Using Single-Case Experimental Design and Patient-Reported Outcome Measures to Evaluate the Treatment of Cancer-Related Cognitive Impairment in Clinical Practice

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. PROs and Single-Case Experimental Design

1.1.1. PROs

1.1.2. SCED for Clinical Practice: Rationale

- (1)

- (2)

- SCEDs allow for the evaluation of intra-subject variability with multiple assessments before, during, and after the course of treatment, whereas large RCTs typically evaluate less frequently (e.g., baseline, post-treatment, and follow-up). SCEDs thus permit a clearer understanding of the trajectory and timing of treatment response and what factors contribute to response or non-response [39,40,42];

- (3)

- (4)

- SCEDs can provide important clinical information about outcomes that can contribute to the knowledge base of clinical science, especially in rare tumor types, where large RCTs are not easily conducted (e.g., gastrointestinal stromal tumors) [49];

- (5)

- SCED data take less time to be gathered than RCTs, which typically have delays in start-up, completion, and results reporting [50], and SCEDs are less expensive than RCTs.

- (6)

- SCED evaluation can be within a single patient or aggregated across patient cohorts with multiple SCED reports in one or more forms of cancer treatment. For example, examining outcomes of several SCED reports of individuals with CRCI who have undergone chimeric antigen receptor therapy (CAR T-cell) [22]. SCED may also help identify which survivors benefit most, least, or not all from MAAT [26,40] and explore possible related effects of other survivor problems, such as medical or psychological comorbidities [26,32].

1.1.3. SCED Methods and Brief Overview

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. MAAT

2.2. Data Capture

- (1)

- The survivor provides his/her individual e-mail address (an unshared, private account);

- (2)

- The address is entered into a secure link to the REDCap outcomes monitoring system;

- (3)

- REDCap then sends an e-mail to the survivor with a secured link to complete informed written consent (IRB-approved or institutionally approved as a clinical improvement project);

- (4)

- After signed consent is obtained, REDCap presents the survivor with a one-time demographics form assessing variables that could affect MAAT outcomes (e.g., age, type of cancer, year of diagnosis, type of treatment(s), and year of cancer treatment completion). These data can help identify which types of cancer survivors respond to MAAT and can be helpful for clinic management and target resources;

- (5)

- Survivors then complete PROMIS outcome measures via weekly e-mails. No identifying information, such as e-mail address or name, is linked to responses, demographics, or PROMIS measure data. REDCap automatically supplies a digital identifier. This identifier can be used by the clinician to identify and track individual patient outcomes.

2.3. Analyzing, Interpreting, and Reporting Results

- (1)

- Level, or simple quantity of, data in each phase on the vertical axis;

- (2)

- Trend, or slope, in each phase;

- (3)

- Variability within phases;

- (4)

- Overlap or how similar or different scores are between baseline and treatment phases;

- (5)

- Immediacy of Effect, or how rapidly a survivor may improve cognitive function in phase B.

3. Results

3.1. Case Example

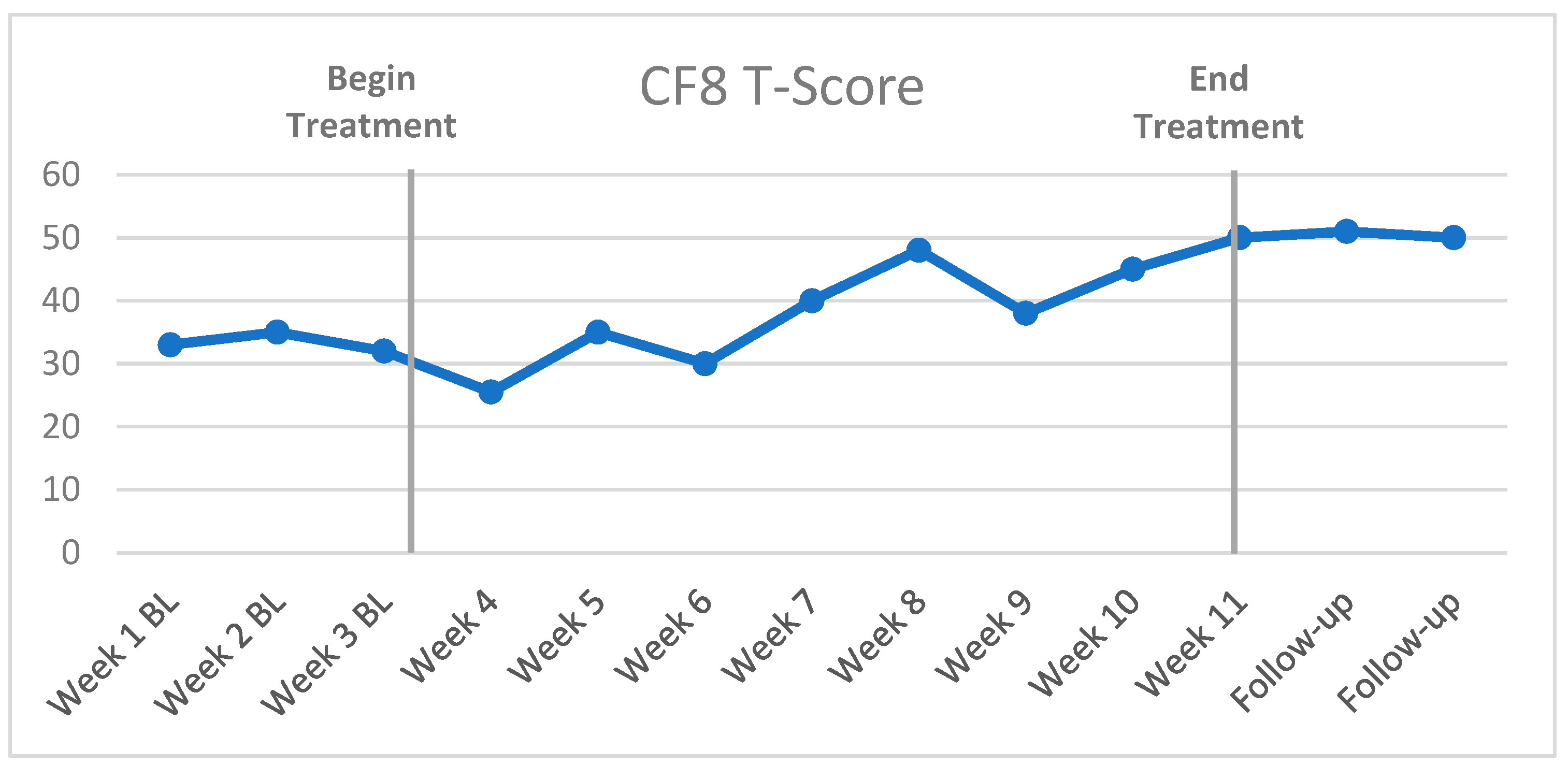

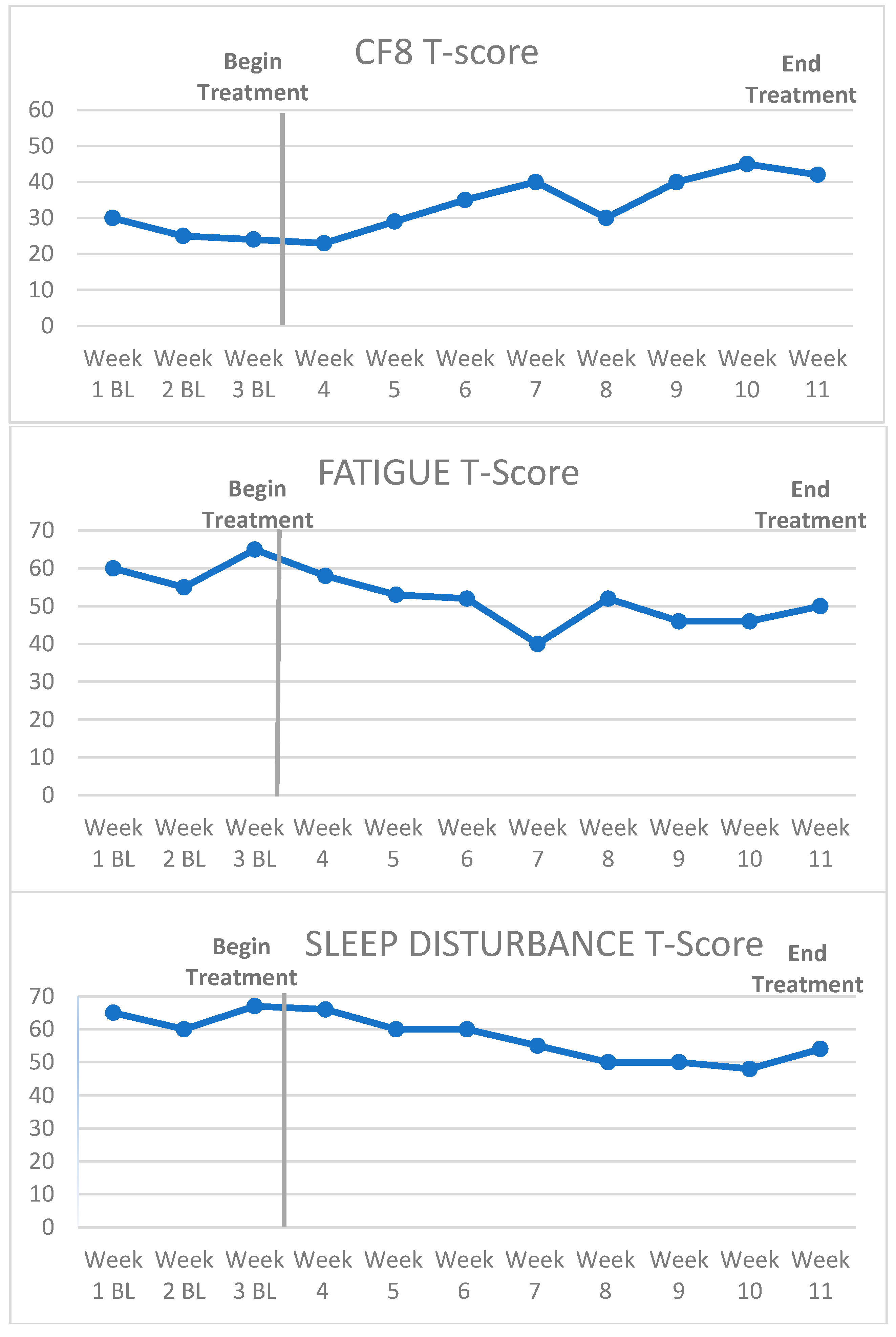

3.2. Visual Inspection and Statistical Analysis of Outcome Data

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wefel, J.S.; Kesler, S.R.; Noll, K.R.; Schagen, S.B. Clinical characteristics, pathophysiology, and management of noncentral nervous system cancer-related cognitive impairment in adults. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2015, 65, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vardy, J.L.; Bray, V.J.; Dhillon, H.M. Cancer-induced cognitive impairment: Practical solutions to reduce and manage the challenge. Future Med. 2017, 13, 767–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boykoff, N.; Moieni, M.; Subramanian, S.K. Confronting chemobrain: An in-depth look at survivors’ reports of impact on work, social networks, and health care response. J. Cancer Surviv. 2009, 3, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, A.K.Y.; Chaidaroon, S.; Fan, G.; Thalib, F. Unintended consequences: The social context of cancer survivors and work. J. Cancer Surviv. 2014, 8, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelblatt, J.S.; Small, B.J.; Luta, G.; Hurria, A.; Jim, H.; McDonald, B.C.; Graham, D.; Zhou, X.; Clapp, J.; Zhai, W. Cancer-Related Cognitive Outcomes Among Older Breast Cancer Survivors in the Thinking and Living with Cancer Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 3211–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janelsins, M.C.; Heckler, C.E.; Peppone, L.J.; Ahles, T.A.; Mohile, S.G.; Mustian, K.M.; Palesh, O.; O’Mara, A.M.; Minasian, L.M.; Williams, A.M. Longitudinal Trajectory and Characterization of Cancer-Related Cognitive Impairment in a Nationwide Cohort Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 3231–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, A.L.; Rowland, J.H.; Ganz, P.A. Life after diagnosis and treatment of cancer in adulthood: Contributions from psychosocial oncology research. Am. Psychol. 2015, 70, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrente, N.C.; Pastor, J.-B.N.; de la Osa Chaparro, N. Systematic review of cognitive sequelae of non-central nervous system cancer and cancer therapy. J. Cancer Surviv. 2020, 14, 464–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, S.J.; Krull, K.R.; Wefel, J.S.; Janelsins, M. Cognitive changes in cancer survivors. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2018, 38, 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.D.; Nogueira, L.; Devasia, T.; Mariotto, A.B.; Yabroff, K.R.; Jemal, A.; Kramer, J.; Siegel, R.L. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 409–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Parkin, D.M.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Bray, F. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: An overview. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 149, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, H.A.; Richard, N.M.; Edelstein, K. Cognitive rehabilitation for cancer-related cognitive dysfunction: A systematic review. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 3253–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahles, T.A.; Saykin, A.J. Candidate mechanisms for chemotherapy-induced cognitive changes. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2007, 7, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, S.J.; Lustberg, M.; Dhillon, H.M.; Nakamura, Z.M.; Allen, D.H.; Von Ah, D.; Janelsins, M.C.; Chan, A.; Olson, K.; Tan, C.J. Cancer-related cognitive impairment in patients with non-central nervous system malignancies: An overview for oncology providers from the MASCC Neurological Complications Study Group. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 2821–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morean, D.F.; O’Dwyer, L.; Cherney, L.R. Therapies for cognitive deficits associated with chemotherapy for breast cancer: A systematic review of objective outcomes. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2015, 96, 1880–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treanor, C.J.; McMenamin, U.C.; O’Neill, R.F.; Cardwell, C.R.; Clarke, M.J.; Cantwell, M.; Donnelly, M. Non-pharmacological interventions for cognitive impairment due to systemic cancer treatment. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2022, CD011325. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y.; Cheng, A.S.; Chan, C.C. Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Neuropsychological Interventions on Cognitive Function in Non–Central Nervous System Cancer Survivors. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2016, 15, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, D.K.; Fanning, J.; Salerno, E.A.; Aguiñaga, S.; Cosman, J.; Severson, J.; Kramer, A.F.; McAuley, E. Replacing sedentary time with physical activity or sleep: Effects on cancer-related cognitive impairment in breast cancer survivors. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Ah, D.; Carpenter, J.S.; Saykin, A.; Monahn, P.; Jingwei, W.; Menggang, Y.; Rebok, G.; Ball, K.; Schneider, B.; Weaver, M.; et al. Advanced cognitive training for breast cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2012, 135, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Ah, D.; Jansen, C.E.; Allen, D.H. Evidence-based interventions for cancer-and treatment-related cognitive impairment. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2014, 18, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schagen, S.B.; Tsvetkov, A.S.; Compter, A.; Wefel, J.S. Cognitive adverse effects of chemotherapy and immunotherapy: Are interventions within reach? Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2022, 18, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.; Lim, C.Y.S.; Dhillon, H.M.; Shaw, J. Australian oncology health professionals’ knowledge, perceptions, and clinical practice related to cancer-related cognitive impairment and utility of a factsheet. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 4729–4738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haywood, D.; Wallace, I.N.; Lawrence, B.; Baughman, F.D.; Dauer, E.; O’Connor, M. Oncology healthcare professionals’ perceptions and experiences of’chemobrain’in cancer survivors and persons undergoing cancer treatment. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2023. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolin, D.F.; McKay, D.; Forman, E.M.; Klonsky, E.D.; Thombs, B.D. Empirically supported treatment: Recommendations for a new model. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2015, 22, 317. [Google Scholar]

- Czajkowski, S.M.; Powell, L.H.; Adler, N.; Naar-King, S.; Reynolds, K.D.; Hunter, C.M.; Laraia, B.; Olster, D.H.; Perna, F.M.; Peterson, J.C. From ideas to efficacy: The ORBIT model for developing behavioral treatments for chronic diseases. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Wang, L.; Bu, X.; Wang, W.; Zhu, J. Unmet supportive care needs of breast cancer survivors: A systematic scoping review. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, R.; Gillock, K. Memory and Attention Adaptation Training: A Brief Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Cancer Survivors. In Clincian Manual; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, R.; Gillock, K. Memory and Attention Adaptation Training: A Brief Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Cancer Survivors. In Survivor Workbook; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, D.; Molloy, S.; Wilkinson, K.; Green, E.; Orchard, K.; Wang, K.; Liberty, J. Patient-reported outcomes in routine cancer clinical practice: A scoping review of use, impact on health outcomes, and implementation factors. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 1846–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Maio, M.; Basch, E.; Denis, F.; Fallowfield, L.; Ganz, P.; Howell, D.; Kowalski, C.; Perrone, F.; Stover, A.; Sundaresan, P. The role of patient-reported outcome measures in the continuum of cancer clinical care: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, 878–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, D.; Nock, M.; Hersen, M. Single Case Experimental Designs: Strategies for Studying Behavior Change, 3rd ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine, T.R.; Weiss, D.M.; Jones, J.A.; Andersen, B.L. Construct validity of PROMIS® Cognitive Function in cancer patients and noncancer controls. Health Psychol. 2019, 38, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, L.I.; Sweet, J.; Butt, Z.; Lai, J.-s.; Cella, D. Measuring patient self-reported cognitive function: Development of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-cognitive function instrument. J. Support. Oncol. 2009, 7, W32–W39. [Google Scholar]

- Fieo, R.; Ocepek-Welikson, K.; Kleinman, M.; Eimicke, J.P.; Crane, P.K.; Cella, D.; Teresi, J.A. Measurement Equivalence of the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System®(PROMIS®) Applied Cognition–General Concerns, Short Forms in Ethnically Diverse Groups. Psychol. Test Assess. Model. 2016, 58, 255. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Draak, T.H.; de Greef, B.T.; Faber, C.G.; Merkies, I.S.; PeriNomS study group. The minimum clinically important difference (MCID): Which direction to take. Eur. J. Neurol. 2019, 26, 850–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.X.; Kroenke, K.; Stump, T.E.; Kean, J.; Carpenter, J.S.; Krebs, E.E.; Bair, M.J.; Damush, T.M.; Monahan, P.O. Estimating minimally important differences for the PROMIS pain interference scales: Results from 3 randomized clinical trials. Pain 2018, 159, 775–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, N.S.; Roberts, L.J.; Berns, S.B.; McGlinchey, J.B. Methods for defining and determining the clinical significance of treatment effects: Description, application, and alternatives. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1999, 67, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, D.H.; Hersen, M. Single Case Experimental Designs; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Tate, R.L.; Perdices, M.; Rosenkoetter, U.; Shadish, W.; Vohra, S.; Barlow, D.H.; Horner, R.; Kazdin, A.; Kratochwill, T.; McDonald, S. The single-case reporting guideline In BEhavioural interventions (SCRIBE) 2016 statement. Evid.-Based Commun. Assess. Interv. 2016, 10, 44–58. [Google Scholar]

- Maggin, D.M.; Briesch, A.M.; Chafouleas, S.M.; Ferguson, T.D.; Clark, C. A comparison of rubrics for identifying empirically supported practices with single-case research. J. Behav. Educ. 2014, 23, 287–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolov, R.; Moeyaert, M. Recommendations for choosing single-case data analytical techniques. Behav. Ther. 2017, 48, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarlow, K.R. An improved rank correlation effect size statistic for single-case designs: Baseline corrected Tau. Behav. Modif. 2017, 41, 427–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, R.I.; Vannest, K.J.; Davis, J.L.; Sauber, S.B. Combining nonoverlap and trend for single-case research: Tau-U. Behav. Ther. 2011, 42, 284–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brossart, D.F.; Laird, V.C.; Armstrong, T.W. Interpreting Kendall’s Tau and Tau-U for single-case experimental designs. Cogent Psychol. 2018, 5, 1518687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Y.T.; Brinkman, T.M.; Li, C.; Mzayek, Y.; Srivastava, D.; Ness, K.K.; Patel, S.K.; Howell, R.M.; Oeffinger, K.C.; Robison, L.L. Chronic health conditions and neurocognitive function in aging survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohr, D.; Burns, M.N.; Schueller, S.M.; Clarke, G.; Klinkman, M. Behavioral intervention technologies: Evidence review and recommendations for future research in mental health. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2013, 35, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliwinski, M.J.; Mogle, J.A.; Hyun, J.; Munoz, E.; Smyth, J.M.; Lipton, R.B. Reliability and validity of ambulatory cognitive assessments. Assessment 2016, 25, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, R.J.; Manculich, J.; Chang, H.; Sareen, N.J.; Snitz, B.E.; Terhorst, L.; Bovbjerg, D.H.; Duensing, A.U. Self-reported cognitive impairments and quality of life in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor: Results of a multinational survey. Cancer 2022, 128, 4017–4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Insel, T.R.; Gogtay, N. NIMH Clinical Trials: Portfolio, Progress to Date, and the Road Forward; NIMH: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tate, R.L.; Perdices, M.; Rosenkoetter, U.; Shadish, W.; Vohra, S.; Barlow, D.H.; Horner, R.; Kazdin, A.; Kratochwill, T.; McDonald, S. The single-case reporting guideline in BEhavioural interventions (SCRIBE) 2016 statement. Aphasiology 2016, 30, 862–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, R.J.; Ahles, T.A.; Saykin, A.J.; McDonald, B.C.; Furstenberg, C.T.; Cole, B.F.; Mott, L.A. Cognitive-behavioral management of chemotherapy-related cognitive change. Psycho-Oncology 2007, 16, 772–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, R.J.; McDonald, B.C.; Rocque, M.A.; Furstenberg, C.T.; Horrigan, S.; Ahles, T.A.; Saykin, A.J. Development of CBT for chemotherapy-related cognitive change: Results of a waitlist control trial. Psycho-Oncology 2012, 21, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, R.; Sigmon, S.T.; Pritchard, A.J.; LaBrie, S.L.; Goetze, R.E.; Fink, C.M.; Garrett, A.M. A randomized trial of videoconference-delivered CBT for survivors of breast cancer with self-reported cognitive dysfunction. Cancer 2016, 122, 1782–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caller, T.A.; Ferguson, R.J.; Roth, R.M.; Secore, K.L.; Alexandre, F.P.; Zhao, W.; Tosteson, T.D.; Henegan, P.L.; Birney, K.; Jobst, B.C. A cognitive behavioral intervention (HOBSCOTCH) improves quality of life and attention in epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2016, 57, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, B.C.; Flashman, L.A.; Arciniegas, D.B.; Ferguson, R.J.; Xing, L.; Harezlak, J.; Sprehn, G.C.; Hammond, F.M.; Maerlender, A.C.; Kruck, C.L. Methylphenidate and memory and attention adaptation training for persistent cognitive symptoms after traumatic brain injury: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 1766–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, R.J.; McDonald, B.C.; Terhorst, L.; Gibbons, B.; Zhao, S.; Bailey, J.; Kreitz, A. Telehealth cognitive-behavioral therapy for cancer-related cognitive impairment: A model for remote clinical trial participation. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, TPS12143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B. Neuropsychological rehabilitation. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 4, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, B.A. Compensating for cognitive deficits following brain injury. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2000, 10, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Heugten, C.M.; Ponds, R.W.; Kessels, R.P. Brain Training: Hype or Hope? Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lustig, C.; Shah, P.; Seidler, R.; Reuter-Lorenz, P. Aging, training, and the brain: A review and future directions. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2009, 19, 504–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohling, M.; Faust, M.; Beverly, B.; Demakis, G. Effectiveness of Cognitive Rehabilitation Following Acquired Brain Injury: A Meta-Analytic Re-Examination of Cicerone et al.’s (2000, 2005) Systematic Reviews. Neuropsychology 2009, 23, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohlberg, M.M.; Matee, C.A. Cognitive Rehabilitation: An Integrative Neuropsychological Appraoch; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, B. The clinical neuropsychologist’s dilemma. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2005, 11, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R.S. Stress and Emotion: A New Synthesis; Springer Publishing Company: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Chan, R.; Deng, Y. Examination of postconcussion-like symptoms in healthy university students: Relationships to subjective and objective neuropsychological function performance. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2006, 21, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iverson, G.; Lange, R. Examination of” postconcussion-like” symptoms in a healthy sample. Appl. Neuropsychol. 2003, 10, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayer, J.; Hansen, A.L.; Saus-rose, E.; Johnsen, B.H. Heart rate variability, prefrontal neural function, and cognitive performance: The neurovisceral integration perspective on self-regulation, adaptation and health. Ann. Behavorial Med. 2009, 37, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patridge, E.F.; Bardyn, T.P. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap). J. Med. Libr. Assoc. JMLA 2018, 106, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunnell, B.E.; Sprague, G.; Qanungo, S.; Nichols, M.; Magruder, K.; Lauzon, S.; Obeid, J.S.; Lenert, L.A.; Welch, B.M. An Exploration of Useful Telemedicine-Based Resources for Clinical Research. Telemed. E-Health 2019, 26, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, C.M.; Qanungo, S.; Jenkins, C.M.; Acierno, R. Technology as a means to address disparities in mental health research: A guide to “tele-tailoring” your research methods. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2018, 49, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, M.A.; Maxwell, R.A. A beginner’s guide to avoiding Protected Health Information (PHI) issues in clinical research–With how-to’s in REDCap Data Management Software. J. Biomed. Inform. 2018, 85, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faden, R.R.; Beauchamp, T.L.; Kass, N.E. Informed consent, comparative effectiveness, and learning health care. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 766–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clapp, J.T.; Fleisher, L.A. What is the Realistic Scope of Informed Consent? Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kass, N.E.; Faden, R.R. Ethics and Learning Health Care: The Essential roles of engagement, transparency, and accountability. Learn. Health Syst. 2018, 2, e10066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarlow, K.R. Basleine Corrected Tau Calculator. Available online: http://www.ktarlow.com/stats/tau (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Wagner, L.I.; Gray, R.J.; Sparano, J.A.; Whelan, T.J.; Garcia, S.F.; Yanez, B.; Tevaarwerk, A.J.; Carlos, R.C.; Albain, K.S.; Olson, J.A., Jr. Patient-reported cognitive impairment among women with early breast cancer randomly assigned to endocrine therapy alone versus chemoendocrine therapy: Results from TAILORx. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekhlyudov, L.; Mollica, M.A.; Jacobsen, P.B.; Mayer, D.K.; Shulman, L.N.; Geiger, A.M. Developing a quality of cancer survivorship care framework: Implications for clinical care, research, and policy. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2019, 111, 1120–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percha, B.; Baskerville, E.B.; Johnson, M.; Dudley, J.; Zimmerman, N. Designing robust N-of-1 studies for precision medicine: Simulation study and design recommendations. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e12641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, F.S.; Varmus, H. A new initiative on precision medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 793–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levit, L.A.; Kim, E.S.; McAneny, B.L.; Nadauld, L.D.; Levit, K.; Schenkel, C.; Schilsky, R.L. Implementing Precision Medicine in Community-Based Oncology Programs: Three Models. J. Oncol. Pract. 2019, 15, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsimberidou, A.M.; Müller, P.; Ji, Y. Innovative trial design in precision oncology. In Seminars in Cancer Biology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 284–292. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, K.; Weinberger, M.; Renfro, C.; Ferreri, S.; Trygstad, T.; Trogdon, J.; Shea, C.M. The role of network ties to support implementation of a community pharmacy enhanced services network. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2019, 15, 1118–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, K.; Nguyen, O.; Hong, Y.-R.; Tabriz, A.A.; Patel, K.; Jim, H.S. Use of electronic health record patient portal accounts among patients with smartphone-only internet access. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2118229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzmaurice, C.; Allen, C.; Barber, R.M.; Barregard, L.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Brenner, H.; Dicker, D.J.; Chimed-Orchir, O.; Dandona, R.; Dandona, L. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 524–548. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ferguson, R.J.; Terhorst, L.; Gibbons, B.; Posluszny, D.M.; Chang, H.; Bovbjerg, D.H.; McDonald, B.C. Using Single-Case Experimental Design and Patient-Reported Outcome Measures to Evaluate the Treatment of Cancer-Related Cognitive Impairment in Clinical Practice. Cancers 2023, 15, 4643. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15184643

Ferguson RJ, Terhorst L, Gibbons B, Posluszny DM, Chang H, Bovbjerg DH, McDonald BC. Using Single-Case Experimental Design and Patient-Reported Outcome Measures to Evaluate the Treatment of Cancer-Related Cognitive Impairment in Clinical Practice. Cancers. 2023; 15(18):4643. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15184643

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerguson, Robert J., Lauren Terhorst, Benjamin Gibbons, Donna M. Posluszny, Hsuan Chang, Dana H. Bovbjerg, and Brenna C. McDonald. 2023. "Using Single-Case Experimental Design and Patient-Reported Outcome Measures to Evaluate the Treatment of Cancer-Related Cognitive Impairment in Clinical Practice" Cancers 15, no. 18: 4643. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15184643

APA StyleFerguson, R. J., Terhorst, L., Gibbons, B., Posluszny, D. M., Chang, H., Bovbjerg, D. H., & McDonald, B. C. (2023). Using Single-Case Experimental Design and Patient-Reported Outcome Measures to Evaluate the Treatment of Cancer-Related Cognitive Impairment in Clinical Practice. Cancers, 15(18), 4643. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15184643