Simple Summary

Spinal schwannomas are the second most common primary intradural spinal tumor. Although these tumors are histologically benign, they can cause spinal cord compression with acute or chronic neurological deficits. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) can be described as quality of life relative to a person’s health or disease status and HRQoL measures may therefore be considered as measures of self-perceived status. Despite the fact that some studies have evaluated the neurological outcomes after surgery for spinal schwannomas, no studies have been conducted on HRQoL and return to work after surgery. In this population-based cohort study, 94 cases of surgically treated spinal schwannomas were followed for a median 7.3 years [4.8–10.6] to assess their HRQoL compared to a sample of the general population. We found that HRQoL was equal between the spinal schwannoma sample and the general population sample in all but one dimension; men in the spinal schwannoma sample reported more moderate problems in the usual activities dimension than men in the general population. The frequency of return to work was 94%. Thus, surgery of spinal schwannomas should be considered a safe procedure with good long-term HRQoL.

Abstract

Spinal schwannomas are the second most common primary intradural spinal tumor. This study aimed to assess health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and the frequency of return to work after the surgical treatment of spinal schwannomas. HRQoL was compared to a sample of the general population. Patients operated for spinal schwannomas between 2006 and 2020 were identified in a previous study and those alive at follow-up (171 of 180) were asked to participate. Ninety-four (56%) responded and were included in this study. Data were compared to the Stockholm Public Health Survey 2006, a cross-sectional survey of a representative sample of the general population. An analysis for any potential non-response bias was performed and showed no significant differences between the groups. HRQoL was equal between the spinal schwannoma sample and the general population sample in all but one dimension; men in the spinal schwannoma sample reported more moderate problems in the usual activities dimension than men in the general population (p = 0.020). In the schwannoma sample, there were no significant differences between men and women in either of the dimensions EQ-5Dindex or EQVAS. Before surgery, a total of 71 (76%) were working full-time and after surgery almost all (94%) returned to work, most of them within 3 months of surgery. Eighty-nine (95%) of the patients responded that they would accept the surgery for their spinal schwannoma if asked again today. To conclude, surgical treatment of spinal schwannomas is associated with good HRQoL and with a high frequency of return to work.

1. Introduction

Schwannomas are WHO grade 1 nerve sheath tumors that may affect peripheral, spinal, or cranial nerves [1,2,3,4]. Spinal schwannomas comprise 25% of all intradural spinal cord tumors [2,5,6] with an incidence of 0.3–0.7 per 100,000 [7]. Although benign, large schwannomas can compress nerve roots or the spinal cord, resulting in neurological deficits. Surgery with the aim of gross total resection is the treatment of choice [2,8,9]. Surgical resection is performed to improve the neurological function or halt neurological deterioration and alleviate pain. Surgical treatment of spinal schwannomas is typically associated with postoperative neurological improvements [1]. However, there are few studies on patient-reported outcomes, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) or return to work after surgery for spinal schwannomas [10,11].

HRQoL can be described as quality of life relative to a person’s health or disease status [12], and HRQoL measures may therefore be considered as measures of self-perceived health status [13]. HRQoL is dynamic, subjective and multidimensional [12]. Most conceptualizations of HRQoL include different dimensions of functioning, such as physical functioning, social functioning, role functioning and mental health and, further, patients’ perceptions of general health and symptoms [14]. In the Swedish general population, HRQoL reporting differs between sexes. Women generally report more problems within the dimensions anxiety/depression and pain/discomfort and have lower overall HRQoL in comparison to men of the same ages. Moreover, the number of reported problems increases with age [15]. Subsequently, when HRQoL comparisons are made with the general population, the samples need to be matched by both sex and age.

Previous studies have also highlighted that an individual’s ability to work and the possibility of returning to work after surgery have a great impact on quality of life [15,16,17,18,19,20]

Given the paucity of studies on the topic, the aim of this study was to explore long-term HRQoL and return to work in a consecutive cohort of patients surgically treated for spinal schwannomas. The same cohort was previously investigated for neurological outcomes after surgery [1].

2. Materials and Methods

This population-based cohort study compared HRQoL data from a spinal schwannoma sample with a general population sample. The HRQoL data and employment data were self-reported in EQ-5D-3L and a study-specific questionnaire.

2.1. Samples

2.1.1. Spinal Schwannoma Sample

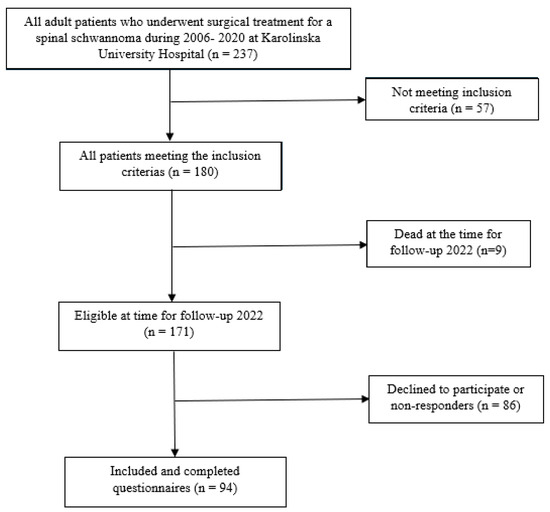

All adult (≥18 years) patients operated for a spinal schwannoma at the Karolinska University Hospital during a period of 15 years (2006–2020) were identified in a previous study including 180 patients [1]. Of these 180 patients, 171 were still alive in 2022 and were contacted with a request for participation in this follow-up study. A total of 86 patients declined to participate or did not respond. Thus, 94 spinal schwannoma patients were included in the study (55% of eligible patients; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the patient inclusion process.

2.1.2. General Population Sample

To compare HRQoL data with the general population, data from the Stockholm Public Health Survey 2006 were used. This was a cross-sectional survey of a representative sample of the general population in Stockholm County. A self-reported postal questionnaire, including the EQ-5D-3L instrument, was sent to 57,000 adult persons aged 18–84 years, with a response rate of 61%. Anonymized raw data were obtained, and for each one of the 94 spinal schwannoma patients that answered the EQ-5D-3L, three control subjects were randomly selected and individually matched by sex and age by the statistical program SPSS (Version 25, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Consequently, 282 individuals were included in the general population sample, intended to mirror the population in the Stockholm region. Three women in the spinal schwannoma sample were older than 84 years (aged 85, 87 and 91 years); their controls were therefore matched with the oldest controls, aged 84 years old.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. EQ-5D-3L

The generic HRQoL questionnaire EQ-5D-3L consists of two parts: a descriptive system where the respondents classify their health in five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression) within three severity levels (no problems, moderate problems or severe problems), and a visual analogue scale (EQVAS) [21]. The response in each dimension of the descriptive system generates a 5-digit value which can be indexed into a single overall HRQoL value, the EQ-5Dindex, where 0 represents dead and 1 represents full health. On EQVAS, the respondents rate their current health between the two anchor points 0 (worst imaginable health) and 100 (best imaginable health). The recall period is the day of completion of the questionnaire. In this study, the United Kingdom (UK) value set was used to calculate the EQ-5Dindex [22] to enable international comparisons of index values.

2.2.2. Study-Specific Questionnaire

A study-specific questionnaire was designed with multiple choice questions. The first part of the questionnaire regarded neurological symptoms (motor deficit, sensory deficit, balance, and incontinence) and how these symptoms had changed compared to preoperative status. The patients were also asked whether they would accept to undergo the same surgery if they had been offered it today. Questions were also asked about comorbidities and current medication due to residual symptoms of the tumor. The final part of the questionnaire concerned employment status, sick-leave and return to work after surgery.

2.2.3. Clinical Parameters

Clinical parameters including the modified McCormick score (mMC), symptom duration, tumor recurrence and details of surgical procedure were derived from previously published data [1].

2.3. Data Analysis

A non-response analysis was conducted, considering all baseline variables (Supplementary Table S1).

EQ-5D-3L data were compared between the spinal schwannoma sample and the general population sample, and sub-group comparisons were made between males and females. To analyze differences between groups, a Fisher’s exact test and an independent samples median test with Yates’s continuity correction were used. Moderate and severe levels on EQ-5D-3L dimensions were collapsed before analysis. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

A signed informed consent was obtained from each participant in the spinal schwannoma sample. Anonymized data from the Stockholm Public Health Survey were obtained after ethical approval. The Stockholm Public Health Survey contains data from individuals who have provided consent. The study was approved by the Regional and National Ethical Review Board (Dnr: 2016/1708-31/4 and 2021-05249).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline and Characteristics of the Sample

In total, 94 patients were included in this study. The median age at the time of surgery was 52 [42–64] years and 45 (48%) were men. At follow-up, the median age was 59 [52–71]. The median follow-up time after surgery was 7.3 years [4.8–11]. The most common presenting symptom was pain, and the median time between symptom debut and surgery was 12 months. Considering neurological function according to the mMC scale, 40 patients (42%) improved, 44 (47%) were unchanged and 10 (11%) worsened. Notably, 35 patients (37%) were mMC I before surgery and could therefore not improve. The most common laminectomy ranges were two (59%) and three levels (23%). A laminoplasty was performed in 51 (54%) cases (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the spinal schwannoma sample.

3.2. Comparison of HRQoL between the Spinal Schwannoma Sample and the General Population Sample

HRQoL was equal between the spinal schwannoma sample and the general population sample in all but one dimension; men in the spinal schwannoma sample reported significantly more problems in the usual activities dimension than the men in the general population sample (p = 0.020) (Table 2). In this study, women in both samples reported more problems than the men in the pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression dimensions, but the differences were only significant in the general population sample (p = 0.043 and p = 0,050, respectively). In the schwannoma sample, there were no significant differences between men and women in any dimension of EQ-5D or EQVAS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Percentage (number) of respondents reporting no, moderate and severe problems in EQ-5D dimensions, EQ-5Dindex and EQVAS, spinal schwannoma sample and general population sample.

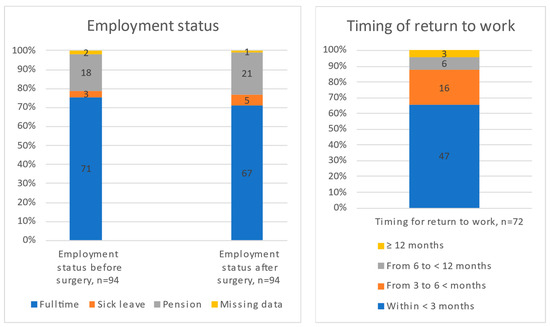

3.3. Employment Status and Return to Work after Spinal Schwannoma Surgery

Before surgery, a total of 71 (76%) of the spinal schwannoma patients were working full-time (Figure 2). Of those who worked before surgery, 67 (94%) had returned to work at follow-up, while 3 patients (4%) had received the old age pension. The majority returned to work within 3 months (70%) (Figure 2). At follow-up, 5 patients were on sick leave, but the cause was unknown.

Figure 2.

Employment status before and after surgery and timing of return to work.

3.4. Remaining Symptoms and Patient Reported Outcomes

Sixty-four (68%) patients reported at least one remaining symptom in the study-specific questionnaire (Table 3). Thirty-eight (40%) reported improvements in their symptoms postoperatively, thirty-five (37%) reported no change in their symptoms and seventeen (18%) patients felt their symptoms had worsened postoperatively. Four (4.3%) patients did not answer this question. Eighty-nine (95%) of the patients responded that they would accept the surgery if asked again today. Five patients would not accept the surgery if it was offered today. Three of those five said no because of a complication, while two said no because of the absence of improvement or a worsened neurological status.

Table 3.

Patient reported remaining symptoms and medication.

3.5. Comorbidity

The Charlson comorbidity index was in median 1 [0–2], indicating that the schwannoma patients had good general health (Table 1).

3.6. Medication

Sixty (64%) patients reported that they did not use any medication related to the surgery (Table 3). Thirty (32%) patients used non-prescription pain medication such as NSAID or Paracetamol after surgery. None of the patients used morphine derivates or spasticity (Baclofen) medication. Three (3.2%) patients used medication for neuropathic pain (Gabapentin or Pregabalin).

4. Discussion

In this study, the HRQoL of patients surgically treated for spinal schwannoma at long-term follow-up did not differ from the general population. Following surgical treatment for spinal schwannomas, patients reported pain, anxiety, mobility, and self-care scores comparable to those of the general population based on EQ5D assessments. A majority of the patients working before surgery returned to work (94%), and most of them within 3 months (70%). The most used medications were non-prescription analgesics (32%), and only 3.2% used prescription analgesics, such as neuropathic pain medication. None of the patients used morphine derivates or any spasticity medication.

Only a few studies have addressed the HRQoL after surgery for spinal schwannomas; most of them are studies in mixed groups of different intradural spinal tumors [23]. In a study of benign intradural extramedullary tumors, patients experienced statistically significant improvements regarding pain, work, mood, general activity, and enjoyment of life [24]. Viereck et al., reported that a resection of intradural spinal tumors improved HRQoL by decreasing patient disability and pain and improving each of the EQ-5D dimensions [11]. These findings are in accordance with our results. One important aspect of schwannomas, in contrast to meningiomas and myxopapillary ependymomas, is that schwannomas are often associated with radicular pain [8,9,25] and that the nerve root cannot always be preserved [1]. Thus, good surgical outcomes cannot be taken for granted, especially regarding long-term sensory deficits. The schwannoma sample reported similar general health problems to the matched controls. This may be a general pattern following surgery for a curable pathology. Previous studies have shown that non-curable conditions have a larger impact on HRQoL [26]. Despite 68% reporting remaining symptoms, only 18% reported a worsening and 95% would accept the surgery if offered it for the same diagnosis.

Due to the scarcity of HRQoL data on spinal schwannomas, other diagnoses were evaluated to provide a basis for comparison. Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) and spinal meningiomas share similarities in symptoms, anatomical structures affected, and in the surgical treatments used. Both spinal schwannomas and meningiomas belong to the group of benign intradural extramedullary tumors and are treated using similar approaches [27,28]. The initial symptoms for all three conditions include pain and neurological deficits secondary to compression of the spinal cord or nerves. In fact, Schwannomas may initially be misdiagnosed as LSS [29].

HRQoL was significantly improved following surgery for LSS [27,28]. A study using the Health Utilities Index Mark 3 (HUI3), where 1 represents perfect health, reported that the mean unadjusted overall scores were significantly lower for LSS (0.6) than the general population sample (0.85). Large differences in HRQoL remained after adjustment for sex and age [30]. A study by Pettersson-Segerlind et al. reported that the HRQoL of surgically treated spinal meningioma patients was equal to that of the general population. The EQ5Dindex and EQVAS for spinal meningiomas were 0.76 and 74 [31] and 0.8 and 80 for spinal schwannomas (current study), indistinguishable from the general population samples.

In a study on 58 patients with LSS, only 22% returned to work, while 38% did not feel like working again and 28% felt unfit for work. On a 0–100 scale comparable to EQvas, the domain scores for physical health, psychological health, social relations with friends and family or at work ranged from 59 to 61 on the WHOQOL-BREF, considerably lower than the range of 69 to 81 of the general population sample. However, the HRQoL of those who returned to work was similar to that of a healthy normal population [32]. Another study on 439 LSS patients showed that roughly 40% returned to work after surgery [33].

Pettersson-Segerlind et al. also showed that all patients who were working before surgery returned to work, in most cases within 3 months postoperatively [31]. These results are similar to the present study, suggesting that surgery for benign intradural extramedullary tumors is effective and leads to subjective recovery as well as an early return to work.

In summary, this study provides a first report on the HRQoL and return to work in spinal schwannoma patients compared to the general population. The findings provide new insights into the overall health and outcomes after surgery for spinal schwannomas, where previous data are lacking. The long-term, post-surgery, HRQoL of this cohort was comparable to that of the general population and patients with spinal meningiomas and much better than patients with LSS. The patients were satisfied with the surgery and almost all would accept the same treatment if offered it today.

Strengths and Limitations

The strength of this study is its population-based design and relatively large sample of spinal schwannoma patients. The follow-up duration was sufficient to enable the capture of long-term outcomes [34]. The surgeon bias was limited in this study by institutional routine since all referred cases of spinal schwannomas with imminent or manifest nerve root or spinal cord compression were offered surgery.

The general population sample was retrieved from the same Swedish region and was matched by sex and age since the HRQoL differs between sexes and ages [15]. The general population sample also included respondents with chronic diseases and not only healthy individuals.

Of the 180 consecutive patients, 9 had died and 86 did not participate. While we cannot exclude some selection bias, there were no differences in baseline parameters between those who responded to the questionnaire and those who did not (Supplementary Table S1). The matched controls were selected from a population sample with a 61% response rate, which may also have given an overly favorable assessment of HRQOL in this sample. We consider the data to be representative with external validity for surgically treated spinal schwannoma patients.

Previous studies have shown that non-response bias may affect the results of medical surveys [35,36,37]. The non-response becomes critical when response rates fall below 70%. The likelihood of non-response bias can be assessed by comparing baseline characteristics of responders and non-responders. A similarity in the baseline is reassuring but does not exclude the possibility of bias [38]. Therefore, the results of this study may be interpreted with caution in this regard.

A further limitation was that the study-specific questionnaire was not validated. However, questions included in the questionnaire mainly concerned symptoms, medication, and employment status, which were considered to have face validity.

5. Conclusions

Surgery for spinal schwannoma is safe and the results show a significant improvement in neurological function. The HRQoL was equal between the spinal schwannoma sample and the general population. The spinal schwannoma sample reported a limited use of pain medication and patients working preoperatively generally returned to work. Based on the findings of this study, surgical treatment of spinal schwannomas is associated with good HRQoL and with a high frequency of return to work.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cancers16101882/s1, Table S1: Illustrating that there is no bias between responders and non-responders.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S., A.-C.v.V., V.G.E.-H., J.P.-S., E.E. and A.E.-T.; formal analysis, A.-C.v.V.; investigation, A.S., A.-C.v.V., V.G.E.-H., J.P.-S., E.E. and A.E.-T.; resources, writing—original draft preparation, A.S., A.-C.v.V., V.G.E.-H., J.P.-S., A.F.-S., A.B., E.E. and A.E.-T.; writing—review and editing, A.S., A.-C.v.V., V.G.E.-H., J.P.-S., A.F.-S., A.B., E.E. and A.E.-T.; supervision, E.E. and A.E.-T.; project administration, A.E.-T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The author A.E.-T. was supported by Region Stockholm in a clinical research appointment.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the National Swedish Ethics Committee (Dnr: 2016/1708-31/4 and 2021-05249).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived according to Swedish law regarding retrospective research.

Data Availability Statement

Upon reasonable request, the data may be provided by contacting the corresponding author A.E.-T.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Singh, A.; Fletcher-Sandersjoo, A.; El-Hajj, V.G.; Burstrom, G.; Edstrom, E.; Elmi-Terander, A. Long-Term Functional Outcomes Following Surgical Treatment of Spinal Schwannomas: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Cancers 2024, 16, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emel, E.; Abdallah, A.; Sofuoglu, O.E.; Ofluoglu, A.E.; Gunes, M.; Guler, B.; Bilgic, B. Long-term Surgical Outcomes of Spinal Schwannomas: Retrospective Analysis of 49 Consecutive Cases. Turk. Neurosurg. 2017, 27, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Reifenberger, G.; von Deimling, A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Cavenee, W.K.; Ohgaki, H.; Wiestler, O.D.; Kleihues, P.; Ellison, D.W. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131, 803–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaith, A.K.; Johnson, S.E.; El-Hajj, V.G.; Akinduro, O.O.; Ghanem, M.; De Biase, G.; Michaelides, L.; Bon Nieves, A.; Marsh, W.R.; Currier, B.L.; et al. Surgical management of malignant melanotic nerve sheath tumors: An institutional experience and systematic review of the literature. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2024, 40, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohenberger, C.; Hinterleitner, J.; Schmidt, N.O.; Doenitz, C.; Zeman, F.; Schebesch, K.M. Neurological outcome after resection of spinal schwannoma. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2020, 198, 106127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, J.H.; Hwang, H.S.; Jeong, J.H.; Park, S.H.; Moon, J.G.; Kim, C.H. Spinal schwannoma; Analysis of 40 cases. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2008, 43, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlos-Escalante, J.A.; Paz-Lopez, A.A.; Cacho-Diaz, B.; Pacheco-Cuellar, G.; Reyes-Soto, G.; Wegman-Ostrosky, T. Primary Benign Tumors of the Spinal Canal. World Neurosurg. 2022, 164, 178–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottenhausen, M.; Ntoulias, G.; Bodhinayake, I.; Ruppert, F.H.; Schreiber, S.; Forschler, A.; Boockvar, J.A.; Jodicke, A. Intradural spinal tumors in adults-update on management and outcome. Neurosurg. Rev. 2019, 42, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarikaya, C.; Varol, E.; Cakici, Y.E.; Nader, I.S. Acute Neurologic Deterioration in Mobile Spinal Schwannoma. World Neurosurg. 2021, 146, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakarai, H.; Kato, S.; Yamato, Y.; Kodama, H.; Ohba, Y.; Sasaki, K.; Iizuka, T.; Tozawa, K.; Urayama, D.; Komatsu, N.; et al. Quality of Life and Postoperative Satisfaction in Patients with Benign Extramedullary Spinal Tumors: A Multicenter Study. Spine 2023, 48, E308–E316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viereck, M.J.; Ghobrial, G.M.; Beygi, S.; Harrop, J.S. Improved patient quality of life following intradural extramedullary spinal tumor resection. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2016, 25, 640–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakas, T.; McLennon, S.M.; Carpenter, J.S.; Buelow, J.M.; Otte, J.L.; Hanna, K.M.; Ellett, M.L.; Hadler, K.A.; Welch, J.L. Systematic review of health-related quality of life models. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2012, 10, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, M.; Brazier, J. Health, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Quality of Life: What is the Difference? Pharmacoeconomics 2016, 34, 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, I.B.; Cleary, P.D. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA 1995, 273, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burstrom, K.; Johannesson, M.; Diderichsen, F. Swedish population health-related quality of life results using the EQ-5D. Qual. Life Res. 2001, 10, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Materne, M.; Lundqvist, L.O.; Strandberg, T. Opportunities and barriers for successful return to work after acquired brain injury: A patient perspective. Work 2017, 56, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, J.D.; Bogner, J.A.; Mysiw, W.J.; Clinchot, D.; Fugate, L. Life satisfaction after traumatic brain injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2001, 16, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passier, P.E.; Visser-Meily, J.M.; Rinkel, G.J.; Lindeman, E.; Post, M.W. Life satisfaction and return to work after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2011, 20, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestling, M.; Tufvesson, B.; Iwarsson, S. Indicators for return to work after stroke and the importance of work for subjective well-being and life satisfaction. J. Rehabil. Med. 2003, 35, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burstrom, K.; Johannesson, M.; Rehnberg, C. Deteriorating health status in Stockholm 1998–2002: Results from repeated population surveys using the EQ-5D. Qual. Life Res. 2007, 16, 1547–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabin, R.; de Charro, F. EQ-5D: A measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann. Med. 2001, 33, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolan, P. Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med. Care 1997, 35, 1095–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chotai, S.; Zuckerman, S.L.; Parker, S.L.; Wick, J.B.; Stonko, D.P.; Hale, A.T.; McGirt, M.J.; Cheng, J.S.; Devin, C.J. Healthcare Resource Utilization and Patient-Reported Outcomes Following Elective Surgery for Intradural Extramedullary Spinal Tumors. Neurosurgery 2017, 81, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, W.C.; Berry-Candelario, J.; Villavieja, J.; Reiner, A.S.; Bilsky, M.H.; Laufer, I.; Barzilai, O. Improvement in Quality of Life Following Surgical Resection of Benign Intradural Extramedullary Tumors: A Prospective Evaluation of Patient-Reported Outcomes. Neurosurgery 2021, 88, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olex-Zarychta, D. Clinical Significance of Pain in Differential Diagnosis between Spinal Meningioma and Schwannoma. Case Rep. Oncol. Med. 2020, 26, 7947242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; von Vogelsang, A.C.; Tatter, C.; El-Hajj, V.G.; Fletcher-Sandersjoo, A.; Cewe, P.; Nilsson, G.; Blixt, S.; Gerdhem, P.; Edstrom, E.; et al. Dysphagia, health-related quality of life, and return to work after occipitocervical fixation. Acta Neurochir. 2024, 166, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, J.N.; Tosteson, T.D.; Lurie, J.D.; Tosteson, A.N.; Blood, E.; Hanscom, B.; Herkowitz, H.; Cammisa, F.; Albert, T.; Boden, S.D.; et al. Surgical versus nonsurgical therapy for lumbar spinal stenosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 794–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, G.D.; Kurd, M.F.; Vaccaro, A.R. Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: How Is It Classified? J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2016, 24, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, A.; Miyamoto, K.; Hosoe, H.; Shimizu, K. Thoracic paraplegia due to missed thoracic compressive lesions after lumbar spinal decompression surgery. Report of three cases. J. Neurosurg. 2004, 100 (Suppl. 1), 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Battie, M.C.; Jones, C.A.; Schopflocher, D.P.; Hu, R.W. Health-related quality of life and comorbidities associated with lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine J. 2012, 12, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson-Segerlind, J.; von Vogelsang, A.C.; Fletcher-Sandersjoo, A.; Tatter, C.; Mathiesen, T.; Edstrom, E.; Elmi-Terander, A. Health-Related Quality of Life and Return to Work after Surgery for Spinal Meningioma: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Cancers 2021, 13, 6371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truszczynska, A.; Rapala, K.; Truszczynski, O.; Tarnowski, A.; Lukawski, S. Return to work after spinal stenosis surgery and the patient’s quality of life. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2013, 26, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herno, A.; Airaksinen, O.; Saari, T.; Svomalainen, O. Pre- and postoperative factors associated with return to work following surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis. Am. J. Ind. Med. 1996, 30, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hajj, V.G.; Singh, A.; Blixt, S.; Edstrom, E.; Elmi-Terander, A.; Gerdhem, P. Evolution of patient-reported outcome measures, 1, 2, and 5 years after surgery for subaxial cervical spine fractures, a nation-wide registry study. Spine J. 2023, 23, 1182–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupp, I.; Triemstra, M.; Boshuizen, H.C.; Jacobi, C.E.; Dinant, H.J.; van den Bos, G.A. Selection bias due to non-response in a health survey among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Eur. J. Public Health 2002, 12, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, J.; Glass, N.; Fowler, T. Evidence of Selection Bias and Non-Response Bias in Patient Satisfaction Surveys. Iowa Orthop. J. 2019, 39, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cheung, K.L.; Ten Klooster, P.M.; Smit, C.; de Vries, H.; Pieterse, M.E. The impact of non-response bias due to sampling in public health studies: A comparison of voluntary versus mandatory recruitment in a Dutch national survey on adolescent health. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavson, K.; Roysamb, E.; Borren, I. Preventing bias from selective non-response in population-based survey studies: Findings from a Monte Carlo simulation study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).