Beam Position Projection Algorithms in Proton Pencil Beam Scanning

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

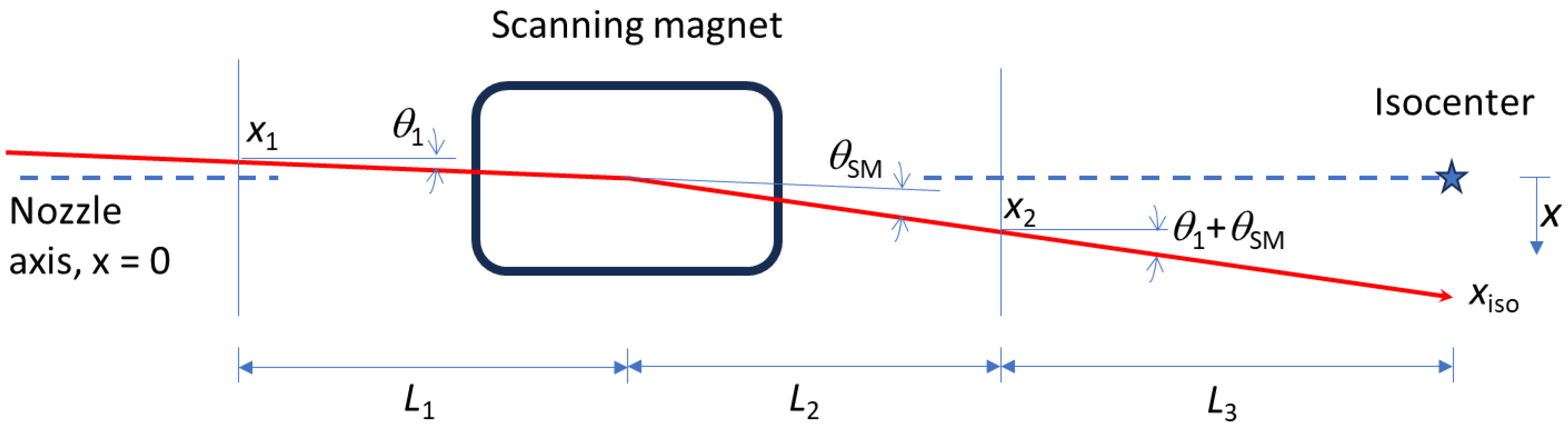

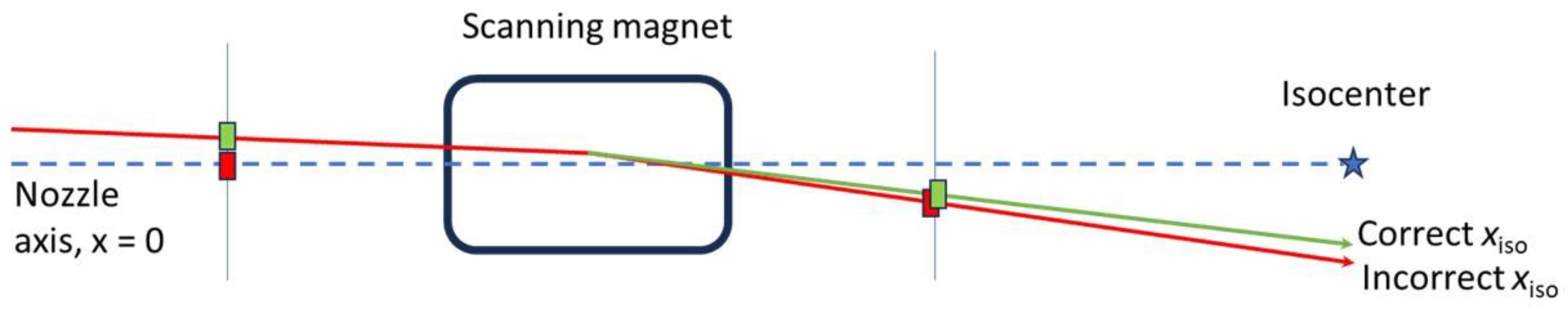

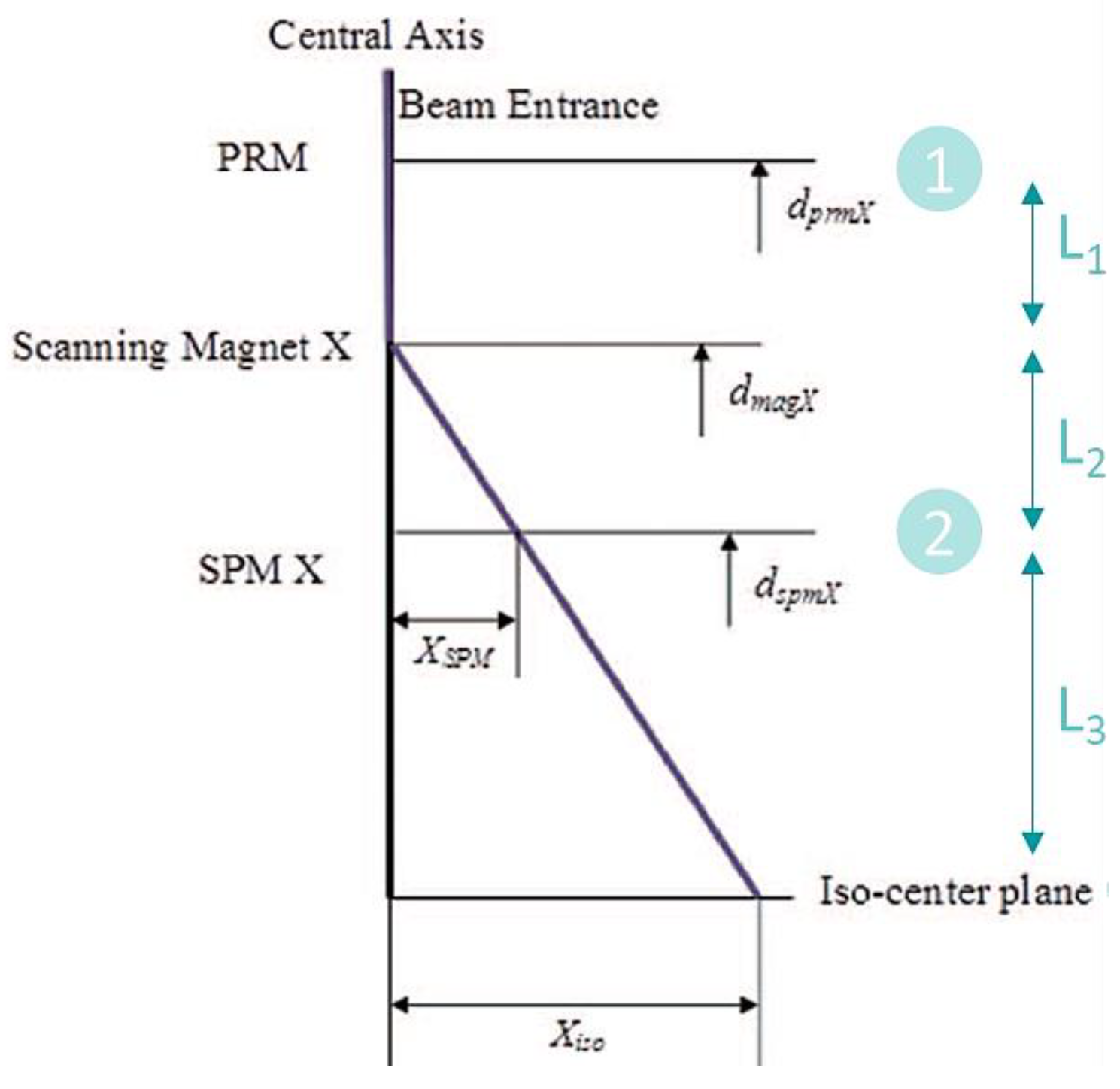

2.1. Beam Trajectory in a PBS Nozzle

2.2. Algorithm A1: x1, x2, and θSM Are Constrained Variables; θ1 Is the Eliminated Variable

2.3. Algorithm A2: x1, x2, and θ1 Are Constrained Variable, θSM Is the Eliminated Variable

2.4. Algorithm A3: x2, θSM, and θ1 Are Constrained Variables; x1 Is the Eliminated Variable

2.5. Algorithm A4: x1, θSM, and θ1 Are Constrained Variables; x2 Is the Eliminated Variable

2.6. Nozzle Configuration

- After = IC downstream of SM;

- Before = IC upstream of SM.

2.7. Error Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

- The small nozzle has larger total uncertainty than the large nozzle for the best algorithm in each scenario, largely due to the some of the demagnifications from the longer lengths between constrained positions. Instrumentation in smaller nozzles may need to be more precise to achieve the same level of uncertainty in the projection.

- ICs far from the isocenter contribute more to multiple-Coulomb scattering (MCS) which increases the pencil beam size.

- Online position correction algorithms should remember the prior correction after each spill and/or layer change until the end of the beam, and the beam current should be modulated to zero while the SM correction is being applied and turned back on automatically. This can be seen to be optimal by considering random and systematic position uncertainties. In the case of random uncertainties, there are pauses with each spill and/or layer change independent of the approach used. In the case of systematic position uncertainties, there is only one position correction needed if the prior correction is remembered and applied for the whole beam.

- Tuning pulses may help to make a more accurate position projection. These tuning pulses can be delivered with the scanning magnets set to zero, with the intention of centering the beam without θSM in the projection, and then adding scanning afterward. The projection in this case would be similar to that shown in Figure 3. While this method can help reduce uncertainties, care should be taken to make sure the effect of residual magnetism in the scanning magnets is negligible, and the amount of extra dose delivered to the patient is negligible.

- There must be redundant devices or checks on the performance of the nozzle instruments when performing online beam position corrections.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paganetti, H. Proton Beam Therapy; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-0-7503-1370-4. [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira, L.M.; Jemal, A.; Yabroff, K.R.; Efstathiou, J.A. Assessment of Proton Beam Therapy Use among Patients with Newly Diagnosed Cancer in the US, 2004–2018. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e229025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, M.; Chen, L.; Zhang, J.; Qiu, X. Pure Proton Therapy for Skull Base Chordomas and Chondrosarcomas: A Systematic Review of Clinical Experience. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1016857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dastgheyb, S.S.; Dreyfuss, A.D.; LaRiviere, M.J.; Mohiuddin, J.J.; Baumann, B.C.; Shabason, J.; Lustig, R.A.; Dorsey, J.F.; Lin, A.; Grady, S.M.; et al. A Prospective Phase I/II Clinical Trial of High-Dose Proton Therapy for Chordomas and Chondrosarcomas. Adv. Radiat. Oncol. 2024, 9, 101456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, K.; Gulidov, I.; Koryakin, S.; Smyk, D.; Makeenkova, T.; Gogolin, D.; Lepilina, O.; Golovanova, O.; Semenov, A.; Dujenko, S.; et al. Proton Therapy with a Fixed Beamline for Skull-Base Chordomas and Chondrosarcomas: Outcomes and Toxicity. Radiat. Oncol. 2021, 16, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.H.; Wang, Z.; Wong, W.W.; Murad, M.H.; Buckey, C.R.; Mohammed, K.; Alahdab, F.; Altayar, O.; Nabhan, M.; Schild, S.E.; et al. Charged Particle Therapy versus Photon Therapy for Paranasal Sinus and Nasal Cavity Malignant Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 1027–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, D.C.; Bizzocchi, N.; Bolsi, A.; Jenkinson, M.D. Proton Therapy for Intracranial Meningioma for the Treatment of Primary/Recurrent Disease Including Re-Irradiation. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 558845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeberg, S.; Harrabi, S.B.; Verma, V.; Bernhardt, D.; Grau, N.; Debus, J.; Rieken, S. Treatment of Meningioma and Glioma with Protons and Carbon Ions. Radiat. Oncol. 2017, 12, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.Y.; Fan, K.H. Proton Therapy for Prostate Cancer: Current State and Future Perspectives. Br. J. Radiol. 2022, 95, 20210670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa, A.J.; Thames, H.D.; Sanders, J.W.; Choi, S.L.; Nguyen, Q.N.; Mok, H.; Ron Zhu, X.; Shah, S.; Mayo, L.L.; Hoffman, K.E.; et al. Proton Therapy for the Management of Localized Prostate Cancer: Long-Term Clinical Outcomes at a Comprehensive Cancer Center. Radiother. Oncol. 2023, 188, 109854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vyfhuis, M.A.L.; Onyeuku, N.; Diwanji, T.; Mossahebi, S.; Amin, N.P.; Badiyan, S.N.; Mohindra, P.; Simone, C.B. Advances in Proton Therapy in Lung Cancer. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjyshi, O.; Liao, Z. Proton Therapy for Locally Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Br. J. Radiol. 2020, 93, 20190378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shioyama, Y.; Tokuuye, K.; Okumura, T.; Kagei, K.; Sugahara, S.; Ohara, K.; Akine, Y.; Ishikawa, S.; Satoh, H.; Sekizawa, K. Clinical Evaluation of Proton Radiotherapy for Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2003, 56, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, N.; Lee, A.; Lee, N.Y. Proton Beam Radiation Therapy Treatment for Head and Neck Cancer. Precis. Radiat. Oncol. 2022, 6, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharod, S.M.; Indelicato, D.J.; Rotondo, R.L.; Mailhot-Vega, R.B.; Uezono, H.; Morris, C.G.; Sandler, E.; Bradlery, J.A. Outcomes Following Proton Therapy for Ewing Sarcoma of the Cranium and Skull Base. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2019, 105, E635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demizu, Y.; Mizumoto, M.; Onoe, T.; Nakamura, N.; Kikuchi, Y.; Shibata, T.; Okimoto, T.; Sakurai, H.; Akimoto, T.; Ono, K.; et al. Proton Beam Therapy for Bone Sarcomas of the Skull Base and Spine: A Retrospective Nationwide Multicenter Study in Japan. Cancer Sci. 2017, 108, 972–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, K.K.; Daftari, I.K. Proton Therapy for the Management of Uveal Melanoma and Other Ocular Tumors. Chin. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 5, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakostas, T.D.; Lane, A.M.; Morrison, M.; Gragoudas, E.S.; Kim, I.K. Long-Term Outcomes after Proton Beam Irradiation in Patients with Large Choroidal Melanomas. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017, 135, 1191–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damato, B.; Kacperek, A.; Errington, D.; Heimann, H. Proton Beam Radiotherapy of Uveal Melanoma. Saudi J. Ophthalmol. 2013, 27, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paganetti, H.; Beltran, C.J.; Both, S.; Dong, L.; Flanz, J.B.; Furutani, K.M.; Grassberger, C.; Grosshans, D.R.; Knopf, A.-C.; Langendijk, J.A.; et al. Roadmap: Proton Therapy Physics and Biology. Phys. Med. Biol. 2020, 66, 05RM01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroni, E.; Bacher, R.; Blattmann, H.; Bohrinaer, T.; Coray, A.; Lomax, A.; Lin, S.; Munkel, G.; Scheib, S.; Schneider, U.; et al. The 200-MeV Proton Therapy Project at the Paul Scherrer Institute: Conceptual Design and Practical Realization. Med. Phys. 1995, 22, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanai, T.; Kawachi, K.; Kumamoto, Y.; Ogawa, H.; Yamada, T.; Matsuzawa, H.; Inada, T. Spot Scanning System for Proton Radiotherapy. Med. Phys. 1980, 7, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kooy, H.M.; Clasie, B.M.; Lu, H.M.; Madden, T.M.; Bentefour, H.; Depauw, N.; Adams, J.A.; Trofimov, A.V.; Demaret, D.; Delaney, T.F.; et al. A Case Study in Proton Pencil-Beam Scanning Delivery. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2010, 76, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordanengo, S.; Donetti, M. Dose Delivery Concept and Instrumentation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.00893. [Google Scholar]

- Arjomandy, B.; Taylor, P.; Ainsley, C.; Safai, S.; Sahoo, N.; Pankuch, M.; Farr, J.B.; Yong Park, S.; Klein, E.; Flanz, J.; et al. AAPM task group 224: Comprehensive proton therapy machine quality assurance. Med. Phys. 2019, 46, e678–e705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Psoroulas, S.; Bula, C.; Actis, O.; Weber, D.C.; Meer, D. A predictive algorithm for spot position corrections after fast energy switching in proton pencil beam scanning. Med. Phys. 2018, 45, 4806–4815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Sahoo, N.; Poenisch, F.; Suzuki, K.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Lee, A.K.; Gillin, M.T.; Zhu, X.R. Use of treatment log files in spot scanning proton therapy as part of patient-specific quality assurance. Med. Phys. 2013, 40, 021703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Clasie, B.; Lu, H.M.; Flanz, J.; Shen, T.; Jee, K.W. Impacts of gantry angle dependent scanning beam properties on proton PBS treatment. Phys. Med. Biol. 2017, 62, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.Q.; Lew, K.S.; Koh, C.W.Y.; Wibawa, A.; Master, Z.; Beltran, C.J.; Park, S.Y.; Furutani, K.M. The effect of spill change on reliable absolute dosimetry in a synchrotron proton spot scanning system. Med. Phys. 2023, 50, 4067–4078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.M. Error Analysis in Experimental Physical Science. Available online: https://faraday.physics.utoronto.ca/PVB/Harrison/ErrorAnalysis/ (accessed on 21 January 2023).

| Parameter | Uncertainty (1 σ) |

|---|---|

| x1 | 0.5 mm |

| x2 | 0.5 mm |

| θ1 | 1 mrad |

| θSM | 1 mrad |

| Parameter | Large Nozzle (mm) | Small Nozzle (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| L1 | 500 | 200 |

| L2 | 1000 | 200 |

| L3 | 500 | 500 |

| Uncertainty | Uncertainties (1 σ) Projected to xiso [mm] for Algorithms A1–A4 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large Nozzle | Small Nozzle | |||||||

| A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | |

| θ1 | 0 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 2 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.9 |

| θSM | 0.17 | 0 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 0.25 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| x1 | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.63 | 1.25 | 0 | 0.5 |

| x2 | 0.67 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0 | 1.13 | 1.75 | 0.5 | 0 |

| Total | 0.71 | 0.83 | 0.87 | 2.55 | 1.31 | 2.21 | 0.87 | 1.24 |

| Nozzle Configuration | Offline Variables | Total Offline Uncertainty (1 σ) in xiso [mm] for Algorithms A1–A4 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large Nozzle | Small Nozzle | ||||||||

| A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | ||

| IC Before and After | θ1 (+θSM) | 0 (0.17) | 0.25 (0.25) | 0.5 (0.71) | 2 (2.50) | 0 (0.25) | 0.5 (0.50) | 0.5 (0.71) | 0.9 (1.14) |

| IC After | θ1, x1 (+θSM) | 0.17 (0.24) | 0.35 (0.35) | 0.5 (0.71) | 2.06 (2.55) | 0.63 (0.67) | 1.35 (1.35) | 0.5 (0.71) | 1.03 (1.24) |

| IC Before | θ1, x2 (+θSM) | 0.67 (0.69) | 0.79 (0.79) | 0.71 (0.87) | 2 (2.50) | 1.13 (1.15) | 1.82 (1.82) | 0.71 (0.87) | 0.9 (1.14) |

| Uncertainty | Large Nozzle | Small Nozzle |

|---|---|---|

| x1 | 0.17 | 0.63 |

| x2 | 0.67 | 1.13 |

| Total offline | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 0.69 | 1.29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nesteruk, K.P.; Bradley, S.G.; Kooy, H.M.; Clasie, B.M. Beam Position Projection Algorithms in Proton Pencil Beam Scanning. Cancers 2024, 16, 2098. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16112098

Nesteruk KP, Bradley SG, Kooy HM, Clasie BM. Beam Position Projection Algorithms in Proton Pencil Beam Scanning. Cancers. 2024; 16(11):2098. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16112098

Chicago/Turabian StyleNesteruk, Konrad P., Stephen G. Bradley, Hanne M. Kooy, and Benjamin M. Clasie. 2024. "Beam Position Projection Algorithms in Proton Pencil Beam Scanning" Cancers 16, no. 11: 2098. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16112098

APA StyleNesteruk, K. P., Bradley, S. G., Kooy, H. M., & Clasie, B. M. (2024). Beam Position Projection Algorithms in Proton Pencil Beam Scanning. Cancers, 16(11), 2098. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16112098