Impact of Real-World Outpatient Cancer Rehabilitation Services on Health-Related Quality of Life of Cancer Survivors across 12 Diagnosis Types in the United States

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Identification and Data Extraction

2.2. PROMIS Measures and Scoring

2.3. Covariates

2.4. Statistical Analysis

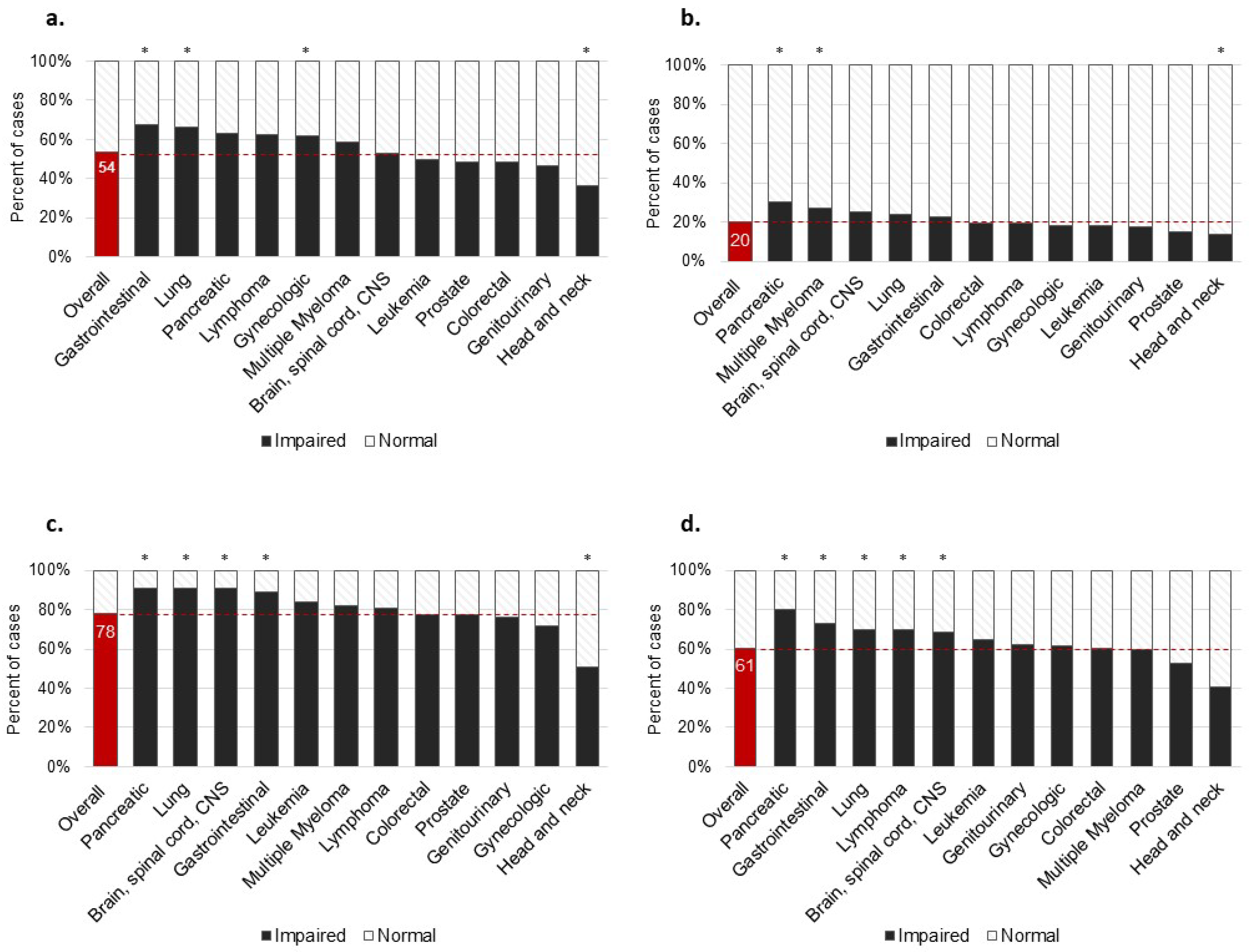

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical and Public Health Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cespedes Feliciano, E.M.; Vasan, S.; Luo, J.; Binder, A.M.; Rowan, S.; Chlebowski, T.; Quesenberry, C.; Banack, H.R.; Caan, B.J.; Paskett, E.D.; et al. Long-term Trajectories of Physical Function Decline in Women with and without Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, K.E.; Forsythe, L.P.; Reeve, B.B.; Alfano, C.M.; Rodriguez, J.L.; Sabatino, S.A.; Hawkins, N.A.; Rowland, J.H. Mental and physical health-related quality of life among U.S. cancer survivors: Population estimates from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2012, 21, 2108–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Jimenez, A.; Cantarero-Villanueva, I.; Delgado-Garcia, G.; Molina-Barea, R.; Fernandez-Lao, C.; Galiano-Castillo, N.; Arroyo-Morales, M. Physical impairments and quality of life of colorectal cancer survivors: A case-control study. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2015, 24, 642–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoelstra, S.L.; Given, B.A.; Schutte, D.L.; Sikorskii, A.; You, M.; Given, C.W. Do Older Adults with Cancer Fall More Often? A Comparative Analysis of Falls in Those with and without Cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2013, 40, E69–E78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, N.; Coxon, H.; Nabarro, S.; Hardy, B.; Cox, K. Unmet care needs in people living with advanced cancer: A systematic review. Support Care Cancer 2016, 24, 3609–3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reb, A.M.; Cope, D.G. Quality of Life and Supportive Care Needs of Gynecologic Cancer Survivors. West J. Nurs. Res. 2019, 41, 1385–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergolotti, M.; Bailliard, A.; McCarthy, L.; Farley, E.; Covington, K.R.; Doll, K.M. Women’s Experiences After Ovarian Cancer Surgery: Distress, Uncertainty, and the Need for Occupational Therapy. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 74, 7403205140p1–7403205140p9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, J.V.T.; Matusko, N.; Hendren, S.; Regenbogen, S.E.; Hardiman, K.M. Patient-Reported Unmet Needs in Colorectal Cancer Survivors After Treatment for Curative-Intent. Dis. Colon Rectum 2019, 62, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, C.; Robertson, A.; Smith, A.; Nabi, G. Identifying the unmet supportive care needs of men living with and beyond prostate cancer: A systematic review. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2015, 19, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringash, J.; Bernstein, L.J.; Devins, G.; Dunphy, C.; Giuliani, M.; Martino, R.; McEwen, S. Head and Neck Cancer Survivorship: Learning the Needs, Meeting the Needs. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 2018, 28, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayly, J.L.; Lloyd-Williams, M. Identifying functional impairment and rehabilitation needs in patients newly diagnosed with inoperable lung cancer: A structured literature review. Support Care Cancer 2016, 24, 2359–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitlinger, A.; Zafar, S.Y. Health-Related Quality of Life: The Impact on Morbidity and Mortality. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 27, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitlinger, A.; Shelby, R.A.; Van Denburg, A.N.; White, H.; Edmond, S.N.; Marcom, P.K.; Bosworth, H.B.; Keefe, F.J.; Kimmick, G.G. Higher symptom burden is associated with lower function in women taking adjuvant endocrine therapy for breast cancer. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2019, 10, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efficace, F.; Bottomley, A.; Coens, C.; Van Steen, K.; Conroy, T.; Schöffski, P.; Schmoll, H.; Van Cutsem, E.; Köhne, C.H. Does a patient’s self-reported health-related quality of life predict survival beyond key biomedical data in advanced colorectal cancer? Eur. J. Cancer 2006, 42, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, C.M.; Vistisen, K.K.; Dehlendorff, C.; Ronholt, F.; Johansen, J.S.; Nielsen, D.L. The effect of geriatric intervention in frail older patients receiving chemotherapy for colorectal cancer: A randomised trial (GERICO). Clin. Study Br. J. Cancer 2021, 124, 1949–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clough-Gorr, K.M.; Stuck, A.E.; Thwin, S.S.; Silliman, R.A. Older Breast Cancer Survivors: Geriatric Assessment Domains Are Associated with Poor Tolerance of Treatment Adverse Effects and Predict Mortality Over 7 Years of Follow-Up. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannes, T.S.; Simoneau, T.L.; Mikulich-Gilbertson, S.K.; Natvig, C.L.; Brewer, B.W.; Kilbourn, K.; Laudenslager, M.L. Distress and quality of life in patient and caregiver dyads facing stem cell transplant: Identifying overlap and unique contributions. Support Care Cancer 2019, 27, 2329–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-S.; Harden, J.K. Symptom Burden and Quality of Life in Survivorship. Cancer Nurs. 2015, 38, E29–E54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.R.; Dunham, L.; Chang, Y.K.; Deal, A.M.; Pergolotti, M.; Lund, J.L.; Guerard, E.; Kenzik, K.; Muss, H.B.; Sanoff, H.K. Geriatric Assessment Predicts Hospitalization Frequency and Long-Term Care Use in Older Adult Cancer Survivors. J. Oncol. Pract. 2019, 15, E399–E409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluethmann, S.M.; Mariotto, A.B.; Rowland, J.H. Anticipating the “Silver Tsunami”: Prevalence Trajectories and Comorbidity Burden among Older Cancer Survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2016, 25, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfano, C.M.; Leach, C.R.; Smith, T.G.; Miller, K.D.; Alcaraz, K.I.; Cannady, R.S.; Wender, R.C.; Brawley, O.W. Equitably improving outcomes for cancer survivors and supporting caregivers: A blueprint for care delivery, research, education, and policy. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levit, L.A.; Balogh, E.P.; Nass, S.J.; Ganz, P.A. (Eds.) Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergolotti, M.; Alfano, C.M.; Cernich, A.N.; Yabroff, K.R.; Manning, P.R.; de Moor, J.S.; Hahn, E.E.; Cheville, A.L.; Mohile, S.G. A health services research agenda to fully integrate cancer rehabilitation into oncology care. Cancer 2019, 125, 3908–3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfano, C.M.; Pergolotti, M. Next-Generation Cancer Rehabilitation: A Giant Step Forward for Patient Care. Rehabil. Nurs. 2018, 43, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brick, R.; Padgett, L.; Jones, J.; Wood, K.C.; Pergolotti, M.; Marshall, T.F.; Campbell, G.; Eilers, R.; Keshavarzi, S.; Flores, A.M.; et al. The influence of telehealth-based cancer rehabilitation interventions on disability: A systematic review. J. Cancer Surviv. 2022, 17, 1725–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleight, A.; Gerber, L.H.; Marshall, T.F.; Livinski, A.; Alfano, C.M.; Harrington, S.; Flores, A.M.; Virani, A.; Hu, X.; Mitchell, S.A.; et al. Systematic Review of Functional Outcomes in Cancer Rehabilitation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 103, 1807–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, E.G.; Gibson, R.W.; Arbesman, M.; D’Amico, M. Systematic Review of Occupational Therapy and Adult Cancer Rehabilitation: Part 1. Impact of Physical Activity and Symptom Management Interventions. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2017, 71, 7102100030p1–7102100030p11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, E.G.; Gibson, R.W.; Arbesman, M.; D’Amico, M. Systematic Review of Occupational Therapy and Adult Cancer Rehabilitation: Part 2. Impact of Multidisciplinary Rehabilitation and Psychosocial, Sexuality, and Return-to-Work Interventions. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2017, 71, 7102100040p1–7102100040p8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longacre, C.F.; Nyman, J.A.; Visscher, S.L.; Borah, B.J.; Cheville, A.L. Cost-effectiveness of the Collaborative Care to Preserve Performance in Cancer (COPE) trial tele-rehabilitation interventions for patients with advanced cancers. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 2723–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mewes, J.C.; Steuten, L.M.G.; IJzerman, M.J.; van Harten, W.H. Effectiveness of Multidimensional Cancer Survivor Rehabilitation and Cost-Effectiveness of Cancer Rehabilitation in General: A Systematic Review. Oncologist 2012, 17, 1581–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, J.; Mazuquin, B.; Canaway, A.; Hossain, A.; Williamson, E.; Mistry, P.; Lall, R.; Petrou, S.; Lamb, S.E.; Rees, S.; et al. Exercise versus usual care after non-reconstructive breast cancer surgery (UK PROSPER): Multicentre randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation. BMJ 2021, 375, e066542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergolotti, M.; Deal, A.M.; Williams, G.R.; Bryant, A.L.; McCarthy, L.; Nyrop, K.A.; Covington, K.R.; Reeve, B.B.; Basch, E.; Muss, H.B. Older Adults with Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Occupational and Physical Therapy. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 953–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brick, R.; Lyons, K.D.; Bender, C.; Eilers, R.; Ferguson, R.; Pergolotti, M.; Toto, P.; Skidmore, E.; Leland, N.E. Factors influencing utilization of cancer rehabilitation services among older breast cancer survivors in the USA: A qualitative study. Support Care Cancer 2022, 30, 2397–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergolotti, M.; Wood, K.C.; Kendig, T. The broader impact of specialized outpatient cancer rehabilitation on health and quality of life among breast cancer survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41 (Suppl. 16), e18881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motheral, B.; Brooks, J.; Clark, M.A.; Crown, W.H.; Davey, P.; Hutchins, D.; Martin, B.C.; Stang, P. A Checklist for Retrospective Database Studies—Report of the ISPOR Task Force on Retrospective Databases. Value Health 2003, 6, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ader, D.N. Developing the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Med. Care 2007, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, D.; Riley, W.; Stone, A.; Rothrock, N.; Reeve, B.; Yount, S.; Amtmann, D.; Bode, R.; Buysse, D.; Choi, S.; et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2010, 63, 1179–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, B.B.; Hays, R.D.; Bjorner, J.B.; Cook, K.; Crane, P.K.; Teresi, J.A.; Thissen, D.; Revicki, D.A.; Weiss, D.J.; Hambleton, H.L.; et al. Psychometric Evaluation and Calibration of Health-Related Quality of Life Item Banks: Plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Med. Care 2007, 45, S22–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalet, B.D.; Hays, R.D.; Jensen, S.E.; Beaumont, J.L.; Fries, J.F.; Cella, D. Validity of PROMIS physical function measured in diverse clinical samples. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 73, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, R.D.; Spritzer, K.L.; Thompson, W.W.; Cella, D.U.S. General Population Estimate for “Excellent” to “Poor” Self-Rated Health Item. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015, 30, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, R.E.; Moinpour, C.M.; Potosky, A.L.; Lobo, T.; Hahn, E.A.; Hays, R.D.; Cella, D.; Smith, A.W.; Wu, X.C.; Keegan, T.H.M.; et al. Responsiveness of 8 PROMIS® Measures in a Large, Community-Based Cancer Study Cohort. Cancer 2017, 123, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terwee, C.B.; Peipert, J.D.; Chapman, R.; Lai, J.S.; Terluin, B.; Cella, D.; Griffith, P.; Mokkink, L.B. Minimal important change (MIC): A conceptual clarification and systematic review of MIC estimates of PROMIS measures. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 2729–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, B.E.; Syrjala, K.L.; Onstad, L.E.; Chow, E.J.; Flowers, M.E.; Jim, H.; Baker, K.S.; Buckley, S.; Fairclough, D.L.; Horowitz, M.M.; et al. PROMIS measures can be used to assess symptoms and function in long-term hematopoietic cell transplantation survivors. Cancer 2018, 124, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneviratne, M.G.; Bozkurt, S.; Patel, M.I.; Seto, T.; Brooks, J.D.; Blayney, D.W.; Kurian, A.W.; Hernandez-Boussard, T. Distribution of global health measures from routinely collected PROMIS surveys in patients with breast cancer or prostate cancer. Cancer 2019, 125, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gressel, G.M.; Dioun, S.M.; Richley, M.; Lounsbury, D.W.; Rapkin, B.D.; Isani, S.; Nevadunsky, N.S.; Kuo, D.Y.S.; Novetsky, A.P. Utilizing the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) to increase referral to ancillary support services for severely symptomatic patients with gynecologic cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2019, 152, 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Y.W.; Brown, C.; Cosio, A.P.; Dobriyal, A.; Malik, N.; Pat, V.; Irwin, M.; Tomasini, P.; Liu, G.; Howell, D. Feasibility and diagnostic accuracy of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) item banks for routine surveillance of sleep and fatigue problems in ambulatory cancer care. Cancer 2016, 122, 2906–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, L.I.; Schink, J.; Bass, M.; Patel, S.; Diaz, M.V.; Rothrock, N.; Pearman, T.; Gershon, R.; Penedo, F.J.; Rosen, S.; et al. Bringing PROMIS to practice: Brief and precise symptom screening in ambulatory cancer care. Cance 2015, 121, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, R.D.; Bjorner, J.B.; Revicki, D.A.; Spritzer, K.L.; Cella, D. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual. Life Res. 2009, 18, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2021. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 4/10/2023).

- Wood, K.C.; Bertram, J.J.; Kendig, T.D.; Pergolotti, M. Understanding Patient Experience with Outpatient Cancer Rehabilitation Care. Healthcare 2023, 11, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, K.C.; Hidde, M.; Kendig, T.; Pergolotti, M. Community-based outpatient rehabilitation for the treatment of breast cancer-related upper extremity disability: An evaluation of practice-based evidence. Breast Cancer 2022, 29, 1099–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, K.C.; Bertram, J.; Kendig, T.; Hidde, M.; Leiser, A.; Buckley de Meritens, A.; Pergolotti, M. Community-based outpatient cancer rehabilitation services for women with gynecologic cancer: Acceptability and impact on patient-reported outcomes. Support Care Cancer 2022, 30, 8089–8099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergolotti, M.; Covington, K.R.; Lightner, A.N.; Bertram, J.; Thess, M.; Sharp, J.; Spraker, M.; Williams, G.R.; Manning, P. Association of Outpatient Cancer Rehabilitation with Patient-Reported Outcomes and Performance-Based Measures of Function. Rehabil. Oncol. 2021, 39, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergolotti, M.; Deal, A.M.; Lavery, J.; Reeve, B.B.; Muss, H.B. The prevalence of potentially modifiable functional deficits and the subsequent use of occupational and physical therapy by older adults with cancer. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2015, 6, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brick, R.; Natori, A.; Moreno, P.I.; Molinares, D.; Koru-Sengul, T.; Penedo, F.J. Predictors of cancer rehabilitation medicine referral and utilization based on the Moving Through Cancer physical activity screening assessment. Support Care Cancer 2023, 31, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Obaidi, M.; Giri, S.; Mir, N.; Kenzik, K.; McDonald, A.M.; Smith, C.Y.; Gbolahan, O.B.; Paluri, R.K.; Bhatia, S.; Williams, G.R. Use of self-rated health to identify frailty and predict mortality in older adults with cancer. Results from the care study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38 (Suppl. S15), 12046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, C.R.; Gapstur, S.M.; Cella, D.; Deubler, E.; Teras, L.R. Age-related health deficits and five-year mortality among older, long-term cancer survivors. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2022, 13, 1023–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal, J.W.; Roy, M.; Bugos, K.; Sharp, C.; Galatin, P.S.; Falconer, P.; Rosenthal, E.L.; Blayney, D.W.; Modaressi, S.; Robinson, A.; et al. Distress Screening Through Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) at an Academic Cancer Center and Network Site: Implementation of a Hybrid Model. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2021, 17, e1688–e1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, L.E.; Zelinski, E.L.; Toivonen, K.I.; Sundstrom, L.; Jobin, C.T.; Damaskos, P.; Zebrack, B. Prevalence of psychosocial distress in cancer patients across 55 North American cancer centers. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2019, 37, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firkins, J.; Hansen, L.; Driessnack, M.; Dieckmann, N. Quality of life in “chronic” cancer survivors: A meta-analysis. J. Cancer Surviv. 2020, 14, 504–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, J.M.; Stella, P.J.; LaVasseur, B.; Adams, P.T.; Swafford, L.; Lewis, J.; Mendelsohn-Victor, K.; Friese, C.R. Toxicity-Related Factors Associated with Use of Services Among Community Oncology Patients. J. Oncol. Pract. 2016, 12, e818–e827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.M.; Ream, M.E.; Pensak, N.; Nisotel, L.E.; Fishbein, J.N.; MacDonald, J.J.; Buzaglo, J.; Lennes, I.T.; Safren, S.A.; Pirl, W.F.; et al. Patient Experiences with Oral Chemotherapy: Adherence, Symptoms, and Quality of Life. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2019, 17, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkhus, L.; Harneshaug, M.; Saltyte Benth, J.; Gronberg, B.H.; Rostoft, S.; Bergh, S.; Hjermstad, M.J.; Selbaek, G.; Wyller, T.B.; Kirkevold, O.; et al. Modifiable factors affecting older patients’ quality of life and physical function during cancer treatment. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2019, 10, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duma, N.; Aguilera, J.V.; Paludo, J.; Haddox, C.L.; Velez, M.G.; Wang, Y.; Leventakos, K.; Hubbard, J.M.; Mansfield, A.S.; Go, R.S.; et al. Representation of Minorities and Women in Oncology Clinical Trials: Review of the Past 14 Years. J. Oncol. Pract. 2018, 14, e1–e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthy, V.H.; Krumholz, H.M.; Gross, C.P. Participation in Cancer Clinical Trials: Race-, Sex-, and Age-Based Disparities. JAMA 2004, 291, 2720–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penberthy, L.T.; Rivera, D.R.; Lund, J.L.; Bruno, M.A.; Meyer, A.-M. An overview of real-world data sources for oncology and considerations for research. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licht, T.; Nickels, A.; Rumpold, G.; Holzner, B.; Riedl, D. Evaluation by electronic patient-reported outcomes of cancer survivors’ needs and the efficacy of inpatient cancer rehabilitation in different tumor entities. Support Care Cancer 2021, 29, 5853–5864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riedl, D.; Giesinger, J.M.; Wintner, L.M.; Loth, F.L.; Rumpold, G.; Greil, R.; Nickels, A.; Licht, T.; Holzner, B. Improvement of quality of life and psychological distress after inpatient cancer rehabilitation: Results of a longitudinal observational study. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2017, 129, 692–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faller, H.; Hass, H.G.; Engehausen, D.; Reuss-Borst, M.; Wöckel, A. Supportive care needs and quality of life in patients with breast and gynecological cancer attending inpatient rehabilitation. A prospective study. Acta Oncol. 2019, 58, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tennison, J.M.; Rianon, N.J.; Manzano, J.G.; Munsell, M.F.; George, M.C.; Bruera, E. Thirty-day hospital readmission rate, reasons, and risk factors after acute inpatient cancer rehabilitation. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 6199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergolotti, M.; Williams, G.R.; Campbell, C.; Munoz, L.A.; Muss, H.B. Occupational Therapy for Adults with Cancer: Why It Matters. Oncologist 2016, 21, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Mean ± SD, N, % |

|---|---|

| Age (Mean ± SD, range) | 65.45 ± 12.84, 19.0–91.0 |

| Sex (n, %) | |

| Female | 650, 45.9% |

| Male | 765, 54.1% |

| Race/ethnicity (n, %) a | |

| White | 538, 80.7% |

| Black/African American | 63, 9.4% |

| Hispanic | 38, 5.7% |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 27, 4.1% |

| United States region | |

| South | 585, 39.8% |

| Northeast | 385, 26.2% |

| Southeast | 241, 16.4% |

| Midwest | 177, 12.0% |

| West | 82, 5.6% |

| Insurer type | |

| Federally funded | 879, 62.1% |

| Private or self-pay | 536, 37.89% |

| Cancer type | |

| Head and neck | 257, 18.2% |

| Lung | 169, 11.9% |

| Gynecologic | 158, 11.2% |

| Prostate | 146, 10.3% |

| Colorectal | 118, 8.3% |

| Multiple Myeloma | 111, 7.6% |

| Lymphoma | 98, 6.9% |

| Gastrointestinal | 83, 5.9% |

| Genitourinary | 75, 5.3% |

| Pancreatic | 70, 4.9% |

| Leukemia | 66, 4.7% |

| Brain, spinal cord, nervous system | 64, 4.5% |

| Rehabilitation service type (N, %) | |

| PT | 1314, 92.9% |

| OT | 101, 7.1% |

| Visits completed (Median, IQR) | 12.00, 8.00–19.00 |

| Length of care, weeks (Median, IQR) | 28.00, 9.14–80.00 |

| N | Initial Evaluation EM Mean, SE | Discharge EM Mean, SE | EM Mean Change, SE | p-Value | Achieved MIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head and neck | 257 | 44.45, 0.526 | 48.41, 0.526 | 3.96, 0.471 † | <0.001 ** | 61.9% |

| Lung | 169 | 39.04, 0.598 | 43.02, 0.598 | 3.97, 0.596 † | <0.001 ** | 63.9% |

| Gynecologic | 158 | 39.54, 0.526 | 43.90, 0.526 | 4.36, 0.489 † | <0.001 ** | 67.7% |

| Prostate | 146 | 41.64, 0.667 | 44.88, 0.667 | 3.24, 0.503 † | <0.001 ** | 60.3% |

| Colorectal | 118 | 42.07, 0.728 | 45.00, 0.728 | 2.93, 0.587 † | <0.001 ** | 61.9% |

| Multiple Myeloma | 111 | 39.18, 0.739 | 42.58, 0.739 | 3.40, 0.601 † | 0.001 ** | 64.0% |

| Lymphoma | 98 | 39.77, 0.831 | 43.67, 0.831 | 3.89, 0.645 † | <0.001 ** | 65.3% |

| Gastrointestinal | 83 | 39.14, 0.810 | 42.51, 0.810 | 3.37, 0.850 † | <0.001 ** | 65.1% |

| Genitourinary | 75 | 42.08, 1.04 | 45.21, 1.04 | 3.13, 0.872 † | 0.001 ** | 49.3% |

| Pancreatic | 70 | 38.81, 0.778 | 41.88, 0.778 | 3.07, 0.777 † | <0.001 ** | 61.4% |

| Leukemia | 66 | 40.25, 0.958 | 45.39, 0.958 | 5.15, 0.810 † | <0.001 ** | 71.2% |

| Brain, spinal cord, nervous system | 64 | 40.74, 0.967 | 44.90, 0.967 | 4.16, 1.02 † | <0.001 ** | 68.8% |

| N | Initial Evaluation EM Mean, SE | Discharge EM Mean, SE | EM Mean Change, SE | p-Value | Achieved MIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head and neck | 257 | 48.93, 0.563 | 51.02, 0.563 | 1.92, 1.12 | <0.001 ** | 52.1% |

| Lung | 169 | 45.67, 0.650 | 48.59, 0.650 | 1.83, 0.580 | <0.001 ** | 55% |

| Gynecologic | 158 | 46.42, 0.647 | 48.82, 0.647 | 2.20, 0.850 † | <0.001 ** | 51.9% |

| Prostate | 146 | 48.54, 0.716 | 50.35, 0.716 | 1.83, 0.883 | 0.002 ** | 56.8% |

| Colorectal | 118 | 47.45, 0.801 | 49.28, 0.801 | 2.40, 0.550 † | 0.002 * | 46.6% |

| Multiple Myeloma | 111 | 45.80, 0.770 | 47.88, 0.770 | 2.09, 0.497 † | 0.001 ** | 56.8% |

| Lymphoma | 98 | 46.94, 0.954 | 48.88, 0.954 | 2.72, 0.722 † | 0.005 ** | 53.1% |

| Gastrointestinal | 83 | 45.82, 0.938 | 47.66, 0.938 | 2.93, 0.584 † | <0.001 ** | 50.6% |

| Genitourinary | 75 | 48.75, 0.996 | 50.94, 0.996 | 1.94, 0.683 | 0.012 * | 57.3% |

| Pancreatic | 70 | 44.76, 1.00 | 46.91, 1.00 | 2.07, 0.643 † | 0.020 * | 48.6% |

| Leukemia | 66 | 47.71, 1.04 | 50.43, 1.04 | 2.15, 0.901 † | <0.001 ** | 63.6% |

| Brain, spinal cord, nervous system | 64 | 46.25, 1.09 | 48.17, 1.09 | 3.24, 0.503 † | 0.091 | 51.6% |

| N | Initial Evaluation EM Mean, SE | Discharge EM Mean, SE | EM Mean Change, SE | p-Value | Achieved MIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head and neck | 257 | 44.22, 0.579 | 46.88, 0.579 | 2.66, 0.465 † | <0.001 ** | 45.0% |

| Lung | 169 | 35.20, 0.625 | 39.13, 0.625 | 3.93, 0.601 † | <0.001 ** | 53.9% |

| Gynecologic | 158 | 37.84, 0.656 | 41.44, 0.656 | 4.36, 0.489 † | <0.001 ** | 55.9% |

| Prostate | 146 | 39.52, 0.711 | 41.89, 0.711 | 2.37, 0.521 † | <0.001 ** | 43.4% |

| Colorectal | 118 | 39.53, 0.808 | 42.37, 0.808 | 2.84, 0.550 † | <0.001 ** | 51.4% |

| Multiple Myeloma | 111 | 37.96, 0.841 | 40.75, 0.841 | 2.78, 0.674 † | <0.001 ** | 49.5% |

| Lymphoma | 98 | 38.04, 0.776 | 41.11, 0.776 | 3.07, 0.755 † | <0.001 ** | 50.0% |

| Gastrointestinal | 83 | 36.66, 0.830 | 39.45, 0.830 | 2.79, 0.733 † | <0.001 ** | 47.9% |

| Genitourinary | 75 | 39.23, 1.07 | 42.19, 1.07 | 2.97, 0.883 † | 0.001 ** | 46.5% |

| Pancreatic | 70 | 36.74, 0.893 | 40.00, 0.893 | 3.26, 0.827 † | <0.001 ** | 51.5% |

| Leukemia | 66 | 36.97, 1.03 | 41.59, 1.03 | 4.61, 0.855 † | <0.001 ** | 67.2% |

| Brain, spinal cord, nervous system | 64 | 35.53, 0.967 | 38.92, 0.967 | 3.39, 0.960 † | 0.001 ** | 56.6% |

| N | Initial Evaluation EM Mean, SE | Discharge EM Mean, SE | EM Mean Change, SE | p-Value | Achieved MIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head and neck | 257 | 49.98, 0.628 | 52.50, 0.628 | 2.52, 0.625 † | <0.001 ** | 45.1% |

| Lung | 169 | 43.24, 0.680 | 47.21, 0.680 | 3.97, 0.670 † | <0.001 ** | 55.9% |

| Gynecologic | 158 | 44.84, 0.718 | 47.87, 0.718 | 3.03, 0.711 † | <0.001 ** | 53.0% |

| Prostate | 146 | 47.00, 0.791 | 49.16, 0.791 | 2.16, 0.686 † | 00.002 ** | 40.8% |

| Colorectal | 118 | 45.72, 0.822 | 48.88, 0.822 | 3.16, 0.695 † | <0.001 ** | 49.1% |

| Multiple Myeloma | 111 | 43.77, 0.817 | 47.23, 0.817 | 3.46, 0.766 † | <0.001 ** | 48.4% |

| Lymphoma | 98 | 45.05, 0.945 | 48.26, 0.945 | 3.21, 0.886 † | <0.001 ** | 52.2% |

| Gastrointestinal | 83 | 43.40, 1.03 | 47.30, 1.03 | 3.90, 0.850 † | 0.001 ** | 57.1% |

| Genitourinary | 75 | 45.19, 1.08 | 48.78, 1.08 | 3.59, 0.992 † | 0.001 ** | 47.8% |

| Pancreatic | 70 | 42.08, 0.846 | 46.38, 0.846 | 4.31, 0.802 † | <0.001 ** | 57.6% |

| Leukemia | 66 | 45.12, 1.18 | 50.65, 1.18 | 5.53, 1.02 † | <0.001 ** | 64.5% |

| Brain, spinal cord, nervous system | 64 | 42.84, 1.23 | 46.73, 1.23 | 4.16, 1.02 † | 0.003 ** | 48.1% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pergolotti, M.; Wood, K.C.; Kendig, T.D.; Mayo, S. Impact of Real-World Outpatient Cancer Rehabilitation Services on Health-Related Quality of Life of Cancer Survivors across 12 Diagnosis Types in the United States. Cancers 2024, 16, 1927. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16101927

Pergolotti M, Wood KC, Kendig TD, Mayo S. Impact of Real-World Outpatient Cancer Rehabilitation Services on Health-Related Quality of Life of Cancer Survivors across 12 Diagnosis Types in the United States. Cancers. 2024; 16(10):1927. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16101927

Chicago/Turabian StylePergolotti, Mackenzi, Kelley C. Wood, Tiffany D. Kendig, and Stacye Mayo. 2024. "Impact of Real-World Outpatient Cancer Rehabilitation Services on Health-Related Quality of Life of Cancer Survivors across 12 Diagnosis Types in the United States" Cancers 16, no. 10: 1927. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16101927

APA StylePergolotti, M., Wood, K. C., Kendig, T. D., & Mayo, S. (2024). Impact of Real-World Outpatient Cancer Rehabilitation Services on Health-Related Quality of Life of Cancer Survivors across 12 Diagnosis Types in the United States. Cancers, 16(10), 1927. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16101927