Optical Intensity Discrimination with Engineered Interface States in Topological Photonic Crystals

Abstract

1. Introduction

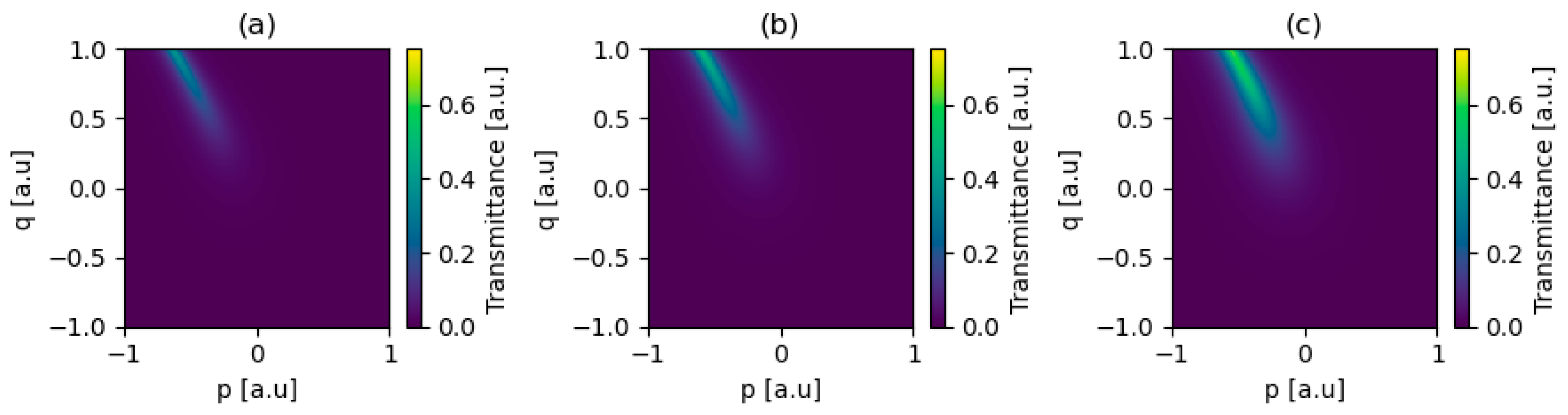

2. Numerical Simulation

2.1. Nonlinear and Linear Properties of Graphene

2.2. Weyl Point and Optical Properties

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TPP | Tamm Plasmon Polariton |

| TMM | Transfer Matrix Method |

| F-P | Fabry–Perot |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene (Teflon) |

| DBR | Distributed Bragg Reflector |

Appendix A

References

- Tong, R.; Zhang, R.; Yuan, P.; Li, S.; Liu, L.; Zhao, Y. Tamm Plasmon Polaritons: Principle, Excitation, and Sensing Applications. Laser Photonics Rev. 2025, e02507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.M.; Talukder, M.A. Tamm and Surface Plasmon Hybrid Modes in Anisotropic Graphene-Photonic-Crystal Structure for Hemoglobin Detection. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 14261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, C.; Sang, T.; Yang, G.; Wang, Y. Topological Tamm Edge States. Opt. Lett. 2025, 50, 3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, C.; Jena, S.; Udupa, D.V.; Rao, K.D. Tamm Plasmon Polariton in Planar Structures: A Brief Overview and Applications. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 159, 108928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubitidze, T.; Britton, W.A.; Negro, L.D. Enhanced Nonlinearity of Epsilon-Near-Zero Indium Tin Oxide Nanolayers with Tamm Plasmon-Polariton States. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2024, 12, 2301669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubitidze, T.; Chawla, S.; Dal Negro, L. Enhancement of the Third Harmonic Generation Efficiency of ITO Nanolayers Coupled to Tamm Plasmon Polaritons. APL Photonics 2025, 10, 026110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Tan, Y.J.; Wang, W.; Tan, T.C.; Yan, R.; Zhang, L.; Singh, R. Interface Topology Driven Loss Minimization in Integrated Photonics: THz Ultrahigh- Q Cavities and Waveguides. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2503460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kou, N.; Yu, S. Radiation of Topological Waveguide Induced by Aperture Coupling Effect. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 192, 114071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janaszek, B.; Tyszka-Zawadzka, A.; Szczepański, P. Graphene-Based Hyperbolic Metamaterial Acting as Tunable THz Power Limiter. IEEE J. Select. Top. Quantum Electron. 2023, 29, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.T.; Feng, W.; Liu, Z.; Cao, J.C. Voltage-Adjustable Terahertz Hyperbolic Metamaterial Based on Graphene and Doped Silicon. AIP Adv. 2019, 9, 015108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; So, S.; Hu, G.; Kim, M.; Badloe, T.; Cho, H.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Qiu, C.-W.; Rho, J. Hyperbolic Metamaterials: Fusing Artificial Structures to Natural 2D Materials. eLight 2022, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorgholam-Khanjari, S.; Zarrabi, F.B. Reconfigurable Vivaldi THz Antenna Based on Graphene Load as Hyperbolic Metamaterial for Skin Cancer Spectroscopy. Opt. Commun. 2021, 480, 126482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Guo, T.; Zhu, L.; Chen, P.-Y.; Argyropoulos, C. Tunable THz Generation and Enhanced Nonlinear Effects with Active and Passive Graphene Hyperbolic Metamaterials. In Proceedings of the Smart Photonic and Optoelectronic Integrated Circuits XXII, San Francisco, CA, USA, 3–6 February 2020; He, S., Vivien, L., Eds.; SPIE: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, H. The Tailored Saturated-Unsaturateddefect Modes Obtained by Nonlinear Threshold Light in Graphene-Based Hyperbolicmetamaterial. IEEE J. Select. Top. Quantum Electron. 2021, 29, 5100107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozina, O.N.; Melnikov, L.A.; Nefedov, I.S. A Theory for Terahertz Lasers Based on a Graphene Hyperbolic Metamaterial. J. Opt. 2020, 22, 095003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Lin, Q.; Xiao, M.; Fan, S. Synthetic Dimension in Photonics. Optica 2018, 5, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanikaev, A.B.; Alù, A. Topological Photonics: Robustness and Beyond. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janaszek, B.; Tyszka-Zawadzka, A.; Szczepański, P. Utilizing Fermi Arc States in Photonic Crystals for Ultrasensitive Gas Detection. Opt. Express 2025, 33, 51319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xiao, M.; Liu, H.; Zhu, S.; Chan, C.T. Optical Interface States Protected by Synthetic Weyl Points. Phys. Rev. X 2017, 7, 031032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, O.C.; Naidu, G.N.; Bowman, A.R.; Dayi, E.N.; Tagliabue, G. Decoupling Optical and Thermal Dynamics in Dielectric Metasurfaces for Self-Encoded Photonic Control. Laser Photonics Rev. 2025, 19, e01014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailov, S.A.; Ziegler, K. Nonlinear Electromagnetic Response of Graphene: Frequency Multiplication and the Self-Consistent-Field Effects. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2008, 20, 384204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, G.W. Dyadic Green’s Functions for an Anisotropic, Non-Local Model of Biased Graphene. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2008, 56, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasari, H.; Abrishamian, M.S. Terahertz Bistability and Multistability in Graphene/Dielectric Fibonacci Multilayer. Appl. Opt. 2017, 56, 5313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, Q.; Wei, Z.; Li, H. Tunable Terahertz Coherent Perfect Absorption in a Monolayer Graphene. Opt. Lett. 2014, 39, 6269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouillet, J.; Papadakis, G.T.; Atwater, A.H.A. Experimental Demonstration of Tunable Graphene-Polaritonic Hyperbolic Metamaterial. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 30225–30232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, T.; Petrone, N.; McMillan, J.F.; van der Zande, A.; Yu, M.; Lo, G.Q.; Kwong, D.L.; Hone, J.; Wong, C.W. Regenerative Oscillation and Four-Wave Mixing in Graphene Optoelectronics. Nat. Photon 2012, 6, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Mu, H.; Li, X.; Yuan, J.; Chen, J.; Xiao, S.; Bao, Q.; Gao, Y.; He, J. Observation of Large Nonlinear Responses in a Graphene-Bi2Te3 Heterostructure at a Telecommunication Wavelength. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 108, 221901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalchuk, O.; Gong, S.; Moon, H.; Song, Y.-W. Graphene-Advanced Functional Devices for Integrated Photonic Platforms. npj Nanophoton. 2025, 2, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, K.Y.; Liu, X.; Qiu, J. A Comparison for Saturable Absorbers: Carbon Nanotube Versus Graphene. Adv. Photonics Res. 2022, 3, 2200023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbach, A.V. Nonlinear Graphene Plasmonics: Amplitude Equation for Surface Plasmons. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 87, 013830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Yin, X.; Ulin-Avila, E.; Geng, B.; Zentgraf, T.; Ju, L.; Wang, F.; Zhang, X. A Graphene-Based Broadband Optical Modulator. Nature 2011, 474, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorsh, I.V.; Mukhin, I.S.; Shadrivov, I.V.; Belov, P.A.; Kivshar, Y.S. Hyperbolic Metamaterials Based on Multilayer Graphene Structures. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 87, 075416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, P.; Yariv, A.; Hong, C.-S. Electromagnetic Propagation in Periodic Stratified Media I General Theory*. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1977, 67, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grytsenko, K.; Kolomzarov, Y.; Lytvyn, P.; Kondratenko, O.; Sopinskyy, M.; Lebedyeva, I.; Niemczyk, A.; Baranovska, J.; Moszyński, D.; Villringer, C.; et al. Optical and Mechanical Properties of Thin PTFE Films, Deposited from a Gas Phase. Macro Mater. Eng. 2023, 308, 2200617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foggiato, J. Chemical Vapor Deposition of Silicon Dioxide Films. In Handbook of Thin Film Deposition Processes and Techniques; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 111–150. ISBN 978-0-8155-1442-8. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Gong, X.; Gai, J. Progress and Challenges in Transfer of Large-Area Graphene Films. Adv. Sci. 2016, 3, 1500343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplas, T.; Karvonen, L.; Ahmadi, S.; Amirsolaimani, B.; Mehravar, S.; Peyghambarian, N.; Kieu, K.; Honkanen, S.; Lipsanen, H.; Svirko, Y. Optical Characterization of Directly Deposited Graphene on a Dielectric Substrate. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Janaszek, B.; Szczepański, P. Optical Intensity Discrimination with Engineered Interface States in Topological Photonic Crystals. Micromachines 2026, 17, 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17020165

Janaszek B, Szczepański P. Optical Intensity Discrimination with Engineered Interface States in Topological Photonic Crystals. Micromachines. 2026; 17(2):165. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17020165

Chicago/Turabian StyleJanaszek, Bartosz, and Paweł Szczepański. 2026. "Optical Intensity Discrimination with Engineered Interface States in Topological Photonic Crystals" Micromachines 17, no. 2: 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17020165

APA StyleJanaszek, B., & Szczepański, P. (2026). Optical Intensity Discrimination with Engineered Interface States in Topological Photonic Crystals. Micromachines, 17(2), 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17020165