Ultrastaging of the Parametrium in Cervical Cancer: A Clinicopathological Study

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

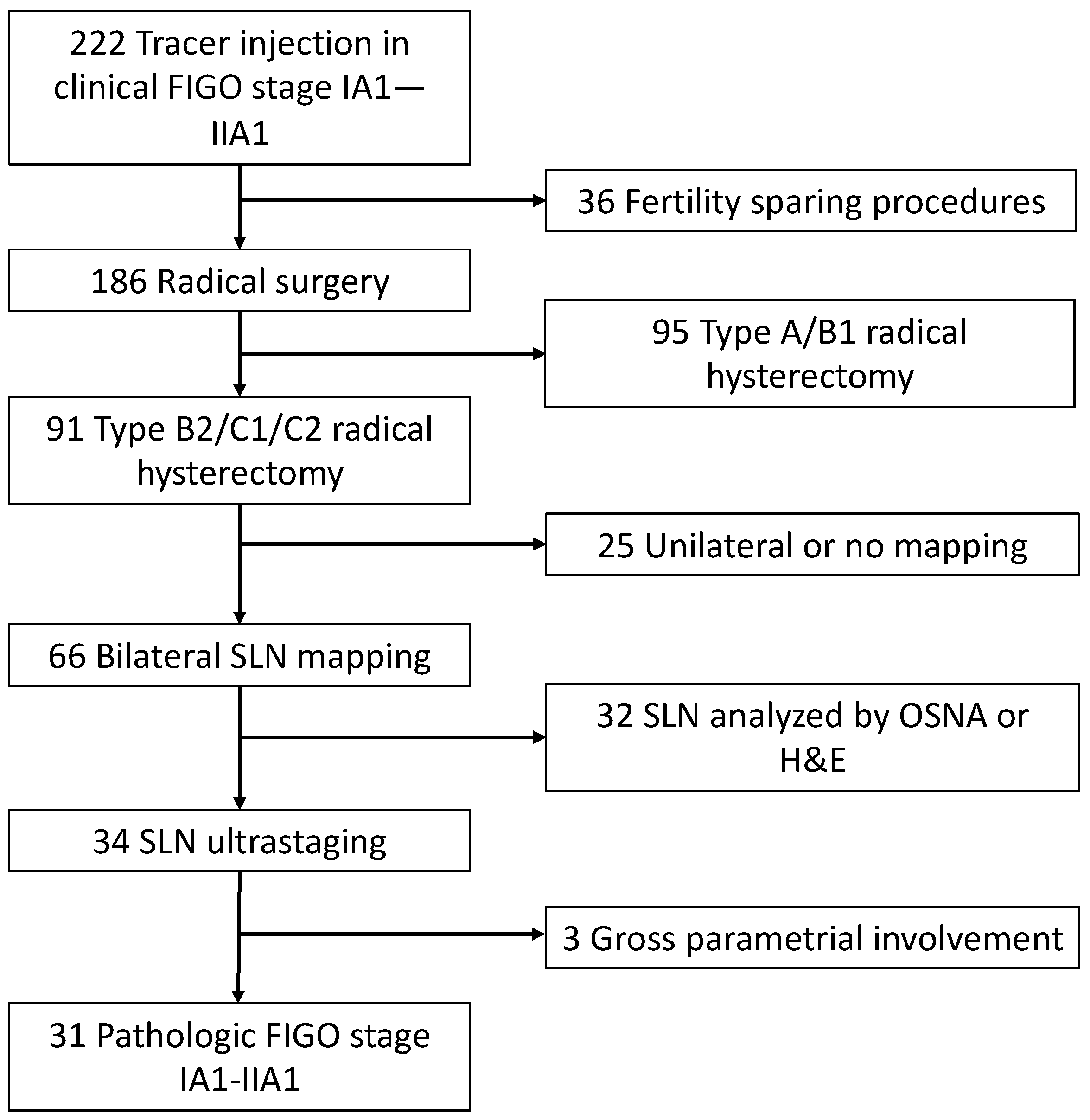

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients Characteristics

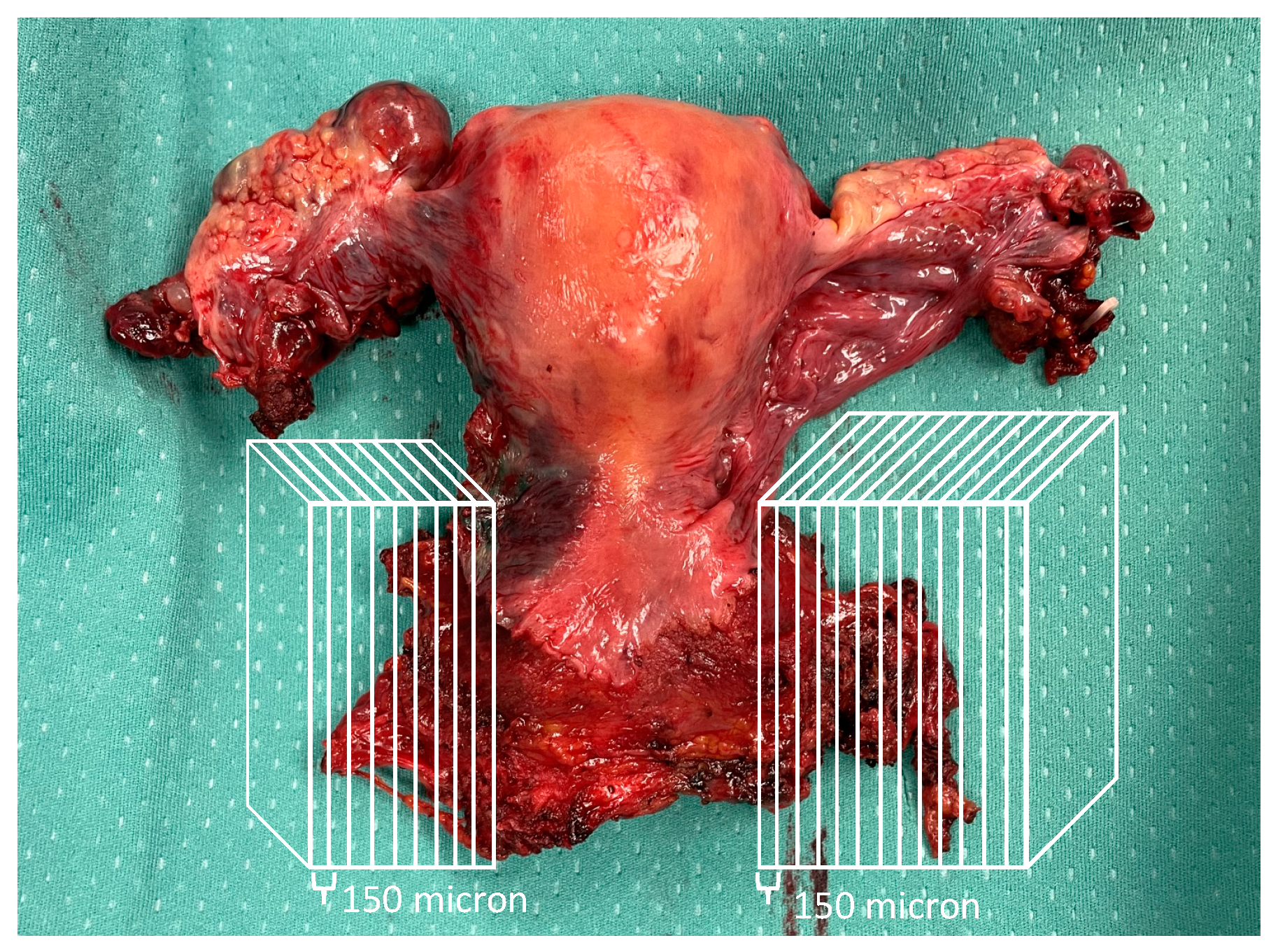

2.2. Ultrastaging of Parametrial Tissue

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peters, W.A., 3rd; Liu, P.Y.; Barrett, R.J., 2nd; Stock, R.J.; Monk, B.J.; Berek, J.S.; Souhami, L.; Grigsby, P.; Gordon, W., Jr.; Alberts, D.S. Concurrent Chemotherapy and Pelvic Radiation Therapy Compared with Pelvic Radiation Therapy Alone as Adjuvant Therapy After Radical Surgery in High-Risk Early-Stage Cancer of the Cervix. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000, 18, 1606–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumovitz, M.; Sun, C.C.; Schmeler, K.M.; Deavers, M.T.; dos Reis, R.; Levenback, C.F.; Ramirez, P.T. Parametrial Involvement in Radical Hysterectomy Specimens for Women with Early-Stage Cervical Cancer. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 114, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yang, S.; Hua, K. Nomogram Predicting Parametrial Involvement Based on the Radical Hysterectomy Specimens in the Early-Stage Cervical Cancer. Front. Surg. 2021, 8, 759026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.D.; Grigsby, P.W.; Brooks, R.; Powell, M.A.; Gibb, R.K.; Gao, F.; Rader, J.S.; Mutch, D.G. Utility of parametrectomy for early stage cervical cancer treated with radical hysterectomy. Cancer 2007, 110, 1281–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghardt, E.; Haas, J.; Girardi, F. 13 The significance of the parametrium in the operative treatment of cervical cancer. Baillieres Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1988, 2, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landoni, F.; Bocciolone, L.; Perego, P.; Maneo, A.; Bratina, G.; Mangioni, C. Cancer of the cervix, FIGO stages IB and IIA: Patterns of local growth and paracervical extension. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 1995, 5, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaya, V.; Bresset, A.; Guani, B.; Benoit, L.; Magaud, L.; Bonsang-Kitzis, H.; Ngo, C.; Mathevet, P.; Lécuru, F.; SENTICOL group. Pre-operative surgical algorithm: Sentinel lymph node biopsy as predictor of parametrial involvement in early-stage cervical cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2020, 30, 1317–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lührs, O.; Ekdahl, L.; Geppert, B.; Lönnerfors, C.; Persson, J. Resection of the upper paracervical lymphovascular tissue should be an integral part of a pelvic sentinel lymph node algorithm in early stage cervical cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 163, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, A.; Angelico, G.; Inzani, F.; Arciuolo, D.; Spadola, S.; Valente, M.; D’Alessandris, N.; Piermattei, A.; Fiorentino, V.; Cianfrini, F.; et al. Standard ultrastaging compared to one-step nucleic acid amplification (OSNA) for the detection of sentinel lymph node metastases in early stage cervical cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2020, 30, 1871–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querleu, D.; Cibula, D.; Abu-Rustum, N.R. 2017 Update on the Querleu–Morrow Classification of Radical Hysterectomy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 24, 3406–3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, P.T.; Frumovitz, M.; Pareja, R.; Lopez, A.; Vieira, M.; Ribeiro, M.; Buda, A.; Yan, X.; Shuzhong, Y.; Chetty, N.; et al. Minimally Invasive versus Abdominal Radical Hysterectomy for Cervical Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 1895–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cibula, D.; Pötter, R.; Planchamp, F.; Avall-Lundqvist, E.; Fischerova, D.; Meder, C.H.; Köhler, C.; Landoni, F.; Lax, S.; Lindegaard, J.C.; et al. The European Society of Gynaecological Oncology/European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology/European Society of Pathology Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Cervical Cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2018, 28, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzarri, N.; Luigi, P.A.; Ferrandina, G.; Zannoni, G.F.; Carbone, M.V.; Fedele, C.; Teodorico, E.; Gallotta, V.; Alletti, S.G.; Chiantera, V.; et al. Sentinel lymph node mapping with indocyanine green in cervical cancer patients undergoing open radical hysterectomy: A single-institution series. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 147, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olawaiye, A.B.; Mutch, D.G. Lymphnode staging update in the American Joint Committee on Cancer 8th Edition cancer staging manual. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 150, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querleu, D.; Fanfani, F.; Fagotti, A.; Bizzarri, N.; Scambia, G. What is paracervical lymphadenectomy? Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2021, 38, 100891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Querleu, D.; Bizzarri, N.; Fanfani, F.; Fagotti, A.; Scambia, G. Simplified anatomical nomenclature of lateral female pelvic spaces. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibula, D.; Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Dušek, L.; Zikan, M.; Zaal, A.; Sevcik, L.; Kenter, G.G.; Querleu, D.; Jach, R.; Bats, A.-S.; et al. Prognostic significance of low volume sentinel lymph node disease in early-stage cervical cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2012, 124, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardi, F.; Lichtenegger, W.; Tamussino, K.; Haas, J. The importance of parametrial lymph nodes in the treatment of cervical cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 1989, 34, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti-Panici, P.; Maneschi, F.; Scambia, G.; Greggi, S.; Cutillo, G.; D’Andrea, G.; Rabitti, C.; Coronetta, F.; Capelli, A.; Mancuso, S. Lymphatic Spread of Cervical Cancer: An Anatomical and Pathological Study Based on 225 Radical Hysterectomies with Systematic Pelvic and Aortic Lymphadenectomy. Gynecol. Oncol. 1996, 62, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, R.; Haas, J.; Reich, O.; Koemetter, R.; Tamussino, K.; Lahousen, M.; Petru, E.; Pickel, H. Parametrial Spread of Cervical Cancer in Patients with Negative Pelvic Lymph Nodes. Gynecol. Oncol. 2002, 84, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrandina, G.; Anchora, L.P.; Gallotta, V.; Fagotti, A.; Vizza, E.; Chiantera, V.; DE Iaco, P.; Ercoli, A.; Corrado, G.; Bottoni, C.; et al. Can We Define the Risk of Lymph Node Metastasis in Early-Stage Cervical Cancer Patients? A Large-Scale, Retrospective Study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 24, 2311–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvo, G.; Odetto, D.; Pareja, R.; Frumovitz, M.; Ramirez, P.T. Revised 2018 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) cervical cancer staging: A review of gaps and questions that remain. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2020, 30, 873–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatla, N.; Aoki, D.; Sharma, D.N.; Sankaranarayanan, R. Cancer of the cervix uteri: 2021 update. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 155 (Suppl. S1), 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | N = 31 N (%), Median (Range) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 44 (27–68) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24 (17–35) |

| FIGO 2018 stage | |

| IA1 | 6 (19.4) |

| IA2 | 3 (9.7) |

| IB1 | 8 (25.8) |

| IB2 | 7 (22.6) |

| IB3 | 2 (6.5) |

| IIA1 | 1 (3.2) |

| IIIC1p | 4 (12.9) |

| Histology | |

| SCC | 20 (64.5) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 11 (35.5) |

| Surgical approach | |

| Laparotomy | 14 (45.2) |

| Laparoscopy | 12 (38.7) |

| Robot | 5 (16.1) |

| Radicality of hysterectomy (Querleu–Morrow) | |

| B2 | 11 (35.5) |

| C1 | 20 (64.5) |

| Lymph node assessment | |

| SLN only | 5 (16.1) |

| SLN + pelvic lymphadenectomy | 26 (83.9) |

| Histological tumor diameter (mm) | 17 (1–60) |

| LVSI | |

| Negative | 18 (58.1) |

| Positive | 11 (35.5) |

| Unknown | 2 (6.5) |

| Grading | |

| Well-differentiated | 1 (3.2) |

| Moderately differentiated | 17 (54.8) |

| Poorly differentiated | 7 (22.6) |

| Unknown | 6 (19.4) |

| Depth of stromal infiltration | |

| <50% | 19 (61.3) |

| ≥50% | 12 (38.7) |

| Pathologic tumor diameter | |

| <2 cm | 17 (54.8) |

| ≥2 cm | 14 (45.2) |

| Metastatic pelvic lymph nodes | |

| SLN only | 4 (12.9) |

| SLN and non-SLN | 1 (3.2) |

| Non-SLN only | 1 (3.2) |

| Volume of lymph node metastasis * | |

| ITC | 2 (6.4) |

| Micrometastasis | 1 (3.2) |

| Macrometastasis | 3 (9.7) |

| Adjuvant treatment | |

| No | 18 (58.1) |

| Radiotherapy | 8 (25.8) |

| Chemoradiotherapy | 5 (16.1) |

| Characteristic | Negative Lymph Nodes (N = 25) N (%), Median (Range) | Metastatic Lymph Nodes (N = 6) N (%), Median (Range) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 44 (27–68) | 47 (34–55) | 0.822 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24 (17–35) | 25 (20.5–27) | 0.781 |

| Histology SCC Adenocarcinoma | 15 (60.0) 10 (40.0) | 5 (83.3) 1 (16.7) | 0.383 |

| Surgical approach Laparotomy Minimally invasive | 12 (48.0) 13 (52.0) | 2 (33.3) 4 (66.7) | 0.664 |

| LVSI Negative Positive Unknown | 16 (64.0) 7 (28.0) 2 (8.0) | 2 (33.3) 4 (66.7) 0 | 0.103 |

| Grading Well-differentiated Moderately differentiated Poorly differentiated Unknown | 1 (4.0) 16 (64.0) 5 (20.0) 3 (12.0) | 0 1 (16.7) 2 (33.3) 3 (50.0) | 0.278 |

| Depth of stromal infiltration <50% ≥50% | 16 (64.0) 9 (36.0) | 3 (50.0) 3 (50.0) | 0.653 |

| Pathologic tumor diameter <2 cm ≥2 cm | 14 (56.0) 11 (44.0) | 3 (50.0) 3 (50.0) | 0.791 |

| Parametrial lymph nodes Negative Positive | 25 (100) 0 | 5 (83.3) 1 (16.7) | 0.038 |

| Tumor Characteristics | SLN | Non-SLN | Parametrial Involvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage: IB1, Diam:20, LVSI: pos, Hist: SCC, DOI: ≥50%, G3 | R: macro L: macro | R: negative L: negative | Negative |

| Stage: IB1, Diam:21, LVSI: pos, Hist: SCC, DOI: ≥50%, G3 | R: macro L: negative | R: macro L: negative | Positive (lymph node) |

| Stage: IA2, Diam:5, LVSI: neg, Hist: SCC, DOI: <50%, Gx | R: ITC L: negative | R: negative L: negative | Negative |

| Stage: IB1, Diam:7, LVSI: pos, Hist: SCC, DOI: <50%, G1 | R: negative L: micro | R: negative L: negative | Negative |

| Stage: IA1, Diam:2, LVSI: neg, Hist: ADC, DOI: <50%, Gx | R: negative L: ITC | R: negative L: negative | Negative |

| Stage: IIA1, Diam:21, LVSI: pos, Hist: SCC, DOI: ≥50%, G2 | R: negative L: negative | R: macro L: negative | Negative |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bizzarri, N.; Arciuolo, D.; Certelli, C.; Pedone Anchora, L.; Gallotta, V.; Teodorico, E.; Carbone, M.V.; Piermattei, A.; Fanfani, F.; Fagotti, A.; et al. Ultrastaging of the Parametrium in Cervical Cancer: A Clinicopathological Study. Cancers 2023, 15, 1099. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15041099

Bizzarri N, Arciuolo D, Certelli C, Pedone Anchora L, Gallotta V, Teodorico E, Carbone MV, Piermattei A, Fanfani F, Fagotti A, et al. Ultrastaging of the Parametrium in Cervical Cancer: A Clinicopathological Study. Cancers. 2023; 15(4):1099. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15041099

Chicago/Turabian StyleBizzarri, Nicolò, Damiano Arciuolo, Camilla Certelli, Luigi Pedone Anchora, Valerio Gallotta, Elena Teodorico, Maria Vittoria Carbone, Alessia Piermattei, Francesco Fanfani, Anna Fagotti, and et al. 2023. "Ultrastaging of the Parametrium in Cervical Cancer: A Clinicopathological Study" Cancers 15, no. 4: 1099. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15041099

APA StyleBizzarri, N., Arciuolo, D., Certelli, C., Pedone Anchora, L., Gallotta, V., Teodorico, E., Carbone, M. V., Piermattei, A., Fanfani, F., Fagotti, A., Ferrandina, G., Zannoni, G. F., Scambia, G., & Querleu, D. (2023). Ultrastaging of the Parametrium in Cervical Cancer: A Clinicopathological Study. Cancers, 15(4), 1099. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15041099