Can Radiomics Provide Additional Information in [18F]FET-Negative Gliomas?

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. [18F]FET PET Imaging

2.3. MR Imaging

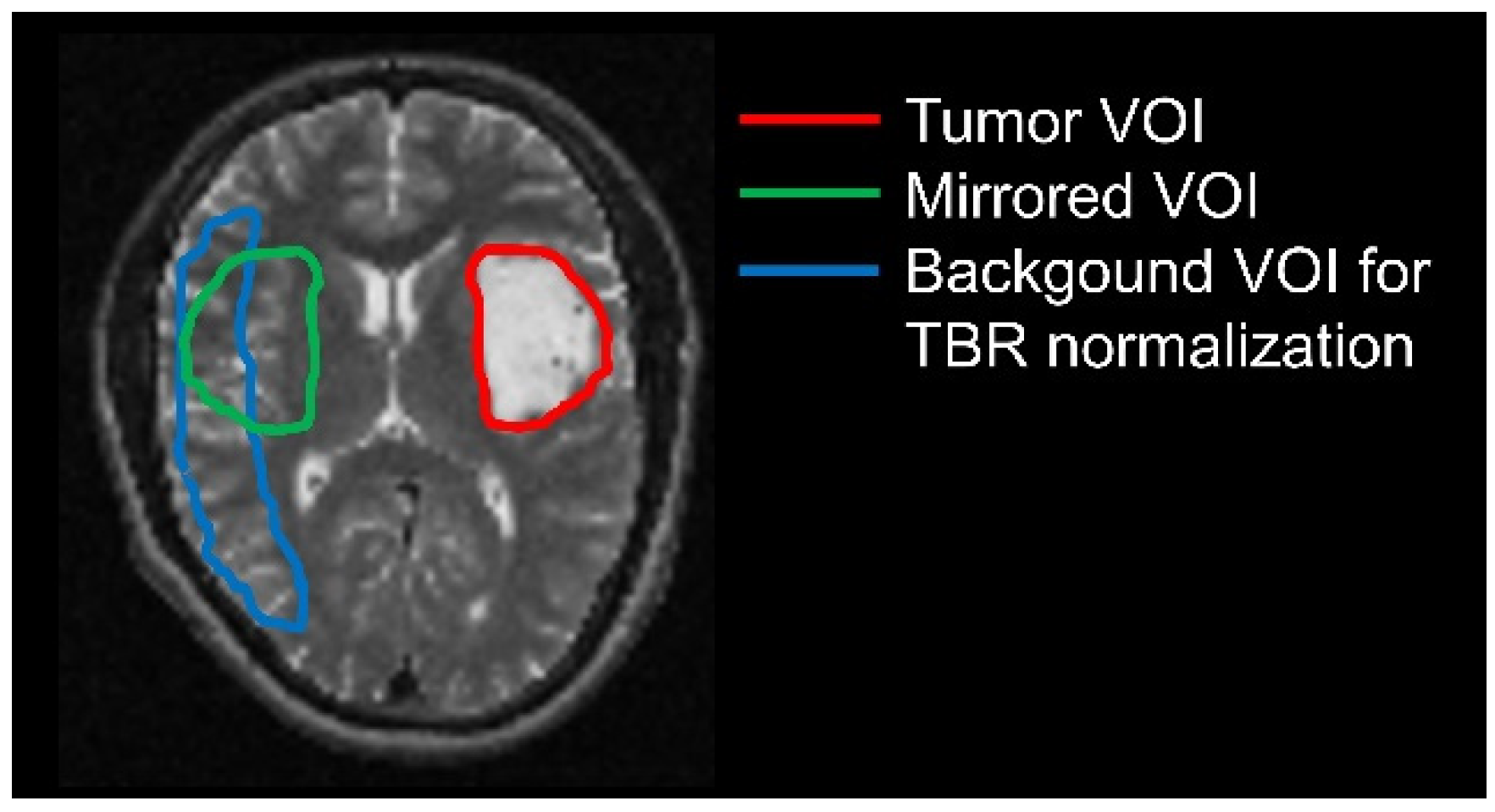

2.4. Delineation of Tumor and Background Volumes

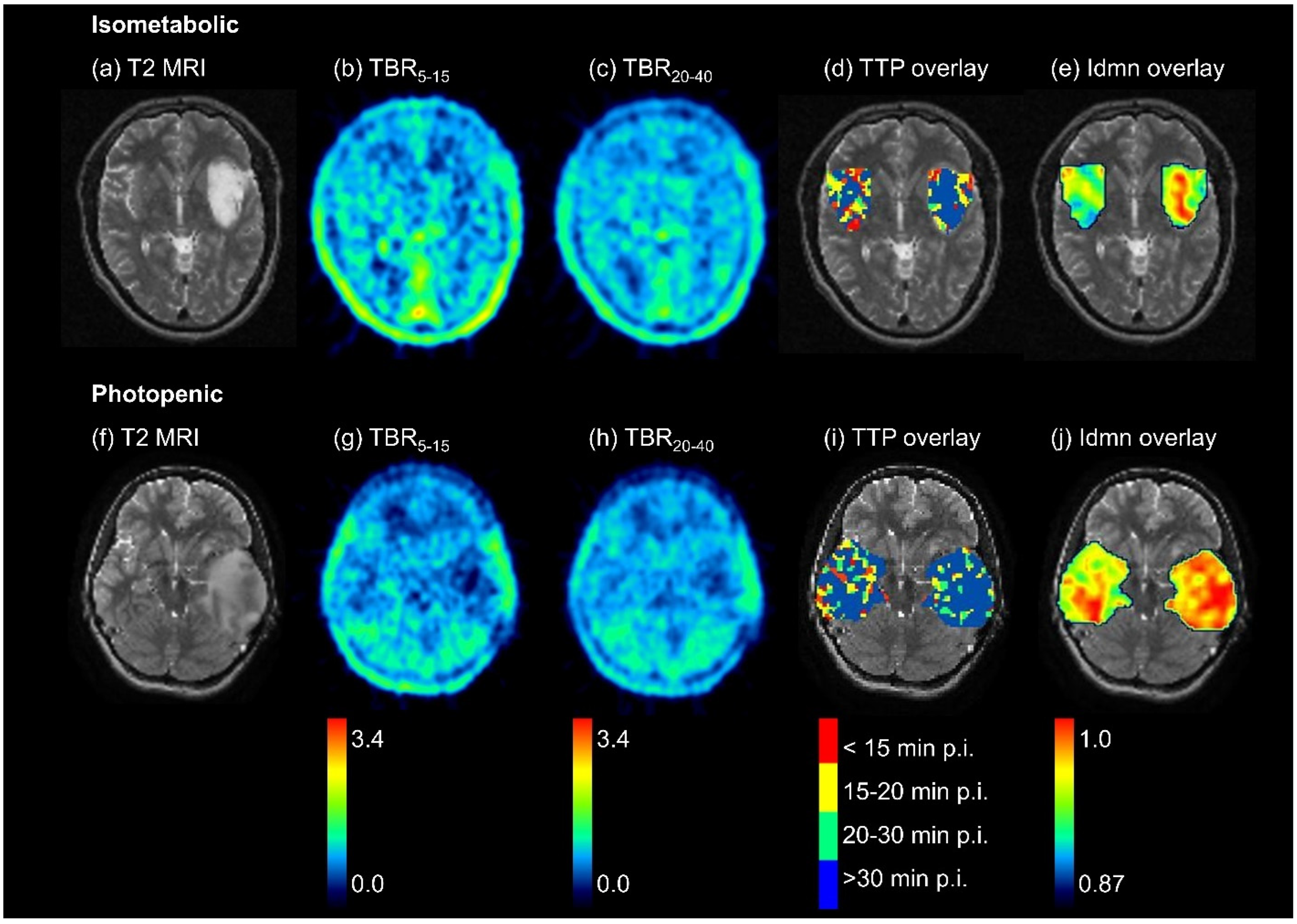

2.5. Generation of Parametric Images

2.6. Extraction of Radiomic Features

2.7. Statistical Analyses

2.8. Differentiation of Tumor from Healthy Tissue Using Logistic Regression

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Differences between [18F]FET-Negative Tumor and Healthy Tissue—Overview

3.3. Differences between Isometabolic Tumor and Healthy Tissue

3.4. Differences between Photopenic Tumor and Healthy Tissue

3.5. Differentiation of Tumor from Healthy Tissue Using Logistic Regression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- la Fougère, C.; Suchorska, B.; Bartenstein, P.; Kreth, F.W.; Tonn, J.C. Molecular imaging of gliomas with PET: Opportunities and limitations. Neuro-Oncol. 2011, 13, 806–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohmann, P.; Stavrinou, P.; Lipke, K.; Bauer, E.K.; Ceccon, G.; Werner, J.M.; Neumaier, B.; Fink, G.R.; Shah, N.J.; Langen, K.J.; et al. FET PET reveals considerable spatial differences in tumour burden compared to conventional MRI in newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2019, 46, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, I.; Albert, N.L.; Arbizu, J.; Boellaard, R.; Drzezga, A.; Galldiks, N.; la Fougere, C.; Langen, K.J.; Lopci, E.; Lowe, V.; et al. Joint EANM/EANO/RANO practice guidelines/SNMMI procedure standards for imaging of gliomas using PET with radiolabelled amino acids and [18F]FDG: Version 1.0. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2019, 46, 540–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floeth, F.W.; Pauleit, D.; Sabel, M.; Stoffels, G.; Reifenberger, G.; Riemenschneider, M.J.; Jansen, P.; Coenen, H.H.; Steiger, H.J.; Langen, K.J. Prognostic value of O-(2-18F-fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine PET and MRI in low-grade glioma. J. Nucl. Med. 2007, 48, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unterrainer, M.; Schweisthal, F.; Suchorska, B.; Wenter, V.; Schmid-Tannwald, C.; Fendler, W.P.; Schüller, U.; Bartenstein, P.; Tonn, J.C.; Albert, N.L. Serial 18F-FET PET Imaging of Primarily 18F-FET-Negative Glioma: Does It Make Sense? J. Nucl. Med. 2016, 57, 1177–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vettermann, F.J.; Diekmann, C.; Weidner, L.; Unterrainer, M.; Suchorska, B.; Ruf, V.; Dorostkar, M.; Wenter, V.; Herms, J.; Tonn, J.C.; et al. L-type amino acid transporter (LAT) 1 expression in (18)F-FET-negative gliomas. EJNMMI Res. 2021, 11, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermeier, A.; Graf, J.; Sandhöfer, B.F.; Boissel, J.P.; Roesch, F.; Closs, E.I. System L amino acid transporter LAT1 accumulates O-(2-fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine (FET). Amino Acids 2015, 47, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galldiks, N.; Unterrainer, M.; Judov, N.; Stoffels, G.; Rapp, M.; Lohmann, P.; Vettermann, F.; Dunkl, V.; Suchorska, B.; Tonn, J.C.; et al. Photopenic defects on O-(2-[18F]-fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine PET: Clinical relevance in glioma patients. Neuro-Oncol. 2019, 21, 1331–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmann, P.; Elahmadawy, M.A.; Gutsche, R.; Werner, J.M.; Bauer, E.K.; Ceccon, G.; Kocher, M.; Lerche, C.W.; Rapp, M.; Fink, G.R.; et al. FET PET Radiomics for Differentiating Pseudoprogression from Early Tumor Progression in Glioma Patients Post-Chemoradiation. Cancers 2020, 12, 3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmann, P.; Meissner, A.K.; Kocher, M.; Bauer, E.K.; Werner, J.M.; Fink, G.R.; Shah, N.J.; Langen, K.J.; Galldiks, N. Feature-based PET/MRI radiomics in patients with brain tumors. Neurooncol. Adv. 2020, 2, iv15–iv21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, R.J.; Kinahan, P.E.; Hricak, H. Radiomics: Images Are More than Pictures, They Are Data. Radiology 2016, 278, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Kaiser, L.; Holzgreve, A.; Ruf, V.C.; Suchorska, B.; Wenter, V.; Quach, S.; Herms, J.; Bartenstein, P.; Tonn, J.-C.; et al. Prediction of TERTp-mutation status in IDH-wildtype high-grade gliomas using pre-treatment dynamic [18F]FET PET radiomics. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2021, 48, 4415–4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohmann, P.; Lerche, C.; Bauer, E.K.; Steger, J.; Stoffels, G.; Blau, T.; Dunkl, V.; Kocher, M.; Viswanathan, S.; Filss, C.P.; et al. Predicting IDH genotype in gliomas using FET PET radiomics. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Wesseling, P.; Brat, D.J.; Cree, I.A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Hawkins, C.; Ng, H.K.; Pfister, S.M.; Reifenberger, G.; et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A summary. Neuro-Oncol. 2021, 23, 1231–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eigenbrod, S.; Trabold, R.; Brucker, D.; Erös, C.; Egensperger, R.; La Fougere, C.; Göbel, W.; Rühm, A.; Kretzschmar, H.A.; Tonn, J.C.; et al. Molecular stereotactic biopsy technique improves diagnostic accuracy and enables personalized treatment strategies in glioma patients. Acta Neurochir. 2014, 156, 1427–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig, K.; Kornblum, H.I. Molecular markers in glioma. J. Neurooncol. 2017, 134, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, N.L.; Graute, V.; Armbruster, L.; Suchorska, B.; Lutz, J.; Eigenbrod, S.; Cumming, P.; Bartenstein, P.; Tonn, J.C.; Kreth, F.W.; et al. MRI-suspected low-grade glioma: Is there a need to perform dynamic FET PET? Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2012, 39, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vomacka, L.; Unterrainer, M.; Holzgreve, A.; Mille, E.; Gosewisch, A.; Brosch, J.; Ziegler, S.; Suchorska, B.; Kreth, F.W.; Tonn, J.C.; et al. Voxel-wise analysis of dynamic 18F-FET PET: A novel approach for non-invasive glioma characterisation. EJNMMI Res. 2018, 8, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unterrainer, M.; Vettermann, F.; Brendel, M.; Holzgreve, A.; Lifschitz, M.; Zähringer, M.; Suchorska, B.; Wenter, V.; Illigens, B.M.; Bartenstein, P.; et al. Towards standardization of (18)F-FET PET imaging: Do we need a consistent method of background activity assessment? EJNMMI Res. 2017, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwanenburg, A.; Leger, S.; Vallières, M.; Löck, S. Image biomarker standardisation initiative. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1612.07003. [Google Scholar]

- Haubold, J.; Demircioglu, A.; Gratz, M.; Glas, M.; Wrede, K.; Sure, U.; Antoch, G.; Keyvani, K.; Nittka, M.; Kannengiesser, S.; et al. Non-invasive tumor decoding and phenotyping of cerebral gliomas utilizing multiparametric 18F-FET PET-MRI and MR Fingerprinting. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2020, 47, 1435–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohmann, P.; Stoffels, G.; Ceccon, G.; Rapp, M.; Sabel, M.; Filss, C.P.; Kamp, M.A.; Stegmayr, C.; Neumaier, B.; Shah, N.J.; et al. Radiation injury vs. recurrent brain metastasis: Combining textural feature radiomics analysis and standard parameters may increase (18)F-FET PET accuracy without dynamic scans. Eur. Radiol. 2017, 27, 2916–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohmann, P.; Kocher, M.; Ceccon, G.; Bauer, E.K.; Stoffels, G.; Viswanathan, S.; Ruge, M.I.; Neumaier, B.; Shah, N.J.; Fink, G.R.; et al. Combined FET PET/MRI radiomics differentiates radiation injury from recurrent brain metastasis. Neuroimage Clin. 2018, 20, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyka, T.; Gempt, J.; Hiob, D.; Ringel, F.; Schlegel, J.; Bette, S.; Wester, H.J.; Meyer, B.; Forster, S. Textural analysis of pre-therapeutic [18F]-FET-PET and its correlation with tumor grade and patient survival in high-grade gliomas. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2016, 43, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kickingereder, P.; Sahm, F.; Radbruch, A.; Wick, W.; Heiland, S.; Deimling, A.; Bendszus, M.; Wiestler, B. IDH mutation status is associated with a distinct hypoxia/angiogenesis transcriptome signature which is non-invasively predictable with rCBV imaging in human glioma. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, V.C.; Gielen, G.H.; Pintea, B.; Baumgarten, P.; Datsi, A.; Hittatiya, K.; Simon, M.; Hattingen, E. DCE-MRI in Glioma, Infiltration Zone and Healthy Brain to Assess Angiogenesis: A Biopsy Study. Clin. Neuroradiol. 2021, 31, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh Thong, P.; Minh Duc, N. The Role of Apparent Diffusion Coefficient in the Differentiation between Cerebellar Medulloblastoma and Brainstem Glioma. Neurol. Int. 2020, 12, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss, A.; Pan, L.; Sachpekidis, C. Parametric Imaging With Dynamic PET for Oncological Applications: Protocols, Interpretation, Current Applications and Limitations for Clinical Use. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2022, 52, 312–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, E.; Cherry, S.R.; Wang, G. Total-body PET kinetic modeling and potential opportunities using deep learning. PET Clin. 2021, 16, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Image | Whole Cohort (n = 46) | Isometabolic (n = 29) | Photopenic (n = 17) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TBR20–40 | 5 (5%) | 11 (12%) | 19 (20%) |

| TBR5–15 | 14 (15%) | 3 (3%) | 25 (27%) |

| TTP | 64 (69%) | 64 (69%) | 24 (26%) |

| Included features | Whole Cohort | Isometabolic | Photopenic |

|---|---|---|---|

| TBR20–40 | 0.54 ± 0.14 | 0.55 ± 0.15 | 0.66 ± 0.20 |

| TBR5–15 | 0.65 ± 0.13 | 0.56 ± 0.13 | 0.79 ± 0.17 |

| TTP | 0.61 ± 0.12 | 0.64 ± 0.14 | 0.55 ± 0.20 |

| All | 0.64 ± 0.13 | 0.67 ± 0.15 | 0.80 ± 0.20 |

| Univariate | 0.69 ± 0.12 | 0.72 ± 0.14 | 0.86 ± 0.15 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

von Rohr, K.; Unterrainer, M.; Holzgreve, A.; Kirchner, M.A.; Li, Z.; Unterrainer, L.M.; Suchorska, B.; Brendel, M.; Tonn, J.-C.; Bartenstein, P.; et al. Can Radiomics Provide Additional Information in [18F]FET-Negative Gliomas? Cancers 2022, 14, 4860. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14194860

von Rohr K, Unterrainer M, Holzgreve A, Kirchner MA, Li Z, Unterrainer LM, Suchorska B, Brendel M, Tonn J-C, Bartenstein P, et al. Can Radiomics Provide Additional Information in [18F]FET-Negative Gliomas? Cancers. 2022; 14(19):4860. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14194860

Chicago/Turabian Stylevon Rohr, Katharina, Marcus Unterrainer, Adrien Holzgreve, Maximilian A. Kirchner, Zhicong Li, Lena M. Unterrainer, Bogdana Suchorska, Matthias Brendel, Joerg-Christian Tonn, Peter Bartenstein, and et al. 2022. "Can Radiomics Provide Additional Information in [18F]FET-Negative Gliomas?" Cancers 14, no. 19: 4860. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14194860

APA Stylevon Rohr, K., Unterrainer, M., Holzgreve, A., Kirchner, M. A., Li, Z., Unterrainer, L. M., Suchorska, B., Brendel, M., Tonn, J.-C., Bartenstein, P., Ziegler, S., Albert, N. L., & Kaiser, L. (2022). Can Radiomics Provide Additional Information in [18F]FET-Negative Gliomas? Cancers, 14(19), 4860. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14194860