Young Adult German Breast Cancer Patients Participating in a Three-Week Inpatient Mother–Child Rehab Program Have High Needs for Supportive Care

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cohort Study in the Context of the Rehab Program “Get Well Together”

2.2. Quality of Life

2.3. Need for Supportive Care

2.4. Clinical Characteristics, Treatment, and Socio-Demographics

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

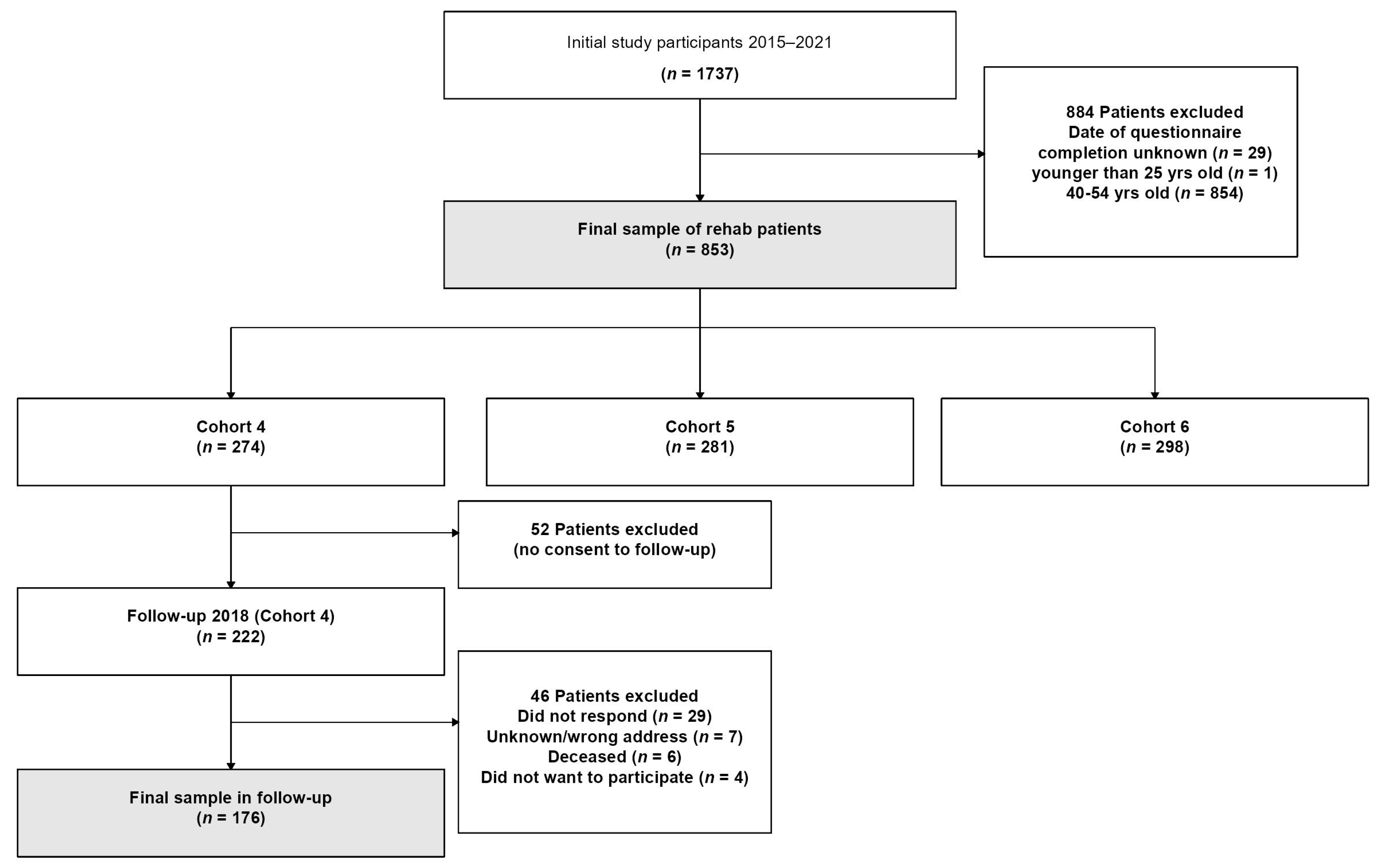

3.1. Sample Selecetion

3.2. Sample Description

3.3. Clinical Characteristics and Cancer Treatment

3.4. Need for Supportive Care

3.5. Quality of Life and Need for Supportive Care during the Rehab Stay and Three Years Later

4. Discussion

4.1. Need for Supportive Care

4.2. Need for Supportive Care and Changes Associated with the COVID-19 Pandemic (Cross-Sectional Data)

4.3. Proportion with Need for Supportive Care at Baseline and Follow-Up (Longitudinal Data)

4.4. Practical Implications for Provision of Supportive Care

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koch-Institut und die Gesellschaft der Epidemiologischen Krebsregister in Deutschland e.V. Krebs in Deutschland Fuer 2017/2018. 13. Ausgabe; Robert Koch-Institut: Berlin, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Geue, K.; Sender, A.; Schmidt, R.; Richter, D.; Hinz, A.; Schulte, T.; Brähler, E.; Stöbel-Richter, Y. Gender-specific quality of life after cancer in young adulthood: A comparison with the general population. Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zentrum für Krebsregisterdaten am Robert Koch-Institut. Datenbankabfrage, Datenstand September 2022. Available online: https://www.krebsdaten.de/Krebs/DE/Datenbankabfrage/datenbankabfrage_stufe1_node.html (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- Cardoso, F.; Loibl, S.; Pagani, O.; Graziottin, A.; Panizza, P.; Martincich, L.; Gentilini, O.; Peccatori, F.; Fourquet, A.; Delaloge, S.; et al. The European Society of Breast Cancer Specialists recommendations for the management of young women with breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2012, 48, 3355–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banz-Jansen, C.; Heinrichs, A.; Hedderich, M.; Waldmann, A.; Wedel, B.; Mebes, I.; Diedrich, K.; Rody, A.; Fischer, D. Are there changes in characteristics and therapy of young patients with early-onset breast cancer in Germany over the last decade? Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2013, 288, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cathcart-Rake, E.J.; Ruddy, K.J.; Bleyer, A.; Johnson, R.H. Breast Cancer in Adolescent and Young Adult Women under the Age of 40 Years. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2021, 17, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, B.L.; Day, C.N.; Hoskin, T.L.; Habermann, E.B.; Boughey, J.C. Adolescents and Young Adults with Breast Cancer have More Aggressive Disease and Treatment than Patients in Their Forties. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 26, 3920–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Huang, W.; Ji, F.; Pan, Y.; Yang, L. Comparisons of Metastatic Patterns, Survival Outcomes and Tumor Immune Microenvironment Between Young and Non-Young Breast Cancer Patients. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 923371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, V.L.; Wagner, L.I.; Monahan, P.O.; Daggy, J.; Smith, L.; Cohee, A.; Ziner, K.W.; Haase, J.E.; Miller, K.D.; Pradhan, K.; et al. Comparison of younger and older breast cancer survivors and age-matched controls on specific and overall quality of life domains. Cancer 2014, 120, 2237–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammersen, F.; Pursche, T.; Fischer, D.; Katalinic, A.; Waldmann, A. Psychosocial and family-centered support among breast cancer patients with dependent children. Psycho-Oncology 2021, 30, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernstmann, N.; Neumann, M.; Ommen, O.; Galushko, M.; Wirtz, M.; Voltz, R.; Hallek, M.; Pfaff, H. Determinants and implications of cancer patients’ psychosocial needs. Support. Care Cancer 2009, 17, 1417–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bultmann, J.C.; Beierlein, V.; Romer, G.; Moller, B.; Koch, U.; Bergelt, C. Parental cancer: Health-related quality of life and current psychosocial support needs of cancer survivors and their children. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 135, 2668–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgkinson, K.; Butow, P.; Hunt, G.E.; Pendlebury, S.; Hobbs, K.M.; Wain, G. Breast cancer survivors’ supportive care needs 2–10 years after diagnosis. Support. Care Cancer 2007, 15, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehnert, A.; Koch, U. Psychological comorbidity and health-related quality of life and its association with awareness, utilization, and need for psychosocial support in a cancer register-based sample of long-term breast cancer survivors. J. Psychosom. Res. 2008, 64, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aaronson, N.K.; Ahmedzai, S.; Bergman, B.; Bullinger, M.; Cull, A.; Duez, N.J.; Filiberti, A.; Flechtner, H.; Fleishman, S.B.; de Haes, J.C.; et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1993, 85, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osoba, D.; Rodrigues, G.; Myles, J.; Zee, B.; Pater, J. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 1998, 16, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocks, K.; King, M.T.; Velikova, G.; de Castro, G., Jr.; Martyn St-James, M.; Fayers, P.M.; Brown, J.M. Evidence-based guidelines for interpreting change scores for the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30. Eur. J. Cancer 2012, 48, 1713–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giesinger, J.M.; Loth, F.L.C.; Aaronson, N.K.; Arraras, J.I.; Caocci, G.; Efficace, F.; Groenvold, M.; van Leeuwen, M.; Petersen, M.A.; Ramage, J.; et al. Thresholds for clinical importance were established to improve interpretation of the EORTC QLQ-C30 in clinical practice and research. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 118, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musoro, J.Z.; Coens, C.; Fiteni, F.; Katarzyna, P.; Cardoso, F.; Russell, N.S.; King, M.T.; Cocks, K.; Sprangers, M.A.; Groenvold, M.; et al. Minimally Important Differences for Interpreting EORTC QLQ-C30 Scores in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2019, 3, pkz037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.F.; Blackford, A.L.; Brahmer, J.R.; Carducci, M.A.; Pili, R.; Stearns, V.; Wolff, A.C.; Dy, S.M.; Wu, A.W. Needs assessments can identify scores on HRQOL questionnaires that represent problems for patients: An illustration with the Supportive Care Needs Survey and the QLQ-C30. Qual. Life Res. 2010, 19, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.F.; Blackford, A.L.; Okuyama, T.; Akechi, T.; Yamashita, H.; Toyama, T.; Carducci, M.A.; Wu, A.W. Using the EORTC-QLQ-C30 in clinical practice for patient management: Identifying scores requiring a clinician’s attention. Qual. Life Res. 2013, 22, 2685–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidington, E.; Giesinger, J.M.; Janssen, S.H.M.; Tang, S.; Beardsworth, S.; Darlington, A.S.; Starling, N.; Szucs, Z.; Gonzalez, M.; Sharma, A.; et al. Identifying health-related quality of life cut-off scores that indicate the need for supportive care in young adults with cancer. Qual. Life Res. 2022, 31, 2717–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beese, F.; Waldhauer, J.; Wollgast, L.; Pfortner, T.K.; Wahrendorf, M.; Haller, S.; Hoebel, J.; Wachtler, B. Temporal Dynamics of Socioeconomic Inequalities in COVID-19 Outcomes over the Course of the Pandemic-A Scoping Review. Int. J. Public Health 2022, 67, 1605128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grasso, M.; Klicperová-Baker, M.; Koos, S.; Kosyakova, Y.; Petrillo, A.; Vlase, I. The impact of the coronavirus crisis on European societies. What have we learnt and where do we go from here?-Introduction to the COVID volume. Eur. Soc. 2021, 23, S2–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventriglio, A.; Castaldelli-Maia, J.M.; Torales, J.; Chumakov, E.M.; Bhugra, D. Personal and social changes in the time of COVID-19. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2021, 38, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benatov, J.; Ochnik, D.; Rogowska, A.M.; Arzenšek, A.; Mars Bitenc, U. Prevalence and Sociodemographic Predictors of Mental Health in a Representative Sample of Young Adults from Germany, Israel, Poland, and Slovenia: A Longitudinal Study during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckford, R.D.; Gaisser, A.; Arndt, V.; Baumann, M.; Kludt, E.; Mehlis, K.; Ubels, J.; Winkler, E.C.; Weg-Remers, S.; Schlander, M. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Cancer Patients in Germany: Impact on Treatment, Follow-Up Care and Psychological Burden. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 788598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arndt, V.; Doege, D.; Fröhling, S.; Albers, P.; Algül, H.; Bargou, R.; Bokemeyer, C.; Bornhäuser, M.; Brandts, C.H.; Brossart, P.; et al. Cancer care in German centers of excellence during the first 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchberg, J.; Rentsch, A.; Klimova, A.; Vovk, V.; Hempel, S.; Folprecht, G.; Krause, M.; Plodeck, V.; Welsch, T.; Weitz, J.; et al. Influence of the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Cancer Care in a German Comprehensive Cancer Center. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 750479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mink van der Molen, D.R.; Bargon, C.A.; Batenburg, M.C.T.; Gal, R.; Young-Afat, D.A.; van Stam, L.E.; van Dam, I.E.; van der Leij, F.; Baas, I.O.; Ernst, M.F.; et al. (Ex-)breast cancer patients with (pre-existing) symptoms of anxiety and/or depression experience higher barriers to contact health care providers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 186, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, O.A.; Poyraz, K.; Erdur, E. Depression and anxiety in cancer patients before and during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: Association with treatment delays. Qual. Life Res. Int. J. Qual. Life Asp. Treat. Care Rehabil. 2021, 30, 1903–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruessmann, J.; Pursche, T.; Hammersen, F.; Katalinic, A.; Fischer, D.; Waldmann, A. Conditional Disease-Free and Overall Survival of 1858 Young Women with Non-Metastatic Breast Cancer and with Participation in a Post-Therapeutic Rehab Programme according to Clinical Subtypes. Breast Care 2021, 16, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pursche, T.; Bauer, J.; Hammersen, F.; Rody, A.; Waldmann, A.; Fischer, D. Early-Onset Breast Cancer: Effect of Diagnosis and Therapy on Fertility Concerns, Endocrine System, and Sexuality of Young Mothers in Germany. Breast Care 2019, 14, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pursche, T.; Hedderich, M.; Heinrichs, A.; Baumann, K.; Banz-Jansen, C.; Rody, A.; Waldmann, A.; Fischer, D. Guideline conformity treatment in young women with early-onset breast cancer in Germany. Breast Care 2014, 9, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salas, M.; Mordin, M.; Castro, C.; Islam, Z.; Tu, N.; Hackshaw, M.D. Health-related quality of life in women with breast cancer: A review of measures. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayers, P.M.; Aaronson, N.; Bjordal, K.; Groenvold, M.; Curran, D.; Bottomley, A. EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual; EORTC Data Center: Brussels, Belgium, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brouckaert, O.; Laenen, A.; Vanderhaegen, J.; Wildiers, H.; Leunen, K.; Amant, F.; Berteloot, P.; Smeets, A.; Paridaens, R.; Christiaens, M.R.; et al. Applying the 2011 St Gallen panel of prognostic markers on a large single hospital cohort of consecutively treated primary operable breast cancers. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 2578–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altman, D.; Machin, D.; Bryant, T.; Gardner, M. Statistics with Confidence: Confidence Intervals and Statistical Guidelines; BMJ Books: London, UK, 2000; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Eisinga, R.; Grotenhuis, M.; Pelzer, B. The reliability of a two-item scale: Pearson, Cronbach, or Spearman-Brown? Int. J. Public Health 2013, 58, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, E.; Mendoza Schulz, L.; Reuss-Borst, M. Quality of life after cancer-How the extent of impairment is influenced by patient characteristics. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjermstad, M.J.; Fayers, P.M.; Bjordal, K.; Kaasa, S. Using reference data on quality of life--the importance of adjusting for age and gender, exemplified by the EORTC QLQ-C30 (+3). Eur. J. Cancer 1998, 34, 1381–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sozialgesetzbuch, S.G.B. Sechstes Buch (VI)-Gesetzliche Rentenversicherung-(Artikel 1 des Gesetzes v. 18. Dezember 1989 BIS, 1990 I S. 1137), Zuletzt Geändert Durch Artikel 4 des Gesetzes vom 7. November 2022 (BGBl. I S. 1985). § 31 SGB VI: Sonstige Leistungen; Bundesministerium der Justiz: Berlin, Germany, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Reha-Recht.de. Angebote der Onkologischen Rehabilitation in Deutschland Noch zu Selten Genutzt. Available online: https://www.reha-recht.de/infothek/beitrag/artikel/angebote-der-onkologischen-rehabilitation-in-deutschland-noch-zu-selten-genutzt/ (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Deck, R.; Babaev, V.; Katalinic, A. Gründe für die Nichtinanspruchnahme einer onkologischen Rehabilitation. Ergebnisse einer schriftlichen Befragung von Patienten aus onkologischen Versorgungszentren. Die Rehabil. 2019, 58, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäuerle, A.; Teufel, M.; Musche, V.; Weismüller, B.; Kohler, H.; Hetkamp, M.; Dörrie, N.; Schweda, A.; Skoda, E.M. Increased generalized anxiety, depression and distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study in Germany. J. Public Health 2020, 42, 672–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercieca-Bebber, R.; Campbell, R.; Fullerton, D.J.; Kleitman, S.; Costa, D.S.J.; Candelaria, D.; Tait, M.A.; Norman, R.; King, M. Health-related quality of life of Australians during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic: A comparison with pre-pandemic data and factors associated with poor outcomes. Qual. Life Res. 2023, 32, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, L.; Jiang, M.; Wang, W.; Zhou, X.; Shao, J. Factors associated with psychological distress among patients with breast cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study in Wuhan, China. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 4773–4782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juanjuan, L.; Santa-Maria, C.A.; Hongfang, F.; Lingcheng, W.; Pengcheng, Z.; Yuanbing, X.; Yuyan, T.; Zhongchun, L.; Bo, D.; Meng, L.; et al. Patient-reported Outcomes of Patients With Breast Cancer During the COVID-19 Outbreak in the Epicenter of China: A Cross-sectional Survey Study. Clin. Breast Cancer 2020, 20, e651–e662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoda, E.-M.; Spura, A.; De Bock, F.; Schweda, A.; Dörrie, N.; Fink, M.; Musche, V.; Weismüller, B.; Benecke, A.; Kohler, H.; et al. Veränderung der psychischen Belastung in der COVID-19-Pandemie in Deutschland: Ängste, individuelles Verhalten und die Relevanz von Information sowie Vertrauen in Behörden. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundh-Gesundh. 2021, 64, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. Coronavirus-Pandemie: Was Geschah Wann? Available online: https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/coronavirus/chronik-coronavirus.html (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Varma, P.; Junge, M.; Meaklim, H.; Jackson, M.L. Younger people are more vulnerable to stress, anxiety and depression during COVID-19 pandemic: A global cross-sectional survey. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 109, 110236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doege, D.; Thong, M.S.; Koch-Gallenkamp, L.; Bertram, H.; Eberle, A.; Holleczek, B.; Pritzkuleit, R.; Waldeyer-Sauerland, M.; Waldmann, A.; Zeissig, S.R.; et al. Health-related quality of life in long-term disease-free breast cancer survivors versus female population controls in Germany. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 175, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldmann, A.; Pritzkuleit, R.; Raspe, H.; Katalinic, A. The OVIS study: Health related quality of life measured by the EORTC QLQ-C30 and -BR23 in German female patients with breast cancer from Schleswig-Holstein. Qual. Life Res. 2007, 16, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, D.K.u.A.). Supportive Therapie bei Onkologischen PatientInnen-Langversion 1.3, AWMF Registernummer: 032/054OL. Available online: https://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/supportive-therapie/ (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- German Guideline Program in Oncology (German Cancer Society and German Cancer Aid and AWMF). Interdisciplinary Evidence-Based Practice Guideline for the Early Detection, Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up of Breast Cancer. Long Version 4.4. AWMF Registration Number: 032/045OL. Available online: https://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/mammakarzinom/ (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Zou, G.; Simons, A.; Toland, S. An exploration of the effects of information giving and information needs of women with newly diagnosed early-stage breast cancer: A mixed-method systematic review. Nurs. Open 2022, 9, 2586–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergelt, C.; Bokemeyer, C.; Hilgendorf, I.; Langer, T.; Rick, O.; Seifart, U.; Koch-Gromus, U. Langzeitüberleben bei Krebs: Definitionen, Konzepte und Gestaltungsprinzipien von Survivorship-Programmen. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz 2022, 65, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistisches Bundesamt (DESTATIS). Einkommen, Einnahmen und Ausgaben Privater Haushalte in Deutschland. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Einkommen-Konsum-Lebensbedingungen/Einkommen-Einnahmen-Ausgaben/Tabellen/deutschland-lwr.html (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Nolte, S.; Liegl, G.; Petersen, M.A.; Aaronson, N.K.; Costantini, A.; Fayers, P.M.; Groenvold, M.; Holzner, B.; Johnson, C.D.; Kemmler, G.; et al. General population normative data for the EORTC QLQ-C30 health-related quality of life questionnaire based on 15,386 persons across 13 European countries, Canada and the Unites States. Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 107, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 2015–2017 (n = 388) | 2018–March 2020 (n = 323) | July 2020–2021 (n = 142) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | (Mean (SD)) | 35.1 (3.1) | 35.1 (3.1) | 35.8 (2.6) |

| Months between diagnosis and rehab | (Mean (SD)) | 11.3 (3.6) | 12.7 (3.6) | 14.7 (4.2) |

| Patient has permanent partner | No | 42 (10.8) | 39 (12.1) | 18 (12.7) |

| Yes | 328 (84.5) | 274 (84.8) | 118 (83.1) | |

| Unknown | 18 (4.6) | 10 (3.1) | 6 (4.2) | |

| Education 1 | Low | 18 (4.6) | 19 (5.9) | 7 (4.9) |

| Intermediate | 208 (53.6) | 168 (52.0) | 66 (46.5) | |

| High | 157 (40.5) | 131 (40.6) | 69 (48.6) | |

| Unknown | 5 (1.3) | 5 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Work situation | Worker | 31 (8.0) | 27 (8.4) | 8 (5.6) |

| Employee/ Civil servant | 331 (85.3) | 272 (84.2) | 128 (90.1) | |

| Self-employed/ Freelancer | 14 (3.6) | 15 (4.6) | 3 (2.1) | |

| Unknown | 12 (3.1) | 9 (2.8) | 3 (2.1) | |

| Income 2 | EUR < 1500 | 53 (13.7) | 48 (14.9) | 10 (7.0) |

| EUR 1500–3000 | 159 (41.0) | 120 (37.2) | 46 (32.4) | |

| EUR > 3000 | 162 (41.8) | 145 (44.9) | 85 (59.9) | |

| Unknown | 14 (3.6) | 10 (3.1) | 1 (0.7) | |

| 2015–2017 (n = 388) | 2018–March 2020 (n = 323) | July 2020–2021 (n = 142) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumour size (TNM-T) | T in situ | 15 (3.9) | 23 (7.1) | 4 (2.8) |

| T0 | 90 (23.2) | 104 (32.2) | 60 (42.3) | |

| T1 | 158 (40.7) | 129 (39.9) | 51 (35.9) | |

| T2 | 107 (27.6) | 56 (17.3) | 22 (15.5) | |

| T3 | 15 (3.9) | 7 (2.2) | 4 (2.8) | |

| T4 | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.7) | |

| TX/unknown | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Nodal status (TNM-N) | N0 | 257 (66.2) | 232 (71.8) | 103 (72.5) |

| N1 | 94 (24.2) | 67 (20.7) | 26 (18.3) | |

| N2 | 25 (6.4) | 13 (4.0) | 9 (6.3) | |

| N3 | 8 (2.1) | 2 (0.6) | 4 (2.8) | |

| NX/unknown | 4 (1.0) | 9 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Grading | G1 | 24 (6.2) | 10 (3.1) | 5 (3.5) |

| G2 | 140 (36.1) | 119 (36.8) | 48 (33.8) | |

| G3 | 197 (50.8) | 173 (53.6) | 81 (57.0) | |

| GX/unknown | 27 (7.0) | 21 (6.5) | 8 (5.6) | |

| Tumour biology 1 | Luminal A | 50 (12.9) | 30 (9.3) | 17 (12.0) |

| Luminal B/B1 | 96 (24.7) | 99 (30.7) | 43 (30.3) | |

| Luminal Her2+/B2 | 90 (23.2) | 69 (21.4) | 27 (19.0) | |

| Her2-like/non-luminal Her2+ | 30 (7.7) | 28 (8.7) | 6 (4.2) | |

| triple-negative/basal-like | 99 (25.5) | 84 (26.0) | 41 (28.9) | |

| Unknown | 23 (5.9) | 13 (4.0) | 8 (5.6) | |

| Positive family anamnesis for BC | No | 201 (51.8) | 146 (45.2) | 54 (38.0) |

| Yes | 152 (39.2) | 109 (33.7) | 54 (38.0) | |

| Unknown | 35 (9.0) | 68 (21.1) | 34 (23.9) |

| 2015–2017 (n = 388) | 2018–March 2020 (n = 323) | July 2020–2021 (n = 142) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode of surgery | Breast-conserving treatment | 214 (55.2) | 174 (53.9) | 74 (52.1) |

| Mastectomy without reconstruction | 45 (11.6) | 38 (11.8) | 17 (12.0) | |

| Mastectomy with reconstruction | 126 (32.5) | 105 (32.5) | 45 (31.7) | |

| Other | 1 (0.3) | 4 (1.2) | 2 (1.4) | |

| Had surgery, but no further information | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.6) | 4 (2.8) | |

| Radiotherapy (RT) | No RT | 85 (21.9) | 87 (26.9) | 30 (21.1) |

| RT | 299 (77.1) | 233 (72.1) | 107 (75.4) | |

| Unknown | 4 (1.0) | 3 (0.9) | 5 (3.5) | |

| Chemotherapy (CT) | No CT | 36 (9.3) | 32 (9.9) | 12 (8.5) |

| CT with HER-2 targeted therapy | 94 (24.2) | 88 (27.2) | 32 (22.5) | |

| CT without HER-2 targeted therapy | 246 (63.4) | 200 (61.9) | 96 (67.6) | |

| CT, medication acc. to study protocol/unknown substances | 12 (3.1) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Hormone therapy (HT) | No HT | 137 (35.3) | 126 (39.0) | 50 (35.2) |

| HT with SERM 1 | 234 (60.3) | 176 (54.5) | 71 (50.0) | |

| HT with AI 2 | 11 (2.8) | 14 (4.3) | 13 (9.2) | |

| HT with GnRH 3 | 3 (0.8) | 7 (2.2) | 5 (3.5) | |

| HT with unknown substances | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.1) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 Scale | Values Indicating the Need for Supportive Care 1 | Baseline (n = 176) | Follow-Up (n = 176) | Statistical Significance 2 | Effect Size 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Health Status/QOL | values < 71 | 105 (59.7) | 95 (54) | Chi2(df 1) = 1.45; p = 0.229 | −0.08 (−0.2; 0.04) |

| Physical Functioning | values < 97 | 135 (76.7) | 115 (65.3) | Chi2(df 1) = 7.2; p = 0.007 | −0.21 (−0.34; −0.08) |

| Role Functioning | values < 92 | 130 (73.9) | 100 (56.8) | Chi2(df 1) = 11.05; p = 0.001 | −0.21 (−0.31; −0.11) |

| Emotional Functioning | values < 71 | 151 (85.8) | 139 (79) | Chi2(df 1) = 3.69; p = 0.055 | −0.17 (−0.32; −0.01) |

| Social Functioning | values < 92 | 149 (84.7) | 131 (74.4) | Chi2(df 1) = 6.02; p = 0.014 | −0.19 (−0.32; −0.05) |

| Fatigue | values > 28 | 133 (75.6) | 119 (67.6) | Chi2(df 1) = 3.36; p = 0.067 | −0.17 (−0.32; −0.02) |

| Nausea and Vomiting | values > 8 | 37 (21) | 30 (17) | Chi2(df 1) = 0.66; p = 0.417 | −0.08 (−0.24; 0.09) |

| Pain | values > 8 | 128 (72.7) | 122 (69.3) | Chi2(df 1) = 0.43; p = 0.511 | −0.05 (−0.19; 0.08) |

| Insomnia | values > 17 | 134 (76.1) | 121 (68.8) | Chi2(df 1) = 3.02; p = 0.082 | −0.15 (−0.3; −0.01) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hammersen, F.; Fischer, D.; Pursche, T.; Strobel, A.M.; Katalinic, A.; Labohm, L.; Waldmann, A. Young Adult German Breast Cancer Patients Participating in a Three-Week Inpatient Mother–Child Rehab Program Have High Needs for Supportive Care. Cancers 2023, 15, 1770. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15061770

Hammersen F, Fischer D, Pursche T, Strobel AM, Katalinic A, Labohm L, Waldmann A. Young Adult German Breast Cancer Patients Participating in a Three-Week Inpatient Mother–Child Rehab Program Have High Needs for Supportive Care. Cancers. 2023; 15(6):1770. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15061770

Chicago/Turabian StyleHammersen, Friederike, Dorothea Fischer, Telja Pursche, Angelika M. Strobel, Alexander Katalinic, Louisa Labohm, and Annika Waldmann. 2023. "Young Adult German Breast Cancer Patients Participating in a Three-Week Inpatient Mother–Child Rehab Program Have High Needs for Supportive Care" Cancers 15, no. 6: 1770. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15061770

APA StyleHammersen, F., Fischer, D., Pursche, T., Strobel, A. M., Katalinic, A., Labohm, L., & Waldmann, A. (2023). Young Adult German Breast Cancer Patients Participating in a Three-Week Inpatient Mother–Child Rehab Program Have High Needs for Supportive Care. Cancers, 15(6), 1770. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15061770