Medication Adherence among Allogeneic Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients: A Systematic Review

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection Criteria

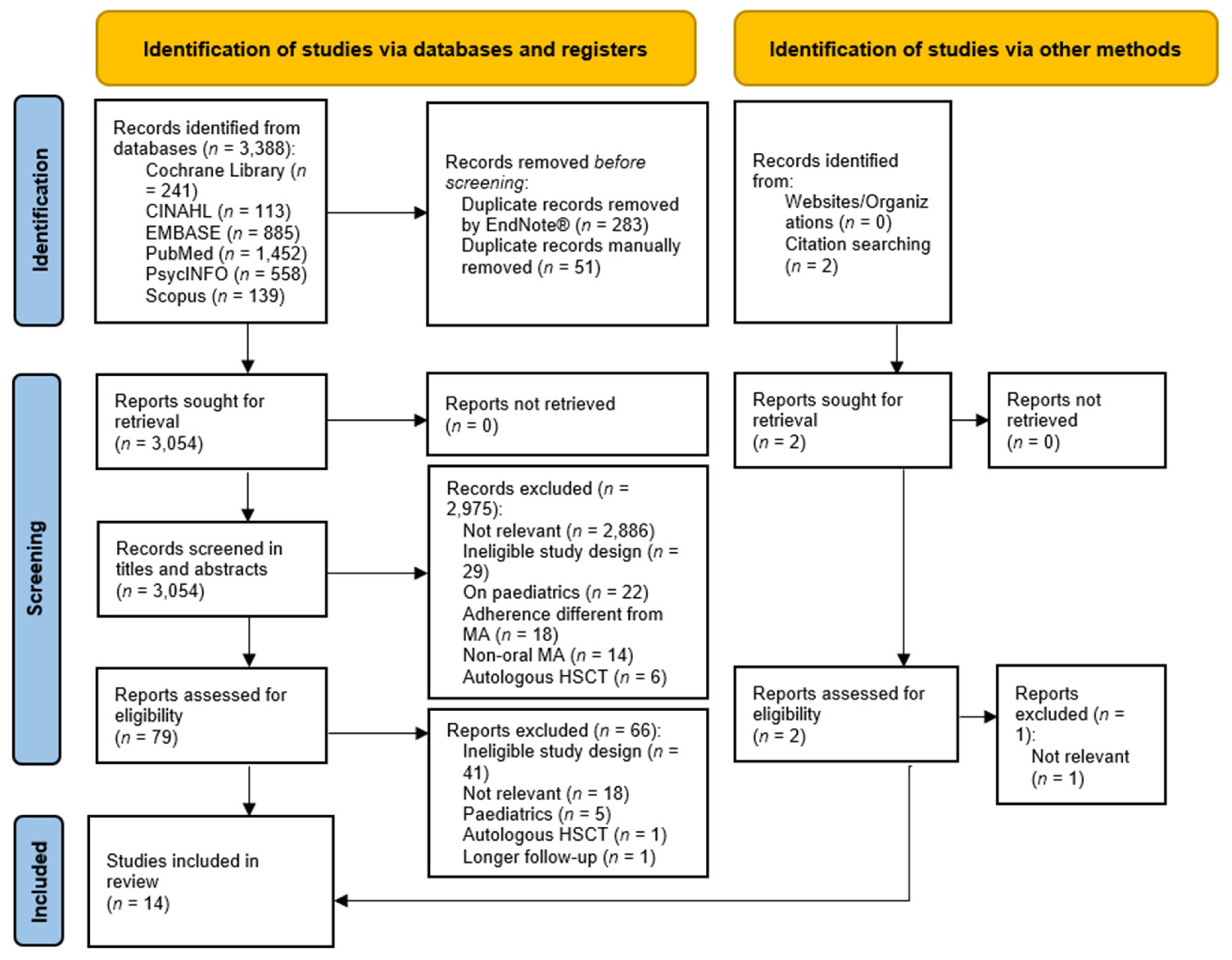

2.2. Study Selection and Search Strategy

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment and Confidence in the Cumulative Evidence

2.5. Data Analysis and Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Main Study Characteristics

3.2. Oral MA: Assessment Tools and Rates

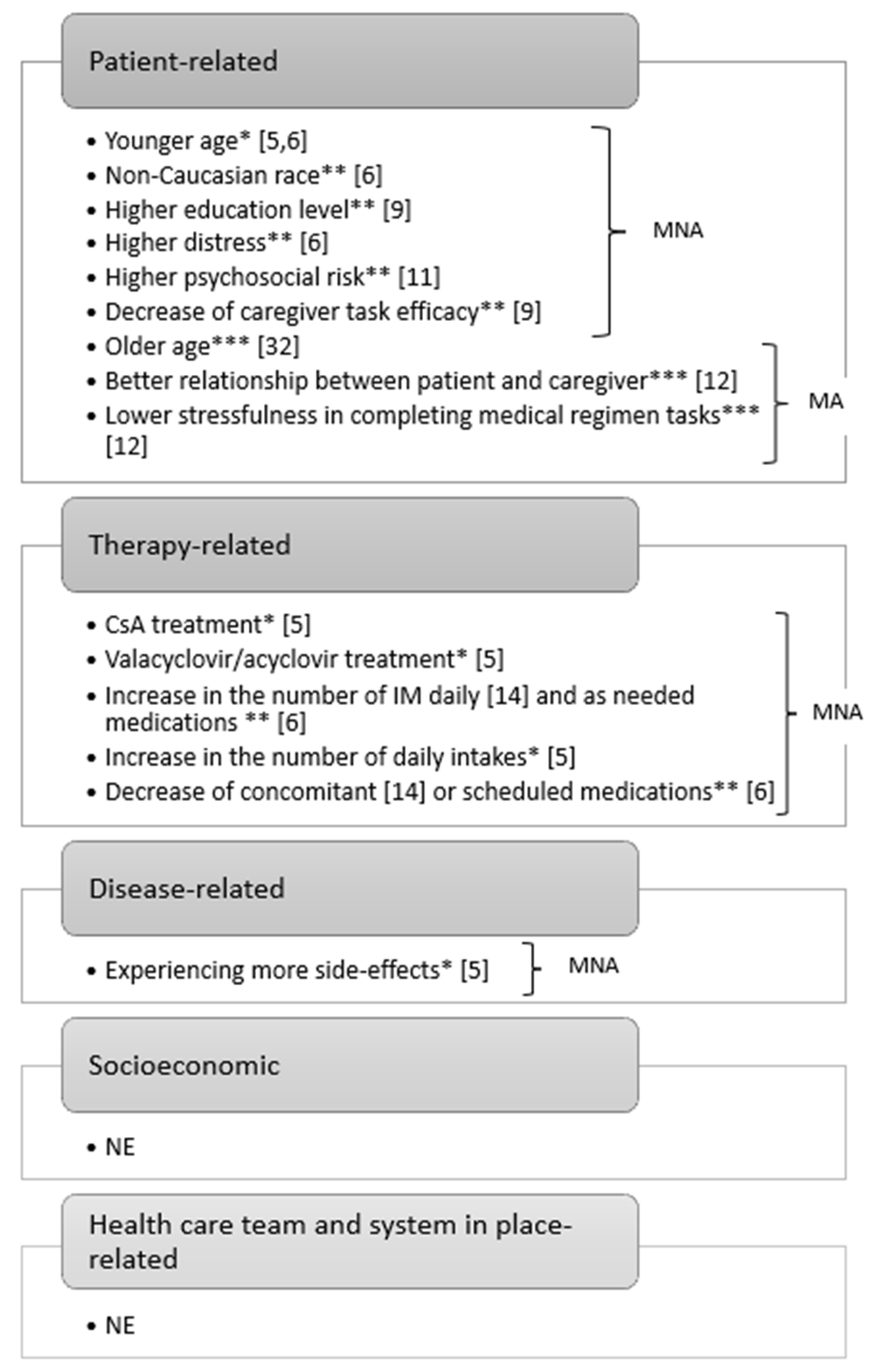

3.3. Factors Affecting MA/MNA

MNA Screening Tools

3.4. Interventions to Improve MA

3.5. Clinical Outcomes of MNA

4. Discussion

4.1. Oral MA: Assessment Tools and Rates

4.2. Factors Affecting MA/MNA and Screening Tools

4.3. Interventions to Improve MA

4.4. Clinical Outcomes of MNA

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Clinical level: we encourage the use of validated tools to assess MA longitudinally both for immunosuppressors and non-immunosuppressors by reporting findings in the clinical records, especially during the follow-up, and by involving caregivers as an integral part of the care process. Increasing awareness of these issues is important to address educational interventions, especially towards high-risk patients or those with MNA factors, e.g., young people.

- (2)

- Research level: it is necessary to use an MA framework and a multidimensional adherence measurement (subjective, objective, and biochemical), corroborating each measure with the others, in studies on MA. More emphasis should be given to validating MNA screening tools and on the multifactorial nature of MNA, considering also the socioeconomic-related and healthcare team and system-in-place-related factors. The role of caregivers’ and patients’ perceptions should also be considered. More attention should be devoted to MNA outcomes through prospective studies. In addition, when developing future MA tools, the threshold to define an adherent or a non-adherent patient should be based on outcomes.

- (3)

- Educational level: the MA topic should be addressed in undergraduate, postgraduate, and continuing education curricula, allowing an understanding of the differences in MA among HSCT, solid organ transplantation, and other chronic illnesses, by promoting multidisciplinary patient-centred care. Healthcare students at all levels should be aware of the role that they can play in the HSCT team. Adherence-related skills should be promoted and evaluated by also using peer education or simulation.

- (4)

- Management level: benchmarking adherence data across bone marrow centres must be encouraged, also to inform leaders in carrying out different models of care delivery, especially transitional care. Costs for adherence-enhancing interventions, including the effects of MNA such as GvHD treatment and readmissions, should be considered at the managerial level.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Snowden, J.A.; Sanchez-Ortega, I.; Corbacioglu, S.; Basak, G.W.; Chabannon, C.; de la Camara, R.; Dolstra, H.; Duarte, R.F.; Glass, B.; Greco, R.; et al. Indications for haematopoietic cell transplantation for haematological diseases, solid tumours and immune disorders: Current practice in Europe 2022. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2022, 57, 1217–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, F.R. Hematopoietic-Cell Transplantation at 50. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 1472–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, R.F.; Labopin, M.; Bader, P.; Basak, G.W.; Bonini, C.; Chabannon, C.; Corbacioglu, S.; Dreger, P.; Dufour, C.; Gennery, A.R.; et al. Indications for haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for haematological diseases, solid tumours and immune disorders: Current practice in Europe 2019. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019, 54, 1525–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passweg, J.R.; Baldomero, H.; Chabannon, C.; Corbacioglu, S.; de la Camara, R.; Dolstra, H.; Glass, B.; Greco, R.; Mohty, M.; Neven, B.; et al. Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on hematopoietic cell transplantation and cellular therapies in Europe 2020: A report from the EBMT activity survey. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2022, 57, 742–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaiche, S.; Décaudin, B.; Caron, A.; Depas, N.; Vignaux, C.; Vigouroux, S.; Coiteux, V.; Magro, L.; Sirvent, A.; Huynh, A.; et al. Medication non-adherence after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in adult and pediatric recipients: A cross sectional study conducted by the Francophone Society of Bone Marrow Transplantation and Cellular Therapy. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 35, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ice, L.L.; Bartoo, G.T.; McCullough, K.B.; Wolf, R.C.; Dierkhising, R.A.; Mara, K.C.; Jowsey-Gregoire, S.G.; Damlaj, M.; Litzow, M.R.; Merten, J.A. A Prospective Survey of Outpatient Medication Adherence in Adult Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Patients. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2020, 26, 1627–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charra, F.; Philippe, M.; Herledan, C.; Caffin, A.G.; Larbre, V.; Baudouin, A.; Schwiertz, V.; Vantard, N.; Labussiere-Wallet, H.; Ducastelle-Leprêtre, S.; et al. Immunosuppression medication adherence after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant: Impact of a specialized clinical pharmacy program. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Basas, L.; Sánchez-Cuervo, M.; de Salazar-López de Silanes, E.G.; Pueyo-López, C.; Núñez-Torrón-Stock, C.; Herrera-Puente, P. Evaluation of adherence and clinical outcomes in patients undergoing allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Farm. Hosp. 2020, 44, 87–91. [Google Scholar]

- Posluszny, D.M.; Bovbjerg, D.H.; Syrjala, K.L.; Agha, M.; Farah, R.; Hou, J.Z.; Raptis, A.; Im, A.P.; Dorritie, K.A.; Boyiadzis, M.M.; et al. Rates and Predictors of Nonadherence to the Post-Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Medical Regimen in Patients and Caregivers. Transplant. Cell Ther. 2022, 28, 165.e1–165.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoodin, F. Psychological and Behavioral Correlates of Medical Adherence among Adult Bone Marrow Transplant Recipients. Ph.D. Dissertation, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mishkin, A.D.; Shapiro, P.A.; Reshef, R.; Lopez-Pintado, S.; Mapara, M.Y. Standardized Semi-structured Psychosocial Evaluation before Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Predicts Patient Adherence to Post-Transplant Regimen. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019, 25, 2222–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posluszny, D.M.; Bovbjerg, D.H.; Agha, M.E.; Hou, J.Z.; Raptis, A.; Boyiadzis, M.M.; Dunbar-Jacob, J.; Schulz, R.; Dew, M.A. Patient and family caregiver dyadic adherence to the allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation medical regimen. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 354–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, C.F.; Martsolf, D.M.; Wehrkamp, N.; Tehan, R.; Pai, A.L.H. Medication Adherence in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: A Review of the Literature. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017, 23, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gresch, B.; Kirsch, M.; Fierz, K.; Halter, J.P.; Nair, G.; Denhaerynck, K.; De Geest, S. Medication nonadherence to immunosuppressants after adult allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A multicentre cross-sectional study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017, 52, 304–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, S.; Scheid, C.; von Bergwelt, M.; Hellmich, M.; Albus, C.; Vitinius, F. Psychosocial Pre-Transplant Screening With the Transplant Evaluation Rating Scale Contributes to Prediction of Survival After Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 741438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaté, E. Defining Adherence. In Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003; pp. 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M.T.; Bussell, J.K. Medication adherence: WHO cares? Mayo Clin. Proc. 2011, 86, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrijens, B.; De Geest, S.; Hughes, D.A.; Przemyslaw, K.; Demonceau, J.; Ruppar, T.; Dobbels, F.; Fargher, E.; Morrison, V.; Lewek, P.; et al. A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 73, 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaiche, S.; Decaudin, B.; Dharancy, S.; Noel, C.; Odou, P.; Hazzan, M. Factors relevant to medication non-adherence in kidney transplant: A systematic review. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2017, 39, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Nassetta, K.; O’Dwyer, L.C.; Wilcox, J.E.; Badawy, S.M. Adherence to immunosuppression in adult heart transplant recipients: A systematic review. Transplant. Rev. 2021, 35, 100651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokoel, S.R.M.; Gombert-Handoko, K.B.; Zwart, T.C.; van der Boog, P.J.M.; Moes, D.; de Fijter, J.W. Medication non-adherence after kidney transplantation: A critical appraisal and systematic review. Transplant. Rev. 2020, 34, 100511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, E.; Arber, A.; Gallagher, A. The Immediacy of Illness and Existential Crisis: Patients’ lived experience of under-going allogeneic stem cell transplantation for haematological malignancy. A phenomenological study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 21, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza-Zanetti, M.O.; Barboza-Zanetti, A.C.; Rodrigues-Abjaude, S.A.; Pinto-Simões, B.; Leira-Pereira, L.R. Clinical pharmacists’ contributions to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A systematic review. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2019, 25, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chieng, R.; Coutsouvelis, J.; Poole, S.; Dooley, M.J.; Booth, D.; Wei, A. Improving the transition of highly complex patients into the community: Impact of a pharmacist in an allogeneic stem cell transplant (SCT) outpatient clinic. Support Care Cancer 2013, 21, 3491–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polito, S.; Ho, L.; Pang, I.; Dara, C.; Viswabandya, A. Evaluation of a patient self-medication program in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2021, 28, 1790–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetti, M.O.B.; Rodrigues, J.P.V.; Varallo, F.R.; Cunha, R.L.G.; Simões, B.P.; Pereira, L.R.L. Can pharmacotherapeutic follow-up after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation improve medication compliance? J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2022, 29, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhubl, S.R.; Muse, E.D.; Topol, E.J. Can Mobile Health Technologies Transform Health Care? JAMA 2013, 310, 2395–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppla, L.; Hobelsberger, S.; Rockstein, D.; Werlitz, V.; Pschenitza, S.; Heidegger, P.; De Geest, S.; Valenta, S.; Teynor, A. Implementation Science Meets Software Development to Create eHealth Components for an Integrated Care Model for Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation Facilitated by eHealth: The SMILe Study as an Example. J. Nurs. Sch. 2020, 53, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppla, L.; Schmid, A.; Valenta, S.; Mielke, J.; Beckmann, S.; Ribaut, J.; Teynor, A.; Dobbels, F.; Duerinckx, N.; Zeiser, R.; et al. Development of an integrated model of care for allogeneic stem cell transplantation facilitated by eHealth-the SMILe study. Support Care Cancer 2021, 29, 8045–8057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribaut, J.; Leppla, L.; Teynor, A.; Valenta, S.; Dobbels, F.; Zullig, L.L.; De Geest, S. Theory-driven development of a medication adherence intervention delivered by eHealth and transplant team in allogeneic stem cell transplantation: The SMILe implementation science project. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Geest, S.; Valenta, S.; Ribaut, J.; Gerull, S.; Mielke, J.; Simon, M.; Bartakova, J.; Kaier, K.; Eckstein, J.; Leppla, L.; et al. The SMILe integrated care model in allogeneic SteM cell TransplantatIon faciLitated by eHealth: A protocol for a hybrid effectiveness-implementation randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehrer, J.; Brissot, E.; Ruggeri, A.; Dulery, R.; Vekhoff, A.; Battipaglia, G.; Giannotti, F.; Fernandez, C.; Mohty, M.; Antignac, M. Medication adherence among allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: A pilot single-center study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2018, 53, 231–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visintini, C.; Mansutti, I.; Palese, A. Medication adherence among allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: A systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e065676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. Chapter 1: JBI Systematic Reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2020; pp. 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harashima, S.; Yoneda, R.; Horie, T.; Fujioka, Y.; Nakamura, F.; Kurokawa, M.; Yoshiuchi, K. Psychosocial Assessment of Candidates for Transplantation scale (PACT) and survival after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019, 54, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, M.; Götz, A.; Halter, J.; Schanz, U.; Stussi, G.; Dobbels, F.; De Geest, S. Differences in health behaviours between survivors after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation and the general population: The provivo study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014, 49, S393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, U.S. Quality of Life following Bone Marrow Transplantation: A Comparison with a Matched-Group. Ph.D. Dissertation, The Graduate School, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tufanaru, C.; Munn, Z.; Aromataris, E.; Campbell, J.; Hopp, L. Chapter 3: Systematic Reviews of Effectiveness. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2020; pp. 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; et al. Chapter 7: Systematic Reviews of Etiology and Risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2020; pp. 255–257, 267–269. Available online: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/4687372/Chapter+7%3A+Systematic+reviews+of+etiology+and+risk (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Munn, Z.; Moola, S.; Lisy, K.; Riitano, D.; Tufanaru, C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and incidence data. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Oxman, A.D.; Vist, G.E.; Kunz, R.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Schünemann, H.J. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Br. Med. J. 2008, 336, 924–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Loberiza, F.R.; Antin, J.H.; Kirkpatrick, T.; Prokop, L.; Alyea, E.P.; Cutler, C.; Ho, V.T.; Richardson, P.G.; Schlossman, R.L.; et al. Routine screening for psychosocial distress following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005, 35, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, M.M.; Rodrigue, J.R.; Wingard, J.R. Mismanaging the gift of life: Noncompliance in the context of adult stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002, 29, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfield, S.; Clifford, S.; Eliasson, L.; Barber, N.; Willson, A. Suitability of measures of self-reported medication adherence for routine clinical use: A systematic review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passweg, J.R.; Baldomero, H.; Chabannon, C.; Basak, G.W.; de la Camara, R.; Corbacioglu, S.; Dolstra, H.; Duarte, R.; Glass, B.; Greco, R.; et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation and cellular therapy survey of the EBMT: Monitoring of activities and trends over 30 years. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2021, 56, 1651–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt Laederach-Hofmann, B.B. Noncompliance in Organ Transplant Recipients: A Literature Review. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2000, 22, 412–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, J.A.; Scheyer, R.D.; Mattson, R.H. Compliance declines between clinic visits. Arch. Intern. Med. 1990, 150, 1509–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmach, N.N.; Hamza, T.A.; Husen, A.A. Socioeconomic and Demographic Statuses as Determinants of Adherence to Antiretroviral Treatment in HIV Infected Patients: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Curr. HIV Res. 2019, 17, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Chen, S.; Roseman, J.; Scigliano, E.; Redd, W.H.; Stadler, G. It Takes a Team to Make It Through: The Role of Social Support for Survival and Self-Care After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 624906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, M.; Berben, L.; Johansson, E.; Calza, S.; Eeltink, C.; Stringer, J.; Liptrott, S.; De Geest, S. Nurses’ practice patterns in relation to adherence-enhancing interventions in stem cell transplant care: A survey from the Nurses Group of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2014, 23, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeneli, A.; Prati, S.; Golinucci, M.; Bragagni, M.; Montalti, S. L’inserimento degli infermieri specialisti nel contesto ambulatoriale di un centro di ricerca oncologico in Italia: Un’esperienza di introduzione del ruolo [Introducing clinical nurse specialists (CNS) in the ambulatory setting: The experience of a Research Cancer Center in Italy]. Assist. Inferm. Ric. 2021, 40, 194–204. [Google Scholar]

- Ribaut, J.; De Geest, S.; Leppla, L.; Gerull, S.; Teynor, A.; Valenta, S.; SMILe Study Team. Exploring Stem Cell Transplanted Patients’ Perspectives on Medication Self-Management and Electronic Monitoring Devices Measuring Medication Adherence: A Qualitative Sub-Study of the Swiss SMILe Implementation Science Project. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2022, 16, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Chen, S.; Roseman, J.; Scigliano, E.; Allegrante, J.P.; Stadler, G. Patient-generated strategies for strengthening adherence to multiple medication regimens after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: A qualitative study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2022, 57, 1455–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, R.N.; Becker, Y.; De Geest, S.; Eisen, H.; Ettenger, R.; Evans, R.; Rudow, D.L.; McKay, D.; Neu, A.; Nevins, T.; et al. Nonadherence consensus conference summary report. Am. J. Transplant. 2009, 9, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, G.B.; Sandmaier, B.M.; Mielcarek, M.; Sorror, M.; Pergam, S.A.; Cheng, G.S.; Hingorani, S.; Boeckh, M.; Flowers, M.D.; Lee, S.J.; et al. Survival, Nonrelapse Mortality, and Relapse-Related Mortality After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: Comparing 2003–2007 Versus 2013–2017 Cohorts. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 172, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoegy, D.; Bleyzac, N.; Robinson, P.; Bertrand, Y.; Dussart, C.; Janoly-Dumenil, A. Medication adherence in pediatric transplantation and assessment methods: A systematic review. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2019, 13, 705–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yussof, I.; Tahir, N.A.M.; Hatah, E.; Shah, N.M. Factors influencing five-year adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy in breast cancer patients: A systematic review. Breast 2022, 62, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tognoni, G. For a visibility of the subjects of health as a human right/common good. Assist. Inferm. Ric. 2021, 40, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

| Subjective (n = 13, 78.6% *) | Objective (n = 4, 35.7% *) | Biochemical (n = 2, 21.4% *) |

|---|---|---|

| BAASIS, validated [14] | Number of dispensation/refill records [6,8,24] | Drug serum level [6,7,8] |

| BAASIS in addition to physician evaluation [14] | Number of dose administration aids [24] | Number of serum assays [7] |

| BMQ, validated [26] | Pill counting [10] | |

| CET, validated and adapted [5] | Criteria based on an interdisciplinary team consensus [11] | |

| HHA, adapted [9,12] | ||

| ITAS, validated [6] | ||

| MMAS, validated [6,32] and modified [24] | ||

| MESI, validated [15] | ||

| Physician dichotomous evaluation based on drug serum levels [14] | ||

| VAS, validated [25] | ||

| 24-h recall [10] | ||

| Likert scale ** [15] | ||

| SRPA **, validated [10] |

| First Author, Year, Country | Prescribed Medication(s) Name, Frequency of Prescription among Population (n, %) | Outcomes Investigated | Main Results of the Study | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcomes Metric of the Tool Used to Screen MA/MNA, Prevalence Rate of Oral MA/MNA, Provider(s) and Timing of MA Measurement | Secondary Outcome 1 Factors Affecting MA and MNA as Predictor(s), Risk Factor(s), Facilitators/Barrier(s) and/or Screening Tool(s) of the Risk of MNA | Secondary Outcome 2 Intervention(s) to Improve MA, Timing of Provision and Provider(s) | Secondary Outcome 3 Incidence Rate of Infections, GvHD, Hospital Readmissions, Disease Relapse and/or Mortality and Time in Days from HSCT due to MNA | |||

| Cross-sectional studies | ||||||

| Belaiche et al., 2020 [5], France | Immunosuppressives: -CsA = 157 (84.4%) -Corticosteroids = 66 (35.5%) -FK = 9 (4.8%) -mTOR inhibitors = 9 (4.8%) Anti-infective prophylaxis: -Valacyclovir/acyclovir = 170 (86.7%) -Trimethoprim/atovaquone = 154 (78.6%) -Amoxicillin/oracillin = 153 (78.1%) Antiemetics/antinauseants = 39 (20.6%) | CET, a validated six-item self-report questionnaire (n = 192) CET, adapted self-report five-item questionnaire (n = 192) Good MA = 36 (18.8%), moderate MA = 139 (72.4%), poor MA = 17 (8.9%) (CET six item) 56% take medications later than the usual 67% think they have to take too many tablets and 9% admit forgetting to take medication some days Good MA = 82 (41.5%), moderate MA = 115 (57.5%), poor MA = 3 (1.5%) (CET five item) Patients and collected by the medical or paramedical team Once, during hospitalisation or medical visit | Univariate analysis: (CET six-item) -Age < 50 years (50.4 vs 55.1, p = 0.041) -Treatment with CsA (87.3% vs 69.0%, p = 0.023) and valacyclovir/acyclovir (89.6% vs 73.6%, p = 0.023) -Experiencing more side effects (46.3% vs 22.2%, p = 0.009) (CET five item) -Age < 50 years (49.8 vs 53.5, p = 0.049) -More intakes per day (3.7 vs 3.3, p = 0.049) Multivariate analysis: (CET six item) -Age (ß = −0.0095, p = 0.053) (CET five item) -Age (OR = 0.97, p = 0.041) | - | - | According to the six-item CET, 81.3% were non-adherent and 18.8% were adherent, while considering the five-item CET 5, 58.5% were non-adherent and 41.5% were adherent Age < 55 years was the only factor associated with NA that emerged from the multivariate analysis |

| Gresch et al., 2017 [14], Switzerland | Immunosuppressors: -Steroids = 11 (11.6%) -CsA or FK = 48 (50.5%) -mTOR inhibitor or mycophenolate) = 5 (5.3%) combination + steroids = 31 (32.6%) -Not documented = 4 (4.0%) Mean number of immunosuppressive pills = 2.5 (1–12) Mean number of concomitant medications = 8.0 (1–22) | BAASIS, a validated six-item self-report questionnaire Physician dichotomous evaluation based on drug serum levels BAASIS scores combined with physicians’ evaluation MNA = 64 (64.6%): 33 (33.3%) had missed at least one dose 3 (3.2%) had missed at least two consecutive doses (‘drug holidays’) 61 (61.2%) had timing NMA (2 h too early or too late) 4 (4.1%) had themselves reduced the dosages 3 (3.1%) stopped the treatment early (non-persistent with therapy) MNA = 18 (18.9%) MNA = 68 (68.7%) Patients for self-report Laboratory A senior physician NR | Univariate analysis: -Number of daily taken immunosuppressive pills: OR 1.33 (95% CI 1.04–1.69, p = 0.022) -Calcineurin inhibitors (CsA or FK) only: OR 5.513 (95% CI 1.17–25.86, p = 0.030) -Combination of immunosuppressors and steroids: OR 8.56 (95% CI 1.62–45.16, p = 0.011) -Number of daily taken concomitant medications: OR 0.87 (95% CI 0.77–0.99, p = 0.035) Multivariate analysis: -Higher number of daily taken immunosuppressive pills: OR 1.42 (95% CI 1.08–1.87, p = 0.011) -Lower number of daily prescribed concomitant medications: OR 0.85 (95% CI 0.74–0.98, p = 0.024) | - | Higher grades of cGvHD correlate with MNA: OR 3.01 (95% CI 1.27–7.14, p = 0.012) -No/mild cGvHD = 62.2% among adherent patients -Moderate/severe cGvHD = 80.2% among non-adherent patients | This is the first study to describe an association between cGvHD and MNA. A high prevalence of MNA was shown, particularly regarding timing and taking Surprisingly, patients taking a higher number of immunosuppressive agents as well as patients taking a lower number of concomitant medications were more likely to be non-adherent |

| Ice et al., 2020 [6], USA | Non-immunosuppressors = 200 (100.0%) Oral immunosuppressors (CsA, FK, sirolimus, prednisone, mycophenolate) = 153 (76.5%) Mean number of medications = 17 (3–42) Mean number of scheduled medications = 12 (1–29) Mean number of as-needed medications = 5 (0–19) | MMAS, a validated eight-item self-report questionnaire for non-immunosuppressors ITAS, self-report nine-item questionnaire validated in the kidney transplantation context for immunosuppressors Immunosuppressor serum drug levels (n = 29, 14.5%) Prescription refill records for immunosuppressors (1 − ([days between refills − total supply in days]/days between refills) × 100% (n = 15, 75.0%) High MA = 98 (48.0%) MNA = 102 (51.0%, 95% CI 44.1–57.9%) (MMAS) High MA = 95 (62.1%) MNA = 58 (37.9%, 95% CI 30.2–45.6%) (ITAS) No differences in MNA regarding drug monitoring (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.94–1.02, p = 0.25) No differences in NMA regarding prescription refill records (r = −0.3015, p = 0.27) Patients and collected by nurses during clinical appointments and medical records Laboratory NR for the questionnaires, serum drug levels and prescription refill records collected for the previous 3 months | Univariate analysis: (MMAS) -Younger age (55.5 vs 57 years, p = 0.009) Multivariate analysis: (MMAS) -Older age (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.94–0.99, p = 0.016) -Severe distress (OR 1.15, 95% CI 1.01–1.31, p = 0.035) using the Distress Thermometer, a validated tool -Higher number of as-needed medications (OR 1.14, 95% CI 1.03–1.27, p = 0.013) -Increased number of scheduled medications (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.86–0.998, p = 0.043) (ITAS) -Distress (OR 1.17, 95% CI 1.02–1.34, p = 0.026) -Non-Caucasian race (OR 8.86, 95% CI 0.94–83.5, p = 0.057) | - | cGvHD (based on the ITAS) = 161 (80.5%) -Mild = 49 (24.5%) (OR 2.63, 95% CI 1.04–6.66, p = 0.042) -Moderate = 74 (37.0%) -Severe = 38 (19.0%) Mortality based on the MMAS = HR 1.43, 95% CI 0.83–2.44, p = 0.19; based on the ITAS = HR 1.33, 95% CI 0.72–2.44, p = 0.36. Due to: -GvHD (n = 16) -Relapse (n = 12) -Infection (n = 9) -Multiorgan failure (n = 5) -Unknown (n = 5) -Secondary malignancy (n = 4) -Cardiovascular disease (n = 3) | MNA to immunosuppressors was associated with mild cGvHD Moreover, MNA was found to be highly prevalent for both immunosuppressors and non-immunosuppressors |

| Mishkin et al., 2018 [11], USA | NR | Criteria for life-threatening NA based on a consensus by an interdisciplinary team, based on evidence from solid organ transplantation NA = 18 (21.0%) * NA among allogeneic (n = 42) = 13 (30.9%) Interdisciplinary team (five HSCT clinicians, namely physician assistants, nurse managers, social workers and oncologists) Electronic medical records after discharge | Univariate analysis: -Higher SIPAT, a validated psychosocial assessment tool: OR 1.162 (p < 0.001) Multivariate analysis: -Higher SIPAT: RR 4.98 (p < 0.0001) -Allogeneic HSCT: OR 14.184 (p = 0.005) | - | No association between adherence and survival [11] | A cut-off score of 18 provided optimal specificity (89.6%) and sensitivity (55.6%) for NA with SIPAT NA rates were 58.8% and 11.8% for subjects with SIPAT ratings of ≥ 18 or < 17, respectively (RR 4.98, p < 0.0001) Psychosocial risk as quantified by the SIPAT correlated with adherence to the post-transplant regimen. Moreover, high-risk SIPAT patients (OR 11.679, p = 0.002) and allogeneic respect to autologous (OR 6.867, p = 0.034) had an increased risk of being admitted to the ICU However, no correlation between SIPAT score or NA and morbidity, readmissions or mortality |

| Posluszny et al., 2018 [12], USA | Immunosuppressors twice/daily (NR) Non-immunosuppressors daily (NR) | Adapted version of the 16-item HHA (two items related to oral MA), a validated self-report assessment tool for both patients and caregivers Modified version of the item ‘Who was mostly responsible for this task being accomplished?’ from the Family Responsibility Questionnaire MA to immunosuppressors = 15 (71.4%) (90% among patients mostly responsible vs 50.0% among caregivers mostly responsible or shared responsibility, p = 0.063) MA to non-immunosuppressors = 16 (71.4%) (100% among patients mostly responsible vs 45.0% among caregivers mostly responsible or shared responsibility, p = 0.012) Dyads of patients and caregivers for self-report During follow-up | Immunosuppressors: -Better relationship quality as reported by the patients on the six-item QMI (r = 0.52, p = 0.015) -Less perceived stressfulness of the medical regimen on a dichotomous item from Lee et al. [43], by both the patients (r = −0.45, p = 0.042) and the caregivers (r = −0.57, p = 0.011) Non-immunosuppressors: -Less perceived stressfulness of the medication regimen by the caregivers (r = −0.46, p = 0.048) | - | - | Although adherence to attending medical appointments was 100%, adherence to all other tasks was not optimal Immunosuppressor MA was 71%; perceived regimen stressfulness appeared to be a more important factor than distress (depression and anxiety) in relation to medication taking Adherence levels for some tasks were influenced by which member of the dyad took responsibility for its accomplishment. Thus, strategies to improve adherence should consider dyadic factors including division of task responsibility |

| Quasi-experimental studies | ||||||

| Charra et al., 2021 [7], France | Immunosuppressives: CsA = 22 (84.6%) FK = 4 (15.4%) (intervention group) CsA = 32 (91.4%) FK = 3 (8.6%) (control group) | Immunosuppressor drug serum levels in the therapeutic target range Number of serum assays MA = 61.5% (intervention group) vs 53.0% (control group) (p = 0.07) Mean number of serum assays = 11.5 (intervention group) vs 10.9 (control group) (p = 0.46) until 100 days post-HSCT or until immunosuppressor tapering Immunology laboratory Day care follow-up | - | Prospective cohort (n = 26): 79 pharmaceutical consultations (median, 3 per patient) -The day before discharge consisting of proactive medication reconciliation, personalised medication intake schedule, patient education and contact with community pharmacy (mean duration of 25 min) -During weeks 2 and 4 after discharge from the HSCT unit and once a month until day 100 post-HSCT, consisting of pharmaco-therapeutic analysis of prescriptions, review of medication with patient, identification of drug related problems at home, patient education (mean duration of 16 min) Retrospective cohort (n = 39): no pharmaceutical consultations, standard patient follow-up (not better specified) | - | Implementation of a specialised clinical pharmacy programme for patients who have received allogeneic HSCT seems to be beneficial for immunosuppressor adherence However, there were no significant differences with respect to aGvHD, infections and hospital readmission rates |

| Chieng et al., 2013 [24], Australia | Antiemetics (NR) Azole antifungals (NR) Ganciclovir (NR) Immunosuppressors (NR) Prophylactic antibiotics: -Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (NR) -Phenoxymethylpenicillin (NR) Ursodeoxycholic acid (NR) | Adapted MMAS score, four-item questionnaire Number of dose administration aids Number of dispensation records Mean decrease of 1.53 points on the MMAS (95% CI 1.12–1.94, p < 0.0001) with score 0 (adherence = 100.0%) at the sixth visit (n = 17) Accurate use of aids and dispensation records Patients for self-report Clinical pharmacist Pharmacy dispensing system Weekly during each ambulatory visit from the second week post-discharge | - | Six weekly consultations (mean duration of 20 min, the first at week 2 post-discharge and the other within 7–10 days) by a clinical pharmacist with postgraduate qualification in clinical pharmacy and extensive experience in cancer care At every visit (n = 109), medication reconciliation interviews (n = 161, 1.4 per patient visit) were recorded and blindly assigned a risk rating by a multidisciplinary panel, considering the potential impact if the intervention had not occurred in combination with the likelihood of having to intervene in the same drug-problem in the future | - | 40% of interventions were rated as high risk, 46% as medium risk and 14% as low risk; high- and medium-risk interventions constituted > 80% of the total MMAS scores improved by an average of 1.53 points (p < 0.0001) and all the patients were scored as highly adherent by the last visit |

| Polito et al., 2021 [25], Canada | NR | VAS MA = median 100% in both groups, interquartile range = 0 (intervention group) vs interquartile range = 5 (comparison group) (p = 0.12) Patients for self-report At a follow-up appointment 3–5 weeks post-discharge | - | Intervention group (SMP, n = 25): provision of medication counselling and medication charts by a pharmacist during the hospital stay at a time determined by the interprofessional health care team and supervision of patients’ self-administration of medications in a way similar to how it would be dispensed from a retail pharmacy by a nurse, who verifies the dose and documents that the dose has been taken by signing off on patient’s eMAR until discharge from HSCT unit Comparison group (n = 26): provision of a detailed one-on-one medication counselling session performed by a pharmacist within 24 h before discharge from the HSCT unit and of a personalised medication chart detailing the discharge medication schedule | - | Median knowledge scores in the comparison group vs the SMP group were 8.5/10 vs 10/10 at discharge (p = 0.0023) and 9/10 vs 10/10 at follow-up (p = 0.047). Differently, median self-efficacy scores at both discharge and follow-up were no significantly different (p discharge = 0.11, p follow-up = 0.10) The SMP did not result in a significant difference even in self-reported MA. However, the SMP was associated with at least 1 medication event in 7 participants, but no medication incidents occurred Patient and staff surveys showed a positive perceived value of the SMP |

| Zanetti et al., 2022 [26], Brazil | NR | BMQ, a validated 11-item self-report questionnaire for antihypertensive drugs Compliance (n = 27): 11 (40.74%) before medication advice and educational activities vs 19 (70.37%) until the end of the follow-up period (p = 0.0115) Compliance (n = 18 adults): 7 (38.9%) before medication advice and educational activities vs NR until the end of the follow-up period Patients self-report collected by pharmacist Before medication advice and educational activities and until the end of the follow-up period | No factors (age, gender, schooling, occupation, marital status, income, type of HSCT, source of stem cells, health problems or comorbidities) among the investigated before the first consultation (p > 0.05) | Pharmaceuticals consultations by a clinical pharmacist (n = 390) in the -Inpatient setting (from admission to discharge): daily pharmacotherapy review (analysis of the prescriptions, laboratory tests and patient’s clinical evolution, aiming at the prevention, monitoring, detection and resolution of DRPs (n = 278, 89.97%), production of educational materials on the use of medications for the health team, medication reconciliation at admission and discharge, discussion of discharge prescription and participation in the daily clinical team meetings -Outpatient setting (n = 130, 4.81 ± 1.80 per patient, lasting nearly 20 min): weekly pharmaceutical consultations consisting of pharmacotherapy review (n = 31, 10.30%), production of educational materials for the patient (using pictograms, medication organisers and booklets, guidelines on the use and storage of the medications) and other educational activities and participation in the clinical team meetings | Number of hospital readmissions at 100 days post-HSCT: χ2 = 7.816 (p = 0.021) GvHD: χ2 = 0.622 (p = 0.633) Transplant-related mortality: 0 (-) | Pharmacotherapeutic follow-up contributed to improve medication compliance (p = 0.0115) No relation between knowledge and compliance scores (p = 0.438) at the last consultation; thus, knowledge about pharmacotherapy alone does not translate into behaviours, which corroborates the complexity of the biopsychosocial factors associated with medication compliance |

| Correlational study | ||||||

| Hoodin, 1993 [10], USA | NR | Number of medication infractions using the 24-hour recall method, a validated self-report method Pill counting Mean MA is the same among the three repeated measures (94.7% ± 7.8): F (2, 45) = 4.480, p = 0.017 -3.8–6.5% taking over-dose -8.3–11.1% taking under-dose -14.3–18.0% taking more of at least one dose -30.0–35.7% taking less of at least one dose MNA among allogeneic (n = 41) ≈ 7% Pill counting corroborated a mean of 67% (at second occasion) and 73% (at third occasion) Patients collected from staff during ambulatory visit and by telephone On three occasions between 84 and 100 days post-HSCT | None of the pre-HSCT predictors of affective distress were significant. Multivariate analysis: -Allogeneic (R2 = 0.145, F (5, 48) = 1.627, p = 0.171): ß = −0.303, t = −2.257, p = 0.029 -Self-reported pre-HSCT adherence based on SRPA, a validated nine-item self-report questionnaire (R2 = 0.145, F (5, 48) = 1.627, p = 0.171): ß = −0.083, t = 0.586, p = 0.561 | - | - | Rate of mean hygiene adherence (65.2% ± 16.6%) was significantly worse than MA (94.7% ± 7.8%) or environmental restrictions (93.7% ± 6.9%) (p < 0.001), with autologous transplant patients committing more infractions than allogeneic recipients, despite their simpler medication regimen (p = 0.02) None of the demographic or psychological variables predicted medication or hygiene adherence. However, total inpatient days predicted hygiene adherence (p < 0.01) These findings indicate that although adherence is quite high to complex medication regimens and environmental restrictions, hygiene adherence is a significant problem, particularly for autologous patients |

| Cohort studies | ||||||

| Scherer et al., 2021 [15], Germany | Immunosuppressors (NR) | MESI, a validated seven-item self-report questionnaire at 3, 12 and 36 months after HSCT A 5-point Likert scale, not validated before HSCT (n = 61) MA = 17 (40.5%), 3 months after HSCT (n = 42) MA = 14 (53.9%) 12 months after HSCT (n = 26) MA = 7 (50.0%) 36 months after HSCT (n = 14) Patients for self-report Before transplantation, at 3, 12 and 36 months after HSCT | TERS, a validated 10-item questionnaire: -Correlates with pre-HSCT MA assessed by clinicians on a 5-item Likert scale (mean score = 2, r = 0.36, p = 0.011) (n = 61) -Does not correlate with MESI, in the inpatient (p = 0.85, r = −0.026, 3 months after HSCT, p = 0.12, r = −0.206, 12 months after HSCT) and outpatient (p = 0.96, r = 0.009, 3 months after HSCT, p = 0.9, r = 0.03 12 months after HSCT) settings | - | - | Two groups emerged from the TERS score: the low-risk (26.5–29.0) and the increased-risk (29.5–79.5) groups. The increased-risk group showed significantly worse cumulative survival in the outpatient setting (log rank [Mantel Cox] p = 0.029] compared with the low-risk group, but there was no significant result for the interval immediately until 3 years after HSCT Pre-transplant screening with TERS contributes to predict survival after HSCT. The reason remains unclear because TERS scores did not correlate with GvHD or MESI |

| Posluszny et al., 2022 [9], USA | Immunosuppressors twice/daily (NR) Non-immunosuppressors daily (NR) | A modified version of the 17-item HHA (two items related to oral MA), a validated self-report assessment tool for both patients and caregivers (a single measure for each item was determined by comparing the responses of each member’s dyad) MNA to immunosuppressors = 10 (11.2%) at week 4 after discharge (n = 89) and 14 (15.7%) at week 8 after discharge (n = 84) MNA to non-immunosuppressors = 31 (34.8%) at week 4 after discharge (n = 89) and 33 (38.6%) at week 8 after discharge (n = 84) Patients and caregivers interviewed by a trained interviewer At week 4 and week 8 after discharge | Multivariate analysis: At 4 weeks post-discharge: (based on an adaptation of a tool validated in the heart disease population) -Lower caregiver task efficacy (F (8, 527), p = 0.004): b = −0.30, p < 0.01 At 8 weeks post-discharge: -Higher patients’ education level (F (5, 440), p = 0.002): b = 0.32, p < 0.01 | - | - | NA rates varied among tasks, with 11.2–15.7% of the sample reporting MNA to immunosuppressors, 34.8–38.6% to other types of medications, 14.6–67.4% to required infection precautions, and 27.0–68.5% to lifestyle-related behaviours (as diet/exercise) NA rates were generally stable but worsened over time for lifestyle-related behaviours; the most consistent predictors were patient and caregiver pre-HSCT perceptions of lower HSCT task efficacy Higher caregiver depression, caregiver perceptions of poorer relationship with the patient, having a non-spousal caregiver, and diseases other than AML also predicted greater NA in one or more areas |

| Studies reporting prevalence data | ||||||

| García-Basas et al., 2020 [8], Spain | Immunosuppressors (n = 46): -CsA = 46 (100.0%) -FK = 1 (2.2%) -Sirolimus = 3 (6.5%) -Mycophenolate = 34 (73.9%) Anti-infection prophylaxis (n = 19): -Antifungal (n = 13, 28.3%): -Posaconazole = 8 (61.5%) -Voriconazole = 4 (30.8%) -Posaconazole + voriconazole = 1 (7.7%) Antiviral with valganciclovir = 10 (21.7%) | Mean of dispensation records Reports on amounts of medication dispensed at different dates for mycophenolate, FK, sirolimus, posaconazole, voriconazole and valganciclovir CsA, FK and sirolimus serum level in the therapeutic range MA to immunosuppressors against secondary graft failure = 38 (82.6%) CsA = 39 (84.8%) Sirolimus = 3 (100.0%) MA to immunosuppressors against GvHD = 37 (80.4%) CsA = 39 (84.8%) Sirolimus = 3 (100.0%) Mycophenolate = 29 (84.2%) MA to anti-infection prophylaxis = 46 (100.0%) Pharmacy department Community pharmacy NR | - | - | Secondary graft failure: 0 (-) aGvHD = 17 (45.9%) in adherent patients vs 5 (55.6%) in non-adherence patients: OR 0.68 (95% CI 0.157–2.943, p = 0.718) Infections = 31 (67.4%) Readmission rates among adherent patients due to: -aGvHD (18.0%) -Infections (75.0%) | Acceptable adherence to prophylaxis has been seen against acute complications, although a considerable percentage of patients did not to take their medication as prescribed Correct adherence to immunosuppressors seems to reduce the risk of developing aGvHD |

| Lehrer et al., 2018 [32], France | CsA = 29 (87.9%) NR Mean number of prescribed drugs = 12 | MMAS, a validated eight-item self-report questionnaire Poorly adherent = 18 (54.6%) Low MA = 2 (6.1%) Medium MA = 16 (48.5%) Highly adherent = 15 (45.4%) Patients NR | MA increased as age increased (ρ = 0.47, p = 0.03) | - | No association between MA and GvHD (26.7% vs 38.9%, p = 0.71) | More than half (54.6%) of patients were poorly adherent to medication The authors suggest that younger patients have poorer adherence than older patients |

| Author, Year | Aims Related to MA | Population | Intervention(s) | Rates and Measures of MA | Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charra et al., 2021 [7] | To evaluate the impact of a specialised clinical pharmacy programme on adherence to oral immunosuppression treatment after discharge from the HSCT unit | n = 61 total n = 26 (42.6%) intervention group n = 35 (57.4%) control group | Prospective cohort (n = 26): 79 pharmaceutical consultations (median of 3 per patient) - The day before discharge (proactive medication reconciliation, personalised medication intakes schedule, patient education, contact with community pharmacy; mean duration of 25 min) - During weeks 2 and 4 post-discharge and once a month until day 100 post-HSCT (pharmacotherapeutic analysis of prescriptions, review of medication with the patient, identification of drug-related problems at home, patient education; mean duration of 16 min) Retrospective cohort (n = 39): no pharmaceutical consultations, standard patient follow-up (not specified further) | Drug serum levels in the therapeutic target range: 61.5% (intervention group) vs 53.0% (control group) (p = 0.07) Mean number of serum assays: 11.5 (intervention group) vs 10.9 (control group) (p = 0.46) | ↕ |

| Chieng et al., 2013 [24] | To evaluate the effectiveness of a specialty clinical pharmacist working in an ambulatory stem cell transplant clinic | n = 23 | Six weekly consultations (the first at week 2 post-discharge and the other within 7–10 days; mean duration of 20 min) by a clinical pharmacist with a postgraduate qualification in clinical pharmacy and extensive experience in cancer care | Mean decrease of 1.53 points on MMAS (95% CI 1.12–1.94, p < 0.0001) with score 0 at the sixth visit (n = 17) Accurate use of dose administration aids and dispensation records | ↑ |

| Polito et al., 2021 [25] | To assess the impact of a self-medication programme on adherence | n = 51 total n = 25 (49.0%) (intervention group) n = 26 (51.0%) (comparison group) | Intervention group (n = 25): provision of medication counselling and medication charts by a pharmacist during the hospital stay and supervision of patients’ self-administration of medications by a nurse, who documents the taken dose by signing off on the patient’s eMAR until discharge Comparison group (n = 26): provision of a detailed one-on-one medication counselling session performed by a pharmacist within 24 h before discharge and of a personalised medication chart detailing the discharge medication schedule | Median 100% based on the VAS, interquartile range = 0 (intervention group) vs 5 (comparison group) (p = 0.12) | ↕ |

| Zanetti et al., 2022 [26] | To evaluate the results of pharmacotherapeutic follow-up on medication compliance and on the patients’ knowledge about pharmacotherapy | n = 27 total n = 18 (66.7%) adults n = 9 (33.3%) children | Pharmaceuticals consultations conducted by a clinical pharmacist (n = 390) in: - Inpatient setting (from admission to discharge): daily pharmacotherapy review (analysis of the prescriptions, laboratory tests and patient’s clinical evolution, aiming at the prevention, monitoring, detection and resolution of DRPs), production of educational materials on the use of medications for the health team, medication reconciliation at admission and discharge, discussion of discharge prescription and participation in the daily clinical team meetings - Outpatient setting (n = 130, 4.81 ± 1.80 per patient, lasting nearly 20 min): weekly pharmaceutical consultations consisting of pharmacotherapy review (prevention, monitoring, detection and resolution of DRPs), production of educational materials for the patient (using pictograms, medication organisers and booklets and guidelines on the use and storage of the medications) and other educational activities, participation in the clinical team’s meetings | 11 (40.74%) based on the BMQ (before medication advice and educational activities) vs 19 (70.37%) (at the last consultation) (p = 0.0115) (n = 27) 7 (38.9%) based on the BMQ (before the first consultation) vs NR (for the last consultation) (n = 18 adults) | ↑ but NR for the adult population |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Visintini, C.; Mansutti, I.; Palese, A. Medication Adherence among Allogeneic Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2023, 15, 2452. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15092452

Visintini C, Mansutti I, Palese A. Medication Adherence among Allogeneic Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients: A Systematic Review. Cancers. 2023; 15(9):2452. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15092452

Chicago/Turabian StyleVisintini, Chiara, Irene Mansutti, and Alvisa Palese. 2023. "Medication Adherence among Allogeneic Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients: A Systematic Review" Cancers 15, no. 9: 2452. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15092452

APA StyleVisintini, C., Mansutti, I., & Palese, A. (2023). Medication Adherence among Allogeneic Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients: A Systematic Review. Cancers, 15(9), 2452. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15092452