Changes in Sexuality and Sexual Dysfunction over Time in the First Two Years after Treatment of Head and Neck Cancer

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

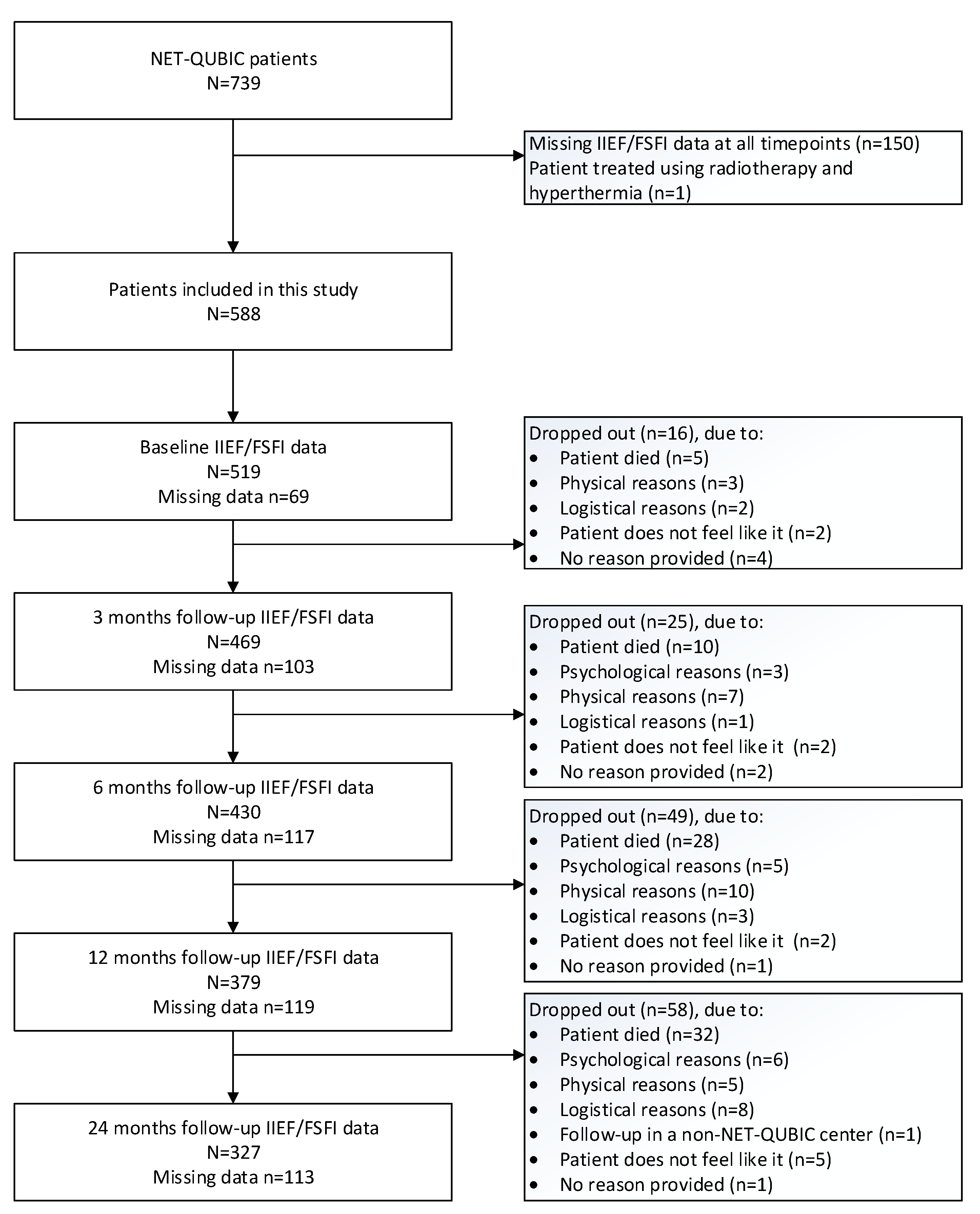

2.1. Patients and Procedures

2.2. Sample Size Calculation

2.3. Outcome Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Changes over Time in Sexuality

3.3. Changes over Time in Sexual Dysfunction among Sexually Active HNC Patients

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cancer Today. 2020. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/home (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Rhoten, B.A. Head and neck cancer and sexuality: A review of the literature. Cancer Nurs. 2016, 39, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regeer, J.; Enzlin, P.; Prekatsounaki, S.; Van Der Cruyssen, F.; Politis, C.; Dormaar, J.T. Sexuality and intimacy after head and neck cancer treatment: An explorative prospective pilot study. Dent. Med. Probl. 2022, 59, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, L.M.A.; Donovan, K.A. Discussions about sexual health: An unmet need among patients with human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2021, 110, 394–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casswell, G.; Gough, K.; Drosdowsky, A.; Bressel, M.; Coleman, A.; Shrestha, S.; D’costa, I.; Fua, T.; Tiong, A.; Liu, C.; et al. Sexual health interpersonal relationships after chemoradiation therapy for human papillomavirus-associated oropharyngeal cancer: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2021, 110, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, M.; Adnan, A.; Högmo, A.; Sjödin, H.; Gebre-Medhin, M.; Laurell, G.; Reizenstein, J.; Farnebo, L.; Norberg, L.S.; Notstam, I.; et al. A national study of health-related quality of life in patients with cancer of the base of the tongue compared to the general population and to patients with tonsillar carcinoma. Head Neck 2021, 43, 3843–3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melissant, H.; Jansen, F.; Schutte, L.; Lissenberg-Witte, B.; Buter, J.; Leemans, C.; Sprangers, M.; Vergeer, M.; Laan, E.; Verdonck-de Leeuw, I.V. The course of sexual interest and enjoyment in head and neck cancer patients treated with primary (chemo)radiotherapy. Oral Oncol. 2018, 83, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDowell, L.; So, N.; Keshavarzi, S.; Xu, W.; Rock, K.; Chan, B.; Waldron, J.; Bernstein, L.J.; Huang, S.H.; Giuliani, M.; et al. Sexual satisfaction in nasopharyngeal carcinoma survivors: Rates and determinants. Oral Oncol. 2020, 109, 104865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humbert, M.; Lequesne, J.; Licaj, I.; Bon-Mardion, N.; Bouhnik, A.D.; Huyghe, E.; Dugue, J.; Babin, E.; Rhamati, L. Sexual health at 5 years after diagnosis of head and neck cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdonck-de Leeuw, I.M.; Jansen, F.; Brakenhoff, R.H.; Langendijk, J.A.; Takes, R.; Terhaard, C.H.J.; Baatenburg de Jong, R.J.; Smit, J.H.; Leemans, C.R. Advancing interdisciplinary research in head and neck cancer through a multicenter longitudinal prospective cohort study: The NETherlands QUality of life and BIomedical Cohort (NET-QUBIC) data warehouse and biobank. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 765. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, R.C.; Riley, A.; Wagner, G.; Osterloh, I.H.; Kirkpatrick, J.; Mishra, A. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): A multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology 1997, 49, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, C.; Brown, J.; Heiman, S.; Leiblum, C.; Meston, R.; Shabsigh, D.; Ferguson, R.; D’Agostino, R. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J. Sex Marital. Ther. 2000, 26, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiegel, M.; Meston, C.; Rosen, R. The female sexual function index (FSFI): Cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. J. Sex Marital. Ther. 2005, 31, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiltink, J.; Hauck, E.W.; Phädayanon, M.; Weidner, W.; Beutel, M.E. Validation of the German version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) in patients with erectile dysfunction, Peyronie’s disease and controls. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2003, 15, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdonck-de Leeuw, I.M.; Melissant, H.; Lissenberg-Witte, B.I.; de Jong, R.J.B.; Heijer, M.D.; Langendijk, J.A.; Leemans, C.R.; Smit, J.H.; Takes, R.P.; Terhaard, C.H.; et al. Associations between testosterone and patient reported sexual outcomes among male and female head and neck cancer patients before and six months after treatment: A pilot study. Oral Oncol. 2021, 121, 105505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera-Woll, L.M.; MPapalia, M.; SR Davis, S.R.; HG Burger, H.G. Androgen insufficiency in women: Diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Hum. Reprod. Update 2004, 10, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salonia, A.; Bettocchi, C.; Carvalho, J.; Corona, G.; Jones, T.H.; Kadioglu, A.; Martinez-Salamanca, I.; Minhas, S.; Serefoǧlu, E.C.; Verze, P. Guideline on Sexual and Reproductive Health. Available online: https://uroweb.org/guideline/sexual-and-reproductive-health/#13 (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- Neijenhuijs, K.I.; Peeters, C.F.W.; van Weert, H.; Cuijpers, P.; Verdonck-de Leeuw, I.M. Symptom clusters among cancer survivors: What can machine learning techniques tell us? BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2021, 21, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, S.N.; Hazeldine, P.; O’Brien, K.; Lowe, D.; Roe, B. How often do head and neck cancer patients raise concerns related to intimacy and sexuality in routine follow-up clinics? Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2015, 272, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N.A.; Ringash, J. Head and Neck Cancer Survivorship Care: A Review of the Current Guidelines and Remaining Unmet Needs. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2018, 19, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdonck-de Leeuw, I.; Dawson, C.; Licitra, L.; Eriksen, J.G.; Hosal, S.; Singer, S.; Laverty, D.P.; Golusinski, W.; Machczynski, P.; Varges Gomes, A.; et al. European Head and Neck Society recommendations for head and neck cancer survivorship care. Oral Oncol. 2022, 133, 106047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Included HNC Patients N = 588 | Included HNC Patients Who Were Sexually Active N = 323 | Excluded HNC Patients (No Data on Sexuality) N = 151 | Difference between Included (N = 588) and Excluded Patients p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age in years (SD) | 63.3 ± 9.5 | 61.9 ± 9.8 | 63.2 ± 10.5 | 0.97 |

| Gender | 0.65 | |||

| 439 (74.7%) | 249 (77.1%) | 110 (72.8%) | |

| 149 (25.3%) | 74 (22.9%) | 41 (27.2%) | |

| Living situation * | <0.001 | |||

| 121 (22.1%) | 41 (13.4%) | 42 (41.2%) | |

| 397 (72.6%) | 249 (81.4%) | 54 (52.9%) | |

| 29 (5.3%) | 16 (5.2%) | 6 (5.9%) | |

| Tumor location | 0.16 | |||

| 165 (28.1%) | 94 (29.1%) | 34 (22.5%) | |

| 208 (35.4%) | 113 (35.0%) | 54 (35.8%) | |

| 36 (6.1%) | 12 (3.7%) | 16 (10.6%) | |

| 160 (27.2%) | 92 (28.5%) | 45 (29.8%) | |

| 19 (3.2%) | 12 (3.7%) | 2 (1.3%) | |

| HPV status (oropharynx only) * | 0.004 | |||

| 112 (61.5%) | 69 (71.1%) | 18 (38.3%) | |

| 70 (38.5%) | 28 (28.9%) | 29 (61.7%) | |

| TNM stage | 0.018 | |||

| 141 (24.0%) | 86 (26.6%) | 22 (14.6%) | |

| 110 (18.7%) | 58 (18.0%) | 22 (14.6%) | |

| 99 (16.8%) | 52 (16.1%) | 28 (18.5%) | |

| 238 (40.5%) | 127 (39.3%) | 79 (52.3%) | |

| Treatment | 0.24 | |||

| 129 (21.9%) | 77 (23.9%) | 23 (15.4%) | |

| 191 (32.5%) | 99 (30.7%) | 50 (33.6%) | |

| 86 (14.6%) | 47 (14.6%) | 20 (13.4%) | |

| 182 (31.0%) | 99 (30.7%) | 56 (37.6%) | |

| WHO performance | 0.002 | |||

| 414 (70.4%) | 236 (73.1%) | 93 (61.6%) | |

| 150 (25.5%) | 79 (24.5%) | 41 (27.2%) | |

| 24 (4.1%) | 8 (2.5%) | 17 (11.3%) | |

| Comorbidity * | 0.007 | |||

| 178 (31.7%) | 115 (37.5%) | 26 (19.0%) | |

| 212 (37.7%) | 116 (37.8%) | 52 (38.0%) | |

| 113 (20.1%) | 53 (17.3%) | 42 (30.7%) | |

| 59 (10.5%) | 23 (7.5%) | 17 (12.4%) |

| All Patients | Sexually Active Patients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3 Months | 6 Months | 12 Months | 24 Months | |||

| IIEF | N, mean (SD) | N, mean (SD) | N, mean (SD) | N, mean (SD) | N, mean (SD) | p-value 1 | p-value 2 |

| Desire | 391 5.3 (2.3) | 356 5.3 (2.3) | 334 5.5 (2.3) | 293 5.5 (2.4) | 251 5.6 (2.2) | 0.34 | 0.23 |

| Erectile function | 367 13.7 (11.2) | 335 13.4 (10.9) | 312 14.1 (11.3) | 278 14.3 (11.2) | 237 14.5 (11.1) | 0.92 | 0.64 |

| Orgasm | 391 4.8 (4.5) | 354 4.8 (4.5) | 330 5.0 (4.6) | 294 5.1 (4.5) | 244 5.3 (4.5) | 0.93 | 0.77 |

| Intercourse satisfaction | 389 4.2 (5.3) | 355 4.1 (5.3) | 333 4.6 (5.4) | 293 4.6 (5.5) | 247 4.7 (5.4) | 0.67 | 0.78 |

| Overall satisfaction | 357 6.4 (2.6) | 326 6.1 (2.6) | 305 6.5 (2.6) | 269 6.5 (2.6) | 225 6.6 (2.5) | 0.01 | 0.033 |

| FSFI | |||||||

| Desire | 128 2.2 (1.2) | 113 2.3 (1.2) | 96 2.2 (1.2) | 85 2.3 (1.3) | 76 2.2 (1.2) | 0.88 | 0.99 |

| Arousal | 124 1.9 (2.2) | 110 1.8 (2.1) | 95 1.8 (2.2) | 81 2.0 (2.2) | 72 2.1 (2.3) | 0.75 | 0.65 |

| Lubrication | 128 1.9 (2.5) | 110 2.0 (2.4) | 95 1.8 (2.5) | 82 2.2 (2.6) | 71 2.0 (2.5) | 0.83 | 0.90 |

| Orgasm | 124 1.9 (2.4) | 109 1.9 (2.4) | 95 1.8 (2.4) | 82 2.1 (2.5) | 70 1.9 (2.5) | 0.74 | 0.74 |

| Satisfaction | 111 3.1 (2.0) | 89 3.0 (1.9) | 84 2.8 (2.0) | 69 3.1 (1.9) | 64 2.8 (1.8) | 0.34 | 0.13 |

| Pain | 117 2.0 (2.6) | 106 2.0 (2.6) | 88 2.0 (2.7) | 76 1.9 (2.6) | 66 1.7 (2.5) | 0.61 | 0.38 |

| All Men | Sexually Active Men | ||||||||

| Baseline | 3 Months | 6 Months | 12 Months | 24 Months | |||||

| IIEF | N, mean (SD) | N, mean (SD) | N, mean (SD) | N, mean (SD) | N, mean (SD) | p-value 2 | p-value 3 | p-value 4 | p-value 5 |

| Desire | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.063 | 0.062 | |||||

| Surgery | N = 77, 5.3 (2.2) | N = 79. 5.5 (2.2) | N = 75, 5.5 (2.1) | N = 68, 5.6 (2.3) | N = 59, 5.5 (2.0) | ||||

| Radiotherapy | N = 136, 4.9 (2.3) | N = 116, 5.3 (2.4) | N = 115, 5.3 (2.4) | N = 92, 5.4 (2.4) | N = 83, 5.3 (2.3) | ||||

| Surgery and radiotherapy | N = 53, 5.1 (2.3) | N = 52, 5.1 (2.1) | N = 42, 5.6 (2.2) | N = 41, 5.5 (2.4) | N = 34, 5.6 (2.4) | ||||

| Chemoradiation 1 | N = 125, 5.7 (2.4) | N = 109, 5.3 (2.5) | N = 102, 5.8 (2.4) | N = 92, 5.6 (2.5) | N = 75, 5.9 (2.3) | ||||

| Erectile function | 0.041 | 0.038 | 0.043 | 0.034 | |||||

| Surgery | N = 70, 13.6 (10.8) | N = 75, 14.9 (10.9) | N = 68, 15.1 (10.8) | N = 63, 14.5 (11.1) | N = 57, 13.8 (10.5) | ||||

| Radiotherapy | N = 130, 12.5 (10.9) | N = 110, 12.0 (10.5) | N = 109, 12.1 (11.0) (4.5) | N = 88, 12.5 (11.1) | N = 76, 12.5 (11.0) | ||||

| Surgery and radiotherapy | N = 44, 11.7 (10.8) | N = 48, 12.4 (10.8) | N = 39, 15.1 (10.4) | N = 38, 14.8 (10.8) | N = 33, 14.1 (11.5) | ||||

| Chemoradiation 1 | N = 123, 15.8 (11.7) | N = 102, 14.2 (11.2) | N = 96, 15.4 (12.0) | N = 89, 15.7 (11.4) | N = 71, 17.3 (11.3) | ||||

| Orgasm | 0.0504 | 0.048 | 0.108 | 0.095 | |||||

| Surgery | N = 77, 4.8 (4.4) | N = 79, 5.6 (4.4) | N = 74, 5.2 (4.5) | N = 69, 5.3 (4.5) | N = 59, 5.3 (4.4) | ||||

| Radiotherapy | N = 141, 4.3 (4.5) | N = 118, 4.1 (4.4) | N = 113, 4.5 (4.5) | N = 92, 4.6 (4.5) | N = 78, 4.5 (4.5) | ||||

| Surgery and radiotherapy | N = 50, 3.9 (4.4) | N = 50, 4.3 (4.5) | N = 41, 5.4 (4.5) | N = 40, 5.7 (4.4) | N = 34, 5.4 (4.6) | ||||

| Chemoradiation1 | N = 123, 5.7 (4.6) | N = 107, 5.0 (4.6) | N = 102, 5.3 (4.7) | N = 93, 5.3 (4.6) | M = 73, 6.0 (4.5) | ||||

| Intercourse satisfaction | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.009 | |||||

| Surgery | N = 75, 3.5 (4.9) | N = 81, 4.4 (5.2) | N = 74, 4.8 (5.1) | N = 68, 4.5 (5.2) | N = 58, 4.3 (5.0) | ||||

| Radiotherapy | N = 141, 3.6 (5.1)3.6 (5, ) | N = 117, 4.0 (5.2) | N = 115, 4.1 (5.4) | N = 93, 3.8 (5.6) | N = 82, 4.3 (5.5) | ||||

| Surgery and radiotherapy | N = 49, 3.4 (4.5) | N = 50, 3.7 (4.9) | N = 43, 4.4 (5.3) | N = 39, 4.8 (5.0) | N = 33, 4.4 (5.3) | ||||

| Chemoradiation 1 | N = 124, 5.4 (5.9)5.4 (5.9) | N = 107, 4.3 (5.5) | N = 101, 5.1 (5.8) | N = 93, 5.2 (5.9) | N = 74, 5.6 (5.7) | ||||

| Overall satisfaction | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.012 | |||||

| Surgery | N = 72, 6.1 (2.4) | N = 78, 5.9 (2.7) | N = 69, 6.3 (2.5) | N = 63, 6.1 (2.6) | N = 54, 6.3 (2.3) | ||||

| Radiotherapy | N = 122, 6.2 (2.8) | N = 104, 6.5 (2.5) | N = 103, 6.5 (2.7) | N = 82, 6.5 (2.8) | N = 74, 6.6 (2.8) | ||||

| Surgery and radiotherapy | N = 48, 5.7 (2.5) | N = 46, 5.8 (2.4) | N = 39, 6.6 (2.3) | N = 37, 6.5 (2.7) | N = 30, 6.5 (2.6) | ||||

| Chemoradiation 1 | N = 115, 6.9 (2.4) | N = 98, 5.9 (2.7) | N = 94, 6.5 (2.8) | N = 87, 6.9 (2.6) | N = 67, 6.9 (2.4) | ||||

| All Women | Sexually Active Women | ||||||||

| Baseline | 3 Months | 6 Months | 12 Months | 24 Months | |||||

| FSFI | N, mean (SD) | N, mean (SD) | N, mean (SD) | N, mean (SD) | N, mean (SD) | p-value 2 | p-value 3 | p-value 4 | p-value 5 |

| Desire | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.031 | 0.026 | |||||

| Surgery | N = 30, 2.5 (1.3) | N = 30, 2.8 (1.3) | N = 27, 2.5 (1.4) | N = 21, 2.5 (1.5) | N = 19, 2.4 (1.5) | ||||

| Radiotherapy | N = 35, 1.9 (0.9) | N = 27, 2.1 (1.1) | N = 23, 2.1 (1.2) | N = 22, 2.1 (1.1) | N = 19, 1.9 (0.9) | ||||

| Surgery and radiotherapy | N = 22, 1.9 (1.0) | N = 22, 2.2 (1.0) | N = 17, 2.4 (1.3) | N = 18, 2.3 (1.2) | N = 15, 2.4 (1.2) | ||||

| Chemoradiation 1 | N = 41, 2.3 (1.4) | N = 34, 1.9 (1.1) | N = 29, 1.9 (1.1) | N = 24, 2.2 (1.4) | N = 23, 2.2 (1.2) | ||||

| Arousal | 0.024 | 0.033 | 0.020 | 0.020 | |||||

| Surgery | N = 29, 2.8 (2.4) | N = 29, 2.7 (2.4) | N = 26, 2.4 (2.5) | N = 20, 2.4 (2.6) | N = 19, 2.6 (2.7) | ||||

| Radiotherapy | N = 35, 1.4 (1.8) | N = 27, 1.7 (1.9) | N = 23, 1.7 (2.1) | N = 22, 1.8 (2.1) | N = 18, 1.6 (2.0) | ||||

| Surgery and radiotherapy | N = 22, 1.4 (2.0) | N = 21, 1.9 (2.1) | N = 16, 2.5 (2.3) | N = 16, 2.3 (2.1) | N = 14, 2.5 (2.3) | ||||

| Chemoradiation 1 | N = 38, 1.9 (2.3) | N = 33, 1.2 (1.8) | N = 30, 1.1 (1.8) | N = 23, 1.7 (2.1) | N = 21, 1.7 (2.1) | ||||

| Lubrication | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.07 | |||||

| Surgery | N = 29, 2.7 (2.7) | N = 30, 2.7 (2.6) | N = 27, 2.4 (2.6) | N = 21, 2.6 (2.8) | N = 19, 2.6 (2.9) | ||||

| Radiotherapy | N = 38, 1.4 (2.3) | N = 26, 2.0 (2.4) | N = 23, 1.9 (2.6) | N = 21, 2.1 (2.7) | N = 18, 1.4 (2.1) | ||||

| Surgery and radiotherapy | N = 22, 1.4 (2.2) | N = 21, 2.0 (2.5) | N = 15, 2.5 (2.7) | N = 16, 2.5 (2.5) | N = 13, 2.6 (2.8) | ||||

| Chemoradiation 1 | N = 39, 2.0 (2.6) | N = 33, 1.3 (2.2) | N = 30, 1.0 (2.0) | N = 24, 1.7 (2.3) | N = 21, 1.6 (2.3) | ||||

| Orgasm | 0.053 | 0.08 | 0.041 | 0.040 | |||||

| Surgery | N = 27 3.3 (2.6) | N = 29, 2.7 (2.6) | N = 27, 2.5 (2.6) | N = 22, 2.6 (2.8) | N = 19, 2.5 (2.8) | ||||

| Radiotherapy | N = 37, 1.3 (2.1) | N = 26, 1.6 (2.1) | N = 23, 1.8 (2.4) | N = 21, 1.8 (2.4) | N = 18, 1.6 (2.3) | ||||

| Surgery and radiotherapy | N = 22, 1.3 (2.0) | N = 21, 2.2 (2.6) | N = 15, 2.1 (2.6) | N = 15, 2.7 (2.6) | N = 13, 2.3 (2.6) | ||||

| Chemoradiation 1 | N = 38, 2.0 (2.5) | N = 33, 1.2 (2.1) | N = 30, 0.9 (2.1) | N = 24, 1.6 (2.2) | N = 20, 1.5 (2.4) | ||||

| Satisfaction | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.15 | |||||

| Surgery | N = 27, 3.7 (2.1) | N = 24, 3.7 (2.0) | N = 24, 3.3 (2.1) | N = 16, 3.6 (2.2) | N = 15, 3.1 (2.1) | ||||

| Radiotherapy | N = 29, 2.7 (1.7) | N = 23, 2.9 (2.0) | N = 20, 2.8 (2.0) | N = 18, 2.7 (1.8) | N = 16, 2.5 (1.5) | ||||

| Surgery and radiotherapy | N = 21, 2.9 (2.1) | N = 19, 2.9 (2.0) | N = 14, 3.1 (1.9) | N = 14, 3.5 (1.7) | N = 13, 3.0 (2.0) | ||||

| Chemoradiation 1 | N = 34, 3.2 (2.1) | N = 23, 2.5 (1.7) | N = 26, 2.2 (1.7) | N = 21, 2.7 (1.7) | N = 20, 2.7 (1.7) | ||||

| Pain | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.11 | |||||

| Surgery | N = 25, 3.0 (2.6) | N = 27, 2.9 (2.7) | N = 24, 3.0 (2.9) | N = 19, 2.5 (2.8) | N = 16, 2.6 (2.8) | ||||

| Radiotherapy | N = 34, 1.6 (2.6) | N = 26, 2.3 (2.8) | N = 21, 2.3 (3.0) | N = 20, 1.9 (2.8) | N = 17, 1.3 (2.3) | ||||

| Surgery and radiotherapy | N = 23, 1.7 (2.5) | N = 21, 2.1 (2.7) | N = 14, 2.3 (2.8) | N = 15, 2.9 (2.8) | N = 12, 2.4 (3.0) | ||||

| Chemoradiation 1 | N = 35, 1.9 (2.7) | N = 32, 1.0 (2.2) | N = 29, 0.8 (2.1) | N = 22, 0.8 (1.8) | N = 21, 1.0 (2.0) | ||||

| Unadjusted (p = 0.038) | Adjusted (p = 0.019) * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| 3 months | ||||

| Surgery | 0.33 | 0.16–0.69 | 0.29 | 0.13–0.67 |

| Radiotherapy | 0.37 | 0.19–0.72 | 0.32 | 0.15–0.67 |

| Surgery and radiotherapy | 0.20 | 0.08–0.45 | 0.15 | 0.06–0.38 |

| Chemoradiation 1 | Reference | |||

| 6 months | ||||

| Surgery | 0.58 | 0.27–1.23 | 0.61 | 0.26–1.44 |

| Radiotherapy | 0.61 | 0.30–1.27 | 0.52 | 0.23–1.18 |

| Surgery and radiotherapy | 0.24 | 0.10–0.61 | 0.22 | 0.08–0.63 |

| Chemoradiation 1 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 12 months | ||||

| Surgery | 0.42 | 0.19–0.91 | 0.45 | 0.18–1.12 |

| Radiotherapy | 0.46 | 0.22–0.96 | 0.36 | 0.16–0.82 |

| Surgery and radiotherapy | 0.32 | 0.13–0.77 | 0.26 | 0.10–0.70 |

| Chemoradiation 1 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 24 months | ||||

| Surgery | 0.51 | 0.22–1.21 | 0.72 | 0.27–1.93 |

| Radiotherapy | 0.50 | 0.22–1.16 | 0.49 | 0.20–1.24 |

| Surgery and radiotherapy | 0.29 | 0.12–0.75 | 0.30 | 0.11–0.84 |

| Chemoradiation 1 | Reference | Reference | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stone, M.A.; Lissenberg-Witte, B.I.; de Bree, R.; Hardillo, J.A.; Lamers, F.; Langendijk, J.A.; Leemans, C.R.; Takes, R.P.; Jansen, F.; Verdonck-de Leeuw, I.M. Changes in Sexuality and Sexual Dysfunction over Time in the First Two Years after Treatment of Head and Neck Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 4755. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15194755

Stone MA, Lissenberg-Witte BI, de Bree R, Hardillo JA, Lamers F, Langendijk JA, Leemans CR, Takes RP, Jansen F, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM. Changes in Sexuality and Sexual Dysfunction over Time in the First Two Years after Treatment of Head and Neck Cancer. Cancers. 2023; 15(19):4755. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15194755

Chicago/Turabian StyleStone, Margot A., Birgit I. Lissenberg-Witte, Remco de Bree, Jose A. Hardillo, Femke Lamers, Johannes A. Langendijk, C. René Leemans, Robert P. Takes, Femke Jansen, and Irma M. Verdonck-de Leeuw. 2023. "Changes in Sexuality and Sexual Dysfunction over Time in the First Two Years after Treatment of Head and Neck Cancer" Cancers 15, no. 19: 4755. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15194755

APA StyleStone, M. A., Lissenberg-Witte, B. I., de Bree, R., Hardillo, J. A., Lamers, F., Langendijk, J. A., Leemans, C. R., Takes, R. P., Jansen, F., & Verdonck-de Leeuw, I. M. (2023). Changes in Sexuality and Sexual Dysfunction over Time in the First Two Years after Treatment of Head and Neck Cancer. Cancers, 15(19), 4755. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15194755