Enhancement of Piezoelectric Properties in Electrospun PVDF Nanofiber Membranes via In Situ Doping with ZnO or BaTiO3

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Optimization of Electrospinning Processing Parameters

2.3. Preparation of Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) and Composite PVDF Nanofiber Membranes

2.4. Characterization and Testing

3. Results

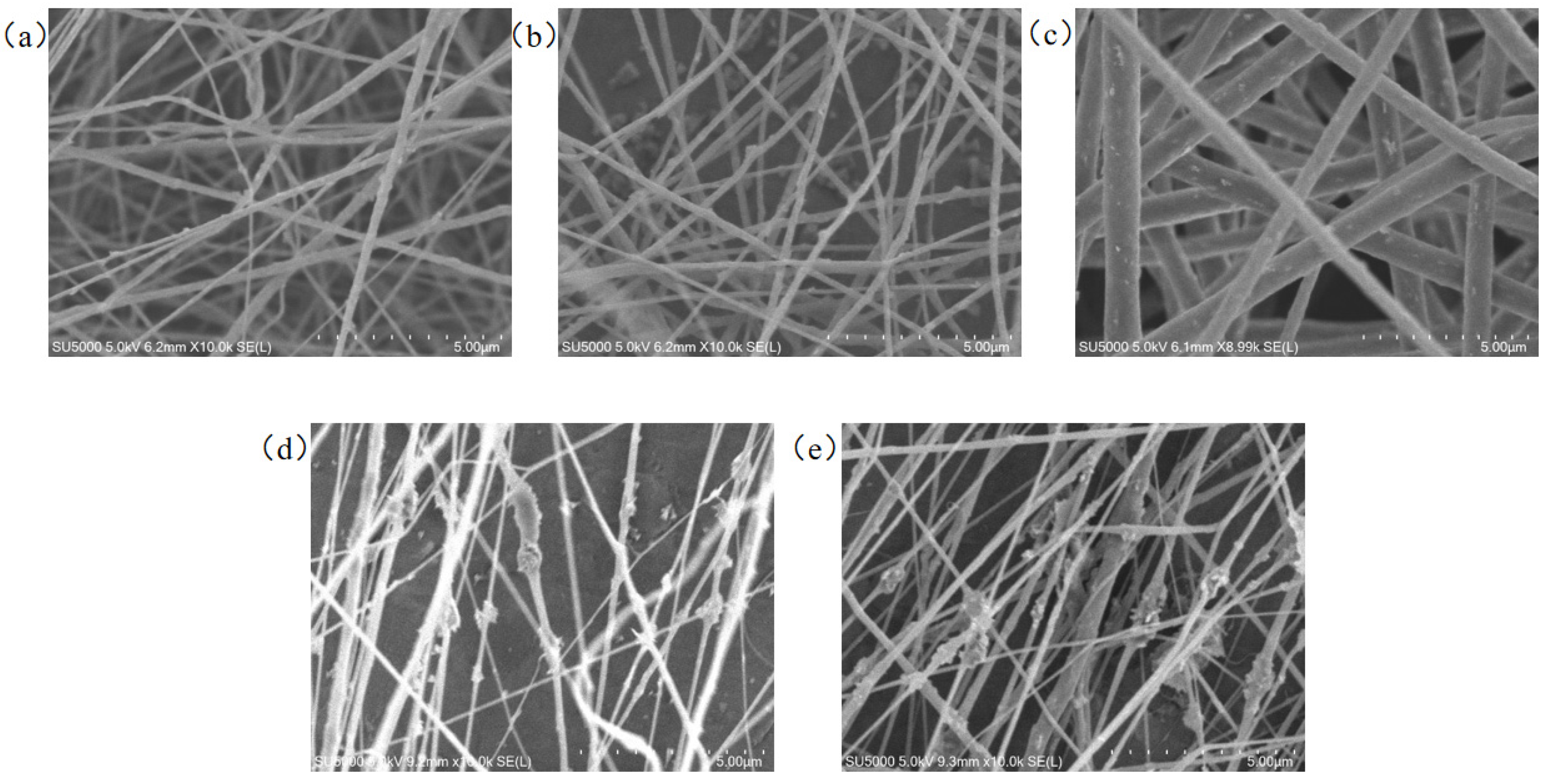

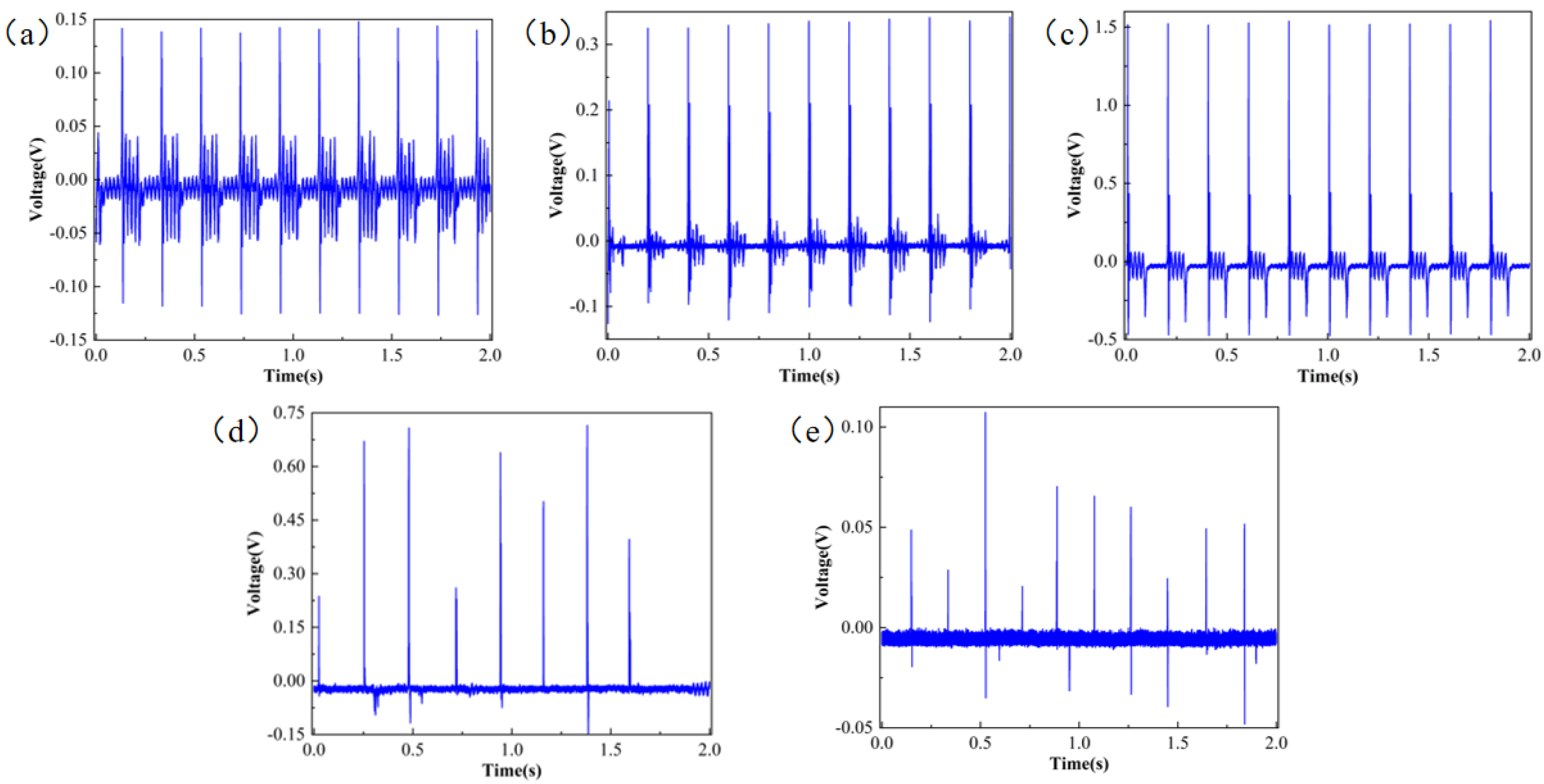

3.1. Characterization and Testing of PVDF Nanofibrous Membranes

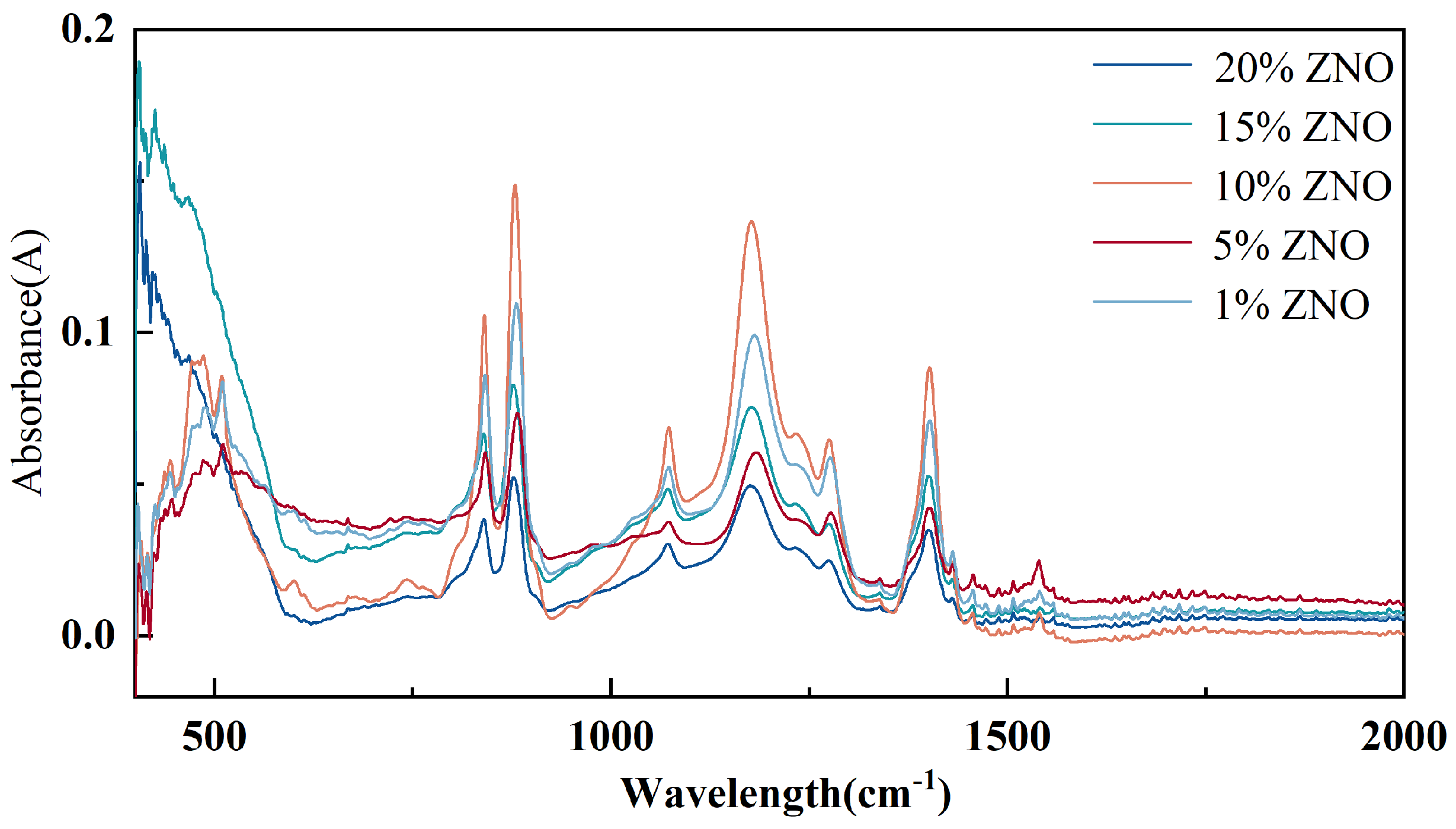

3.2. Characterization and Testing of PVDF/ZnO Composite Film

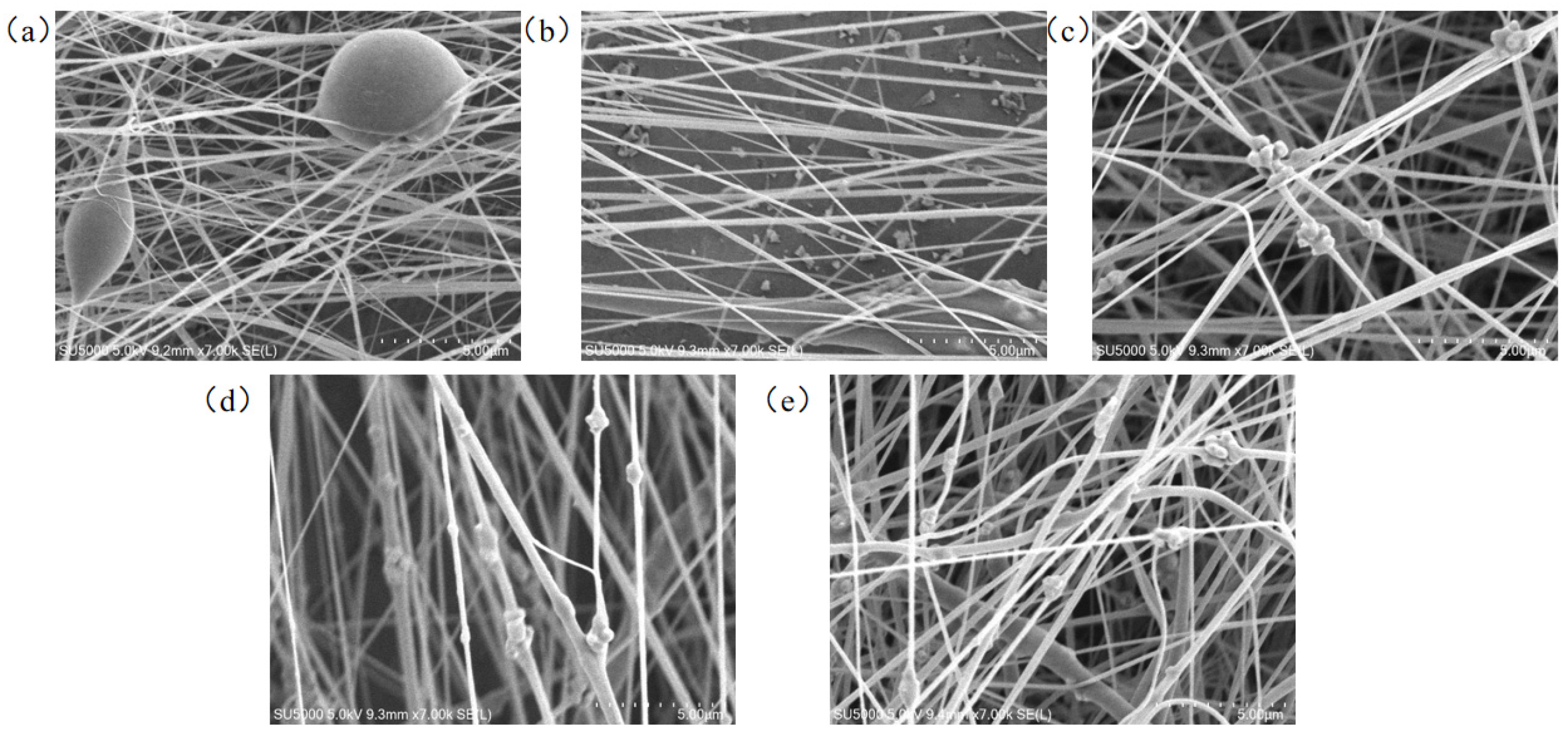

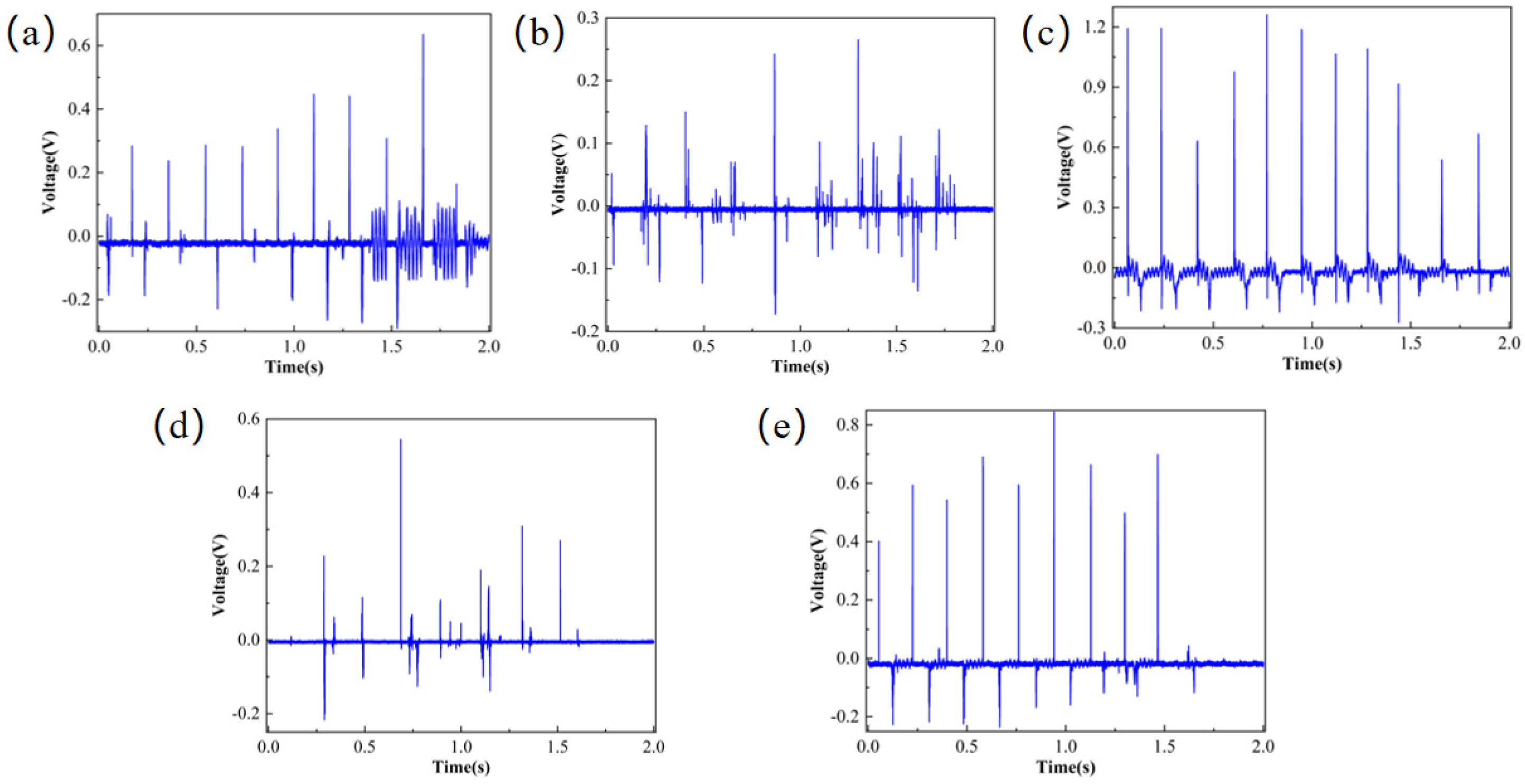

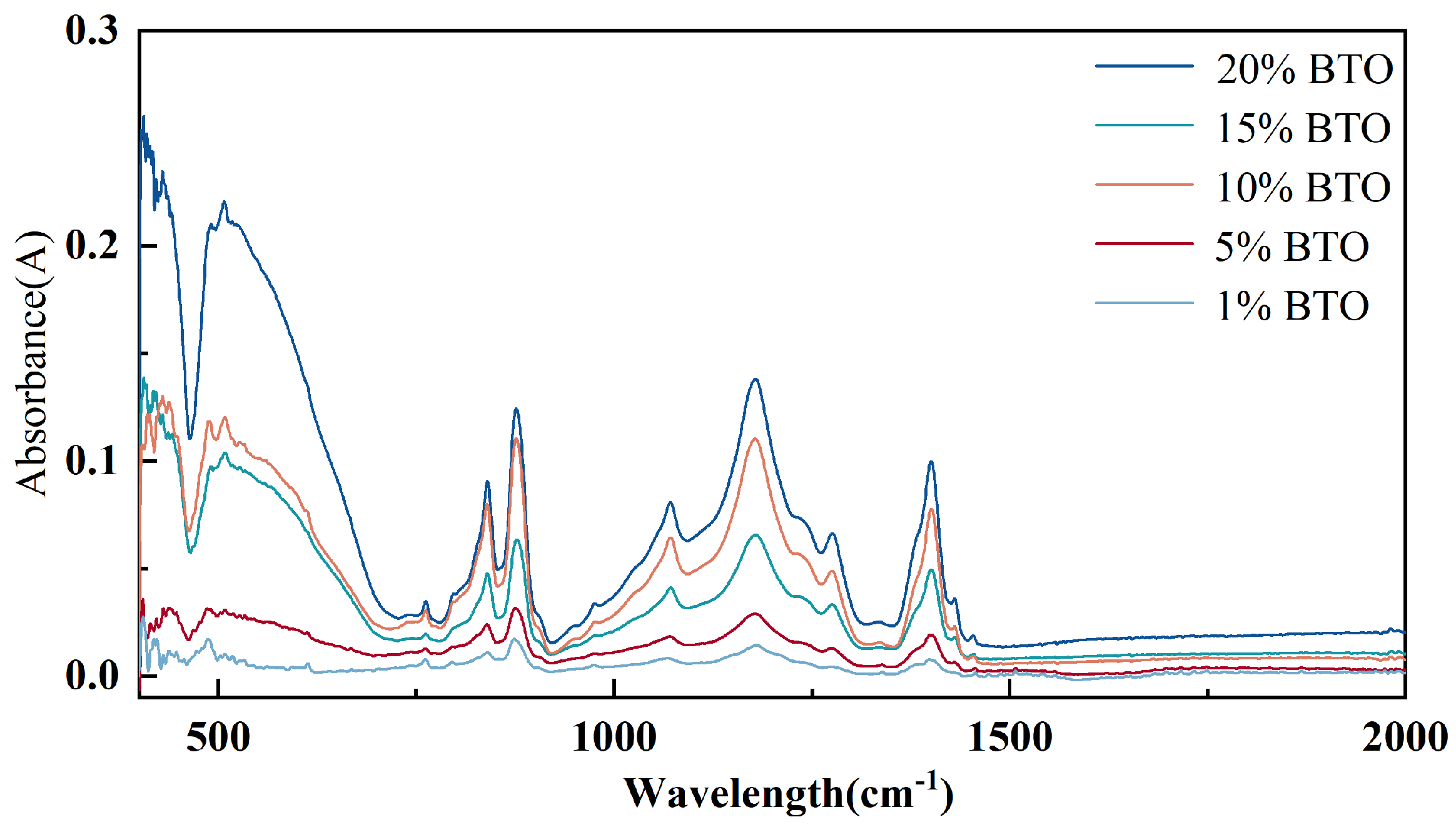

3.3. Characterization and Testing of PVDF/BTO Composite Film

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ueberschlag, P. PVDF piezoelectric polymer. Sens. Rev. 2001, 21, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrekrstos, A.; Muzata, T.S.; Ray, S.S. Nanoparticle-Enhanced β-Phase Formation in Electroactive PVDF Composites: A Review of Systems for Applications in Energy Harvesting, EMI Shielding, and Membrane Technology. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 7632–7651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Zhu, Z.; Rui, G.; Du, B.; Chen, D.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, L. Recent Progress on Structure Manipulation of Poly (vinylidene fluoride)-Based Ferroelectric Polymers for Enhanced Piezoelectricity and Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2301302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; You, M.; Yi, N.; Zhang, X.; Xiang, Y. Enhanced Piezoelectric Coefficient of PVDF-TrFE Films via In Situ Polarization. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 621540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahbab, N.; Naz, S.; Xu, T.-B.; Zhang, S. A Comprehensive Review of Piezoelectric PVDF Polymer Fabrications and Characteristics. Micromachines 2025, 16, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherzadeh, E.; Sherafat, Z.; Zebarjad, S.M.; Khodaei, A.; Yavari, S.A. Stimuli-responsive piezoelectricity in electrospun polycaprolactone (PCL)/polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) fibrous scaffolds for bone regeneration. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 23, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooti, A.; Costa, C.M.; Maceiras, A.; Pereira, N.; Tubio, C.R.; Vilas, J.L.; Besbes-Hentati, S.; Lanceros-Mendez, S. Magnetic and high-dielectric-constant nanoparticle polymer tri-composites for sensor applications. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 55, 16234–16246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolmaleki, H.; Agarwala, S. PVDF-BaTiO3 Nanocomposite Inkjet Inks with Enhanced β-Phase Crystallinity for Printed Electronics. Polymers 2020, 12, 2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arularasu, M.V.; Harb, M.; Vignesh, R.; Rajendran, T.V.; Sundaram, R. PVDF/ZnO hybrid nanocomposite applied as a resistive humidity sensor. Surf. Interfaces 2020, 21, 100780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, S.; Zameer, A.; Raja, M.A.Z.; Muhammad, K. Weighted differential evolution heuristics for improved multilayer piezoelectric transducer design. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 113, 107835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, T.; D’Souza, N.; Berman, D. Electrospun Fe3O4-PVDF Nanofiber Composite Mats for Cryogenic Magnetic Sensor Applications. Textiles 2021, 1, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.J.; Ding, W.Q.; Liu, J.Q.; Yang, B. Flexible PVDF based piezoelectric nanogenerators. J. Nano Energy 2020, 78, 105251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.H. Preparation, Performance Study of PVDF Blended Composite Membranes and Their Application in Flexible Sensors. J. Beijing Inst. Petrochem. Technol. 2023, 31, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.Z.; Li, G.J.; Qin, Q.; Mi, L.; Li, G.; Zheng, G.; Liu, C.; Li, Q.; Liu, X. Electrospun PVDF/PAN membrane for pressure sensor and sodiumion battery separator. J. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2021, 4, 1215–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Xian, S.; Yu, J.; Zhao, J.; Song, J.; Li, Z.; Hou, X.; Chou, X.; He, J. Synergistic enhancement properties of a flexible integrated PAN/PVDF piezoelectric sensor for human posture recognition. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, W.; Tan, B.; Zhu, C.; Ni, Y.; Fang, L.; Lu, C.; Xu, Z. Crystallinity and β phase fraction of PVDF in biaxially stretched PVDF/PMMA membrane. Polymers 2021, 13, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.; Sahoo, R.; Unnikrishnan, L.; Ramadoss, A.; Mohanty, S.; Nayak, S.K. Enhanced structural and dielectric behaviour of PVDF-PLA binary polymeric blend system. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 26, 101958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuova, U.; Tolegen, U.Z.; Inerbaev, T.M.; Karibayev, M.; Satanova, B.M.; Abuova, F.U.; Popov, A.I. A Brief Review of Atomistic Studies on BaTiO3 as a Photocatalyst for Solar Water Splitting. Ceramics 2025, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrone, E.; Araneo, R.; Notargiacomo, A.; Pea, M.; Rinaldi, A. ZnO Nanostructures and Electrospun ZnO-Polymeric Hybrid Nanomaterials in Biomedical, Health, and Sustainability Applications. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, B.; Seol, J.; Samuel, E.; Lim, W.; Park, C.; Aldalbahi, A.; El-Newehy, M.; Yoon, S.S. Supersonically sprayed PVDF and ZnO flowers with built-in nanocuboids for wearable piezoelectric nanogenerators. J. Nano Energy 2023, 112, 108447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indolia, A.P.; Gaur, M.S. Investigation of structural and thermal characteristics of PVDF/ZnO nanocomposites. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2013, 113, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffari, G.H.; Shawana, H.; Mumtaz, F.; Can, M.M. Electrical response of PVDF/BaTiO3 nanocomposite flexible free-standing membrane. J. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2023, 46, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Hassnain, J.G.; Hafsa, S.; Mumtaz, F.; Shahid Iqbal Khan, M.; Can, M.M. Manipulation of ferroelectric response of PVDF-TRFE free-standing flexible membrane due to incorporation of BaTiO3 nanoparticle fillers. J. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 16781–16799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.-X.; Gao, W.-C.; Ren, X.-M.; Ouyang, X.-Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wu, W.; Huang, C.-X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.-Y.; et al. A review of microphase separation of polyurethane: Characterization and applications. Polym. Test. 2022, 107, 107489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Jin, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ning, H.; Liu, X.; Alamusi; Hu, N. Recent advances in the preparation of PVDF-based piezoelectric materials. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2022, 11, 1386–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Solution | Concentration |

|---|---|

| PVDF | 10% |

| PVDF | 12% |

| PVDF | 14% |

| PVDF | 16% |

| PVDF | 18% |

| PVDF | 20% |

| Solution | Concentration |

|---|---|

| ZnO | 1% |

| ZnO | 5% |

| ZnO | 10% |

| ZnO | 15% |

| ZnO | 20% |

| BTO | 1% |

| BTO | 5% |

| BTO | 10% |

| BTO | 15% |

| BTO | 20% |

| Film Type | F(β) |

|---|---|

| 16% PVDF | 52.4% |

| 16% PVDF/1% ZnO | 50.1% |

| 16% PVDF/5% ZnO | 48.5% |

| 16% PVDF/10% ZnO | 52.8% |

| 16% PVDF/15% ZnO | 49.5% |

| 16% PVDF/20% ZnO | 51.7% |

| Film Type | F(β) |

|---|---|

| 16% PVDF | 52.4% |

| 16% PVDF/1% BTO | 52.8% |

| 16% PVDF/5% BTO | 49.9% |

| 16% PVDF/10% BTO | 51.4% |

| 16% PVDF/15% BTO | 50.9% |

| 16% PVDF/20% BTO | 51.2% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ouyang, Z.; Lin, J.; Rao, R.; Huang, G.; Zheng, G.; Cui, C. Enhancement of Piezoelectric Properties in Electrospun PVDF Nanofiber Membranes via In Situ Doping with ZnO or BaTiO3. Micromachines 2026, 17, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010012

Ouyang Z, Lin J, Rao R, Huang G, Zheng G, Cui C. Enhancement of Piezoelectric Properties in Electrospun PVDF Nanofiber Membranes via In Situ Doping with ZnO or BaTiO3. Micromachines. 2026; 17(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleOuyang, Zhizhao, Jinghua Lin, Renhao Rao, Guoqin Huang, Gaofeng Zheng, and Changcai Cui. 2026. "Enhancement of Piezoelectric Properties in Electrospun PVDF Nanofiber Membranes via In Situ Doping with ZnO or BaTiO3" Micromachines 17, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010012

APA StyleOuyang, Z., Lin, J., Rao, R., Huang, G., Zheng, G., & Cui, C. (2026). Enhancement of Piezoelectric Properties in Electrospun PVDF Nanofiber Membranes via In Situ Doping with ZnO or BaTiO3. Micromachines, 17(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi17010012