Lung Clearance Index as a Screening Parameter of Pulmonary Impairment in Patients under Immune Checkpoint Therapy: A Pilot Study

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethics Approval

2.2. Setting and Participants

2.3. Pulmonary Function Testing

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Population Characteristics and ICB Treatment Details

3.2. Pulmonary irAEs

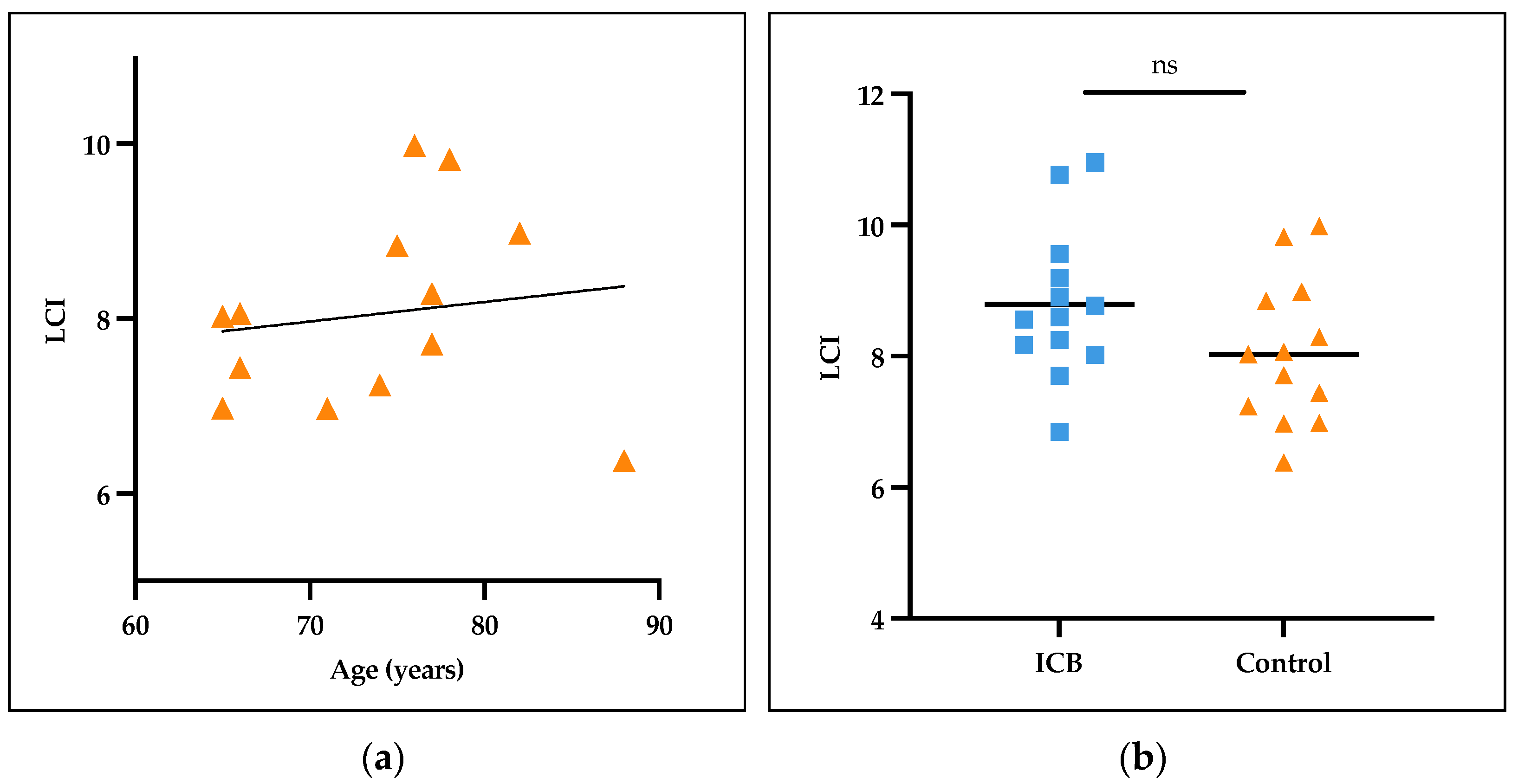

3.3. Normal Values for LCI in Collectives Aged > 65 Years

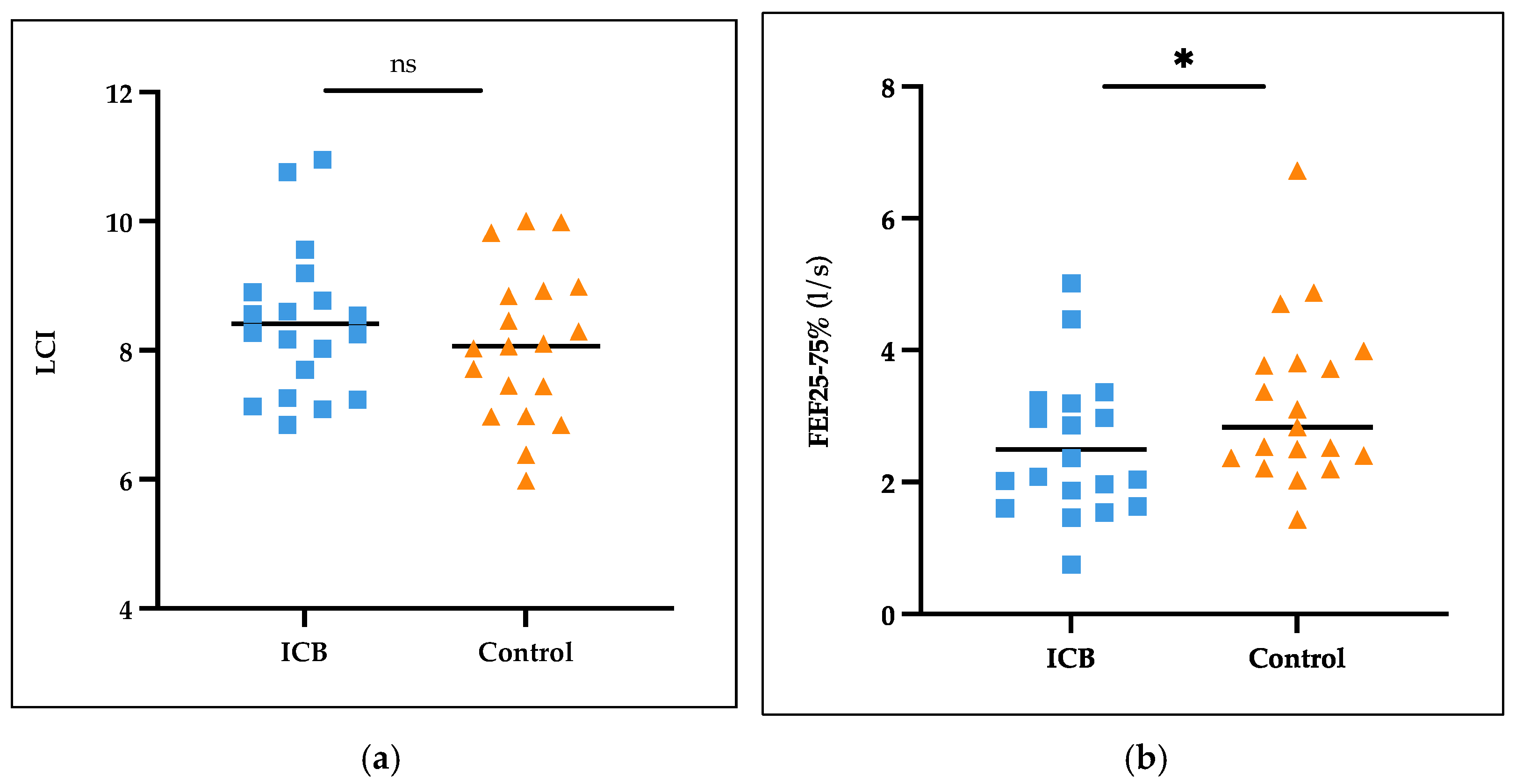

3.4. Lung Function in ICB Patients and Controls

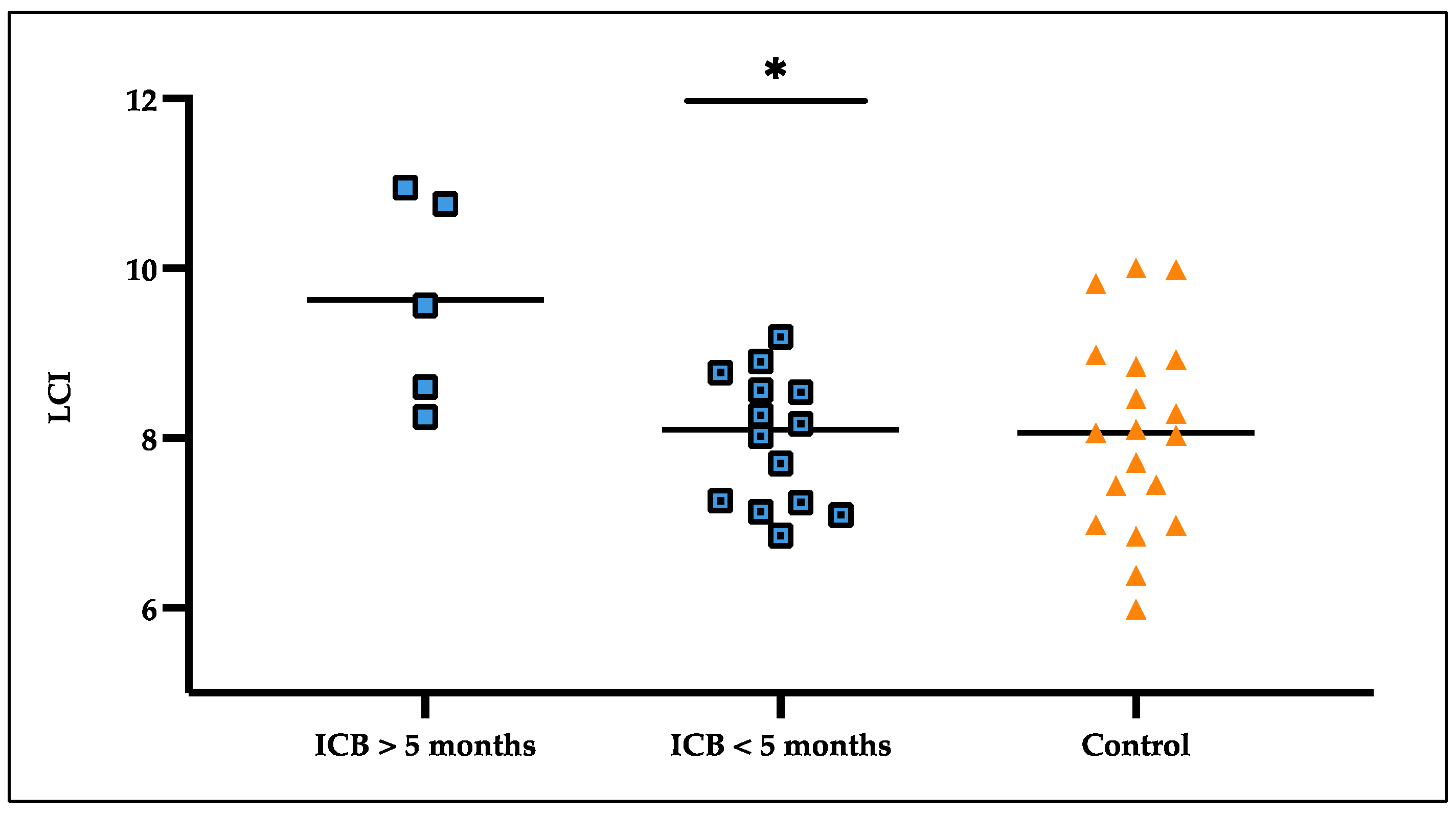

3.5. LCI Deteriorated over Treatment Time

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Topalian, S.L.; Hodi, F.; Brahmer, J.; Gettinger, S.; Smith, D.; McDermott, D.; Powderly, J.; Carvajal, R.; Sosman, J.; Atkins, M. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti–PD-1 antibody in cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 2443–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barone, A.; Hazarika, M.; Theoret, M.; Mishra-Kalyani, P.; Chen, H.; He, K.; Sridhara, R.; Subramaniam, S.; Pfuma, E.; Wang, Y.; et al. FDA Approval Summary: Pembrolizumab for the Treatment of Patients with Unresectable or Metastatic Melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 5661–5665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazarika, M.; Chuk, M.; Theoret, M.; Mushti, S.; He, K.; Weis, S.; Putman, A.; Helms, W.; Cao, X.; Li, H.; et al. U.S. FDA Approval Summary: Nivolumab for Treatment of Unresectable or Metastatic Melanoma Following Progression on Ipilimumab. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 3484–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizvi, N.A.; Mazières, J.; Planchard, D.; Stinchcombe, T.; Dy, G.; Antonia, S.; Horn, L.; Lena, H.; Minenza, E.; Mennecier, B. Activity and safety of nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, for patients with advanced, refractory squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 063): A phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimm, M.-O.; Oppel-Heuchel, H.; Foller, S. Therapie mit PD-1/PD-L1-und CTLA-4-Immun-Checkpoint-Inhibitoren. Urologe 2018, 57, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidoo, J.; Wang, X.; Woo, K.; Iyriboz, T.; Halpenny, D.; Cunningham, J.; Chaft, J.; Segal, N.; Callahan, M.; Lesokhin, A.; et al. Pneumonitis in Patients Treated with Anti-Programmed Death-1/Programmed Death Ligand 1 Therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmer, L.; Goldinger, S.M.; Hofmann, L.; Loquai, C.; Ugurel, S.; Thomas, M.; Schwab, C.; Gutzmer, R.; Hörber, C.; Hassel, J.C.; et al. Neurological, respiratory, musculoskeletal, cardiac and ocular side-effects of anti-PD-1 therapy. Eur. J. Cancer 2016, 60, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishino, M.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Hatabu, H.; Ramaiya, N.H.; Hodi, F.S. Incidence of Programmed Cell Death 1 Inhibitor–Related Pneumonitis in Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidoo, J.; Wang, X.; Woo, K.M.; Iyriboz, T.; Halpenny, D.; Cunningham, J.; Chaft, J.E.; Segal, N.H.; Hellmann, M.D.; Gomez, D.R.; et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 2375–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Disayabutr, S.; Calfee, C.S.; Collard, H.R.; Wolters, P.J. Interstitial lung diseases in the hospitalized patient. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Liberal, J.; Kordbacheh, T.; Larkin, J. Safety of pembrolizumab for the treatment of melanoma. Expert. Opin. Drug Saf. 2015, 14, 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, J.S.; D’Angelo, S.P.; Minor, D.; Hodi, F.S.; Gutzmer, R.; Neyns, B.; Hoeller, C.; Khushalani, N.I.; Miller, W.H.; Lao, C.D.; et al. Safety, efficacy, and biomarkers of nivolumab with vaccine in ipilimumab-refractory or-naive melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brahmer, J.R.; Lacchetti, C.; Schneider, B.J.; Atkins, M.B.; Brassil, K.J.; Caterino, J.M.; Chau, I.; Ernstoff, M.S.; Feeding, K.L.; Fenton, M.J.; et al. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidoo, J.; Page, D.B.; Wolchok, J.D.; Brahmer, J.R.; Ott, P.A.; Hodi, F.S.; Postow, M.A.; Hellmann, M.D. Chronic immune checkpoint inhibitor pneumonitis. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delaunay, M.; Prévot, G.; Collot, S.; Guilleminault, L.; Didier, A.; Mazières, J. Immune-checkpoint inhibitors associated with interstitial lung disease in cancer patients. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50, 1700050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spagnolo, P.; Lee, J.S.; Sverzellati, N.; Rossi, G.; Cottin, V. The lung in rheumatoid arthritis: Focus on interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018, 70, 1544–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzen, D.; Schadendorf, D.; Roengvoraphoj, O.; Singh, A.; Neumuth, T.; Hohenstein, B.; Koschny, R.; Habedank, D.; Schmidt, J.; Dickgreber, N.; et al. Ipilimumab and early signs of pulmonary toxicity in patients with metastastic melanoma: A prospective observational study. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2018, 67, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houltz, B.; Anderson, M.; Cain, M.; Cooper, B.G.; Crichton, D.; Enright, P.; Gulsvik, A.; Hall, G.L.; Hankinson, J.L.; Johnston, R.; et al. Tidal N2 washout ventilation inhomogeneity indices in a reference population aged 7–70 years. Eur. Respir. Soc. 2012, 40 (Suppl. S56), P3797. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, B.G.; Stocks, J.; Hall, G.L.; Culver, B.; Steenbruggen, I.; Carter, K.W.; Thompson, B.R.; Graham, B.L. The Global Lung Function Initiative (GLI) Network: Bringing the world’s respiratory reference values together. Breathe 2017, 13, e56–e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonem, S.; Burton, J.; Robinson, P.; Cassidy, D.; Fowler, S.J.; Bayliss, S.; Jones, M.; Siddiqui, S.; Sapey, E.; Holmes, S.; et al. Lung clearance index in adults with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Respir. Res. 2014, 15, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, M.R.; Hankinson, J.; Brusasco, V.; Burgos, F.; Casaburi, R.; Coates, A.; Crapo, R.; Enright, P.; Van der Grinten, C.P.; Gustafsson, P.; et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur. Respir. J. 2005, 26, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.R.; Crapo, R.; Hankinson, J.; Brusasco, V.; Burgos, F.; Casaburi, R.; Coates, A.; Enright, P.; Van der Grinten, C.P.; Gustafsson, P.; et al. General considerations for lung function testing. Eur. Respir. J. 2005, 26, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanger, J.; Clausen, J.L.; Coates, A.; Pedersen, O.F.; Brusasco, V.; Burgos, F.; Casaburi, R.; Crapo, R.; Enright, P.; Van der Grinten, C.P.; et al. Standardisation of the measurement of lung volumes. Eur. Respir. J. 2005, 26, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacIntyre, N.; Crapo, R.O.; Viegi, G.; Johnson, D.C.; van der Grinten, C.P.; Brusasco, V.; Burgos, F.; Casaburi, R.; Coates, A.; Enright, P.; et al. Standardisation of the single-breath determination of carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur. Respir. J. 2005, 26, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrino, R.; Viegi, G.; Brusasco, V.; Crapo, R.O.; Burgos, F.; Casaburi, R.; Coates, A.; van der Grinten, C.P.; Gustafsson, P.; Hankinson, J.; et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur. Respir. J. 2005, 26, 948–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quanjer, P.H.; Stanojevic, S.; Cole, T.J.; Baur, X.; Hall, G.L.; Culver, B.H.; Enright, P.L.; Hankinson, J.L.; Ip, M.S.; Zheng, J.; et al. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3–95-year age range: The global lung function 2012 equations. Eur. Respir. J. 2012, 40, 1324–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, D.S.; Lee, J.H.; Kang, H.W.; Jo, W.J.; Kim, H.J.; Shin, K.C.; Lee, J.M.; Kang, S.M.; Jeon, E.J.; Kim, C.H.; et al. FEF25–75% Values in Patients with Normal Lung Function Can Predict the Development of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Int. J. Chron. Obs. Pulmon. Dis. 2020, 15, 2913–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quanjer, P.H.; Weiner, D.J.; Pretto, J.J.; Brazzale, D.J.; Boros, P.W. Measurement of FEF25–75% and FEF75% does not contribute to clinical decision making. Eur. Respir. J. 2014, 43, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelb, A.F.; Williams, A.J.; Zamel, N. Spirometry: FEV, vs. FEF25–75 Percent. Chest 1983, 84, 473–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horsley, A.R.; Gustafsson, P.M.; Macleod, K.A.; Saunders, C.; Greening, A.P.; Porteous, D.M.; Davies, J.C.; Cunningham, S.; Fardon, T.C.; McCormack, A. Lung clearance index is a sensitive, repeatable and practical measure of airways disease in adults with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 2008, 63, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lum, S.; Stocks, J.; Stanojevic, S.; Wade, A.; Robinson, P.; Gustafsson, P. Early detection of cystic fibrosis lung disease: Multiple-breath washout versus raised volume tests. Thorax 2007, 62, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khair, D.O.; Bax, H.J.; Mele, S.; Crescioli, S.; Pellizzari, G.; Khiabani, A.Z.; Greek, R.; Stavraka, C.; Spicer, J.F.; Tutt, A.N.J.; et al. Combining Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: Established and Emerging Targets and Strategies to Improve Outcomes in Melanoma. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkin, J.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Grob, J.J.; Cowey, C.L.; Lao, C.D.; Schadendorf, D.; Dummer, R.; Smylie, M.; Rutkowski, P.; et al. Five-Year Survival with Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1535–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanojevic, S.; Bilton, D.; Lindblad, A.; Stocks, J.; Aurora, P.; Gustafsson, P. Progression of Lung Disease in Preschool Patients with Cystic Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 195, 1216–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aurora, P.; Gustafsson, P.M.; Bush, A.; Lindblad, A.; Oliver, C.; Wallis, C.; Price, J.; Stroobant, J.; Carr, S.B.; Stocks, J. Multiple-breath washout as a marker of lung disease in preschool children with cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2005, 171, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usemann, J.; Yammine, S.; Singer, F.; Latzin, P. Inert gas washout: Background and application in various lung diseases. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2017, 147, w14483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attanasi, M.; Lucidi, V.; Montesanto, C.; Bertini, F.; Consalvo, E.; Lanciotti, M.; Rapino, D.; Di Pillo, S.; Parisi, P.; Mohn, A.; et al. Lung function in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: A cross-sectional analysis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2019, 54, 1242–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafsson, P.M.; Aurora, P.; Lindblad, A. Evaluation of ventilation maldistribution as an early indicator of lung disease in children with cystic fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2003, 22, 972–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hildebrandt, J.; Rahn, A.; Keßler, A.; Speth, F.; Fischer, D.-C.; Ballmann, M. Lung Clearance Index (LCI) and diffusion capacity of the lung (DLCO) in children with rheumatic disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 56 (Suppl. S64), 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, S.I.; Gappa, M. Lung clearance index: Clinical and research applications in children. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2011, 12, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parisi, G.F.; Manti, S.; Papale, M.; Licari, A.; Marseglia, G.L.; Leonardi, S. Lung clearance index: A new measure of late lung complications of cancer therapy in children. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2020, 55, 3450–3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schachter, J.; Ribas, A.; Long, G.V.; Arance, A.; Grob, J.J.; Mortier, L.; Daud, A.; Carlino, M.S.; McNeil, C.; Lotem, M.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab for advanced melanoma: Final overall survival results of a multicentre, randomised, open-label phase 3 study (KEYNOTE-006). Lancet 2017, 390, 1853–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, J.S.; Ribas, A.; Long, G.V.; Arance, A.; Grob, J.J.; Mortier, L.; Daud, A.; Carlino, M.S.; McNeil, C.; Lotem, M.; et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): A randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodi, F.S.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Grob, J.J.; Rutkowski, P.; Cowey, C.L.; Lao, C.D.; Chesney, J.; Robert, C.; Schadendorf, D.; et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab or nivolumab alone versus ipilimumab alone in advanced melanoma (CheckMate 067): 4-year outcomes of a multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 1480–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clinical Values | ICB-Patients | Controls |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 19 | 19 |

| Age, years | 66.8 (14.3) | 67.2 (13.1) |

| Sex [f|m] | 7 [37%]|12 [63%] | 7 [37%]|12 [63%] |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 (SD) | 28.7 (4.7) | 26.8 (3.6) |

| Previous smokers | 3 [16%] | 0 |

| Pack-years, years (SD) | 10 (4.1) | 0 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Arterial hypertension | 13 [68%] | 6 [32%] |

| Hypothyreosis | 6 [32%] | 2 [11%] |

| ECOG-Status: 0|1|2 | 17 [68%]|1 [5%]|1 [5%] | 19 [100%]|0|0 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Melanoma | 17 [89%] | |

| cSCC | 2 [11%] | |

| Pulmonal metastases | 6 [32%] | |

| ICB-Therapy | ||

| Nivolumab 240 mg/480 mg | 3 [16%] | |

| Pembrolizumab 200 mg | 9 [47%] | |

| Cemiplimab 350 mg | 2 [11%] | |

| Nivolumab 1 mg/kg body weight plus Ipilimumab 3 mg/kg body weight | 5 [26%] | |

| Therapy setting | ||

| adjuvant | 7 [37%] | |

| metastatic | 12 [63%] | |

| Time under ongoing ICB-therapy at point of testing, weeks (SD) | 19.1 (9.9) | |

| Number of cycles at point of testing (SD) | 6.5 (3.8) | |

| Laboratory values | ||

| LDH, U/L (SD) | 241.5 (77.5) | |

| S100, μg/L (SD) | 0.14 (0.15) | |

| CRP (SD) | 8.4 (10.6) | |

| Pulmonary function values | ||

| FVC, l (SD)|FCV, % predicted (SD) | 3.37 (1.03)|90.95 (16.18) | 3.54 (1.21)|87.68 (12.56) |

| FEV1, l (SD)|FEV1, % predicted (SD) | 2.62 (0.81)|92.58 (18.60) | 2.89 (0.98)|93.42 (13.77) |

| FEV1/FVC (SD)|FEV1/FVC % predicted (SD) | 0.78 (0.06)|101.11 (8.09) | 0.82 (0.07)|106.05 (8.40) |

| FEF25–75%, l/s (SD)|FEF25–75%, % predicted (SD) | 2.49 (1.07)|110.21 (49.05) | 3.21 (1.26)|126.11 (37.30) |

| DLCO ml/min/mmHg (SD)|DLCO % predicted (SD) | 21.76 (4.39)|94.32 (18.63) | 22.87 (8.27)|94.63 (22.47) |

| FRC mb, l (SD) | 2.95 (0.91) | 2.82 (1.09) |

| LCI (SD) | 8.41 (1.15) | 8.07 (1.17) |

| - LCI ICB over 5 months (SD) | 9.63 (1.22) | |

| - LCI ICB under 5 months (SD) | 7.98 (0.77) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Steinbach, M.-L.C.; Eska, J.; Weitzel, J.; Görges, A.R.; Tietze, J.K.; Ballmann, M. Lung Clearance Index as a Screening Parameter of Pulmonary Impairment in Patients under Immune Checkpoint Therapy: A Pilot Study. Cancers 2024, 16, 2088. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16112088

Steinbach M-LC, Eska J, Weitzel J, Görges AR, Tietze JK, Ballmann M. Lung Clearance Index as a Screening Parameter of Pulmonary Impairment in Patients under Immune Checkpoint Therapy: A Pilot Study. Cancers. 2024; 16(11):2088. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16112088

Chicago/Turabian StyleSteinbach, Maya-Leonie C., Jakob Eska, Julia Weitzel, Alexandra R. Görges, Julia K. Tietze, and Manfred Ballmann. 2024. "Lung Clearance Index as a Screening Parameter of Pulmonary Impairment in Patients under Immune Checkpoint Therapy: A Pilot Study" Cancers 16, no. 11: 2088. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16112088

APA StyleSteinbach, M.-L. C., Eska, J., Weitzel, J., Görges, A. R., Tietze, J. K., & Ballmann, M. (2024). Lung Clearance Index as a Screening Parameter of Pulmonary Impairment in Patients under Immune Checkpoint Therapy: A Pilot Study. Cancers, 16(11), 2088. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16112088