Muscle Strength Training and Monitoring Device Based on Triboelectric Nanogenerator for Knee Joint Surgery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Production of MSTKJS-TENG

2.2. Experimental Equipment

3. Results and Discussion

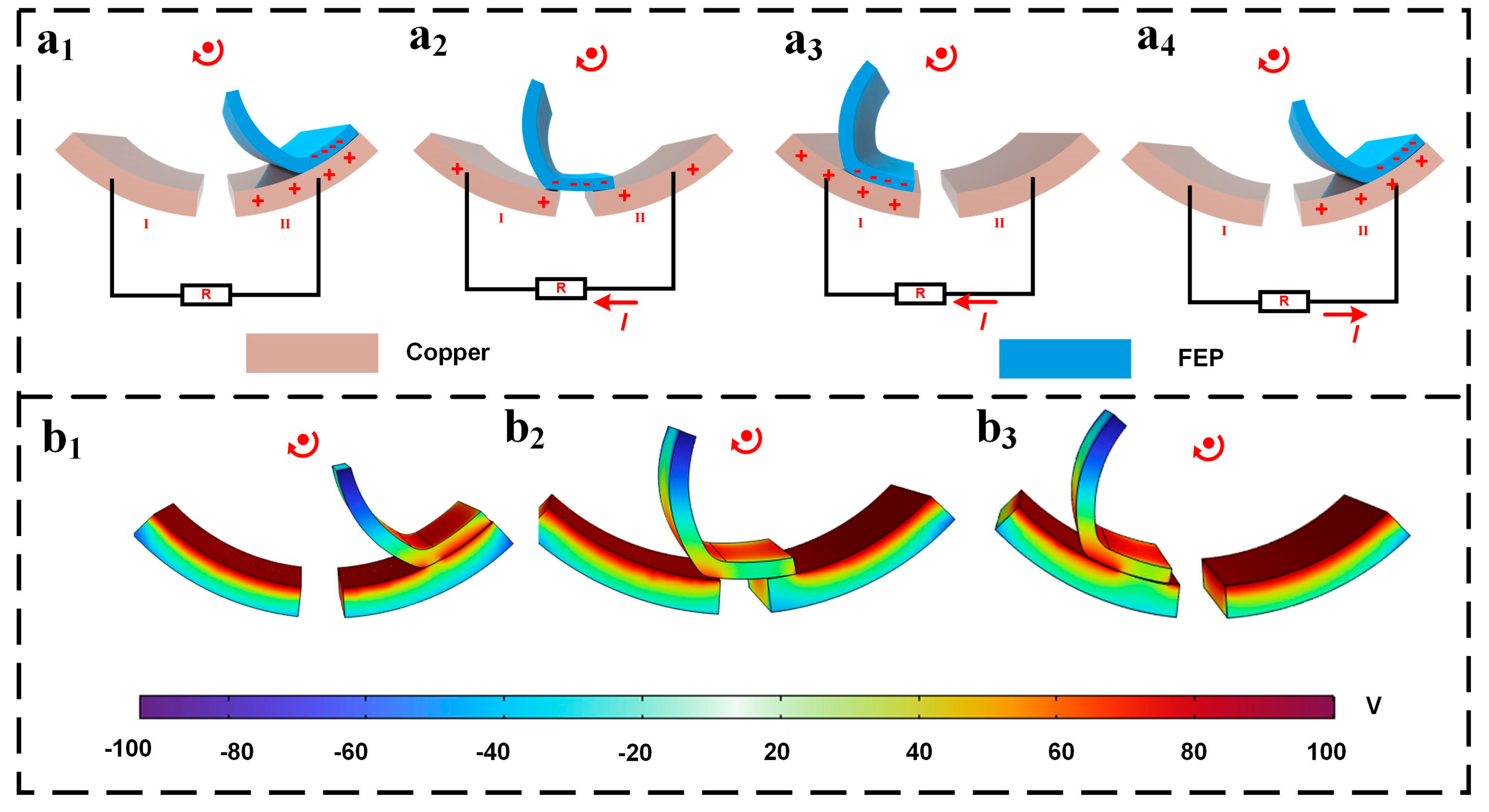

3.1. Structural Design and Working Principle

3.2. Power Generation Performance Test

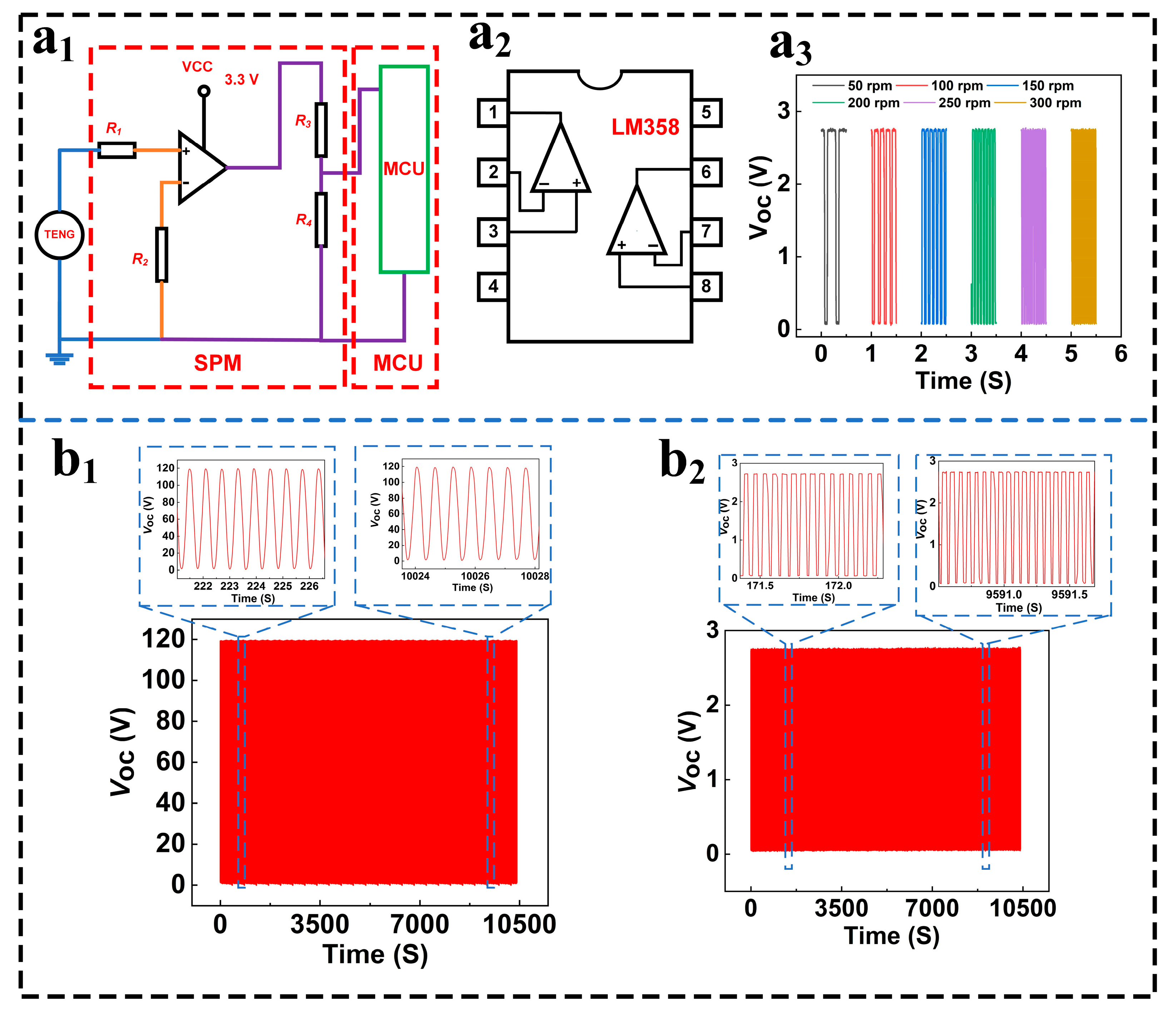

3.3. Microprogrammed Control Unit Performance Test

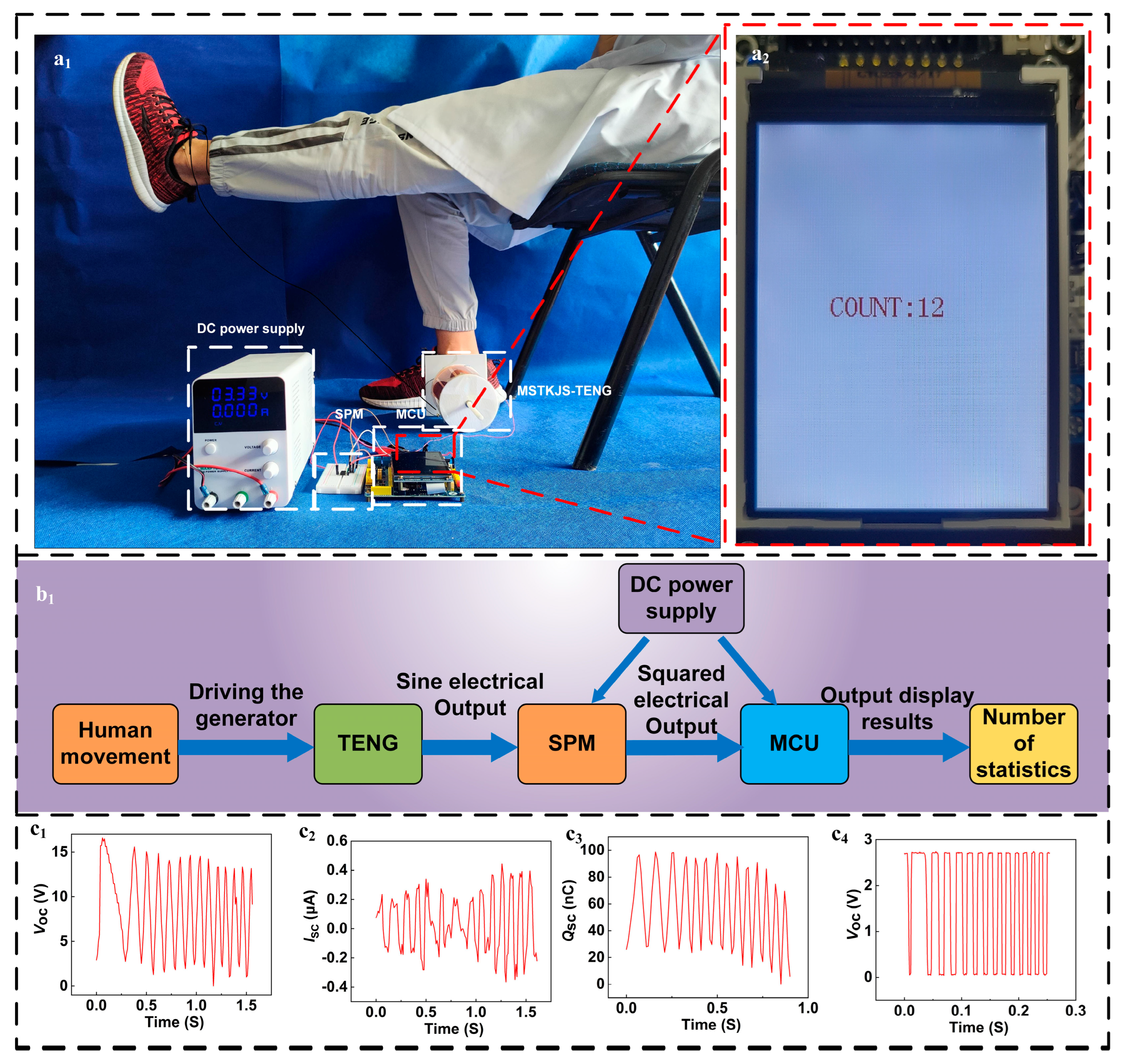

3.4. Demonstration

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Du, X.; Liu, Z.; Tao, X.; Mei, Y.; Zhou, D.; Cheng, K.; Gao, S.; Shi, H.; Song, C.; Zhang, X. Research progress on the pathogenesis of knee osteoarthritis. Orthop. Surg. 2023, 15, 2213–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Xia, R.; Zhu, C.; Wu, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Ma, J. Effect of Femoral Nerve Block with Different Concentrations of Chloroprocaine on Early Postoperative Rehabilitation Training After Total Knee Arthroplasty. Med. Sci. Monit. 2023, 29, e939858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco, J.; Igual-Camacho, C.; Blasco, M. The efficacy of virtual reality tools for total knee replace-ment rehabilitation: A systematic review. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2021, 37, 682–692. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, J.; Qing, L.; Wang, H.; Ma, H.; Huang, P. Effect of quadriceps training at different levels of blood flow restriction on quadriceps strength and thickness in the mid-term postoperative period after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A randomized controlled external pilot study. BMC Musculoskel. Disord. 2023, 24, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singla, R.; Niederer, D.; Franz, A.; Happ, K.; Zilkens, C.; Wahl, P.; Behringer, M. The course of knee extensor strength after total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review with meta-analysis and -regression. Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 2023, 143, 5303–5322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, T.; Bell, L.; Bender, A.; Trepczynski, A.; Duda, G.N.; Baur, A.J.D.; Damm, P. Periarticular muscle status affects in vivo tibio-femoral joint loads after total knee arthroplasty. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1075357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.J.; Forrest, G.; Cortes, M.; Weightman, M.M.; Sadowsky, C.; Chang, S.-H.; Furman, K.; Bialek, A.; Prokup, S.; Carlow, J.; et al. Walking improvement in chronic incomplete spinal Co-rd injury with exoskeleton robotic training (WISE): A randomized controlled trial. Spinal. Cord 2022, 60, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A.; Shandhi, M.H.; Master, H.; Dunn, J.; Brittain, E. Wearable devices in cardiovascular medicine. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, 652–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Gonzalez, M.; Sanchez-Ballester, J.; Suchomel, T. Drawbacks of existing muscle strength training devices: A comprehensive review. J. Sport. Sci. 2019, 37, 477–489. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, W.J.; Sipahi, R.; Sanger, T.D.; Sternad, D. Portable Motion-Analysis Device for Upper-Limb Research, Assessment, and Rehabilitation in Non-Laboratory Settings. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 2019, 7, 2800314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.L. Triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG)-sparking an energy and sensor revolution. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 2000137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Jiang, T.; Wang, Z. Theoretical Foundations of Triboelectric Nanogenerators (TENGs). Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2020, 63, 1087–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wang, A.C.; Ding, W.; Guo, H.; Wang, Z.L. Triboelectric nanogenerator: A foundation of the energy for the new. Era. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1802906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; Chen, J.; Lin, L. Progress in triboelectric nanogenerators as a new energy technology and self-powered sensors. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 2250–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L. Triboelectric Nanogenerators as new energy technology for self-powered systems and as active mechanical and chemical sensors. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 9533–9557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Jin, T.; Cai, J.; Xu, L.; He, T.Y.Y.; Wang, T.H.; Tian, Y.Z.; Li, L.; Peng, Y.; Lee, C.K. Wearable triboelectric sensors enabled gait analysis and waist motion capture for iot-based smart healthcare applications. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, e2103694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aamir Jan, A.; Kim, S.; Kim, S. A micro-dome array triboelectric nanogenerator with a nanocomposite dielectric enhancement layer for wearable pressure sensing and gait analysis. Soft Matter 2024, 20, 6558–6567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, J.; Cho, H.; Park, J.; Kim, D. Self-powered and flexible triboelectric sensors with oblique morphology towards smart swallowing rehabilitation monitoring system. Materials 2022, 15, 2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; He, T.; Zhang, Z.; Ao, H.; Jiang, H.; Lee, C. A motion capturing and energy harvesting hybridized lower-limb system for rehabilitation and sports applications. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, e2101834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Zheng, Q.; Shi, Y.; Xu, L.; Zou, Y.; Jiang, D.; Shi, B.; Qu, X.; Li, H.; Ouyang, H.; et al. Flexible and stretchable dual mode nanogenerator for rehabilitation monitoring and information interaction. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 3647–3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, H.; He, T.; He, B.; Thakor, N.V.; Lee, C. Investigation of low-current direct stimulation for rehabilitation treatment related to muscle function loss using self-powered TENG system. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1900149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Liu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Han, L.; Zhao, J. Research on the electronic switch of power management circuits for triboelectric nanogenerator. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2370, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Fu, X.; Zhu, H.; Qu, Z.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, G.; Zhang, C.; Ding, J. Self-powered non-contact motion vector sensor for multifunctional human-machine interface. Small Methods 2022, 6, 2200588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, D.; Lee, K.S.; Niazi, M.U.K.; Park, H.-S. Triboelectric nanogenerator integrated origami gravity support device for shoulder rehabilitation using exercise gaming. Nano Energy 2022, 97, 107179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Pu, X.; Zhou, S.; Wu, Y.; Li, G.; Xing, P.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, C. Deep learning enabled neck motion detection using a triboelectric nanogenerator. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 9359–9367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, D.; Xu, C.; Wang, Z.; Shu, S.; Sun, Z.; Tang, W.; Wang, Z.L. Sensing of joint and spinal bending or stretching via a retractable and wearable badge reel. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmieri-Smith, R.M.; Brown, S.R.; Wojtys, E.M.; Krishnan, C. Functional resistance training improves thigh muscle strength after ACL reconstruction: A randomized clinical trial. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2022, 54, 1729–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, D.; Kim, D.; Park, H.S. Smart exercise device using triboelectric self-powered sensor for high intensity interval training (HIIT). Biosens. Bioelectron. 2025, 290, 117995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procházka, R.; Stehlík, A.; Kotous, J.; Salvetr, P.; Bucki, T.; Stránský, O.; Zulić, S. Fatigue properties of spring steels after advanced processing. Materials 2023, 16, 3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Sun, C.; Wang, Y. Muscle Strength Training and Monitoring Device Based on Triboelectric Nanogenerator for Knee Joint Surgery. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1387. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121387

Liu J, Zhang Y, Liu X, Sun C, Wang Y. Muscle Strength Training and Monitoring Device Based on Triboelectric Nanogenerator for Knee Joint Surgery. Micromachines. 2025; 16(12):1387. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121387

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jing, Yi Zhang, Xia Liu, Chenming Sun, and Youquan Wang. 2025. "Muscle Strength Training and Monitoring Device Based on Triboelectric Nanogenerator for Knee Joint Surgery" Micromachines 16, no. 12: 1387. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121387

APA StyleLiu, J., Zhang, Y., Liu, X., Sun, C., & Wang, Y. (2025). Muscle Strength Training and Monitoring Device Based on Triboelectric Nanogenerator for Knee Joint Surgery. Micromachines, 16(12), 1387. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi16121387