Assessment of Segmentary Hypertrophy of Future Remnant Liver after Liver Venous Deprivation: A Single-Center Study

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

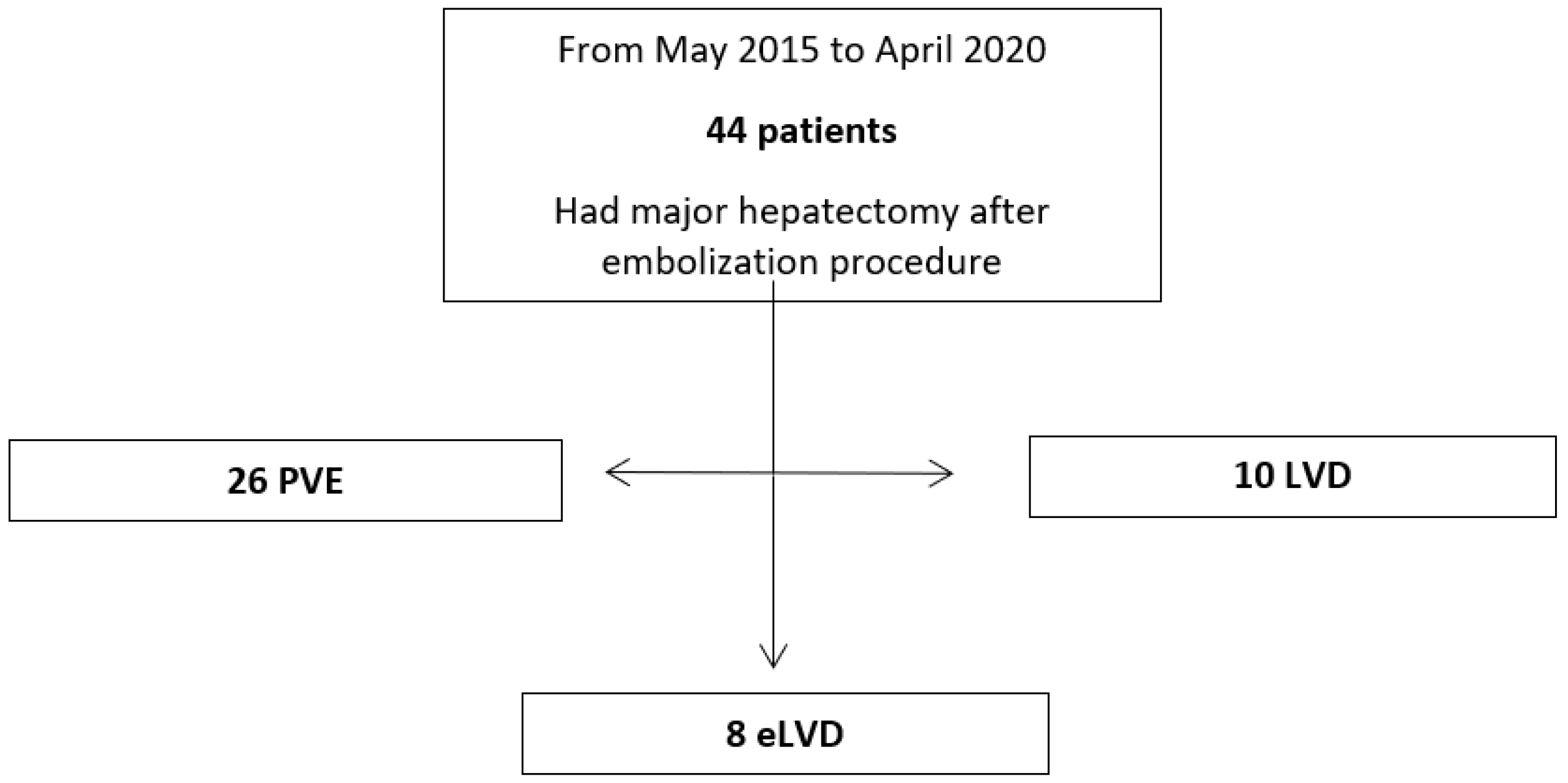

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Patient Selection

2.3. Choice of PVE versus LVD/eLVD

2.4. Radiological Procedure

2.5. Surgical Procedure

2.6. Data and Volume Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ Characteristics

3.2. Volume Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Belghiti, J.; Hiramatsu, K.; Benoist, S.; Massault, P.P.; Sauvanet, A.; Farges, O. Seven Hundred Forty-Seven Hepatectomies in the 1990s: An Update to Evaluate the Actual Risk of Liver Resection. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2000, 191, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarnagin, W.R.; Gonen, M.; Fong, Y.; DeMatteo, R.P.; Ben-Porat, L.; Little, S.; Corvera, C.; Weber, S.; Blumgart, L.H. Improvement in Perioperative Outcome After Hepatic Resection: Analysis of 1,803 Consecutive Cases Over the Past Decade. Ann. Surg. 2002, 236, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dokmak, S.; Ftériche, F.S.; Borscheid, R.; Cauchy, F.; Farges, O.; Belghiti, J. 2012 Liver Resections in the 21st Century: We Are Far from Zero Mortality. HPB 2013, 15, 908–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detroz, B.; Sugarbaker, P.H.; Knol, J.A.; Petrelli, N.; Hughes, K.S. Causes of Death in Patients Undergoing Liver Surgery. Cancer Treat. Res. 1994, 69, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmonds, P.C.; Primrose, J.N.; Colquitt, J.L.; Garden, O.J.; Poston, G.J.; Rees, M. Surgical Resection of Hepatic Metastases from Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review of Published Studies. Br. J. Cancer 2006, 94, 982–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanabe, G.; Sakamoto, M.; Akazawa, K.; Kurita, K.; Hamanoue, M.; Ueno, S.; Kobayashi, Y.; Mitue, S.; Ogura, Y.; Yoshidome, N.; et al. Intraoperative Risk Factors Associated with Hepatic Resection. Br. J. Surg. 1995, 82, 1262–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whemming, A. The Hippurate Ratio as an Indicator of Functional Hepatic Reserve for Resection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Cirrhotic Patients*1, *2. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2001, 5, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokoyama, Y.; Nagino, M.; Nimura, Y. Mechanisms of Hepatic Regeneration Following Portal Vein Embolization and Partial Hepatectomy: A Review. World J. Surg. 2007, 31, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guglielmi, A.; Ruzzenente, A.; Conci, S.; Valdegamberi, A.; Iacono, C. How Much Remnant Is Enough in Liver Resection? Dig. Surg. 2012, 29, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.S.; Garcia-Aroz, S.; Ansari, M.A.; Atiq, S.M.; Senter-Zapata, M.; Fowler, K.; Doyle, M.B.; Chapman, W.C. Assessment and Optimization of Liver Volume before Major Hepatic Resection: Current Guidelines and a Narrative Review. Int. J. Surg. 2018, 52, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, T.; Kubota, K. Preoperative portal vein embolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: Consensus and controversy. World J. Hepatol. 2016, 8, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Lienden, K.P.; van den Esschert, J.W.; de Graaf, W.; Bipat, S.; Lameris, J.S.; van Gulik, T.M.; van Delden, O.M. Portal Vein Embolization Before Liver Resection: A Systematic Review. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2013, 36, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abulkhir, A.; Limongelli, P.; Healey, A.J.; Damrah, O.; Tait, P.; Jackson, J.; Habib, N.; Jiao, L.R. Preoperative Portal Vein Embolization for Major Liver Resection: A Meta-Analysis. Ann. Surg. 2008, 247, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez, F.A.; Castaing, D.; Figueroa, R.; Allard, M.A.; Golse, N.; Pittau, G.; Ciacio, O.; Sa Cunha, A.; Cherqui, D.; Azoulay, D.; et al. Natural History of Portal Vein Embolization before Liver Resection: A 23-Year Analysis of Intention-to-Treat Results. Surgery 2018, 163, 1257–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chansangrat, J.; Keeratibharat, N. Portal vein embolization: Rationale, techniques, outcomes and novel strategies. Hepat. Oncol. 2021, 8, HEP42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnitzbauer, A.A.; Lang, S.A.; Goessmann, H.; Nadalin, S.; Baumgart, J.; Farkas, S.A.; Fichtner-Feigl, S.; Lorf, T.; Goralcyk, A.; Hörbelt, R.; et al. Right Portal Vein Ligation Combined With In Situ Splitting Induces Rapid Left Lateral Liver Lobe Hypertrophy Enabling 2-Staged Extended Right Hepatic Resection in Small-for-Size Settings. Ann. Surg. 2012, 255, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guiu, B.; Chevallier, P.; Denys, A.; Delhom, E.; Pierredon-Foulongne, M.-A.; Rouanet, P.; Fabre, J.-M.; Quenet, F.; Herrero, A.; Panaro, F.; et al. Simultaneous Trans-Hepatic Portal and Hepatic Vein Embolization before Major Hepatectomy: The Liver Venous Deprivation Technique. Eur. Radiol. 2016, 26, 4259–4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guiu, B.; Quenet, F.; Escal, L.; Bibeau, F.; Piron, L.; Rouanet, P.; Fabre, J.-M.; Jacquet, E.; Denys, A.; Kotzki, P.-O.; et al. Extended Liver Venous Deprivation before Major Hepatectomy Induces Marked and Very Rapid Increase in Future Liver Remnant Function. Eur. Radiol. 2017, 27, 3343–3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khayat, S.; Cassese, G.; Quenet, F.; Cassinotto, C.; Assenat, E.; Navarro, F.; Guiu, B.; Panaro, F. Oncological Outcomes after Liver Venous Deprivation for Colorectal Liver Metastases: A Single Center Experience. Cancers 2021, 13, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassese, G.; Troisi, R.I.; Khayat, S.; Quenet, F.; Tomassini, F.; Panaro, F.; Guiu, B. Liver Venous Deprivation versus Associating Liver Partition and Portal Vein Ligation for Staged Hepatectomy for Colo-Rectal Liver Metastases: A Comparison of Early and Late Kinetic Growth Rates, and Perioperative and Oncological Outcomes. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 43, 101812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassese, G.; Troisi, R.I.; Khayat, S.; Benoudifa, B.; Quenet, F.; Guiu, B.; Panaro, F. Liver Venous Deprivation Versus Portal Vein Embolization before Major Hepatectomy for Colorectal Liver Metastases: A Retrospective Comparison of Short- and Medium-Term Outcomes. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2023, 27, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strasberg, S.M.; Belghiti, J.; Clavien, P.-A.; Gadzijev, E.; Garden, J.O.; Lau, W.-Y.; Makuuchi, M.; Strong, R.W. The Brisbane 2000 Terminology of Liver Anatomy and Resections. HPB 2000, 2, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavien, P.A.; Petrowsky, H.; DeOliveira, M.L.; Graf, R. Strategies for safer liver surgery and partial liver transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 1545–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heil, J.; Schiesser, M.; Schadde, E. Current trends in regenerative liver surgery: Novel clinical strategies and experimental approaches. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 903825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiu, B.; Quenet, F.; Panaro, F.; Piron, L.; Cassinotto, C.; Herrerro, A.; Souche, F.-R.; Hermida, M.; Pierredon-Foulongne, M.-A.; Belgour, A.; et al. Liver Venous Deprivation versus Portal Vein Embolization before Major Hepatectomy: Future Liver Remnant Volumetric and Functional Changes. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 2020, 9, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Schadde, E. Hypertrophy and Liver Function in ALPPS: Correlation with Morbidity and Mortality. Visc. Med. 2017, 33, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrelid, E.; Jonas, E.; Tzortzakakis, A.; Dahlén, U.; Murquist, G.; Brismar, T.; Axelsson, R.; Isaksson, B. Dynamic Evaluation of Liver Volume and Function in Associating Liver Partition and Portal Vein Ligation for Staged Hepatectomy. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2017, 21, 967–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olthof, P.B.; Tomassini, F.; Huespe, P.E.; Truant, S.; Pruvot, F.-R.; Troisi, R.I.; Castro, C.; Schadde, E.; Axelsson, R.; Sparrelid, E.; et al. Hepatobiliary Scintigraphy to Evaluate Liver Function in Associating Liver Partition and Portal Vein Ligation for Staged Hepatectomy: Liver Volume Overestimates Liver Function. Surgery 2017, 162, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truant, S.; Baillet, C.; Deshorgue, A.C.; El Amrani, M.; Huglo, D.; Pruvot, F.-R. Contribution of Hepatobiliary Scintigraphy in Assessing ALPPS Most Suited Timing. Updates Surg. 2017, 69, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavriilidis, P.; Marangoni, G.; Ahmad, J.; Azoulay, D. Simultaneous Portal and Hepatic Vein Embolization Is Better than Portal Embolization or ALPPS for Hypertrophy of Future Liver Remnant before Major Hepatectomy: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2023, 22, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, F.; Zhang, W.; Feng, L. Efficacy and Safety of Different Options for Liver Regeneration of Future Liver Remnant in Patients with Liver Malignancies: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 20, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozkurt, E.; Sijberden, J.P.; Kasai, M.; Abu Hilal, M. Efficacy and Perioperative Safety of Different Future Liver Remnant Modulation Techniques: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. HPB 2024, 26, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, S.; Kamiyama, T.; Yokoo, H.; Orimo, T.; Wakayama, K.; Nagatsu, A.; Kakisaka, T.; Kamachi, H.; Abo, D.; Sakuhara, Y.; et al. Hepatic Hypertrophy and Hemodynamics of Portal Venous Flow after Percutaneous Transhepatic Portal Embolization. BMC Surg. 2019, 19, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asencio, J.M.; García-Sabrido, J.L.; López-Baena, J.A.; Olmedilla, L.; Peligros, I.; Lozano, P.; Morales-Taboada, Á.; Fernández-Mena, C.; Steiner, M.A.; Sola, E.; et al. Preconditioning by Portal Vein Embolization Modulates Hepatic Hemodynamics and Improves Liver Function in Pigs with Extended Hepatectomy. Surgery 2017, 161, 1489–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narula, N.; Aloia, T.A. Portal Vein Embolization in Extended Liver Resection. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2017, 402, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scatton, O.; Belghiti, J.; Dondero, F.; Goere, D.; Sommacale, D.; Plasse, M.; Sauvanet, A.; Farges, O.; Vilgrain, V.; Durand, F. Harvesting the Middle Hepatic Vein with a Right Hepatectomy Does Not Increase the Risk for the Donor. Liver Transpl. 2004, 10, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björnsson, B.; Hasselgren, K.; Røsok, B.; Larsen, P.N.; Urdzik, J.; Schultz, N.A.; Carling, U.; Fallentin, E.; Gilg, S.; Sandström, P.; et al. Segment 4 occlusion in portal vein embolization increase future liver remnant hypertrophy—A Scandinavian cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 75, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, C.J.; Ali, S.; Haq, H.; Luo, L.; Wyatt, J.I.; Toogood, G.J.; Lodge, J.P.A.; Patel, J.V. Segment 2/3 Hypertrophy Is Greater When Right Portal Vein Embolisation Is Extended to Segment 4 in Patients with Colorectal Liver Metastases: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2019, 42, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, K.; Kumamoto, T.; Matsuyama, R.; Takeda, K.; Nagano, Y.; Endo, I. Influence of Chemotherapy on Liver Regeneration Induced by Portal Vein Embolization or First Hepatectomy of a Staged Procedure for Colorectal Liver Metastases. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2010, 14, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturesson, C.; Keussen, I.; Tranberg, K.-G. Prolonged Chemotherapy Impairs Liver Regeneration after Portal Vein Occlusion—An Audit of 26 Patients. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2010, 36, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soykan, E.A.; Aarts, B.M.; Lopez-Yurda, M.; Kuhlmann, K.F.D.; Erdmann, J.I.; Kok, N.; van Lienden, K.P.; Wilthagen, E.A.; Beets-Tan, R.G.H.; van Delden, O.M.; et al. Predictive Factors for Hypertrophy of the Future Liver Remnant After Portal Vein Embolization: A Systematic Review. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2021, 44, 1355–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasselgren, K.; Malagò, M.; Vyas, S.; Campos, R.R.; Brusadin, R.; Linecker, M.; Petrowsky, H.; Clavien, P.A.; Machado, M.A.; Hernandez-Alejandro, R.; et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Does Not Affect Future Liver Remnant Growth and Outcomes of Associating Liver Partition and Portal Vein Ligation for Staged Hepatectomy. Surgery 2017, 161, 1255–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorzi, D.; Chun, Y.S.; Madoff, D.C.; Abdalla, E.K.; Vauthey, J.-N. Chemotherapy with Bevacizumab Does Not Affect Liver Regeneration after Portal Vein Embolization in the Treatment of Colorectal Liver Metastases. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2008, 15, 2765–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simoneau, E.; Alanazi, R.; Alshenaifi, J.; Molla, N.; Aljiffry, M.; Medkhali, A.; Boucher, L.-M.; Asselah, J.; Metrakos, P.; Hassanain, M. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Does Not Impair Liver Regeneration Following Hepatectomy or Portal Vein Embolization for Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastases. J. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 113, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goéré, D.; Farges, O.; Leporrier, J.; Sauvanet, A.; Vilgrain, V.; Belghiti, J. Chemotherapy Does Not Impair Hypertrophy of the Left Liver after Right Portal Vein Obstruction. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2006, 10, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, X.; Korenblik, R.; Olij, B.; Knapen, R.R.M.M.; van der Leij, C.; Heise, D.; den Dulk, M.; Neumann, U.P.; Schaap, F.G.; van Dam, R.M.; et al. Influence of Cholestasis on Portal Vein Embolization-Induced Hypertrophy of the Future Liver Remnant. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2023, 408, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizuno, S.; Nimura, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Yoshida, S. Portal Vein Branch Occlusion Induces Cell Proliferation of Cholestatic Rat Liver. J. Surg. Res. 1996, 60, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanashima, A.; Sumida, Y.; Shibasaki, S.; Takeshita, H.; Hidaka, S.; Sawai, T.; Shindou, H.; Abo, T.; Yasutake, T.; Nagayasu, T.; et al. Parameters Associated with Changes in Liver Volume in Patients Undergoing Portal Vein Embolization. J. Surg. Res. 2006, 133, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roy, B.; Dupré, A.; Gallon, A.; Chabrot, P.; Gagnière, J.; Buc, E. Liver hypertrophy: Underlying mechanisms and promoting procedures before major hepatectomy. J. Visc. Surg. 2018, 155, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | PVE (26) | LVD (10) | eLVD (8) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age: mean in years (SD) | 65.6 (9.5) | 59.9 (9.9) | 63.1 (7.3) | 0.25 |

| Sex | 0.06 | |||

| Female | 12 (46%) | 3 (30%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Male | 14 (54%) | 7 (70%) | 8 (100%) | |

| Type of cancer | 0.45 | |||

| HCC | 6 (23%) | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) | |

| CCK | 7 (27%) | 2 (20%) | 1 (12%) | |

| CRLM | 13 (50%) | 7 (70%) | 7 (88%) | |

| Preoperative chemotherapy | 0.03 | |||

| No | 15 (57%) | 2 (20%) | 1 (12%) | |

| Yes | 11 (43%) | 8 (80%) | 7 (88%) | |

| Preoperative TACE | 0.46 | |||

| No | 22 (84%) | 10 (100%) | 8 (100%) | |

| Yes | 4 (16%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Mean FRL volume (SD) | 30% (7) | 29% (5) | 27% (7) | 0.55 |

| Median number of nodules (IQR) | 1 (1) | 2.5 (4) | 3.5 (1.5) | 0.03 |

| Median sum of nodules diameters (IQR) | 65 (68) | 51.5 (23) | 53 (57.5) | 0.83 |

| Variable | PVE (n = 26) | LVD (n = 10) | eLVD (n = 8) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VG—segment 1 (SD) | 8.5 (13) | 11 (19) | 28.5 (14) | <0.01 |

| VG—segments 2+3 (SD) | 104 (115) | 112 (25) | 208 (82) | 0.01 |

| VG—segment 4 (SD) | 31 (52) | 34 (50) | 53 (58) | 0.84 |

| VG—FRL (SD) | 154 (158) | 162 (188) | 273 (168) | 0.01 |

| VGR—embolized liver (SD) | −132 (271) | −72 (295) | −60 (267) | 0.93 |

| Variable | PVE (n = 26) | LVD (n = 10) | eLVD (n = 8) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume gain—segment 1 (SD) | 27.3 (35.4) | 38.7 (13.5) | 79.1 (41.2) | <0.01 |

| Volume gain—segments 2+3 (SD) | 40.7 (40.5) | 45.0 (21.5) | 85.4 (45.5) | 0.01 |

| Volume gain—segment 4 (SD) | 16.5 (28.4) | 17.5 (30.9) | 22.6 (41.9) | 0.79 |

| Volume gain—FRL (SD) | 28.1 (28.3) | 33.5 (21.2) | 68.6 (42.0) | 0.03 |

| Variable | PVE (26) | LVD (10) | eLVD (8) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KGR—segment 1 (SD) | 0.11 (0.11) | 0.17 (0.15) | 0.27 (0.24) | <0.01 |

| KGR—segments 2+3 (SD) | 1.72 (1.72) | 1.89 (1.21) | 2.89 (1.53) | 0.13 |

| KGR—segment 4 (SD) | 0.48 (1.07) | 0.34 (1.04) | 0.23 (0.90) | 0.94 |

| KGR—FRL (SD) | 2.22 (2.11) | 2.43 (3.78) | 3.21 (1.37) | 0.28 |

| KGR—embolized liver (SD) | −2.22 (2.11) | −2.43 (3.78) | −3.21 (1.37) | 0.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al Taweel, B.; Cassese, G.; Khayat, S.; Chazal, M.; Navarro, F.; Guiu, B.; Panaro, F. Assessment of Segmentary Hypertrophy of Future Remnant Liver after Liver Venous Deprivation: A Single-Center Study. Cancers 2024, 16, 1982. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16111982

Al Taweel B, Cassese G, Khayat S, Chazal M, Navarro F, Guiu B, Panaro F. Assessment of Segmentary Hypertrophy of Future Remnant Liver after Liver Venous Deprivation: A Single-Center Study. Cancers. 2024; 16(11):1982. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16111982

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl Taweel, Bader, Gianluca Cassese, Salah Khayat, Maurice Chazal, Francis Navarro, Boris Guiu, and Fabrizio Panaro. 2024. "Assessment of Segmentary Hypertrophy of Future Remnant Liver after Liver Venous Deprivation: A Single-Center Study" Cancers 16, no. 11: 1982. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16111982

APA StyleAl Taweel, B., Cassese, G., Khayat, S., Chazal, M., Navarro, F., Guiu, B., & Panaro, F. (2024). Assessment of Segmentary Hypertrophy of Future Remnant Liver after Liver Venous Deprivation: A Single-Center Study. Cancers, 16(11), 1982. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16111982