End-of-Life Symptom Burden among Patients with Cancer Who Were Provided Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID): A Longitudinal Propensity-Score-Matched Cohort Study

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

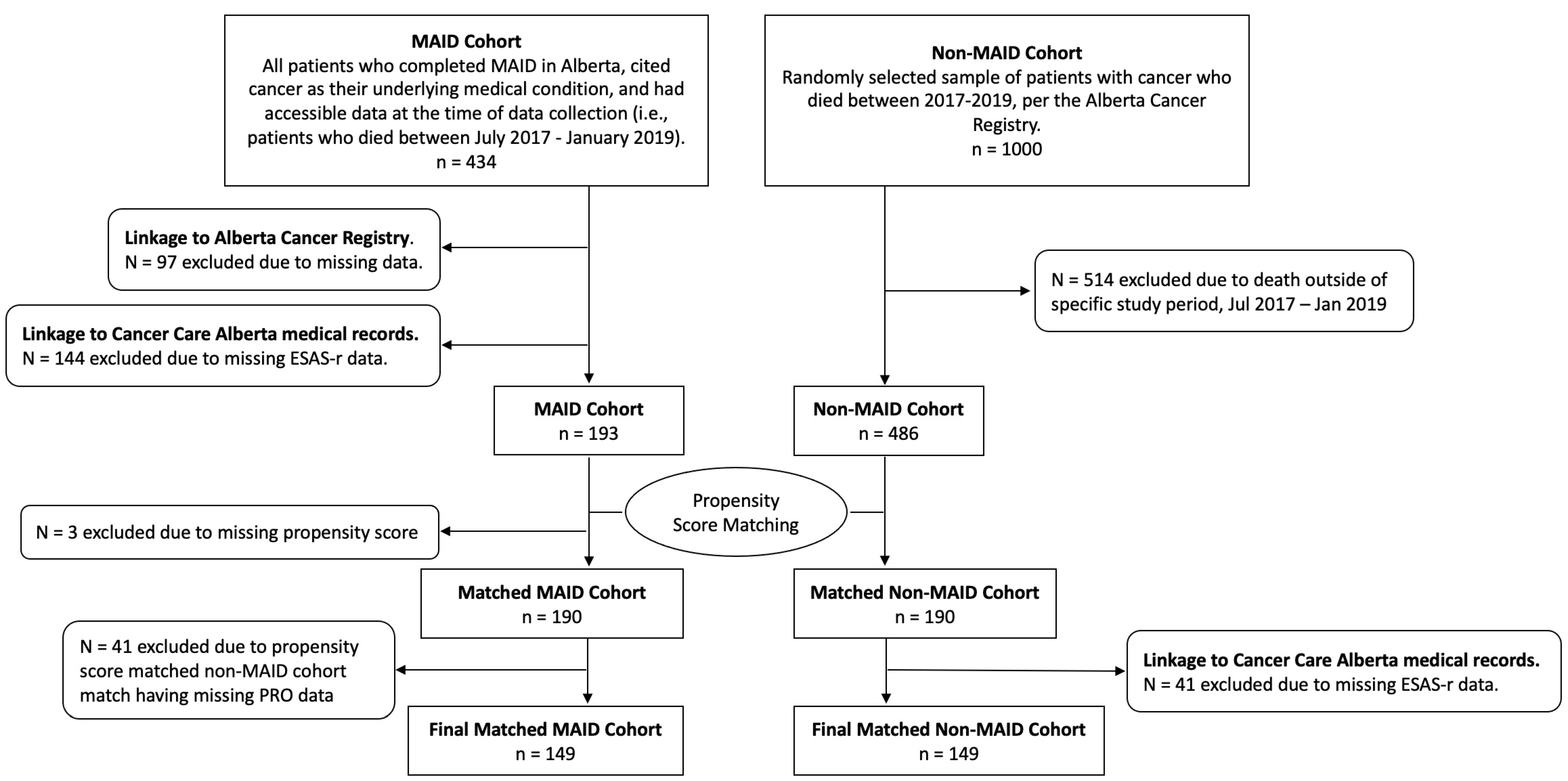

2.2. Propensity Score Matching

2.3. Study Sample

2.4. Measures

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

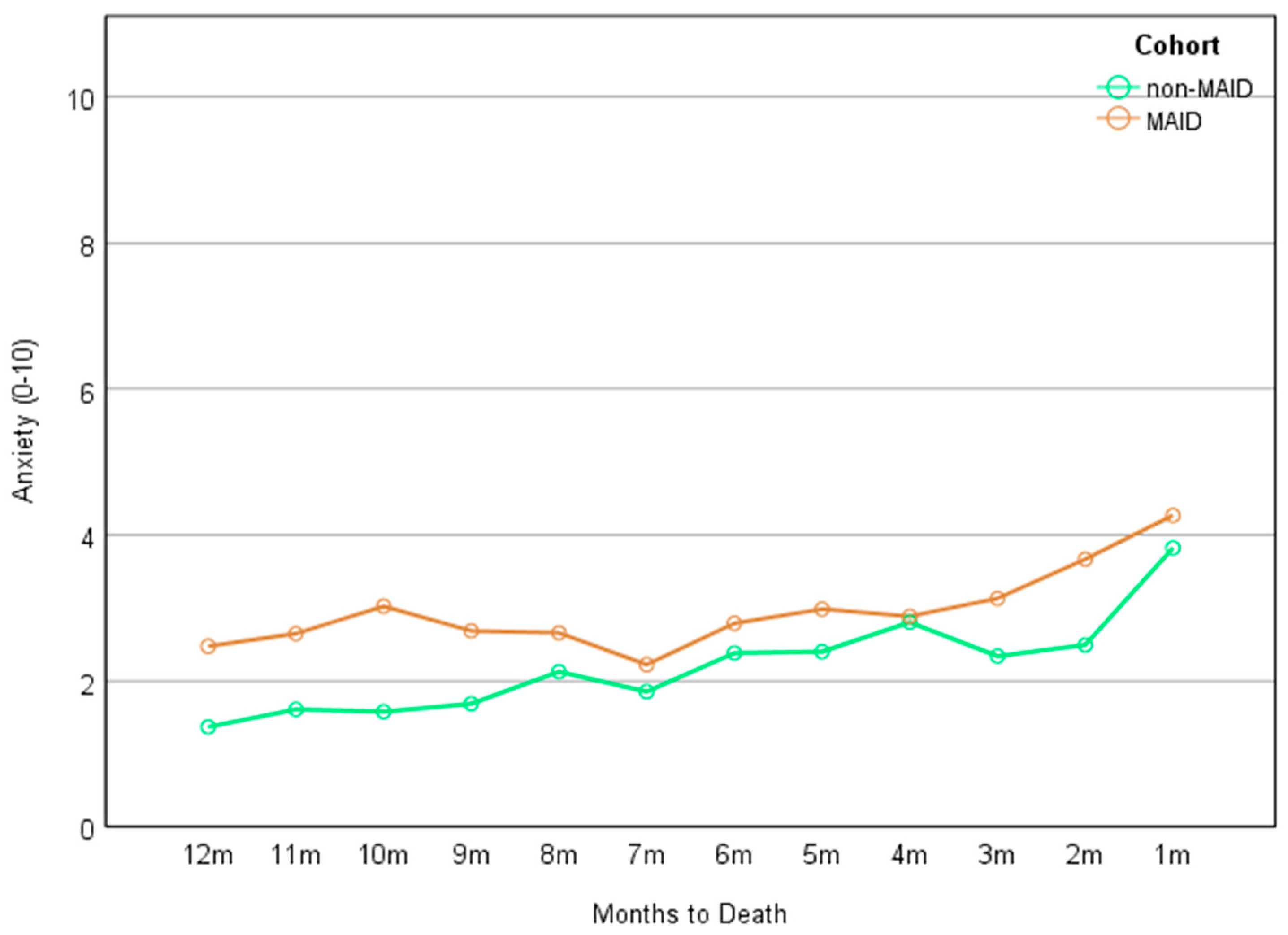

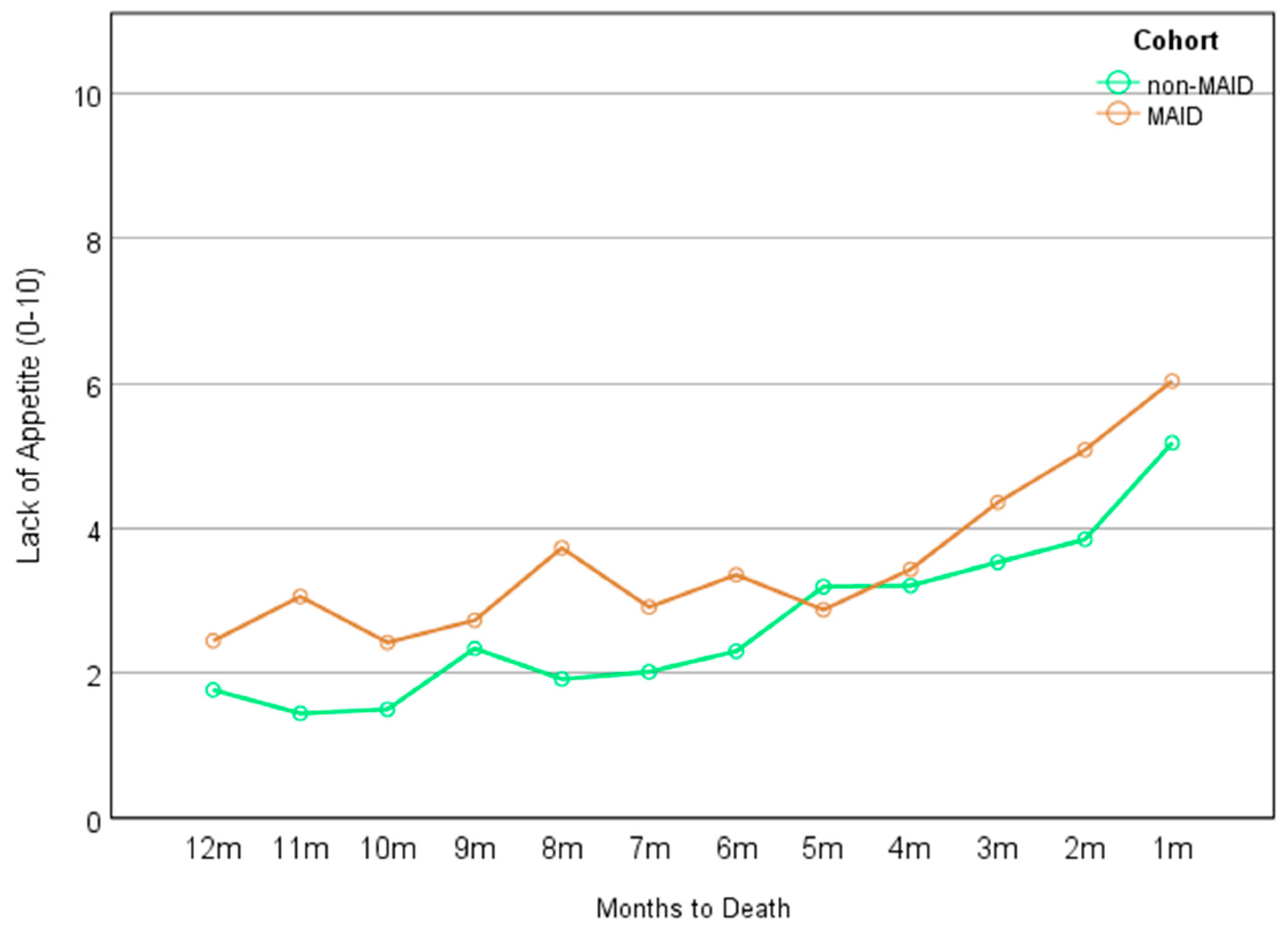

3.2. Symptom Trajectories

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lage, D.E.; El-Jawahri, A.; Fuh, C.X.; Newcomb, R.A.; Jackson, V.A.; Ryan, D.P.; Greer, J.A.; Temel, J.S.; Nipp, R.D. Functional impairment, symptom burden, and clinical outcomes among hospitalized patients with advanced cancer. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2020, 18, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Chan, M.; Bhatti, H.; Halton, M.; Grassi, L.; Johansen, C.; Meader, N. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: A meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, P.; Lo, C.; Li, M.; Gagliese, L.; Zimmermann, C.; Rodin, G. The relationship between depression and physical symptom burden in advanced cancer. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2015, 5, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, S.; Walsh, D.; Rybicki, L. The symptoms of advanced cancer: Identification of clinical and research priorities by assessment of prevalence and severity. J. Palliat Care 1995, 11, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano, J.P.; Gomes, B.; Higginson, I.J. A comparison of symptom prevalence in far advanced cancer, aids, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and renal disease. J. Pain Symptom. Manag. 2006, 31, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainio, A.; Auvinen, A. Prevalence of symptoms among patients with advanced cancer: An international collaborative study. Symptom prevalence group. J. Pain Symptom. Manag. 1996, 12, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doorenbos, A.Z.; Given, C.W.; Given, B.; Verbitsky, N. Symptom experience in the last year of life among individuals with cancer. J. Pain Symptom. Manag. 2006, 32, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleeland, C.S. Symptom burden: Multiple symptoms and their impact as patient-reported outcomes. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2007, 2007, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausewein, C.; Booth, S.; Gysels, M.; Kuhnbach, R.; Haberland, B.; Higginson, I.J. Understanding breathlessness: Cross-sectional comparison of symptom burden and palliative care needs in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cancer. J. Palliat. Med. 2010, 13, 1109–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, A.; Yang, L.; Boyne, D.J.; Harper, A.; Cuthbert, C.A.; Cheung, W.Y. Symptom burden in patients with common cancers near end-of-life and its associations with clinical characteristics: A real-world study. Support Care Cancer 2021, 29, 3299–3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, W.Y.; Barmala, N.; Zarinehbaf, S.; Rodin, G.; Le, L.W.; Zimmermann, C. The association of physical and psychological symptom burden with time to death among palliative cancer outpatients. J. Pain Symptom. Manag. 2009, 37, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Smith, T.G.; Michonski, J.D.; Stein, K.D.; Kaw, C.; Cleeland, C.S. Symptom burden in cancer survivors 1 year after diagnosis: A report from the american cancer society’s studies of cancer survivors. Cancer 2011, 117, 2779–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desbiens, N.A.; Mueller-Rizner, N.; Connors, A.F., Jr.; Wenger, N.S.; Lynn, J. The symptom burden of seriously ill hospitalized patients. Support investigators. Study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcome and risks of treatment. J. Pain Symptom. Manag. 1999, 17, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshields, T.L.; Potter, P.; Olsen, S.; Liu, J. The persistence of symptom burden: Symptom experience and quality of life of cancer patients across one year. Support Care Cancer 2014, 22, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrl, K.; Guren, M.G.; Astrup, G.L.; Smastuen, M.C.; Rustoen, T. High symptom burden is associated with impaired quality of life in colorectal cancer patients during chemotherapy:A prospective longitudinal study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 44, 101679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downar, J.; Wegier, P.; Tanuseputro, P. Early identification of people who would benefit from a palliative approach-moving from surprise to routine. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1911146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, J.R.; Temel, J.S. The integration of early palliative care with oncology care: The time has come for a new tradition. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2014, 12, 1763–1771; quiz 1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An Act to Amend the Criminal Code and to Make Related Amendments to Other Acts (Medical Assistance in Dying). 2016. Available online: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/annualstatutes/2016_3/fulltext.html (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- An Act to Amend the Criminal Code (Medical Assistance in Dying), in C-7. 2021. Available online: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/pl/charter-charte/c7.html (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Third Annual Report on Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada 2021; Health Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2022.

- Watson, L.; Link, C.; Qi, S.; DeIure, A.; Russell, K.B.; Schulte, F.; Forbes, C.; Silvius, J.; Kelly, B.; Bultz, B.D. Symptom burden and complexity in the last 12 months of life among cancer patients choosing medical assistance in dying (maid) in alberta, Canada. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 1605–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (strobe) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. To use or not to use propensity score matching? Pharm. Stat. 2021, 20, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, P.C. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2011, 46, 399–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetto, U.; Head, S.J.; Angelini, G.D.; Blackstone, E.H. Statistical primer: Propensity score matching and its alternatives. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2018, 53, 1112–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.M.; Nekolaichuk, C.; Beaumont, C.; Johnson, L.; Myers, J.; Strasser, F. A multicenter study comparing two numerical versions of the edmonton symptom assessment system in palliative care patients. J. Pain Symptom. Manag. 2011, 41, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekolaichuk, C.; Watanabe, S.; Beaumont, C. The edmonton symptom assessment system: A 15-year retrospective review of validation studies (1991–2006). Palliat. Med. 2008, 22, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accreditation Canada. Cchsa’s Qmentum Accreditation Program: Service Excellence—2008, Sector and Service-Based Standards, Cancer Care; Oncology Services: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, L.; Qi, S.; DeIure, A.; Link, C.; Chmielewski, L.; Hildebrand, A.; Rawson, K.; Ruether, D. Using autoregressive integrated moving average (arima) modelling to forecast symptom complexity in an ambulatory oncology clinic: Harnessing predictive analytics and patient-reported outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Services, A.H. Official Standard Geographic Areas; Alberta Health Services and Alberta Heath: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J. Chronic. Dis. 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deyo, R.A.; Cherkin, D.C.; Ciol, M.A. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with icd-9-cm administrative databases. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1992, 45, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, H.; Sundararajan, V.; Halfon, P.; Fong, A.; Burnand, B.; Luthi, J.C.; Saunders, L.D.; Beck, C.A.; Feasby, T.E.; Ghali, W.A. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in icd-9-cm and icd-10 administrative data. Med. Care 2005, 43, 1130–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanford, S.D.; Beaumont, J.L.; Butt, Z.; Sweet, J.J.; Cella, D.; Wagner, L.I. Prospective longitudinal evaluation of a symptom cluster in breast cancer. J. Pain Symptom. Manag. 2014, 47, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbera, L.; Atzema, C.; Sutradhar, R.; Seow, H.; Howell, D.; Husain, A.; Sussman, J.; Earle, C.; Liu, Y.; Dudgeon, D. Do patient-reported symptoms predict emergency department visits in cancer patients? A population-based analysis. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2013, 61, 427–437.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singmann, H.; Kellen, D. An introduction to mixed models for experimental psychology. In New Methods in Cognitive Psychology; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 4–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Han, Y.; Kim, J.R.; Kwon, W.; Kim, S.W.; Jang, J.Y. Preoperative biliary drainage adversely affects surgical outcomes in periampullary cancer: A retrospective and propensity score-matched analysis. J. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018, 25, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seow, H.; Sutradhar, R.; Burge, F.; McGrail, K.; Guthrie, D.M.; Lawson, B.; Oz, U.E.; Chan, K.; Peacock, S.; Barbera, L. End-of-life outcomes with or without early palliative care: A propensity score matched, population-based cancer cohort study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e041432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisic, L.; Strowitzki, M.J.; Blank, S.; Nienhueser, H.; Dorr, S.; Haag, G.M.; Jager, D.; Ott, K.; Buchler, M.W.; Ulrich, A.; et al. Postoperative follow-up programs improve survival in curatively resected gastric and junctional cancer patients: A propensity score matched analysis. Gastric. Cancer 2018, 21, 552–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Chang, C.L.; Lu, C.Y.; Zhang, J.; Wu, S.Y. Effect of opioids on cancer survival in patients with chronic pain: A propensity score-matched population-based cohort study. Br. J. Anaesth. 2022, 128, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedard, G.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, L.; Lauzon, N.; Holden, L.; Tsao, M.; Danjoux, C.; Barnes, E.; Sahgal, A.; Poon, M.; et al. Minimal clinically important differences in the edmonton symptom assessment system in patients with advanced cancer. J. Pain Symptom. Manag. 2013, 46, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Shamieh, O.; Paiva, C.E.; Perez-Cruz, P.E.; Kwon, J.H.; Muckaden, M.A.; Park, M.; Yennu, S.; Kang, J.H.; Bruera, E. Minimal clinically important differences in the edmonton symptom assessment scale in cancer patients: A prospective, multicenter study. Cancer 2015, 121, 3027–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroz, S.; Dierickx, S.; Deliens, L.; Cohen, J.; Chambaere, K. Assisted dying around the world: A status quaestionis. Ann. Palliat Med. 2021, 10, 3540–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duijn, J.M.; Zweers, D.; Kars, M.C.; de Graeff, A.; Teunissen, S. Anxiety in hospice inpatients with advanced cancer, from the perspective of their informal caregivers: A qualitative study. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2021, 23, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.T.; Chen, J.S.; Chou, W.C.; Chang, W.C.; Wu, C.E.; Hsieh, C.H.; Chiang, M.C.; Kuo, M.L. Longitudinal analysis of severe anxiety symptoms in the last year of life among patients with advanced cancer: Relationships with proximity to death, burden, and social support. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2016, 14, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neel, C.; Lo, C.; Rydall, A.; Hales, S.; Rodin, G. Determinants of death anxiety in patients with advanced cancer. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2015, 5, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, D.; Cohen, J.N.; Mennin, D.S.; Fresco, D.M.; Heimberg, R.G. Clarifying the unique associations among intolerance of uncertainty, anxiety, and depression. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2016, 45, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.; Burden, S.T.; Cheng, H.; Molassiotis, A. Understanding and managing cancer-related weight loss and anorexia: Insights from a systematic review of qualitative research. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2015, 6, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrevall, Y.; Tishelman, C.; Herrington, M.K.; Permert, J. The path from oral nutrition to home parenteral nutrition: A qualitative interview study of the experiences of advanced cancer patients and their families. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 23, 1280–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association, A.P. Anxiety disorders. In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ruijs, C.D.; van der Wal, G.; Kerkhof, A.J.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.D. Unbearable suffering and requests for euthanasia prospectively studied in end-of-life cancer patients in primary care. BMC Palliat. Care 2014, 13, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, B.B.; Mitchell, S.A.; Dueck, A.C.; Basch, E.; Cella, D.; Reilly, C.M.; Minasian, L.M.; Denicoff, A.M.; O’Mara, A.M.; Fisch, M.J.; et al. Recommended patient-reported core set of symptoms to measure in adult cancer treatment trials. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, dju129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bultz, B.D.; Waller, A.; Cullum, J.; Jones, P.; Halland, J.; Groff, S.L.; Leckie, C.; Shirt, L.; Blanchard, S.; Lau, H.; et al. Implementing routine screening for distress, the sixth vital sign, for patients with head and neck and neurologic cancers. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2013, 11, 1249–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, P.B.; Ransom, S. Implementation of nccn distress management guidelines by member institutions. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2007, 5, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshields, T.L.; Wells-Di Gregorio, S.; Flowers, S.R.; Irwin, K.E.; Nipp, R.; Padgett, L.; Zebrack, B. Addressing distress management challenges: Recommendations from the consensus panel of the american psychosocial oncology society and the association of oncology social work. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 407–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Batra, A.; Yang, L.; Boyne, D.J.; Harper, A.; Ghatage, P.; Cuthbert, C.A.; Cheung, W.Y. Patient-reported symptom burden near the end of life in patients with gynaecologic cancers. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2021, 43, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, P.B.; Schrag, D.; Begg, C.B. Resurrecting treatment histories of dead patients: A study design that should be laid to rest. JAMA 2004, 292, 2765–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starks, H.; Diehr, P.; Curtis, J.R. The challenge of selection bias and confounding in palliative care research. J. Palliat. Med. 2009, 12, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earle, C.C.; Ayanian, J.Z. Looking back from death: The value of retrospective studies of end-of-life care. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 838–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Before PSM | After PSM | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAID Cohort (n = 149) a | Full Non-MAID Cohort (n = 486) a | p | MAID Cohort (n = 149) a | Matched Non-MAID Cohort (n = 149) a | p | |

| Age at death [mean (SD)] | 68.7 (11.8) | 72.5 (12.6) | .001 | 68.7 (11.8) | 67.4 (11.2) | .346 |

| Sex: | .499 | .163 | ||||

| Female | 74 (49.7%) | 226 (46.5%) | 74 (49.7%) | 62 (41.6%) | ||

| Male | 75 (50.3%) | 260 (53.5%) | 75 (50.3%) | 87 (58.4%) | ||

| Marital status: | .677 | .557 | ||||

| Married/in common-law relationship | 84 (56.4%) | 227 (58.4%) | 84 (56.4%) | 89 (59.7%) | ||

| Single/widowed/divorced/separated | 65 (43.6%) | 162 (41.6%) | 65 (43.6%) | 60 (40.3%) | ||

| Rurality: | .000 | .712 | ||||

| Metro | 113 (75.8%) | 282 (58.1%) | 113 (75.8%) | 112 (75.2%) | ||

| Urban | 16 (10.7%) | 66 (13.6%) | 16 (10.7%) | 13 (8.7%) | ||

| Rural | 20 (13.4%) | 137 (28.2%) | 20 (13.4%) | 24 (16.1%) | ||

| Neighborhood-level income quintile: | .005 | .461 | ||||

| 1 (USD 19,968–USD 62,933) (lowest) | 22 (14.8%) | 100 (20.7%) | 22 (14.8%) | 30 (20.1%) | ||

| 2 (USD 63,040–USD 77,248) | 25 (16.8%) | 112 (23.2%) | 25 (16.8%) | 31 (20.8%) | ||

| 3 (USD 77,312–USD 96,000) | 23 (15.4%) | 94 (19.5%) | 23 (15.4%) | 17 (11.4%) | ||

| 4 (USD 96,256–USD 120,064) | 33 (22.1%) | 91 (18.8%) | 33 (22.1%) | 26 (17.4%) | ||

| 5 (USD 120,192–USD 312,320) (highest) | 46 (30.9%) | 86 (17.8%) | 46 (30.9%) | 45 (30.2%) | ||

| Birth country: | .208 | .878 | ||||

| Canada | 125 (83.9%) | 306 (79.1%) | 125 (83.9%) | 124 (83.2%) | ||

| Outside of Canada (high income) | 24 (16.1%) | 81 (20.9%) | 24 (16.1%) | 25 (16.8%) | ||

| Tumor group: | .003 | .899 | ||||

| Breast | 13 (8.7%) | 46 (9.5%) | 13 (8.7%) | 13 (8.7%) | ||

| Gastrointestinal | 44 (29.5%) | 150 (30.9%) | 44 (29.5%) | 43 (28.9%) | ||

| Genitourinary | 14 (9.4%) | 55 (11.3%) | 14 (9.4%) | 21 (14.1%) | ||

| Gynecology | 17 (11.4%) | 24 (4.9%) | 17 (11.4%) | 14 (9.4%) | ||

| Hematology | 15 (10.1%) | 51 (10.5%) | 15 (10.1%) | 12 (8.1%) | ||

| Lung | 23 (15.4%) | 122 (25.1%) | 23 (15.4%) | 25 (16.8%) | ||

| Other b | 23 (15.4%) | 38 (7.8%) | 23 (15.4%) | 21 (14.1%) | ||

| Age at diagnosis: | .000 | .948 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 64.0 (12.3) | 69.2 (13.1) | 64.0 (12.3) | 64.1 (10.8) | ||

| CCI: | .000 | .900 | ||||

| 0 | 104 (69.8%) | 207 (42.6%) | 104 (69.8%) | 103 (69.1%) | ||

| ≥1 | 45 (30.2%) | 279 (57.4%) | 45 (30.2%) | 46 (30.9%) | ||

| Cohort a | Time b | Interaction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | p | β (95% CI) | p | β (95% CI) | p | |

| Pain | −0.305 (−1.104–0.493) | .453 | 0.223 (0.161–0.287) | .000 | −0.016 (−0.100–0.068) | .709 |

| Tiredness | −0.211 (−1.001–0.586) | .602 | 0.231 (0.169–0.294) | .000 | −0.038 (−0.123–0.046) | .372 |

| Drowsiness | −0.381 (−1.185–0.424) | .353 | 0.219 (0.156–0.281) | .000 | −0.076 (−0.160–0.008) | .077 |

| Nausea | −0.172 (−0.859–0.516) | .624 | 0.175 (0.119–0.231) | .000 | −0.064 (−0.139–0.012) | .101 |

| Lack of appetite | −0.934 (−1.823–−0.016) | .039 | 0.230 (0.159–0.301) | .000 | 0.046 (−0.050–0.141) | .348 |

| Shortness of breath | −0.379 (−1.174–0.417) | .350 | 0.171 (0.112–0.230) | .000 | −0.002 (−0.081–0.078) | .969 |

| Depression | −0.106 (−0.902–0.688) | .792 | 0.164 (0.111–0.217) | .000 | −0.039 (−0.110–0.031) | .275 |

| Anxiety | −0.831 (−1.641–−0.022) | .044 | 0.086 (0.030–0.141) | .002 | 0.044 (−0.030–0.119) | .246 |

| Wellbeing | −0.107 (−0.888–0.675) | .789 | 0.231 (0.170–0.291) | .000 | −0.043 (−0.125–0.039) | .308 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Russell, K.B.; Forbes, C.; Qi, S.; Link, C.; Watson, L.; Deiure, A.; Lu, S.; Silvius, J.; Kelly, B.; Bultz, B.D.; et al. End-of-Life Symptom Burden among Patients with Cancer Who Were Provided Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID): A Longitudinal Propensity-Score-Matched Cohort Study. Cancers 2024, 16, 1294. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16071294

Russell KB, Forbes C, Qi S, Link C, Watson L, Deiure A, Lu S, Silvius J, Kelly B, Bultz BD, et al. End-of-Life Symptom Burden among Patients with Cancer Who Were Provided Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID): A Longitudinal Propensity-Score-Matched Cohort Study. Cancers. 2024; 16(7):1294. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16071294

Chicago/Turabian StyleRussell, K. Brooke, Caitlin Forbes, Siwei Qi, Claire Link, Linda Watson, Andrea Deiure, Shuang Lu, James Silvius, Brian Kelly, Barry D. Bultz, and et al. 2024. "End-of-Life Symptom Burden among Patients with Cancer Who Were Provided Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID): A Longitudinal Propensity-Score-Matched Cohort Study" Cancers 16, no. 7: 1294. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16071294

APA StyleRussell, K. B., Forbes, C., Qi, S., Link, C., Watson, L., Deiure, A., Lu, S., Silvius, J., Kelly, B., Bultz, B. D., & Schulte, F. (2024). End-of-Life Symptom Burden among Patients with Cancer Who Were Provided Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID): A Longitudinal Propensity-Score-Matched Cohort Study. Cancers, 16(7), 1294. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16071294