The Impact of Vulvar Cancer on Psychosocial and Sexual Functioning: A Literature Review

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

3. Results

| Category | Studies | Country | Mean Age | Type of Surgery | Measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of life | Blbulyan et al., 2020 [25] | Russia | 56.3 | - | EORTC; FACT-G | Lower overall quality of life. Restrictions in physical activity, poorer social interaction and emotional sphere. Worse global health status. |

| de Melo Ferreira et al., 2012 [26] | Brazil | 66.9 | Vulvectomy + IFL | EORTC | ||

| Farrel et al., 2014 [27] | Australia | 63 | IFL | UBQC | ||

| Gane et al., 2018 [28] | Australia | 57 | Vulvectomy with or without SNB or IFL | FACT-G | ||

| Günther et al., 2014 [29] | Germany | 63 WLE–59 RV | WLE or radical vulvectomy with or without IFL | EORTC | ||

| Hellinga et al., 2018 [30] | Netherlands | 65.5 | WLE/radical vulvectomy/pelvic exenteration + reconstruction with lotus petal flap | EORTC | ||

| Janda et al., 2004 [18] | Australia | 68.8 | WLE or radical vulvectomy with or without IFL | ECOG-PSR; FACT-G | ||

| Jones et al., 2016 [31] | UK | 59.9 | WLE or radical vulvectomy with or without IFL | EORTC | ||

| Likes et al., 2007 [32] | USA | 47.5 | WLE | EORTC | ||

| Oonk et al., 2009 [20] | Netherlands | 69 | WLE or radical vulvectomy with SNB or IFL | EORTC | ||

| Novackova et al., 2012 [33] | Czech Republic | 66.5 CONS–73.8 RAD | WLE or radical vulvectomy with SNB or IFL | EORTC | ||

| Senn et al., 2013 [34] | Germany | 18 (VIN) 42 (K) | Laser vaporisation/WLE/vulvectomy/radical vulvectomy/exenteration with or without SNB or IFL | WOMAN-PRO | ||

| Weijmar Schultz et al., 1990 [35] | Netherlands | 55 | WLE or radical vulvectomy with or without IFL | ad hoc questionnaire | ||

| Trott et al., 2020 [36] | Germany | 63 | Unspecified vulvar surgery with or without SNB or IFL with or without reconstruction | EORTC | ||

| Partner relationship | Aerts et al., 2014 [37] | Belgium | 57.4 | Vulvectomy with or without SNB | DAS | Lower quality of partner relationship, marital satisfaction and dyadic cohesion. |

| Barlow et al., 2014 [38] | Australia | 58 | Radical partial or total vulvectomy with or without IFL | clinical interview | ||

| Sexual Functioning | Aerts et al., 2014 [37] | Belgium | 57.4 | Vulvectomy with or without SNB | SFSS; SSPQ | Worse sexual functioning. Disruption and reduction in sexual activity. |

| Andersen et al., 1983 [24] | USA | 55 | WLE or radical vulvectomy | SCL-90 | ||

| Andersen et al., 1988 [39] | USA | 50.3 | Laser vaporisation/WLE/vulvectomy | DSFI; SAI | ||

| Andreasson et al., 1986 [40] | Denmark | 45.8 | Vulvectomy | ad hoc questionnaire | ||

| Barlow et al., 2014 [38] | Australia | 58 | Radical partial or total vulvectomy with or without IFL | clinical interview | ||

| Blbulyan et al., 2020 [25] | Russia | 56.3 | - | FSFI | ||

| Farrel et al., 2014 [27] | Australia | 63 | IFL | clinical information | ||

| Green et al., 2000 [41] | USA | 60 | Vulvectomy with or without IFL | ad hoc questionnaire | ||

| Grimm et al., 2016 [42] | Germany | 51.5 | Laser vaporisation/WLE/radical vulvectomy | FSFI | ||

| Hazewinkel et al., 2012 [43] | Netherlands | 68 | WLE or radical vulvectomy with or without SNB or IFL | FSFI; BIS | ||

| Hellinga et al., 2018 [30] | Netherlands | 65.5 | WLE/radical vulvectomy/pelvic exenteration + reconstruction with lotus petal flap | FSFI; BIS | ||

| Jones et al., 2016 [31] | UK | 59.9 | WLE or radical vulvectomy with or without IFL | clinical interview | ||

| Weijmar Schultz et al., 1990 [35] | Netherlands | 55 | WLE or radical vulvectomy with or without IFL | ad hoc questionnaire | ||

| Likes et al., 2007 [32] | USA | 47.5 | WLE | FSFI | ||

| Psychological health | Aerts et al., 2014 [37] | Belgium | 57.4 | Vulvectomy with or without sentinel node dissection | BDI | Presence of depressive and anxious symptoms, worsened by altered body image and sexual difficulties. Impact on general well-being, quality of life, and relationship with partner and families. |

| Avery et al., 1974 [44] | USA | NA | Vulvectomy | clinical information | ||

| Andersen et al., 1983 [24] | USA | 55 | WLE or radical vulvectomy | BDI | ||

| Andreasson et al., 1986 [40] | Denmark | 45.8 | Vulvectomy | ad hoc questionnaire | ||

| Corney et al., 1992 [45] | UK | 71% >65 | Radical vulvectomy, Wertheim’s hysterectomy or pelvic exenteration | HADS; clinical interview | ||

| Green et al., 2000 [41] | USA | 60 | Vulvectomy with or without IFL | PRIME-MD | ||

| Janda et al., 2004 [18] | Australia | 68.8 | WLE or radical vulvectomy with or without IFL | FACT-G; HADS | ||

| Jefferies and Clifford, 2012 [46] | UK | >50 | - | clinical interview | ||

| McGrath et al., 2013 [47] | Australia | NA | - | clinical interview | ||

| Senn et al., 2011 [48] | Germany | 55 | Laser vaporisation/WLE/radical vulvectomy with or without SNB or IFL | clinical interview | ||

| Senn et al., 2013 [34] | Germany | 18 (VIN) 42 (K) | Laser vaporisation/WLE/vulvectomy/radical vulvectomy/exenteration with or without SNB or IFL | WOMAN-PRO | ||

| Stellman et al., 1984 [49] | USA | 53.4 | Vulvectomy or radical vulvectomy | SQ | ||

| Tamburini et al., 1986 [19] | Italy | 51.7 | Vulvectomy with or without IFL | clinical interview | ||

| Thuesen et al., 1992 [50] | Denmark | 41.4 | WLE | clinical interview; ad hoc questionnaire |

3.1. Psychological Impact

3.2. Quality of Life, Sexuality and Partner Relationship

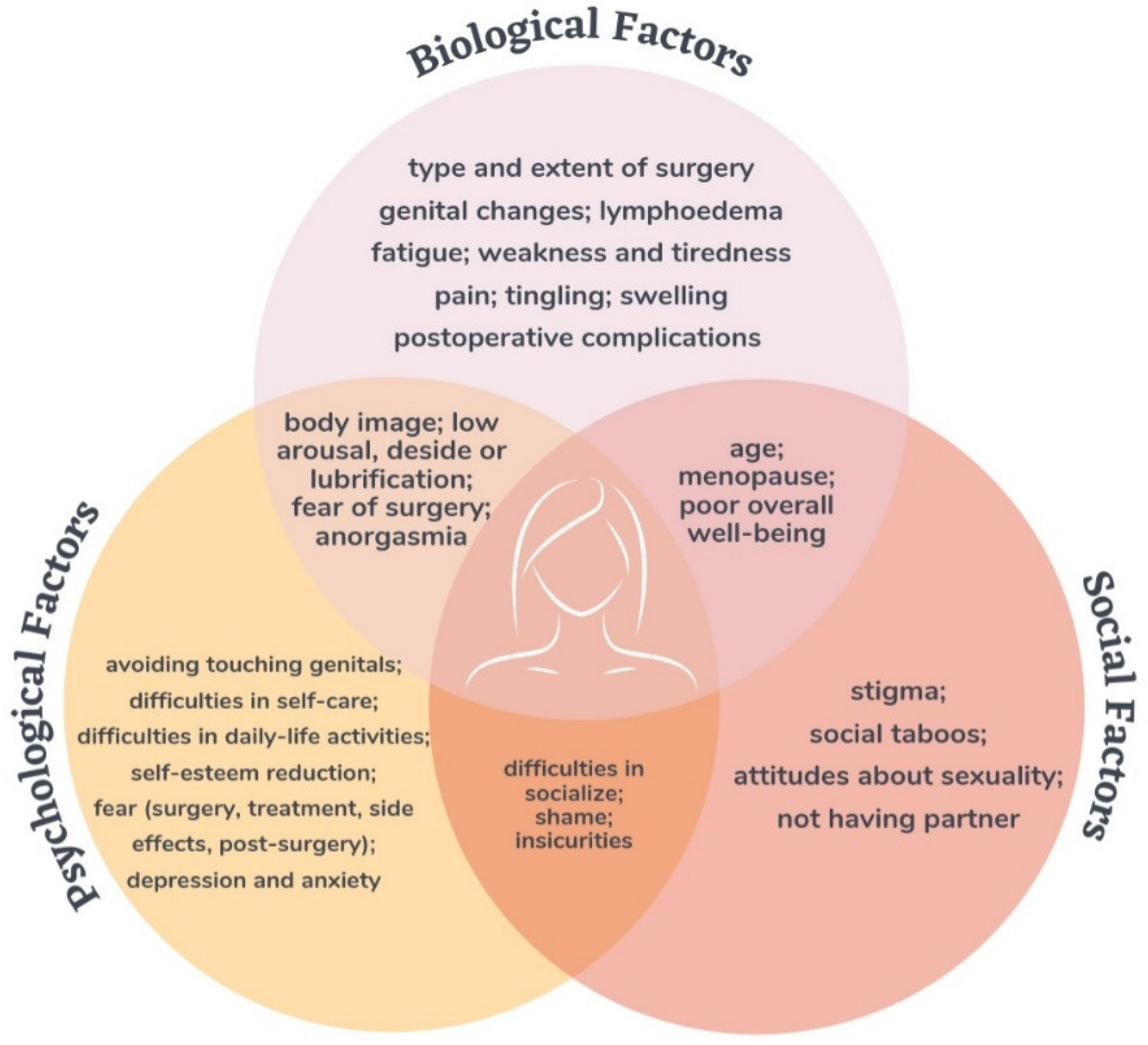

Related Bio–Psycho–Social Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Future Research

4.2. Implications for Clinical Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 7–34. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.3322/caac.21551 (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- National Cancer Institute. The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. About the SEER Program. 2014. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/about/ (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- Stroup, A.; Harlan, L.; Trimble, E. Demographic, clinical, and treatment trends among women diagnosed with vulvar cancer in the United States. Gynecol. Oncol. 2008, 108, 577–583. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0090825807009195 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joura, E.A.; Lösch, A.; Haider-Angeler, M.G.; Breitenecker, G.; Leodolter, S. Trends in vulvar neoplasia. Increasing incidence of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva in young women. J. Reprod. Med. 2000, 45, 613–615. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10986677 (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- Van der Avoort, I.A.M.; Shirango, H.; Hoevenaars, B.M.; Grefte, J.M.M.; de Hullu, J.A.; de Wilde, P.C.M.; Bulten, J.; Melchers, W.; Massuger, L.F.A.G. Vulvar Squamous Cell Carcinoma is a Multifactorial Disease Following Two Separate and Independent Pathways. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2006, 25, 22–29. Available online: http://journals.lww.com/00004347-200601000-00002 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Nieuwenhof, H.P.; van Kempen, L.C.; de Hullu, J.A.; Bekkers, R.L.; Bulten, J.; Melchers, W.J.; Massuger, L.F. The Etiologic Role of HPV in Vulvar Squamous Cell Carcinoma Fine Tuned. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2009, 18, 2061–2067. Available online: http://cebp.aacrjournals.org/lookup/doi/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0209 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Handisurya, A.; Schellenbacher, C.; Kirnbauer, R. Diseases caused by human papillomaviruses (HPV). J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2009, 7, 453–466. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1610-0387.2009.06988.x (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornstein, J.; Bogliatto, F.; Haefner, H.K.; Stockdale, C.K.; Preti, M.; Bohl, T.G.; Reutter, J.; ISSVD Terminology Committee. The 2015 International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) Terminology of Vulvar Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2016, 20, 11–14. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/00128360-201601000-00003 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preti, M.; Selk, A.; Stockdale, C.; Bevilacqua, F.; Vieira-Baptista, P.; Borella, F.; Gallio, N.; Cosma, S.; Melo, C.; Micheletti, L.; et al. Knowledge of Vulvar Anatomy and Self-examination in a Sample of Italian Women. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2021, 25, 166–171. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/10.1097/LGT.0000000000000585 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellinger, T.H.; Hakim, A.A.; Lee, S.J.; Wakabayashi, M.T.; Morgan, R.J.; Han, E.S. Surgical Management of Vulvar Cancer. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2016, 15, 121–128. Available online: https://jnccn.org/doi/10.6004/jnccn.2017.0009 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- DiSaia, P.J.; Creasman, W.T.; Rich, W.M. An alternate approach to early cancer of the vulva. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1979, 133, 825–832. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0002937879901194 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Heaps, J.M.; Fu, Y.S.; Montz, F.J.; Hacker, N.F.; Berek, J.S. Surgical-pathologic variables predictive of local recurrence in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Gynecol. Oncol. 1990, 38, 309–314. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/009082589090064R. (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Höckel, M.; Dornhöfer, N. Vulvovaginal reconstruction for neoplastic disease. Lancet Oncol. 2008, 9, 559–568. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1470204508701475 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Stehman, F.B.; Bundy, B.N.; Ball, H.; Clarke-Pearson, D.L. Sites of failure and times to failure in carcinoma of the vulva treated conservatively: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996, 174, 1128–1133. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0002937896706543 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Covens, A.; Vella, E.T.; Kennedy, E.B.; Reade, C.J.; Jimenez, W.; Le, T. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in vulvar cancer: Systematic review, meta-analysis and guideline recommendations. Gynecol. Oncol. 2015, 137, 351–361. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S009082581500654X (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, H.C.; Ansink, A.; Verhaar-Langereis, M.M.; Stalpers, L.L. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation for advanced primary vulvar cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006, CD003752. Available online: https://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD003752.pub2 (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- Aerts, L.; Enzlin, P.; Vergote, I.; Verhaeghe, J.; Poppe, W.; Amant, F. Sexual, Psychological, and Relational Functioning in Women after Surgical Treatment for Vulvar Malignancy: A Literature Review. J. Sex. Med. 2012, 9, 361–371. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1743609515338522 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janda, M.; Obermair, A.; Cella, D.; Crandon, A.J.; Trimmel, M. Vulvar cancer patients’ quality of life: A qualitative assessment. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2004, 14, 875–881. Available online: https://ijgc.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1111/j.1048-891X.2004.14524.x (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamburini, M.; Filiberti, A.; Ventafridda, V.; de Palo, G. Quality of Life and Psychological State after Radical Vulvectomy. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 1986, 5, 263–269. Available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3109/01674828609016766 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Oonk, M.; van Os, M.; de Bock, G.; de Hullu, J.; Ansink, A.; van der Zee, A. A comparison of quality of life between vulvar cancer patients after sentinel lymph node procedure only and inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy. Gynecol. Oncol. 2009, 113, 301–305. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0090825808010561 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ayhan, A.; Tuncer, Z.S.; Akarin, R.; Yücel, I.; Develioǧlu, O.; Mercan, R.; Zeyneloǧlu, H. Complications of radical vulvectomy and inguinal lymphadenectomy for the treatment of carcinoma of the vulva. J. Surg. Oncol. 1992, 51, 243–245. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1434654/ (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balat, O.; Edwards, C.; Delclos, L. Complications following combined surgery (radical vulvectomy versus wide local excision) and radiotherapy for the treatment of carcinoma of the vulva: Report of 73 patients. Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2000, 21, 501–503. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11198043 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [PubMed]

- Gaarenstroom, K.N.; Kenter, G.G.; Trimbos, J.B.; Agous, I.; Amant, F.; Peters, A.A.W.; Vergote, I. Postoperative complications after vulvectomy and inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy using separate groin incisions. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2003, 13, 522–527. Available online: https://ijgc.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1046/j.1525-1438.2003.13304.x (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, B.L.; Hacker, N.F. Psychosexual adjustment after vulvar surgery. Obstet. Gynecol. 1983, 62, 457–462. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6888823 (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- Blbulyan, T.A.; Solopova, A.G.; Ivanov, A.E.; Kurkina, E.I. Effect of postoperative rehabilitation on quality of life in patients with vulvar cancer. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. 2020, 14, 415–425. Available online: https://www.gynecology.su/jour/article/view/790 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.P.D.M.; de Figueiredo, E.M.; Lima, R.A.; Cândido, E.B.; Monteiro, M.V.D.C.; Franco, T.M.R.D.F.; Traiman, P.; da Silva-Filho, A.L. Quality of life in women with vulvar cancer submitted to surgical treatment: A comparative study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2012, 165, 91–95. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0301211512002941 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, R.; Gebski, V.; Hacker, N.F. Quality of Life After Complete Lymphadenectomy for Vulvar Cancer: Do Women Prefer Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy? Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2014, 24, 813–819. Available online: https://ijgc.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1097/IGC.0000000000000101 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gane, E.M.; Steele, M.L.; Janda, M.; Ward, L.C.; Reul-Hirche, H.; Carter, J.; Quinn, M.; Obermair, A.; Hayes, S.C. The Prevalence, Incidence, and Quality-of-Life Impact of Lymphedema After Treatment for Vulvar or Vaginal Cancer. Rehabil. Oncol. 2018, 36, 48–55. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/01893697-201801000-00008 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Günther, V.; Malchow, B.; Schubert, M.; Andresen, L.; Jochens, A.; Jonat, W.; Mundhenke, C.; Alkatout, I. Impact of radical operative treatment on the quality of life in women with vulvar cancer—A retrospective study. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 40, 875–882. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0748798314003941 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellinga, J.; Grootenhuis, N.C.T.; Werker, P.M.; de Bock, G.H.; van der Zee, A.G.; Oonk, M.H.; Stenekes, M.W. Quality of Life and Sexual Functioning After Vulvar Reconstruction with the Lotus Petal Flap. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2018, 28, 1728–1736. Available online: https://ijgc.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1097/IGC.0000000000001340 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.L.; Jacques, R.M.; Thompson, J.; Wood, H.J.; Hughes, J.; Ledger, W.; Alazzam, M.; Radley, S.C.; Tidy, J.A. The impact of surgery for vulval cancer upon health-related quality of life and pelvic floor outcomes during the first year of treatment: A longitudinal, mixed methods study. Psycho-Oncology 2016, 25, 656–662. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pon.3992 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Likes, W.M.; Stegbauer, C.; Tillmanns, T.; Pruett, J. Correlates of sexual function following vulvar excision. Gynecol. Oncol. 2007, 105, 600–603. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0090825807000510 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Novackova, M.; Halaska, M.J.; Robova, H.; Mala, I.; Pluta, M.; Chmel, R.; Rob, L. A Prospective Study in Detection of Lower-Limb Lymphedema and Evaluation of Quality of Life After Vulvar Cancer Surgery. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2012, 22, 1081–1088. Available online: https://ijgc.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1097/IGC.0b013e31825866d0 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senn, B.; Eicher, M.; Mueller, M.; Hornung, R.; Fink, D.; Baessler, K.; Hampl, M.; Denhaerynck, K.; Spirig, R.; Engberg, S. A patient-reported outcome measure to identify occurrence and distress of post-surgery symptoms of WOMen with vulvAr Neoplasia (WOMAN-PRO)—A cross sectional study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2013, 129, 234–240. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S009082581200995X (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Weijmar Schultz, W.C.M.; van de Wiel, H.B.M.; Bouma, J.; Janssens, J.; Littlewood, J. Psychosexual functioning after the treatment of cancer of the vulva: A longitudinal study. Cancer 1990, 66, 402–407. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/1097-0142(19900715)66:2%3C402::AID-CNCR2820660234%3E3.0.CO;2-X (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Trott, S.; Höckel, M.; Dornhöfer, N.; Geue, K.; Aktas, B.; Wolf, B. Quality of life and associated factors after surgical treatment of vulvar cancer by vulvar field resection (VFR). Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 302, 191–201. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00404-020-05584-5 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Aerts, L.; Enzlin, P.; Verhaeghe, J.; Vergote, I.; Amant, F. Psychologic, Relational, and Sexual Functioning in Women After Surgical Treatment of Vulvar Malignancy: A Prospective Controlled Study. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2014, 24, 372–380. Available online: https://ijgc.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1097/IGC.0000000000000035 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlow, E.L.; Hacker, N.F.; Hussain, R.; Parmenter, G. Sexuality and body image following treatment for early-stage vulvar cancer: A qualitative study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 1856–1866. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jan.12346 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, B.L.; Turnquist, D.; Lapolla, J.; Turner, D. Sexual functioning after treatment of in situ vulvar cancer: Preliminary report. Obstet. Gynecol. 1988, 71, 15–19. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3336539 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [PubMed]

- Andreasson, B.; Moth, I.; Jensen, S.B.; Bock, J.E. Sexual Function and Somatopsychic Reactions in Vulvectomy-Operated Women and their Partners. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 1986, 65, 7–10. Available online: http://doi.wiley.com/10.3109/00016348609158221 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, M.S.; Naumann, R.; Elliot, M.; Hall, J.B.; Higgins, R.V.; Grigsby, J.H. Sexual Dysfunction Following Vulvectomy. Gynecol. Oncol. 2000, 77, 73–77. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0090825800957457 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Grimm, D.; Eulenburg, C.; Brümmer, O.; Schliedermann, A.-K.; Trillsch, F.; Prieske, K.; Gieseking, F.; Selka, E.; Mahner, S.; Woelber, L. Sexual activity and function after surgical treatment in patients with (pre)invasive vulvar lesions. Support. Care Cancer 2015, 24, 419–428. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00520-015-2812-8 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazewinkel, M.H.; Laan, E.T.; Sprangers, M.A.; Fons, G.; Burger, M.P.; Roovers, J.-P.W. Long-term sexual function in survivors of vulvar cancer: A cross-sectional study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2012, 126, 87–92. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0090825812002703 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Avery, W.; Gardner, C.; Palmer, S. Vulvectomy. Am. J. Nurs. 1974, 74, 453–455. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4492906 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [PubMed]

- Corney, R.; Everett, H.; Howells, A.; Crowther, M. Psychosocial adjustment following major gynaecological surgery for carcinoma of the cervix and vulva. J. Psychosom. Res. 1992, 36, 561–568. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/002239999290041Y (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Jefferies, H.; Clifford, C. Invisibility: The lived experience of women with cancer of the vulva. Cancer Nurs. 2012, 35, 382–389. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/00002820-201209000-00008 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- McGrath, P.; Rawson, N. Key factors impacting on diagnosis and treatment for vulvar cancer for Indigenous women: Findings from Australia. Support. Care Cancer 2013, 21, 2769–2775. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00520-013-1859-7 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senn, B.; Gafner, D.; Happ, M.; Eicher, M.; Mueller, M.; Engberg, S.; Spirig, R. The unspoken disease: Symptom experience in women with vulval neoplasia and surgical treatment: A qualitative study. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2011, 20, 747–758. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01267.x (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Stellman, R.E.; Goodwin, J.M.; Robinson, J.; Dansak, D.; Hilgers, R.D. Psychological effects of vulvectomy. J. Psychosom. Res. 1984, 25, 779–783. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0033318284729653 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Thuesen, B.; Andreasson, B.; Bock, J.E. Sexual function and somatopsychic reactions after local excision of vulvar intra-epithelial neoplasia. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 1992, 71, 126–128. Available online: http://doi.wiley.com/10.3109/00016349209007969 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Jefferies, H.; Clifford, C. A literature review of the impact of a diagnosis of cancer of the vulva and surgical treatment. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20, 3128–3142. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03728.x (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janda, M.; Obermair, A.; Cella, D.; Perrin, L.; Nicklin, J.; Gordon-Ward, B.; Crandon, A.J.; Trimmel, M. The functional assessment of cancer-vulvar: Reliability and validity. Gynecol. Oncol. 2005, 97, 568–575. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0090825805001137 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boden, J.; Willis, S. The psychosocial issues of women with cancer of the vulva. J. Radiother. Pract. 2019, 18, 93–97. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S1460396918000420/type/journal_article (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Niedzwiedz, C.L.; Knifton, L.; Robb, K.A.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Smith, D.J. Depression and anxiety among people living with and beyond cancer: A growing clinical and research priority. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 943. Available online: https://bmccancer.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12885-019-6181-4 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Walker, J.; Hansen, C.H.; Martin, P.; Sawhney, A.; Thekkumpurath, P.; Beale, C.; Symeonides, S.; Wall, L.; Murray, G.; Sharpe, M. Prevalence of depression in adults with cancer: A systematic review. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 895–900. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0923753419371893 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-H.; Li, J.-Q.; Shi, J.-F.; Que, J.-Y.; Liu, J.-J.; Lappin, J.; Leung, J.; Ravindran, A.V.; Chen, W.-Q.; Qiao, Y.-L.; et al. Depression and anxiety in relation to cancer incidence and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 25, 1487–1499. Available online: http://www.nature.com/articles/s41380-019-0595-x (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Y.; Li, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Leng, M.; Chen, L. Depression and cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health 2017, 149, 138–148. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0033350617301737 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Board, C.N.E. Vulvar Cancer: Statistics. Available online: https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/vulvar-cancer/statistics (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- Baziliansky, S.; Cohen, M. Emotion regulation and psychological distress in cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Stress Health 2021, 37, 3–18. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/smi.2972 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Mokhatri-Hesari, P.; Montazeri, A. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: Review of reviews from 2008 to 2018. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 1–25. Available online: https://hqlo.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12955-020-01591-x (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faria, B.M.; Rodrigues, I.M.; Marquez, L.V.; Pires, U.D.S.; de Oliveira, S.V. The impact of mastectomy on body image and sexuality in women with breast cancer: A systematic review. Psicooncología 2021, 18, 91–115. Available online: https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/PSIC/article/view/74534 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-C.; Chang, S.-R.; Chiu, S.-C. Sexual Problems of Patients with Breast Cancer After Treatment. Cancer Nurs. 2019, 42, 418–425. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000592 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valente, M.; Chirico, I.; Ottoboni, G.; Chattat, R. Relationship Dynamics among Couples Dealing with Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7288. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/14/7288 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandão, T.; Pedro, J.; Nunes, N.; Martins, M.; Costa, M.E.; Matos, P.M. Marital adjustment in the context of female breast cancer: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncol. 2017, 26, 2019–2029. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pon.4432 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fradgley, E.A.; Bultz, B.D.; Kelly, B.J.; Loscalzo, M.J.; Grassi, L.; Sitaram, B. Progress toward integrating Distress as the Sixth Vital Sign: A global snapshot of triumphs and tribulations in precision supportive care. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. Res. Pract. 2019, 1, e2. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/jporp/Fulltext/2019/07000/Progress_toward_integrating_Distress_as_the_Sixth.2.aspx (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Sopfe, J.; Pettigrew, J.; Afghahi, A.; Appiah, L.; Coons, H. Interventions to Improve Sexual Health in Women Living with and Surviving Cancer: Review and Recommendations. Cancers 2021, 13, 3153. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6694/13/13/3153 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elit, L.; Reade, C.J. Recommendations for Follow-up Care for Gynecologic Cancer Survivors. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 126, 1207–1214. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/00006250-201512000-00014 (accessed on 30 October 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Malandrone, F.; Bevilacqua, F.; Merola, M.; Gallio, N.; Ostacoli, L.; Carletto, S.; Benedetto, C. The Impact of Vulvar Cancer on Psychosocial and Sexual Functioning: A Literature Review. Cancers 2022, 14, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14010063

Malandrone F, Bevilacqua F, Merola M, Gallio N, Ostacoli L, Carletto S, Benedetto C. The Impact of Vulvar Cancer on Psychosocial and Sexual Functioning: A Literature Review. Cancers. 2022; 14(1):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14010063

Chicago/Turabian StyleMalandrone, Francesca, Federica Bevilacqua, Mariagrazia Merola, Niccolò Gallio, Luca Ostacoli, Sara Carletto, and Chiara Benedetto. 2022. "The Impact of Vulvar Cancer on Psychosocial and Sexual Functioning: A Literature Review" Cancers 14, no. 1: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14010063

APA StyleMalandrone, F., Bevilacqua, F., Merola, M., Gallio, N., Ostacoli, L., Carletto, S., & Benedetto, C. (2022). The Impact of Vulvar Cancer on Psychosocial and Sexual Functioning: A Literature Review. Cancers, 14(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14010063