Shall Meet? Closing the Gap between Coping Research and Clinical Intervention Research. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldsmith, D.J.; Miller, G.A. Should I Tell You How I Feel? A Mixed Method Analysis of Couples’ Talk about Cancer. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2015, 43, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S.; Wolfe, J.; Samsel, C. The Impact of Cancer and Its Treatment on the Growth and Development of the Pediatric Patient. Curr. Pediatr. Rev. 2017, 13, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keijsers, L.; Poulin, F. Developmental Changes in Parent–Child Communication throughout Adolescence. Dev. Psychol. 2013, 49, 2301–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, K.P.; Mowbray, C.; Pyke-Grimm, K.; Hinds, P.S. Identifying a Conceptual Shift in Child and Adolescent-Reported Treatment Decision Making: “Having a Say, as I Need at This Time”. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2017, 64, e26262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wysocki, T. Introduction to the Special Issue: Direct Observation in Pediatric Psychology Research. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2015, 40, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorney, J.M.; McMurtry, C.M.; Chambers, C.T.; Bakeman, R. Developing and Modifying Behavioral Coding Schemes in Pediatric Psychology: A Practical Guide. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2015, 40, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, L.K.; Murray, C.B.; Compas, B.E. Topical Review: Integrating Findings on Direct Observation of Family Communication in Studies Comparing Pediatric Chronic Illness and Typically Developing Samples. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2017, 42, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swallow, V.; Macfadyen, A.; Santacroce, S.J.; Lambert, H. Fathers’ Contributions to the Management of Their Child’s Long-term Medical Condition: A Narrative Review of the Literature. Health Expect. 2012, 15, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNaughton, J.; Niedzwiecki, C.K. Gender Differences in Parent Child Communication Patterns. J. Undergrad. Res. 2000, 3, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, B.L.; Woods, S.B.; Sengupta, S.; Nair, T. The Biobehavioral Family Model: An Evidence-Based Approach to Biopsychosocial Research, Residency Training, and Patient Care. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 725045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelada, L.; Wakefield, C.E.; Doolan, E.L.; Drew, D.; Wiener, L.; Michel, G.; Cohn, R.J. Grandparents of Children with Cancer: A Controlled Comparison of Perceived Family Functioning. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 2087–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyle, M. The Expression of Emotion. In Bodily Communication, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, J.M. Family Resilience to the Challenge of a Child’s Disability. Pediatr. Ann. 1991, 20, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics of Verbal Communication | Associated Psychological–Behavioral Outcomes |

|---|---|

| Affirming [37,38] | Better family adaptation |

| Open [26,33,37] | Less anxiety, less depression, better family adaptation |

| Satisfying [33] | Better family adjustment and cohesion |

| Maternal validation [8] | Lower PTSS |

| Avoiding assumptions [36] | Less behavioral and verbal distress during procedure |

| Believing what the other says [36] | Less behavioral and verbal distress during procedure |

| Quality of information shared [34] | Lower level of PTSS Less internalizing symptoms, Increased level of social emotional competencies |

| Low discord [32] | Better peer relationships, less externalizing problems |

| Truthful, honest communication [39] | Reduced fear |

| Characteristics of Nonverbal Communication | Associated Psychological–Behavioral Outcomes |

| Eye contact [36] | Less behavioral and verbal distress |

| Being physically close enough to touch [36] | More cooperative behavior during procedure |

| Acknowledging behavior [8] | Lower PTSS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Son, H.; Kim, N. Therapeutic Parent–Child Communication and Health Outcomes in the Childhood Cancer Context: A Scoping Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 2152. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16112152

Son H, Kim N. Therapeutic Parent–Child Communication and Health Outcomes in the Childhood Cancer Context: A Scoping Review. Cancers. 2024; 16(11):2152. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16112152

Chicago/Turabian StyleSon, Heeyeon, and Nani Kim. 2024. "Therapeutic Parent–Child Communication and Health Outcomes in the Childhood Cancer Context: A Scoping Review" Cancers 16, no. 11: 2152. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16112152

APA StyleSon, H., & Kim, N. (2024). Therapeutic Parent–Child Communication and Health Outcomes in the Childhood Cancer Context: A Scoping Review. Cancers, 16(11), 2152. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16112152