Analysis on the Air-Gap Magnetic Field and Force of the Linear Synchronous Motor with Different Winding Distribution

Abstract

1. Introduction

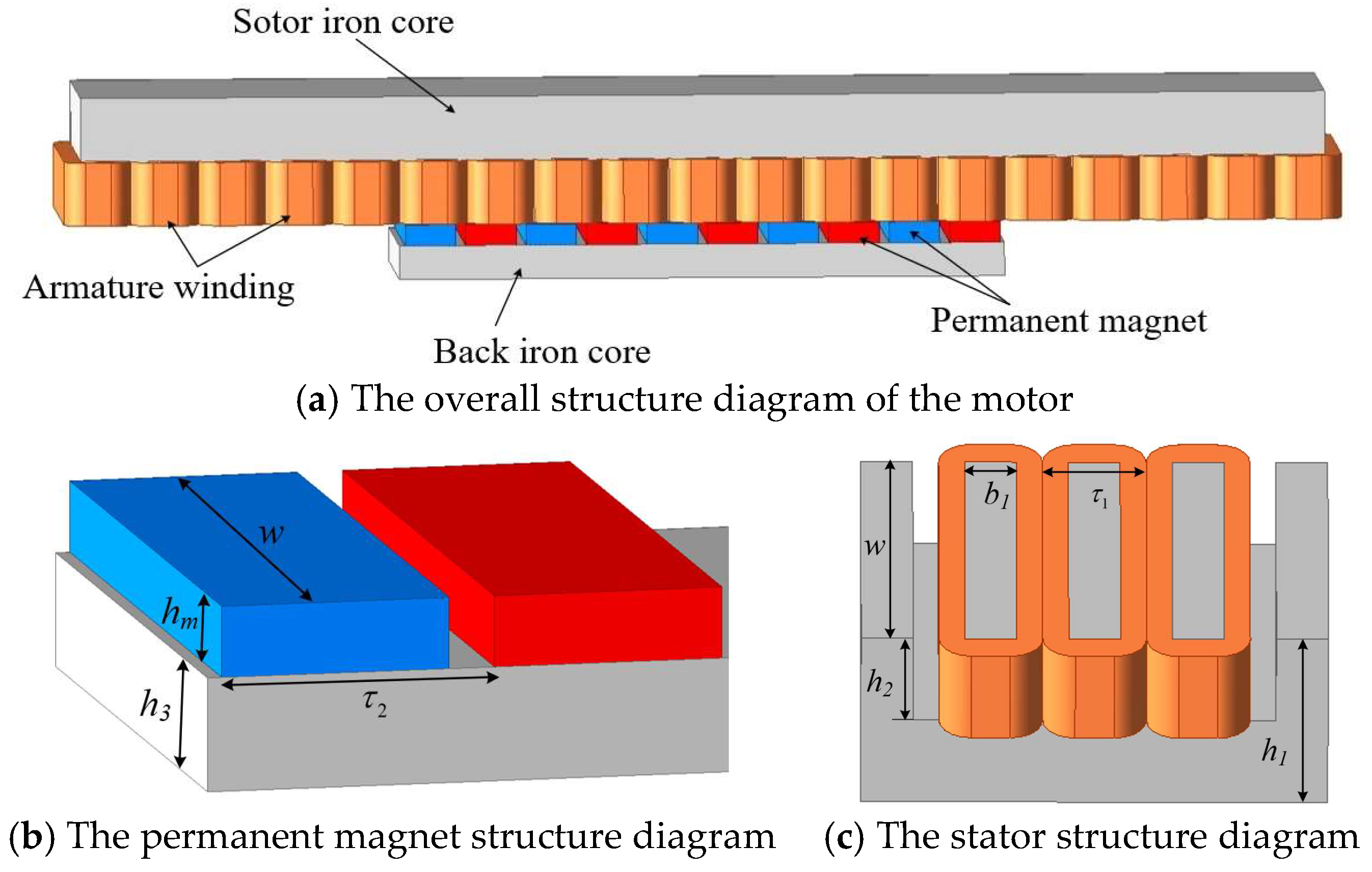

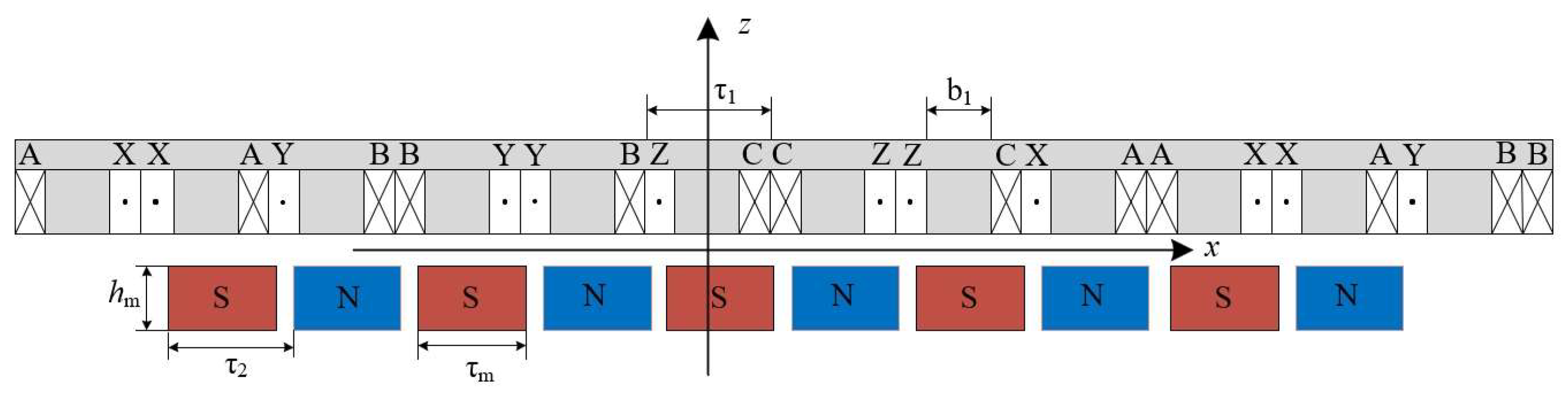

2. Structure and Operation Principle

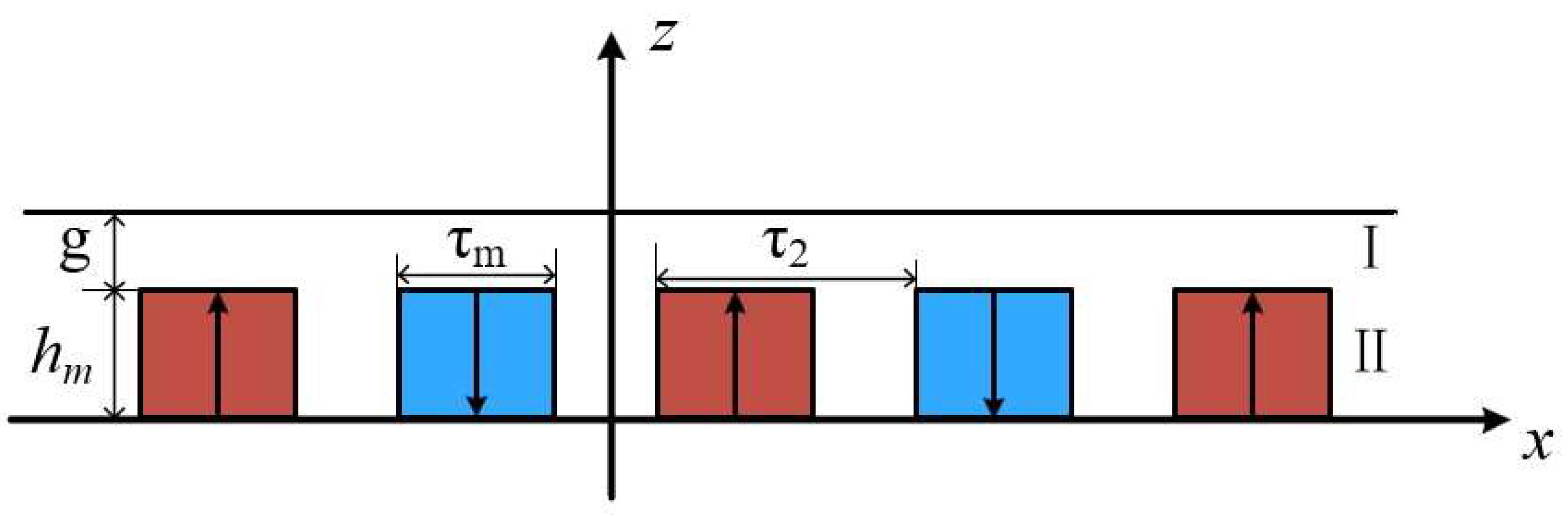

Modeling of the PMLSM

- (1)

- The stator and mover of the motor are infinitely long, and the models of each region extend infinitely along the x-axis;

- (2)

- The transverse end effect is not considered, and the variation in the magnetic field along the z-axis is ignored;

- (3)

- The magnetic permeability of the stator core and the mover yoke is infinite;

- (4)

- Neglecting the leakage flux of windings and permanent magnets, the permanent magnets are uniformly magnetized.

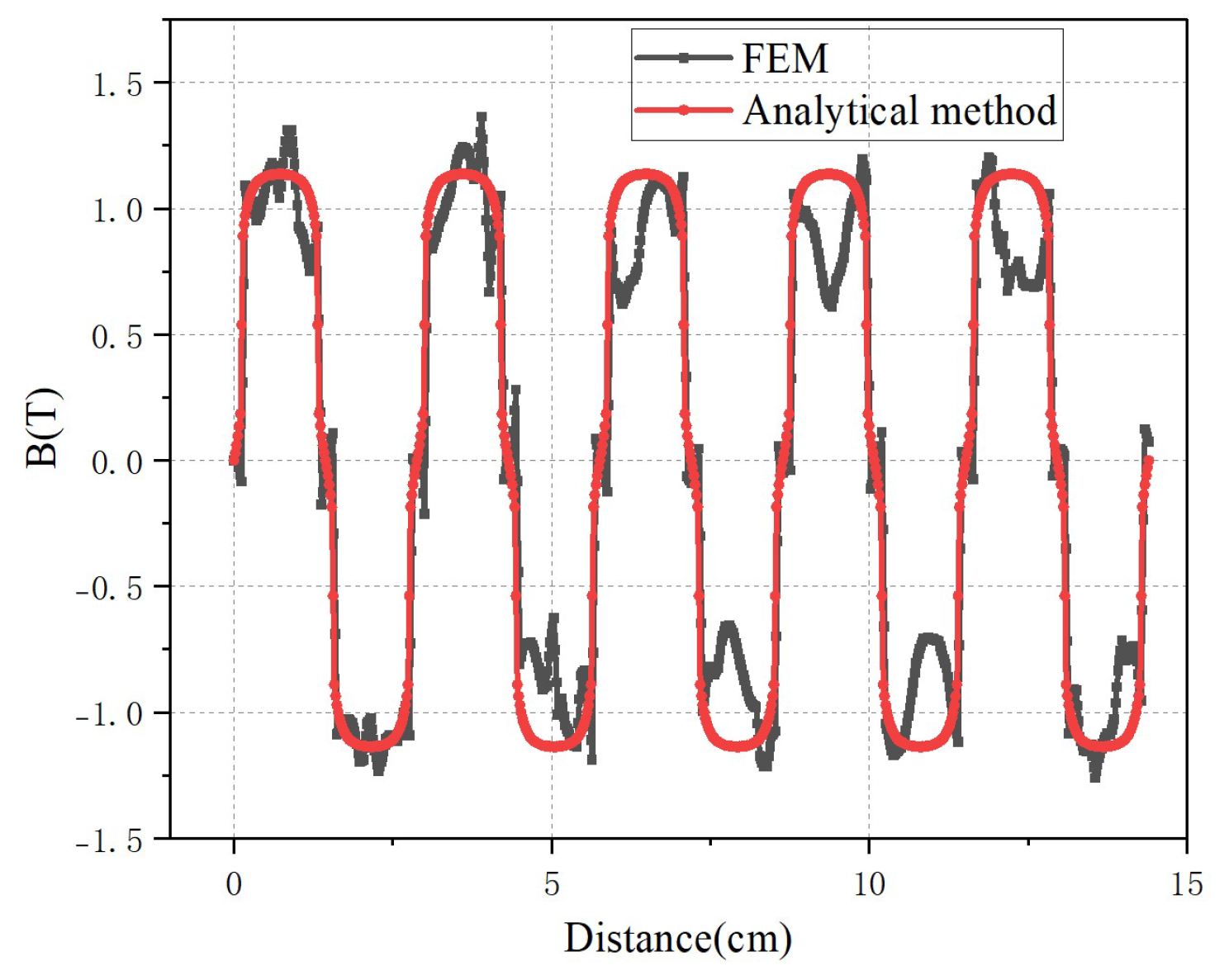

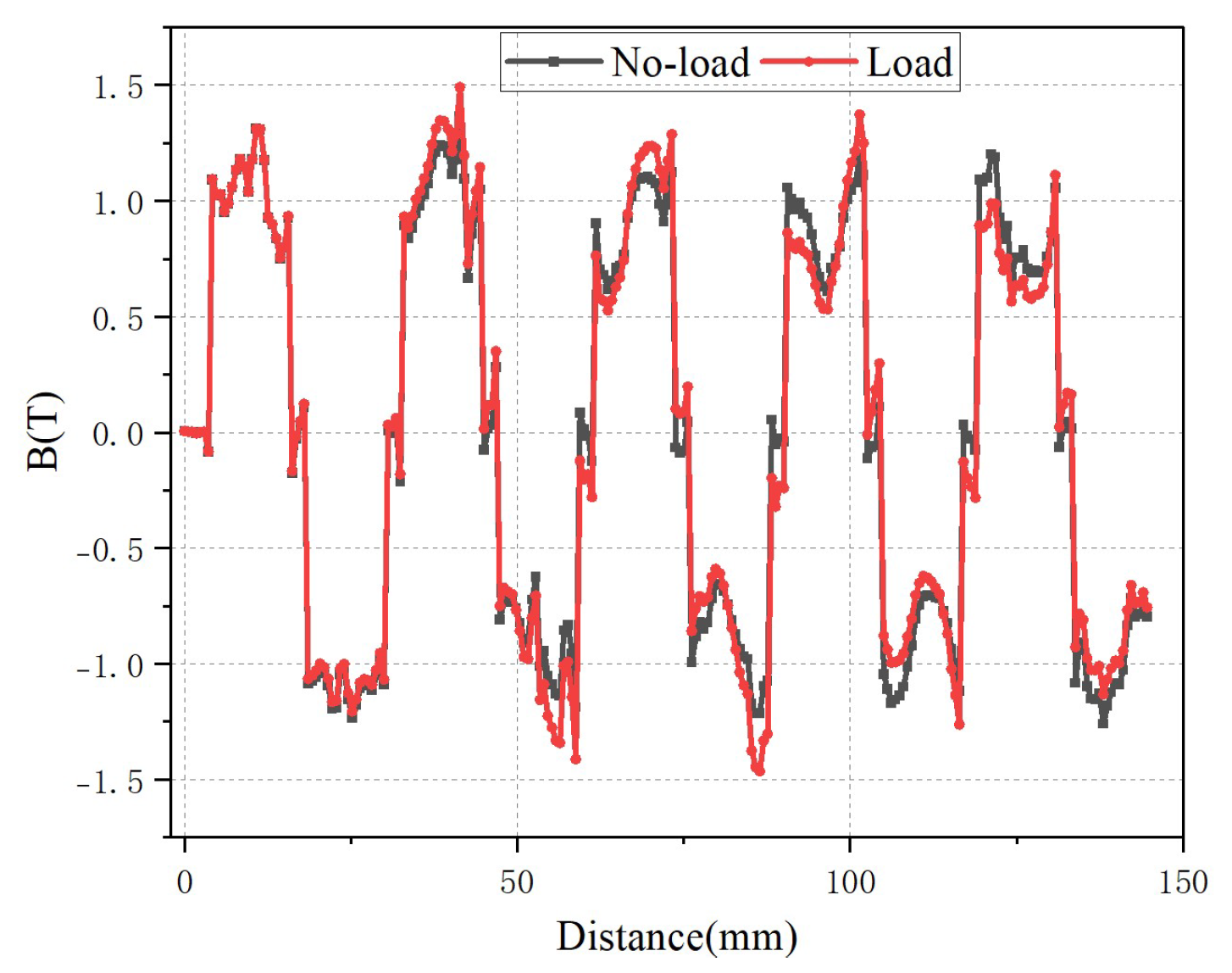

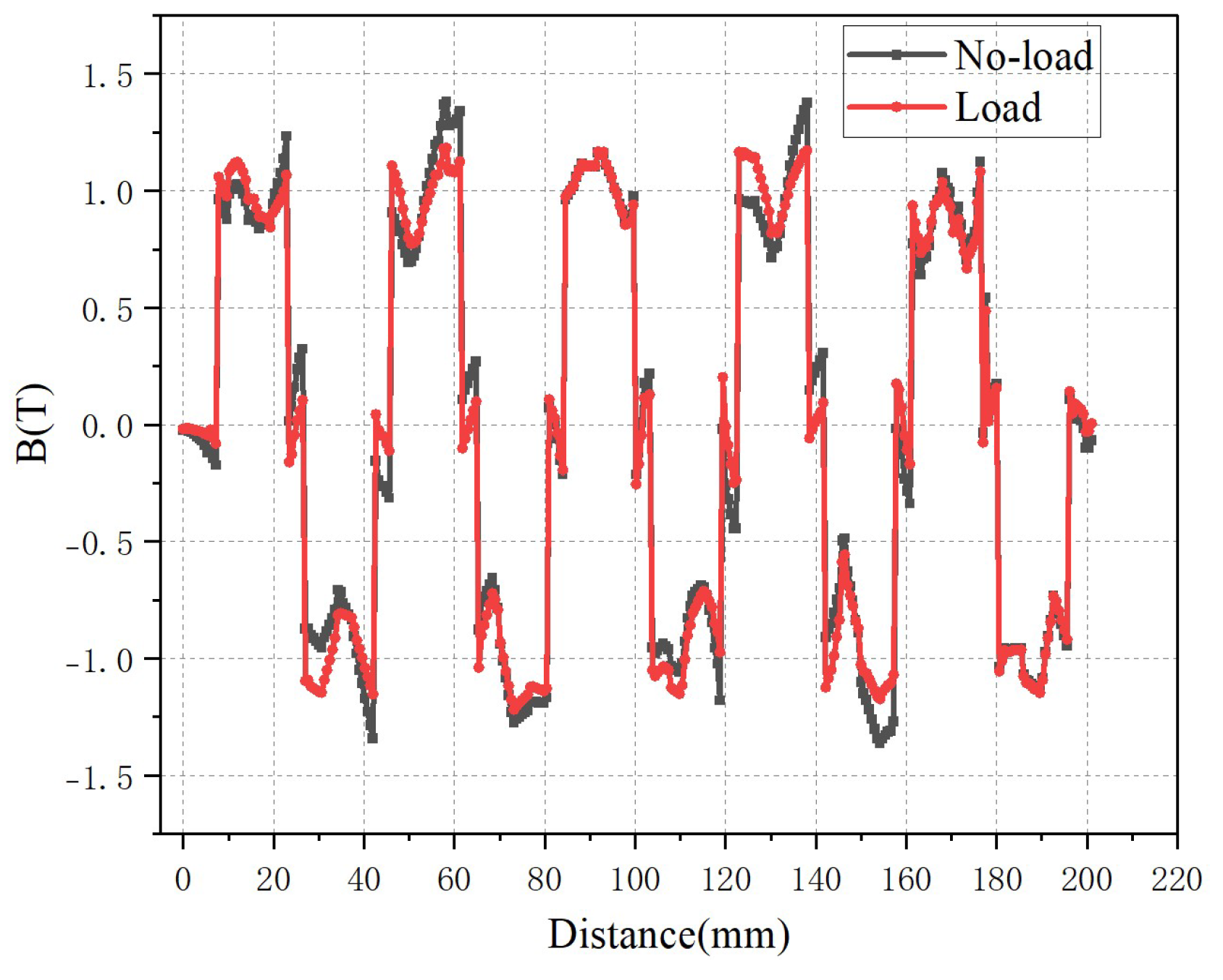

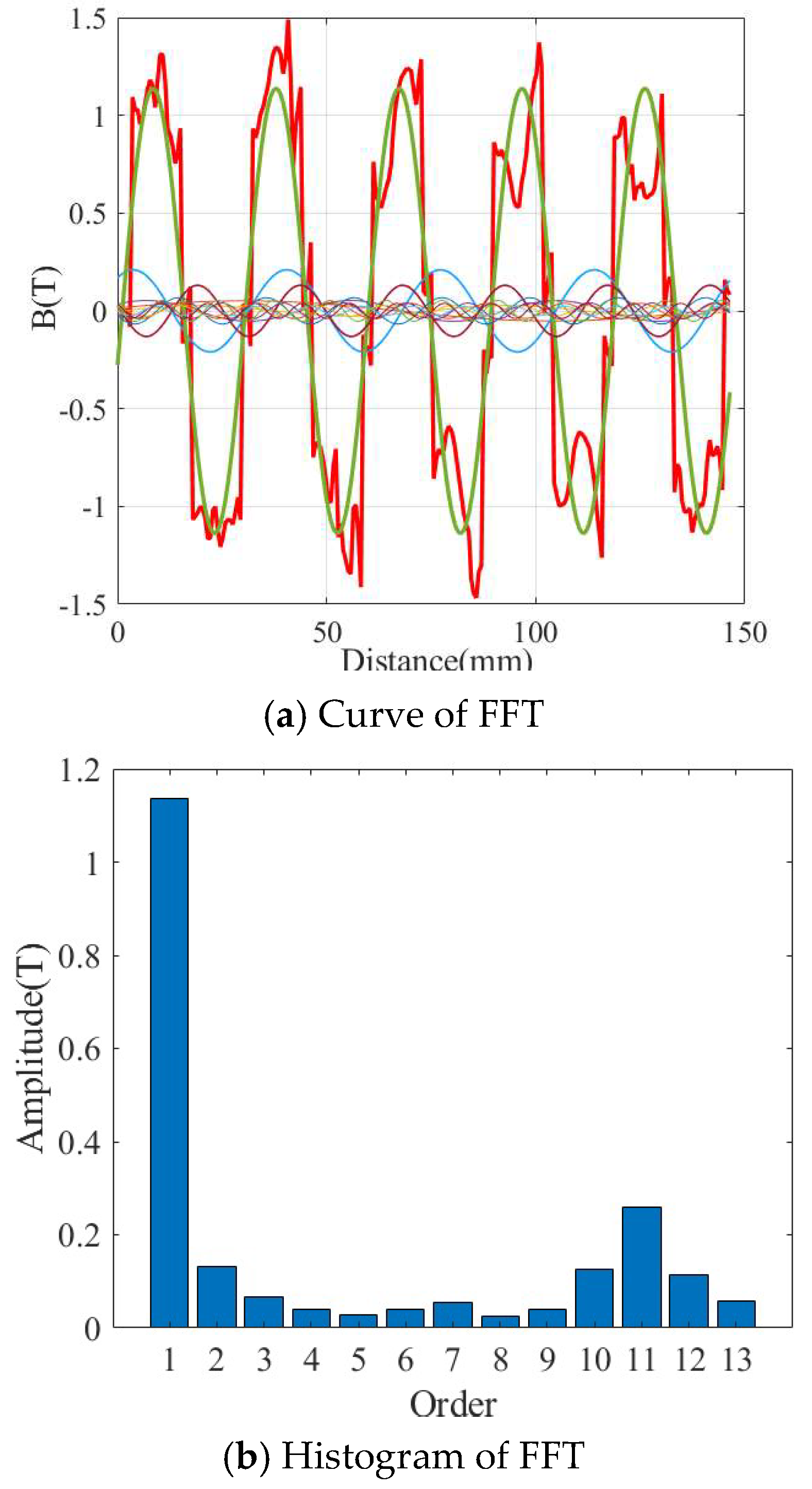

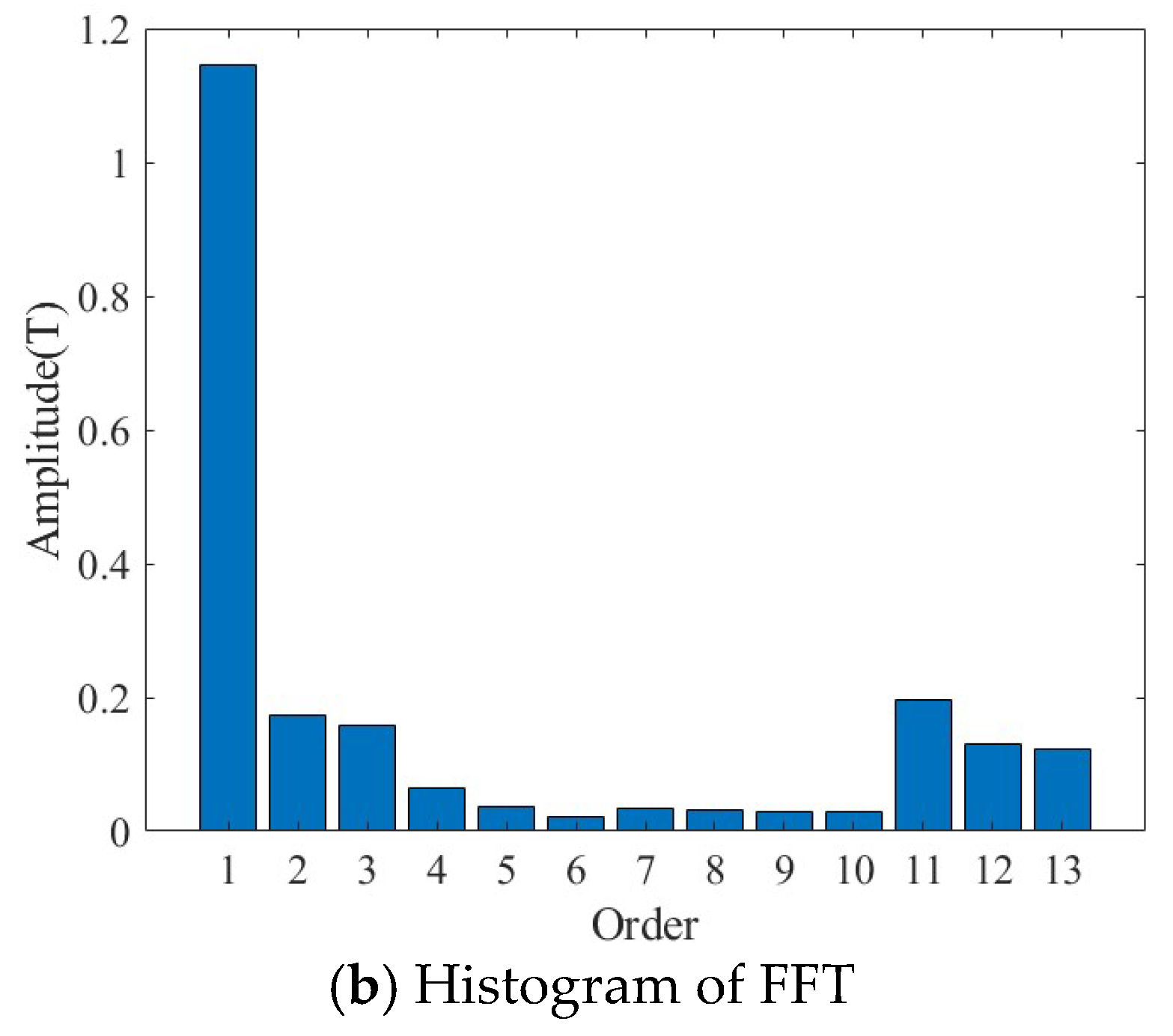

3. Model Verification and Result Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, X.Z.; Li, J.; Tan, Q.; Zhang, C.M.; Li, L. Design Principles of a Phase-Shift Modular Slotless Tubular Permanent Magnet Linear Synchronous Motor with Three Sectional Primaries and Analysis of Its Detent Force. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 65, 9346–9355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Liu, X.; Zhao, J.; Guo, Y. Analysis and Minimization of Detent End Force in Linear Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 65, 2475–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, B.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wen, T. Adaptive Backstepping Speed Control of Permanent Magnet Actuator Driven by Segmented Driving Coils in PMLSM. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2025, 13, 6624–6634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Huang, X.; Tian, B. Analysis and Suppression of Normal Force Ripple for Long Primary Permanent Magnet Linear Synchronous Motor. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2025, 61, 3674–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Li, L.; Huang, X. Improved Discrete-Time Resonant Extended State Observer Based Robust DPCC of Winding-Discontinuous-Segmented PMLSM. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 5716–5727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhao, X.R.; Wang, Q.W.; Tong, B.; Li, S.; Wang, G.; Xu, D. Adaptive Fourier ILC for Mover Position Estimation Error Suppression for Sensorless PMLSM Drives. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2025, 13, 1627–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Guo, J.; Dong, F. Cumulative Error Elimination for PMLSM Mover Displacement Measurement Based on BP Neural Network Model and SVD. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2025, 61, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Ding, A.; Mao, Y.; Huang, C.; Xu, W. Improved Adaptive Speed Observer of Permanent Magnet Linear Synchronous Motor With Transient Characteristics. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2025, 13, 2330–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong-Yeup, L.; Gyu-Tak, K. Design of thrust ripple minimization by equivalent magnetizing current considering slot effect. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2006, 42, 1367–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yang, H.; Lin, H. A Hybrid Field Analytical Method of Hybrid-Magnetic-Circuit Variable Flux Memory Machine Considering Magnet Hysteresis Nonlinearity. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2021, 7, 2763–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.G.; Sarlioglu, B. 3-D Performance Analysis and Multiobjective Optimization of Coreless-Type PM Linear Synchronous Motors. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 65, 1855–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Sun, Z.; Xu, W.; Zhou, W.; Liu, Y. Comparative analysis of bilateral permanent magnet linear synchronous motors with different structures. CES Trans. Electr. Mach. Syst. 2020, 4, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Jin, Y.; Lu, M.; Zhang, Z. Quantitative Comparison of Linear Flux-Switching Permanent Magnet Motor with Linear Induction Motor for Electromagnetic Launch System. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 65, 7569–7578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yücel, E.; Mutluer, M.; Cunkas, M. Analysis and design of a permanent magnet linear synchronous motor based on inductance calculation. Arch. Electr. Eng. 2025, 74, 773–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Luo, M.; Duan, J.A.; Kou, B. Design and Modeling of a Novel Permanent Magnet Width Modulation Secondary for Permanent Magnet Linear Synchronous Motor. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 2749–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isfahani, A.H. Analytical Framework for Thrust Enhancement in Permanent-Magnet (PM) Linear Synchronous Motors With Segmented PM Poles. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2010, 46, 1116–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh-Ghalavand, B.; Vaez-Zadeh, S.; Isfahani, A.H. An Improved Magnetic Equivalent Circuit Model for Iron-Core Linear Permanent-Magnet Synchronous Motors. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2010, 46, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.A.; Peng, J.X.; Hsieh, M.F.; Huang, P.W. Anti-Demagnetization Analysis of Fractional Slot Concentrated Windings Interior Permanent Magnet Motor Considering Effect of Rotor Design Parameters. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2022, 58, 8201606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Shang, F.; Brown, I.P.; Krishnamurthy, M. Comparative Study of Interior Permanent Magnet, Induction, and Switched Reluctance Motor Drives for EV and HEV Applications. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2015, 1, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Dong, F.; Zhao, J.; Lu, S.; Dou, S.; Wang, H. Optimal design of permanent magnet linear synchronous motors based on Taguchi method. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2017, 19, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knypiński, Ł.; Reddy, A.V.; Venkateswararao, B.; Devarapalli, R. Optimal design of brushless DC motor for electromobility propulsion applications using Taguchi method. J. Electr. Eng. 2023, 74, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Quantity | Value |

|---|---|---|

| τ | Pole pitch of 9-slot/12-slot | 14.4/19.2 mm |

| g | Air-gap | 0.5 mm |

| I1 | Stator phase current | 100 A |

| N1 | Stator phase current turns | 50 |

| hm | Permanent magnet height | 5 mm |

| τ1 | Stator slot pitch | 12mm |

| τ2 | Pole length | 16 mm |

| b1 | Stator tooth width | 8 mm |

| w | Permanent magnet width | 50 mm |

| h1 | Stator iron height | 30 mm |

| h2 | Iron tooth height | 15 mm |

| h3 | Permanent magnet backplate height | 8 mm |

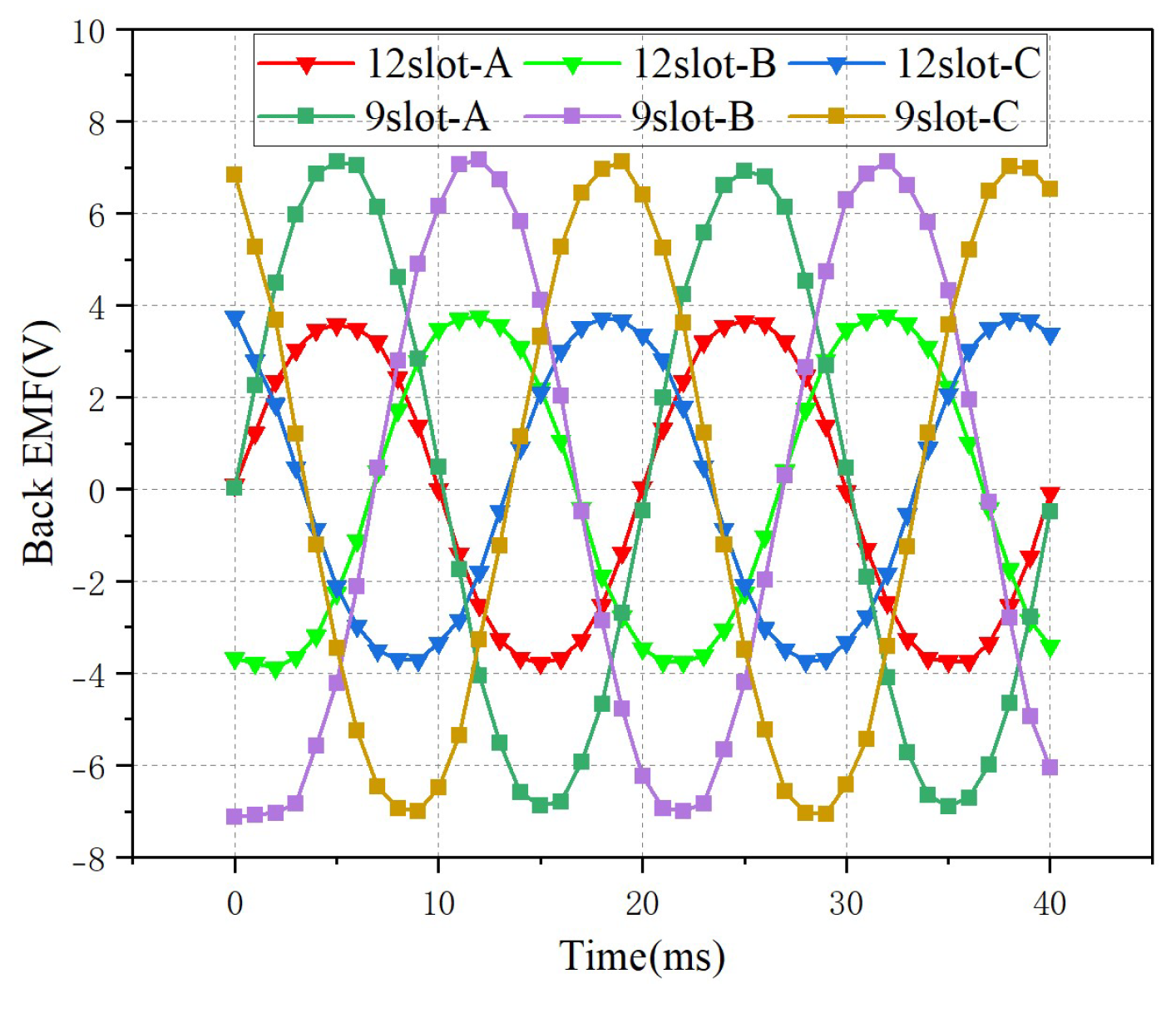

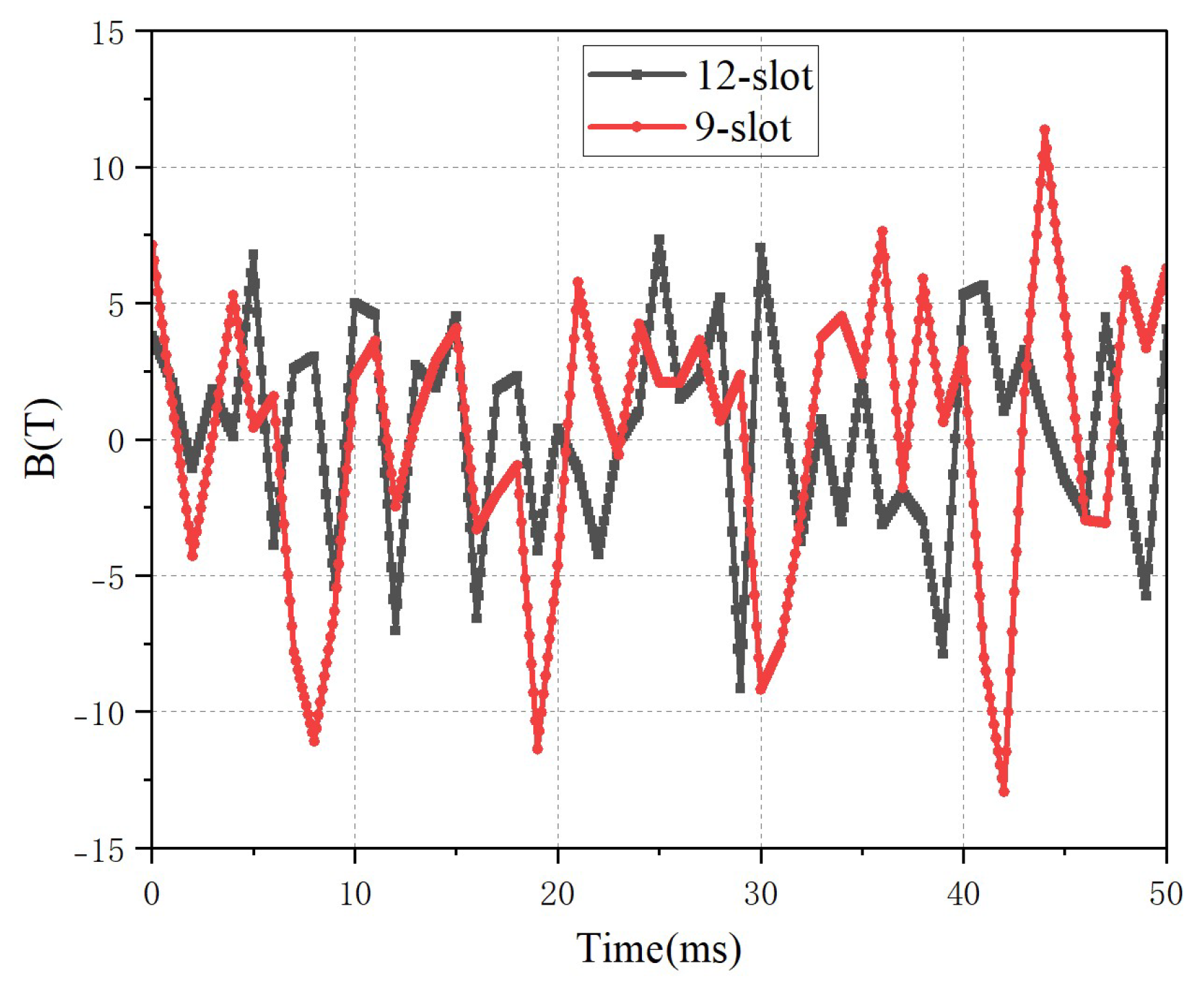

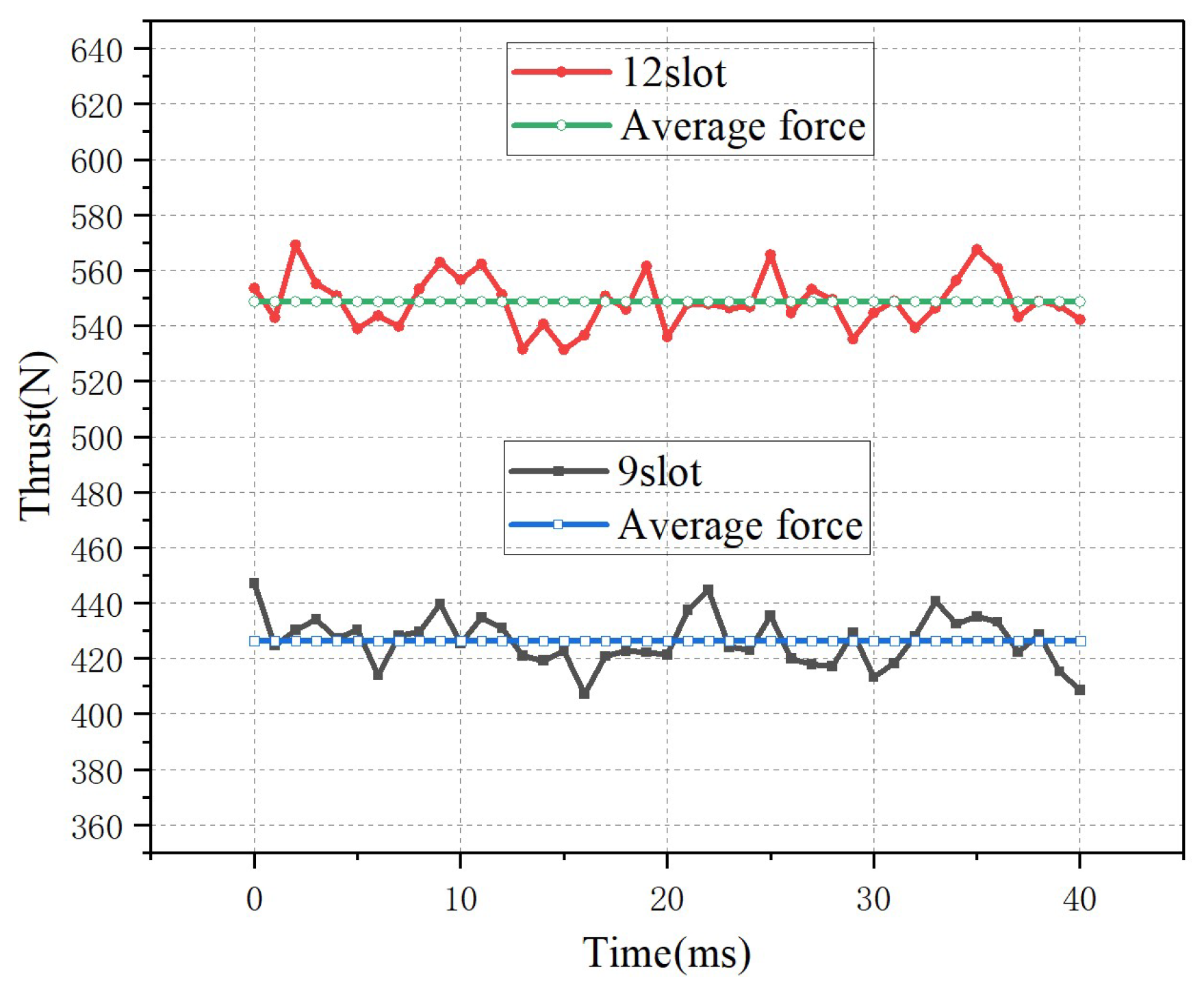

| Performance Metric | 9-slot/10-pole | 12-slot/10-pole | Analysis and Discussion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air-gap Flux Density Fundamental (T) | 1.3 T | 1.12 T | The 9-slot structure has a higher flux density, which is beneficial for improving thrust density. |

| 11th Harmonic (T) | 0.3 T | 0.19 T | The 12-slot structure is superior in suppressing specific harmonics. |

| Cogging Force (N) | 12.5 N | 9 N | The 12-slot structure has a smaller cogging force, which is conducive to stable operation. |

| Average Thrust (N) | 425 N | 549 N | The 12-slot structure provides greater average thrust. |

| Thrust Ripple Rate | 4.7% | 3.6% | The 12-slot structure achieves more stable thrust. |

| Back-EMF (V) | 4 V | 7 V | The 12-slot structure has a higher back-EMF. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bai, J.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Y. Analysis on the Air-Gap Magnetic Field and Force of the Linear Synchronous Motor with Different Winding Distribution. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1396. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121396

Bai J, Zhang L, Xu Y. Analysis on the Air-Gap Magnetic Field and Force of the Linear Synchronous Motor with Different Winding Distribution. Micromachines. 2025; 16(12):1396. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121396

Chicago/Turabian StyleBai, Jing, Lei Zhang, and Yu Xu. 2025. "Analysis on the Air-Gap Magnetic Field and Force of the Linear Synchronous Motor with Different Winding Distribution" Micromachines 16, no. 12: 1396. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121396

APA StyleBai, J., Zhang, L., & Xu, Y. (2025). Analysis on the Air-Gap Magnetic Field and Force of the Linear Synchronous Motor with Different Winding Distribution. Micromachines, 16(12), 1396. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121396