Sensitivity Analysis of Process Parameters on Deposition Quality and Multi-Objective Prediction in Ion-Assisted Electron Beam Evaporation of Ta2O5 Films

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Details and Theoretical Method

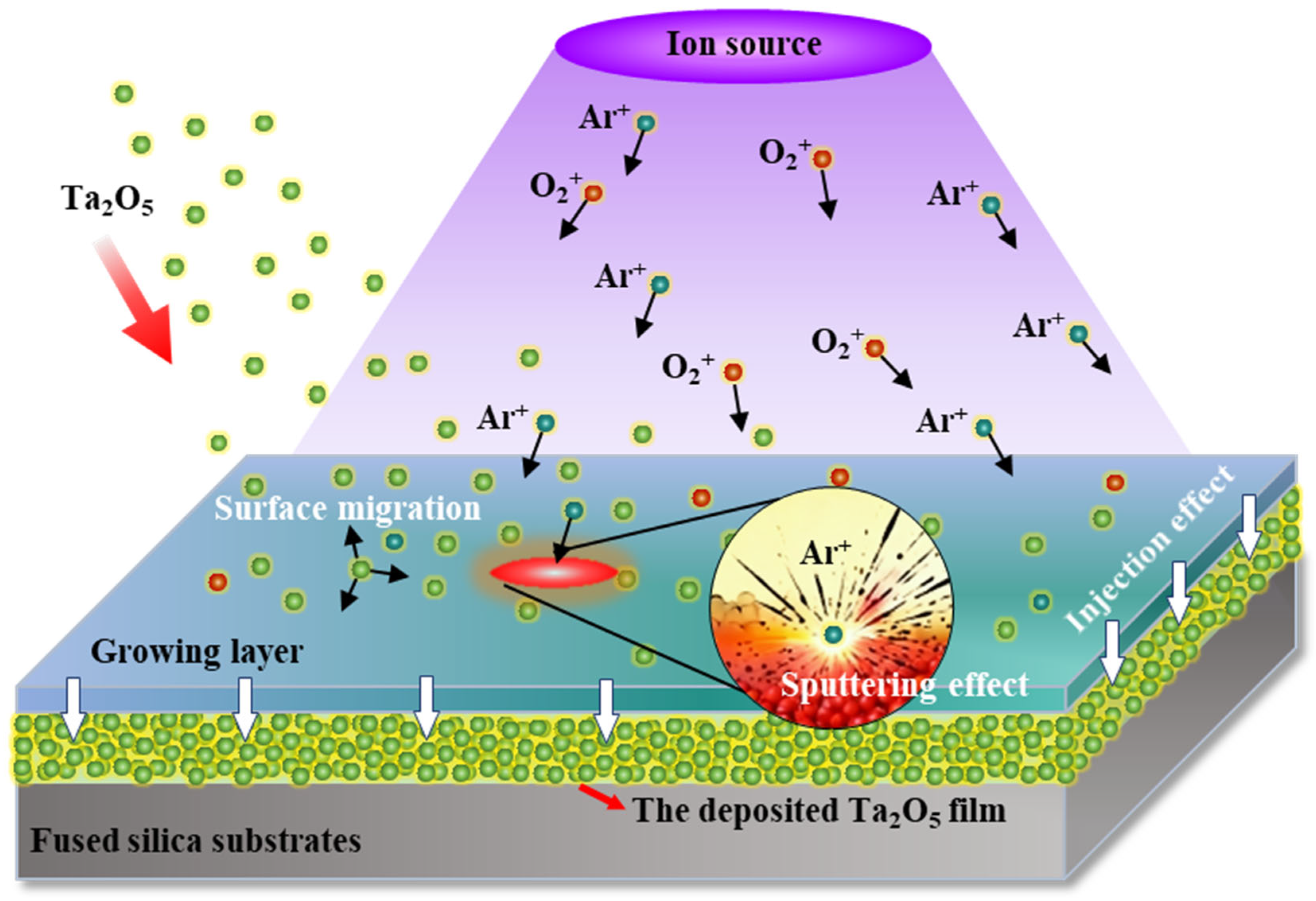

2.1. Ta2O5 Films on the FSS Prepared by IAD-EBE Experiments

2.2. Characterization of Rq and n in Ta2O5 Films

2.3. Deposition Quality Prediction Achieved by Physics-Informed Bayesian Optimization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Mechanistic Analysis of the Influence of Plasma Energy Fields on Rq and n of Ta2O5 Films

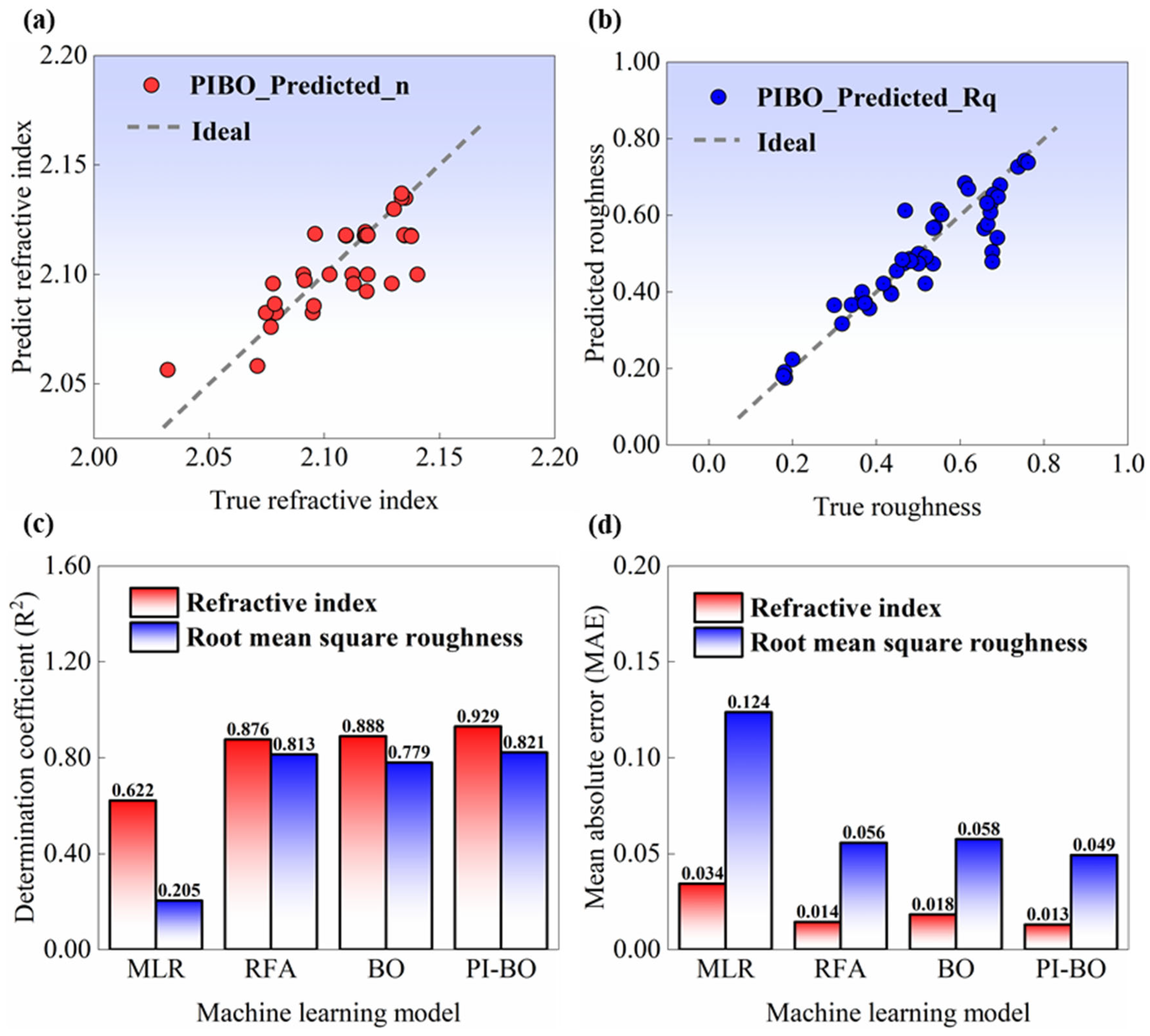

3.2. PI-BO-Based Prediction and Experimental Validation of Rq and n for Ta2O5 Films

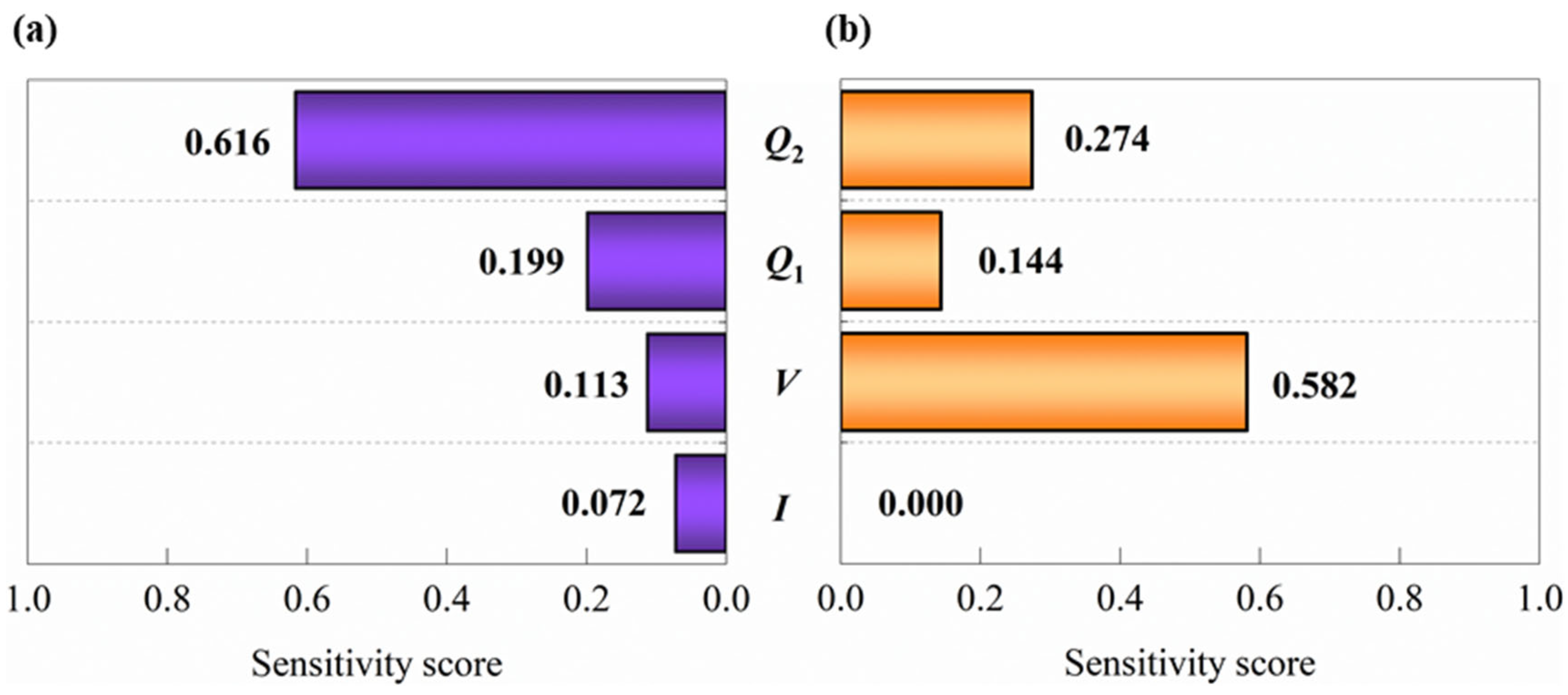

3.3. Sensitivity Analysis and Optimization of Process Parameters for Deposition Quality

4. Conclusions

- The regulating effects of ion source parameters (V, I, Q1 and Q2) on n and Rq of Ta2O5 films are clarified. As V increases, the overall trend of n and Rq shows a fluctuating decline. The increase in Q2 is conducive to enhancing the oxidation degree of the film, inhibiting the thermal decomposition of Ta2O5 and oxygen vacancies under high temperature and ion bombardment, while I and Q1 exert secondary influences via flux-induced damage and discharge stability.

- The proposed method is grounded in the analysis of deposition mechanisms and Bayesian optimization theory. An approach for predicting the deposition quality of Ta2O5 films and characterizing the features of process parameters is developed, specifically designed for small-sample datasets. The validation results of the PI-BO method show that the R2/MAE of the prediction models for n and Rq reach 0.9273/0.0133 and 0.8214/0.0492, respectively. The PI-BO model has high robustness and strong generalization capability.

- For n/Rq, the weight factors of V, I, Q1, and Q2 are 0.616/0.274, 0.199/0.144, 0.113/0.582, and 0.072/0.000, respectively. V and Q2 are identified as the dominant factors for regulating the deposition quality of Ta2O5 films. The preferred ranges for V and Q2 are determined to be 600~700 V and 70~80 sccm, respectively. Within the above ranges, Ta2O5 films exhibit high refractive index (n > 2.15) and low surface roughness (Rq: 0.2~3 nm).

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ta2O5 | Tantalum pentoxide |

| n | Refractive index |

| IAD-EBE | Ion-assisted electron beam evaporation |

| V | Assisting ion source beam voltage |

| ML | Machine learning |

| TFNNs | Thin-film neural networks |

| I | Assisting ion source beam current |

| Rq | Root-mean-square surface roughness |

| PI-BO | Physics-informed Bayesian optimization |

| FSS | Fused silica substrate |

| RF | Radio frequency |

| QCM | Quartz crystal microbalance |

| Q1 | Argon flow rate |

| Q2 | Oxygen flow rate |

| AFM | Atomic force microscopy |

| GP | Gaussian process |

| MLR | Multivariate linear regression |

| RFA | Random forest algorithm |

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

References

- Jena, S.; Tokas, R.B.; Rao, K.D.; Thakur, S.; Sahoo, N.K. Annealing effects on microstructure and laser-induced damage threshold of HfO2/SiO2 multilayer mirrors. Appl. Opt. 2016, 55, 6108–6114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Yin, Z.; Zhao, L.; Cheng, J.; Chen, M.; Liu, Q.; Yang, D.; Chen, G.; Hu, J.; Chen, J. Repair-mechanism and strategy-customization during micro-milling of flawed potassium dihydrogen phosphate. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2025, 290, 110110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheikh, A.; Gonçalves, J.; Labbé, C.; Portier, X.; Marie, P.; Frilay, C.; Debieu, O.; Duprey, S.; Jadwisienczak, W.; Ingram, D.; et al. Tailoring structural and optical properties of Ta2O5 thin films via radio frequency magnetron sputtering for high-refractive index transparent materials. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1040, 183273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangalakurti, L.; Venugopal Reddy, K.; Chhabra, I.M. Optimization of dielectric films with dual ion beam sputtering deposition for high reflectivity mirrors. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 43, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Chen, G.; Chen, M.; Cheng, J.; Chen, G.; Chen, M.; Zhao, L.; Xu, Q.; Yuan, X.; Liu, Z.; et al. Overview of advanced optical manufacturing techniques applied in regulating laser damage precursors in nonlinear functional KHxD2-xPO4 crystal. Light Adv. Manuf. 2025, 6, 546–574. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, X.; Shao, J.; Yi, K.; Hu, Y.; Hu, G.; Grilli, M.L.; Chai, Y. The formation of transient defects during high power laser-coating interaction revealed by the variation of electron beam evaporated coatings’ optical constants with temperature. Opt. Commun. 2022, 516, 127945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; He, Y.; Li, K.; Zhou, H.; Xiong, Y. Study on thickness uniformity of Ta2O5 film evaporated on the inner-face of a hemispherical substrate. Optoelectron. Lett. 2021, 17, 673–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Yin, Z.; He, Z.; Cheng, J.; Zhao, L.; Liu, Q.; Ding, W.; Yang, D.; Chen, G.; Chen, M. Characterization-method and repair-mechanism of atomic defects in potassium dihydrogen phosphate. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2025, 308, 110950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Xue, Y.; Huang, C.; Xia, Z.; Zhang, G.; Fu, Z. Optical properties and elemental composition of Ta2O5 thin films. In Proceedings of the 2009 Symposium on Photonics and Optoelectronics, Wuhan, China, 14–16 August 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Song, R.; Hu, J.; Peng, Y.; Xiao, Y.A.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, K.; Jiang, Y.; Xia, X.; Xia, Z. Fabrication of ultra-low-absorption thin films via ion beam-assisted electron-beam evaporation. High Power Laser Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, E38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macleod, H.A. Chapter 1—Recent developments in deposition techniques for optical thin films and coatings. In Optical Thin Films and Coatings, 2nd ed.; Piegari, A., Flory, F., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Farhan, M.S.; Zalnezhad, E.; Bushroa, A.R. Properties of Ta2O5 thin films prepared by ion-assisted deposition. Mater. Res. Bull. 2013, 48, 4206–4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Zhao, Q.; Cheng, J.; Zhao, L.; Chen, M.; Liu, Q.; Yang, D.; Chen, G. Understanding the friction behavior and surface characteristic in multiple ball-end milling passes of soft-brittle KH2PO4 optics. Tribol. Int. 2025, 211, 110836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Li, D.; Fan, H.; Deng, J.; Qi, J.; Yi, P.; Qiang, Y. Effects of different post-treatment methods on optical properties, absorption and nanosecond laser-induced damage threshold of Ta2O5 films. Thin Solid Film. 2015, 580, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Zhu, M.; Chai, Y.; Liu, T.; Shi, J.; Du, W.; Shao, J. Optical and femtosecond laser-induced damage-related properties of Ta2O5-based oxide mixtures. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 957, 170352. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Xue, Y.; Guo, P.; Wang, H.; Ma, Z. Optical properties and microstructure of Ta2O5 thin films prepared by ion assisted electron beam evaporation. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol.-Mater. Sci. Ed. 2008, 23, 632–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Zhang, M.; Xiao, J.; Wang, F. Research on the Performance of Nano-Scale AR Films for Airborne Optical Cable Components Based on Process Parameter Regulation; SPIE: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, H.; Zhao, L.; Cheng, J.; Chen, M.; Liu, Q. Material removal mechanisms affected by milling modes for defective KDP surfaces. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2024, 48, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, W.; Hong, R.; Wang, K.; Wang, M.; Wang, Q.; Yi, K.; Shao, J. Reduction of absorption of Ta2O5 monolayers through the suppression of structural defects by employing an appropriate ionic oxygen concentration. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Kong, M.; Jing, J. High-performance Ta2O5 films prepared by plasma ion-assisted deposition for low-absorption optics. Opt. Contin. 2024, 3, 1679–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiryont, H.; Sites, J.R. Effects of Deposition Parameters on Optical Properties of Ta2O5 Films Deposited Ion-Beam-Sputtering. In Proceedings of the Third Topical Meeting on Optical Interference Coatings, Monterey, CA, USA, 17–19 April 1984; Optica Publishing Group: Washington, DC, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sakiew, W.; Schwerdtner, P.; Jupé, M.; Pflug, A.; Ristau, D. Impact of ion species on ion beam sputtered Ta2O5 layer quality parameters and on corresponding process productivity: A preinvestigation for large-area coatings. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2021, 39, 063402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Blake, C.; Mravac, L.; Zhang, F.; Chen, Y.; Yang, S. A Machine Learning Approach Capturing Hidden Parameters in Autonomous Thin-Film Deposition. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.18721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuna, J.; Vuorinen, M.; Isoaho, R.; Aho, A.; Mäkelä, S.; Hietalahti, A.; Anttola, E.; Tukiainen, A.; Guina, M. Optimization of reactive ion beam sputtered Ta2O5 for III–V compounds. Thin Solid Film. 2022, 763, 139601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Ma, M.; Guo, L.J. Optical multilayer thin film structure inverse design: From optimization to deep learning. iScience 2025, 28, 112222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazrin, S.N.; Doroody, C.; Burhanuddin, L.A.; Jothi, N.; Ibrahim, N.; Zaman, H.B.; Tahir, M.H.M.; Soudagar, M.; Ramesh, S. Machine learning-driven prediction of optical and physical properties in lanthanum and gold-doped zinc borotellurite glasses for optoelectronic applications. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 30370–30383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.T.; Mai, H.V.; Nguyen, H.M.; Duong, D.C.; Vu, V.H.; Hoang, N.N.; Nguyen, M.V.; Mai, T.A.; Tong, H.D.; Nguyen, H.Q.; et al. Machine-learning reinforcement for optimizing multilayered thin films: Applications in designing broadband antireflection coatings. Appl. Opt. 2022, 61, 3328–3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, H.; Ladhe, P.D.; Misra, S. Machine Learning-Enabled Optical Property Prediction of Thin Films Using Spectral Data Extraction from Scientific Literature. ACS Appl. Opt. Mater. 2025, 3, 2544–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Chen, A.; Li, T.; Chu, J.; Tang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, M.; Shen, T.; Zheng, M.; Guan, F.; et al. Thin-film neural networks for optical inverse problem. Light Adv. Manuf. 2021, 2, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, A.; Osamu, Y.; Chen, L. Multilayer optical thin film design with deep Q learning. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirvonen, J. Ion Beam Assisted Deposition for Optical Coatings: R&D to Production. In Proceedings of the 37th Annual Technical Conference of the Society of Vacuum Coaters, Albuquerque, NM, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mcneil, J.R.; Barron, A.C.; Wilson, S.; Herrmann, W. Ion-assisted deposition of optical thin films: Low energy vs high energy bombardment. Appl. Opt. 1984, 23, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Randel, E.; Vajente, G.; Ananyeva, A.; Gustafson, E.; Markosyan, A.; Bassiri, R.; Fejer, M.; Menoni, C. Modifications of ion beam sputtered tantala thin films by secondary argon and oxygen bombardment. Appl. Opt. 2020, 59, A150–A154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.-H.; Hwangbo, C.K.; Son, Y.B.; Moon, I.C.; Kang, G.M.; Lee, K.S. Optical properties of Ta2O5 thin films deposited by plasma ion-assisted deposition. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2005, 46, S187–S191. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Q.; Huang, M.; Deng, S.; Zhang, S.; Li, G. Effects of oxygen flows on optical properties, micro-structure and residual stress of Ta2O5 films deposited by DIBS. Optik 2018, 166, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, Y.; Feng, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, D.; Cui, Y.; Shao, J. Effect of ionic oxygen concentration on properties of SiO2 and Ta2O5 monolayers deposited by ion beam sputtering. Opt. Mater. 2023, 136, 113349. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Robertson, J. Comparison of oxygen vacancy defects in crystalline and amorphous Ta2O5. Microelectron. Eng. 2015, 147, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, Y.-H.; Chou, C.-C.; Shieu, F.-S. Preparation and optical properties of Ta2O5-x thin films. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2008, 107, 524–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.J.; Macleod, H.A.; Netterfield, R.P.; Pacey, C.G.; Sainty, W.G. Ion-beam-assisted deposition of thin films. Appl. Opt. 1983, 22, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.-G.; Liu, Z.; Liu, W.-C.; Li, M.; Zhang, S.B.; Luo, C.X.; Zhang, C.J. Research on the properties of Ta2O5 optical films prepared with APS plasma assisted deposition. In Proceedings of the Seventh Asia Pacific Conference on Optics Manufacture and 2021 International Forum of Young Scientists on Advanced Optical Manufacturing (APCOM and YSAOM 2021), Shanghai, China, 28–31 October 2021; SPIE: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Manova, D.; Gerlach, J.W.; Mändl, S. Thin Film Deposition Using Energetic Ions. Materials 2010, 3, 4109–4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregoire, J.; Lobovsky, M.; Heinz, M.; DiSalvo, F.; Dover, R. Resputtering phenomena and determination of composition in codeposited. Phys. Rev. B—Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2007, 76, 195437. [Google Scholar]

- Jambur, V.; Wang, Z.; Sunderland, J.; Im, S.; Hu, X.; Akinyemi, S.; Perepezko, J.H.; Voyles, P.M.; Szlufarska, I. Ion beam assisted deposition of a thin film metallic glass. Thin Solid Film. 2025, 812, 140612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.-W.; Xu, C.; Tian, Z.-X.; Luo, D.; Shen, G.-D. Effects of Ar ion assisted deposition on the optical and electrical characteristics of electron-beam-evaporated amorphous Si films. Optoelectron. Lett. 2006, 2, 358–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Process Parameters | Symbol | Unit | Value Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assisting ion source beam voltage | V | V | 500~1400 |

| Assisting ion source beam current | I | mA | 1200~1600 |

| Argon (Ar) flow rate | Q1 | sccm | 0~20 |

| Oxygen (O2) flow rate | Q2 | sccm | 60~100 |

| Constraint Rule | Output | Parameter Condition | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage–current synergy rule | Rq | V ∈ [900, 1000] V & I ∈ [1280, 1320] mA | 0.20 |

| n | V ∈ [800, 1200] V & I ∈ [1300, 1500] mA | 0.22 | |

| Power optimization rule | Rq | P = V × I/1000 ∈ [900, 1100] W | 0.26 |

| n | P = Voltage × Current/1000 ∈ [1000, 1500] W | 0.22 | |

| Ar flow rate control rule | Rq | Q1 ∈ [7, 9] sccm | 0.30 |

| n | Q1 = 0 sccm | 0.18 | |

| O2 flow rate priority rule | Rq | Q2 ∈ [77, 80] sccm | 0.18 |

| n | Q2 > 90 sccm | 0.25 | |

| Q2/Q1 ratio rule | Rq | Q2/Q1 ∈ [8, 12] (Q1 ≥ 5 sccm) | 0.15 |

| n | Q2/Q1 > 10 | 0.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wei, Y.; Li, J.; Ma, W.; Lei, H.; Zhang, F.; Luo, Z.; Liu, H.; Huang, X.; Zhao, L.; Chen, M. Sensitivity Analysis of Process Parameters on Deposition Quality and Multi-Objective Prediction in Ion-Assisted Electron Beam Evaporation of Ta2O5 Films. Micromachines 2026, 17, 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17020166

Wei Y, Li J, Ma W, Lei H, Zhang F, Luo Z, Liu H, Huang X, Zhao L, Chen M. Sensitivity Analysis of Process Parameters on Deposition Quality and Multi-Objective Prediction in Ion-Assisted Electron Beam Evaporation of Ta2O5 Films. Micromachines. 2026; 17(2):166. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17020166

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Yaowei, Jianchong Li, Wenze Ma, Hongqin Lei, Fei Zhang, Zhenfei Luo, Henan Liu, Xianghui Huang, Linjie Zhao, and Mingjun Chen. 2026. "Sensitivity Analysis of Process Parameters on Deposition Quality and Multi-Objective Prediction in Ion-Assisted Electron Beam Evaporation of Ta2O5 Films" Micromachines 17, no. 2: 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17020166

APA StyleWei, Y., Li, J., Ma, W., Lei, H., Zhang, F., Luo, Z., Liu, H., Huang, X., Zhao, L., & Chen, M. (2026). Sensitivity Analysis of Process Parameters on Deposition Quality and Multi-Objective Prediction in Ion-Assisted Electron Beam Evaporation of Ta2O5 Films. Micromachines, 17(2), 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17020166