Simple Summary

Most patients diagnosed with primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) are 60 years or older and tend to have a poor prognosis. Evidence to guide and optimize treatment choices for these vulnerable patients is limited. We performed a scoping review to identify and describe all relevant clinical studies investigating chemotherapies and combinations of chemotherapies (including high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (HCT-ASCT)) in elderly PCNSL patients. In total, we identified six randomized controlled trials, 26 prospective and 24 retrospective studies (with/without control group). While most studies investigated protocols based on ‘conventional’ chemotherapy treatment, data evaluating HCT-ASCT in the elderly were scarce, and the generalizability of the only RCT published is questionable. Considering the poor prognosis of these patients and their need for more effective treatment options, a thoroughly planned randomized controlled trial comparing HCT-ASCT with ‘conventional’ chemoimmunotherapy is urgently needed to evaluate the efficacy of HCT-ASCT.

Abstract

Background: Most patients diagnosed with primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) are older than 60 years. Despite promising treatment options for younger patients, prognosis for the elderly remains poor and efficacy of available treatment options is limited. Materials and Methods: We conducted a scoping review to identify and summarize the current study pool available evaluating different types and combinations of (immuno) chemotherapy with a special focus on HCT-ASCT in elderly PCNSL. Relevant studies were identified through systematic searches in the bibliographic databases Medline, Web of Science, Cochrane Library and ScienceDirect (last search conducted in September 2020). For ongoing studies, we searched ClinicalTrials.gov, the German study register and the WHO registry. Results: In total, we identified six randomized controlled trials (RCT) with 1.346 patients, 26 prospective (with 1.366 patients) and 24 retrospective studies (with 2.629 patients). Of these, only six studies (one completed and one ongoing RCT (with 447 patients), one completed and one ongoing prospective single arm study (with 65 patients), and two retrospective single arm studies (with 122 patients)) evaluated HCT-ASCT. Patient relevant outcomes such as progression-free and overall survival and (neuro-)toxicity were adequately considered across almost all studies. The current study pool is, however, not conclusive in terms of the most effective treatment options for elderly. Main limitations were (very) small sample sizes and heterogeneous patient populations in terms of age ranges (particularly in RCTs) limiting the applicability of the results to the target population (elderly). Conclusions: Although it has been shown that HCT-ASCT is probably a feasible and effective treatment option, this approach has never been investigated within a RCT including a wide range of elderly patients. A RCT comparing conventional (immuno) chemotherapy with HCT-ASCT is crucial to evaluate benefit and harms in an un-biased manner to eventually provide older PCNSL patients with the most effective treatment.

1. Introduction

Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the central nervous system (PCNSL) is an orphan disease with an age-adjusted annual incidence rate of seven cases per million in the United States [1]. The Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States (CBTRUS) 2011–2015 report estimates that PCNSL represents approximately 1.9% of all primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors and 6.3% of malignant CNS tumors [2]. Elderly patients (>60 years) are more commonly affected and the incidence is increasing [3].

More than 90% of PCNSL cases are of the diffuse large B-cell type [4] and the majority of which have ≥ 1 mutations in the NF-kB and B-cell receptor signaling pathways, such as CD79B, MYD88, TBL1XR1, CARD11, or CDKN2A [5]. Furthermore, PCNSL frequently show immunoglobulin rearrangement, specifically IGHV4-34 [6]. Based on their immunophenotype and gene expression, PCNSL in immunocompetent patients share features of late germinal center and activated post–germinal center B-cells [7,8,9,10].

PCNSL risk is highly elevated among patients with acquired immunosuppression [11]. In immunosuppressed patients, PCNSL is frequently associated with ineffective immunoregulation of EBV-associated B-cell proliferation and high rates of Epstein-Barr-Virus (EBV) positivity. Conversely, only 5–15% of immunocompetent PCNSL are EBV positive [12]. EBV-associated PCNSL significantly differs from EBV-negative disease as it is typically absent of CD79B and MYD88 mutations and is rarely ABC cell of origin [13]. Importantly, although the CNS is an immune-privileged niche under physiological conditions, PCNSL frequently contain a strong inflammatory response [14]. The extent to which age-specific differences might arise with regard to the characteristics described above has not been shown to date.

Unlike many brain tumors, the typical disease history of patients with PCNSL extends only over a short period of a few weeks. Frequently, patients are noted for personality changes, memory or language deficits, neuropsychiatric symptoms, or focal neurologic deficits. Less common initial symptoms include uveitis, seizures, or increased intracranial pressure [15]. The majority of PCNSL patients initially present with only a singular focus of lymphoma, whereas disseminated, multifocal forms of disease are much rarer [16] and approximately 15% of patients present with ocular involvement at initial diagnosis [17]. Older age should not obviate establishment of a diagnosis. Stereotactic biopsy is the standard of care to obtain a histological diagnosis [18].

PCNSL patients frequently suffer a high burden of disease with various neurological symptoms leading to rapid clinical deterioration and death if not immediately treated. Thus, patients with PCNSL in general, and in particular elderly patients, require high resources for obtaining optimal age- and comorbidity-adapted treatment management during their often multiple hospital stays [19]. Additionally, older patients have an inferior prognosis compared to younger patients [20,21] and are more seriously affected by treatment toxicity, especially neurotoxicity (following treatment with whole brain radiotherapy (WBRT)) accompanied by dementia, ataxia, gait disturbances, and incontinence) [22]. Thus, treatment decisions in elderly PCNSL patients must be individualized, taking into account pre-morbid performance status and comorbidities. Importantly, age alone should not be a barrier for delivery of an intensive treatment regimen if patients appear to have adequate physiological fitness [23].

The current treatment standard for newly diagnosed (elderly) PCNSL patients is high-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX)-based immuno-chemotherapy [24,25,26,27,28]. Consolidation treatment is typically used to prolong remission after induction therapy. Commonly used consolidation strategies comprise non-myeloablative chemotherapy [29], WBRT, or high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (HCT-ASCT) [30,31]. The rationale behind HCT-ASCT in PCNSL is to increase the treatment concentration by a multiple factor to support diffusion across the blood brain barrier, resulting in penetration into the CNS—which cannot be achieved with conventionally dosed therapy. In younger patients, HCT-ASCT has become the most widely accepted consolidation approach. Two RCTs [32,33] and various single arm studies [34,35,36,37,38,39] investigated thiotepa-based HCT-ASCT protocols in PCNSL patients younger than 65 and 70 years of age, with 4-year overall survival (OS) rates over 80% [32]. However, elderly (PCNSL) patients often fail to receive optimal treatment due to lacking evidence from clinical studies.

Recently, HCT-ASCT has been increasingly used in selected elderly PCNSL patients who are able to tolerate aggressive systemic chemotherapy. Nevertheless, an optimal approach regarding treatment intensification-particularly in elderly PCNSL patients- needs to be established. To overcome this challenge it is important to identify the eligible elderly patient population with newly diagnosed PCNSL tolerating more intense and shorter HCT-ASCT treatment protocols and hence benefit from this treatment option (i.e., patients who improve in efficacy outcomes without increasing toxicity).

We aimed to summarize the current study pool available evaluating different types and combinations of chemotherapy with a special focus on HCT-ASCT in elderly PCNSL patients by using the methods of a scoping review [40]. The results of this scoping review are an important part of the conceptual development phase for a planned prospective international, multicenter randomized controlled trial investigating the efficacy and safety of “HCT-ASCT in comparison to conventional chemotherapy with the rituximab-MTX-procarbazine (R-MP) protocol followed by procarbazine maintenance in elderly patients with newly diagnosed PCNSL” (prospective registration identifier of the clinical trial: DRKS DRKS00024085).

The scoping review will explore the different chemotherapy-containing treatment protocols in elderly PCNSL patients investigated in RCTs and non-randomized clinical studies (including one-arm studies), the exact eligibility criteria of the populations included in the studies, the diagnostic methods used for defining eligibility for different treatment approaches, and the outcomes reported. Outcomes of interest will be progression-free survival (PFS), event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS), remission rates and toxicity parameters. The results of the scoping review will highlight areas where clinical studies are lacking. Furthermore, the review will support us to finalize and adjust the research protocol (including the design and methodology) of the planned randomized controlled trial by our team (PRIMA-CNS trial).

2. Materials and Methods

This scoping review was registered at OSF (registration DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/ZPCNU). Comprehensive systematic literature searches for relevant studies were conducted according to PRESS (Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies) guidelines [41]. These searches were performed by an information specialist without any date restrictions. The initial systematic search with an explicit focus on HCT-ASCT in PCNSL was conducted on 29 May 2020 in the electronic data sources Medline, Medline Daily Update, Medline In Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Medline Epub Ahead of Print (via Ovid)), Web of Science Core Collection (Science Citation Index-EXPANDED), Cochrane Library (via Wiley), and ScienceDirect (via Elsevier). The second search (with a broader focus regarding the intervention, i.e., with the focus on any type and combination of chemotherapy) was conducted on 8 September 2020 in Medline, Medline Daily Update, Medline In Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Medline Epub Ahead of Print (via Ovid; Table S2). The reason for the second broader search was that potentially relevant studies were not identified by limiting the intervention to HCT-ASCT only. Therefore, we conducted this additional search focused on any type or combination of chemotherapy in elderly PCNSL patients (our population of interest). Searches for ongoing or unpublished completed studies were performed in ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov, accessed on 5 June 2020) and the German study register (www.drks.de, accessed on 5 June 2020). We used relevant studies and/or systematic reviews to search for additional references via the Pubmed similar articles function (https://www.nlm.nih.gov/bsd/disted/pubmedtutorial/020_190.html, accessed on 5 June 2020) and forward citation tracking using the Web of Science Core Collection. Furthermore, reference lists of relevant studies and systematic reviews were scanned for potentially relevant studies not captured by other searches.

Titles and abstracts of the references identified by the searches were screened by one reviewer (B.N.) and full texts of all potentially relevant articles were obtained. Full texts were checked for final eligibility and reasons for exclusions were documented. The screening process was conducted in Covidence (www.covidence.org, accessed on 5 June 2020).

Studies including immunocompetent PCNSL patients aged 60 years or older (≥60) receiving any therapy line were included. Studies including younger patients (aged < 60 years) or patients with mixed ages (</≥60 years) without providing subgroup analysis for older ages (≥60) as well as those including immunocompromised patients with PCNSL were excluded. All types, doses and combinations of chemotherapy-based treatment regimen including HCT-ASCT were considered.

Randomized controlled trials, non-randomized studies of interventions including studies in which individuals are allocated to different interventions using methods that are not random; observational studies and single arm studies were considered, whereas case reports, review articles, work without peer-review and results reported in abstract form only were excluded. No exclusion criteria regarding study duration were applied.

Key study data including, characteristics of the participants, characteristics of the intervention, characteristics of the comparator, outcomes and their definitions were extracted and relevant information tabulated. Data from each included study were extracted by 1 reviewer (B.N.) and checked by a second (C.S.). Disagreements were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached.

3. Results

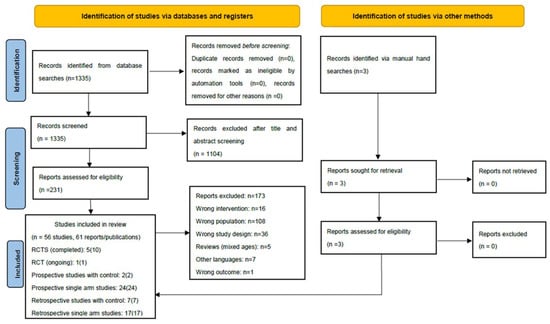

Overall, 1335 records were identified by our systematic searches, of which 234 were considered for full-text assessment. In total, 56 studies corresponding to 61 publications full-filled the inclusion criteria for the scoping review. The PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) outlines the screening and selection process of these articles. Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 and Table S1 present the key characteristics and main outcomes of the identified six RCTs, two prospective non-randomized studies (with control group), 24 prospective single arm studies (including one protocol for an ongoing study) and 24 retrospective studies (seven with control group and 17 single arm studies).

Figure 1.

Results of the bibliographic literature searches and study 198 selection (PRISMA 2020 flow diagram). RCT: randomized controlled trial. From: [42] For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/, accessed on 11 August 2021.

Table 1.

Key characteristics of randomized controlled trials.

Table 2.

Outcomes considered and design aspects in the randomized trials including protocol.

Table 3.

Key characteristics of prospective, non-randomized studies including efficacy and toxicity outcomes.

3.1. Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs)

3.1.1. Key Characteristics of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs)

The key characteristics of the six RCTs (five completed, one ongoing [MATRix trial]) are displayed in Table 1.

RCTs Comparing Different Types of Chemotherapy (N = 2)

Setting, follow-up: Two RCTs compared different types of chemotherapy; the multicenter and multinational, open-label phase III study conducted by Bromberg et al. and the multicenter Phase II study authored by Omuro et al. The latter recruited 95 patients between the years 2007 and 2010 and was conducted at 13 centers in France with a median follow-up time of 32 months (interquartile range [IQR] 26–36) [43]. Bromberg et al. randomized 200 participants across 23 centers in the Netherlands, Australia, and New Zealand. The study recruited participants between 2010 and 2016 with a median follow-up time of 32.9 months (IQR 24–52) [44].

Definition of patient population: Both RCTs included immunocompetent patients with newly diagnosed PCNSL confirmed histologically and/or with neuroimaging. While the study of Omuro et al. is the only trial specifically designed for elderly PCNSL patients (60 years or older, Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) of 40 or more), Bromberg et al. included (younger) patients up to the age of 70 years (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) between 0 and 3)). In Omuro et al., median age was 73 years (range 60–85) in the intervention and 72 years (range 60–84) in the control group. Bromberg et al. reported a median of 61 years (range 55–67) in the intervention and 61 years (range 56–66) in the control group, respectively.

Treatment protocol: In Bromberg et al., all patients were treated with a chemotherapy backbone comprising two 28-day-cycles of HD-MTX 3 g/m2/day for 2 days, carmustine 100 mg/m2 once, teniposide 100 mg/m2/day for 2 days, prednisone 60 mg/m2/day for 6 days and consolidating cytarabine (AraC) 2 × 2 g/m2 for 2 days. Half of the patients (N = 100) were randomized to additionally receive the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab 375 mg/m2/for 4 days in cycle 1 and 2 days in cycle 2 (intervention group). Importantly, the treatment regimen of younger patients differed from that of elderly patients with regard to consolidation treatment. In responding patients, consolidating WBRT with 20 fractions of 1.5 Gray (Gy) with an additional integrated boost to the tumor bed of 20 fractions of 0.5 Gy in patients with only partial remission (PR) was applied in a subgroup of patients aged ≤ 60 years whereas patients > 60 years did not receive additional treatment [44].

Within their randomized trial specifically designed for elderly PCNSL patients, Omuro et al. compared two different chemotherapy combination regimen of different intensity. Forty-eight patients received three 28-day-cycles of HD-MTX 3.5 g/m2/day for two days in combination with the oral alkylating agent temozolomide 150 mg/m2/day for five days (intervention group). Forty-seven patients received three 28-day-cycles of polyagent chemotherapy with HD-MTX 3.5 g/m2/day for 2 days, procarbazine 100 mg/m2/day for 8 days, vincristine 1.4 mg/m2/d for 2 days and consolidating AraC 3g/m2/day for 2 days (control group) [45].

RCT Comparing Chemotherapy with WBRT vs. Chemotherapy Alone (N = 1)

Setting, follow-up: The multicenter phase III trial of the German PCNSL Study Group (G-PCNSL-SG-1 trial) was conducted across 75 German centers. Participants were recruited between the years 2000 and 2009 [46]. In the context of this trial, there were a total of five reports published [24,46,47,48,49], resulting in different follow-up times with a maximum median follow-up time of 81.2 months. A subgroup analysis for patients > 60 years was provided. Additionally, within a post-hoc analysis, the study population of the G-PCNSL-SG-1 trial was divided arbitrarily into two age groups with a cut-off of 70 years or older. Within this post-hoc analysis, outcome data for 126 patients > 70 years was reported [24].

Definition of patient population: Overall, 551 immunocompetent patients with newly diagnosed, histologically proven PCNSL were included without age limitations. However, patients with KPS less than 50% for reasons not related to PCNSL, and of less than 30% for reasons related to PCNSL were excluded. Median age of the two groups was 62 (SD 10.8) (intervention group) and 61 years (SD 11.6) (control group).

Treatment protocol: Patients included in the G-PCNSL-SG-1 trial received six 14-day cycles of HD-MTX 4 g/m2 (in the further course of the trial ifosfamide 1.5 g/m2/d for 3 days was added) with or without randomly assigned WBRT consolidation treatment with a total dose of 45 Gy. Those patients who were allocated to treatment without WBRT and who did not achieve complete remission (CR) were given four cycles of high-dose AraC (HD-AraC) 3 g/m2 twice daily for 2 days.

RCTs Comparing Chemotherapy with WBRT vs. WBRT Alone (N = 1)

Setting, follow-up: The phase II study by Mead et al. was conducted across 12 centers in the United Kingdom between 1988 and 1995. Recruitment was stopped prematurely through poor accrual. Fifty-three previously untreated, immunocompetent adult patients with pathologically proven PCNSL were randomized between WBRT with or without previous polychemotherapy treatment. Each randomized group included patients > 60 years (WBRT + chemotherapy N = 17; WBRT N = 3). Median follow-up was 60 months (range 12–108) [50].

Definition of patient population: In the trial by Mead et al. adults without any limitations regarding age and ECOG PS were included but patients with neurologic status (Medical Research Council Neurological Scale of 3 or less) were excluded.

Treatment protocol: Patients were randomly assigned to receive six 21-day cycles of post-surgery and -radiotherapy chemotherapy treatment with cyclophosphamide 750 mg/m2, doxorubicin 50 mg/m2, vincristine 1.4 mg/m2 and prednisone 20 mg/d for 5 days (CHOP) vs. no additional chemotherapy treatment.

RCTs Evaluating HCT-ASCT (N = 2, Results Not Applicable for Elderly or Pending)

Setting, follow-up:

The phase II International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group (IELSG32) trial was the first reported trial directly comparing HCT-ASCT with WBRT. The trial (by Ferreri et al.) was conducted across 53 centers in five European countries [32,51]. From 2010 to 2014, a total of 227 patients with newly diagnosed PCNSL up to 70 years were included. Median age across the groups ranged between 58 and 57 years, with a median follow-up time of 40 months. The first randomization compared different induction chemotherapy regimens [51]. The second randomization compared HCT-ASCT with WBRT and considered 118 patients (see below) [32].

The subsequent ongoing MATRix/IELSG43 trial is conducted in 5 European countries [29]. Within this randomized phase III RCT, 220 patients are randomized (after induction treatment with the MATRix protocol) between consolidating HCT-ASCT and ‘conventional’ consolidating treatment. Recruitment was completed in August 2019, follow-up is ongoing and results are expected in 2022.

Definition of patient population: In the IELSG32 and in the MATRix/IELSG43 trial, patients were eligible after the following criteria: (i) ≤65 years with ECOG PS ≤ 3 and (ii) up to the age of 70 years only with ECOG PS ≤ 2.

Treatment protocol: Within the IELSG32 trial by Ferreri et al. induction treatment consisted of different intensity (depending on the treatment arm). Those patients randomly assigned to arm A received four 21-day-cycles of HD-MTX 3.5 g/m2 once and AraC 2 g/m2 twice daily for 2 days, patients assigned to arm B additionally received the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab 375 mg/m2 twice, whereas patients assigned to arm C received the combination of arm B plus thiotepa 30 mg/m2 once (so called MATRix regimen). Patients achieving stable or responsive disease were again randomly assigned to consolidation treatment with either WBRT (36 Gy with an additional nine Gy tumor-bed boost in patients with partial response, N = 59 patients) or HCT with carmustine 400 mg/m2 once and thiotepa 5 mg/kg twice a day for 2 days followed by ASCT (N = 59 patients) (second randomization). Within the subsequent (still ongoing) MATRix/IELSG43 trial, four 21-day-cycles of the MATRix regimen were administered followed by randomization between consolidating HCT-ASCT with carmustine 400 mg/m2 once and thiotepa 5 mg/kg twice a day for 2 days or conventional consolidating treatment with rituximab 375 g/m2 once, dexamethasone 40 mg/d for 3 days, etoposide 100 mg/m2/d for 3 days, ifosfamide 1500 mg/m2/d for 3 days and carboplatin 300 mg/m2 once (R-DeVIC protocol) in responding patients.

3.1.2. Outcomes of the Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs)

Table 2 provides an overview of the outcomes considered and main results of the five completed randomized trials.

RCTs Comparing Different Types of Chemotherapy (N = 2)

Bromberg et al. reported event-free survival (EFS) as the primary outcome. Events were defined as the absence of (unconfirmed) complete remission (CR) at the end of protocol treatment, or relapse or death after previous (unconfirmed) CR (according to the International PCNSL Collaborative Group (IPCG) Response Criteria [18]). Overall, the authors reported that outcomes were not different within the two treatment groups. For example, one-year EFS was 52% (95% CI 42–61) in the patients who additionally received rituximab (intervention group) and 49% (95% CI 39–58) in the chemotherapy arm without rituximab (control group). Notably, additional WBRT after chemoimmunotherapy was only administered to younger patients (≤60 years). Subgroup analysis showed that younger patients (≤60 years) had better results in terms of EFS when rituximab was added (intervention group; median EFS 59.9 months (95% CI 41.4–not reached)) compared to the control group (median EFS 19.7 months (95% CI 6.5–not reached) (HR 0.56, 95% CI 0.31–1.01, p = 0.054). In the subgroup for older patients (>60 years) no difference between the treatment arms was observed [44]. However, these findings have to be interpreted with caution, as consolidation strategy with WBRT varied significantly between these age groups.

The RCT by Omuro et al. reported one-year progression-free survival (PFS) as primary outcome. PFS was defined as time to progression (determined by local investigators) or death. Secondary outcomes were overall survival (OS), toxicity, objective response, quality of life (QoL) and neuropsychological evaluation. One-year PFS was 36% (95% CI 22–50) in both groups, but OS and response rates favored the more intensive treatment group (control group). No differences in toxicity between the study groups were observed. Importantly, QoL improved across most domains in comparison to baseline in both groups without evidence of late neurotoxicity (using prospective neurocognitive assessments).

RCT Comparing Chemotherapy with WBRT vs. Chemotherapy Alone (N = 1)

The G-PCNSL-SG-1 trial reported OS defined as time between randomization and death or the date when “last seen alive”. The publication of Thiel et al. reported no significant differences regarding the primary endpoint OS, but non-inferiority was not proven (non-inferiority margin of 0.9) when WBRT was omitted from chemotherapy. A subgroup analysis for patients with an age cut-off of 60 years (irrespective of intervention group) showed overall mild toxicity without statistically significant differences between patients > 60 years and ≤60 years of age. The authors concluded that HD-MTX chemotherapy is a safe treatment option across different age groups in newly diagnosed PCNSL patients with adequate renal function [49].

Roth et al. assessed the outcomes of older patients (≥70 years) treated within the G-PCNSL-SG-1 trial irrespective of their allocation to the two treatment arms. Overall, older patients (≥70 years) showed significantly lower remission rates and inferior OS and PFS rates than younger patients (<70 years). When analyzing the response to HD-MTX-based chemotherapy, PFS in patients with CR was lower in older patients when compared to younger patients (mean PFS: 16.1 months in older patients (≥70 years) vs. 35.0 months in younger patients (<70 years)) [24]. Toxicity was age-independent except for a higher rate of grade 3 and 4 leukopenia in older patients (≥70 years).

RCTs Comparing Chemotherapy with WBRT vs. WBRT Alone (N = 1)

Mead et al. reported survival rates measured between randomization and date of death or the date “last seen alive” as primary outcome. After an earlier study closure due to poor recruitment, no statistically significant differences regarding OS were observed between the two treatment groups. On univariate log-rank analysis and multivariate Cox analysis, patient age and neurologic PS were of prognostic significance for survival irrespective of the two treatment groups. Older patients (≥60 years) with a bad pre-WBRT neurologic status had an inferior two-year OS rate of 18% (range 0–40%; 95% CI not provided) compared to younger patients (<60 years) with a good pre-WBRT neurologic status (2–year OS rate 59%, range 37–80%; 95% CI not provided) [50].

RCTs Evaluating HCT-ASCT (N = 2, Results Not Applicable for Elderly or Pending)

The IELSG32 phase II RCT reported two-year PFS as primary outcome: with a two-year PFS of 80% (95% CI 70–90) for 59 patients with consolidating WBRT and 69% (95% CI 59–79) for 59 patients with consolidating HCT-ASCT; no significant differences were observed between the treatment groups. Importantly, exploratory analyses showed similar survival outcomes between different age-groups: 18–59 years, 60–64 years and 65–70 (ECOG PS ≤ 2) years [32]. Nevertheless, infective complications were observed more frequently in older patients (>60 years) [51]. The ongoing MATRix/IELSG43 trial defined PFS as primary outcome. Further outcomes are CR rate, duration of response, OS, QoL, toxicity and neurotoxicity defined according to Mini-Mental State Examination, QoL and neuro-psychological battery. As follow-up is still ongoing, results are pending.

3.2. Prospective Non-Randomized Studies

3.2.1. Key Characteristics of Prospective Non-Randomized Studies

Study key data: The key characteristics of the 26 prospective studies (25 completed, 1 ongoing) are displayed in Table 3. Two of these studies reported a control group. The remaining studies were single arm studies. The studies were published between 1992 and 2020. Only eight out of 26 studies were specifically designed for elderly patients with an age cut-off of 60 years or older [31,55,56,57,58,59,60,61]. The remaining studies included patients with a wider age range and also provided individual patient data or subgroup data for elderly patients. Nineteen studies included patients without providing an upper age limit.

Definition of patient population: While 22 studies investigated treatment in newly diagnosed PCNSL patients, four studies included patients with refractory or relapsed disease [62,63,64,65]. Adequate renal function and heterogeneous ECOG PS were frequently applied inclusion criteria for studies with HD-MTX treatment. The MARiTA pilot study (which investigated age-adapted HCT-ASCT treatment) only included patients with an ECOG PS ≤ 2 and a Cumulative Rating Illness Score Geriatrics (CIRS-G) of ≤6 (only considering symptoms not related to PCNSL) [60]. In the ongoing phase II MARTA study (which is also investigating HCT-ASCT) patients with an ECOG PS ≤ 2 are eligible [31].

Treatment protocols: Most studies focused on newly diagnosed PCNSL patients used first-line treatment protocols consisting of combined radio-chemo(immuno)therapy (8 studies) or chemo(immuno)therapy alone (14 studies). For induction treatment of newly diagnosed elderly PCNSL patients HD-MTX-based chemotherapy was applied in almost all studies (20 studies). Of note, the phase II PRIMAIN study has been the largest prospective study specifically designed for elderly PCNSL patients. This study established the combination of rituximab, HD-MTX and procarbazine as a promising treatment regimen in elderly patients [57]. Age-adapted HCT-ASCT as intensive consolidation treatment for elderly patients was investigated in one pilot study including 14 patients [60]. Furthermore, a study protocol of an ongoing phase II study investigating HCT-ASCT was identified. This study only recently completed recruitment of 51 participants [31].

In the relapse/refractory patient setting, novel agents like ibrutinib and temsirolimus as well as the alkylating agent temozolomide were investigated.

3.2.2. Overall Findings of Prospective Non-Randomized Studies

Efficacy outcomes such as PFS, OS and remission rates and safety outcomes (particularly toxicity parameters) were commonly assessed. However, neurotoxicity assessment data in elderly patients were only reported in four studies investigating combination chemotherapy protocols with [66] or without radiotherapy [67], with intraventricular chemotherapy [68] and with consolidating HCT-ASCT [60]. In the study by Bessel et al. (using systemic chemotherapy combined with WBRT), severe (neuro-)toxicity was increased in older PCNSL patients (≥60 years) compared to younger patients (<60 years). Only 1/12 (8%) of younger patients (<60 years at diagnosis) showed mild cognitive dysfunction after standard dose WBRT whereas 6/10 (60%) of older patients ≥ 60 years developed dementia [69]. Overall, survival outcomes in elderly PCNSL patients were poor with encouraging but limited data for treatment protocols comprising maintenance treatment [56,59,70] or HCT-ASCT [60]. With one- and two-year PFS rates of 46.3% (95% CI 38.8–55.8) and 37.3% (28.0–46.6) and respective OS rates after one- and two-years of 56.7% (95% CI 47.2–66.1) and 47% (95% CI 37.3–56.7), the PRIMAIN regimen showed positive results but was also associated with significant toxicities. The treatment related mortality rate was 8.4% whereas 81.3% of the patients experienced grade 3 or 4 toxicities. The most frequent reported toxicities were leukopenia (55.1%), infections (35.5%), and anemia (32.7%) [57]. With two-year PFS and OS rates of 92.9% (95% CI 80.3–100) and 92.3% (95% CI 78.9–100), prospective data of the bicentric MARiTA study show promising results of the proposed age-adapted HCT-ASCT approach in this population of elderly PCNSL patients. No treatment related mortality was observed and infective complications were similar to the ones reported in the PRIMAIN study [60]. The subsequent phase II MARTA trial recently completed recruitment of 51 patients but follow-up is still ongoing and efficacy and toxicity outcomes are pending [31].

3.3. Retrospective Studies

3.3.1. Key Characteristics of Retrospective Studies

Study key data: The key characteristics of the 24 identified retrospective studies are displayed in Table S1. The studies were published between 1994 and 2020. Nearly half of the studies (N = 13) focused on elderly PCNSL patients. The remaining studies included a wider age range (from 12 years with no upper age limit). These studies, however, provided individual patient data or subgroup analyses for elderly patients. The study by Welch et al. reported outcomes of the oldest PCNSL patient population (≥80) [80].

Definition of patient population: Patient populations of the reported retrospective studies are heterogeneous. Only four studies included more than 100 elderly PCNSL patients (range 133–717 patients) [17,81,82,83]. The remaining studies included between 11 and 90 participants. Treatment was either based on physician’s choice and/or or performance status and age. Median age of PCNSL patients (≥65 years) undergoing HCT-ASCT was 68.5 years with a KPS of 80% [30].

Treatment protocols: Overall, first-line treatment protocols mainly consisted of MTX-based chemotherapy protocols. The largest series by Houillier et al. reported data of 717 PCNSL patients > 60 years being treated with various chemotherapy protocols. Interestingly, HD-MTX was administered even in 84% of the oldest patients aged over 80 years. However, less than half of those patients received HD-MTX doses ≥ 3 g/m2. Furthermore, only 2% of those patients aged > 60 years received HCT-ASCT consolidation [17]. Detailed information regarding consolidation treatment with HCT- ASCT in elderly patients was reported in only two studies [30,84]. Kassam et al. reported data for 70 patients undergoing HCT-ASCT in first response after HD-MTX containing induction treatment [84]. Schorb et al. reported data of overall 52 patients who underwent thiotepa-based HCT-ASCT with 28.8% of them receiving HCT-ASCT as first-line treatment and 71.2% of them as second or subsequent line [30].

3.3.2. Key Outcomes of Retrospective Studies Investigating HCT-ASCT

Reported outcomes for elderly PCNSL patients undergoing HCT-ASCT as first-line consolidation treatment are encouraging: A European retrospective study authored by Schorb et al. investigating HCT-ASCT in elderly PCNSL patients (≥65 years) reported an overall response rate of 86.5% and a two-year PFS rate of 62% (95% CI 48.4–96) (N = 15) [30]. Another retrospective multicenter study from the UK reported by Kassam et al. investigated HCT-ASCT as first-line treatment. The study included 70 patients (age range 27–74) and concluded that age (≥5 years) was not a risk factor for treatment-related death. All 4 (from 23) patients who died in this age group ≥ 65 years) received a total thiotepa dose of 20 mg/kg. Other outcomes for elderly patients were not reported in this study [84].

4. Discussion

In total we identified five completed [32,42,43,45,49,50] and one ongoing RCT [29], 26 prospective studies (two with control [67,69], 24 single arm studies [31,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,68,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79] and 24 retrospective studies (with or without control) [17,30,37,45,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99] investigating different approaches in immunocompetent PCNSL patients. However, only one completed prospective pilot trial [60], one ongoing prospective phase II trial [31], and two retrospective studies [30,84] specifically investigated intensified consolidation treatment with HCT-ASCT in elderly PCNSL patients. Not only with regard to this intensive therapy regime, but in general, the data on therapy for the elderly patients with PCNSL is very limited as elderly PCNSL patients are under-represented in clinical trials. Comorbidities, poor baseline PS and potential drug toxicity are considered major issues in treating patients within this age group [23]. Elderly PCNSL patients frequently fail to receive optimal treatment owing to the lack of well-established treatment standards and geriatric assessment tools to guide treatment intensification. Recent treatment recommendations suggest that MTX should be aimed at the maximal tolerated dose for elderly patients and that dose reductions are likely to impact treatment outcomes [23]. Thus, the identification of optimal therapy and adequate dose intensity are very important factors in treating elderly PCNSL patients.

High-dose chemotherapy followed by ASCT is known to be a highly effective treatment strategy for non-Hodgkin lymphomas [100]. The rationale for HCT-ACST in PCNSL is the delivery of blood-brain-barrier penetrating agents in several-fold higher concentrations, which cannot be achieved with conventionally dosed therapy [78,101]. During the past years, 2 RCTs [32,33] have established HCT-ASCT in PCNSL patients up to the age of 65 to 70 years as a widely used treatment approach in younger PCNSL patients [30,60,102]. The RCT by Ferreri et al. included patients up to the age of 65 years or between 65 and 70 years in case of a good PS (ECOG PS ≤ 2) and provided subgroup analyses for those 2 age groups. Exploratory analyses showed that outcome for elderly patients (65–70 years with an ECOG PS of ≤2) had similar survival outcomes as younger patients [32].

Nevertheless, infective complications were observed more frequently in patients aged older than 60 years [51], underlying the important role of supportive care (including antiinfective prophylaxis) in this vulnerable subgroup of patients. This will be addressed in our randomized phase III trial by the addition of pre-specified anti-infective prophylaxis measures and a pre-phase treatment with rituximab and HD-MTX with the aim to reduce infectious complications. The ongoing randomized phase III MATRix/IELSG43 trial has recently completed recruitment; results will further define the role of HCT-ASCT in PCNSL patients up to the age of 70 years.

The PRECIS trial by Houillier et al. is another phase II trial that compared WBRT to HCT-ASCT as consolidative strategies in PCNSL. The trial, however, included younger patients up to age 60 only (therefore it is not included in the current scoping review). Patients received rituximab, etoposide, carmustine, prednisone and cytarabine as induction therapy. Those with response received either WBRT or HCT-ASCT. Based on this results and various single arm studies [34,35,36,38] HCT-ASCT has been established as a widely used treatment approach in PCNSL patients up to the age of 65 to 70 years. These findings are supported by the results of a systemic review and meta-analysis including 43 studies and reporting outcome data of mainly thiotepa-based HCT-ASCT as consolidating or salvage treatment in PCNSL patients with a median age range between 42 and 68.5 years [102]. Alnahhas et al. reported an overall response rate of 94% after consolidative HCT-ASCT with respective two-year OS and PFS rates of 86% and 70%.

In contrast to the improvement of outcomes in younger patients, treatment strategies for elderly PCNSL patients are slow to progress and intensified treatment protocols are applied only in a small subgroup of patients.

Similar to that of those with systemic lymphoma entities, geriatric assessment could be an important tool to guide treatment intensity in elderly PCNSL patients [103]. However, to date, supporting evidence is scarce and there is only one retrospective study that investigated the impact of comorbidities on treatment feasibility and outcome measures in elderly PCNSL patients [85]. Farhi et al. investigated three comorbidity scores, the CCI, the CIRS-G and the G8. The authors found an association between a high CIRS-G score and shorter PFS and OS in univariate analysis, but these findings could not be confirmed in multivariate analysis [85]. The evaluation of applicability and utility of geriatric assessment tools should clearly be incorporated in future prospective trials, and will be also part of our planned randomized phase III PRIMA-CNS trial.

Interestingly, despite the rarity of the disease and the major therapeutic challenges, recruitment was successfully completed in all prospective studies specifically designed for elderly patients. Only one study with an age-adjusted chemotherapy approach for patients aged 31–75 years was terminated prematurely due to a high treatment related mortality rate of 16.7% [75].

The only randomized trial specifically designed for elderly PCNSL patients reported an improved efficacy without significant differences in toxicity in the more intensive chemotherapy arm comprising MTX, procarbazine, vincristine and AraC when compared to MTX and temozolomide alone [43] suggesting that this treatment approach in eligible elderly PCNSL patients may be promising.

In summary, despite encouraging data regarding the use of intensive therapy strategies even in elderly PCNSL patients, none of the reported randomized trials in PCNSL investigated an intensive treatment approach comprising HCT-ASCT in elderly PCNSL patients. Importantly, searching in different trial registers also did not reveal any ongoing randomized trial investigating this specific research question. Thus, there is an urgent need to perform a RCT addressing this treatment approach to provide elderly PCNSL with the best option currently available.

5. Conclusions

The results of our literature review reveal a shortage of studies that evaluate intensified chemotherapy protocols in elderly PCNSL patients. The mapping of the published literature revealed a heterogeneous study pool with regard to sample sizes, treatment protocols and toxicity data. The limitations and heterogeneity of the existing body of evidence reduce its utility for informing clinical treatment choices. Notably, clinical data regarding HCT-ASCT treatment in the elderly is scarce. Although it has been shown that HCT-ASCT is probably effective, this treatment approach has never been investigated within a well conducted RCT including a wide range of elderly patients. A thoroughly planned RCT comparing HCT-ASCT with the current treatment standard (of conventional combination chemoimmunotherapy) is, therefore, of great clinical importance to provide older PCNSL patients with the most effective treatment option.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cancers13174268/s1, Table S1: Characteristics of retrospective studies, Table S2: Systematic literature search.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S. and C.S.; Methodology, B.N., K.G. and C.S.; Validation, E.S. and C.S.; Formal Analysis, B.N. and C.S.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, E.S. and C.S.; Writing—Review & Editing, L.K.I., G.I. (Gerald Illerhaus), G.I. (Gabriele Ihorst), B.N., J.J.M., K.G. and C.S.; Supervision, C.S.; Funding Acquisition, E.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a research grant (grand number 01KD1904) “Nationale Dekade gegen Krebs” provided to Elisabeth Schorb by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). Additionally, Elisabeth Schorb’s position was partially funded by the Berta-Ottenstein-Programme for Advanced Clinician Scientists, Faculty of Medicine, University of Freiburg.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or Supplementary Material. The primary data presented in this systematic review are available in the primary studies cited in the reference list.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jonathan R. Isbell for proofreading.

Conflicts of Interest

E.S. and G.I. (Gerald Illerhaus) receive speakers’ honoraries and research funding from Riemser Pharma GmbH and research funding from Roche Pharma AG and AbbVie. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Shiels, M.S.; Pfeiffer, R.M.; Besson, C.; Clarke, C.A.; Morton, L.M.; Nogueira, L.; Pawlish, K.; Yanik, E.L.; Suneja, G.; Engels, E.A. Trends in primary central nervous system lymphoma incidence and survival in the U.S. Br. J. Haematol. 2016, 174, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Gittleman, H.; Truitt, G.; Boscia, A.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. Cbtrus statistical report: Primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2011–2015. Neuro Oncol. 2018, 20, iv1–iv86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendez, J.S.; Ostrom, Q.T.; Gittleman, H.; Kruchko, C.; DeAngelis, L.M.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S.; Grommes, C. The elderly left behind-changes in survival trends of primary central nervous system lymphoma over the past 4 decades. Neuro Oncol. 2018, 20, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swerdlow, S.H.; Campo, E.; Pileri, S.A.; Harris, N.L.; Stein, H.; Siebert, R.; Advani, R.; Ghielmini, M.; Salles, G.A.; Zelenetz, A.D.; et al. The 2016 revision of the world health organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood 2016, 127, 2375–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapuy, B.; Roemer, M.G.; Stewart, C.; Tan, Y.; Abo, R.P.; Zhang, L.; Dunford, A.J.; Meredith, D.M.; Thorner, A.R.; Jordanova, E.S.; et al. Targetable genetic features of primary testicular and primary central nervous system lymphomas. Blood 2016, 127, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesinos-Rongen, M.; Purschke, F.; Kuppers, R.; Deckert, M. Immunoglobulin repertoire of primary lymphomas of the central nervous system. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2014, 73, 1116–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhouachi, N.; Xochelli, A.; Boudjoghra, M.; Lesty, C.; Cassoux, N.; Fardeau, C.; Tran, T.H.C.; Choquet, S.; Sarker, B.; Houillier, C.; et al. Primary vitreoretinal lymphomas display a remarkably restricted immunoglobulin gene repertoire. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 1357–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri-Broet, S.; Criniere, E.; Broet, P.; Delwail, V.; Mokhtari, K.; Moreau, A.; Kujas, M.; Raphael, M.; Iraqi, W.; Sautes-Fridman, C.; et al. A uniform activated B-cell-like immunophenotype might explain the poor prognosis of primary central nervous system lymphomas: Analysis of 83 cases. Blood 2006, 107, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesinos-Rongen, M.; Brunn, A.; Bentink, S.; Basso, K.; Lim, W.K.; Klapper, W.; Schaller, C.; Reifenberger, G.; Rubenstein, J.; Wiestler, O.D.; et al. Gene expression profiling suggests primary central nervous system lymphomas to be derived from a late germinal center B cell. Leukemia 2008, 22, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattab, E.M.; Martin, S.E.; Al-Khatib, S.M.; Kupsky, W.J.; Vance, G.H.; Stohler, R.A.; Czader, M.; Al-Abbadi, M.A. Most primary central nervous system diffuse large B-cell lymphomas occurring in immunocompetent individuals belong to the nongerminal center subtype: A retrospective analysis of 31 cases. Mod. Pathol. 2010, 23, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahale, P.; Shiels, M.S.; Lynch, C.F.; Engels, E.A. Incidence and outcomes of primary central nervous system lymphoma in solid organ transplant recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 2018, 18, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, N.K.; Nolan, A.; Omuro, A.; Reid, E.G.; Wang, C.C.; Mannis, G.; Jaglal, M.; Chavez, J.C.; Rubinstein, P.G.; Griffin, A.; et al. Long-term survival in aids-related primary central nervous system lymphoma. Neuro Oncol. 2017, 19, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, M.K.; Hoang, T.; Law, S.C.; Brosda, S.; O’Rourke, K.; Tobin, J.W.D.; Vari, F.; Murigneux, V.; Fink, L.; Gunawardana, J.; et al. Ebv-associated primary CNS lymphoma occurring after immunosuppression is a distinct immunobiological entity. Blood 2021, 137, 1468–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponzoni, M.; Berger, F.; Chassagne-Clement, C.; Tinguely, M.; Jouvet, A.; Ferreri, A.J.; Dell’Oro, S.; Terreni, M.R.; Doglioni, C.; Weis, J.; et al. Reactive perivascular t-cell infiltrate predicts survival in primary central nervous system B-cell lymphomas. Br. J. Haematol. 2007, 138, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aki, H.; Uzunaslan, D.; Saygin, C.; Batur, S.; Tuzuner, N.; Kafadar, A.; Ongoren, S.; Oz, B. Primary central nervous system lymphoma in immunocompetent individuals: A single center experience. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2013, 6, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Hu, L.B.; Henning, T.D.; Ravarani, E.M.; Zou, L.G.; Feng, X.Y.; Wang, W.X.; Wen, L. Mri findings of primary CNS lymphoma in 26 immunocompetent patients. Korean J. Radiol. 2010, 11, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houillier, C.; Soussain, C.; Ghesquieres, H.; Soubeyran, P.; Chinot, O.; Taillandier, L.; Lamy, T.; Choquet, S.; Ahle, G.; Damaj, G.; et al. Management and outcome of primary CNS lymphoma in the modern era: An loc network study. Neurology 2020, 94, e1027–e1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrey, L.E.; Batchelor, T.T.; Ferreri, A.J.; Gospodarowicz, M.; Pulczynski, E.J.; Zucca, E.; Smith, J.R.; Korfel, A.; Soussain, C.; DeAngelis, L.M.; et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize baseline evaluation and response criteria for primary CNS lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 5034–5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerbauy, M.N.; Moraes, F.Y.; Lok, B.H.; Ma, J.; Kerbauy, L.N.; Spratt, D.E.; Santos, F.P.; Perini, G.F.; Berlin, A.; Chung, C.; et al. Challenges and opportunities in primary CNS lymphoma: A systematic review. Radiother. Oncol. 2017, 122, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreri, A.J.; Blay, J.Y.; Reni, M.; Pasini, F.; Spina, M.; Ambrosetti, A.; Calderoni, A.; Rossi, A.; Vavassori, V.; Conconi, A.; et al. Prognostic scoring system for primary CNS lymphomas: The international extranodal lymphoma study group experience. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrey, L.E.; Ben-Porat, L.; Panageas, K.S.; Yahalom, J.; Berkey, B.; Curran, W.; Schultz, C.; Leibel, S.; Nelson, D.; Mehta, M.; et al. Primary central nervous system lymphoma: The memorial sloan-kettering cancer center prognostic model. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 5711–5715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filley, C.M.; Kleinschmidt-DeMasters, B.K. Toxic leukoencephalopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Calle, N.; Isbell, L.K.; Cwynarski, K.; Schorb, E. Treatment of elderly patients with primary CNS lymphoma. Ann. Lymphoma 2021, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, P.; Martus, P.; Kiewe, P.; Mohle, R.; Klasen, H.; Rauch, M.; Roth, A.; Kaun, S.; Thiel, E.; Korfel, A.; et al. Outcome of elderly patients with primary CNS lymphoma in the g-PCNSL-sg-1 trial. Neurology 2012, 79, 890–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegal, T.; Bairey, O. Primary CNS lymphoma in the elderly: The challenge. Acta Haematol. 2019, 141, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorb, E.; Fox, C.P.; Kasenda, B.; Linton, K.; Martinez-Calle, N.; Calimeri, T.; Ninkovic, S.; Eyre, T.A.; Cummin, T.; Smith, J.; et al. Induction therapy with the matrix regimen in patients with newly diagnosed primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the central nervous system—An international study of feasibility and efficacy in routine clinical practice. Br. J. Haematol. 2020, 189, 879–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, P.; Hoang-Xuan, K. Challenges in the treatment of elderly patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2014, 27, 697–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivier, G.; Clavert, A.; Lacotte-Thierry, L.; Gardembas, M.; Escoffre-Barbe, M.; Brion, A.; Cumin, I.; Legouffe, E.; Solal-Celigny, P.; Chabin, M.; et al. A phase 1 dose escalation study of idarubicin combined with methotrexate, vindesine, and prednisolone for untreated elderly patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma. The GOELAMS LCP 99 trial. Am. J. Hematol. 2014, 89, 1024–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorb, E.; Finke, J.; Ferreri, A.J.; Ihorst, G.; Mikesch, K.; Kasenda, B.; Fritsch, K.; Fricker, H.; Burger, E.; Grishina, O.; et al. High-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant compared with conventional chemotherapy for consolidation in newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma—A randomized phase iii trial (matrix). BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorb, E.; Fox, C.P.; Fritsch, K.; Isbell, L.; Neubauer, A.; Tzalavras, A.; Witherall, R.; Choquet, S.; Kuittinen, O.; De-Silva, D.; et al. High-dose thiotepa-based chemotherapy with autologous stem cell support in elderly patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma: A european retrospective study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017, 52, 1113–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorb, E.; Finke, J.; Ihorst, G.; Kasenda, B.; Fricker, H.; Illerhaus, G. Age-adjusted high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant in elderly and fit primary CNS lymphoma patients. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreri, A.J.M.; Cwynarski, K.; Pulczynski, E.; Fox, C.P.; Schorb, E.; La Rosee, P.; Binder, M.; Fabbri, A.; Torri, V.; Minacapelli, E.; et al. Whole-brain radiotherapy or autologous stem-cell transplantation as consolidation strategies after high-dose methotrexate-based chemoimmunotherapy in patients with primary CNS lymphoma: Results of the second randomisation of the international extranodal lymphoma study group-32 phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2017, 4, e510–e523. [Google Scholar]

- Houillier, C.; Taillandier, L.; Dureau, S.; Lamy, T.; Laadhari, M.; Chinot, O.; Molucon-Chabrot, C.; Soubeyran, P.; Gressin, R.; Choquet, S.; et al. Radiotherapy or autologous stem-cell transplantation for primary CNS lymphoma in patients 60 years of age and younger: Results of the intergroup anocef-goelams randomized phase ii precis study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illerhaus, G.; Kasenda, B.; Ihorst, G.; Egerer, G.; Lamprecht, M.; Keller, U.; Wolf, H.H.; Hirt, C.; Stilgenbauer, S.; Binder, M.; et al. High-dose chemotherapy with autologous haemopoietic stem cell transplantation for newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma: A prospective, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2016, 3, e388–e397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illerhaus, G.; Marks, R.; Ihorst, G.; Guttenberger, R.; Ostertag, C.; Derigs, G.; Frickhofen, N.; Feuerhake, F.; Volk, B.; Finke, J. High-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem-cell transplantation and hyperfractionated radiotherapy as first-line treatment of primary CNS lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 3865–3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illerhaus, G.; Muller, F.; Feuerhake, F.; Schafer, A.O.; Ostertag, C.; Finke, J. High-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation without consolidating radiotherapy as first-line treatment for primary lymphoma of the central nervous system. Haematologica 2008, 93, 147–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasenda, B.; Rehberg, M.; Thurmann, P.; Franzem, M.; Veelken, H.; Fritsch, K.; Schorb, E.; Finke, J.; Lebiedz, D.; Illerhaus, G. The prognostic value of serum methotrexate area under curve in elderly primary CNS lymphoma patients. Ann. Hematol. 2012, 91, 1257–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omuro, A.; Correa, D.D.; DeAngelis, L.M.; Moskowitz, C.H.; Matasar, M.J.; Kaley, T.J.; Gavrilovic, I.T.; Nolan, C.; Pentsova, E.; Grommes, C.C.; et al. R-MPV followed by high-dose chemotherapy with tbc and autologous stem-cell transplant for newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma. Blood 2015, 125, 1403–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorb, E.; Kasenda, B.; Atta, J.; Kaun, S.; Morgner, A.; Hess, G.; Elter, T.; von Bubnoff, N.; Dreyling, M.; Ringhoffer, M.; et al. Prognosis of patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma after high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation. Haematologica 2013, 98, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.; Colquhoun, H.; Kastner, M.; Levac, D.; Ng, C.; Sharpe, J.P.; Wilson, K.; et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, M.; McGowan, J.; Cogo, E.; Grimshaw, J.; Moher, D.; Lefebvre, C. An evidence-based practice guideline for the peer review of electronic search strategies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The prisma 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omuro, A.; Chinot, O.; Taillandier, L.; Ghesquieres, H.; Soussain, C.; Delwail, V.; Lamy, T.; Gressin, R.; Choquet, S.; Soubeyran, P.; et al. Methotrexate and temozolomide versus methotrexate, procarbazine, vincristine, and cytarabine for primary CNS lymphoma in an elderly population: An intergroup anocef-goelams randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2015, 2, e251–e259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromberg, J.E.C.; Issa, S.; Bakunina, K.; Minnema, M.C.; Seute, T.; Durian, M.; Cull, G.; Schouten, H.C.; Stevens, W.B.C.; Zijlstra, J.M.; et al. Rituximab in patients with primary CNS lymphoma (HOVON 105/ALLG NHL 24): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 intergroup study. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omuro, A.M.; Taillandier, L.; Chinot, O.; Carnin, C.; Barrie, M.; Hoang-Xuan, K. Temozolomide and methotrexate for primary central nervous system lymphoma in the elderly. J. Neurooncol. 2007, 85, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, E.; Korfel, A.; Martus, P.; Kanz, L.; Griesinger, F.; Rauch, M.; Roth, A.; Hertenstein, B.; von Toll, T.; Hundsberger, T.; et al. High-dose methotrexate with or without whole brain radiotherapy for primary CNS lymphoma (g-PCNSL-sg-1): A phase 3, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11, 1036–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korfel, A.; Thiel, E.; Martus, P.; Mohle, R.; Griesinger, F.; Rauch, M.; Roth, A.; Hertenstein, B.; Fischer, T.; Hundsberger, T.; et al. Randomized phase iii study of whole-brain radiotherapy for primary CNS lymphoma. Neurology 2015, 84, 1242–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrlinger, U.; Schafer, N.; Fimmers, R.; Griesinger, F.; Rauch, M.; Kirchen, H.; Roth, P.; Glas, M.; Bamberg, M.; Martus, P.; et al. Early whole brain radiotherapy in primary CNS lymphoma: Negative impact on quality of life in the randomized g-PCNSL-sg1 trial. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 143, 1815–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahnke, K.; Korfel, A.; Martus, P.; Weller, M.; Herrlinger, U.; Schmittel, A.; Fischer, L.; Thiel, E.; German Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma Study Group. High-dose methotrexate toxicity in elderly patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma. Ann. Oncol. 2005, 16, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mead, G.M.; Bleehen, N.M.; Gregor, A.; Bullimore, J.; Shirley, D.; Rampling, R.P.; Trevor, J.; Glaser, M.G.; Lantos, P.; Ironside, J.W.; et al. A medical research council randomized trial in patients with primary cerebral non-hodgkin lymphoma: Cerebral radiotherapy with and without cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone chemotherapy. Cancer 2000, 89, 1359–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreri, A.J.; Cwynarski, K.; Pulczynski, E.; Ponzoni, M.; Deckert, M.; Politi, L.S.; Torri, V.; Fox, C.P.; Rosee, P.L.; Schorb, E.; et al. Chemoimmunotherapy with methotrexate, cytarabine, thiotepa, and rituximab (matrix regimen) in patients with primary CNS lymphoma: Results of the first randomisation of the international extranodal lymphoma study group-32 (ielsg32) phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2016, 3, e217–e227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaronson, N.K.; Ahmedzai, S.; Bergman, B.; Bullinger, M.; Cull, A.; Duez, N.J.; Filiberti, A.; Flechtner, H.; Fleishman, S.B.; de Haes, J.C.; et al. The european organization for research and treatment of cancer qlq-c30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1993, 85, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheson, B.D.; Pfistner, B.; Juweid, M.E.; Gascoyne, R.D.; Specht, L.; Horning, S.J.; Coiffier, B.; Fisher, R.I.; Hagenbeek, A.; Zucca, E.; et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correa, D.D.; Maron, L.; Harder, H.; Klein, M.; Armstrong, C.L.; Calabrese, P.; Bromberg, J.E.; Abrey, L.E.; Batchelor, T.T.; Schiff, D. Cognitive functions in primary central nervous system lymphoma: Literature review and assessment guidelines. Ann. Oncol. 2007, 18, 1145–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.; Kim, J.; Ryu, H.J.; Roh, H.G.; Chung, H.W.; Koh, Y.C.; Lee, M.H.; Ko, Y.H.; Kim, S.Y. Pilot study of gamma-knife surgery-incorporated systemic chemotherapy omitting whole brain radiotherapy for the treatment of elderly primary central nervous system lymphoma patients with poor prognostic scores. Med. Oncol. 2014, 31, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, K.; Kasenda, B.; Hader, C.; Nikkhah, G.; Prinz, M.; Haug, V.; Haug, S.; Ihorst, G.; Finke, J.; Illerhaus, G. Immunochemotherapy with rituximab, methotrexate, procarbazine, and lomustine for primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL) in the elderly. Ann. Oncol. 2011, 22, 2080–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritsch, K.; Kasenda, B.; Schorb, E.; Hau, P.; Bloehdorn, J.; Mohle, R.; Low, S.; Binder, M.; Atta, J.; Keller, U.; et al. High-dose methotrexate-based immuno-chemotherapy for elderly primary CNS lymphoma patients (primain study). Leukemia 2017, 31, 846–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoang-Xuan, K.; Taillandier, L.; Chinot, O.; Soubeyran, P.; Bogdhan, U.; Hildebrand, J.; Frenay, M.; De Beule, N.; Delattre, J.Y.; Baron, B.; et al. Chemotherapy alone as initial treatment for primary CNS lymphoma in patients older than 60 years: A multicenter phase ii study (26952) of the european organization for research and treatment of cancer brain tumor group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 2726–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illerhaus, G.; Marks, R.; Muller, F.; Ihorst, G.; Feuerhake, F.; Deckert, M.; Ostertag, C.; Finke, J. High-dose methotrexate combined with procarbazine and CCNU for primary CNS lymphoma in the elderly: Results of a prospective pilot and phase ii study. Ann. Oncol. 2009, 20, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorb, E.; Kasenda, B.; Ihorst, G.; Scherer, F.; Wendler, J.; Isbell, L.; Fricker, H.; Finke, J.; Illerhaus, G. High-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant in elderly patients with primary CNS lymphoma: A pilot study. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 3378–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.J.; Gerstner, E.R.; Engler, D.A.; Mrugala, M.M.; Nugent, W.; Nierenberg, K.; Hochberg, F.H.; Betensky, R.A.; Batchelor, T.T. High-dose methotrexate for elderly patients with primary CNS lymphoma. Neuro Oncol. 2009, 11, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korfel, A.; Schlegel, U.; Herrlinger, U.; Dreyling, M.; Schmidt, C.; von Baumgarten, L.; Pezzutto, A.; Grobosch, T.; Kebir, S.; Thiel, E.; et al. Phase ii trial of temsirolimus for relapsed/refractory primary CNS lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 1757–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langner-Lemercier, S.; Houillier, C.; Soussain, C.; Ghesquieres, H.; Chinot, O.; Taillandier, L.; Soubeyran, P.; Lamy, T.; Morschhauser, F.; Benouaich-Amiel, A.; et al. Primary CNS lymphoma at first relapse/progression: Characteristics, management, and outcome of 256 patients from the french loc network. Neuro Oncol. 2016, 18, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soussain, C.; Choquet, S.; Blonski, M.; Leclercq, D.; Houillier, C.; Rezai, K.; Bijou, F.; Houot, R.; Boyle, E.; Gressin, R.; et al. Ibrutinib monotherapy for relapse or refractory primary CNS lymphoma and primary vitreoretinal lymphoma: Final analysis of the phase ii ’proof-of-concept’ iloc study by the lymphoma study association (lysa) and the french oculo-cerebral lymphoma (loc) network. Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 117, 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Reni, M.; Mason, W.; Zaja, F.; Perry, J.; Franceschi, E.; Bernardi, D.; Dell’Oro, S.; Stelitano, C.; Candela, M.; Abbadessa, A.; et al. Salvage chemotherapy with temozolomide in primary CNS lymphomas: Preliminary results of a phase ii trial. Eur. J. Cancer 2004, 40, 1682–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessell, E.M.; Graus, F.; Lopez-Guillermo, A.; Villa, S.; Verger, E.; Petit, J.; Holland, I.; Byrne, P. Chod/bvam regimen plus radiotherapy in patients with primary CNS non-hodgkin’s lymphoma. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2001, 50, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa, T.; Kurozumi, K.; Michiue, H.; Ishida, J.; Maeda, Y.; Kondo, E.; Kawasaki, A.; Date, I. Reduced neurotoxicity with combined treatment of high-dose methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone (m-chop) and deferred radiotherapy for primary central nervous system lymphoma. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2014, 127, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pels, H.; Schmidt-Wolf, I.G.; Glasmacher, A.; Schulz, H.; Engert, A.; Diehl, V.; Zellner, A.; Schackert, G.; Reichmann, H.; Kroschinsky, F.; et al. Primary central nervous system lymphoma: Results of a pilot and phase ii study of systemic and intraventricular chemotherapy with deferred radiotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 4489–4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessell, E.M.; Lopez-Guillermo, A.; Villa, S.; Verger, E.; Nomdedeu, B.; Petit, J.; Byrne, P.; Montserrat, E.; Graus, F. Importance of radiotherapy in the outcome of patients with primary CNS lymphoma: An analysis of the CHOD/BVAM regimen followed by two different radiotherapy treatments. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.F.; Martz, K.L.; Bonner, H.; Nelson, J.S.; Newall, J.; Kerman, H.D.; Thomson, J.W.; Murray, K.J. Non-hodgkin’s lymphoma of the brain: Can high dose, large volume radiation therapy improve survival? Report on a prospective trial by the radiation therapy oncology group (RTOG): RTOG 8315. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1992, 23, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, B.P.; O’Fallon, J.R.; Earle, J.D.; Colgan, J.P.; Brown, L.D.; Krigel, R.L. Primary central nervous system non-hodgkin’s lymphoma: Survival advantages with combined initial therapy? Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1995, 33, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, B.P.; Wang, C.H.; O’Fallon, J.R.; Colgan, J.D.; Earle, J.D.; Krigel, R.L.; Brown, L.D.; McGinnis, W.L. Primary central nervous system non-hodgkin’s lymphoma (PCNSL): Survival advantages with combined initial therapy? A final report of the north central cancer treatment group (NCCTG) study 86-72-52. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1999, 43, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibamoto, Y.; Sasai, K.; Oya, N.; Hiraoka, M. Systemic chemotherapy with vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin and prednisolone following radiotherapy for primary central nervous system lymphoma: A phase ii study. J. Neurooncol. 1999, 42, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghesquieres, H.; Ferlay, C.; Sebban, C.; Perol, D.; Bosly, A.; Casasnovas, O.; Reman, O.; Coiffier, B.; Tilly, H.; Morel, P.; et al. Long-term follow-up of an age-adapted c5r protocol followed by radiotherapy in 99 newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphomas: A prospective multicentric phase ii study of the groupe d’etude des lymphomes de l’adulte (GELA). Ann. Oncol. 2010, 21, 842–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldkuhl, C.; Ekman, T.; Wiklund, T.; Telhaug, R.; Nordic Lymphoma, G. Age-adjusted chemotherapy for primary central-nervous system lymphoma—A pilot study. Acta Oncol. 2002, 41, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juergens, A.; Pels, H.; Rogowski, S.; Fliessbach, K.; Glasmacher, A.; Engert, A.; Reiser, M.; Diehl, V.; Vogt-Schaden, M.; Egerer, G.; et al. Long-term survival with favorable cognitive outcome after chemotherapy in primary central nervous system lymphoma. Ann. Neurol. 2010, 67, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulczynski, E.J.; Kuittinen, O.; Erlanson, M.; Hagberg, H.; Fossa, A.; Eriksson, M.; Nordstrom, M.; Ostenstad, B.; Fluge, O.; Leppa, S.; et al. Successful change of treatment strategy in elderly patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma by de-escalating induction and introducing temozolomide maintenance: Results from a phase ii study by the nordic lymphoma group. Haematologica 2015, 100, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, J.L.; Hsi, E.D.; Johnson, J.L.; Jung, S.H.; Nakashima, M.O.; Grant, B.; Cheson, B.D.; Kaplan, L.D. Intensive chemotherapy and immunotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed primary CNS lymphoma: CALGB 50202 (alliance 50202). J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 3061–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, K.H.; Lee, E.H.; Kim, Y.Z. Factors influencing the response to high dose methotrexate-based vincristine and procarbazine combination chemotherapy for primary central nervous system lymphoma. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2011, 26, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, M.R.; Omuro, A.; Deangelis, L.M. Outcomes of the oldest patients with primary CNS lymphoma treated at memorial sloan-kettering cancer center. Neuro Oncol. 2012, 14, 1304–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Calle, N.; Poynton, E.; Alchawaf, A.; Kassam, S.; Horan, M.; Rafferty, M.; Kelsey, P.; Scott, G.; Culligan, D.J.; Buckley, H.; et al. Outcomes of older patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma treated in routine clinical practice in the UK: Methotrexate dose intensity correlates with response and survival. Br. J. Haematol. 2020, 190, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ney, D.E.; Reiner, A.S.; Panageas, K.S.; Brown, H.S.; DeAngelis, L.M.; Abrey, L.E. Characteristics and outcomes of elderly patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma: The memorial sloan-kettering cancer center experience. Cancer 2010, 116, 4605–4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayakawa, T.; Takakura, K.; Abe, H.; Yoshimoto, T.; Tanaka, R.; Sugita, K.; Kikuchi, H.; Uozumi, T.; Hori, T.; Fukui, H.; et al. Primary central nervous system lymphoma in japan—A retrospective, co-operative study by CNS-lymphoma study group in Japan. J. Neurooncol. 1994, 19, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassam, S.; Chernucha, E.; O’Neill, A.; Hemmaway, C.; Cummins, T.; Montoto, S.; Lennard, A.; Adams, G.; Linton, K.; McKay, P.; et al. High-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation for primary central nervous system lymphoma: A multi-centre retrospective analysis from the United Kingdom. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017, 52, 1268–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhi, J.; Laribi, K.; Orvain, C.; Hamel, J.F.; Mercier, M.; Sutra Del Galy, A.; Clavert, A.; Rousselet, M.C.; Tanguy-Schmidt, A.; Hunault-Berger, M.; et al. Impact of front line relative dose intensity for methotrexate and comorbidities in immunocompetent elderly patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma. Ann. Hematol. 2018, 97, 2391–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Ji, Y.; Ouyang, M.; Zhu, T.; Zhou, D. Efficacy and safety of hd-mtx based systemic chemotherapy regimens: Retrospective study of induction therapy for primary central nervous system lymphoma in Chinese. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakasu, Y.; Mitsuya, K.; Hayashi, N.; Okamura, I.; Mori, K.; Enami, T.; Tatara, R.; Nakasu, S.; Ikeda, T. Response-adapted treatment with upfront high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem-cell transplantation rescue or consolidation phase high-dose methotrexate for primary central nervous system lymphoma: A long-term mono-center study. Springerplus 2016, 5, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuurmans, M.; Bromberg, J.E.; Doorduijn, J.; Poortmans, P.; Taphoorn, M.J.; Seute, T.; Enting, R.; van Imhoff, G.; van Norden, Y.; van den Bent, M.J. Primary central nervous system lymphoma in the elderly: A multicentre retrospective analysis. Br. J. Haematol. 2010, 151, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, H.; Dahiya, S.; Murphy, E.S.; Chao, S.T.; Suh, J.H.; Stevens, G.H.; Peereboom, D.M.; Ahluwalia, M.S. Primary central nervous system lymphoma in the elderly: The cleveland clinic experience. Anticancer Res. 2013, 33, 3251–3258. [Google Scholar]

- Fliessbach, K.; Urbach, H.; Helmstaedter, C.; Pels, H.; Glasmacher, A.; Kraus, J.A.; Klockgether, T.; Schmidt-Wolf, I.; Schlegel, U. Cognitive performance and magnetic resonance imaging findings after high-dose systemic and intraventricular chemotherapy for primary central nervous system lymphoma. Arch. Neurol. 2003, 60, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaviani, P.; Simonetti, G.; Innocenti, A.; Lamperti, E.; Botturi, A.; Silvani, A. Safety and efficacy of primary central nervous system lymphoma treatment in elderly population. Neurol. Sci. 2016, 37, 131–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, G.; Arumugaswamy, A.; Leung, T.; Chan, K.L.; Abikhair, M.; Tam, C.; Bajel, A.; Cher, L.; Grigg, A.; Ritchie, D.; et al. Rituximab is associated with improved survival for aggressive B cell CNS lymphoma. Neuro Oncol. 2013, 15, 1068–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Houillier, C.; Ghesquieres, H.; Chabrot, C.; Soussain, C.; Ahle, G.; Choquet, S.; Nicolas-Virelizier, E.; Bay, J.O.; Vargaftig, J.; Gaultier, C.; et al. Rituximab, methotrexate, procarbazine, vincristine and intensified cytarabine consolidation for primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) in the elderly: A loc network study. J. Neurooncol. 2017, 133, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collignon, A.; Houillier, C.; Ahle, G.; Chinot, O.; Choquet, S.; Schmitt, A.; Agape, P.; Soussain, C.; Hoang-Xuan, K.; Tabouret, E. (r)-gemox chemotherapy for unfit patients with refractory or recurrent primary central nervous system lymphoma: A loc study. Ann. Hematol. 2019, 98, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Okoshi, Y.; Kurita, N.; Seki, M.; Yokoyama, Y.; Maie, K.; Hasegawa, Y.; Chiba, S. Prognosis factors in japanese elderly patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma treated with a nonradiation, intermediate-dose methotrexate-containing regimen. Oncol. Res. Treat. 2014, 37, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makino, K.; Nakamura, H.; Hide, T.; Kuroda, J.; Yano, S.; Kuratsu, J. Prognostic impact of completion of initial high-dose methotrexate therapy on primary central nervous system lymphoma: A single institution experience. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 20, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madle, M.; Kramer, I.; Lehners, N.; Schwarzbich, M.; Wuchter, P.; Herfarth, K.; Egerer, G.; Ho, A.D.; Witzens-Harig, M. The influence of rituximab, high-dose therapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation, and age in patients with primary CNS lymphoma. Ann. Hematol. 2015, 94, 1853–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonoda, Y.; Matsumoto, K.; Kakuto, Y.; Nishino, Y.; Kumabe, T.; Tominaga, T.; Katakura, R. Primary CNS lymphoma treated with combined intra-arterial ACNU and radiotherapy. Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 2007, 149, 1183–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taoka, K.; Okoshi, Y.; Sakamoto, N.; Takano, S.; Matsumura, A.; Hasegawa, Y.; Chiba, S. A nonradiation-containing, intermediate-dose methotrexate regimen for elderly patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma. Int. J. Hematol. 2010, 92, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiff, P.J.; Unger, J.M.; Cook, J.R.; Constine, L.S.; Couban, S.; Stewart, D.A.; Shea, T.C.; Porcu, P.; Winter, J.N.; Kahl, B.S.; et al. Autologous transplantation as consolidation for aggressive non-hodgkin’s lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1681–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponzoni, M.; Issa, S.; Batchelor, T.T.; Rubenstein, J.L. Beyond high-dose methotrexate and brain radiotherapy: Novel targets and agents for primary CNS lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2014, 25, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alnahhas, I.; Jawish, M.; Alsawas, M.; Zukas, A.; Prokop, L.; Murad, M.H.; Malkin, M. Autologous stem-cell transplantation for primary central nervous system lymphoma: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2019, 19, e129–e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Hong, J.; Hwang, I.; Ahn, J.Y.; Cho, E.Y.; Park, J.; Cho, E.K.; Shin, D.B.; Lee, J.H. Comprehensive geriatric assessment in elderly patients with newly diagnosed aggressive non-hodgkin lymphoma treated with multi-agent chemotherapy. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2015, 6, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).